Establishing a System for Testing Replication Inhibition of the Vibrio cholerae Secondary Chromosome in Escherichia coli

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

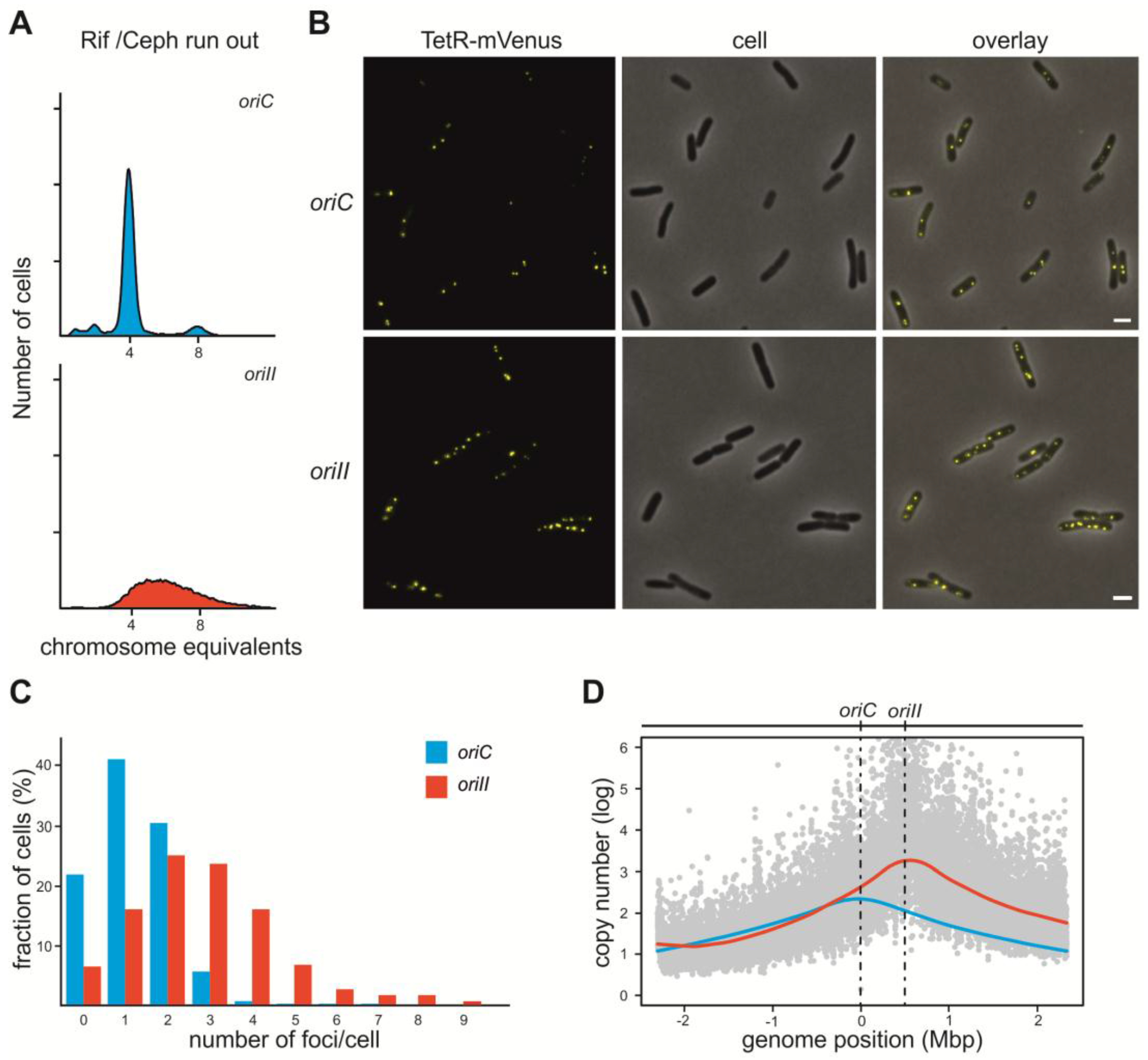

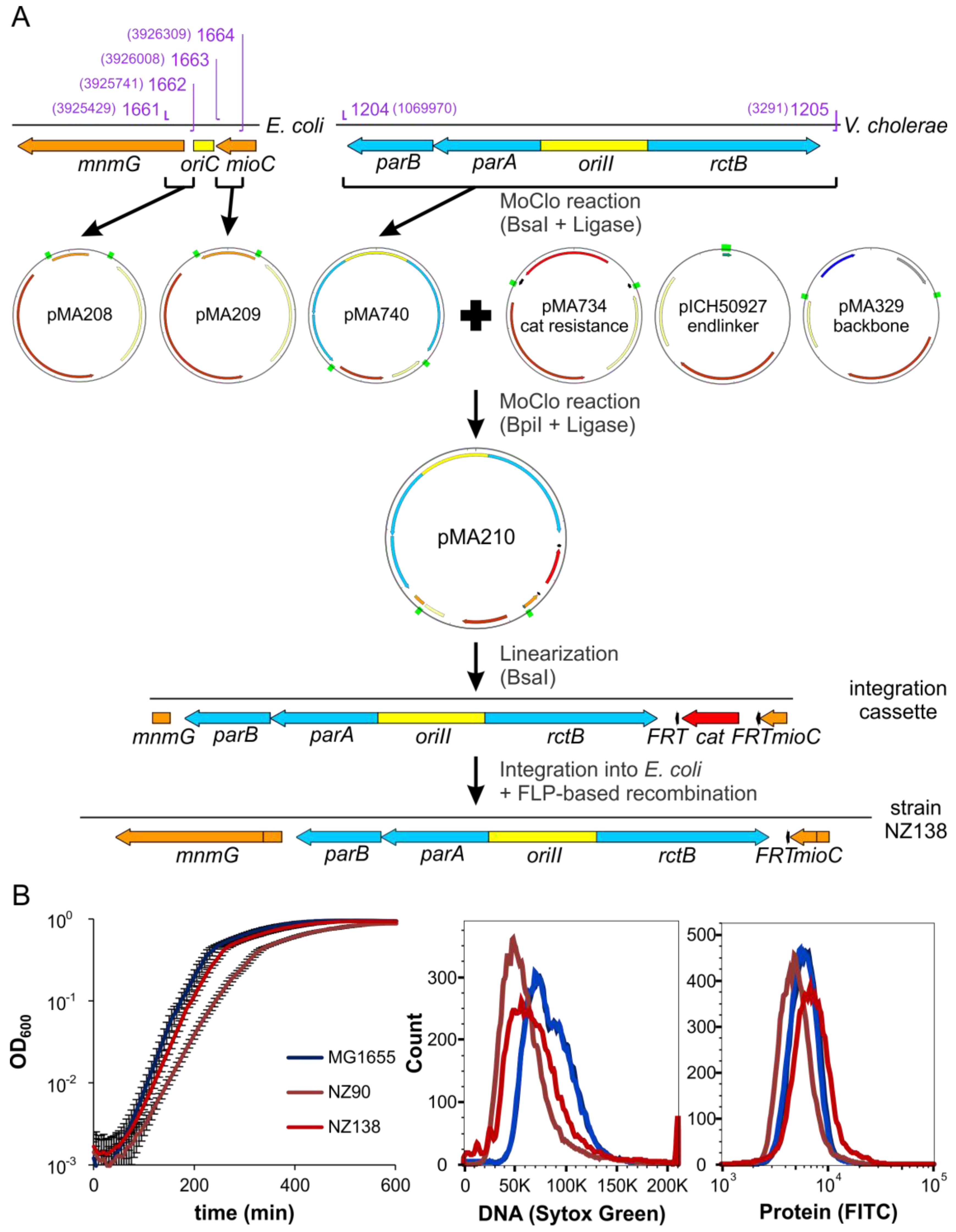

2.1. V. Cholerae ori2 Dependent Replication of the E. coli Chromosome

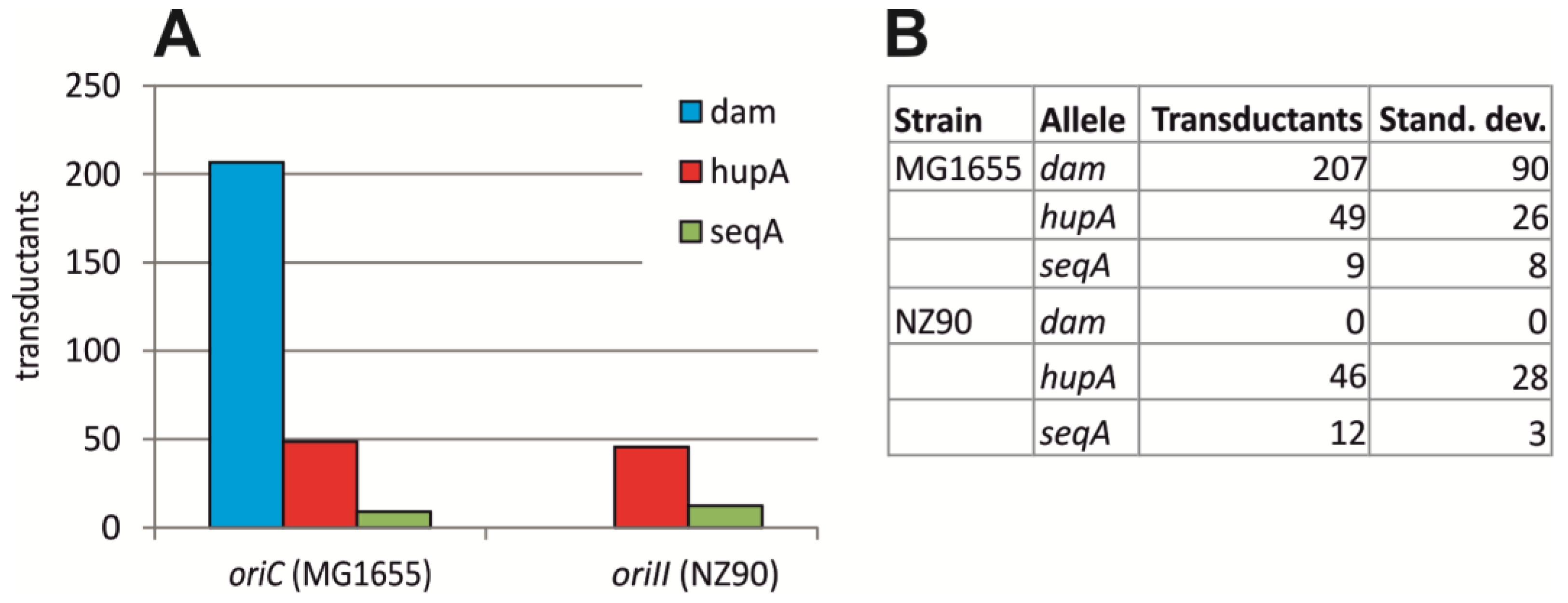

2.2. Initiation of Replication at ori2 in E. coli Depends on Dam Methylation

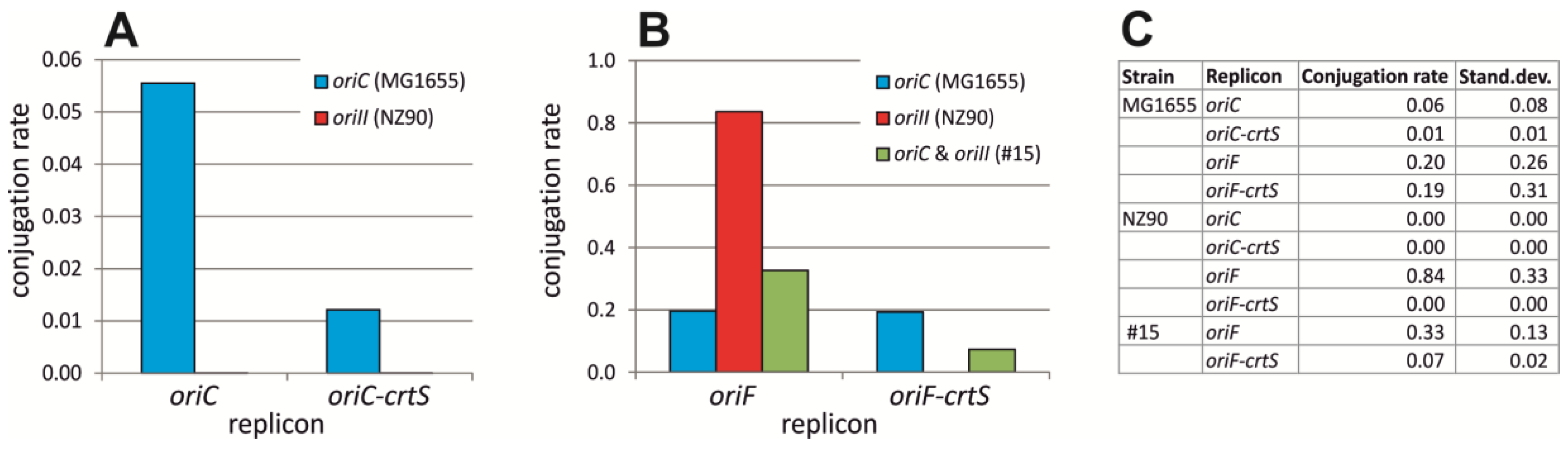

2.3. crtS-Dependent Regulation of ori2-Based Replication in E. coli

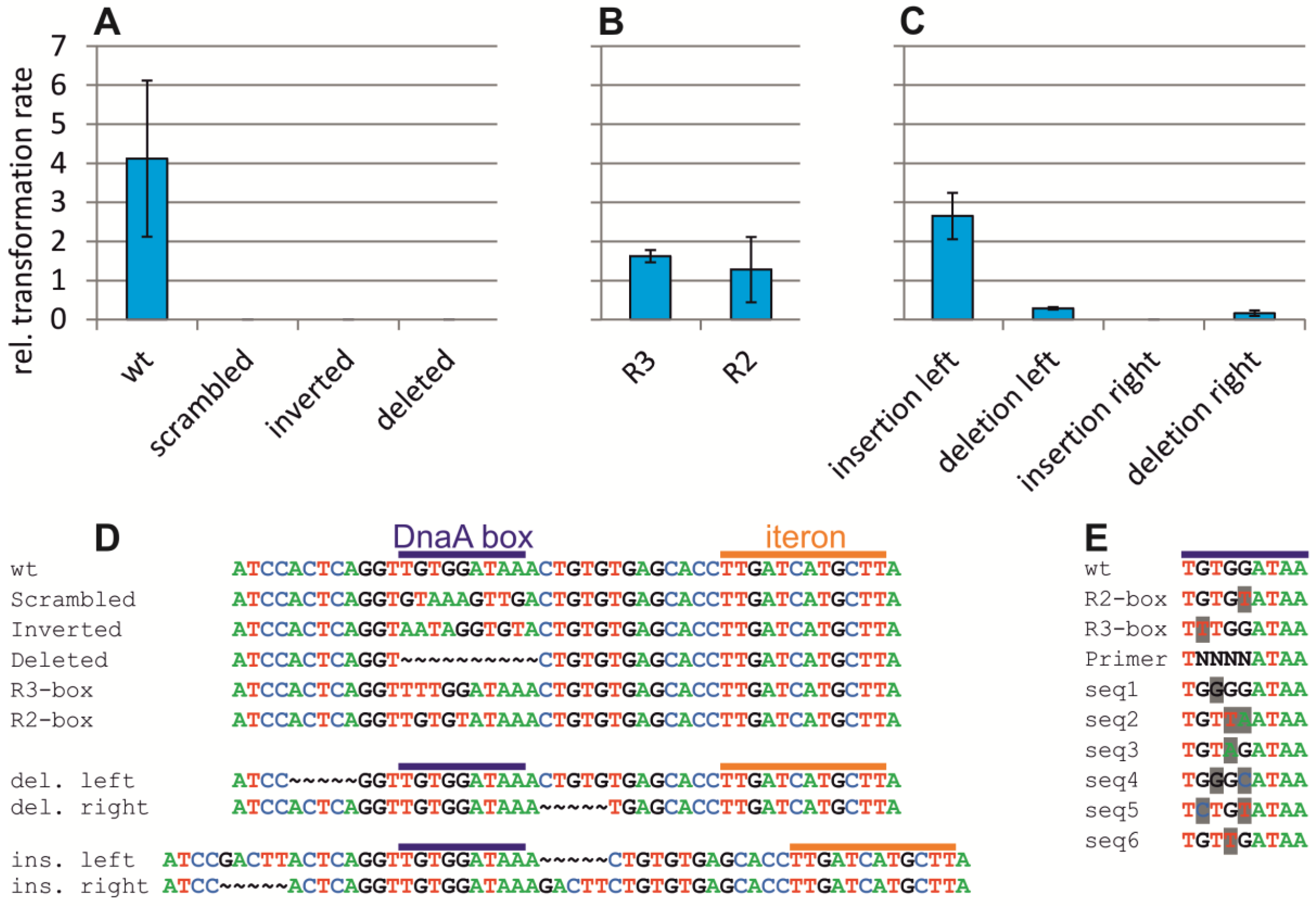

2.4. Assaying the DnaA-Box in ori2 for Its Role in Replication Initiation

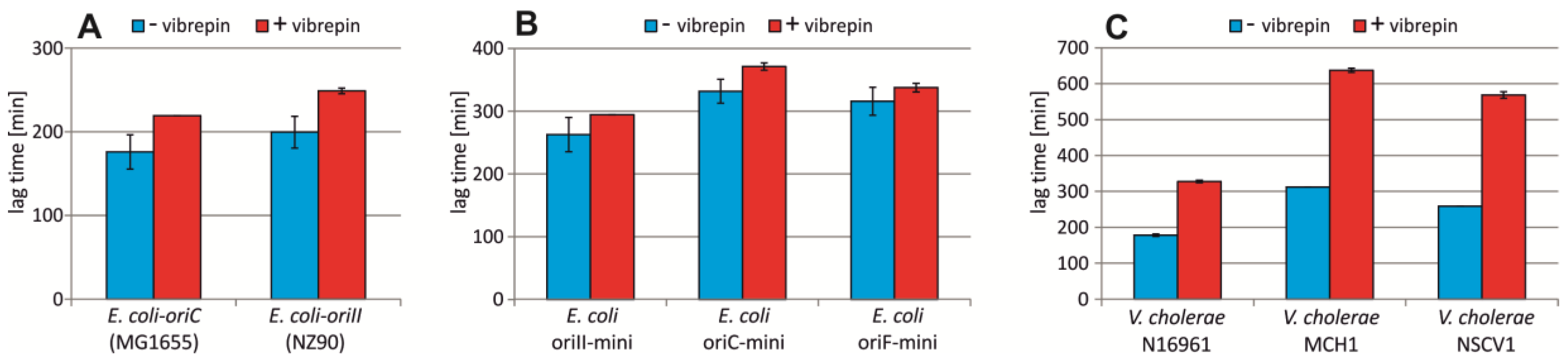

2.5. Vibrepin Does Not Inhibit ori2-Dependent Replication

2.6. ori2 Can Replace oriC in E. coli

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, Oligonucleotides, and Culture Conditions

4.2. P1 Transduction

4.3. Conjugation

4.4. Quantification of Replicon Copy Numbers by qPCR

4.5. Quantification of Replicon Copy Number via Antibiotic Sensitivity

4.6. Comparative Genomic Hybridization

4.7. Flow Cytometry

4.8. Fluorescence Microscopy and Data Evaluation

4.9. Plasmid Construction

4.10. Strain Construction

Supplementary Materials

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kuzminov, A. The precarious prokaryotic chromosome. J. Bacteriol. 2014, 196, 1793–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, J.K.; Baek, J.H.; Venkova-Canova, T.; Chattoraj, D.K. Chromosome dynamics in multichromosome bacteria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1819, 826–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.W.; Huang, C.H.; Lee, H.H.; Tsai, H.H.; Kirby, R. Once the circle has been broken: Dynamics and evolution of Streptomyces chromosomes. Trends Genet. 2002, 18, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val, M.E.; Soler-Bistue, A.; Bland, M.J.; Mazel, D. Management of multipartite genomes: The Vibrio cholerae model. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014, 22, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, E.S.; Waldor, M.K. Distinct replication requirements for the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. Cell 2003, 114, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heidelberg, J.F.; Eisen, J.A.; Nelson, W.C.; Clayton, R.A.; Gwinn, M.L.; Dodson, R.J.; Haft, D.H.; Hickey, E.K.; Peterson, J.D.; Umayam, L.; et al. DNA sequence of both chromosomes of the cholera pathogen Vibrio cholerae. Nature 2000, 406, 477–483. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Duigou, S.; Knudsen, K.G.; Skovgaard, O.; Egan, E.S.; Lobner-Olesen, A.; Waldor, M.K. Independent control of replication initiation of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes by DnaA and RctB. J. Bacteriol. 2006, 188, 6419–6424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duigou, S.; Yamaichi, Y.; Waldor, M.K. ATP negatively regulates the initiator protein of Vibrio cholerae chromosome II replication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2008, 105, 10577–10582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, J.K.; Ghirlando, R.; Chattoraj, D.K. Initiator protein dimerization plays a key role in replication control of Vibrio cholerae chromosome 2. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 10538–10549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orlova, N.; Gerding, M.; Ivashkiv, O.; Olinares, P.D.B.; Chait, B.T.; Waldor, M.K.; Jeruzalmi, D. The replication initiator of the cholera pathogen’s second chromosome shows structural similarity to plasmid initiators. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 3724–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, J.K.; Li, M.; Ghirlando, R.; Miller Jenkins, L.M.; Wlodawer, A.; Chattoraj, D. The DnaK chaperone uses different mechanisms to promote and inhibit replication of Vibrio cholerae chromosome 2. Mbio 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkova-Canova, T.; Chattoraj, D.K. Transition from a plasmid to a chromosomal mode of replication entails additional regulators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, 6199–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demarre, G.; Chattoraj, D.K. DNA adenine methylation is required to replicate both Vibrio cholerae chromosomes once per cell cycle. PLoS Genet. 2010, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, B.; Ma, X.; Lobner-Olesen, A. Replication of Vibrio cholerae chromosome I in Escherichia coli: Dependence on dam methylation. J. Bacteriol. 2010, 192, 3903–3914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egan, E.S.; Lobner-Olesen, A.; Waldor, M.K. Synchronous replication initiation of the two Vibrio cholerae chromosomes. Curr. Biol. 2004, 14, R501–R502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chao, M.C.; Pritchard, J.R.; Zhang, Y.J.; Rubin, E.J.; Livny, J.; Davis, B.M.; Waldor, M.K. High-resolution definition of the Vibrio cholerae essential gene set with hidden Markov model-based analyses of transposon-insertion sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013, 41, 9033–9048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamp, H.D.; Patimalla-Dipali, B.; Lazinski, D.W.; Wallace-Gadsden, F.; Camilli, A. Gene fitness landscapes of Vibrio cholerae at important stages of its life cycle. PLoS Pathog. 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jha, J.K.; Demarre, G.; Venkova-Canova, T.; Chattoraj, D.K. Replication regulation of Vibrio cholerae chromosome II involves initiator binding to the origin both as monomer and as dimer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 6026–6038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerding, M.A.; Chao, M.C.; Davis, B.M.; Waldor, M.K. Molecular dissection of the essential features of the origin of replication of the second Vibrio cholerae chromosome. Mbio 2015, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baek, J.H.; Chattoraj, D.K. Chromosome I controls chromosome II replication in Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Val, M.E.; Marbouty, M.; de Lemos Martins, F.; Kennedy, S.P.; Kemble, H.; Bland, M.J.; Possoz, C.; Koszul, R.; Skovgaard, O.; Mazel, D. A checkpoint control orchestrates the replication of the two chromosomes of Vibrio cholerae. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, T.; Jensen, R.B.; Skovgaard, O. The two chromosomes of Vibrio cholerae are initiated at different time points in the cell cycle. EMBO J. 2007, 26, 3124–3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stokke, C.; Waldminghaus, T.; Skarstad, K. Replication patterns and organization of replication forks in Vibrio cholerae. Microbiology 2011, 157, 695–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Val, M.E.; Kennedy, S.P.; Soler-Bistue, A.J.; Barbe, V.; Bouchier, C.; Ducos-Galand, M.; Skovgaard, O.; Mazel, D. Fuse or die: How to survive the loss of Dam in Vibrio cholerae. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 91, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.; Baek, C.H.; Katzen, F. Escherichia coli with two linear chromosomes. ACS Synth. Biol. 2013, 2, 734–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarstad, K.; Steen, H.B.; Boye, E. Cell cycle parameters of slowly growing Escherichia coli B/r studied by flow cytometry. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 154, 656–662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schindler, D.; Milbredt, S.; Sperlea, T.; Waldminghaus, T. Design and assembly of DNA sequence libraries for chromosomal insertion in bacteria based on a set of modified moclo vectors. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016, 5, 1362–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, L.A.; Breier, A.M.; Cozzarelli, N.R.; Kaguni, J.M. Hyperinitiation of DNA replication in Escherichia coli leads to replication fork collapse and inviability. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 51, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbredt, S.; Farmani, N.; Sobetzko, P.; Waldminghaus, T. DNA Replication in engineered Escherichia coli genomes with extra replication origins. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016, 5, 1167–1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Julio, S.M.; Heithoff, D.M.; Provenzano, D.; Klose, K.E.; Sinsheimer, R.L.; Low, D.A.; Mahan, M.J. DNA adenine methylase is essential for viability and plays a role in the pathogenesis of Yersinia pseudotuberculosis and Vibrio cholerae. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 7610–7615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhlin, B.E.; Nordstrom, K. Plasmid incompatibility and control of replication: Copy mutants of the R-factor R1 in Escherichia coli K-12. J. Bacteriol. 1975, 124, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Carleton, S.; Projan, S.J.; Highlander, S.K.; Moghazeh, S.M.; Novick, R.P. Control of pT181 replication II. Mutational analysis. EMBO J. 1984, 3, 2407–2414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Messerschmidt, S.J.; Schindler, D.; Zumkeller, C.M.; Kemter, F.S.; Schallopp, N.; Waldminghaus, T. Optimization and characterization of the synthetic secondary chromosome synVicII in Escherichia coli. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2016, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.B.; Asai, T.; Cao, Y.; Chambers, M.W.; Cadwell, G.W.; Boye, E.; Kogoma, T. The DnaA box R4 in the minimal oriC is dispensable for initiation of Escherichia coli chromosome replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 3119–3125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaichi, Y.; Duigou, S.; Shakhnovich, E.A.; Waldor, M.K. Targeting the replication initiator of the second Vibrio chromosome: Towards generation of vibrionaceae-specific antimicrobial agents. PLoS Pathog. 2009, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Val, M.E.; Skovgaard, O.; Ducos-Galand, M.; Bland, M.J.; Mazel, D. Genome engineering in Vibrio cholerae: A feasible approach to address biological issues. PLoS Genet. 2012, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, G.; Johnson, S.L.; Davenport, K.W.; Rajavel, M.; Waldminghaus, T.; Detter, J.C.; Chain, P.S.; Sozhamannan, S. Exception to the rule: Genomic characterization of naturally occurring unusual Vibrio cholerae strains with a single chromosome. Int. J. Genom. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messerschmidt, S.J.; Kemter, F.S.; Schindler, D.; Waldminghaus, T. Synthetic secondary chromosomes in Escherichia coli based on the replication origin of chromosome II in Vibrio cholerae. Biotechnol. J. 2015, 10, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fossum, S.; De Pascale, G.; Weigel, C.; Messer, W.; Donadio, S.; Skarstad, K. A robust screen for novel antibiotics: Specific knockout of the initiator of bacterial DNA replication. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008, 281, 210–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobner-Olesen, A.; Atlung, T.; Rasmussen, K.V. Stability and replication control of Escherichia coli minichromosomes. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 2835–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lobner-Olesen, A. Distribution of minichromosomes in individual Escherichia coli cells: Implications for replication control. EMBO J. 1999, 18, 1712–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarstad, K.; Lobner-Olesen, A. Stable co-existence of separate replicons in Escherichia coli is dependent on once-per-cell-cycle initiation. EMBO J. 2003, 22, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, T.T.; Harran, O.; Murray, H. The bacterial DnaA-trio replication origin element specifies single-stranded DNA initiator binding. Nature 2016, 534, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camara, J.E.; Breier, A.M.; Brendler, T.; Austin, S.; Cozzarelli, N.R.; Crooke, E. Hda inactivation of DnaA is the predominant mechanism preventing hyperinitiation of Escherichia coli DNA replication. EMBO Rep. 2005, 6, 736–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simmons, L.A.; Kaguni, J.M. The DnaAcos allele of Escherichia coli: Hyperactive initiation is caused by substitution of A184V and Y271H, resulting in defective ATP binding and aberrant DNA replication control. Mol. Microbiol. 2003, 47, 755–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, K.; Tomizawa, J. Establishment of Escherichia coli cells with an integrated high copy number plasmid. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1980, 178, 525–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, E.B.; Yarmolinsky, M.B. Host participation in plasmid maintenance: Dependence upon dnaA of replicons derived from P1 and F. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1986, 83, 4423–4427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldminghaus, T.; Skarstad, K. The Escherichia coli SeqA protein. Plasmid 2009, 61, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saint-Dic, D.; Kehrl, J.; Frushour, B.; Kahng, L.S. Excess SeqA leads to replication arrest and a cell division defect in Vibrio cholerae. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 5870–5878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, K.C.; Ryan, V.T.; Grimwade, J.E.; Leonard, A.C. Two discriminatory binding sites in the Escherichia coli replication origin are required for DNA strand opening by initiator DnaA-ATP. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 2811–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkova-Canova, T.; Baek, J.H.; Fitzgerald, P.C.; Blokesch, M.; Chattoraj, D.K. Evidence for two different regulatory mechanisms linking replication and segregation of Vibrio cholerae chromosome II. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, J.H. A Short Course in Bacterial Genetics: A Laboratory Manual and Handbook for Escherichia coli and Related Bacteria; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen, L.; Flatten, I.; Morigen; Dalhus, B.; Bjoras, M.; Waldminghaus, T.; Skarstad, K. The G157C mutation in the Escherichia coli sliding clamp specifically affects initiation of replication. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 79, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boye, E.; Lobner-Olesen, A.; Skarstad, K. Timing of chromosomal replication in Escherichia coli. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1988, 951, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldminghaus, T.; Weigel, C.; Skarstad, K. Replication fork movement and methylation govern SeqA binding to the Escherichia coli chromosome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 5465–5476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, C.; Brown, P.J.; Ducret, A.; Brun, Y.V. Sequential evolution of bacterial morphology by co-option of a developmental regulator. Nature 2014, 506, 489–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, D.G.; Young, L.; Chuang, R.Y.; Venter, J.C.; Hutchison, C.A., III; Smith, H.O. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, E.; Engler, C.; Gruetzner, R.; Werner, S.; Marillonnet, S. A modular cloning system for standardized assembly of multigene constructs. PLoS ONE 2011, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, V.L.; Mekalanos, J.J. A novel suicide vector and its use in construction of insertion mutations: Osmoregulation of outer membrane proteins and virulence determinants in Vibrio cholerae requires toxR. J. Bacteriol. 1988, 170, 2575–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherepanov, P.P.; Wackernagel, W. Gene disruption in Escherichia coli: TcR and KmR cassettes with the option of Flp-catalyzed excision of the antibiotic-resistance determinant. Gene 1995, 158, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schallopp, N.; Milbredt, S.; Sperlea, T.; Kemter, F.S.; Bruhn, M.; Schindler, D.; Waldminghaus, T. Establishing a System for Testing Replication Inhibition of the Vibrio cholerae Secondary Chromosome in Escherichia coli. Antibiotics 2018, 7, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7010003

Schallopp N, Milbredt S, Sperlea T, Kemter FS, Bruhn M, Schindler D, Waldminghaus T. Establishing a System for Testing Replication Inhibition of the Vibrio cholerae Secondary Chromosome in Escherichia coli. Antibiotics. 2018; 7(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchallopp, Nadine, Sarah Milbredt, Theodor Sperlea, Franziska S. Kemter, Matthias Bruhn, Daniel Schindler, and Torsten Waldminghaus. 2018. "Establishing a System for Testing Replication Inhibition of the Vibrio cholerae Secondary Chromosome in Escherichia coli" Antibiotics 7, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7010003

APA StyleSchallopp, N., Milbredt, S., Sperlea, T., Kemter, F. S., Bruhn, M., Schindler, D., & Waldminghaus, T. (2018). Establishing a System for Testing Replication Inhibition of the Vibrio cholerae Secondary Chromosome in Escherichia coli. Antibiotics, 7(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics7010003