3.6. Simulation Results (Rock/Liquid)

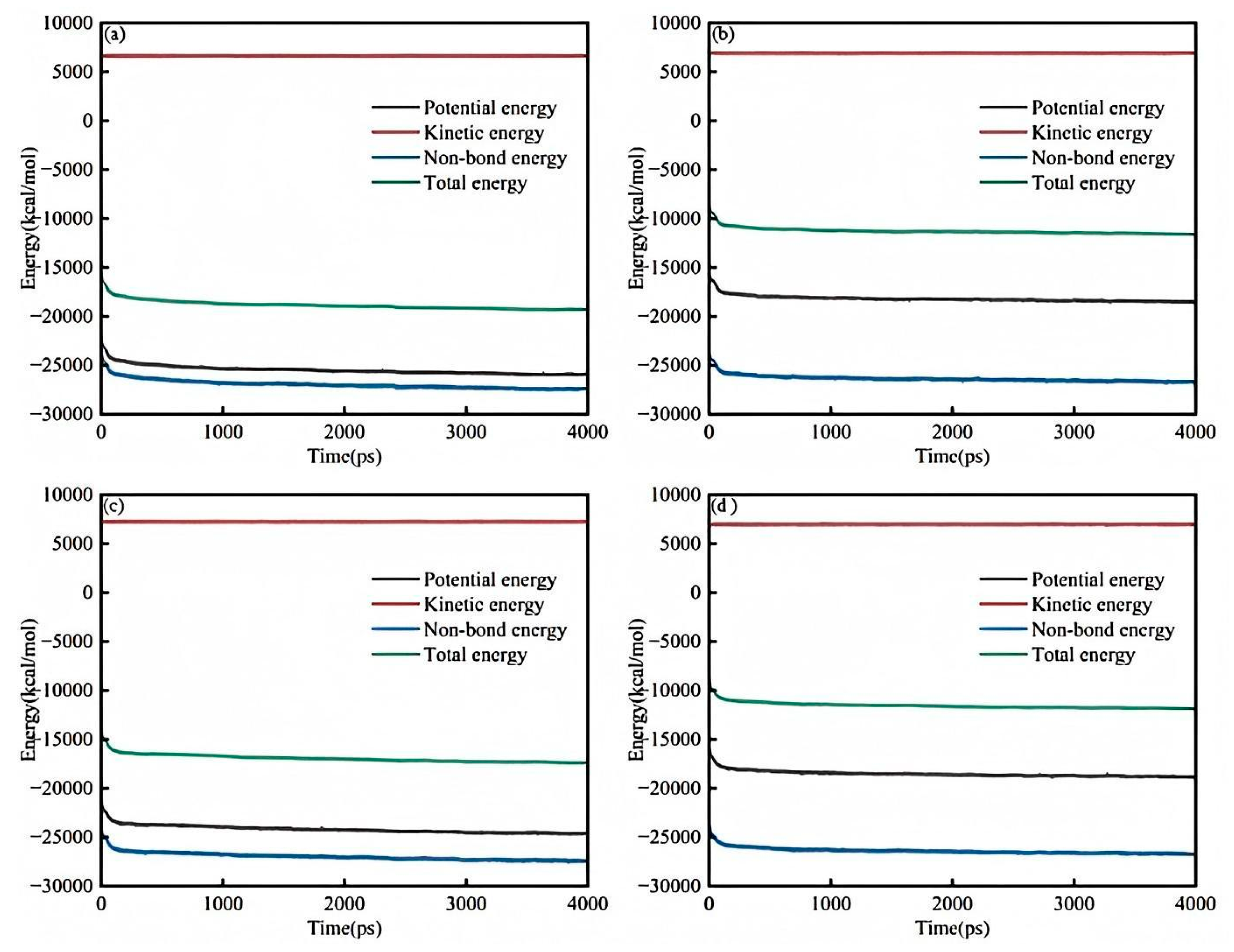

Figure 8a shows the energy balance diagram of the saturated component and the sodium laureth sulfate system. As can be seen from the figure, the energy fluctuates in the first 100 ps, and the energy is stable after 100 ps. When the simulation time is the same, the kinetic energy is the largest, followed by the total energy, the potential energy, and the smallest non-bond energy. When the simulation time is 4000 ps, the dynamic energy is stable at about 7000 kcal/mol, the total energy is stable at about −19,000 kcal/mol, the potential energy is stable at about −26,000 kcal/mol, and the non-energetic energy is stable at about −27,000 kcal/mol. The energy balance diagram shows that 4000 ps is sufficient to stabilize the simulation.

Figure 8b shows the energy balance diagram of the aromatic fraction and the sodium laureth sulfate system. As can be seen from the figure, the energy fluctuates in the first 100 ps, and the energy is stable after 100 ps. When the simulation time is the same, the kinetic energy is the largest, followed by the total energy, the potential energy, and the smallest non-bond energy. When the simulation time is 4000 ps, the dynamic energy is stable at about 7000 kcal/mol, the total energy is stable at about −12,000 kcal/mol, the potential energy is stable at −18,000 kcal/mol, and the non-energetic energy is stable at about −27,000 kcal/mol. The energy balance diagram shows that 4000 ps is sufficient to stabilize the simulation.

Figure 8c is a diagram of the energy balance between the colloid and sodium laureth sulfate system. As can be seen from the figure, the energy fluctuates in the first 100 ps, and the energy is stable after 100 ps. When the simulation time is the same, the kinetic energy is the largest, followed by the total energy, the potential energy, and the smallest non-bond energy. When the simulation time is 4000 ps, the dynamic energy is stable at about 7000 kcal/mol, the total energy is stable at −18,000 kcal/mol, the potential energy is stable at −25,000 kcal/mol, and the non-energetic energy is stable at about −28,000 kcal/mol. The energy balance diagram shows that 4000 ps is sufficient to stabilize the simulation.

Figure 8d is a diagram of the energy balance of asphaltene and the sodium laureth sulfate system. As can be seen from the figure, the energy fluctuates in the first 100 ps, and the energy is stable after 100 ps. When the simulation time is the same, the kinetic energy is the largest, followed by the total energy, the potential energy, and the smallest non-bond energy. When the simulation time is 4000 ps, the dynamic energy is stable at about 7000 kcal/mol, the total energy is stable at −12,000 kcal/mol, the potential energy is stable at −19,000 kcal/mol, and the non-energetic energy is stable at about −27,000 kcal/mol. The energy balance diagram shows that 4000 ps is sufficient to stabilize the simulation.

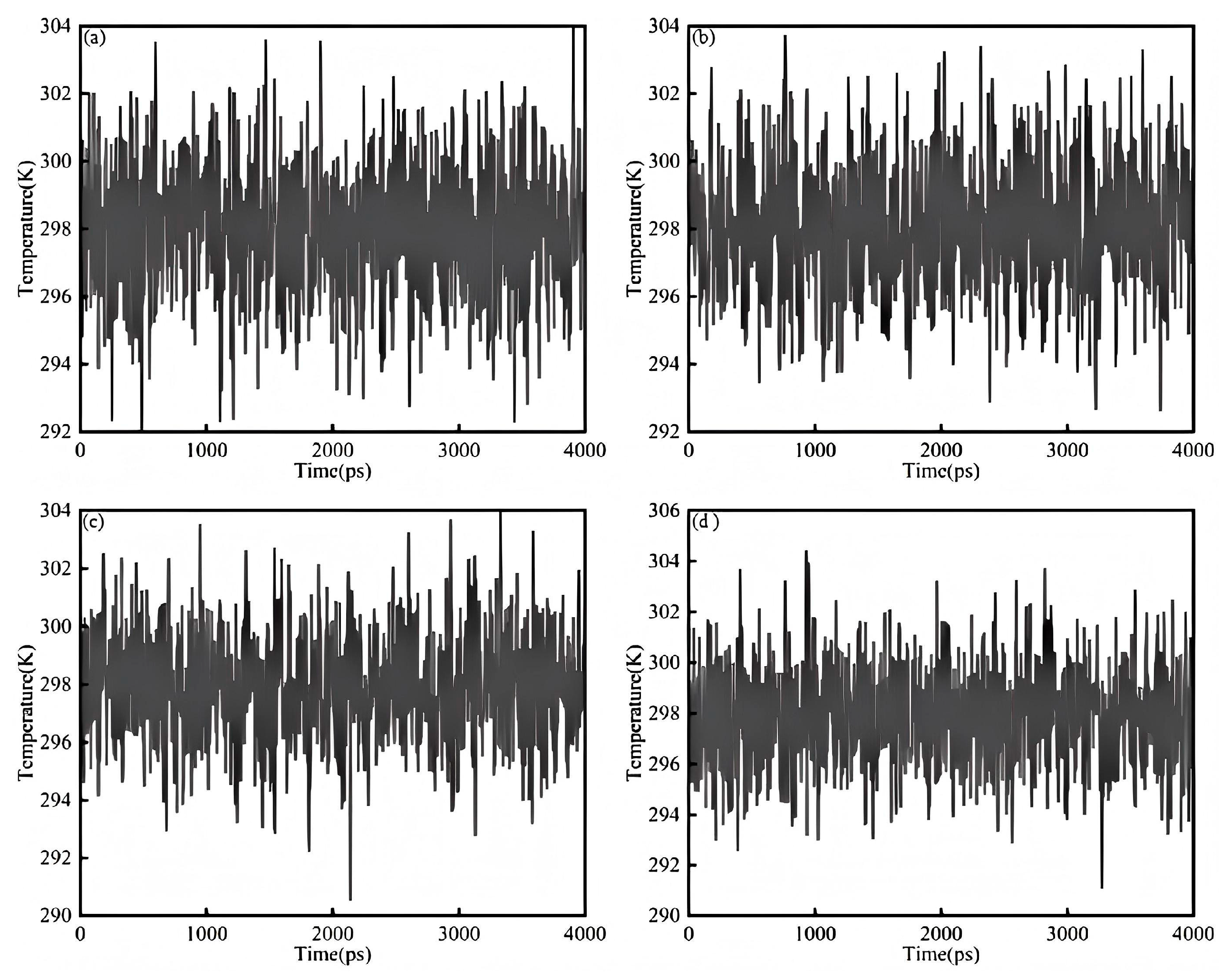

Figure 9a shows the temperature equilibrium diagram of the saturated component and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the temperature fluctuation range is from 292 K to 304 K and the overall temperature is around 298 K, indicating that the simulation has reached the temperature equilibrium state and the data is valid. The temperature range is within 0 to 4000 ps without major changes.

Figure 9b shows the temperature balance of aromatic components and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the temperature fluctuation range is from 292 K to 304 K and the overall temperature is around 298 K, indicating that the simulation has reached the temperature equilibrium state and the data is valid. The temperature range is within 0 to 4000 ps without major changes.

Figure 9c shows the temperature balance diagram of the colloid and sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the temperature fluctuation range is from 290 K to 304 K and the overall temperature is around 298 K, indicating that the simulation has reached the temperature equilibrium state and the data is valid. The temperature range is within 0 to 4000 ps without major changes.

Figure 9d shows the temperature equilibrium diagram of asphaltene and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the temperature fluctuation range is from 291 K to 305 K and the overall temperature fluctuation is around 298 K, indicating that the simulation has reached the temperature equilibrium state and the data is valid. The temperature range is within 0 to 4000 ps without major changes.

Figure 10a shows the MSD diffusion diagram of the saturated component and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the diffusion coefficient of the saturation component is greater than that of sodium laureth sulfate at 1800 ps to 3700 ps, and the diffusion coefficient of sodium laureth sulfate is greater than that of sodium laureth sulfate at the rest of the time. The diffusion of the saturation fraction increases with the increase in simulation time, the MSD value gradually increases, and when the simulation time is close to 2000 ps, the MSD coefficient rises faster. The MSD value of sodium laureth sulfate gradually rises with simulation time; when the simulation time is close to 3100 ps, the MSD coefficient rises more rapidly. This is because the simulation is unstable over short time frames, meaning the interaction between the saturation fraction and sodium laureth sulfate does not reach a stable value, and instead gradually increases.

Figure 10b is an MSD diffusion diagram of aromatic components and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the diffusion coefficient of sodium laureth sulfate is greater than that of the aromatic fraction. The diffusion of aromatic content is such that the MSD value gradually increases with the increase in simulation time, and the MSD coefficient increases rapidly when the simulation time is close to 3400 ps. The MSD value of sodium laureth sulfate increased gently with the simulation time; when the simulation time was close to 3500 ps, the MSD coefficient rises rapidly. This is because the simulation is unstable over short time frames, meaning the interaction between the aromatic content and sodium laureth sulfate does not reach a stable value, and instead gradually increases.

Figure 10c is an MSD diffusion diagram of the colloid and sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the diffusion coefficient of sodium laureth sulfate is greater than that of glia. The MSD value continued to increase with the increase in simulation time, and the MSD coefficient increased rapidly when the simulation time was close to 3300 ps. The MSD value of sodium laureth sulfate rises gently with the simulation time; when the simulation time is close to 3600 ps, the MSD coefficient rises rapidly. At the same time, the interaction between the glia and sodium laureth sulfate did not reach a stable value, meaning it gradually increased.

Figure 10d is an MSD diffusion diagram of asphaltene and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the diffusion coefficient of sodium laureth sulfate is greater than that of asphaltene. The diffusion of asphaltene causes a gradual increase in MSD value as the simulation time increases, and the MSD coefficient increases rapidly when the simulation time is close to 3100 ps. The MSD value of sodium laureth sulfate increased steadily with the simulation time and increased rapidly when the simulation time was close to 3300 ps. This is because the simulation is unstable over short time frames, meaning the interaction between asphaltene and sodium laureth sulfate does not reach a stable value, and instead gradually increases.

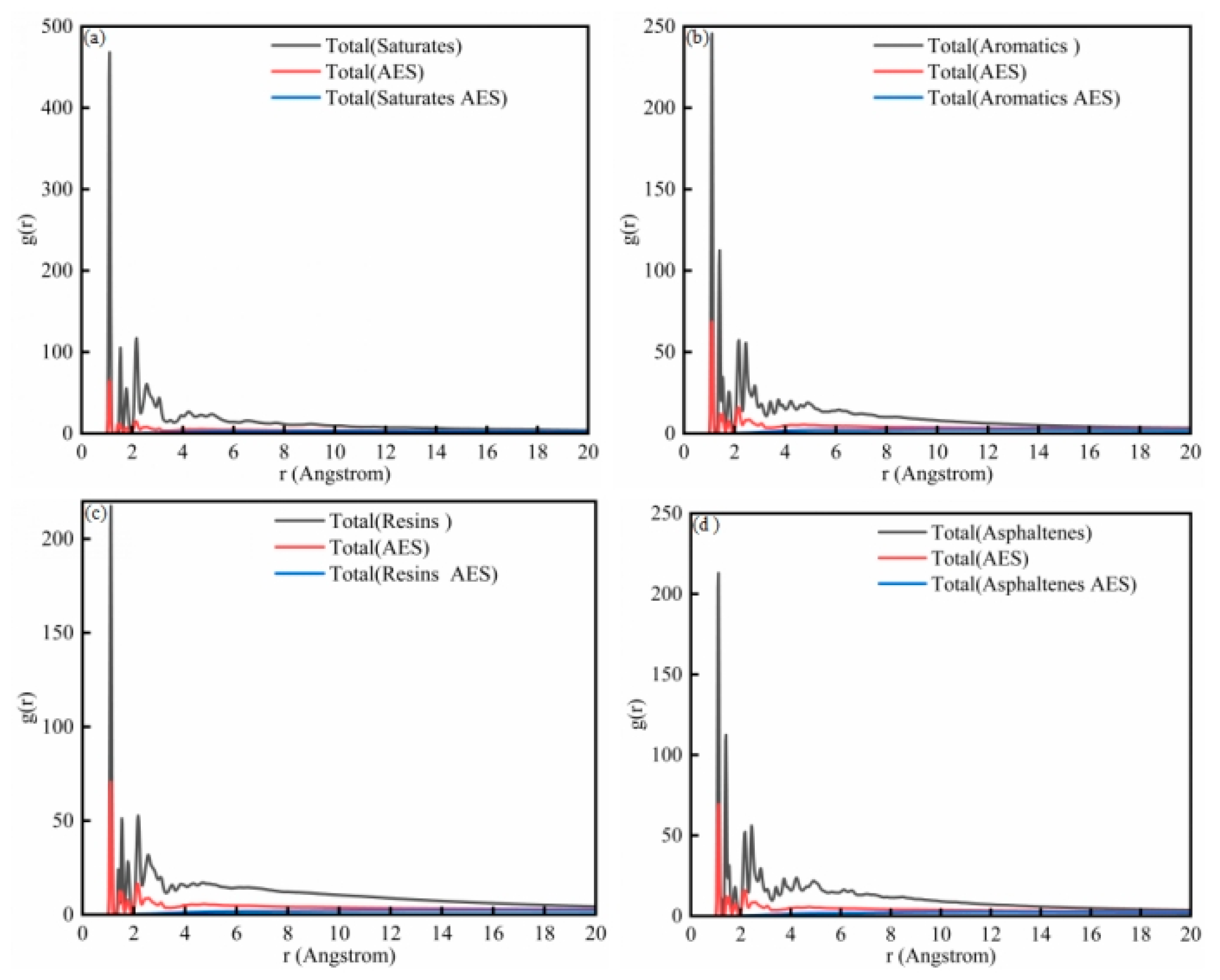

Figure 11a shows the RDF plot of the saturated component and the sodium laureth sulfate system. For the saturation fraction, there are three main peaks, with peak positions of 1.1 A, 1.5 A, and 2.2 A, respectively. For sodium laureth sulfate, a major peak position occurs at 1.1 A. The results of the radial distribution function show that the relative positions of the interactions between the saturated atoms are higher than those between sodium laureth sulfate. The total blue curve, the saturation fraction and sodium laureth sulfate plot, show that there is no obvious peak between the saturated molecule and the sodium laureth sulfate molecule as a whole, and the peak position reaches equilibrium after 7 A.

Figure 11b is the RDF diagram of the aromatic component and sodium laureth sulfate system. For aromatic components, there are four main peaks, with peak positions of 1.1 A, 1.4 A, 2.2 A, and 2.5 A, respectively. For sodium laureth sulfate, a major peak position occurs at 1.1 A. The results of the radial distribution function show that the relative position of the interaction between the aromatic atoms is higher than that between sodium laureth sulfate. The total blue curve, the plot of the aromatic fraction and sodium laureth sulfate, shows that there is no obvious peak between the aromatic molecule and the sodium laureth sulfate molecule as a whole, and the peak position reaches equilibrium after 7 A.

Figure 11c is an RDF diagram of the colloid and sodium laureth sulfate system. For glia, there are three main peaks, with peak positions of 1.1 A, 1.5 A, and 2.2 A, respectively. For sodium laureth sulfate, a major peak position occurs at 1.1 A. The results of the radial distribution function show that the relative position of the interaction between the colloidal atoms is higher than that between sodium laureth sulfate. The total blue curve, the graph of the colloid and sodium laureth sulfate, shows that there is no obvious peak between the colloid and sodium laureth sulfate molecules as a whole, and the peak position reaches equilibrium after 6 A.

Figure 11d is the RDF diagram of asphaltene and the sodium laureth sulfate system. For asphaltene, there are four main peaks, with peak positions of 1.1 A, 1.4 A, 2.2 A, and 2.4 A, respectively. For sodium laureth sulfate, a major peak position occurs at 1.1 A. The results of the radial distribution function show that the relative positions of the interactions between asphaltene atoms are higher than those between sodium laureth sulfate. The overall blue curve, the graph of asphaltene and sodium laureth sulfate, shows that there is no obvious peak between the asphaltene molecule and the sodium laureth sulfate molecule as a whole, and the peak position reaches equilibrium after 7 A.

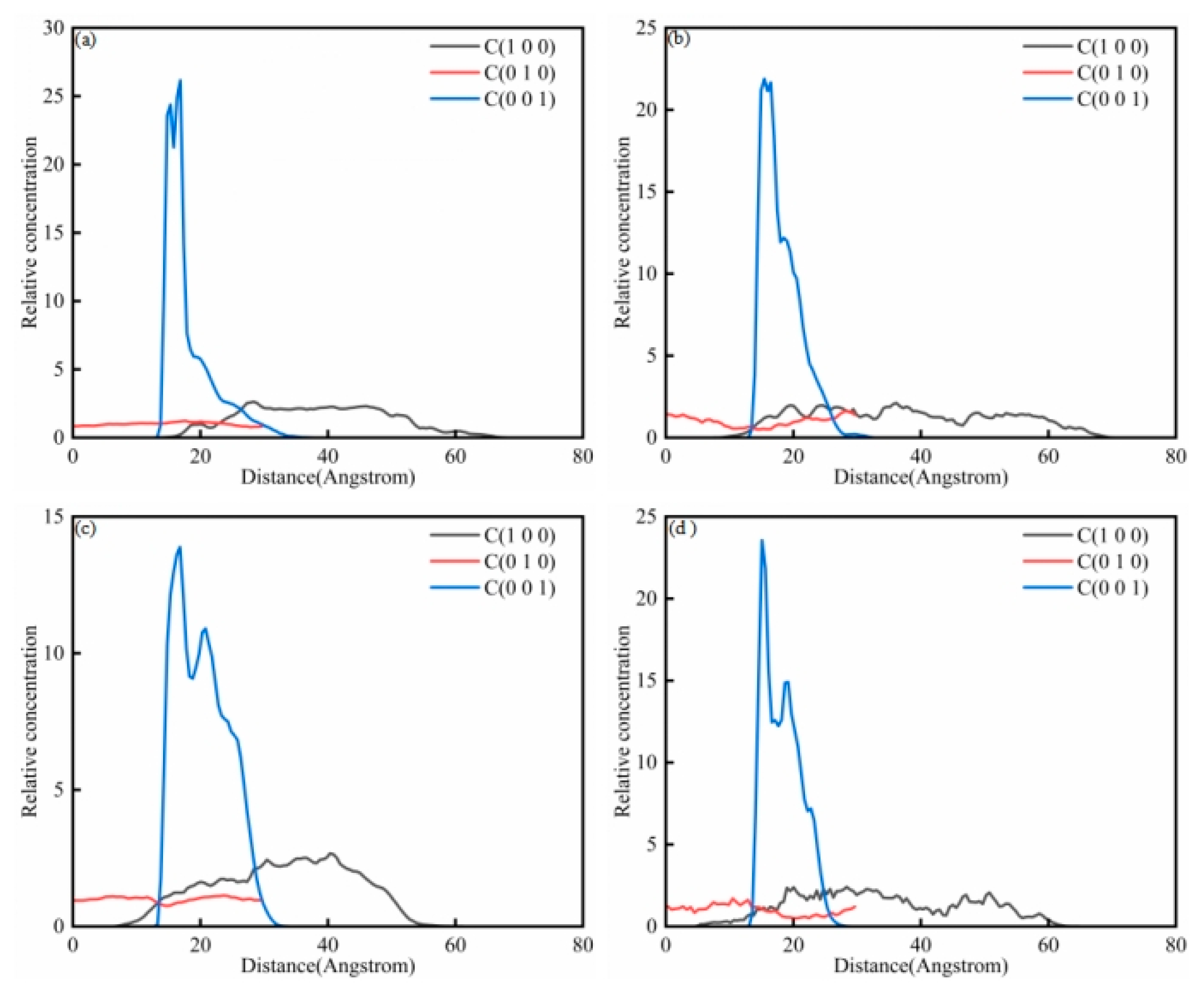

Figure 12a shows the analysis of saturated concentration in the saturated component–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration for different crystal planes. In the C001 crystal plane, the overall trend is for an initial rise first and then a fall; the maximum value occurs at 17. There was an overall upward trend from 13 to 17, followed by a downward trend between 17 and 38. In the C100 crystal plane, there is an upward trend from 12 to 29, a gentle trend from 29 to 36, and a downward trend between 36 and 68. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 30 shows a flat trend. From 14 to 23, the concentration of crystal plane C010 is greater than that of crystal plane C100 and less than that of crystal plane C001.

Figure 12b shows the analysis of aromatic concentration in the aromatic component–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C001 crystal plane, there is an initial rise and then a fall, with a maximum value at 15. There is an upward trend from 13 to 15, and then a downward trend from 15 to 33. In the C100 crystal plane, there is an upward trend from 7 to 20 and a general trend of fluctuating decline from 20 to 70. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 30 showed a trend of first decreasing and then rising. From 14 to 26, the concentration of crystal plane C100 is greater than that of crystal plane C010 and less than that of C001.

Figure 12c shows the analysis of colloidal concentration in the colloid–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C001 crystal plane, the overall trend is an initial rise and then a fall, with a maximum value at 16. The results showed an upward trend from 13 to 16, followed by an overall downward trend from 16 to 34. In the C100 crystal plane, there is an upward trend from 6 to 41 and a downward trend from 41 to 61. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 12 showed a gentle trend, 12 to 24 showed a downward trend and then rose, and 24 to 30 showed a downward trend. From 13 to 28, the concentration of crystal plane C100 is greater than that of crystal plane C010 and less than that of crystal plane C001.

Figure 12d shows the analysis of asphaltene concentration in the asphaltene–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C001 crystal plane, the overall trend is an initial rise and then a fall, with a maximum value at 15. There was an upward trend from 13 to 15, followed by an overall downward trend from 15 to 29. In the C100 crystal plane, it shows an upward trend from 0 to 20, a downward trend from 20 to 44, and an overall upward trend and then a downward trend from 44 to 65. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 13 showed a gentle trend and 13 to 30 showed a trend of first decreasing and then rising. From 15 to 25, the concentration of crystal plane C100 is greater than that of crystal plane C010 and less than that crystal plane C001.

Figure 13a shows the concentration analysis diagram for sodium laureth sulfate in the saturated fraction–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C100 crystal plane, the overall trend shows an initial decline, flowed by a rise, and then a second decline before rising again. From 0 to 15, there is a downward trend; 15 to 45 shows an overall upward trend; and 45 to 73 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 11 showed an upward trend and 11 to 30 showed a downward trend. In the C001 crystal plane, 13 to 21 showed an upward trend, 21 to 42 showed a downward trend and then rose, and 42 to 66 showed a downward trend. From 16 to 30, the concentration of crystal plane C010 is greater than that of C100 and less than that of C001.

Figure 13b shows the concentration analysis of sodium laureth sulfate in the aromatic component–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C100 crystal plane, the overall trend is to increase first, then decrease, and finally rise. From 0 to 23, there is an overall upward trend; 23 to 50 shows a downward trend; and 50 to 73 shows an upward trend. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 30 showed a trend of rising first and then decreasing. In the C001 crystal plane, 13 to 24 showed an upward trend, 24 to 43 showed a downward trend and then rose, and 43 to 71 showed a downward trend. From 16 to 30, the concentration of crystal plane C100 is greater than that of C010 and less than that of C001.

Figure 13c shows the concentration analysis of sodium laureth sulfate in the colloid–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C100 crystal plane, there is an overall trend of an initial decline, followed by a rise, and finally another decline. From 0 to 40, there is an overall downward trend; 40 to 55 shows an upward trend; and 55 to 73 shows a downward trend. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 30 showed a trend of rising first and then decreasing. In the C001 crystal plane, 13 to 30 showed an upward trend and 30 to 69 showed an overall downward trend. From 15 to 30, the concentration of C010 in the crystal plane is greater than that of C100 and less than that of C001.

Figure 13d shows the concentration analysis diagram for sodium laureth sulfate in the asphaltene–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C100 crystal plane, there is an overall decrease and then an increase. From 0 to 45, there is an overall downward trend, and from 45 to 73, it rises first and then decreases. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 15 showed a trend of first rising and then falling and 15 to 30 showed a gentle trend. In the C001 crystal plane, 13 to 25 showed an upward trend, 25 to 43 showed a downward trend and then rose, and 43 to 65 showed a downward trend. From 16 to 26, the concentration of crystal plane C100 is greater than that of C010 and less than that of C001.

Figure 14a shows the diffusion conformation diagram of saturated fractions in sodium laureth sulfate. The diffusion effect of saturated molecules gradually increases as the simulation progresses. When the simulation begins, the saturated molecules clump together, but as the simulation progresses, the saturated molecules diffuse in the solvent. When 3200 ps is reached, the saturation partial diffusion is stable. When 4000 ps is reached, there is little difference in saturated molecular diffusion.

Figure 14b shows the diffusion conformation of aromatic molecules in sodium laureth sulfate. The diffusion effect of aromatic molecules gradually increases with the simulation time. When the simulation begins, the aromatic molecules clump together, but as the simulation progresses, the aromatic molecules diffuse in the solvent. When 2400 ps is reached, the aromatic diffusion is stable. When 4000 ps is reached, there is little difference in aromatic molecular diffusion.

Figure 14c shows the conformation diagram of the diffusion of glia in sodium laureth sulfate. The diffusion effect gradually increases with the simulation time. When the simulation begins, the glial molecules clump together, but as the simulation progresses, the glial molecules diffuse in the solvent. When 2400 ps is reached, the colloidal diffusion is stable. When 4000 ps it reaches, there is little difference in the diffusion of glial molecules.

Figure 14d shows the diffusion conformation diagram of asphaltene in sodium laureth sulfate. The asphaltene diffusion effect gradually increases with the simulation time. When the simulation begins, the asphaltene molecules clump together, but as the simulation progresses, the asphaltene molecules diffuse in the solvent. When 2400 ps is reached, asphaltene diffusion is stable. When 4000 ps is reached, there is little difference in the diffusion of asphaltene molecules.

Figure S1 shows the energy balance diagram of the SARA component and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the energy fluctuates in the first 50 ps and the energy is stable after 50 ps. When the simulation time is the same, the kinetic energy is the largest, followed by the total energy, the non-bond energy, and the potential energy. The results indicate that the simulation energy system reached equilibrium when the simulation system reached 2500 ps.

Figure S2 shows the temperature equilibrium diagram of the saturated component and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the temperature fluctuation range is from 291 K to 307 K and the overall temperature is around 298 K, indicating that the simulation has reached the temperature equilibrium state and the data is valid. The results indicated that the simulation system reached equilibrium when the simulation time reached 2500 ps.

Figure S3a shows the MSD diffusion diagram of the saturated component and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the diffusion coefficient of the saturated part is greater than that of sodium laureth sulfate. The diffusion of the saturation fraction increases with simulation time. The MSD value gradually increases when the simulation time is close to 2300 ps. The MSD coefficient fluctuated up and down. The MSD value of sodium laureth sulfate increases gently with the simulation time. This is because the simulation is unstable over short time frames, meaning the interaction between saturated content and sodium laureth sulfate does not reach a stable value, and instead gradually increases.

Figure S3b is an MSD diffusion diagram of aromatic components and the sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the diffusion coefficient of sodium laureth sulfate is greater than that of the aromatic. The diffusion of aromatic content shows that the MSD value gradually increases with the increase in simulation time, and the MSD coefficient increases rapidly when the simulation time is close to 2300 ps. The MSD value of sodium laureth sulfate increased steadily with the simulation time, increasing rapidly when the simulation time was close to 2400 ps. This is because the simulation is unstable in short time frames, meaning the interaction between aromatic content and sodium laureth sulfate does not reach a stable value, and instead gradually increases.

Figure S3c is an MSD diffusion diagram of the colloidal and sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the diffusion coefficient of sodium laureth sulfate is greater than that of glia. When the simulation time is close to 1500 ps, the MSD coefficient first rises rapidly, then slowly, and finally rises rapidly again. The MSD value of sodium laureth sulfate rising gently with increasing simulation time, and the MSD coefficient rises rapidly when the simulation time is close to 2300 ps. At the same time, the interaction between glia and sodium laureth sulfate did not reach a stable value, so it gradually increased.

Figure S3d is an MSD diffusion diagram of asphaltene and sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that the diffusion coefficient of sodium laureth sulfate is greater than that of asphaltene. The diffusion of asphaltene shows that the MSD value increases gradually with the increase in simulation time, and the MSD coefficient increases rapidly when the simulation time is close to 2200 ps. The MSD value of sodium laureth sulfate rose steadily with the simulation time, increasing rapidly when the simulation time approached 2200 ps. This is because the simulation is unstable in short time frames, meaning the interaction between asphaltene and sodium laureth sulfate does not reach a stable value, and instead gradually increases.

Figure S4a shows the RDF plot of the saturated component and the sodium laureth sulfate system. For the saturation fraction, there are three main peaks, with peak positions of 1.1 A, 1.5 A, and 2.2 A, respectively. For sodium laureth sulfate, a major peak position occurs at 1.1 A. The results of the radial distribution function show that the relative positions of the interactions between the saturated atoms are higher than those between sodium laureth sulfate. The total blue curve, the diagram of saturated component and sodium laureate lysozyme sulfate, shows that there is no obvious peak between the saturated molecule and the sodium laureate lysozyme sulfate molecule, and the peak position reaches equilibrium after 6 A.

Figure S4b is the RDF diagram of the aromatic component and sodium laureth sulfate system. For aromatic components, there are four main peaks, with peak positions of 1.1 A, 1.4 A, 2.2 A, and 2.5 A, respectively. For sodium laureth sulfate, a major peak position occurs at 1.1 A. The results of the radial distribution function show that the relative position of the interaction between the aromatic atoms is higher than that between sodium laureth sulfate. The total blue curve, the plot of the aromatic fraction and sodium laureth sulfate, shows that there is no obvious peak between the aromatic molecule and the sodium laureth sulfate molecule as a whole, and the peak position reaches equilibrium after 6 A.

Figure S4c is an RDF diagram of the colloid and sodium laureth sulfate system. For glia, there are three main peaks, with peak positions of 1.1 A, 1.5 A, and 2.2 A, respectively. For sodium laureth sulfate, a major peak position occurs at 1.1 A. The results of the radial distribution function show that the relative position of the interaction between the colloidal atoms is higher than that between sodium laureth sulfate. The total blue curve, the graph of the colloid and sodium laureth sulfate, shows that there is no obvious peak between the colloid and sodium laureth sulfate molecules as a whole, and the peak position reaches equilibrium after 6 A.

Figure S4d is the RDF diagram of asphaltene and sodium laureth sulfate system. For asphaltene, there are four main peaks, with peak positions of 1.1 A, 1.4 A, 2.2 A, and 2.4 A, respectively. For sodium laureth sulfate, a major peak position occurs at 1.1 A. The results of the radial distribution function show that the relative positions of the interactions between asphaltene atoms are higher than those between sodium laureth sulfate. The overall blue curve, the plot of asphaltene and sodium laureth sulfate, shows that there is no obvious peak between the asphaltene molecule and the sodium laureth sulfate molecule as a whole, and the peak position reaches equilibrium after 6 A.

Figure S5a shows the analysis of saturated concentration in the saturated component–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C001 crystal plane, the concentration initially decreases and then rises before finally falling and rising again. The maximum value occurs at 35. It shows a downward trend from 0 to 10, followed by an upward trend from 10 to 19, a downward trend from 19 to 23, and finally an upward trend from 23 to 35. In the C100 crystal plane, the trend rises and then decreases from 0 to 5, rises and then decreases from 5 to 18, rises from 18 to 24, and decreases from 24 to 35. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 5 shows an upward trend, 5 to 16 shows a downward trend, 16 to 25 shows a trend of first rising and then falling, and 25 to 35 shows a trend of first rising and then falling. From 6 to 11, the concentration of crystal plane C100 is greater than that of crystal plane C001 and less than that of crystal plane C010. From 21 to 29, the concentration of crystal plane C001 is greater than that of crystal plane C010 and less than that of C100.

Figure S5b shows the analysis of aromatic concentration in the aromatic component–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C001 crystal plane, the concentration first decreases and then rises, before finally falling and rising again. The maximum value occurs at 1. This crystal plane shows a downward trend from 0 to 8, rises and then falls from 8 to 22, rises from 22 to 30, and finally falls before rising again from 30 to 36. In the C100 crystal plane, it first rises and then decreases from 0 to 10, rises and then decreases from 10 to 15, rises from 15 to 26, and decreases and then rises from 26 to 36. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 6 shows an upward trend, 6 to 14 shows a downward trend, 14 to 16 shows a rapid upward trend, and 16 to 36 shows a general downward trend. From 15 to 19, the concentration of crystal plane C001 was greater than that of crystal plane C100 and less than that of C010. From 19 to 24, the concentration of crystal plane C100 was greater than that of crystal plane C001 and less than that crystal plane C010.

Figure S5c shows the analysis of colloidal concentration in the colloid–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C001 crystal plane, the overall trend is an initial fall, then a rise, then a fall, and finally a rises and then another fall, with a maximum value at 9. It shows a downward trend from 0 to 4, followed by a rapid upward trend from 4 to 9, a flat trend from 9 to 15, a downward trend from 15 to 24, and finally a trend of rising and then falling from 24 to 36. In the C100 crystal plane, there is a trend of first decreasing and then rising rapidly from 0 to 8, a general downward trend from 8 to 25, and a trend of first rising and then decreasing from 25 to 36. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 5 shows a downward trend, 5 to 9 shows a gentle trend, 9 to 15 shows a trend of first rising and then falling, 15 to 25 shows a trend of first rising and then falling, 25 to 33 shows a trend of first rising and then falling, and finally 33 to 36 shows an upward trend. From 4 to 9, the concentration of crystal plane C001 is greater than that of crystal plane C010 and less than that of crystal plane C100. From 21 to 27, the concentration of crystal plane C100 was greater than that of crystal plane C001 and less than that of crystal plane C010.

Figure S5d shows the analysis of asphaltene concentration in the asphaltene–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C001 crystal plane, the curve first decreases, then rises, then falls, and finally rises, with a maximum value at 34. It shows a downward trend from 0 to 13, followed by an upward trend and then a downward trend from 13 to 23, an overall upward trend from 23 to 32, and finally a flat trend from 32 to 37. In the C100 crystal plane, there is a downward trend from 0 to 6, an upward trend from 6 to 14, a downward trend and then an upward trend from 14 to 23, and a downward trend and then an upward trend from 23 to 37. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 13 shows a trend of rising first and then decreasing, 13 to 33 shows an overall upward trend, and 33 to 37 shows a downward trend. From 10 to 27, the concentration of crystal plane C010 was greater than that of crystal plane C001 and less than that of crystal plane C100.

Figure S6a shows the concentration analysis diagram of sodium laureth sulfate in the saturated component–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C100 crystal plane, the overall trend exhibits an initial rise, then a decrease, then a rise, and finally a decrease. From 0 to 6, there is an upward trend; 6 to 11 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend; 11 to 15 shows a downward trend; 15 to 26 shows a downward trend; and 26 to 35 shows a trend of first rising and then decreasing. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 5 shows a downward trend, 5 to 15 shows an upward trend, 15 to 23 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend, 23 to 28 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend, and 28 to 35 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend. In the C001 crystal plane, 0 to 14 shows an upward trend, 14 to 19 shows a rapid downward trend, 19 to 29 shows an overall upward trend, and 29 to 35 shows a downward trend. From 7 to 12, the concentration of crystal plane C100 is greater than that of C010 and less than that of C001. At 20 to 24, the concentration of C001 in the crystal plane is greater than that of C100 and less than that of C010.

Figure S6b shows the concentration analysis of sodium laureth sulfate in the aromatic component–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C100 crystal plane, the overall trend is to first increase, then decrease, and finally rise and then decrease. From 0 to 16, there is an upward trend; 16 to 27 shows a downward trend; and 27 to 33 shows a trend of rising first and then decreasing. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 7 shows a downward trend, 7 to 14 shows an upward trend, 14 to 20 shows a downward trend, 20 to 29 shows an upward trend, and 29 to 33 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend. In the C001 crystal plane, 0 to 24 shows an overall upward trend and 24 to 33 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend. From 14 to 19, the concentration of crystal plane C001 is greater than that of C010 and less than that of C100. From 23 to 25, the crystal plane C100 concentration is greater than that of C010 and less than that of C001.

Figure S6c shows the concentration analysis of sodium laureth sulfate in the colloid–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C100 crystal plane, the overall trend is for an initial decline, then a rise, and finally a decline. From 0 to 7, there is a downward trend; 7 to 25 shows an overall upward trend; and 25 to 37 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 8 shows an upward trend, 8 to 18 shows a downward trend, 18 to 25 shows an upward trend, 25 to 32 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend, and 32 to 37 shows a downward trend and then an upward trend. In the C001 crystal plane, 0 to 5 shows an upward trend, 5 to 10 shows a rapid downward trend, 10 to 16 shows a flat trend, 16 to 25 shows a rapid upward trend, 25 to 35 shows a downward trend, and 35 to 37 shows an upward trend. From 6 to 9, the concentration of the crystal plane C001 is greater than that of C100 and less than that of C010. From 22 to 31, the crystal plane C100 concentration is greater than that of C010 and less than that of C001.

Figure S6d shows the concentration analysis diagram of sodium laureth sulfate in the asphaltene–sodium laureth sulfate system. It can be seen from the figure that there are differences in concentration on different crystal planes. In the C100 crystal plane, the overall trend is an initial decrease and then a rise. From 0 to 14, there is a downward trend; 14 to 35 is an upward trend; and 35 to 37 is a downward trend. In the C010 crystal plane, 0 to 4 shows a downward trend, 4 to 16 shows an upward trend, 16 to 34 shows a downward trend, and 34 to 37 shows an upward trend. In the C001 crystal plane, 0 to 7 shows a trend of rising first and then falling, 7 to 19 shows an upward trend and then a fall, 19 to 23 shows an upward trend, and 23 to 37 shows an overall downward trend. From 9 to 21, the concentration of the crystal plane C001 is greater than that of C100 and less than that of C010.

Figure S7a shows the diffusion conformation diagram of the saturated fractions in sodium laureth sulfate. The diffusion effect of saturated molecules gradually increases as the simulation progresses. When the simulation begins, the saturated molecules clump together, but as the simulation progresses, the saturated molecules diffuse in the solvent. When 1000 ps is reached, the saturation diffusion is stable. When 2500 ps is reached, there is little difference in saturated molecular diffusion.

Figure S7b shows the diffusion conformation of aromatic molecules in sodium laureth sulfate. The diffusion effect of aromatic molecules gradually increases with the simulation time. When the simulation begins, the aromatic molecules clump together, but as the simulation progresses, the aromatic molecules diffuse in the solvent. When 1000 ps is reached, the aromatic diffusion is stable. When 2500 ps is reached, there is little difference in aromatic molecular diffusion.

Figure S7c shows the conformation diagram of the diffusion of glia in sodium laureth sulfate. The diffusion effect gradually increases with the simulation time. When the simulation begins, the glial molecules clump together, but as the simulation progresses, the glial molecules diffuse in the solvent. When 1000 ps is reached, colloidal diffusion is stable. When 2500 ps is reached, there is little difference in the diffusion of colloidal molecules.

Figure S7d shows the diffusion conformation diagram of asphaltene in sodium laureth sulfate. The asphaltene diffusion effect gradually increases with the simulation time. When the simulation begins, the asphaltene molecules clump together, but as the simulation progresses, the asphaltene molecules diffuse in the solvent. When 1000 ps is reached, asphaltene diffusion is stable. When 2500 ps is reached, there is little difference in asphaltene molecular diffusion.