Environmentally Durable Au-Based Low-e Coatings

Abstract

1. Introduction

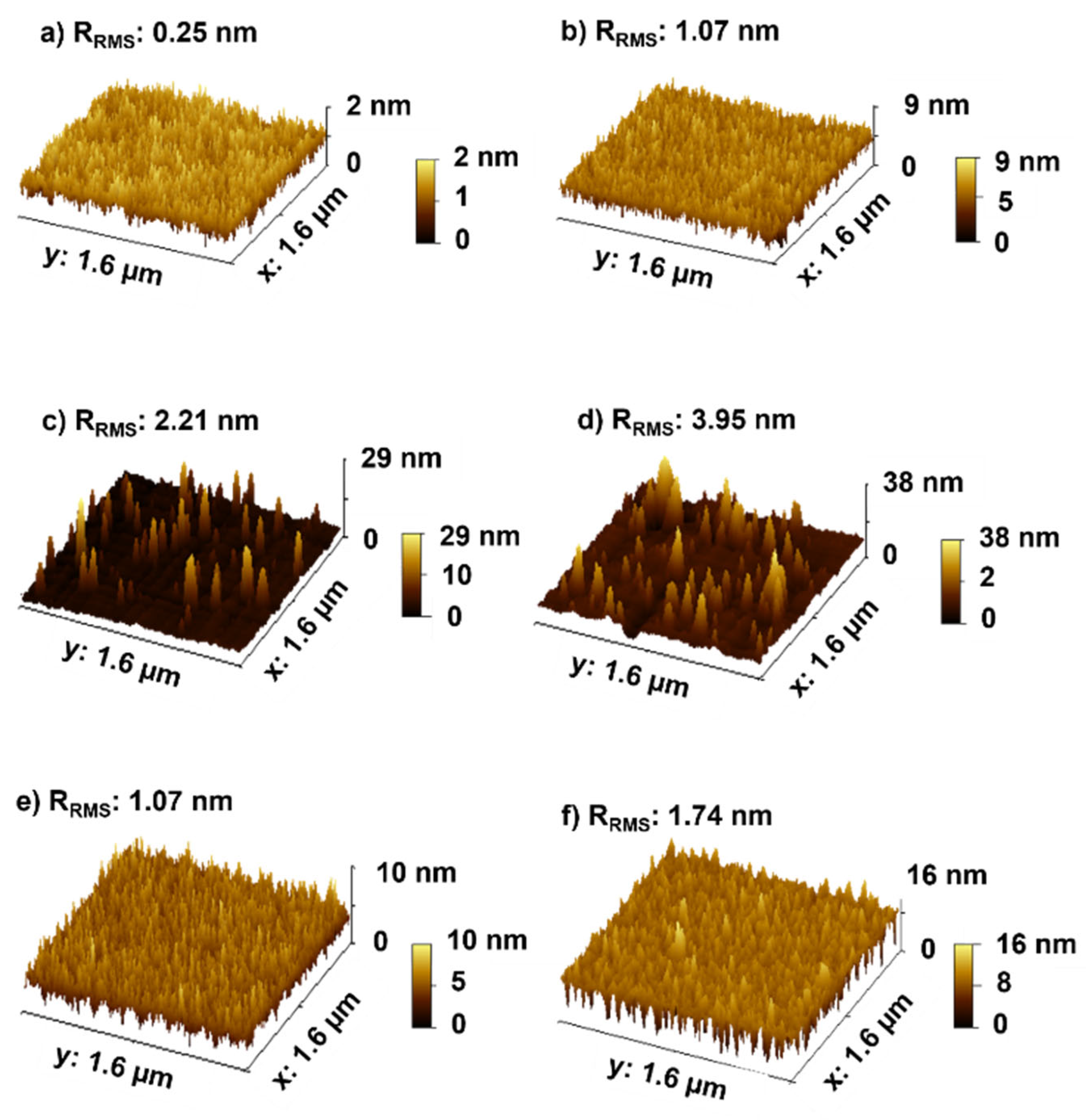

2. Experimental Procedure

2.1. Sample Preparation

2.2. Sample Characterisation

2.2.1. Optical and Electrical Properties

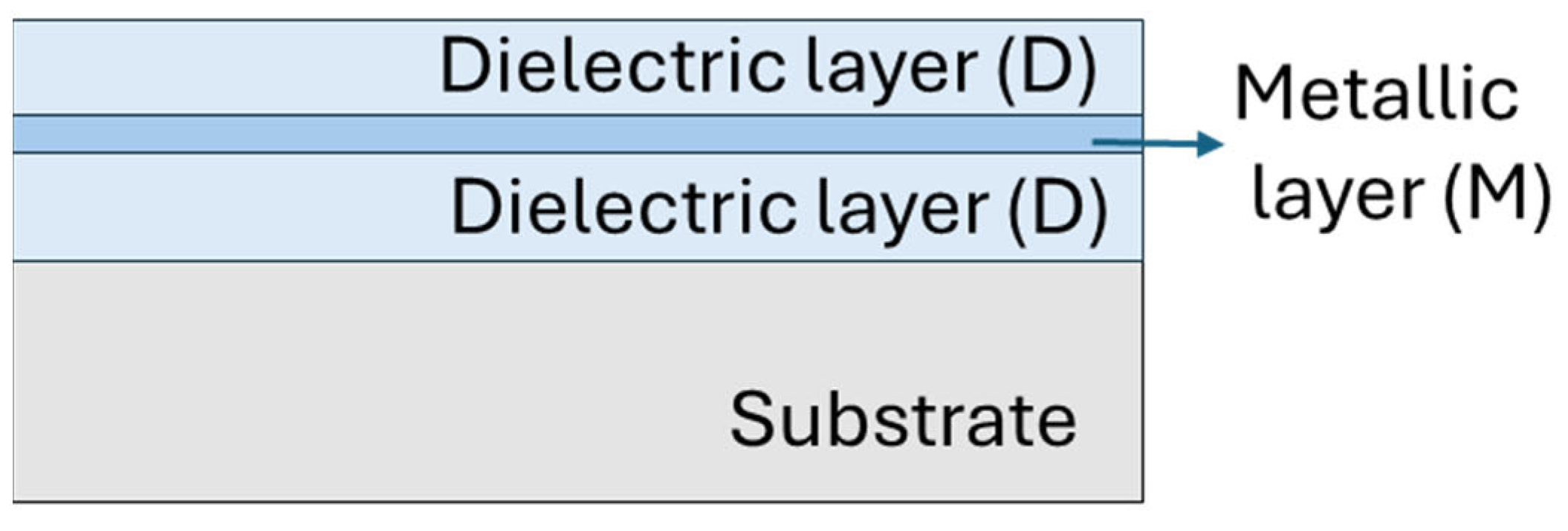

2.2.2. Morphology

2.2.3. Abrasion Resistance and Adhesion

2.2.4. Corrosion Resistance

3. Results and Discussion

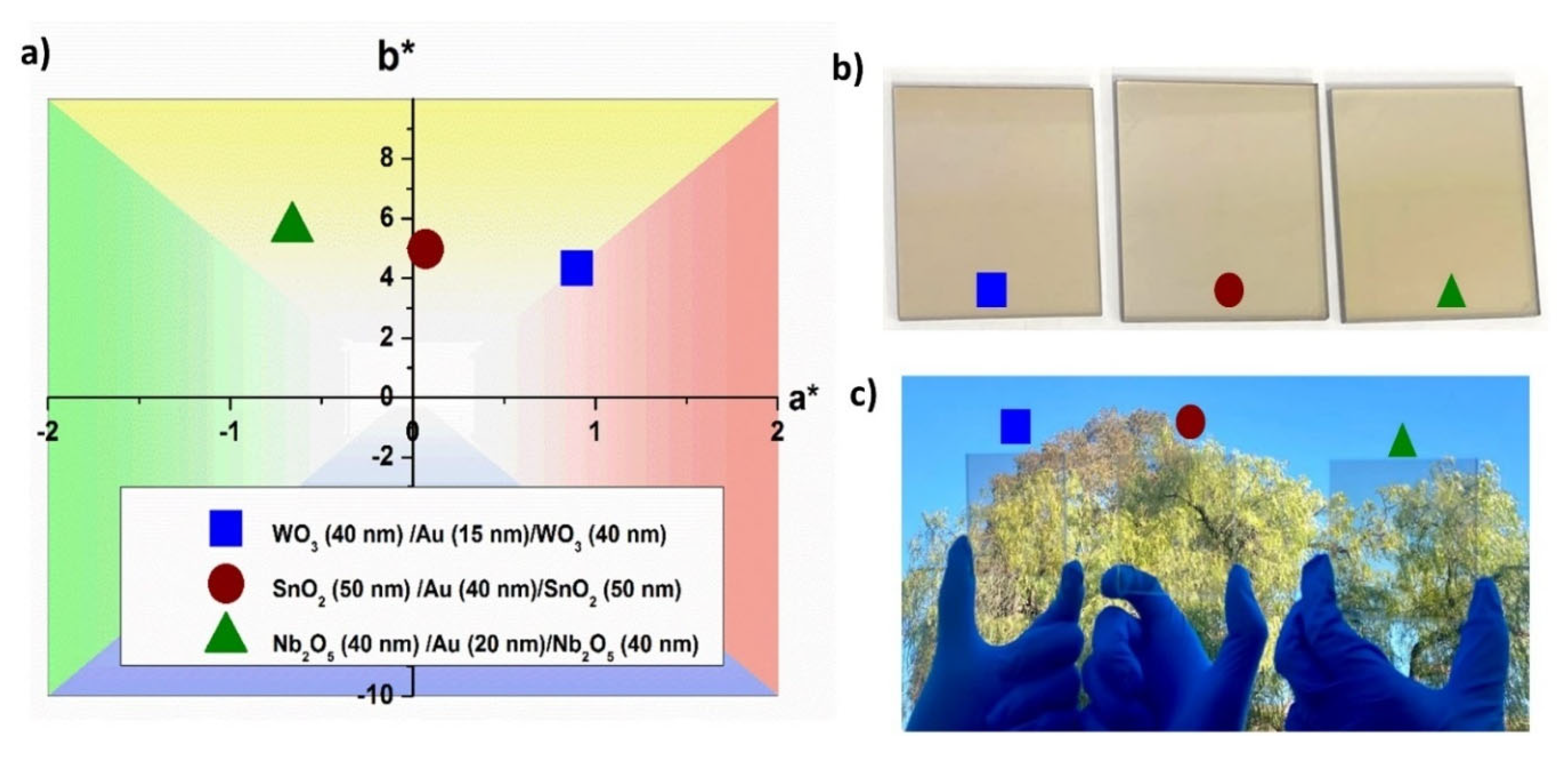

3.1. Optical Analysis

3.1.1. Metallic Layer

3.1.2. Dielectric Layer

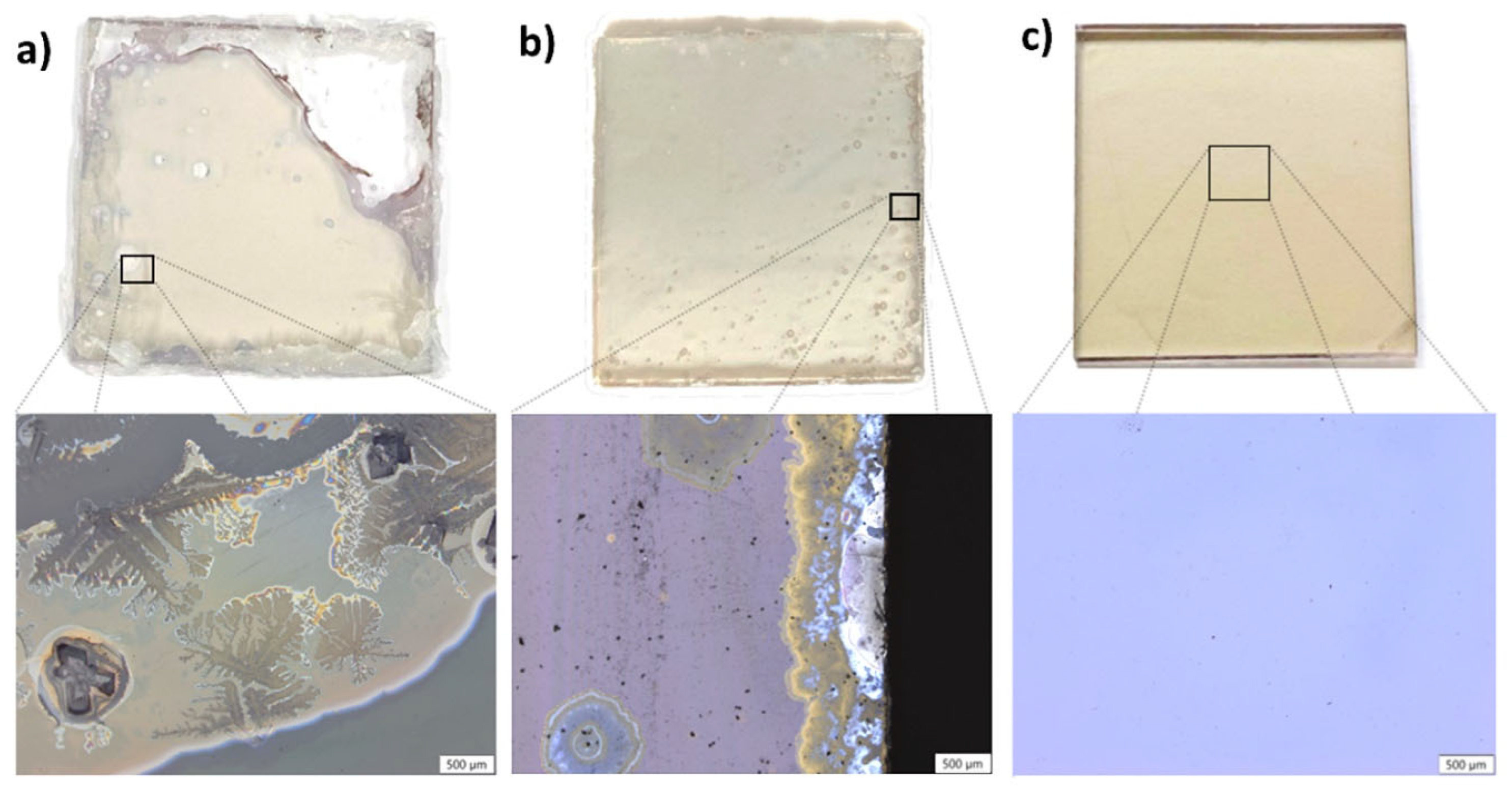

3.2. Environmental Durability

| WO3/Au/WO3 | SnO2/Au/SnO2 | Nb2O5/Au/Nb2O5 |

|---|---|---|

|  |  |

| ΔTvis = −12%, ΔRIR = −54% | ΔTvis = 0%, ΔRIR = −2% | ΔTVvis= 0%, ΔRIR = 0% |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amirkhani, S.; Bahadori-Jahromi, A.; Mylona, A.; Godfrey, P.; Cook, D. Impact of low-e window films on energy consumption and CO2 emissions of an existing UK hotel building. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Clavero, C. Silver-Based Low-Emissivity Coating Technology for Energy-Saving Window Applications. In Modern Technologies for Creating the Thin-Film Systems and Coatings; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Dalapati, G.K.; Kushwaha, A.K.; Sharma, M.; Suresh, V.; Shannigrahi, S.; Zhuk, S.; Masudy-Panah, S. Transparent heat regulating (THR) materials and coatings for energy saving window applications: Impact of materials design, micro-structural, and interface quality on the THR performance. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 95, 42–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalapati, G.K.; Masudy-Panah, S.; Chua, S.T.; Sharma, M.; Wong, T.I.; Tan, H.R.; Chi, D. Color tunable low cost transparent heat reflector using copper and titanium oxide for energy saving application. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelle, B.P.; Kalnæs, S.E.; Gao, T. Low-emissivity materials for building applications: A state-of-the-art review and future research perspectives. Energy Build. 2015, 96, 329–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, D.R.; Huang, J.L. Design of ZnO/Ag/ZnO multilayer transparent conductive films. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2006, 130, 295–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, D.R.; Huang, J.-L. High quality transparent conductive ZnO/Ag/ZnO multilayer films deposited at room temperature. Thin Solid Film. 2006, 515, 876–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neghabi, M.; Behjat, A.; Ghorashi, S.; Salehi, S. The effect of annealing on structural, electrical and optical properties of nanostructured ZnS/Ag/ZnS films. Thin Solid Film. 2011, 519, 5662–5666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-W.; Yang, R.-Y.; Hsiung, C.-M.; Chu, C.-H. Influence of Ag thickness of aluminum-doped ZnO/Ag/aluminum-doped ZnO thin films. Thin Solid Film. 2012, 520, 7147–7152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, G.; Clavero, C.; Schweigert, D.; Le, M. Thickness and microstructure effects in the optical and electrical properties of silver thin films. AIP Adv. 2015, 5, 117234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Alford, T.L. The optimal TiO2/Ag/TiO2 electrode for organic solar cell application with high device-specific Haacke figure of merit. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2016, 157, 599–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, A.; Asokan, K.; Sachdev, K. High-performance radiation stable ZnO/Ag/ZnO multilayer transparent conductive electrode. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2017, 169, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur-E-Alam, M.; Vasiliev, M.; Alameh, K. Dielectric/metal/dielectric (DMD) multilayers: Growth and stability of ultra-thin metal layers for transparent heat regulation (THR). In Energy Saving Coating Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 83–112. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Lee, J.L. Design of dielectric/metal/dielectric transparent electrodes for flexible electronics. J. Photonics Energy 2012, 2, 021215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, R. Observations on humidity-induced degradation of Ag-based low-emissivity films. Sol. Energy Mater. 1990, 21, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, E.; Miyazaki, M. Moisture degradation mechanism of silver-based low-emissivity coatings. Thin Solid Film. 1999, 351, 308–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, W.N.S.W.; Roccisano, A.; Zuber, K.; Murphy, P.J.; Jane, M.L. Environmentally robust Ag–Cu based low-e coatings. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 248, 112033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuhaili, M.F. Enhancement of plasmonic transmittance of porous gold thin films via gold/metal oxide bi-layers for solar energy-saving applications. Sol. Energy 2019, 181, 456–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, J.M.; Ashley, E. Infrared reflectance and emittance of silver and gold evaporated in ultrahigh vacuum. Appl. Opt. 1965, 4, 221–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, L.; Siddall, G. Heat-reflecting windows using gold and bismuth oxide films. Br. J. Appl. Phys. 1958, 9, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Kuhaili, M.; Al-Aswad, A.; Durrani, S.; Bakhtiari, I. Energy-saving transparent heat mirrors based on tungsten oxide–gold WO3/Au/WO3 multilayer structures. Sol. Energy 2012, 86, 3183–3189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, K.E.; Veszelei, M.; Roos, A. Zirconium nitride based transparent heat mirror coatings—Preparation and characterisation. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 1994, 32, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuddin, W.N.S.W.; Zuber, K.; Murphy, P.J.; Jane, M.L. Environmental durability of soft low-e coatings: A review. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 266, 112673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, A.; Patel, A.; Purohit, R. An overview of Polymeric Materials for Automotive Applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2017, 4, 3807–3815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovyev, A.; Rabotkin, S.; Kovsharov, N. Polymer films with multilayer low-E coatings. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2015, 38, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pracchia, J.A.; Simon, J.M. Transparent heat mirrors: Influence of the materials on the optical characteristics. Appl. Opt. 1981, 20, 251–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leftheriotis, G.; Yianoulis, P.; Patrikios, D. Deposition and optical properties of optimised ZnS/Ag/ZnS thin films for energy saving applications. Thin Solid Film. 1997, 306, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, N.; Ismail, N.; Nuruzzaman, D. Preparation of tin oxide (SnO2) thin films using thermal oxidation. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 319, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnanam, S.; Rajendran, V. Luminescence properties of EG-assisted SnO2 nanoparticles by sol-gel process. Dig. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2010, 5, 699–704. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xin, Q.; Du, L.; Qu, Y.; Li, H.; Kong, X.; Wang, Q.; Song, A. Extremely Sensitive Dependence of SnOx Film Properties on Sputtering Power. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 36183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wissmann, P.; Finzel, H.-U. Electrical Resistivity of Thin Metal Films; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 223. [Google Scholar]

- James, R.A.; Stapleton, A.J.; Hughes, A.; Charrault, E.; Zuber, K.; Switalska, E.; Evans, D.; Murphy, P.; Llusca, M. Metallic Adhesive Layers for Ag-Based First Surface Mirrors. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2018, 20, 1800106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

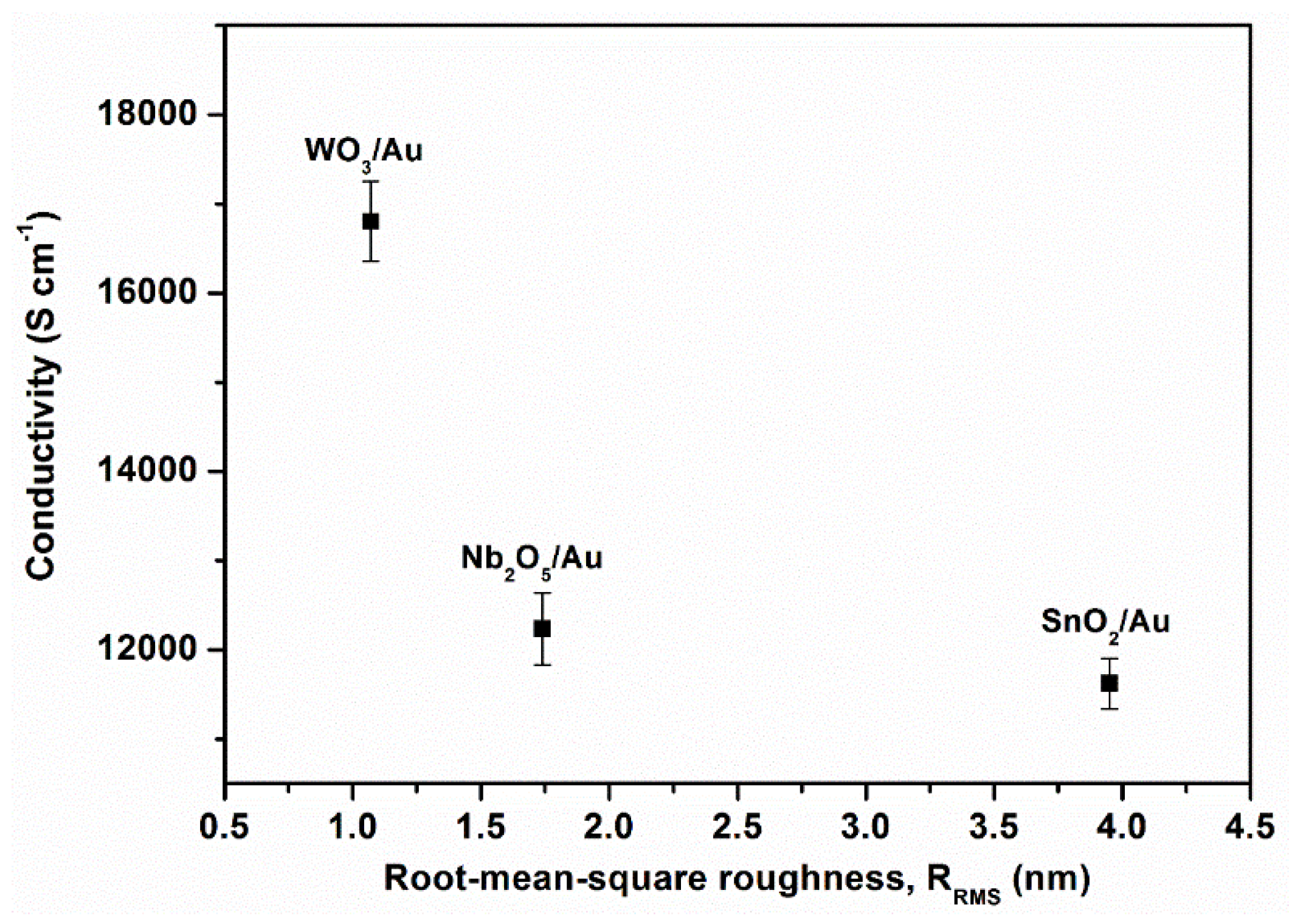

- Zhou, T.; Zheng, P.; Pandey, S.C.; Sundararaman, R.; Gall, D. The electrical resistivity of rough thin films: A model based on electron reflection at discrete step edges. J. Appl. Phys. 2018, 123, 155107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakanishi, Y.; Kato, K.; Omoto, H.; Tomioka, T. Improvement in salt-water durability of Ag thin films deposited by magnetron sputtering using argon and nitrogen mixed gas. Vacuum 2013, 87, 232–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lansåker, P.; Backholm, J.; Niklasson, G.; Granqvist, C. TiO2/Au/TiO2 multilayer thin films: Novel metal-based transparent conductors for electrochromic devices. Thin Solid Film. 2009, 518, 1225–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köstlin, H.; Frank, G. Optimization of transparent heat mirrors based on a thin silver film between antireflection films. Thin Solid Film. 1982, 89, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyce, P.; Eklund, N.; Mangum, S.; Saalfield, C.; Tang, L. Minimum acceptable transmittance of glazing. Int. J. Light. Res. Technol. 1995, 27, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dresselhaus, M.; Dresselhaus, G.; Cronin, S.B.; Filho, A.G.S. Drude theory–free carrier contribution to the optical properties. In Solid State Properties: From Bulk to Nano; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 329–344. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, C.; Liu, J.; Wang, J.; Gu, Z.; Li, C.; Li, Q.; Li, Y.; Zhang, S.; Bi, C.; Fan, X.; et al. New design for highly durable infrared-reflective coatings. Light Sci. Appl. 2018, 7, 17175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vernardou, D.; Drosos, H.; Spanakis, E.; Koudoumas, E.; Katsarakis, N.; Pemble, M. Electrochemical properties of amorphous WO3 coatings grown on polycarbonate by aerosol-assisted CVD. Electrochim. Acta 2012, 65, 185–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salunkhe, P.; AV, M.A.; Kekuda, D. Structural, spectroscopic and electrical properties of dc magnetron sputtered NiO thin films and an insight into different defect states. Appl. Phys. A 2021, 127, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantinidis, S.; Dauchot, J.; Hecq, M. Titanium oxide thin films deposited by high-power impulse magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Film. 2006, 515, 1182–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koski, K.; Hölsä, J.; Juliet, P. Properties of aluminium oxide thin films deposited by reactive magnetron sputtering. Thin Solid Film. 1999, 339, 240–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jane, M.L.; Hall, C.; Pająk, A.; Patil, A.; Switalska, E.; Yunos, L.N.; Reeks, L.B.; Zuber, K. Coated Articles with A Low-E Coating and/or A Hard Coat. Australian Provisional Patent Application AU2022901475A0, 31 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, K.; Shimada, K.; Fukuda, S. Aggregation in thin-film silver: Induced by chlorine and inhibited by alloying with two dopants. Corros. Sci. 2009, 51, 2557–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Dong, Y.; Li, X.; Gao, Y.; He, W.; Liu, Y.; Mu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Fu, W.; Wang, X.; et al. Development of a mechanically robust superhydrophobic anti-corrosion coating using micro-hBN/nano-Al2O3 with multifunctional properties. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 491–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material | Power (W) | Ar (sccm) | O2 (sccm) | Working Pressure (mbar) | Deposition Rate (nm/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Au | 300 | 15 | 0 | 3.0 × 10−3 | 7.32 |

| WO3 | 200 | 15 | 50 | 6.5 × 10−3 | 0.84 |

| SnO2 | 50 | 15 | 23 | 4.0 × 10−3 | 0.72 |

| Nb2O5 | 1500 | 50 | 70 | 3.3 × 10−3 | 4.67 |

| SiO2 | 2000 | 230 | 45 | 3.3 × 10−3 | 6.67 |

| Thickness of Au Layers (nm) | Standard Deviation (nm) | Tvis (%) | RIR (%) | Փ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO3(40 nm)/Au/WO3 (40 nm) | ||||

| 10 | 1.26 | 73 | 35 | 0.26 |

| 15 | 0.75 | 63 | 63 | 0.40 |

| 17 | 0.82 | 57 | 70 | 0.40 |

| SnO2 (40 nm)/Au/SnO2 (40 nm) | ||||

| 10 | 0.89 | 69 | 15 | 0.10 |

| 20 | 1.03 | 67 | 40 | 0.27 |

| 30 | 1.04 | 62 | 51 | 0.32 |

| 40 | 1.32 | 53 | 71 | 0.38 |

| 45 | 1.41 | 29 | 87 | 0.25 |

| Nb2O5 (40 nm)/Au/Nb2O5 (40 nm) | ||||

| 10 | 1.17 | 70 | 21 | 0.15 |

| 15 | 1.05 | 66 | 63 | 0.42 |

| 20 | 0.75 | 56 | 76 | 0.43 |

| 25 | 1.03 | 48 | 83 | 0.40 |

| Thickness of Dielectric Layer (nm) | Standard Deviation (nm) | Tvis(%) | RIR(%) | Փ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WO3/Au (15 nm)/WO3 | ||||

| 30 | 1.47 | 54 | 69 | 0.37 |

| 35 | 0.82 | 57 | 69 | 0.39 |

| 40 | 1.03 | 63 | 63 | 0.40 |

| 45 | 1.17 | 63 | 62 | 0.39 |

| SnO2/Au (40 nm)/SnO2 | ||||

| 40 | 2.07 | 53 | 71 | 0.38 |

| 50 | 1.72 | 57 | 68 | 0.39 |

| 60 | 0.75 | 59 | 66 | 0.39 |

| Nb2O5/Au (20 nm)/Nb2O5 | ||||

| 35 | 1.47 | 51 | 79 | 0.40 |

| 40 | 1.03 | 56 | 76 | 0.43 |

| 50 | 0.75 | 60 | 72 | 0.43 |

| 60 | 1.37 | 60 | 66 | 0.40 |

| Δ H% | ||

|---|---|---|

| Multilayer Samples | Steel Wool | Bayer |

| Nb2O5/Au/Nb2O5 | 5.2 | 9.8 |

| Nb2O5/Au/Nb2O5/SiO2/HC | 1.5 | 5.9 |

| Commercial abrasion-resistant polycarbonate (Makrolon AR) | 0.9 | 3.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wan Shamsuddin, W.N.S.; Zuber, K.; Murphy, P.J.; Llusca Jane, M. Environmentally Durable Au-Based Low-e Coatings. Coatings 2025, 15, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15101231

Wan Shamsuddin WNS, Zuber K, Murphy PJ, Llusca Jane M. Environmentally Durable Au-Based Low-e Coatings. Coatings. 2025; 15(10):1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15101231

Chicago/Turabian StyleWan Shamsuddin, Wan Noor Sofia, Kamil Zuber, Peter J. Murphy, and Marta Llusca Jane. 2025. "Environmentally Durable Au-Based Low-e Coatings" Coatings 15, no. 10: 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15101231

APA StyleWan Shamsuddin, W. N. S., Zuber, K., Murphy, P. J., & Llusca Jane, M. (2025). Environmentally Durable Au-Based Low-e Coatings. Coatings, 15(10), 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15101231