Combatting Antibiotic Resistance Together: How Can We Enlist the Help of Industry?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Background: Current Responses Are Insufficient

3. Methods

- Marketing and promotion

- Perverse incentives

- Supply initiation and continuity

- Surveillance—data collection and disclosure (sales and emerging resistance)

- Formulary controls

- Post-market (clinical) data generation

- Environment (supply chain pollution)

- Non-human use

- Third-party control of the product

- Availability challenges

- Sub-optimal clinical use

- Supply chain challenges and risks

- Off-label use

- Substandard/spurious/falsely-labelled/falsified/counterfeit medical products (SSFFC)

- Market authorization and labelling

- Pricing and reimbursement

- Donations

- ‘Clear opportunities’ for action: In optimizing clinically appropriate use. Between the current situation (where we are now) and the desired situation (where we would like to be).

- No likely lego-regulatory response: Anticipated to address the issue in the next decade. The likely absence of a legislative or other system-wide mechanisms increases the imperative to tie the issue to a specific R&D incentive.

- Reasonable industry influence: Over the issue given their role in the antibiotic lifecycle (product development, production, and global sales and distribution). For each domain, do developers have ‘reasonable’ responsibility or influence? To what degree could a condition be considered reasonable and practical bearing in mind the comparative advantage and cost relative to other stakeholders who could potentially take on a greater role in sustainable use in this space.

- Realistic to address early in product development: Are the risks presented by the identified domain largely general to the high unmet need antibiotic class and the general pharmaceutical business model? Are they conceivable and hence could they be, at least, mitigated through an early-defined condition that would be potentially blunt and non-specific but would maximize early developer certainty.

4. Findings and Discussion

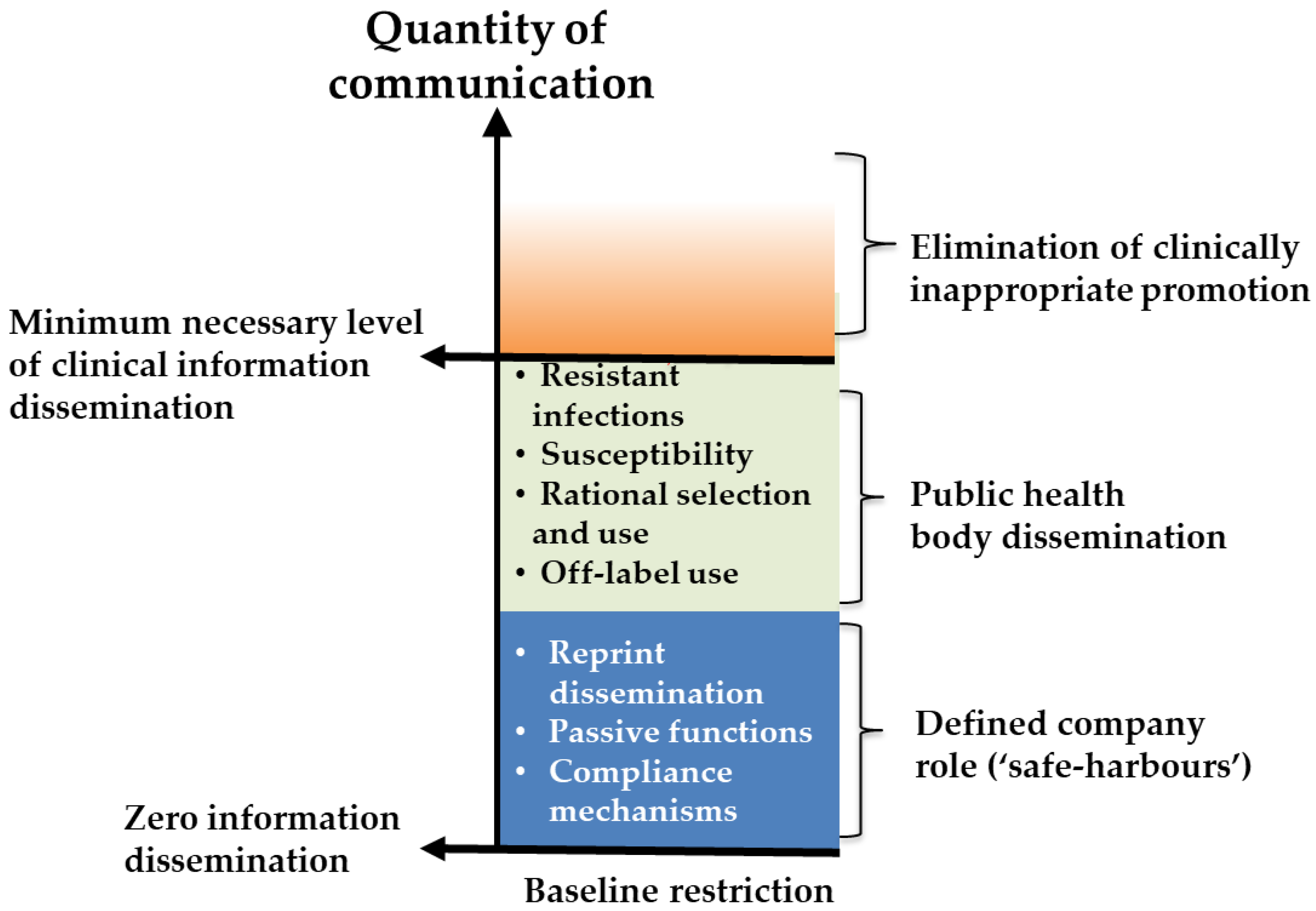

5. Domain 1—Marketing and Promotion

5.1. Background and Justification for Inclusion in Developer Conditions

5.2. Considerations for Condition Design

- To be supported by an enhanced role of public health bodies in informing practitioners etc.

- A globally accessible, anonymous, whistleblower facility (supported by a policy of non-retaliation and by qui tam style financial incentives).

6. Domain 2—Perverse Incentives

6.1. Background and Justification for Inclusion as a Developer Condition

6.2. Consideration for Condition Design

7. Domain 3—Supply Initiation and Continuity

7.1. Background and Justification for Inclusion as a Developer Condition

- Minimum national safeguards: the risk to waning product efficacy from being used in countries without minimum product-specific SU safeguards in place (risk of oversupply where there is an insufficient ability to provide the product in an appropriate manner).

- Supply continuity: the risk to appropriate stewardship from disruptions in the supply of the novel product (risk of undersupply when the product is in routine use).

7.2. Supply Initiation and SU-Safeguards

7.3. Supply Continuity

- Lack the ability to distribute/prescribe appropriately (unless this is guaranteed by a third-party) and/or

- Do not have an effective national supply control and stewardship plan in place.

8. Domain 4—Surveillance—Data Collection and Disclosure (Sales Data and Evidence of Emerging Resistance)

8.1. Background and Justification for Inclusion in Developer Condition

8.2. Considerations for Condition Design

9. Domain 5—Formulary Controls

9.1. Background and Justification for Inclusion in Developer Condition

9.2. Considerations for Obligation Design

10. Domain 6—Post-Market (Clinical) Data Generation

10.1. Background and Justification for Inclusion in Developer

10.2. Considerations for Condition Design

11. Domain 7—Environment (Supply Chain Pollution)

11.1. Background and Rationale for Condition

11.2. Contractual Condition

12. Domain 8—Non-Human Use

12.1. Background and Justification for Inclusion in Developer Condition

12.2. Considerations for Condition Design

13. Domain 9—Third-Party Control of Product

13.1. Background and Justification for Inclusion in Developer Condition

13.2. Considerations for Condition Design

14. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mendelson, M.; Balasegaram, M. Antibiotic Resistance Has a Language Problem. Nature 2017, 545, 23–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Kingdom AMR Review. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations. 2016. Available online: https://amr-review.org/sites/ default/files/160525_Final%20paper_ with%20cover.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- Daniel, G.W.; McClellan, M.B. Value-Based Strategies for Encouraging New Development of Antimicrobial Drugs. Available online: https://healthpolicy.duke.edu/sites/default/files/atoms/files/value-based_strategies_for_encouraging_new_development_of_antimicrobial_drugs.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2017).

- Innovative Medicines Initiative (IMI). COMBACTE. Available online: https://www.combacte.com/about/ (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Combatting Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria. CARB-X. Available online: https://carb-x.org/about/overview/ (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Global Antibiotic Research and Developement Partnership (GARDP). Available online: https://www.gardp.org (accessed on 11 December 2018).

- Access to Medicines Foundation. Antimicrobial Resistance Benchmark. 2018. Available online: https://amrbenchmark.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Antimicrobial-Resistance-Benchmark-2018.pdf (accessed on 30 November 2018).

- IFPMA. Declaration by the Pharmaceutical, Biotechnology and Diagnostics Industries on Combating Antimicrobial Resistance. 2016. Available online: https://www.ifpma.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/Industry_Declaration_on_Combating_Antimicrobial_Resistance_UPDATED-SIGNATORIES_MAY_2016.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- IFPMA. Industry Roadmap for Progress on Combating Antimicrobial Resistance. 2016. Available online: https://www.ifpma.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/Roadmap-for-Progress-on-AMR-FINAL.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2016).

- AMR Industry Alliance. Tracking Progress to Address AMR. 2018. Available online: https://www.amrindustryalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/AMR_Industry_Alliance_Progress_Report_January2018.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2018).

- Francer, J.; Izquierdo, J.Z. Ethical pharmaceutical promotion and communications worldwide: Codes and regulations. Philos. Ethics Hum. Med. 2014, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. World Medicines Situation. 2004. Available online: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/pdf/s6160e/s6160e.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2017).

- World Health Assembly. Progress in the Rational Use of Medicines (WHA60.16). 2007. Available online: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s21451en/s21451en.pdf (accessed on 17 January 2017).

- The Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). Code on Interactions with Healthcare Professionals. Available online: http://phrma-docs.phrma.org/sites/default/files/pdf/phrma_marketing_code_2008.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2017).

- Med Ed Web Solutions. 8 Medical Marketing Ideas for Promoting Continued Medical Education (CME) Events’. Available online: https://www.mededwebs.com/blog/5-medical-marketing-strategy-ideas-for-promoting-continued-medical-education-cme (accessed on 23 January 2017).

- Golestaneh, L.; Cowan, E. Hidden Conflicts of Interest in Continuing Medical Education. Lancet 2017, 390, 2128–2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Promotion of FDA-Regulated Medical Products Using the Internet and Social Media Tools. Part 15 Public Hearing. 2009. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/CDER/ucm184250.htm (accessed on 23 January 2017).

- Williams, A.; London School of Economics. Working Paper: Economic Theory of Self-Regulation. 2004. Available online: http://anthonydwilliams.com/wp-content/uploads/2006/08/An_Economic_Theory_of_Self-Regulation.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2016).

- Kesselheim, A.S.; Mello, M.M.; Studdert, D.M. Strategies and Practices in Off-Label Marketing of Pharmaceuticals: A Retrospective Analysis of Whistleblower Complaints. PLoS Med. 2011, 8, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesselheim, A.S.; Studdert, D.M.; Mello, M.M. ‘Whistle-Blowers’ Experiences in Fraud Litigation against Pharmaceutical Companies’. NEJM 2010, 362, 1832–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Action International. A New (and Improved) Model to Regulate Pharmaceutical Promotion. Available online: http://haiweb.org/a-new-and-improved-model-to-regulate-pharmaceutical-promotion/ (accessed on 2 February 2017).

- Trotter, D.M.; Bateman, B.; Avorn, J. Educational Outreach to Opioid Prescribers: The Case for Academic Detailing. Pain Phys. 2017, 20, S147–S151. [Google Scholar]

- Mello, M.M.; Studdert, D.M.; Brennan, T.A. Shifting terrain in the regulation of off-label promotion of pharmaceuticals. NEJM 2009, 360, 1557–1566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Currie, J.; Lin, W.; Meng, J. Addressing Antibiotic Abuse in China: An Experimental Audit Study. J. Dev. Econ. 2014, 110, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Good Governance for Medicines Programme. Available online: https://www.who.int/medicines/areas/policy/goodgovernance/en/ (accessed on 21 April 2017).

- World Health Organization. Evaluation of the Good Governance for Medicines Programme (2004–2012). Brief Summary of Findings. 2013. Available online: http://www.who.int/medicines/areas/policy/goodgovernance/1426EMP_GoodGovernanceMedicinesreport.pdf?ua=1 (accessed on 21 April 2017).

- Paul Weiss. FCPA Enforcement and Anti-Corruption Developments: 2016 Year in Review. 2016. Available online: https://www.paulweiss.com/media/3897243/19jan17_fcpa_year_end.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2017).

- Access to Medicines Foundation. Access to Medicines Index 2016. Available online: https://accesstomedicineindex.org/media/atmi/Access-to-Medicine-Index-2016.pdf (accessed on 24 March 2017).

- World Health Organization. The Green Light Committee Initiative: Frequently Asked Questions. Available online: http://www.who.int/tb/challenges/mdr/greenlightcommittee/glc_faq.pdf (accessed on 12 July 2016).

- Iyengar, S.; Hedman, L.; Forte, G.; Hill, S. Medicine Shortages: A Commentary on Causes and Mitigation Strategies’. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Medicines Shortages: Global Approaches to Addressing Shortages of Essential Medicines in Health Systems’. WHO Drug Inf. 2016, 30, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Quadri, F.; Mazer-Amirshahi, M.; Fox, E.R.; Hawley, K.L.; Pines, J.M.; Zocchi, M.S.; May, L. Antibacterial Drug Shortages from 2001 to 2013: Implications for Clinical Practice. Clin Infect Dis. 2015, 60, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 69th World Health Assembly. Addressing the Global Shortage of Medicines and Vaccines. 2016. Available online: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s22423en/s22423en.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Huq, F.; Pawar, K.S.; Rogers, H. Supply Chain Configuration Conundrum: How Does the Pharmaceutical Industry Mitigate Disturbance Factors. Prod. Plan. Control 2016, 27, 1206–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy for Containment of Antimicrobial Resistance. 2001. Available online: http://www.who.int/drugresistance/WHO_Global_Strategy_English.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2017).

- Critchley, I.A.; Karlowsky, J.A. Optimal Use of Antibiotic Resistance Surveillance Systems. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency. Guideline on Good Pharmacovigilance Practices (GVP). 2013. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/scientific-guideline/guideline-good-pharmacovigilance-practices-gvp-module-vii-periodic-safety-update-report_en.pdf (accessed on 9 May 2017).

- European Commission. Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2016/161. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/counterf_par_trade/planning.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2017).

- European Commission. Implementation Measures by the Commission in the Context of Directive 2011/62/EU—Overview and State of Play. 2015. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/files/eudralex/vol-1/reg_2016_161/reg_2016_161_en.pdf (accessed on 17 May 2017).

- FDA. Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA). 2013. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/DrugIntegrityandSupplyChainSecurity/DrugSupplyChainSecurityAct/ (accessed on 22 May 2017).

- Garattini, S.; Bertele, V.; Bertolini, G. A failed attempt at collaboration. BMJ 2013, 347, 5354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monnet, D.L. Toward multinational antimicrobial resistance surveillance systems in Europe. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2000, 15, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ECDC. Surveillance and Disease Data for Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: http://ecdc.europa.eu/en/healthtopics/antimicrobial-resistance-and-consumption/antimicrobial_resistance/EARS-Net/Pages/EARS-Net.aspx (accessed on 21 April 2017).

- European Medicines Agency. ‘Reporting Requirements of Individual Case Safety Reports (ICSRs) Applicable to Marketing Authorisation Holders during the Interim Period’. Available online: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Regulatory_and_procedural_guideline/2012/05/WC500127657.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2017).

- Hogerzeil, H.V. The Concept of Essential Medicines: Lessons for Rich Countries. BMJ 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Promoting Rational Use of Medicines: Core Components. 2002. Available online: http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/policyperspectives/ppm05en.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2016).

- Huskamp, H.A.; Keating, N.L. The New Medicare Drug Benefit: Formularies and Their Potential Effects on Access to Medications. J. Gen. Int. Med. 2005, 20, 662–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Updates Essential Medicines List with New Advice on Use of Antibiotics, and Adds Medicines for Hepatitis C, HIV, Tuberculosis and Cancer. 2017. Available online: http://www.who.int/en/news-room/detail/06-06-2017-who-updates-essential-medicines-list-with-new-advice-on-use-of-antibiotics-and-adds-medicines-for-hepatitis-c-hiv-tuberculosis-and-cancer#.WTcmynk8mj4.email (accessed on 29 June 2017).

- World Health Organization. Promoting Rational Prescribing. 2012. Available online: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s19606en/s19606en.pdf (accessed on 17 November 2016).

- NLEM. National List of Essential Medicines of India. 2011. Available online: http://www.cdsco.nic.in/writereaddata/National%20List%20of%20Essential%20Medicine-%20final%20copy.pdf (accessed on 22 November 2016).

- Magrini, N.; World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. Personal communication, 2016.

- Magrini, N. As Cited in Branswell Blog, H. Health Officials Set to Release a List of Drugs Everyone on Earth Should Be Able to Access. 2017. Available online: https://www.statnews.com/2017/06/05/essential-medicines-list-who/ (accessed on 23 June 2017).

- European Medicines Agency. Guidance on the Format of the Risk Management Plan (RMP) in the EU—In Integrated Format. 2017. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/documents/regulatory-procedural-guideline/guidance-format-risk-management-plan-rmp-eu-integrated-format-rev-2_en.pdf (accessed on 23 November 2016).

- Office for Health Economics. The Precautionary Principle in Healthcare. Available online: https://www.ohe.org/news/precautionary-principle-healthcare (accessed on 17 October 2016).

- Cox, E.; Laessig, K. FDA Approval of Bedaquiline—The Benefit–Risk Balance for Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis. NEJM 2014, 371, 689–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DNDi. Selecting for Success in the Field: The Target Product Profile. Available online: https://www.dndi.org/diseases-projects/target-product-profiles/ (accessed on 2 December 2016).

- World Health Organization. WHO’s Preferred Product Characteristics (PPCs) and Target Product Profiles (TPPs). Available online: http://www.who.int/immunization/research/ppc-tpp/en/ (accessed on 7 December 2016).

- AMR Industry Alliance. Common Antibiotic Manufacturing Framework. 2018. Available online: https://www.amrindustryalliance.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/AMR_Industry_Alliance_Manufacturing_Framework.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2018).

- AMR Industry Alliance. Pharmaceuticals in the Environment. 2018. Available online: https://www.amrindustryalliance.org/mediaroom/pharmaceuticals-in-the-environment/ (accessed on 16 October 2018).

- World Health Organization. Highest Priority Critically Important Antimicrobials. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/foodsafety/cia/en/ (accessed on 13 June 2017).

- World Organization for Animal Health. OIE List of Antimicrobial Agents of Veterinary Importance. 2015. Available online: http://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Our_scientific_expertise/docs/pdf/Eng_OIE_List_antimicrobials_May2015.pdf (accessed on 11 June 2017).

- World Health Organization Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance and of Antimicrobial Resistance (AGISAR). Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine 4th Revision. 2013. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/251715/9789241511469-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 6 December 2016).

- FAO. Code of Practice to Minimize and Contain Antimicrobial Resistance. 2005. Available online: www.fao.org/input/download/standards/10213/CXP_061e.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2017).

- European Medicines Agency. Recommendation on the Evaluation of the Benefit-Risk Balance of Veterinary Medicinal Products. 2007. Available online: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Other/2009/10/WC500005264.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2016).

- European Medicines Agency. Use of Glycylcyclines in Animals in the European Union: Development of Resistance and Possible Impact on Human and Animal Health. 2013. Available online: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2013/07/WC500146814.pdf (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- Food and Drug Administration. New Animal Drugs; Cephalosporin Drugs; Extralabel Animal Drug Use; Order of Prohibition. 2012. Available online: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/01/06/2012-35/new-animal-drugs-cephalosporin-drugs-extralabel-animal-drug-use-order-of-prohibition (accessed on 19 December 2016).

- European Medicines Agency. Updated Advice on the Use of Colistin Products in Animals within the European Union: Development of Resistance and Possible Impact on Human and Animal Health. 2016. Available online: http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2016/07/WC500211080.pdf (accessed on 20 December 2016).

- Diaz, F. Antimicrobial Use in Animals: Analysis of the OIE Survey on Monitoring of the Quantities of Antimicrobial Agents Used in Animals. 2013. Available online: http://www.oie.int/eng/A_AMR2013/Presentations/S2_4_FrançoisDiaz.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2016).

- Vanderhaeghen, W.; Dewulf, J. Antimicrobial Use and Resistance in Animals and Human Beings. Lancet Planet. Health 2017, 1, e307–e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toutain, P.L.; Ferran, A.A.; Bousquet-Melou, A.; Pelligand, L.; Lees, P. Veterinary Medicine Needs New Green Antimicrobial Drugs. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 3, 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Astellas. Astellas Enters into Partnership with Optimer on Life-Saving Antibiotic Fidaxomicin. 2011. Available online: http://www.astellas.de/presse/artikel.html?press_id=138 (accessed on 22 December 2016).

| Possible Regulatory Action | Examples of Use |

|---|---|

| Refuse animal marketing authorization | Fluoroquinolones, Australia EMA tigecycline [65] |

| Restrict animal marketing authorization | extra-label use of cephalosporins in food-producing animals [66] in the USA |

| Revise animal marketing authorization | Colistin, EMA [67], introduced restrictions based on new information |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Edwards, S.E.; Morel, C.M.; Busse, R.; Harbarth, S. Combatting Antibiotic Resistance Together: How Can We Enlist the Help of Industry? Antibiotics 2018, 7, 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7040111

Edwards SE, Morel CM, Busse R, Harbarth S. Combatting Antibiotic Resistance Together: How Can We Enlist the Help of Industry? Antibiotics. 2018; 7(4):111. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7040111

Chicago/Turabian StyleEdwards, Suzanne E., Chantal M. Morel, Reinhard Busse, and Stephan Harbarth. 2018. "Combatting Antibiotic Resistance Together: How Can We Enlist the Help of Industry?" Antibiotics 7, no. 4: 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7040111

APA StyleEdwards, S. E., Morel, C. M., Busse, R., & Harbarth, S. (2018). Combatting Antibiotic Resistance Together: How Can We Enlist the Help of Industry? Antibiotics, 7(4), 111. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7040111