Metagenomic Comparison of Bat Colony Resistomes Across Anthropogenic and Pristine Habitats

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Bat Species and Reads Quality Control

2.2. Metagenome-Assembled Genomes

2.3. Antimicrobial Resistance Genes

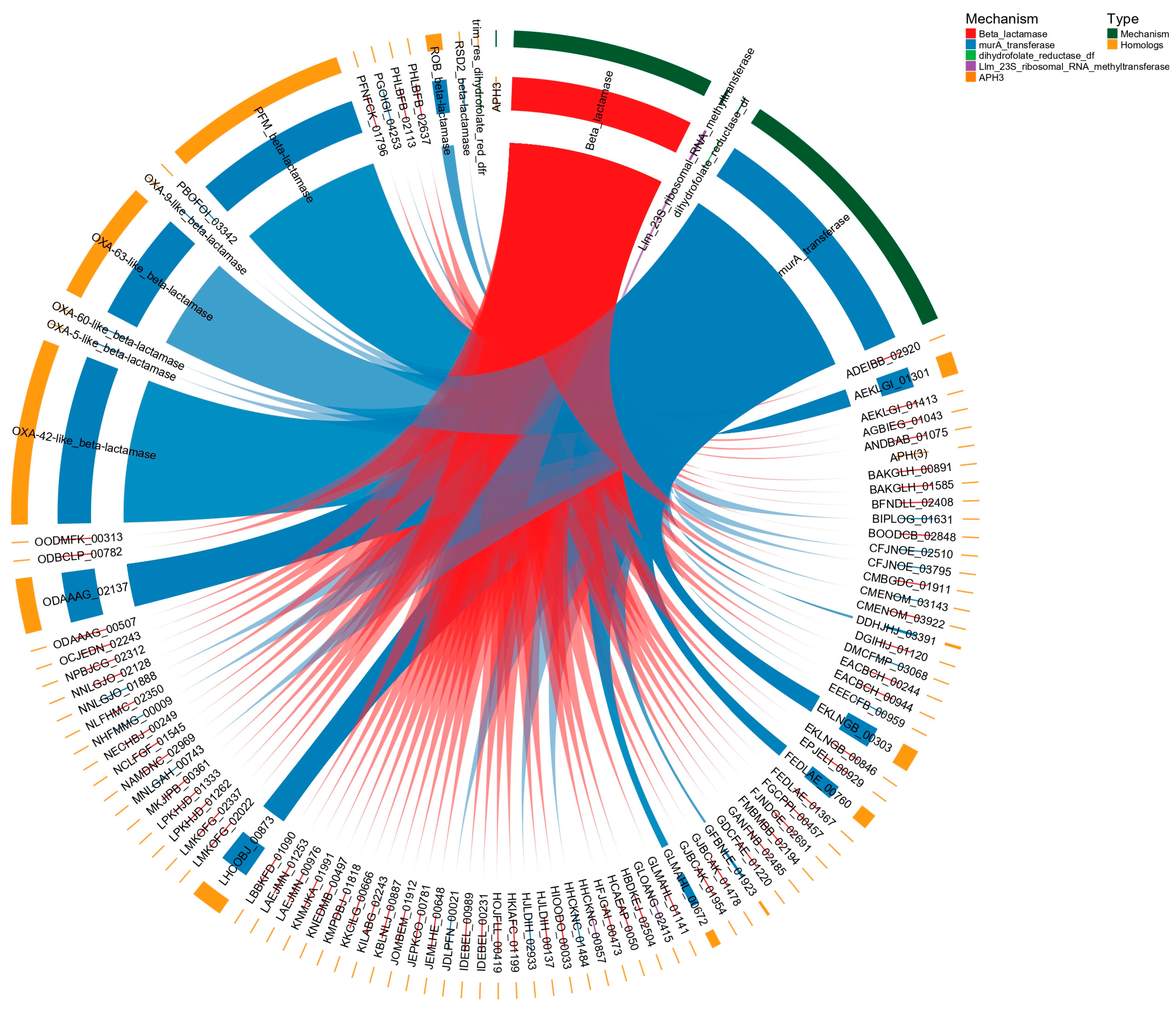

2.4. Homologous Mechanisms

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sample Collection

4.2. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

4.3. Study Selection and Data Retrieval of Control Data

4.4. Metagenome Preprocessing and Assembly

4.5. Methodology for Diversity and Differential Abundance Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nayfach, S.; Roux, S.; Seshadri, R.; Udwary, D.; Varghese, N.; Schulz, F.; Wu, D.; Paez-Espino, D.; Chen, I.-M.; Huntemann, M.; et al. A genomic catalog of Earth’s microbiomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seshadri, R.; Leahy, S.C.; Attwood, G.T.; Teh, K.H.; Lambie, S.C.; Cookson, A.L.; Eloe-Fadrosh, E.A.; Pavlopoulos, G.A.; Hadjithomas, M.; Varghese, N.J.; et al. Cultivation and sequencing of rumen microbiome members from the Hungate1000 Collection. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, L.R.; Sanders, J.G.; McDonald, D.; Amir, A.; Ladau, J.; Locey, K.J.; Prill, R.J.; Tripathi, A.; Gibbons, S.M.; Ackermann, G.; et al. A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature 2017, 551, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M.; Zengler, K. Tapping into microbial diversity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, A.K.; Kelly, S.A.; Legge, R.; Ma, F.; Low, S.J.; Kim, J.; Zhang, M.; Lyn, P.L.; Nehrenberg, D.; Hua, K.; et al. Individuality in gut microbiota composition is a complex polygenic trait shaped by multiple environmental and host genetic factors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 18933–18938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muegge, B.D.; Kuczynski, J.; Knights, D.; Clemente, J.C.; González, A.; Fontana, L.; Henrissat, B.; Knight, R.; Gordon, J.I. Diet Drives Convergence in Gut Microbiome Functions Across Mammalian Phylogeny and Within Humans. Science 2011, 332, 970–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ley, R.E.; Hamady, M.; Lozupone, C.; Turnbaugh, P.J.; Ramey, R.R.; Bircher, J.S.; Schlegel, M.L.; Tucker, T.A.; Schrenzel, M.D.; Knight, R.; et al. Evolution of Mammals and Their Gut Microbes. Science 2008, 320, 1647–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; Qin, J.; Lu, N.; Cheng, G.; Wu, N.; Pan, Y.; Li, J.; Zhu, L.; Wang, X.; et al. Metagenome-wide analysis of antibiotic resistance genes in a large cohort of human gut microbiota. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, L.; Estellé, J.; Kiilerich, P.; Ramayo-Caldas, Y.; Xia, Z.; Feng, Q.; Liang, S.; Pedersen, A.O.; Kjeldsen, N.J.; Liu, C.; et al. A reference gene catalogue of the pig gut microbiome. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson-Palme, J.; Kristiansson, E.; Larsson, D.G.J. Environmental factors influencing the development and spread of antibiotic resistance. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 42, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, S. Understanding the contribution of environmental factors in the spread of antimicrobial resistance. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2015, 20, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Thomsen, L.E.; Olsen, J.E. Antimicrobial-induced horizontal transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes in bacteria: A mini-review. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2022, 77, 556–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.M.; Nielsen, K.M. Mechanisms of, and Barriers to, Horizontal Gene Transfer between Bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005, 3, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Y.-X.; Anupoju, S.M.B.; Nguyen, A.; Zhang, H.; Ponder, M.; Krometis, L.-A.; Pruden, A.; Liao, J. Evidence of horizontal gene transfer and environmental selection impacting antibiotic resistance evolution in soil-dwelling Listeria. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 10034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, L.; Masulli, M.; De Laurenzi, V.; Allocati, N. An overview of bats microbiota and its implication in transmissible diseases. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1012189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingala, M.R.; Simmons, N.B.; Wultsch, C.; Krampis, K.; Speer, K.A.; Perkins, S.L. Comparing Microbiome Sampling Methods in a Wild Mammal: Fecal and Intestinal Samples Record Different Signals of Host Ecology, Evolution. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimkić, I.; Fira, D.; Janakiev, T.; Kabić, J.; Stupar, M.; Nenadić, M.; Unković, N.; Grbić, M.L. The microbiome of bat guano: For what is this knowledge important? Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 1407–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obodoechi, L.O.; Carvalho, I.; Chenouf, N.S.; Martínez-Álvarez, S.; Sadi, M.; Nwanta, J.A.; Chah, K.F.; Torres, C. Antimicrobial resistance in Escherichia coli isolates from frugivorous (Eidolon helvum) and insectivorous (Nycteris hispida) bats in Southeast Nigeria, with detection of CTX-M-15 producing isolates. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 2021, 75, 101613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolejska, M.; Literak, I. Wildlife Is Overlooked in the Epidemiology of Medically Important Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01167-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbehang Nguema, P.P.; Onanga, R.; Ndong Atome, G.R.; Obague Mbeang, J.C.; Mabika Mabika, A.; Yaro, M.; Lounnas, M.; Dumont, Y.; Zohra, Z.F.; Godreuil, S.; et al. Characterization of ESBL-Producing Enterobacteria from Fruit Bats in an Unprotected Area of Makokou, Gabon. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoubangoye, B.; Fouchet, D.; Boundenga, L.A.; Cassan, C.; Arnathau, C.; Meugnier, H.; Tsoumbou, T.-A.; Dibakou, S.E.; Otsaghe Ekore, D.; Nguema, Y.O.; et al. Staphylococcus aureus Host Spectrum Correlates with Methicillin Resistance in a Multi-Species Ecosystem. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munk, P.; Brinch, C.; Møller, F.D.; Petersen, T.N.; Hendriksen, R.S.; Seyfarth, A.M.; Kjeldgaard, J.S.; Svendsen, C.A.; van Bunnik, B.; Berglund, F.; et al. Genomic analysis of sewage from 101 countries reveals global landscape of antimicrobial resistance. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 7251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, H.K.; Donato, J.; Wang, H.H.; Cloud-Hansen, K.A.; Davies, J.; Handelsman, J. Call of the wild: Antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2010, 8, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijbers, P.M.C.; Blaak, H.; de Jong, M.C.M.; Graat, E.A.M.; Vandenbroucke-Grauls, C.M.J.E.; de Roda Husman, A.M. Role of the Environment in the Transmission of Antimicrobial Resistance to Humans: A Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 11993–12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgin, C.J.; Colella, J.P.; Kahn, P.L.; Upham, N.S. How many species of mammals are there? J. Mammal. 2018, 99, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, N.B.; Cirranello, A.L. Bat Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Database. 2024. Available online: https://batnames.org (accessed on 4 April 2022).

- Devnath, P.; Karah, N.; Graham, J.P.; Rose, E.S.; Asaduzzaman, M. Evidence of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bats and Its Planetary Health Impact for Surveillance of Zoonotic Spillover Events: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaru, I.D.; Walther, B.; Schaumburg, F. Zoonotic sources and the spread of antimicrobial resistance from the perspective of low and middle-income countries. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2023, 12, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcock, B.P.; Huynh, W.; Chalil, R.; Smith, K.W.; Raphenya, A.R.; Wlodarski, M.A.; Edalatmand, A.; Petkau, A.; Syed, S.A.; Tsang, K.K.; et al. CARD 2023: Expanded curation, support for machine learning, and resistome prediction at the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D690–D699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltoumas, F.A.; Karatzas, E.; Paez-Espino, D.; Venetsianou, N.K.; Aplakidou, E.; Oulas, A.; Finn, R.D.; Ovchinnikov, S.; Pafilis, E.; Kyrpides, N.C.; et al. Exploring microbial functional biodiversity at the protein family level—From metagenomic sequence reads to annotated protein clusters. Front. Bioinform. 2023, 3, 1157956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar-Zepeda, A.; Vera-Ponce de León, A.; Sanchez-Flores, A. The Road to Metagenomics: From Microbiology to DNA Sequencing Technologies and Bioinformatics. Front. Genet. 2015, 6, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.-X.; Qin, Y.; Chen, T.; Lu, M.; Qian, X.; Guo, X.; Bai, Y. A practical guide to amplicon and metagenomic analysis of microbiome data. Protein Cell 2021, 12, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, B.P.; Raphenya, A.R.; Lau, T.T.Y.; Tsang, K.K.; Bouchard, M.; Edalatmand, A.; Huynh, W.; Nguyen, A.-L.V.; Cheng, A.A.; Liu, S.; et al. CARD 2020: Antibiotic resistome surveillance with the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D517–D525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, P.T.L.C.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Lund, O. Rapid and precise alignment of raw reads against redundant databases with KMA. BMC Bioinform. 2018, 19, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bortolaia, V.; Kaas, R.S.; Ruppe, E.; Roberts, M.C.; Schwarz, S.; Cattoir, V.; Philippon, A.; Allesoe, R.L.; Rebelo, A.R.; Florensa, A.F.; et al. ResFinder 4.0 for predictions of phenotypes from genotypes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2020, 75, 3491–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, D. Homology. In Encyclopedia of Astrobiology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 760–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicoludis, J.M.; Gaudet, R. Applications of sequence coevolution in membrane protein biochemistry. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr 2018, 1860, 895–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, A.G.; Elhabashy, H.; Brock, K.P.; Maddamsetti, R.; Kohlbacher, O.; Marks, D.S. Large-scale discovery of protein interactions at residue resolution using co-evolution calculated from genomic sequences. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altschuh, D.; Lesk, A.M.; Bloomer, A.C.; Klug, A. Correlation of co-ordinated amino acid substitutions with function in viruses related to tobacco mosaic virus. J. Mol. Biol. 1987, 193, 693–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chivian, D.; Dehal, P.S.; Keller, K.; Arkin, A.P. metaMicrobesOnline: Phylogenomic analysis of microbial communities. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 41, D648–D654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kembel, S.W.; Eisen, J.A.; Pollard, K.S.; Green, J.L. The Phylogenetic Diversity of Metagenomes. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revilla-Martín, N.; Alonso-Alonso, P.; Sereno-Cadierno, J.; Llanos-Guerrero, C.; Hernández-Tabernero, L.; Lizana-Avia, M. Bat conservation and ecotourism: The case of two abandoned tunnels in Salamanca, Western Iberia. Barbastella 2021, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, J.M.; Soto López, J.D.; Lizana-Ciudad, D.; Fernández-Soto, P.; Muro, A. Molecular Detection of Histoplasma in Bat-Inhabited Tunnels of Camino de Hierro Tourist Route, Spain. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2025, 31, 1010–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-López, J.D.; García-Martín, J.M.; Lizana-Ciudad, D.; Lizana, M.; Hernández-Tabernero, L.; Fernández-Soto, P.; Velásquez-González, O.E.; Aragón, S.L.; Belhassen-García, M.; Muro, A.; et al. Taxonomic and functional profiling of bat guano microbiota from hiking trail-associated tunnels: A potential risk for human health? Environ. Microbiome 2025, 20, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abraham, T.; Yazdi, Z.; Littman, E.; Shahin, K.; Heckman, T.I.; Quijano Cardé, E.M.; Nguyen, D.T.; Hu, R.; Adkison, M.; Veek, T.; et al. Detection and virulence of Lactococcus garvieae and L. petauri from four lakes in southern California. J. Aquat. Anim. Health 2023, 35, 187–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Bravo, A.; Figueras, M.J. An Update on the Genus Aeromonas: Taxonomy, Epidemiology, and Pathogenicity. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, I. Dysgonomonas. In Bergey’s Manual of Systematics of Archaea and Bacteria; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.P.; Monchy, S.; Cardinale, M.; Taghavi, S.; Crossman, L.; Avison, M.B.; Berg, G.; van der Lelie, D.; Dow, J.M. The versatility and adaptation of bacteria from the genus Stenotrophomonas. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 514–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyothsna, T.S.S.; Tushar, L.; Sasikala, C.; Ramana, C.V. Paraclostridium benzoelyticum gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from marine sediment and reclassification of Clostridium bifermentans as Paraclostridium bifermentans comb. nov. Proposal of a new genus Paeniclostridium gen. nov. to accommodate Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium ghonii. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2016, 66, 1268–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín, I.; Arahal, D.R. The Family Beijerinckiaceae. In The Prokaryotes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühldorfer, K.; Speck, S.; Wibbelt, G. Proposal of Vespertiliibacter pulmonis gen. nov., sp. nov. and two genomospecies as new members of the family Pasteurellaceae isolated from European bats. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2014, 64, 2424–2430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, G.C.; Budge, G.E.; Frost, C.L.; Neumann, P.; Siozios, S.; Yañez, O.; Hurst, G.D. Transitions in symbiosis: Evidence for environmental acquisition and social transmission within a clade of heritable symbionts. ISME J. 2021, 15, 2956–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morni, M.A.; William-Dee, J.; Jinggong, E.R.; Al-Shuhada Sabaruddin, N.; Azhar, N.A.A.; Iman, M.A.; Larsen, P.A.; Seelan, J.S.S.; Bilung, L.M.; Khan, F.A.A. Gut microbiome community profiling of Bornean bats with different feeding guilds. Anim. Microbiome 2025, 7, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayman, D.T.S.; Bowen, R.A.; Cryan, P.M.; McCracken, G.F.; O’Shea, T.J.; Peel, A.J.; Gilbert, A.; Webb, C.T.; Wood, J.L.N. Ecology of Zoonotic Infectious Diseases in Bats: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Zoonoses Public Health 2013, 60, 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, J.; Guo, W.; Chen, M.; Xue, L.; Wang, J.; Ma, L. Prevalence and Genetic Diversity of Enterococcus faecalis Isolates from Mineral Water and Spring Water in China. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bélanger, L.; Garenaux, A.; Harel, J.; Boulianne, M.; Nadeau, E.; Dozois, C.M. Escherichia coli from animal reservoirs as a potential source of human extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 62, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oyeka, M.; Antony, S. Citrobacter braakii Bacteremia: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets 2017, 17, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, E.-J.; Goussard, S.; Touchon, M.; Krizova, L.; Cerqueira, G.; Murphy, C.; Lambert, T.; Grillot-Courvalin, C.; Nemec, A.; Courvalin, P. Origin in Acinetobacter guillouiae and Dissemination of the Aminoglycoside-Modifying Enzyme Aph(3′)-VI. mBio 2014, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez-Boland, J.A.; Meijer, W.G. The pathogenic actinobacterium Rhodococcus equi: What’s in a name? Mol. Microbiol. 2019, 112, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkko, P.; Suomalainen, S.; Iivanainen, E.; Tortoli, E.; Suutari, M.; Seppänen, J.; Paulin, L.; Katila, M.-L. Mycobacterium palustre sp. nov., a potentially pathogenic, slowly growing mycobacterium isolated from clinical and veterinary specimens and from Finnish stream waters. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 1519–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, H.C.; Lee, C.Y.Q.; Cheok, Y.Y.; Tan, G.M.Y.; Looi, C.Y.; Wong, W.F. Chlamydiaceae: Diseases in Primary Hosts and Zoonosis. Microorganisms 2019, 7, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangutov, E.O.; Kharseeva, G.G.; Alutina, E.L. Corynebacterium spp.—Problematic pathogens of the human respiratory tract (review of literature). Russ. Clin. Lab. Diagn. 2021, 66, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, D.-W.; Heo, S.; Ryu, S.; Blom, J.; Lee, J.-H. Genomic insights into the virulence and salt tolerance of Staphylococcus equorum. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho, A.; Giambiagi-Demarval, M.; Rossi, C.C. Mammaliicoccus sciuri’s Pan-Immune System and the Dynamics of Horizontal Gene Transfer Among Staphylococcaceae: A One-Health CRISPR Tale. J. Microbiol. 2024, 62, 775–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birlutiu, V.; Birlutiu, R.-M.; Dobritoiu, E.S. Lelliottia amnigena and Pseudomonas putida Coinfection Associated with a Critical SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Case Report. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 2143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Vivas, J. Microbiología de Hafnia alvei. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2020, 38, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, A.; Eder, W.; Fareleira, P.; Santos, H.; Huber, R. Salinisphaera shabanensis gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel, moderately halophilic bacterium from the brine–seawater interface of the Shaban Deep, Red Sea. Extremophiles 2003, 7, 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, M.; Gorlenko, Z.; Mindlin, S. Molecular structure and translocation of a multiple antibiotic resistance region of a Psychrobacter psychrophilus permafrost strain. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 296, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Environmental Protection Agency. National Rivers and Streams Assessment: The Third Collaborative Survey; US Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Poosakkannu, A.; Xu, Y.; Suominen, K.M.; Meierhofer, M.B.; Sørensen, I.H.; Madsen, J.J.; Plaquin, B.; Guillemain, M.; Joyeux, E.; Keišs, O.; et al. Pathogenic bacterial taxa constitute a substantial portion of fecal microbiota in common migratory bats and birds in Europe. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0194824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heir, E.; Sundheim, G.; Holck, A.L. The qacG gene on plasmid pST94 confers resistance to quaternary ammonium compounds in staphylococci isolated from the food industry. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1999, 86, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDougall, F.; Boardman, W.; Gillings, M.; Power, M. Bats as reservoirs of antibiotic resistance determinants: A survey of class 1 integrons in Grey-headed Flying Foxes (Pteropus poliocephalus). Infect. Genet. Evol. 2019, 70, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Fu, J.; Zhao, K.; Yang, S.; Li, C.; Penttinen, P.; Ao, X.; Liu, A.; Hu, K.; Li, J.; et al. Class 1 integron carrying qacEΔ1 gene confers resistance to disinfectant and antibiotics in Salmonella. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 404, 110319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sousa, M.; Machado, I.; Simões, L.C.; Simões, M. Biocides as drivers of antibiotic resistance: A critical review of environmental implications and public health risks. Environ. Sci. Ecotechnol. 2025, 25, 100557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bragg, R.; Jansen, A.; Coetzee, M.; van der Westhuizen, W.; Boucher, C. Bacterial Resistance to Quaternary Ammonium Compounds (QAC) Disinfectants. In Infectious Diseases and Nanomedicine II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, Y.; Tomida, J.; Kawamura, Y. Efflux-mediated fluoroquinolone resistance in the multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolate PA7: Identification of a novel MexS variant involved in upregulation of the mexEF-oprN multidrug efflux operon. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poole, K. Efflux-Mediated Resistance to Fluoroquinolones in Gram-Positive Bacteria and the Mycobacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2595–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Yang, B.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, G.; Yang, J.; Xue, F.; Shao, J.; Yi, X.; Jiang, Y. The Role of AcrAB-TolC Efflux Pump in Mediating Fluoroquinolone Resistance in Naturally Occurring Salmonella Isolates from China. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2017, 14, 728–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cui, C.-Y.; Yu, J.-J.; He, Q.; Wu, X.-T.; He, Y.-Z.; Cui, Z.-H.; Li, C.; Jia, Q.-L.; Shen, X.-G.; et al. Genetic diversity and characteristics of high-level tigecycline resistance Tet(X) in Acinetobacter species. Genome Med. 2020, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, X.-Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wu, H.; Liu, J.; Gu, Q.-Y.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Sun, L.; Jiao, X.; Li, Q.; Wang, J. Distribution and spread of tigecycline resistance gene tet(X4) in Escherichia coli from different sources. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 14, 1399732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitz, F.-J.; Fluit, A.C. Mechanisms of antibacterial resistance. In Infectious Diseases; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 1308–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.-Z.; Yoshida, T.; Fujiwara, A.; Nishiki, I. Characterization of lsa (D), a Novel Gene Responsible for Resistance to Lincosamides, Streptogramins A, and Pleuromutilins in Fish Pathogenic Lactococcus garvieae Serotype II. Microb. Drug Resist. 2021, 27, 301–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, S.; Shen, J.; Kadlec, K.; Wang, Y.; Brenner Michael, G.; Feßler, A.T.; Vester, B. Lincosamides, Streptogramins, Phenicols, and Pleuromutilins: Mode of Action and Mechanisms of Resistance. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2016, 6, a027037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agustin, A.L.D.; Khairullah, A.R.; Effendi, M.H.; Tyasningsih, W.; Moses, I.B.; Budiastuti, B.; Plumeriastuti, H.; Yanestria, S.M.; Riwu, K.H.P.; Dameanti, F.N.A.E.P.; et al. Ecological and public health dimensions of ESBL-producing Escherichia coli in bats: A One Health perspective. Veter-World 2025, 18, 1199–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, W.; Kumar, V.; Ding, Y.; Ero, R.; Serra, A.; Lee, B.S.T.; Wong, A.S.W.; Shi, J.; Sze, S.W.; Yang, L.; et al. Ribosome protection by antibiotic resistance ATP-binding cassette protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, 5157–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, A.; Gaballa, A.; Yang, H.; Yu, D.; Ernst, R.K.; Wiedmann, M. Site-selective modifications by lipid A phosphoethanolamine transferases linked to colistin resistance and bacterial fitness. mSphere 2024, 9, e0073124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Vuillemin, X.; Kieffer, N.; Mueller, L.; Descombes, M.-C.; Nordmann, P. Identification of FosA8, a Plasmid-Encoded Fosfomycin Resistance Determinant from Escherichia coli, and Its Origin in Leclercia adecarboxylata. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittle, G.; Whitehead, T.R.; Hamburger, N.; Shoemaker, N.B.; Cotta, M.A.; Salyers, A.A. Identification of a New Ribosomal Protection Type of Tetracycline Resistance Gene, tet (36), from Swine Manure Pits. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 4151–4158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.V.D.; Furtado, R.M.; da Costa, K.S.; Vakal, S.; Lima, A.H. Advances in UDP-N-Acetylglucosamine Enolpyruvyl Transferase (MurA) Covalent Inhibition. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 889825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tooke, C.L.; Hinchliffe, P.; Bragginton, E.C.; Colenso, C.K.; Hirvonen, V.H.A.; Takebayashi, Y.; Spencer, J. β-Lactamases and β-Lactamase Inhibitors in the 21st Century. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 3472–3500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, I.V.; Manakhov, A.D.; Gorobets, V.E.; Diakova, K.B.; Lukbanova, E.A.; Malinovkin, A.V.; Venema, K.; Ermakov, A.M.; Popov, I.V. Metagenomic Investigation of Intestinal Microbiota of Insectivorous Synanthropic Bats: Densoviruses, Antibiotic Resistance Genes, and Functional Profiling of Gut Microbial Communities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDougall, F.K.; Boardman, W.S.J.; Power, M.L. Characterization of beta-lactam-resistant Escherichia coli from Australian fruit bats indicates anthropogenic origins. Microb. Genom. 2021, 7, 000571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrupación Europea de Cooperación Territorial Duero-Douro. Manual de la Biodiversidad Autóctona; Imprenta Catedra: Salamanca, Spain, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kosznik-Kwaśnicka, K.; Golec, P.; Jaroszewicz, W.; Lubomska, D.; Piechowicz, L. Into the Unknown: Microbial Communities in Caves, Their Role, and Potential Use. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Xie, S.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; He, X.; Luo, P.; Deng, J.; Zhou, C.; Qin, J.; Huang, C.; et al. The difference in the composition of gut microbiota is greater among bats of different phylogenies than among those with different dietary habits. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1207482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, W.; Li, M.; Huang, C.; Wei, A. Quantifying Live Aboveground Biomass and Forest Disturbance of Mountainous Natural and Plantation Forests in Northern Guangdong, China, Based on Multi-Temporal Landsat, PALSAR and Field Plot Data. Remote Sens. 2016, 8, 595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Mo, J.; Lu, X.; Xue, J.; Li, J.; Fang, Y. Effects of elevated nitrogen deposition on soil microbial biomass carbon in major subtropical forests of southern China. Front. For. China 2009, 4, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Li, M.; Huang, C.; Tao, X.; Li, S.; Wei, A. Mapping Annual Forest Change Due to Afforestation in Guangdong Province of China Using Active and Passive Remote Sensing Data. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Leary, N.A.; Cox, E.; Holmes, J.B.; Anderson, W.R.; Falk, R.; Hem, V.; Tsuchiya, M.T.N.; Schuler, G.D.; Zhang, X.; Torcivia, J.; et al. Exploring and retrieving sequence and metadata for species across the tree of life with NCBI Datasets. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmead, B.; Salzberg, S.L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 357–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langmead, B.; Wilks, C.; Antonescu, V.; Charles, R. Scaling read aligners to hundreds of threads on general-purpose processors. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, F. Trim Galore. 2021. Available online: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/trim_galore/ (accessed on 12 Octorber 2025).

- Chen, S. Ultrafast one-pass FASTQ data preprocessing, quality control, and deduplication using fastp. iMeta 2023, 2, e107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, S. FastQC: A Quality Control Tool for High Throughput Sequence Data [Online]. 2010. Available online: http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (accessed on 4 May 2022).

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An ultra-fast single-node solution for large and complex metagenomics assembly via succinct de Bruijn graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Sipos, B.; Zhao, L. SeqKit2: A Swiss army knife for sequence and alignment processing. iMeta 2024, 3, e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bushnell, B. BBMap: A Fast, Accurate, Splice-Aware Aligner. 2014. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:114702182 (accessed on 12 Octorber 2025).

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes De Novo Assembler. Curr. Protoc. Bioinform. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danecek, P.; Bonfield, J.K.; Liddle, J.; Marshall, J.; Ohan, V.; Pollard, M.O.; Whitwham, A.; Keane, T.; McCarthy, S.A.; Davies, R.M.; et al. Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. GigaScience 2021, 10, giab008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.D.; Li, F.; Kirton, E.; Thomas, A.; Egan, R.; An, H.; Wang, Z. MetaBAT 2: An adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.-W.; Tang, Y.-H.; Tringe, S.G.; Simmons, B.A.; Singer, S.W. MaxBin: An automated binning method to recover individual genomes from metagenomes using an expectation-maximization algorithm. Microbiome 2014, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alneberg, J.; Bjarnason, B.S.; de Bruijn, I.; Schirmer, M.; Quick, J.; Ijaz, U.Z.; Lahti, L.; Loman, N.J.; Andersson, A.F.; Quince, C. Binning metagenomic contigs by coverage and composition. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 1144–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sieber, C.M.K.; Probst, A.J.; Sharrar, A.; Thomas, B.C.; Hess, M.; Tringe, S.G.; Banfield, J.F. Recovery of genomes from metagenomes via a dereplication, aggregation and scoring strategy. Nat. Microbiol. 2018, 3, 836–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chklovski, A.; Parks, D.H.; Woodcroft, B.J.; Tyson, G.W. CheckM2: A rapid, scalable and accurate tool for assessing microbial genome quality using machine learning. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1203–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manni, M.; Berkeley, M.R.; Seppey, M.; Zdobnov, E.M. BUSCO: Assessing Genomic Data Quality and Beyond. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwengers, O.; Jelonek, L.; Dieckmann, M.A.; Beyvers, S.; Blom, J.; Goesmann, A. Bakta: Rapid and standardized annotation of bacterial genomes via alignment-free sequence identification. Microb. Genom. 2021, 7, 000685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT Multiple Sequence Alignment Software Version 7: Improvements in Performance and Usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Sun, S.; Sun, N.; Lu, L.; Zhang, C.; Shi, W.; Zhao, Y.; Jia, S. HMMER-Extractor: An auxiliary toolkit for identifying genomic macromolecular metabolites based on Hidden Markov Models. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 283, 137666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capella-Gutiérrez, S.; Silla-Martínez, J.M.; Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1972–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, T.; Ly-Trong, N.; Ren, H.; Baños, H.; Roger, A.; Susko, E.; Bielow, C.; De Maio, N.; Goldman, N.; Hahn, M.W.; et al. IQ-TREE 3: Phylogenomic Inference Software using Complex Evolutionary Models. IQ-TREE 3 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Chernomor, O.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q.; Vinh, L.S. UFBoot2: Improving the Ultrafast Bootstrap Approximation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2018, 35, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: Rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaumeil, P.-A.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Parks, D.H. GTDB-Tk v2: Memory friendly classification with the genome taxonomy database. Bioinformatics 2022, 38, 5315–5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arkin, A.P.; Cottingham, R.W.; Henry, C.S.; Harris, N.L.; Stevens, R.L.; Maslov, S.; Dehal, P.; Ware, D.; Perez, F.; Canon, S.; et al. KBase: The United States Department of Energy Systems Biology Knowledgebase. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 566–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G. Data Integration, Manipulation and Visualization of Phylogenetic Trees; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Core Team: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation. 2014. Available online: https://dplyr.tidyverse.org/ (accessed on 12 Octorber 2025).

- Wickham, H.; Vaughan, D.; Girlich, M. tidyr: Tidy Messy Data. 2014. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/tidyr/index.html (accessed on 12 Octorber 2025).

- Oksanen, J.; Simpson, G.L.; Blanchet, F.G.; Kindt, R.; Legendre, P.; Minchin, P.R.; O’Hara, R.B.; Solymos, P.; Stevens, M.H.H.; Szoecs, E.; et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2001. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/vegan/vegan.pdf (accessed on 12 Octorber 2025).

- De Cáceres, M.; Legendre, P. Associations between species and groups of sites: Indices and statistical inference. Ecology 2009, 90, 3566–3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014, 15, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, A.; Ibrahim, J.G.; Love, M.I. Heavy-tailed prior distributions for sequence count data: Removing the noise and preserving large differences. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 2084–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Soto-López, J.D.; Velásquez-González, O.; Barrios-Izás, M.A.; Belhassen-García, M.; Muñoz-Bellido, J.L.; Fernández-Soto, P.; Muro, A. Metagenomic Comparison of Bat Colony Resistomes Across Anthropogenic and Pristine Habitats. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010051

Soto-López JD, Velásquez-González O, Barrios-Izás MA, Belhassen-García M, Muñoz-Bellido JL, Fernández-Soto P, Muro A. Metagenomic Comparison of Bat Colony Resistomes Across Anthropogenic and Pristine Habitats. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleSoto-López, Julio David, Omar Velásquez-González, Manuel A. Barrios-Izás, Moncef Belhassen-García, Juan Luis Muñoz-Bellido, Pedro Fernández-Soto, and Antonio Muro. 2026. "Metagenomic Comparison of Bat Colony Resistomes Across Anthropogenic and Pristine Habitats" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010051

APA StyleSoto-López, J. D., Velásquez-González, O., Barrios-Izás, M. A., Belhassen-García, M., Muñoz-Bellido, J. L., Fernández-Soto, P., & Muro, A. (2026). Metagenomic Comparison of Bat Colony Resistomes Across Anthropogenic and Pristine Habitats. Antibiotics, 15(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010051