First Multi-Facility Antimicrobial Surveillance in Japanese Hospital Wastewater Reveals Spatiotemporal Trends and Source-Specific Environmental Loads

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

2.2. Survey of Hospital Wastewater at Multiple Facilities in Urban Area of Japan

2.3. Analytical Procedures for Antimicrobials in the Wastewater Based on the High-Throughput Analysis

2.4. Method Validation

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

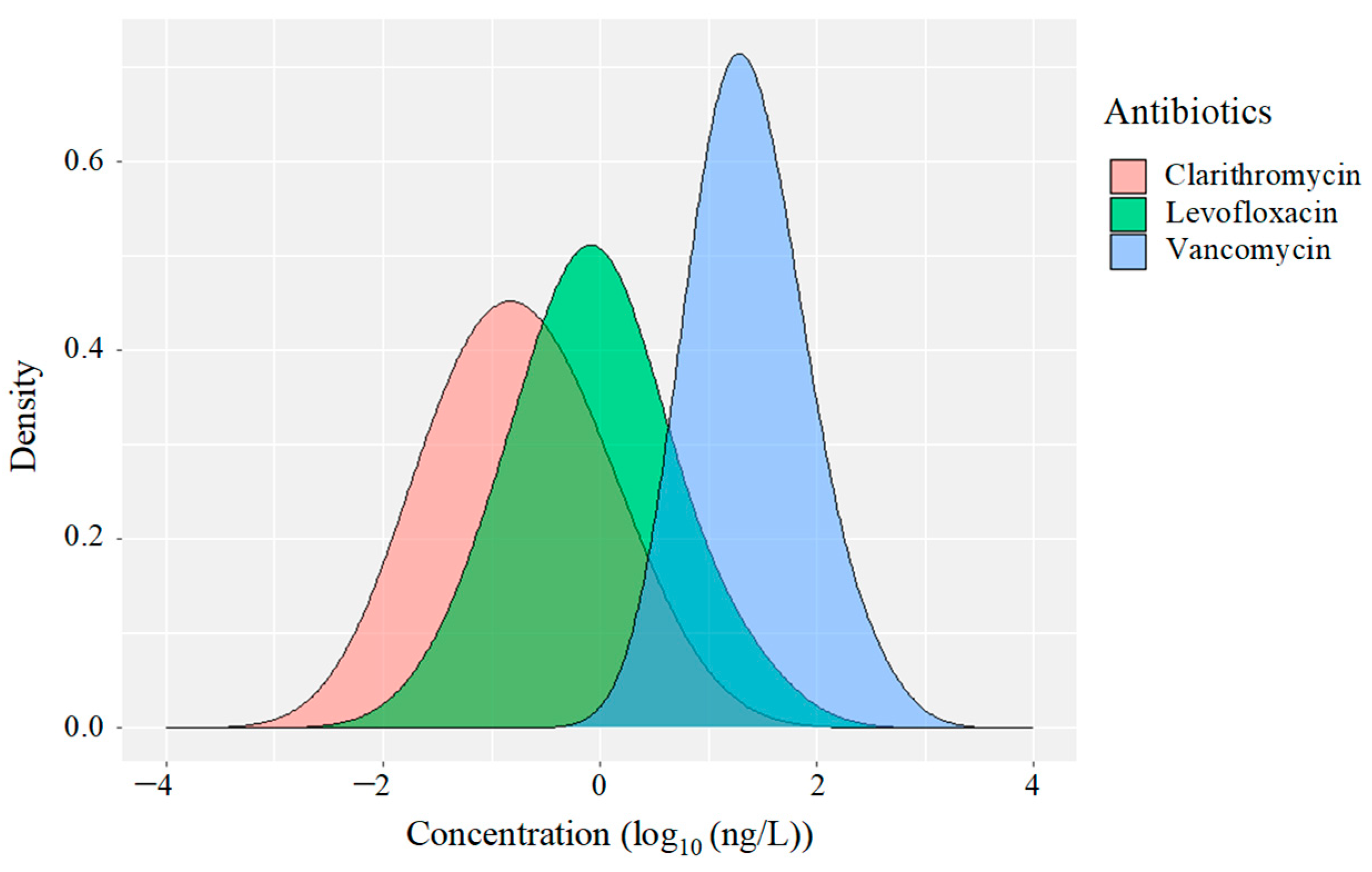

3.1. Distribution of Antimicrobial Concentrations in Wastewater from Hospitals and a Commercial Facility

3.1.1. β-Lactams

3.1.2. New Quinolones

3.1.3. Macrolides

3.1.4. Tetracyclines

3.1.5. Glycopeptide

3.2. Temporal Dynamics of Antimicrobials in Hospital Wastewater

3.2.1. β-Lactams

3.2.2. New Quinolones

3.2.3. Macrolides

3.2.4. Tetracyclines

3.2.5. Glycopeptide

3.3. Temporal Variations and Distribution Patterns of Antimicrobials in Hospital and Commercial Wastewaters

4. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Albarano, L.; Padilla Suarez, E.G.; Maggio, C.; La Marca, A.; Iovine, R.; Lofrano, G.; Guida, M.; Vaiano, V.; Carotenuto, M.; Libralato, G. Assessment of ecological risks posed by veterinary antibiotics in european aquatic environments: A comprehensive review and analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 954, 176280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouabadi, I.; Miyah, Y.; Benjelloun, M.; El-habacha, M.; El Addouli, J. Advanced strategies for the innovative treatment of hospital liquid effluents: A comprehensive review. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2024, 28, 101990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, J.; Lai, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Li, B. Transfer dynamics of intracellular and extracellular last-resort antibiotic resistome in hospital wastewater. Water Res. 2025, 283, 123833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mejías, C.; Martín-Pozo, L.; Santos, J.L.; Martín, J.; Aparicio, I.; Alonso, E. Occurrence, dissipation kinetics and environmental risk assessment of antibiotics and their metabolites in agricultural soils. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 479, 135586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, G.; Ma, B.; Musat, N.; Shen, P.; Wei, Z.; Wei, Y.; Richnow, H.H.; Zhang, J. Deciphering the transfer of antimicrobial resistance genes in the urban water cycle from water source to reuse: A review. Environ. Int. 2025, 201, 109584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Huang, X.; Xie, Z.; Ding, Z.; Wei, H.; Jin, Q. A review focusing on mechanisms and ecological risks of enrichment and propagation of antibiotic resistance genes and mobile genetic elements by microplastic biofilms. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heida, A.; Hamilton, M.T.; Gambino, J.; Sanderson, K.; Schoen, M.E.; Jahne, M.A.; Garland, J.; Ramirez, L.; Quon, H.; Lopatkin, A.J.; et al. Population ecology-quantitative microbial risk assessment (QMRA) model for antibiotic-resistant and susceptible E. coli in recreational water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 4266–4281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedeño-Muñoz, J.S.; Aransiola, S.A.; Reddy, K.V.; Ranjit, P.; Victor-Ekwebelem, M.O.; Oyedele, O.J.; Pérez-Almeida, I.B.; Maddela, N.R.; Rodríguez-Díaz, J.M. Antibiotic resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes as contaminants of emerging concern: Occurrences, impacts, mitigations and future guidelines. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 952, 175906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastor-López, E.J.; Escolà, M.; Kisielius, V.; Arias, C.A.; Carvalho, P.N.; Gorito, A.M.; Ramos, S.; Freitas, V.; Guimarães, L.; Almeida, C.M.R.; et al. Potential of nature-based solutions to reduce antibiotics, antimicrobial resistance, and pathogens in aquatic ecosystems. A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibodeau, A.J.; Barret, M.; Mouchet, F.; Nguyen, V.X.; Pinelli, E. The potential contribution of aquatic wildlife to antibiotic resistance dissemination in freshwater ecosystems: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 350, 123894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganthavee, V.; Trzcinski, A.P. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for the optimization of pharmaceutical wastewater treatment systems: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2024, 22, 2293–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, N.; Foster, T.; Shimki, N.T.; Willetts, J. Hospital wastewater (HWW) treatment in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of microbial treatment efficacy. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 921, 170994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Cheng, Z.; Huang, B.; Mao, Y.; Hu, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Wang, M.; Huang, S.; Han, M. Deciphering the profiles and hosts of antibiotic resistance genes and evaluating the risk assessment of general and non-general hospital wastewater by metagenomic sequencing. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 375, 126313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Xu, Z.; Dong, B. Occurrence, fate, and ecological risk of antibiotics in wastewater treatment plants in china: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 469, 133925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shuai, X.; Zhou, Z.; Zhu, L.; Achi, C.; Lin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Yu, X.; Zhou, J.; Lin, Y.; Chen, H. Ranking the risk of antibiotic resistance genes by metagenomic and multifactorial analysis in hospital wastewater systems. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 468, 133790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Martín, P.A.; Schinkel, L.; Eberhard, Y.; Giger, W.; Berg, M.; Hollender, J. Suspect and nontarget screening of organic micropollutants in swiss sewage sludge: A nationwide survey. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 7688–7698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Zheng, Q.; Thai, P.K.; Ahmed, F.; O’Brien, J.W.; Mueller, J.F.; Thomas, K.V.; Tscharke, B. A nationwide wastewater-based assessment of metformin consumption across Australia. Environ. Int. 2022, 165, 107282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance 1990–2021: A systematic analysis with forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, T.; Katagiri, M.; Sasaki, N.; Kuroda, M.; Watanabe, M. Performance of a pilot-scale continuous flow ozone-based hospital wastewater treatment system. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xu, S.; Zhao, K.; Song, G.; Zhao, S.; Liu, R. Risk control of antibiotics, antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) and antibiotic resistant bacteria (ARB) during sewage sludge treatment and disposal: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 877, 162772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, Japan. Japan Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (JANIS), Nosocomial Infections Surveillance for Antimicrobial-Resistant Bacteria. Available online: https://janis.mhlw.go.jp/english/index.asp (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare, Japan. Annual Report on Statistics of Production by Pharmaceutical Industry in 2024. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/list/105-1.html (accessed on 15 December 2025). (In Japanese)

- Azuma, T.; Matsunaga, N.; Ohmagari, N.; Kuroda, M. Development of a high-throughput analytical method for antimicrobials in wastewater using an automated pipetting and solid-phase extraction system. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keely, S.P.; Brinkman, N.E.; Wheaton, E.A.; Jahne, M.A.; Siefring, S.D.; Varma, M.; Hill, R.A.; Leibowitz, S.G.; Martin, R.W.; Garland, J.L.; et al. Geospatial patterns of antimicrobial resistance genes in the US EPA national rivers and streams assessment survey. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 14960–14971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, L.; Lee, D.; Cho, H.K.; Choi, S.D. Review of the quechers method for the analysis of organic pollutants: Persistent organic pollutants, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and pharmaceuticals. Trends Environ. Anal. Chem. 2019, 22, e00063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, M.; Tang, S.; Bao, Y.; Daniels, K.D.; How, Z.T.; El-Din, M.G.; Wang, J.; Tang, L. Fully-automated spe coupled to UHPLC-MS/MS method for multiresidue analysis of 26 trace antibiotics in environmental waters: SPE optimization and method validation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 16973–16987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Sui, Q.; Yu, X.; Zhao, W.; Li, Q.; Fatta-Kassinos, D.; Lyu, S. Identification of indicator ppcps in landfill leachates and livestock wastewaters using multi-residue analysis of 70 PPCPs: Analytical method development and application in yangtze river delta, china. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 753, 141653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ge, S.; Shao, P.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Wei, W.; He, C.; Zhang, L. Occurrence and removal rate of typical pharmaceuticals and personal care products (PPCPs) in an urban wastewater treatment plant in Beijing, China. Chemosphere 2023, 339, 139644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, M.E.; Farkas, K.; Wade, M.; Webster, G.; Pass, D.A.; Perry, W.; Kille, P.; Singer, A.; Jones, D.L. Wastewater-based analysis of antimicrobial resistance at uk airports: Evaluating the potential opportunities and challenges. Environ. Int. 2025, 195, 109260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Pei, Y.; Qu, M.; Lv, P.; Zhang, J.; Xu, X.; Hu, Y.; Wang, Y. Deciphering antibiotic resistance genes and plasmids in pathogenic bacteria from 166 hospital effluents in Shanghai, China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 483, 136641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, L.Y.; Lin, H.; Wu, X.Y.; Bi, W.J.; Wang, L.T.; Mao, D.Q.; Luo, Y. The prevalence of ampicillin-resistant opportunistic pathogenic bacteria undergoing selective stress of heavy metal pollutants in the Xiangjiang River, China. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, P.; Saha, R.; Halder, G. Towards sorptive eradication of pharmaceutical micro-pollutant ciprofloxacin from aquatic environment: A comprehensive review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 919, 170723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fish, D.N.; Chow, A.T. The clinical pharmacokinetics of levofloxacin. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1997, 32, 101–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izadi, E.; Afshan, G.; Patel, R.P.; Rao, V.M.; Liew, K.B.; Meor Mohd Affandi, M.M.R.; Kifli, N.; Suleiman, A.; Lee, K.S.; Sarker, M.M.R.; et al. Levofloxacin: Insights into antibiotic resistance and product quality. Front. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Q.; Sui, M.; Qin, C.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Y.; Luo, S.; Zhao, J. Migration, transformation and removal of macrolide antibiotics in the environment: A review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 26045–26062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amsden, G.W. Erythromycin, clarithromycin, and azithromycin: Are the differences real? Clin. Ther. 1996, 18, 56–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zillien, C.; Groenveld, T.; Schut, O.; Beeltje, H.; Blanco-Ania, D.; Posthuma, L.; Roex, E.; Ragas, A. Assessing city-wide pharmaceutical emissions to wastewater via modelling and passive sampling. Environ. Int. 2024, 185, 108524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moja, L.; Zanichelli, V.; Mertz, D.; Gandra, S.; Cappello, B.; Cooke, G.S.; Chuki, P.; Harbarth, S.; Pulcini, C.; Mendelson, M.; et al. Who’s essential medicines and aware: Recommendations on first- and second-choice antibiotics for empiric treatment of clinical infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, S1–S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, M.J. The pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic properties of vancomycin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 42, S35–S39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Toole, R.F.; Leong, K.W.C.; Cumming, V.; Van Hal, S.J. Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium and the emergence of new sequence types associated with hospital infection. Res. Microbiol. 2023, 174, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansima, M.A.C.K.; Zvomuya, F.; Amarakoon, I. Fate of veterinary antimicrobials in Canadian prairie soils—A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 892, 164387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, T.; Otomo, K.; Kunitou, M.; Shimizu, M.; Hosomaru, K.; Mikata, S.; Ishida, M.; Hisamatsu, K.; Yunoki, A.; Mino, Y.; et al. Environmental fate of pharmaceutical compounds and antimicrobial-resistant bacteria in hospital effluents, and contributions to pollutant loads in the surface waters in japan. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 657, 476–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, W.L.; Song, C.; He, L.Y.; Wang, B.; Gao, F.Z.; Zhang, M.; Ying, G.G. Antibiotics in soil and water: Occurrence, fate, and risk. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2023, 32, 100437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusandu, A.; Bustadmo, L.; Gravvold, H.; Anvik, M.S.; Skilleås Olsen, K.; Hanger, N. Iodinated contrast media waste management in hospitals in central Norway. Radiography 2024, 30, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Wang, L.; Pang, K.; Ma, S.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, R.; Xia, X. Source orientation, environmental fate, and risks of antibiotics in the surface water of the largest sediment-laden river. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 375, 126363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bijlsma, L.; Pitarch, E.; Fonseca, E.; Ibáñez, M.; Botero, A.M.; Claros, J.; Pastor, L.; Hernández, F. Investigation of pharmaceuticals in a conventional wastewater treatment plant: Removal efficiency, seasonal variation and impact of a nearby hospital. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 105548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, G. Monitoring and analysis of total tetracyclines in water from different environmental scenarios using a designed broad-spectrum aptamer. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 5736–5746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, J.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C.; Lu, Y.; Wang, H.; Dong, Q. Analysis of the effects, existing problems and flexible management suggestions in hospital wastewater treatment: A systematic perspective. J. Water Process Eng. 2025, 72, 107565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sta Ana, K.M.; Madriaga, J.; Espino, M.P. β-lactam antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in Asian lakes and rivers: An overview of contamination, sources and detection methods. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 275, 116624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telgmann, L.; Horn, H. The behavior of pharmaceutically active compounds and contrast agents during wastewater treatment—Combining sampling strategies and analytical techniques: A critical review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M.A.; Nath, N.D.; Johnston, T.V.; Haruna, S.; Ahn, J.; Ovissipour, R.; Ku, S. Harnessing biotechnology for penicillin production: Opportunities and environmental considerations. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 946, 174236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurmessa, B.; Pedretti, E.F.; Cocco, S.; Cardelli, V.; Corti, G. Manure anaerobic digestion effects and the role of pre- and post-treatments on veterinary antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes removal efficiency. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, M.A.A.; Shin, W.S.; Septian, A.; Samaraweera, H.; Khan, I.J.; Mohamed, M.M.; Billah, M.M.; López-Maldonado, E.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; et al. Exploring the environmental pathways and challenges of fluoroquinolone antibiotics: A state-of-the-art review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 926, 171944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, W.; Liu, K.; Guo, Y.; Ding, C.; Han, J.; Li, P. Global review of macrolide antibiotics in the aquatic environment: Sources, occurrence, fate, ecotoxicity, and risk assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 439, 129628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keer, A.; Oza, Y.; Mongad, D.; Ramakrishnan, D.; Dhotre, D.; Ahmed, A.; Zumla, A.; Shouche, Y.; Sharma, A. Assessment of seasonal variations in antibiotic resistance genes and microbial communities in sewage treatment plants for public health monitoring. Environ. Pollut. 2025, 375, 126367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Li, X.; Li, S.; Du, W.; Yan, W.; Xu, H. Degradation of antibiotics by electrochemical oxidation: Current issues, environmental risks, and future strategies. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 516, 163941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Song, Y.; Ling, C.; Shen, Y.; Zhan, X.; Xing, B. Fate of emerging antibiotics in soil-plant systems: A case on fluoroquinolones. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girijan, S.K.; Paul, R.; VJ, R.K.; Pillai, D. Investigating the impact of hospital antibiotic usage on aquatic environment and aquaculture systems: A molecular study of quinolone resistance in Escherichia coli. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 748, 141538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Bou, L.; Gonzalez-Martinez, A.; Gonzalez-Lopez, J.; Correa-Galeote, D. Promising bioprocesses for the efficient removal of antibiotics and antibiotic-resistance genes from urban and hospital wastewaters: Potentialities of aerobic granular systems. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 342, 123115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dželalija, M.; Kvesić, M.; Novak, A.; Fredotović, Ž.; Kalinić, H.; Šamanić, I.; Ordulj, M.; Jozić, S.; Goić Barišić, I.; Tonkić, M.; et al. Microbiome profiling and characterization of virulent and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium from treated and untreated wastewater, beach water and clinical sources. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krul, D.; Negoseki, B.R.d.S.; Siqueira, A.C.; Tomaz, A.P.D.O.; dos Santos, É.M.; de Sousa, I.; Vasconcelos, T.M.; Marinho, I.C.R.; Arend, L.N.V.S.; Mesa, D.; et al. Spread of antimicrobial-resistant clones of the eskapee group: From the clinical setting to hospital effluent. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 973, 179124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, T.; Nakano, T.; Koizumi, R.; Matsunaga, N.; Ohmagari, N.; Hayashi, T. Evaluation of the correspondence between the concentration of antimicrobials entering sewage treatment plant influent and the predicted concentration of antimicrobials using annual sales, shipping, and prescriptions data. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoondert, R.P.J.; Emke, E.; Nagelkerke, E.; Roex, E.; ter Laak, T.L. Impact of reduced sampling frequency of illicit drug wastewater monitoring in the netherlands. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 953, 175767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Digaletos, M.; Ptacek, C.J.; Thomas, J.L. Active and passive sampling techniques in headwater streams to characterize acesulfame-K, pharmaceutical and phosphorus contamination from on-site wastewater disposal systems in canadian rural hamlets. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 956, 177194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zheng, Y.; Yang, H.; Cao, W. How far do we still need to go with antibiotics in aquatic environments? Antibiotic occurrence, chemical-free or chemical-limited strategies, key challenges, and future perspectives. Water Res. 2025, 275, 123179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Innes, G.K.; Patton, A.N.; Prasek, S.M.; Brosky, H.; Khoury, K.; Hodges, T.; Schmitz, B.W. Introduction to wbe case estimation: A practical toolset for public health practitioners. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 980, 179487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boogaerts, T.; Van Wichelen, N.; Quireyns, M.; Burgard, D.; Bijlsma, L.; Delputte, P.; Gys, C.; Covaci, A.; van Nuijs, A.L.N. Current state and future perspectives on de facto population markers for normalization in wastewater-based epidemiology: A systematic literature review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 935, 173223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pant, A.; Shahadat, M.; Ali, S.W.; Ahammad, S.Z. Removal of antimicrobial resistance from secondary treated wastewater—A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 8, 100189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, B.; Yang, S.; Jiao, Z.; Zhang, M.; Yang, Y.; Gao, Y. Advances in environmental pollutant detection techniques: Enhancing public health monitoring and risk assessment. Environ. Int. 2025, 197, 109365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, G.; Chaudhary, P.; Gangola, S.; Gupta, S.; Gupta, A.; Rafatullah, M.; Chen, S. A review on hospital wastewater treatment technologies: Current management practices and future prospects. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 56, 104516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Jin, G.; Cui, R.; Wang, X.; Wang, M.; Chen, Z. Transmission and control strategies of antimicrobial resistance from the environment to the clinic: A holistic review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 957, 177461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrower, J.; McNaughtan, M.; Hunter, C.; Hough, R.; Zhang, Z.; Helwig, K. Chemical fate and partitioning behavior of antibiotics in the aquatic environment—A review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 3275–3298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Dong, Q.; Yuan, Z.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y. Fate characteristics, exposure risk, and control strategy of typical antibiotics in chinese sewerage system: A review. Environ. Int. 2022, 167, 107396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lin, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Meng, F. Antibiotics in mariculture systems: A review of occurrence, environmental behavior, and ecological effects. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 293, 118541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, I.; He, H.; Kinsley, A.C.; Ziemann, S.J.; Degn, L.R.; Nault, A.J.; Beaudoin, A.L.; Singer, R.S.; Wammer, K.H.; Arnold, W.A. Biodegradation, photolysis, and sorption of antibiotics in aquatic environments: A scoping review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 897, 165301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Classification | CAS Registry Number | Antimicrobials | Molecular Formula | Molecular Mass (g/mol) | Structure | pKa | LogP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactams | 69-53-4 | Ampicillin | C16H19N3O4S | 349.4 |  | 2.4 | 1.4 |

| 61-33-6 | Benzylpenicillin | C16H18N2O4S | 334.4 |  | 2.5 | 1.7 | |

| 91832-40-5 | Cefdinir | C14H13N5O5S2 | 395.4 |  | 2.8 | −1.8 | |

| 80210-62-4 | Cefpodoxime | C17H19N5O6S2 | 453.5 |  | 2.8 (Acid) 1.7 (Base) | 0.4 | |

| 87239-81-4 | Cefpodoxime proxetil | C21H27N5O9S2 | 557.6 |  | 8.1 (Acid) 1.7 (Base) | 2.9 | |

| 80370-57-6 | Ceftiofur | C19H17N5O7S3 | 523.6 |  | 2.6 | 1.7 | |

| New quinolones | 85721-33-1 | Ciprofloxacin | C17H18FN3O3 | 331.3 |  | 6.0 | 1.3 |

| 93106-60-6 | Enrofloxacin | C19H22FN3O3 | 359.4 |  | 6.4 | 2.3 | |

| 100986-85-4 | Levofloxacin | C18H20FN3O4 | 361.4 |  | 5.2 | 1.6 | |

| Macrolides | 83905-01-5 | Azithromycin | C38H72N2O12 | 749.0 |  | 13.3 | 3.3 |

| 81103-11-9 | Clarithromycin | C38H69NO13 | 748.0 |  | 13.1 | 3.2 | |

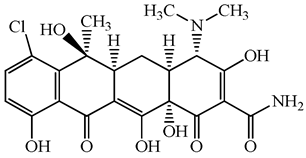

| Tetracyclines | 57-62-5 | Chlortetracycline | C22H23ClN2O8 | 478.9 |  | 4.5 | 4.8 |

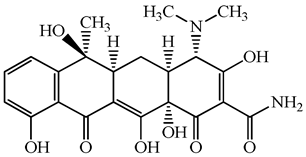

| 564-25-0 | Doxycycline | C22H24N2O8 | 444.4 |  | 4.5 (Acid) 10.8 (Base) | 1.8 | |

| 10118-90-8 | Minocycline | C23H27N3O7 | 457.5 |  | 4.5 (Acid) 11.1 (Base) | 2.2 | |

| 79-57-2 | Oxytetracycline | C22H24N2O9 | 460.4 |  | 4.5 | −1.5 | |

| 60-54-8 | Tetracycline | C22H24N2O8 | 444.4 |  | 4.5 | −1.5 | |

| Glycopeptide | 1404-90-6 | Vancomycin | C66H75Cl2N9O24 | 1449.3 |  | 3.0 | −1.4 |

| Classification | Antimicrobials | Wastewater ID | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commercial Facility | Hospital A | Hospital B | Hospital C | Hospital D | Hospital E | ||

| β-lactams | Ampicillin | 14,175 (N.A.) | 27,584 (60,291) | 24,889 (22,724) | 48,135 (42,096) | 10,083 (10,407) | 40,622 (57,156) |

| Benzylpenicillin | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | 157,797 (220,683) | N.D. | |

| Cefdinir | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | |

| Cefpodoxime | N.D. | 650 (289) | 2406 (2265) | 5039 (3226) | 8623 (16,701) | 824 (372) | |

| Cefpodoxime proxetil | 20 (N.A.) | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | |

| Ceftiofur | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | |

| New quinolones | Ciprofloxacin | 14 (N.A.) | N.D. | 134 (115) | 389 (251) | 184 (142) | 105 (16) |

| Enrofloxacin | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | |

| Levofloxacin | 4815 (7547) | 9632 (22,272) | 5828 (4883) | 8752 (10,153) | 8296 (12,049) | 29,475 (47,798) | |

| Macrolides | Azithromycin | 3531 (N.A.) | 22,722 (42,593) | 1376 (1605) | 436 (60) | 2268 (1923) | 289 (129) |

| Clarithromycin | 4737 (6827) | 3431 (8907) | 2635 (3663) | 2832 (1986) | 1423 (2447) | 1823 (2902) | |

| Tetracyclines | Chlortetracycline | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. |

| Doxycycline | 113 (N.A.) | N.D. | 763 (497) | N.D. | 39 (N.A.) | 723 (N.A.) | |

| Minocycline | 447 (168) | 345 (506) | 272 (5) | 905 (398) | N.D. | N.D. | |

| Oxytetracycline | 38 (N.A.) | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | |

| Tetracycline | 114 (N.A.) | 795 (739) | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | N.D. | |

| Glycopeptide | Vancomycin | 302 (N.A.) | 7257 (5447) | 7933 (4806) | 31,994 (32,731) | 4737 (5129) | 10,990 (9676) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Azuma, T.; Tsukada, A.; Fujii, N.; Katagiri, M.; Nakamura, I.; Shimizu, H.; Tatsuno, K.; Watanabe, M.; Ohmagari, N.; Matsunaga, N. First Multi-Facility Antimicrobial Surveillance in Japanese Hospital Wastewater Reveals Spatiotemporal Trends and Source-Specific Environmental Loads. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010050

Azuma T, Tsukada A, Fujii N, Katagiri M, Nakamura I, Shimizu H, Tatsuno K, Watanabe M, Ohmagari N, Matsunaga N. First Multi-Facility Antimicrobial Surveillance in Japanese Hospital Wastewater Reveals Spatiotemporal Trends and Source-Specific Environmental Loads. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010050

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzuma, Takashi, Ai Tsukada, Naoki Fujii, Miwa Katagiri, Itaru Nakamura, Hidefumi Shimizu, Keita Tatsuno, Manabu Watanabe, Norio Ohmagari, and Nobuaki Matsunaga. 2026. "First Multi-Facility Antimicrobial Surveillance in Japanese Hospital Wastewater Reveals Spatiotemporal Trends and Source-Specific Environmental Loads" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010050

APA StyleAzuma, T., Tsukada, A., Fujii, N., Katagiri, M., Nakamura, I., Shimizu, H., Tatsuno, K., Watanabe, M., Ohmagari, N., & Matsunaga, N. (2026). First Multi-Facility Antimicrobial Surveillance in Japanese Hospital Wastewater Reveals Spatiotemporal Trends and Source-Specific Environmental Loads. Antibiotics, 15(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010050