Fighting Fire with Fire: Phage Potential for the Treatment of E. coli O157 Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

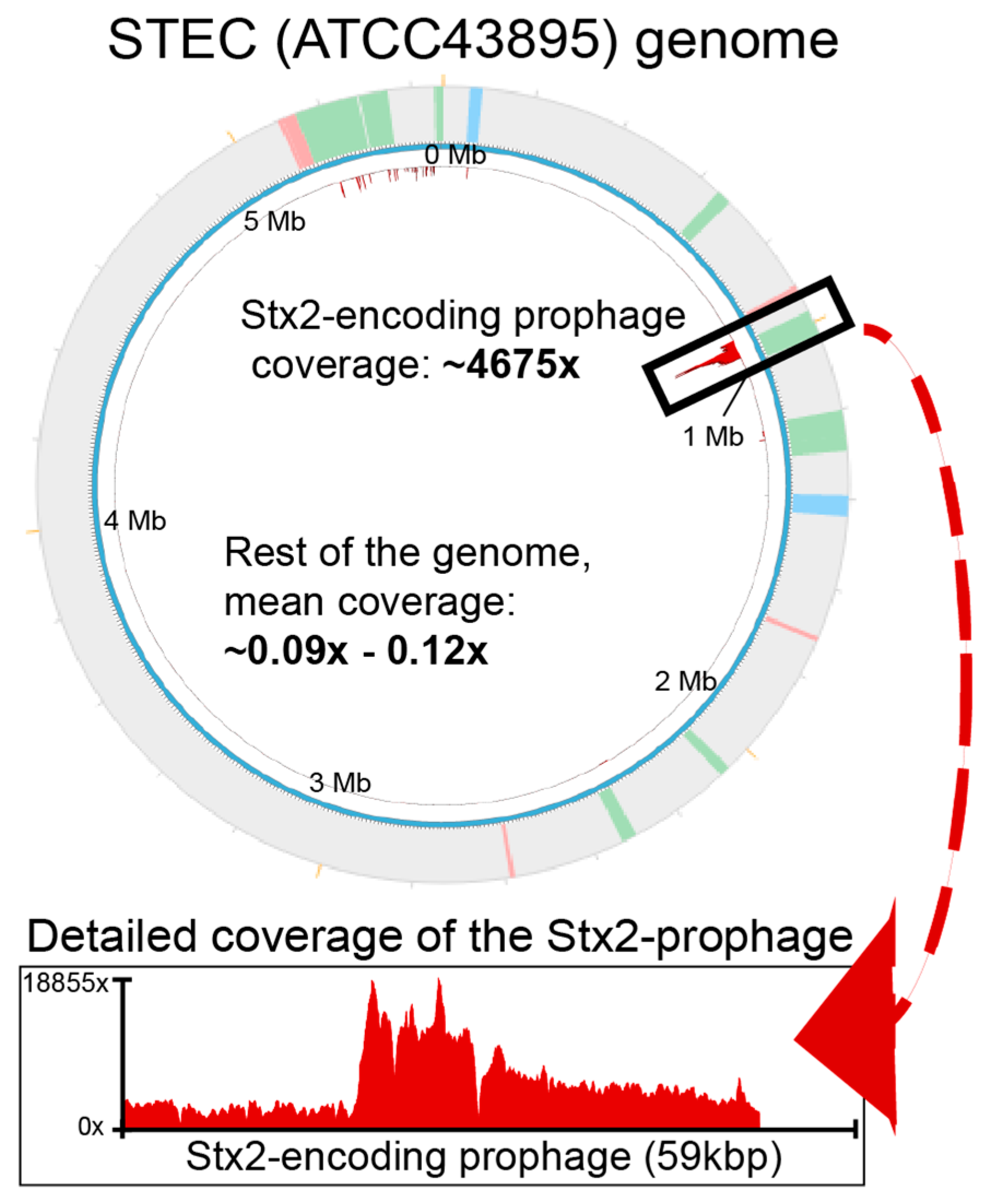

2.1. Detecting Spontaneous Prophage Induction

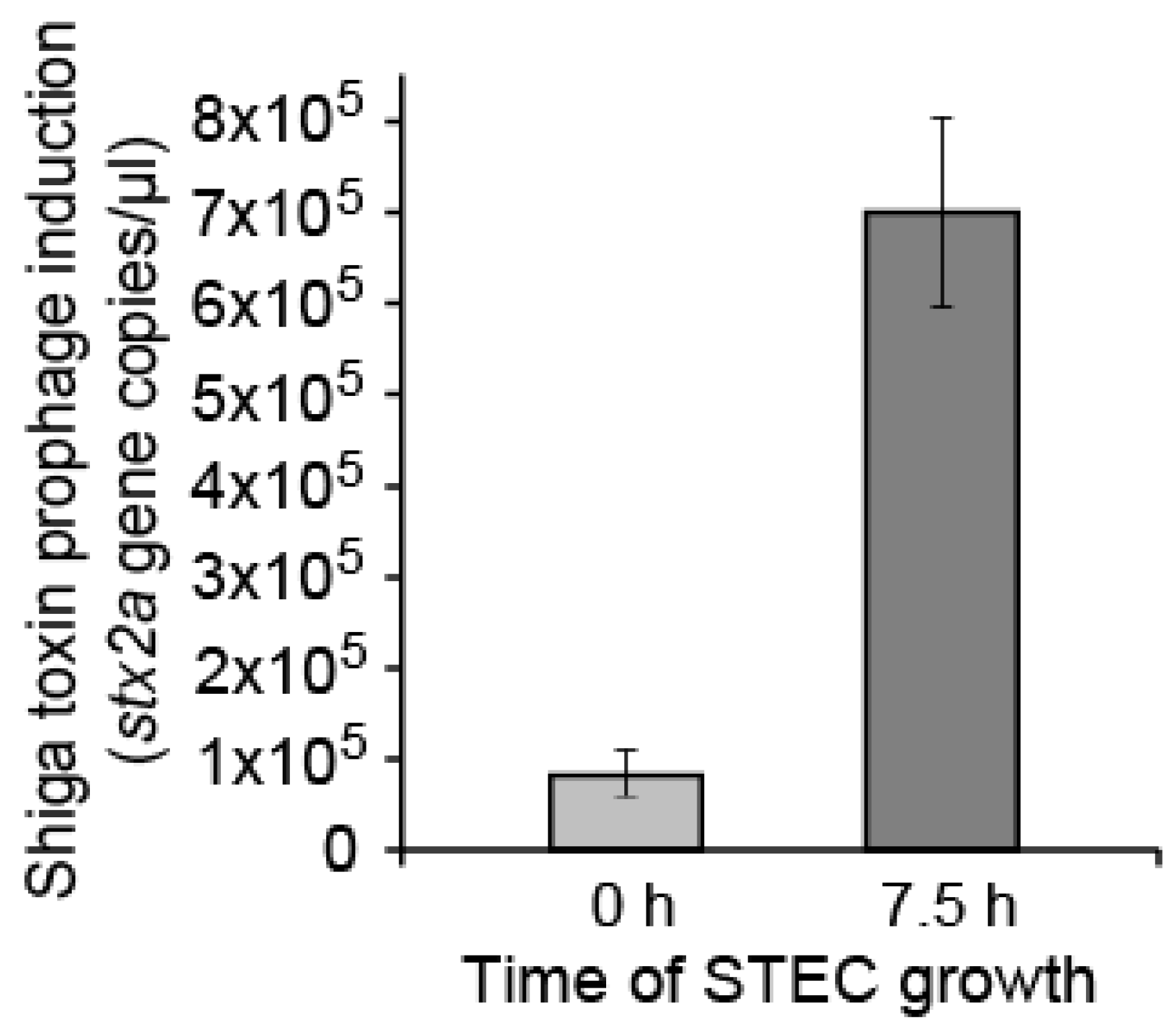

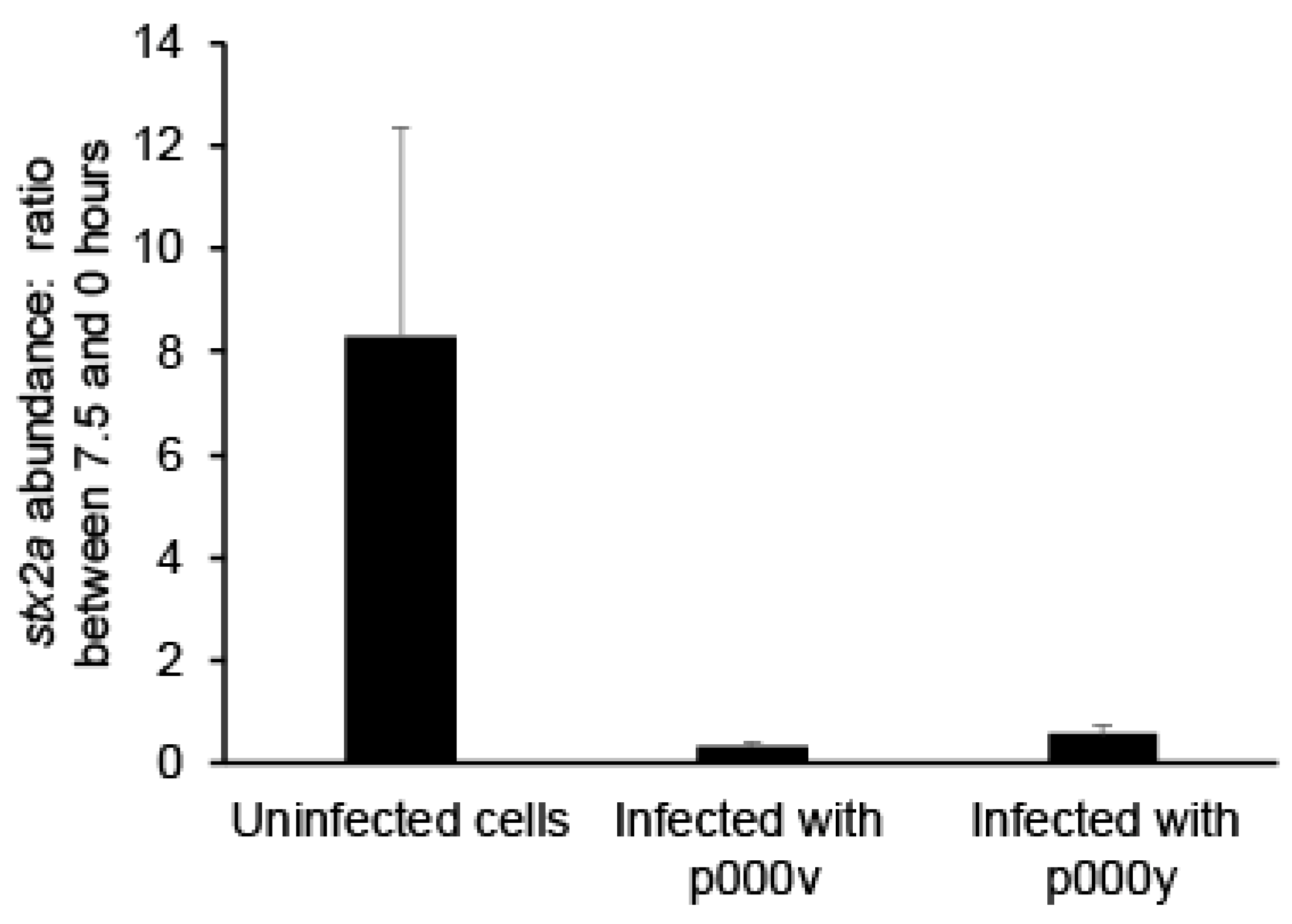

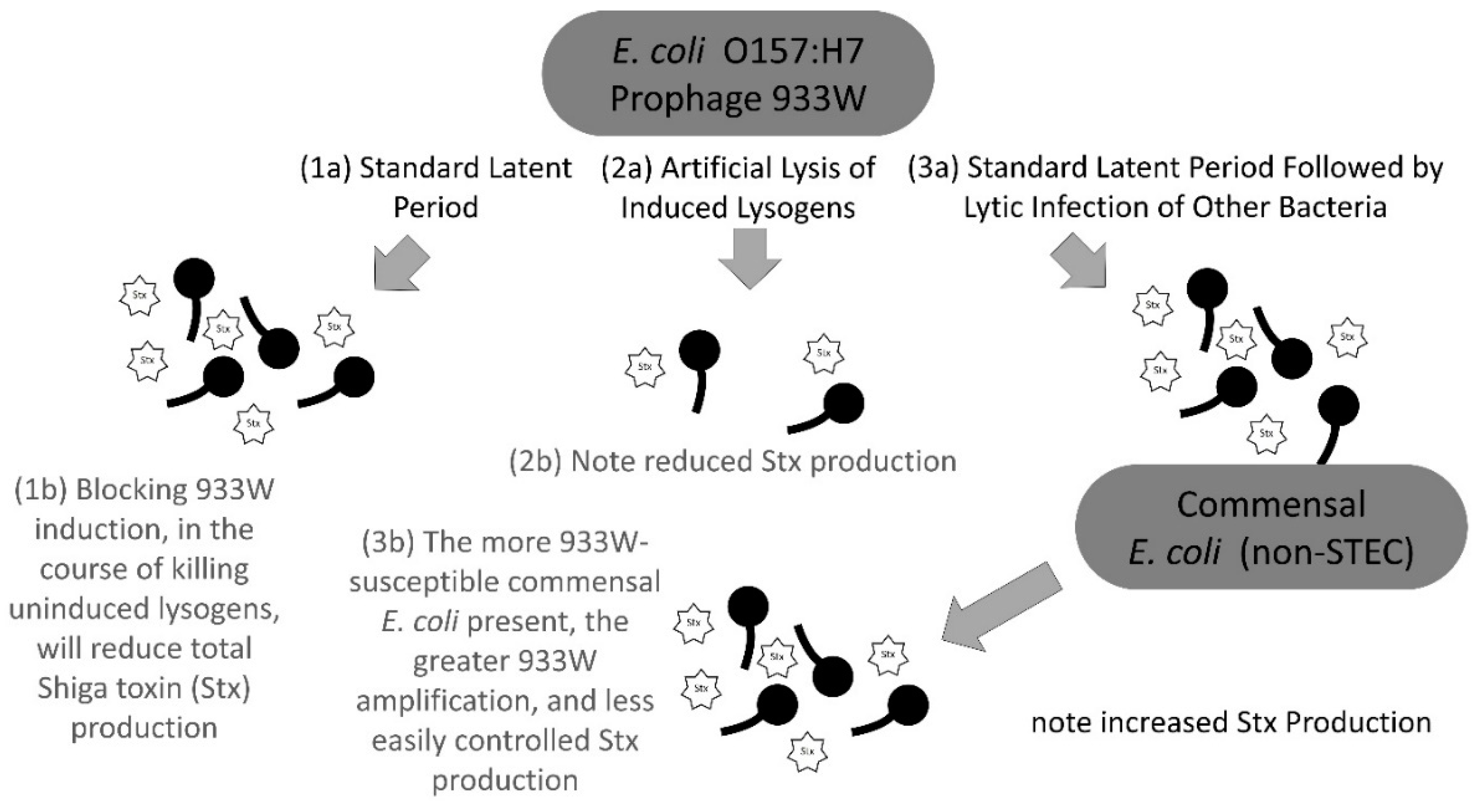

2.2. Fighting Prophage Induction with Phage Treatment

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strain and Phages Used in This Study

4.2. Cell Growth

4.3. Lysates for Phage Amplification

4.4. DNA Extraction

4.5. Library Preparation and Illumina Miseq Sequencing of Phage and Host Genomes

4.6. Whole-Genome Sequencing and Read-Mapping to Assess Prophage Induction

4.7. Read Mapping and Visualization of Prophage Induction

4.8. qPCR of Phage Lysates’ DNA

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Penades, J.R.; Chen, J.; Quiles-Puchalt, N.; Carpena, N.; Novick, R.P. Bacteriophage-mediated spread of bacterial virulence genes. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2015, 23, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feiner, R.; Argov, T.; Rabinovich, L.; Sigal, N.; Borovok, I.; Herskovits, A.A. A new perspective on lysogeny: Prophages as active regulatory switches of bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015, 13, 641–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard-Varona, C.; Hargreaves, K.R.; Abedon, S.T.; Sullivan, M.B. Lysogeny in nature: Mechanisms, impact and ecology of temperate phages. ISME J. 2017, 11, 1511–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortier, L.-C.; Sekulovic, O. Importance of prophages to evolution and virulence of bacterial pathogens. Virulence 2013, 4, 354–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, E.V.; Winstanley, C.; Fothergill, J.L.; James, C.E. The role of temperate bacteriophages in bacterial infection. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2016, 363, fnw015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touchon, M.; Bernheim, A.; Rocha, E.P.C. Genetic and life-history traits associated with the distribution of prophages in bacteria. ISME J. 2016, 10, 2744–2754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaper, J.B.; O’Brien, A.D. Overview and Historical Perspectives. Microbiol. Spectr. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabban, A.D.; Hite, E.; Callaway, T.R. Evolution of foodborne pathogens via temperate bacteriophage-mediated gene transfer. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2005, 2, 287–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melton-Celsa, A.R. Shiga Toxin (Stx) Classification, Structure, and Function. Microbiol. Spectr. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plunkett, G.; Rose, D.J.; Durfee, T.J.; Blattner, F.R. Sequence of Shiga Toxin 2 Phage 933W from Escherichia coli O157:H7: Shiga Toxin as a Phage Late-Gene Product. J. Bacteriol. 1999, 181, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar]

- Perna, N.T.; Plunkett, G.; Burland, V.; Mau, B.; Glasner, J.D.; Rose, D.J.; Mayhew, G.F.; Evans, P.S.; Gregor, J.; Kirkpatrick, H.A.; et al. Genome sequence of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nature 2001, 409, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latif, H.; Li, H.J.; Charusanti, P.; Palsson, B.O.; Aziz, R.K. A gapless, unambiguous genome sequence of the enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL933. Genome Announc. 2014, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colon, M.P.; Chakraborty, D.; Pevzner, Y.; Koudelka, G.B. Mechanisms that determine the differential stability of Stx(+) and Stx(−) lysogens. Toxins (Basel) 2016, 8, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iversen, H.; L’Abee-Lund, T.M.; Aspholm, M.; Arnesen, L.P.S.; Lindback, T. Commensal E. coli Stx2 lysogens produce high levels of phages after spontaneous prophage induction. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livny, J.; Friedman, D.I. Characterizing spontaneous induction of Stx encoding phages using a selectable reporter system. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 51, 1691–1704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, S.; Siebert, J.; Huber, A.; Schmidt, H. Global expression of prophage genes in Escherichia coli O157:H7 strain EDL933 in response to norfloxacin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 931–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadulghani, M.; Ogura, Y.; Ooka, T.; Itoh, T.; Sawaguchi, A.; Iguchi, A.; Nakayama, K.; Hayashi, T. The defective prophage pool of Escherichia coli O157: Prophage–prophage interactions potentiate horizontal transfer of virulence determinants. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5, e1000408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, S.; Karch, H.; Schmidt, H. Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages–genomes in motion. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 294, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łoś, J.M.; Łoś, M.; Węgrzyn, G.; Węgrzyn, A. Differential efficiency of induction of various lambdoid prophages responsible for production of Shiga toxins in response to different induction agents. Microb. Pathog. 2009, 47, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Los, J.M.; Los, M.; Wegrzyn, G. Bacteriophages carrying Shiga toxin genes: Genomic variations, detection and potential treatment of pathogenic bacteria. Future Microbiol. 2011, 6, 909–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, A.R.; Sperandio, V. Shiga toxin in enterohemorrhagic E. coli: Regulation and novel anti-virulence strategies. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obrig, T.G.; Karpman, D. Shiga toxin pathogenesis: Kidney complications and renal failure. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2012, 357, 105–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pruimboom-Brees, I.M.; Morgan, T.W.; Ackermann, M.R.; Nystrom, E.D.; Samuel, J.E.; Cornick, N.A.; Moon, H.W. Cattle lack vascular receptors for Escherichia coli O157:H7 Shiga toxins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 10325–10329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruger, A.; Lucchesi, P.M.A. Shiga toxins and stx phages: Highly diverse entities. Microbiology 2015, 161, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, P.L.; Waldor, M.K. Bacteriophage control of bacterial virulence. Infect. Immun. 2002, 70, 3985–3993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, S.B.; Xie, J.; Neufeld, M.S.; Hamilton, W.L.; Hartling, L.; Tarr, P.I.; Nettel-Aguirre, A.; Chuck, A.; Lee, B.; Johnson, D.; et al. Shiga Toxin-Producing Escherichia coli Infection, Antibiotics, and Risk of Developing Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome: A Meta-analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016, 62, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arndt, D.; Grant, J.R.; Marcu, A.; Sajed, T.; Pon, A.; Liang, Y.; Wishart, D.S. PHASTER: A better, faster version of the PHAST phage search tool. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W16–W21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hertel, R.; Rodríguez, D.P.; Hollensteiner, J.; Dietrich, S.; Leimbach, A.; Hoppert, M.; Liesegang, H.; Volland, S. Genome-based identification of active prophage regions by next generation sequencing in bacillus licheniformis DSM13. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0120759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Utter, B.; Deutsch, D.R.; Schuch, R.; Winer, B.Y.; Verratti, K.; Bishop-Lilly, K.; Sozhamannan, S.; Fischetti, V.A. Beyond the chromosome: The prevalence of unique extra-chromosomal bacteriophages with integrated virulence genes in pathogenic Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e100502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, F.; Wang, K.; Stewart, J.; Belas, R. Induction of multiple prophages from a marine bacterium: A genomic approach. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 4995–5001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, Y.; Mondal, S.I.; Islam, M.R.; Mako, T.; Arisawa, K.; Katsura, K.; Ooka, T.; Gotoh, Y.; Murase, K.; Ohnishi, M.; et al. The Shiga toxin 2 production level in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7 is correlated with the subtypes of toxin-encoding phage. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard-Varona, C.; Vik, D.R.; Solonenko, N.E.; Gazitua, M.C.; Hobbs, Z.; Honaker, R.W.; Kinkhabwala, A.A.; Sullivan, M.B. Whole-genome sequence of phages p000v and p000y infecting the bacterial pathogen Shigatoxigenic Escherichia coli. Press. Genome Announc. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; McDaniel, A.D.; Wolf, L.E.; Keusch, G.T.; Waldor, M.K.; Acheson, D.W. Quinolone antibiotics induce Shiga toxin-encoding bacteriophages, toxin production, and death in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 181, 664–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Los, J.M.; Los, M.; Wegrzyn, A.; Wegrzyn, G. Altruism of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: Recent hypothesis versus experimental results. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tyler, J.S.; Beeri, K.; Reynolds, J.L.; Alteri, C.J.; Skinner, K.G.; Friedman, J.H.; Eaton, K.A.; Friedman, D.I. Prophage induction is enhanced and required for renal disease and lethality in an EHEC mouse model. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9, e1003236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tarr, P.I. Escherichia coli O157:H7: Clinical, diagnostic, and epidemiological aspects of human infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1995, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpe, C.M. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2004, 38, 1298–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagner, P.L.; Neely, M.N.; Zhang, X.; Acheson, D.W.; Waldor, M.K.; Friedman, D.I. Role for a phage promoter in Shiga toxin 2 expression from a pathogenic Escherichia coli strain. J. Bacteriol. 2001, 183, 2081–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krysiak-Baltyn, K.; Martin, G.J.O.; Stickland, A.D.; Scales, P.J.; Gras, S.L. Computational models of populations of bacteria and lytic phage. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2016, 42, 942–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gamage, S.D.; Patton, A.K.; Strasser, J.E.; Chalk, C.L.; Weiss, A.A. Commensal bacteria influence Escherichia coli O157:H7 persistence and Shiga toxin production in the mouse intestine. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 1977–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acheson, D.W.; Reidl, J.; Zhang, X.; Keusch, G.T.; Mekalanos, J.J.; Waldor, M.K. In vivo transduction with shiga toxin 1-encoding phage. Infect. Immun. 1998, 66, 4496–4498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, H.; Bielaszewska, M.; Karch, H. Transduction of enteric Escherichia coli isolates with a derivative of Shiga toxin 2-encoding bacteriophage phi3538 isolated from Escherichia coli O157:H7. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1999, 65, 3855–3861. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Doron, S.; Fedida, A.; Hernandez-Prieto, M.A.; Sabehi, G.; Karunker, I.; Stazic, D.; Feingersch, R.; Steglich, C.; Futschik, M.; Lindell, D.; et al. Transcriptome dynamics of a broad host-range cyanophage and its hosts. ISME J. 2016, 10, 1437–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard-Varona, C.; Roux, S.; Dore, H.; Solonenko, N.E.; Holmfeldt, K.; Markillie, L.M.; Orr, G.; Sullivan, M.B. Regulation of infection efficiency in a globally abundant marine Bacteriodetes virus. ISME J. 2017, 11, 284–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard-Varona, C.; Hargreaves, K.R.; Solonenko, N.E.; Markillie, L.M.; White, R.A.; Brewer, H.M.; Ansong, C.; Orr, G.; Adkins, J.N.; Sullivan, M.B. Multiple mechanisms drive phage infection efficiency in nearly identical hosts. ISME J. 2018, 12, 1605–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abedon, S.T. Phage therapy: Eco-physiological pharmacology. Scientifica (Cairo) 2014, 2014, 581639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, S.A.; Berger, B.; Deng, Y.; Kieser, S.; Foata, F.; Moine, D.; Descombes, P.; Sultana, S.; Huq, S.; Bardhan, P.K.; et al. Oral application of Escherichia coli bacteriophage: Safety tests in healthy and diarrheal children from Bangladesh. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merchant, N.; Lyons, E.; Goff, S.; Vaughn, M.; Ware, D.; Micklos, D.; Antin, P. The iPlant collaborative: Cyberinfrastructure for enabling data to discovery for the life sciences. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1754–1760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Handsaker, B.; Wysoker, A.; Fennell, T.; Ruan, J.; Homer, N. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 2078–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabosky, D.L.; Grundler, M.; Anderson, C.; Title, P.; Shi, J.J.; Brown, J.W.; Huang, H.; Larson, J.G. BAMMtools: An R package for the analysis of evolutionary dynamics on phylogenetic trees. Methods Ecol. Evol. 2014, 5, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinlan, A.R.; Hall, I.M. BEDTools: A flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics 2010, 26, 841–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorvaldsdottir, H.; Robinson, J.T.; Mesirov, J.P. Integrative genomics viewer (IGV): High-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief. Bioinform. 2013, 14, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzywinski, M.I.; Schein, J.E.; Birol, I.; Connors, J.; Gascoyne, R.; Horsman, D.; Jones, S.J.; Marra, M.A. Circos: An information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Erez, Z.; Steinberger-Levy, I.; Shamir, M.; Doron, S.; Stokar-Avihail, A.; Peleg, Y.; Melamed, S.; Leavitt, A.; Savidor, A.; Albeck, S.; et al. Communication between viruses guides lysis–lysogeny decisions. Nature 2017, 541, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoichi, M.; Abe, M.; Miyanaga, K.; Unno, H.; Tanji, Y. Alteration of tail fiber protein gp38 enables T2 phage to infect Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 115, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yosef, I.; Goren, M.G.; Globus, R.; Molshanski-Mor, S.; Qimron, U. Extending the host range of bacteriophage particles for DNA transduction. Mol. Cell 2017, 66, 721.e3–728.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roach, D.R.; Debarbieux, L. Phage therapy: Awakening a sleeping giant. Emerg. Top. Life Sci. 2017, 1, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Lysate | Prophage or Not? | Genomic Entity | Raw Coverage | Coverage Normalized by Sequencing Depth and Entity Length | Final Adjusted Coverage (Raised to 1011) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No phage control ATCC43895 (STEC)-Replicate 1 | Prophages | #1-58370-85143 | 0.069 | 5.69 × 10−14 | 0.01 |

| #2-648527-680910 | 0.067 | 5.50 × 10−14 | 0.01 | ||

| #3 and 4-911029-938407 bp | 0.835 | 6.89 × 10−13 | 0.07 | ||

| #5 (Stx2)-973564-1032902 bp | 585.776 | 4.41 × 10−8 | 4407.33 | ||

| #6 and 7-1202175-1293616 bp | 2.606 | 2.15 × 10−12 | 0.22 | ||

| #8-1390536-1436457 bp | 0.018 | 1.47 × 10−14 | 0 | ||

| #9-1708731-1719671 bp | 0.002 | 1.57 × 10−15 | 0 | ||

| #10-2054278-2078426 bp | 0.167 | 1.38 × 10−13 | 0.01 | ||

| #11 (Stx1)-2302225-2335340 bp | 8.057 | 6.65 × 10−12 | 0.66 | ||

| #12-2579647-2589259 bp | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| #13, 14 and 15-5103469-5282316 bp | 1.229 | 1.01 × 10−12 | 0.1 | ||

| #16-5286283-5348617 bp | 0.274 | 2.26 × 10−13 | 0.02 | ||

| #17-5449904-5468395 bp | 0.24 | 1.98 × 10−13 | 0.02 | ||

| Non-prophage | Host genome, non-prophage | 0.852 | 7.04 × 10−13 | 0.07 | |

| No phage control ATCC43895 (STEC)-Replicate 2 | Prophages | #1-58370-85143 | 0.15 | 8.91 × 10−14 | 0.01 |

| #2-648527-680910 | 0.514 | 3.05 × 10−13 | 0.03 | ||

| #3 and 4-911029-938407 bp | 1.883 | 1.12 × 10−12 | 0.11 | ||

| #5 (Stx2)-973564-1032902 bp | 881.779 | 4.77 × 10−8 | 4774.17 | ||

| #6 and 7-1202175-1293616 bp | 4.605 | 2.74 × 10−12 | 0.27 | ||

| #8-1390536-1436457 bp | 0.118 | 7.00 × 10−14 | 0.01 | ||

| #9-1708731-1719671 bp | 0.22 | 1.30 × 10−13 | 0.01 | ||

| #10-2054278-2078426 bp | 0.372 | 2.21 × 10−13 | 0.02 | ||

| #11 (Stx1)-2302225-2335340 bp | 14.645 | 8.70 × 10−12 | 0.87 | ||

| #12-2579647-2589259 bp | 0.097 | 5.73 × 10−14 | 0.01 | ||

| #13, 14 and 15-5103469-5282316 bp | 2.283 | 1.36 × 10−12 | 0.14 | ||

| #16-5286283-5348617 bp | 0.437 | 2.59 × 10−13 | 0.03 | ||

| #17-5449904-5468395 bp | 0.562 | 3.34 × 10−13 | 0.03 | ||

| Non-prophage | Host genome, non-prophage | 1.743 | 1.04 × 10−12 | 0.1 | |

| No phage control ATCC43895 (STEC)-Replicate 3 | Prophages | #1-58370-85143 | 0.226 | 1.48 × 10−13 | 0.01 |

| #2-648527-680910 | 0.299 | 1.96 × 10−13 | 0.02 | ||

| #3 and 4-911029-938407 bp | 1.379 | 9.03 × 10−13 | 0.09 | ||

| #5 (Stx2)-973564-1032902 bp | 811.189 | 4.84 × 10−8 | 4844.55 | ||

| #6 and 7-1202175-1293616 bp | 4.466 | 2.93 × 10−12 | 0.29 | ||

| #8-1390536-1436457 bp | 0.089 | 5.82 × 10−14 | 0.01 | ||

| #9-1708731-1719671 bp | 0.117 | 7.66 × 10−14 | 0.01 | ||

| #10-2054278-2078426 bp | 0.399 | 2.61 × 10−13 | 0.03 | ||

| #11 (Stx1)-2302225-2335340 bp | 13.974 | 9.15 × 10−12 | 0.92 | ||

| #12-2579647-2589259 bp | 0.277 | 1.82 × 10−13 | 0.02 | ||

| #13, 14 and 15-5103469-5282316 bp | 2.031 | 1.33 × 10−12 | 0.13 | ||

| #16-5286283-5348617 bp | 0.345 | 2.26 × 10−13 | 0.02 | ||

| #17-5449904-5468395 bp | 0.541 | 3.54 × 10−13 | 0.04 | ||

| Non-prophage | Host genome, non-prophage | 1.681 | 1.10×10−12 | 0.11 |

| Stx2a Copies Per µL During STEC Growth with and without Phage | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage | 0 h | 7.5 h | Ratio | MOI |

| None | 8.39 × 104 | 6.97 × 105 | 8.31 | NA |

| p000v | 6.93 × 103 | 2.09 × 103 | 0.30 | 6.43 |

| p000y | 8.00 × 103 | 2.88 × 103 | 0.36 | 4.61 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Howard-Varona, C.; Vik, D.R.; Solonenko, N.E.; Li, Y.-F.; Gazitua, M.C.; Chittick, L.; Samiec, J.K.; Jensen, A.E.; Anderson, P.; Howard-Varona, A.; et al. Fighting Fire with Fire: Phage Potential for the Treatment of E. coli O157 Infection. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7040101

Howard-Varona C, Vik DR, Solonenko NE, Li Y-F, Gazitua MC, Chittick L, Samiec JK, Jensen AE, Anderson P, Howard-Varona A, et al. Fighting Fire with Fire: Phage Potential for the Treatment of E. coli O157 Infection. Antibiotics. 2018; 7(4):101. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7040101

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoward-Varona, Cristina, Dean R. Vik, Natalie E. Solonenko, Yueh-Fen Li, M. Consuelo Gazitua, Lauren Chittick, Jennifer K. Samiec, Aubrey E. Jensen, Paige Anderson, Adrian Howard-Varona, and et al. 2018. "Fighting Fire with Fire: Phage Potential for the Treatment of E. coli O157 Infection" Antibiotics 7, no. 4: 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7040101

APA StyleHoward-Varona, C., Vik, D. R., Solonenko, N. E., Li, Y.-F., Gazitua, M. C., Chittick, L., Samiec, J. K., Jensen, A. E., Anderson, P., Howard-Varona, A., Kinkhabwala, A. A., Abedon, S. T., & Sullivan, M. B. (2018). Fighting Fire with Fire: Phage Potential for the Treatment of E. coli O157 Infection. Antibiotics, 7(4), 101. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7040101