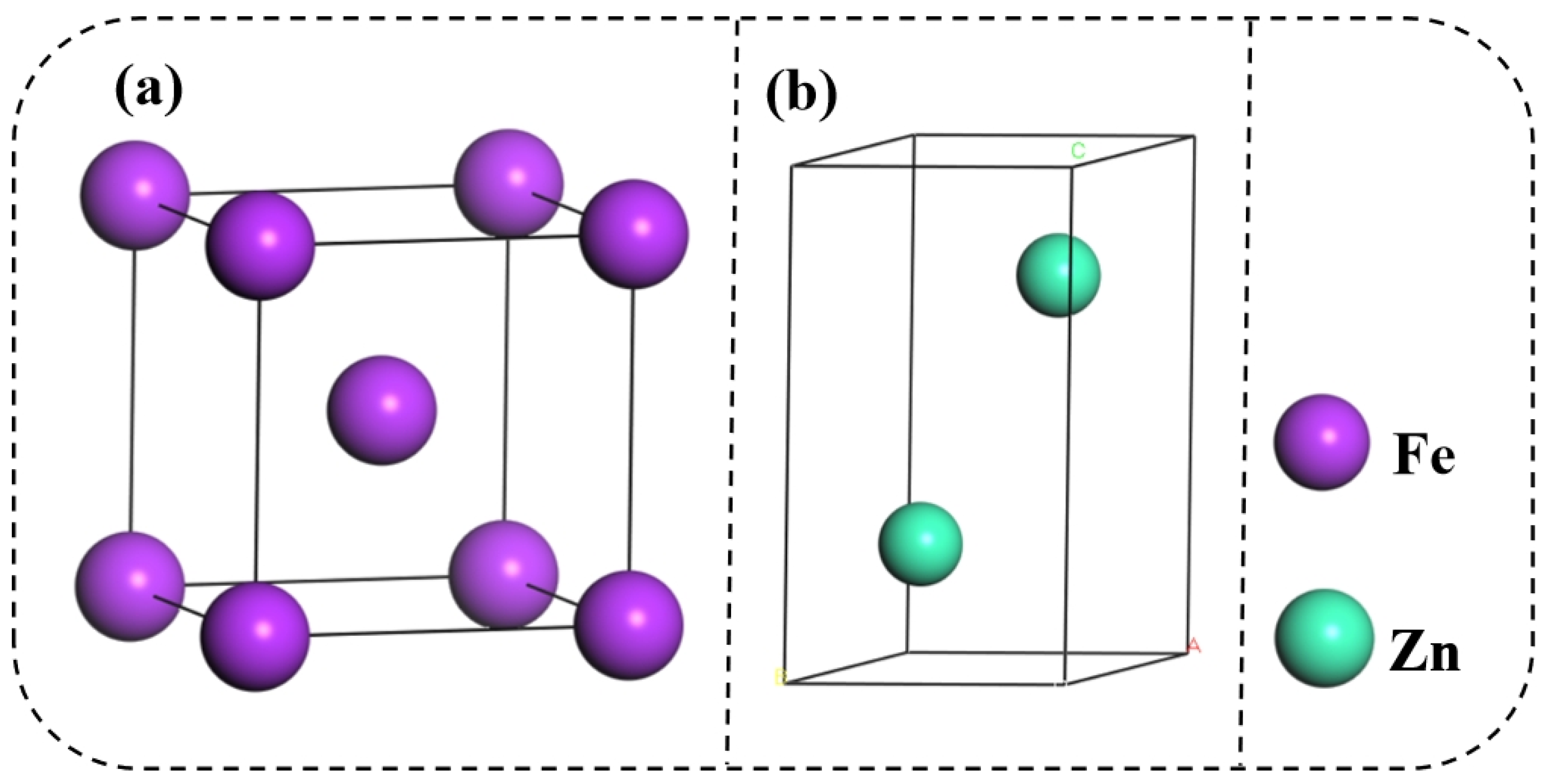

3.1. Surface Model

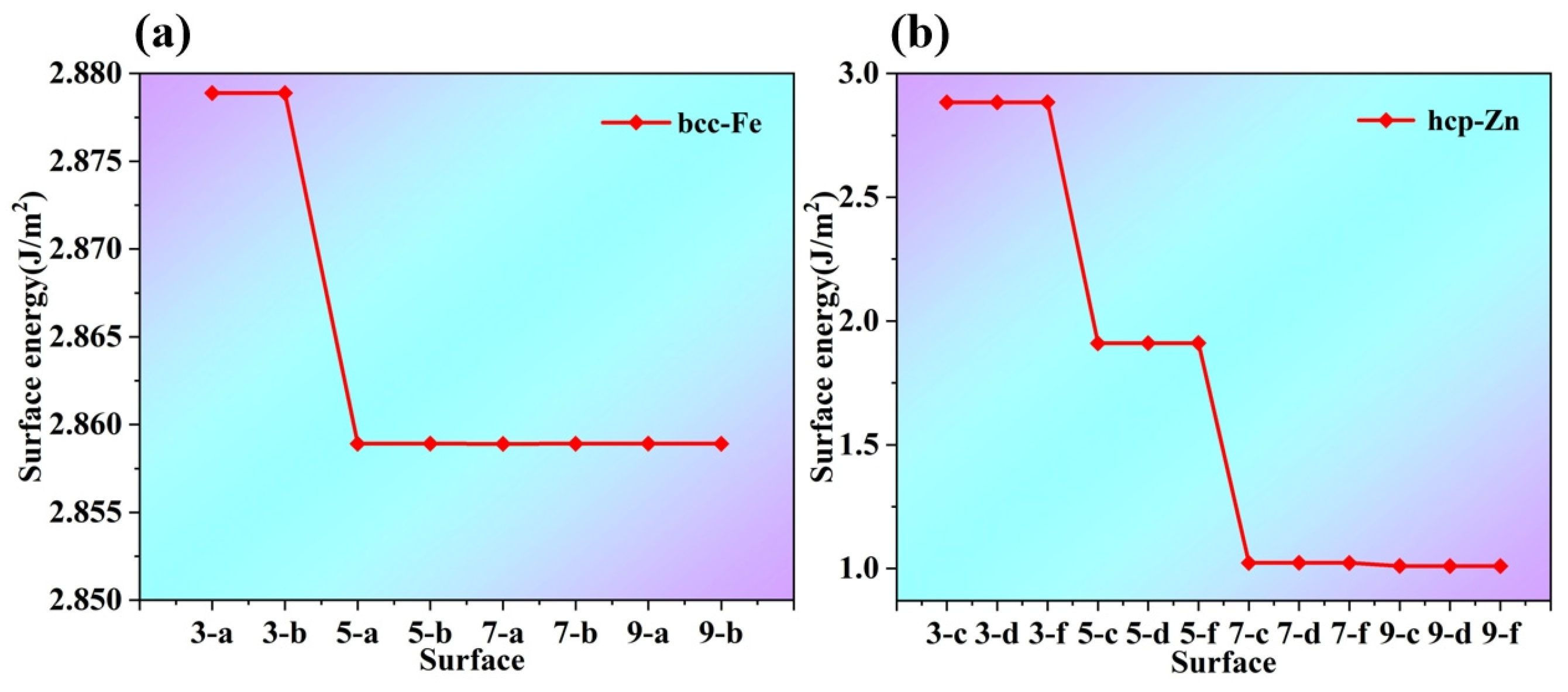

First, the surface models of the bcc-Fe(110) plane and hcp-Zn(101) plane were constructed, respectively. When the bcc-Fe is cut along the (110) surface, there are two different terminations, namely a and b; when the hcp-Zn is cut along the (101) surface, there are three different terminations, namely c, d, and f. To ensure that atoms deep in the surface possess the characteristics of bulk-phase atoms, a sufficiently thick number of atomic layers is required. Therefore, for both bcc-Fe and hcp-Zn, surface construction was carried out with 3, 5, 7, and 9 atomic layers, respectively. Based on the different layer numbers and terminations, 8 surface models were built for bcc-Fe, which are 3-a, 3-b, 5-a, 5-b, 7-a, 7-b, 9-a, and 9-b; and 12 surface models were constructed for hcp-Zn, namely 3-c, 3-d, 3-f, 5-c, 5-d, 5-f, 7-c, 7-d, 7-f, 9-c, 9-d, and 9-f. Considering the limitation of interface matching degree, the supercell method with periodic boundary conditions was adopted in the surface construction process. A 15 Å vacuum layer was added to the surface models to prevent charge interactions between the atoms of the models.

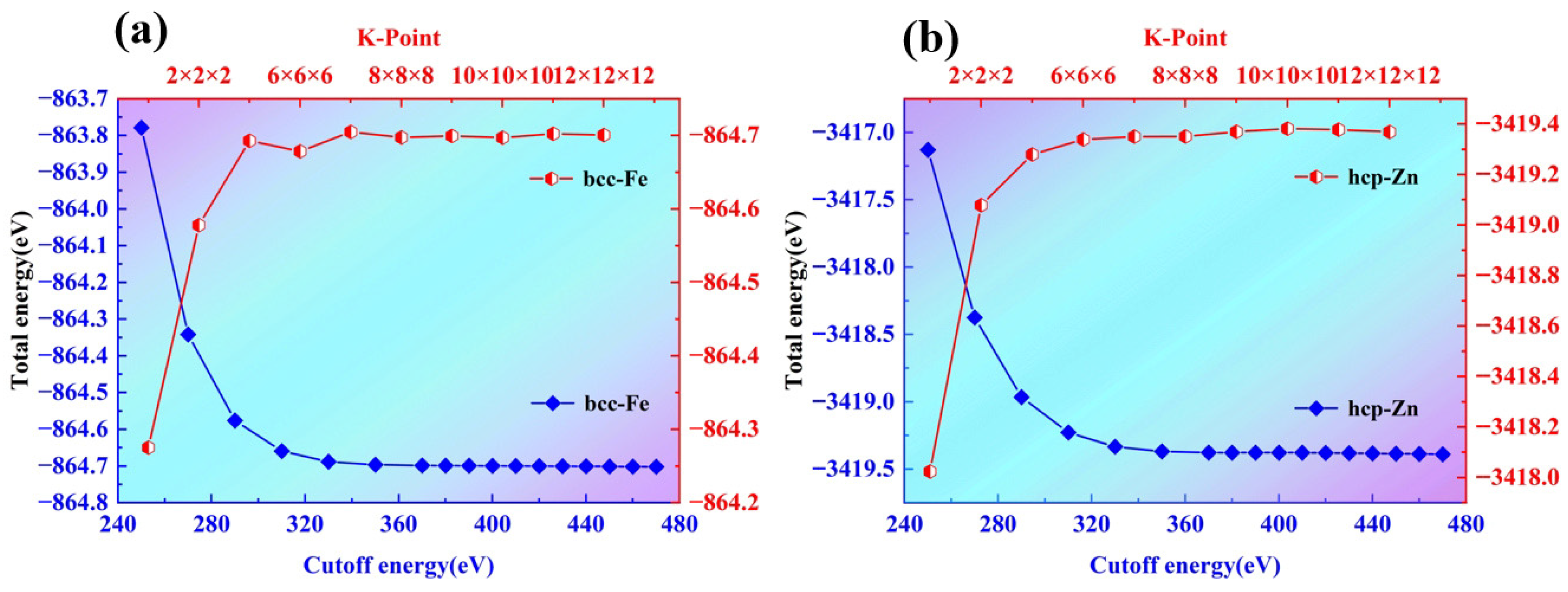

As the number of atomic layers gradually increases, the required computing power will increase significantly. Therefore, it is necessary to determine the optimal number of atomic layers by conducting surface energy tests on different numbers of atomic layers. The surface energy of a solid-phase crystal refers to the energy required to split the crystal in half along a crystal plane to form a new surface [

23], which can be used to judge the stability of the surface. Thus, in this study, surface energy convergence tests will be conducted to determine the number of atomic layers. By calculating the surface energy of different layer numbers and observing their convergence trends, the optimal number of atomic layers for the surface model will be finally determined. The surface energies of bcc-Fe and hcp-Zn can be transformed and calculated using the following formula [

24,

25]:

where

Eslab(

n) denotes the total energy of the Fe surface slab model,

n is the number of Fe atoms in the surface slab model, ∆

E represents the energy increment determined by

, and

A is the area of the surface slab model. By converting the energy difference between surface models into that between the surface model and the bulk, the following applicable formula is obtained:

Which, Eslab represents the energy of the surface slab, Ebulk represents the total energy of the bulk, N denotes the ratio of the number of atoms in the surface slab to that in the bulk, and A stands for the area of the surface slab.

As shown in

Figure 4a,b, the Surface Energy Analysis of bcc-Fe, at the surface corresponding to the abscissa “3-a”, the surface energy of bcc-Fe is at a relatively high level, approximately 2.880 J/m

2. This indicates that under this specific surface condition, the surface has high energy due to factors such as the high degree of coordination unsaturation of surface atoms and the presence of numerous dangling bonds. As the abscissa transitions from “3-a” to “3-b”, the surface energy decreases sharply, and near “5-a”, it drops to a range of approximately 2.855 J/m

2 to 2.860 J/m

2. After that, the change in surface energy tends to be gentle. This suggests that with further changes in the surface state, the coordination of surface atoms is gradually improved, the impact of newly added surface state changes on surface energy is gradually reduced, and the surface energy gradually approaches a relatively stable value.

Surface Energy Analysis of hcp-Zn: At the surface corresponding to the abscissa “3-d”, the surface energy of hcp-Zn is approximately 2.9 J/m2, which is higher than the initial surface energy of bcc-Fe. This may be related to the crystal structure of hcp-Zn and the atomic arrangement of this surface, resulting in a higher degree of instability of surface atoms and thus higher surface energy. Starting from “3-d”, the surface energy decreases significantly: near “5-f”, it drops to approximately 2.0 J/m2, and then continues to decrease, approaching 1.0 J/m2 at the end of the abscissa. This indicates that the surface energy of hcp-Zn is more sensitive to changes in the surface state; as the surface state changes, the coordination environment of surface atoms is greatly improved, thereby significantly reducing the surface energy.

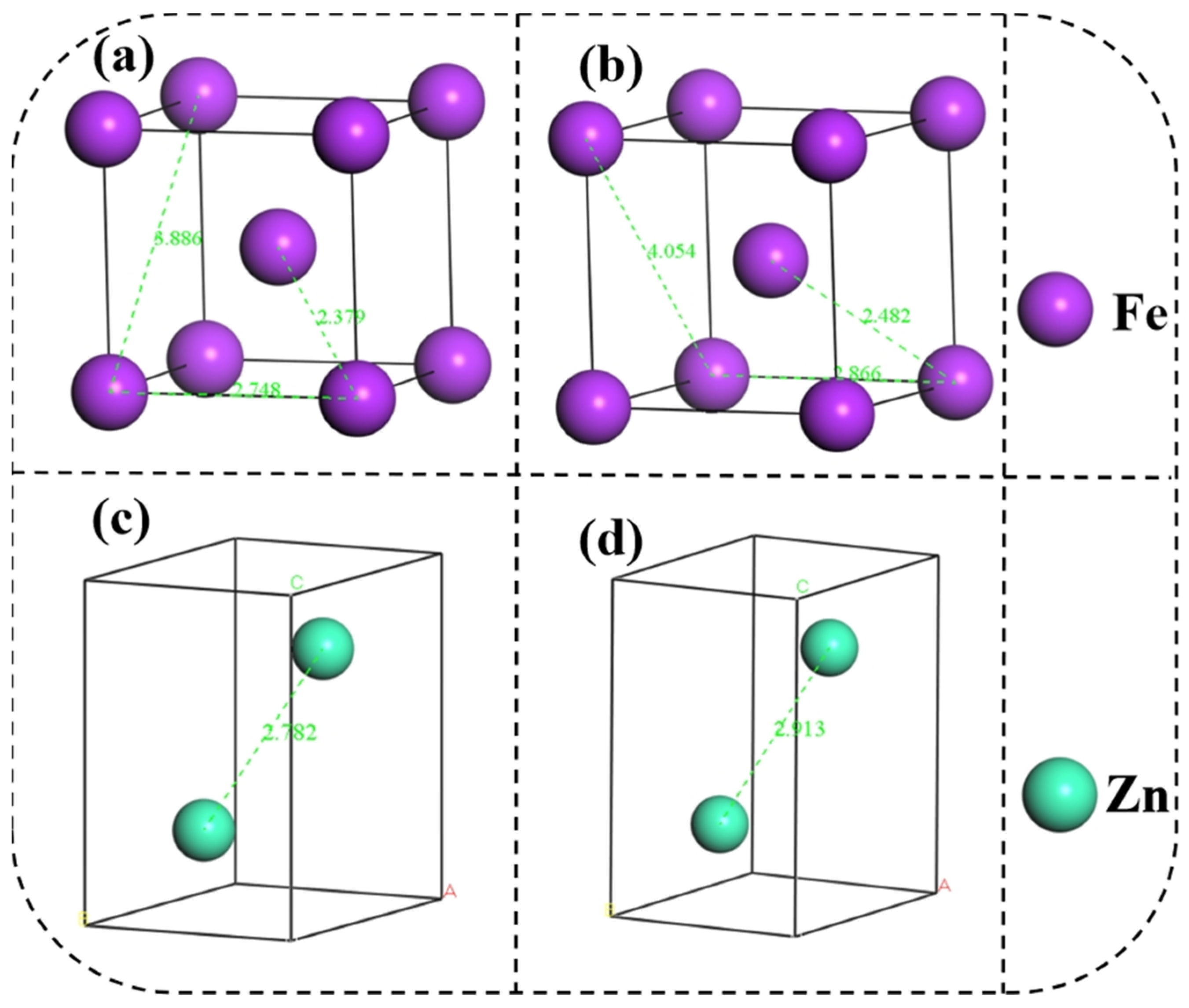

The surface energies of bcc-Fe (body-centered cubic iron) and hcp-Zn (hexagonal close-packed zinc) both change with variations in surface layer number and termination. Due to the differences in their crystal structures (bcc vs. hcp), there are significant disparities in the numerical values of their surface energies and their variation patterns. The crystal structure, surface layer number, and termination collectively influence the energy state of surface atoms. A relatively stable surface model was selected based on surface energy analysis. Since the surface energy differences among the 5-layer, 7-layer, and 9-layer structures of bcc-Fe are small, and the surface energy difference between the 7-layer and 9-layer structures of hcp-Zn is also small, the 5-a and 5-b surface models of bcc-Fe, as well as the 7-c, 7-d, and 7-f surface models of hcp-Zn, were chosen, as shown in

Figure 5.

3.2. Interface Model

As shown in

Figure 6, By constructing 5-layer surface models of bcc-Fe (labeled as 5-a and 5-b) and 7-layer surface models of hcp-Zn (labeled as 7-c, 7-d, and 7-f), the bcc-Fe/hcp-Zn interface models were further established using the supercell method with periodic boundary conditions (PBCs). A vacuum layer of 15 Å was still introduced into the interface models to avoid interatomic charge interactions between adjacent periodic images.

The model of the disordered solid solution consisting of the Fe matrix and Zn coating was adopted as part of the bonding interface. To clarify the optimal interfacial orientation relationship, extensive exploration and investigation of numerous potential crystallographic directions were conducted, with consideration given to the magnitude of interfacial misfit. Ultimately, the Fe(110)/Zn(101) interface model was selected in this study. Since misfit stress cannot be reduced merely by supercell expansion, a surface model reconstruction approach via redefining lattice parameters was employed to mitigate the misfit. Herein, the misfit degree is denoted as μ, calculated by the following formula [

26]:

wherein Ω denotes the interfacial coincidence area with a value of 30.55 Å

2;

A1 and

A2 represent the surface areas of the two phases composing the interface. After lattice reconstruction, the in-plane lattice lengths (u and v) of the Fe(110) surface structure are 11.287155 Å and 2.706237 Å, respectively, while those of the Zn(101) surface structure are 10.9173 Å and 2.8649 Å, respectively, with a 90° angle between u and v. Thus, the in-plane lattice parameters of Zn were constrained, resulting in a misfit degree of 1.18% for the Fe(110)/Zn(101) interface (a misfit degree less than 5% indicates a coherent interface). Additionally, the residual strain ultimately generated between the Fe layer and Zn layer is 0.24.

For the 6 constructed interface models, the interface spacing was manually adjusted to 1 Å, 1.2 Å, 1.4 Å, 1.6 Å, 1.8 Å, 2 Å, 2.2 Å, 2.4 Å, 2.6 Å, 2.8 Å, 3 Å, 3.2 Å, and 3.4 Å, respectively. The single-point energy of each of the 6 models was calculated under different spacing conditions, and finally, 6 stable interface models under the optimal spacing were obtained.

The work of adhesion (

Wsep) is an indicator for measuring the interfacial bonding strength between two materials. It represents the reversible work required to separate an interface from a bonded state into two independent free surfaces [

27]. A larger value of the work of adhesion indicates that the atoms at the interface are bonded more tightly, the bonding interaction between interfacial atoms is stronger, and the stability of the interface is higher. The calculation can be performed using the following formula [

28]:

in which

Eα and

Eβ represent the total energy of the free surfaces of the two phases after relaxation,

Eα/β represents the total energy of the relaxed interface, and

A represents the interface area.

The interfacial energy (

γint) is the increment of the free energy per unit interface system. A higher interfacial energy indicates that more energy is required to form the interface, and the interface is more unstable; therefore, a smaller interfacial energy corresponds to a more stable interface [

29]. The calculation can be performed using the following formula [

30,

31]:

in which

γα and

γβ represent the surface energies of the cross-sections of the α-phase and β-phase, respectively, and

wsep represents the work of adhesion at the interface formed by the α-phase and β-phase.

As shown in

Figure 7a, the adhesion work of the six interface models exhibits an overall trend of first remaining stable and then rising rapidly from Model 1 to Model 6. Combined with

Table 1, the adhesion work values of Models 1–3 stabilize at approximately 2.07 J/m

2, indicating that the adhesive interaction at the Fe-Zn interface is relatively stable for these three models. Starting from Model 3 to Model 4, the adhesion work increases sharply, and the subsequent Models 4–6 show a continuous upward trend. This reflects that the variation in the models has a significant impact on the bonding force at the Fe-Zn interface, enhancing the adhesion.

As shown in

Figure 7b, the interfacial energy of the six interface models exhibits an overall trend of first remaining stable and then decreasing rapidly from Model 1 to Model 6. Combined with

Table 1, the interfacial energy of Models 1–3 remains at approximately 1.8 J/m

2, a relatively stable value, indicating that the energy state of the Fe-Zn interface is stable under these three models, with minimal changes in interaction energy. Starting from Model 3 to Model 4, the interfacial energy decreases rapidly, and Models 4–6 show a continued downward trend, which suggests that the modification of the models promotes the Fe-Zn interface to tend toward a more stable state. a specific alloy phase with a special atomic configuration and ordered atomic arrangement are formed at the interface, which changes the energy state and makes the interface more stable. Meanwhile, the difficulty of separation increases. Therefore, Model 6, which has the highest Wsep and the lowest γ

int, is selected.

3.3. Si Element Doping

Based on the most stable bcc-Fe(110)/hcp-Zn(101) interface model (i.e., Interface 6) obtained in the previous section, the alloying element Si was doped at the interface. To facilitate calculations during the construction of the doped interface, alloy atoms were chosen to be doped into the interface through atomic substitution. Considering that atoms farther from the interface have a smaller impact on the interface, the first three atomic layers close to the interface were selected for Si atomic substitution at different positions. The substitution positions, namely Position 1, Position 2, Position 3, and Position 4, are shown in

Figure 8, depending on the specific atomic substitution sites.

Segregation energy refers to the amount of change in system energy when solute atoms deviate from a uniformly distributed state and enrich in specific regions (such as grain boundaries, dislocations) in an alloy or solid solution. It is a key energy indicator for determining whether solute atoms are prone to segregation [

29]. By calculating the segregation energy, the optimal substitution position of Si element in the bcc-Fe(110)/hcp-Zn(101) interface matrix is identified. The lower the segregation energy, the more likely segregation is to occur. The calculation formula of the heat of segregation can be transformed by the following equation [

32,

33,

34]:

: total energy of the clean SiC/Cu interface.

: total energy of the SiC/Cu interface doped with element X.

ECu: energy of a single Cu atom in the bulk Cu.

Enx: energy of a single X atom in the bulk X (X = Fe, W, Zr, Ti). By virtue of the relation that “chemical potential is equivalent to the energy of a single atom in the bulk phase”, the “expression based on total energy difference” is transformed into the “expression based on chemical potential difference”. The applicable calculation formula for the heat of segregation is as follows:

in which

denotes the total energy of the interface after doping with X atoms (X = Si or O);

Einterface denotes the total energy of the interface without Si and O doping; n is the number of doped atoms;

us and

ux are the chemical potentials of the substituted atom and the doped atom, respectively.

The calculation results of the segregation energy of Si element at different positions are shown in

Figure 8. It can be seen that the segregation energies of Si element are all negative, indicating that Si element tends to segregate at the interface. This is because the crystal structure, atomic radius, and electronic structure of Si element are similar to those of bcc-Fe. Position 1: The segregation energy is −1.59706 eV, meaning the segregation tendency of Si at this position is relatively weak. Position 2: The segregation energy is −1.78592 eV, the most negative among the four positions. This indicates that after Si substitutes Fe atoms at this Fe-Zn interface position, the segregation driving force is the largest, making it the easiest position for Si to segregate to. Position 3: The segregation energy is −1.64487 eV, showing that Si has a certain segregation tendency at this position, with the degree between that of Position 1 and Position 2. Position 4: The segregation energy is −1.6494 eV; the segregation tendency of Si at this position is close to that of Position 3 and slightly stronger than that of Position 1. it reflects that after Si substitutes different Fe positions, its segregation tendency at the Fe-Zn interface varies, and Position 2 is the most favorable for Si segregation. To reveal the local electronic structure effect, this study further investigates the bond population, differential charge density, and electronic properties of the doped models.

3.4. O Element Doping

Based on the crystal model of Position 2 doped with Si, the interstitial doping of O around Si was performed to simulate the oxide film structure of Si. According to the different doping positions of O atoms, their Position 5, Position 6, Position 7 and Position 8 are shown in

Figure 9.

In

Figure 9b, the segregation energy of Position 5 is −1.95566 eV, and that of Position 6 reaches −1.9903 eV, both of which are significantly negative and close to each other. This indicates that O atoms have a strong tendency to segregate at these two positions. Position 7 is −0.76973 eV and Position 8 is −0.76184 eV. The absolute values of the negative values are much smaller than those of the first two positions, and the two values are close to each other. The segregation driving force of O atoms at these two positions is weak, and the thermodynamic tendency of atomic enrichment is low. The chemical environment and atomic arrangement at the interface have little “binding force” on O, so O atoms are more likely to diffuse away or only segregate in small amounts. By analyzing

Figure 9c, it is found that the work of adhesion of the interface after doping is much smaller than that without doping. This indicates that the interfacial bonding force after doping is reduced, and the interfacial stability is decreased. Since the focus of this paper lies in the changes in interfacial stability, the reconstruction of the electronic structure before and after doping, and the bonding weakening mechanisms (such as charge density, bond population, DOS/PDOS, etc.), the core physical processes are mainly dominated by the changes in interfacial chemical bonding and orbital hybridization rather than the local magnetic moment of Fe. Furthermore, in the actual hot-dip galvanizing process, the contents of Si and O at the interface are usually extremely low, manifested primarily as local segregation. However, if the model is constructed strictly according to this extremely low actual concentration in first-principles calculations, it will require establishing an interfacial supercell with a huge size, leading to excessively high computational cost and extremely low efficiency. Therefore, single-atom substitution or interstitial doping is commonly adopted in DFT studies to simulate the local segregation behavior near the interface. Following this approach, the purpose of single-atom doping in this paper is not to replicate the overall compositional content in practical experiments, but to reveal the influence mechanisms of doping atoms on the electronic structure, bonding mode, and local stability within the interfacial microregion, including charge redistribution, changes in orbital hybridization, and perturbations in bond length and bond population. Thus, the core focus of the computational model is to investigate the local action mechanism of doping atoms rather than to simulate the global concentration level of real alloys. To reveal the local electronic structure effects, this paper further explores the bond population, differential charge density, and electrical properties of the doping models.

3.5. Bond Population

The bond population reflects the “strength” of bonding between atoms or the “degree of electron cloud overlap”. The degree of electron cloud overlap, namely the Mulliken overlap population, is intended to more intuitively characterize the variations in the strength of interatomic bonding as revealed by the Mulliken bond population. A positive bond population indicates an effective bonding interaction between atoms (good electron cloud overlap and stable bonding); a negative bond population usually means a weak interaction between atoms or even a repulsive interaction (poor electron cloud overlap and unstable bonding).

As shown in

Figure 10, the bond population of Fe-O shows a “weakening” trend (the positive layout decreases, or even approaches a negative value), which indicates that the bonding interaction between Fe and O is destroyed and the degree of electron cloud overlap decreases. The bond population of Si-Fe is a small positive value (or close to zero), suggesting that the bonding interaction between Si and Fe is weak and cannot effectively “anchor” the interface atoms. The core interface bonds Zn-Zn and Fe-Fe are the core interactions that maintain the stability of the Fe/Zn interface. After doping, the bond populations of Zn-Zn and Fe-Fe fluctuate (even negative layouts appear), which implies that the bonding interaction between interface atoms is disturbed and the electron cloud overlap deteriorates.

Bond length is negatively correlated with bonding strength: the longer the bond length, the weaker the bonding. The red curve in the figure represents the bond length. After doping, the bond lengths of key bonds (such as Fe-O and Si-Fe) increase, and the bonding strength of these bonds decreases—characterized by low electron cloud overlap and weakened binding force between atoms.

Interface stability depends on the “strong and ordered” bonding interaction between atoms (effective overlap of electron clouds to form a stable bonding network). After Si and O doping, the original bonding network of the Fe/Zn interface is destroyed (abnormal layout and length of core bonds); the newly formed bonds such as Si-Fe and Fe-O have weak interactions (low layout and long bond length) and cannot replace the stabilizing effect of the original bonds; the overall degree of electron cloud overlap between atoms decreases, and the “stability contribution” of bonding is insufficient. Eventually, the binding force between interface atoms weakens, leading to a reduction in interface stability.

3.6. Differential Charge

Charge density maps reflect the charge distribution within a system. In the pure Fe/Zn interface region, the charge distribution is relatively uniform, and there exists a certain charge interaction between Fe and Zn atoms, which maintains the stability of the interface. As shown in

Figure 11, after Si and O doping, observations of the charge density maps reveal localized regions of charge accumulation or depletion in the originally uniform charge distribution. Differential charge density maps can more clearly show the changes in charge before and after doping: red regions represent charge accumulation, while blue regions represent charge depletion. It can be seen from the figures that after Si and O doping, significant charge redistribution occurs around the doped atoms. The charge distribution in the region of charge interaction between Fe and Zn atoms changes; specifically, the charge density in the region where effective charge bonding originally existed between Fe and Zn atoms is altered. The charge transfer and redistribution patterns differ from those of the pure interface.

In the pure Fe/Zn interface, there are certain metallic bonds between Fe and Zn atoms. This interaction enables tight bonding between atoms and ensures interface stability. When Si and O are doped into the interface, they form new chemical bonds with surrounding Fe or Zn atoms. From the differential charge density maps in

Figure 11, it can be seen that the mode and strength of charge interaction between Si/O atoms and Fe/Zn atoms differ from those between Fe and Zn atoms. For example, O atoms attract surrounding charge, which affects the charge transfer between Fe and Zn atoms. The original distribution of bonding electron clouds between Fe and Zn is disrupted, leading to weakened bonding between Fe and Zn atoms. Meanwhile, the atomic radii of Si and O differ from those of Fe and Zn. The mismatch between the atomic radii of Si/O and Fe/Zn causes lattice distortion at the Fe/Zn interface after doping, generating internal stress. This internal stress disrupts the regularity of atomic arrangement at the interface, destabilizes the bonding between interface atoms, and thereby reduces the stability of the Fe/Zn interface. After doping, the differential charge density maps show an increase in the inhomogeneity of charge distribution. The emergence of charge accumulation and depletion regions destroys the balance of charge distribution at the interface—a balance that is crucial for interface stability. Imbalanced charge distribution weakens the interaction between interface atoms, further reducing the stability of the Fe/Zn interface. Si and O doping reduce the stability of the Fe/Zn interface by altering the chemical bonding at the interface, causing lattice distortion, and enhancing the inhomogeneity of charge distribution.

3.7. Electrical Properties

As shown in

Figure 12, before optimization (a), the following occurs: The total density of states exhibits a relatively high distribution near the Fermi level. This indicates that there are abundant electronic states around the Fermi level, and behaviors such as electron transitions near the Fermi level are relatively active. The electronic structure of the system provides a certain basis for electronic interactions to maintain interface stability. After optimization (b), the following occurs: Compared with that before optimization, the density of states near the Fermi level decreases, and the distribution shape of the density of states also changes. This means that after optimization, the number of electronic states near the Fermi level is reduced, and the electronic interactions around the Fermi level are weakened. Since the electronic states near the Fermi level are crucial for interactions such as bonding between atoms, this change will affect the stability of the interface.

As shown in

Figure 12, the partial density of states diagrams show the contribution of different atomic orbitals (s, p, d orbitals) to the density of states. Before optimization (c): The d orbital (blue curve) makes a significant contribution to the density of states near the Fermi level, while the s (black curve) and p (red curve) orbitals also make certain contributions. The d orbital of Fe atoms plays an important role in interactions such as metallic bonding. The distribution of these orbitals, especially the d orbital, near the Fermi level enables strong interactions between Fe and Zn atoms through orbital hybridization, thereby maintaining interface stability. After optimization (d): The contribution of the d orbital to the density of states near the Fermi level decreases significantly, and the contributions of the s and p orbitals also change. After Si and O doping, orbital interactions occur between Si/O atoms and Fe/Zn atoms, which alters the original density of states distribution of Fe and Zn atomic orbitals (especially the d orbital). As a result, the bonding interaction based on orbital hybridization between Fe and Zn atoms is weakened.

From the total density of states diagram, it can be observed that after optimization, the density of states near the Fermi level decreases, and interactions such as electron transitions around the Fermi level are weakened. However, interactions like bonding between atoms are closely related to the behavior of electrons near the Fermi level; the weakening of electron interactions leads to a reduction in the binding force between atoms. Meanwhile, the partial density of states diagrams show that after doping, the density of states distribution of orbitals such as the d-orbitals of Fe atoms near the Fermi level changes. Additionally, the hybridization between the orbitals of Si and O atoms (e.g., the p-orbitals of Si and the p-orbitals of O) and the orbitals of Fe and Zn atoms is altered. This disrupts the original effective orbital hybridization between Fe and Zn atoms, resulting in weakened chemical bonding interactions between atoms. Combined with the previous analysis related to charge density, Si and O doping causes charge redistribution, which further affects the electron cloud overlap between Fe and Zn atoms and the formation of chemical bonds. This leads to loose bonding between atoms at the interface, thereby reducing the stability of the Fe/Zn interface.

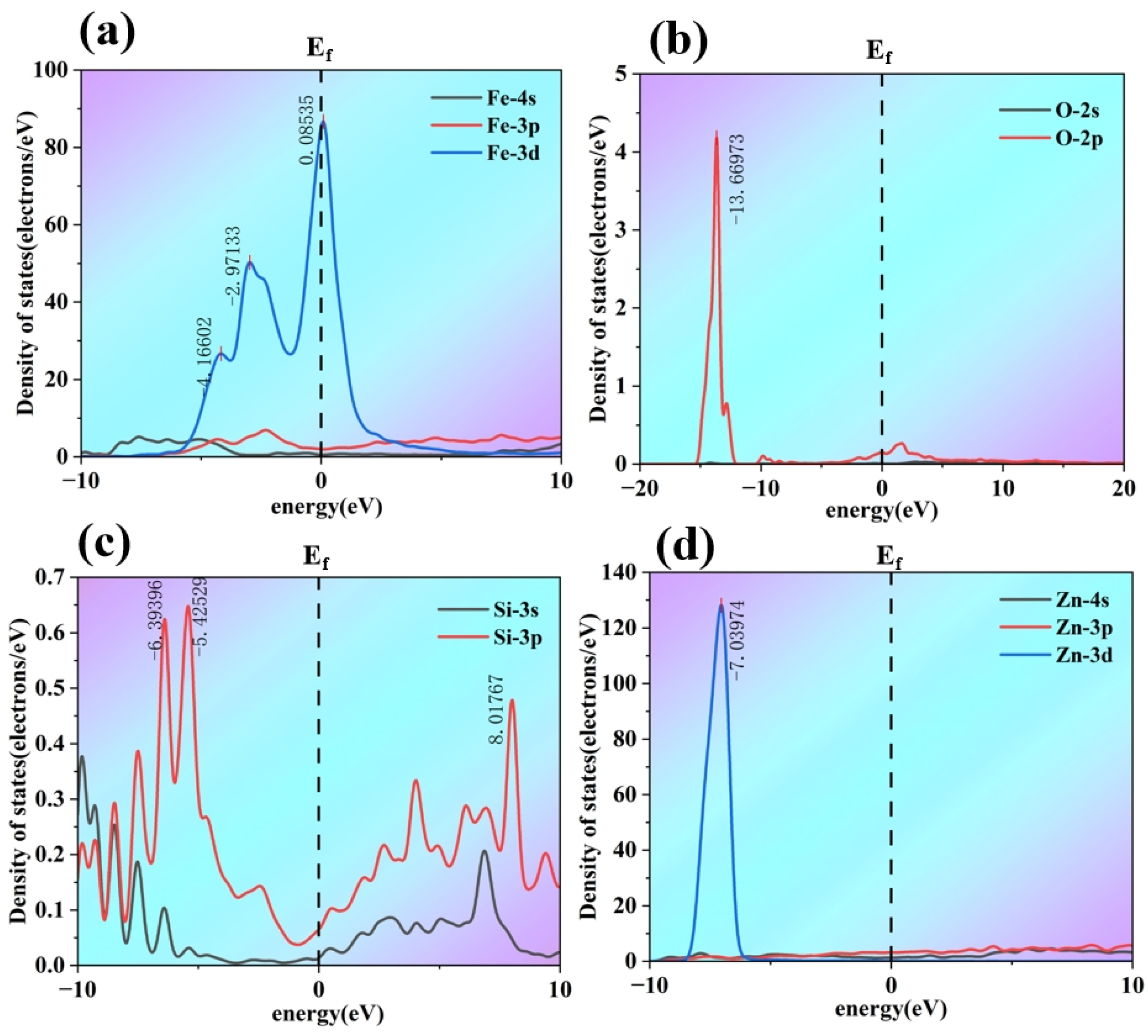

The partial density of states (PDOS) for each element is shown in

Figure 13. For Fe, in the PDOS distributions of the 4s, 3p, and 3d orbitals, the 3d orbital makes a significant contribution to the density of states near the Fermi level, while the 4s and 3p orbitals also contribute to some extent. At the Fe/Zn interface, the d orbitals of Fe play a key role in interactions such as metallic bonding; the distribution and interaction of their electrons are important factors in maintaining interface stability. For O, the PDOS distribution of the 2s and 2p orbitals shows that the 2p orbital exhibits a high density-of-states peak in the region below the Fermi level. As a dopant atom, the 2p orbitals of O interact with the orbitals of neighboring Fe and Zn atoms, thereby influencing the electronic structure at the interface. The PDOS distribution of Si’s 3s and 3p orbitals is relatively complex. The 3p orbital displays a density-of-states distribution over a wide energy range and also contributes moderately near the Fermi level. After Si doping, its 3p orbitals interact with the orbitals of Fe and Zn atoms—including hybridization—thereby modifying the electronic states at the interface. For Zn, in the PDOS distributions of the 4s, 3p, and 3d orbitals, the 3d orbital exhibits a distinct density-of-states peak near the Fermi level, while the 4s orbital also makes a certain contribution. The orbital electrons of Zn interact with those of Fe, collectively maintaining the stability of the Fe/Zn interface.

The 2p orbitals of O and the 3p orbitals of Si hybridize with the 3d orbitals of Fe, and the 3d and 4s orbitals of Zn. From the density of states (DOS) plots, the orbital DOS of O and Si overlap with those of Fe and Zn near the Fermi level. Such hybridization modifies the original orbital hybridization between Fe and Zn atoms. Originally, Fe and Zn atoms formed metallic bonding and other interactions through hybridization of their own orbitals (e.g., Fe 3d with Zn 3d and 4s). However, the introduction of O and Si orbitals disrupts these interactions, leading to a weakening of interatomic bonding. The DOS of Fe’s 3d orbitals near the Fermi level, as well as that of Zn’s 3d and 4s orbitals near the Fermi level, interact with the orbitals of O and Si after doping, thereby reducing the effective electron interactions in this energy region. The electronic states near the Fermi level are crucial for interatomic bonding; a reduction in electron interactions directly results in weaker bonding between interfacial atoms. In combination with charge density analysis, O and Si doping induces a redistribution of charge at the interface. O, with its high electronegativity, attracts surrounding charge. Si also differs in electronegativity from Fe and Zn. These differences cause changes in the electron cloud distribution between Fe and Zn atoms, reducing the overlap of electron clouds in the original chemical bonds (such as metallic bonds) between Fe and Zn, weakening the bond strength, and consequently lowering the stability of the Fe/Zn interface.

Electronic structure analysis reveals that the segregation of Si and O weakens the interfacial Fe–Zn bonding, reduces the work of adhesion, and induces local charge redistribution and orbital hybridization disruption. These microscale changes are consistent with common macroscopic defects in hot-dip galvanized coatings, such as decreased interfacial adhesion, increased coating spallation tendency, and enhanced brittleness. It is evident that the weakening of the interfacial electronic structure caused by Si/O doping is a crucial microstructural reason for the deterioration of coating bonding performance, providing theoretical support for understanding the failure mechanism of hot-dip galvanized interfaces.