Clinical and Environmental Plasmids: Antibiotic Resistance, Virulence, Mobility, and ESKAPEE Pathogens

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

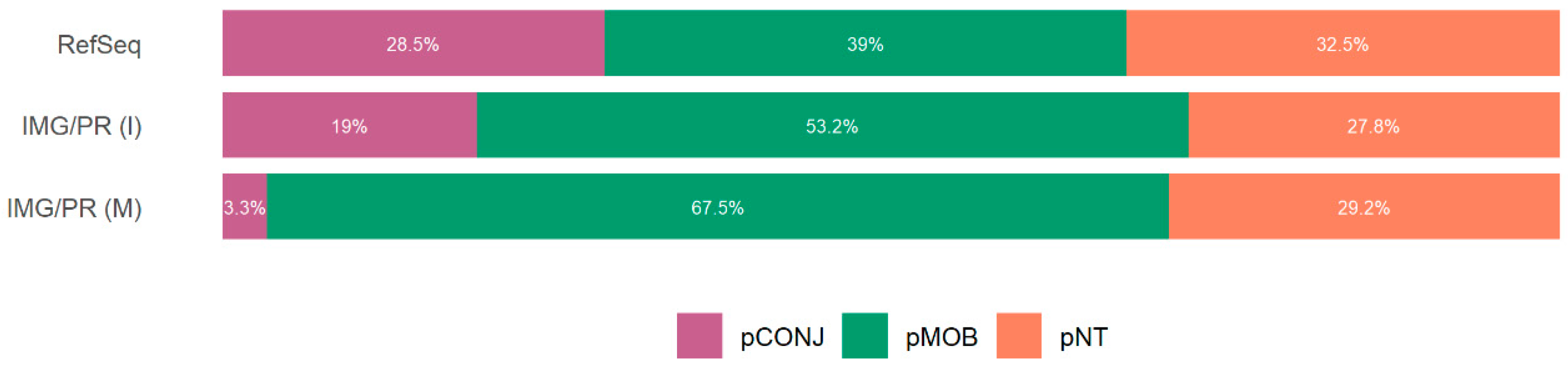

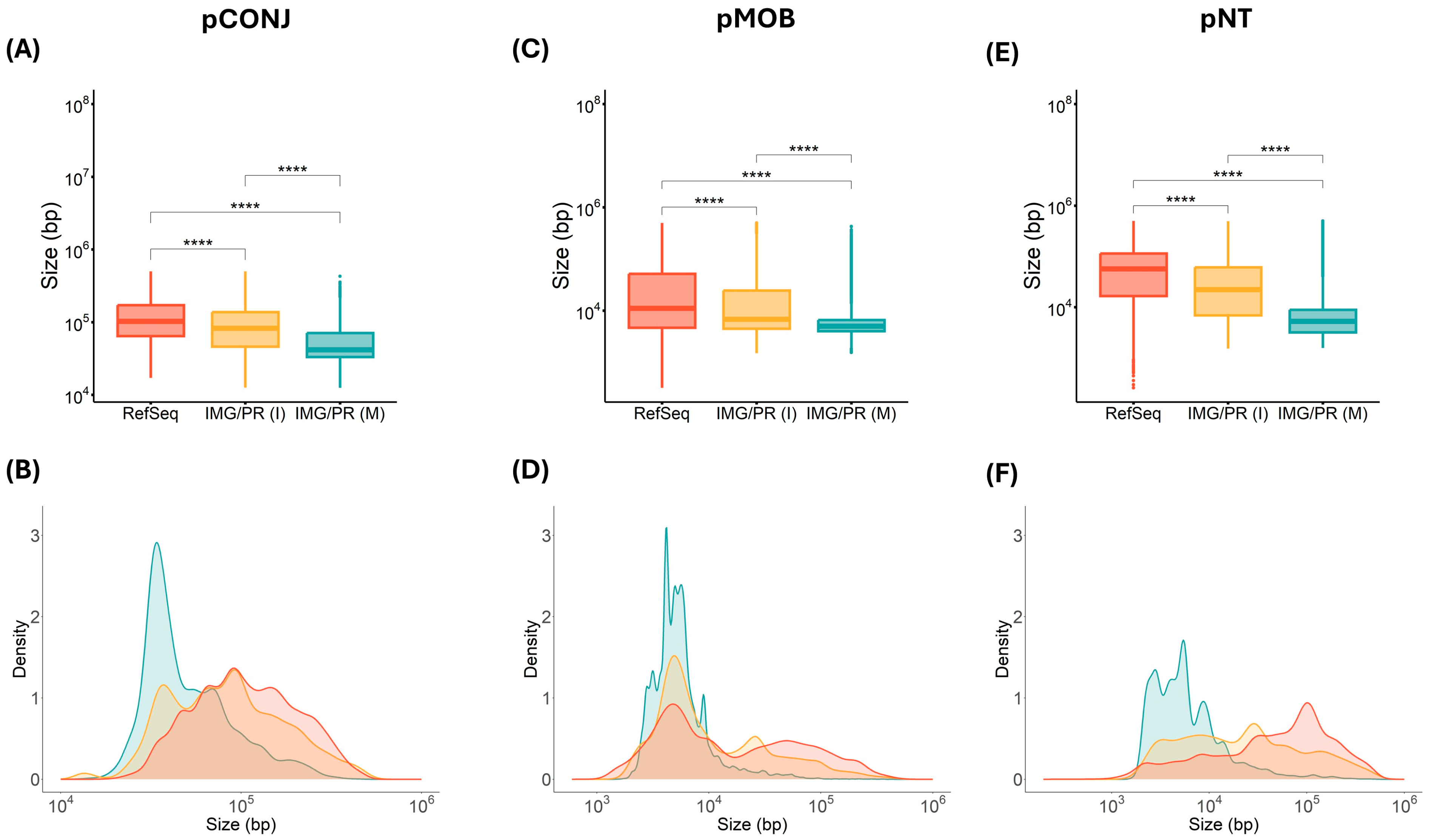

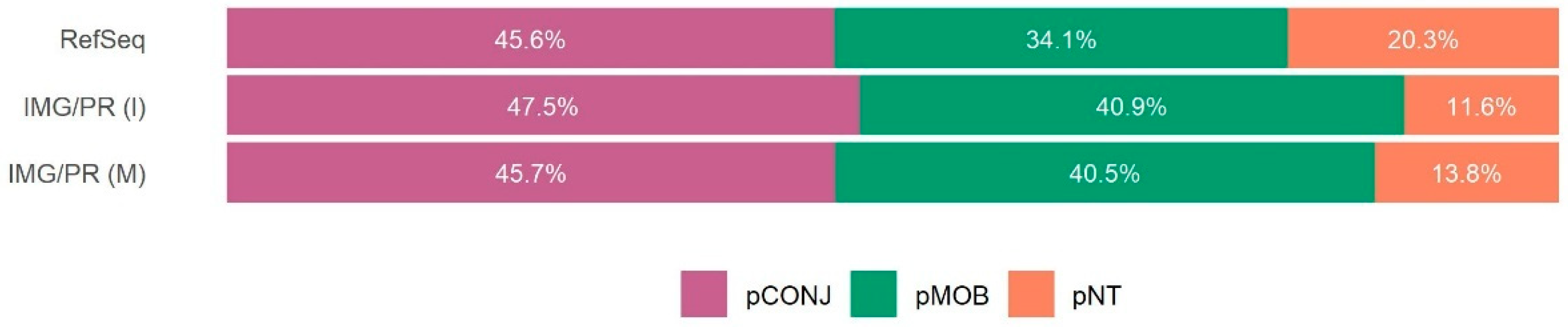

2.1. Mobility and Size of Plasmids

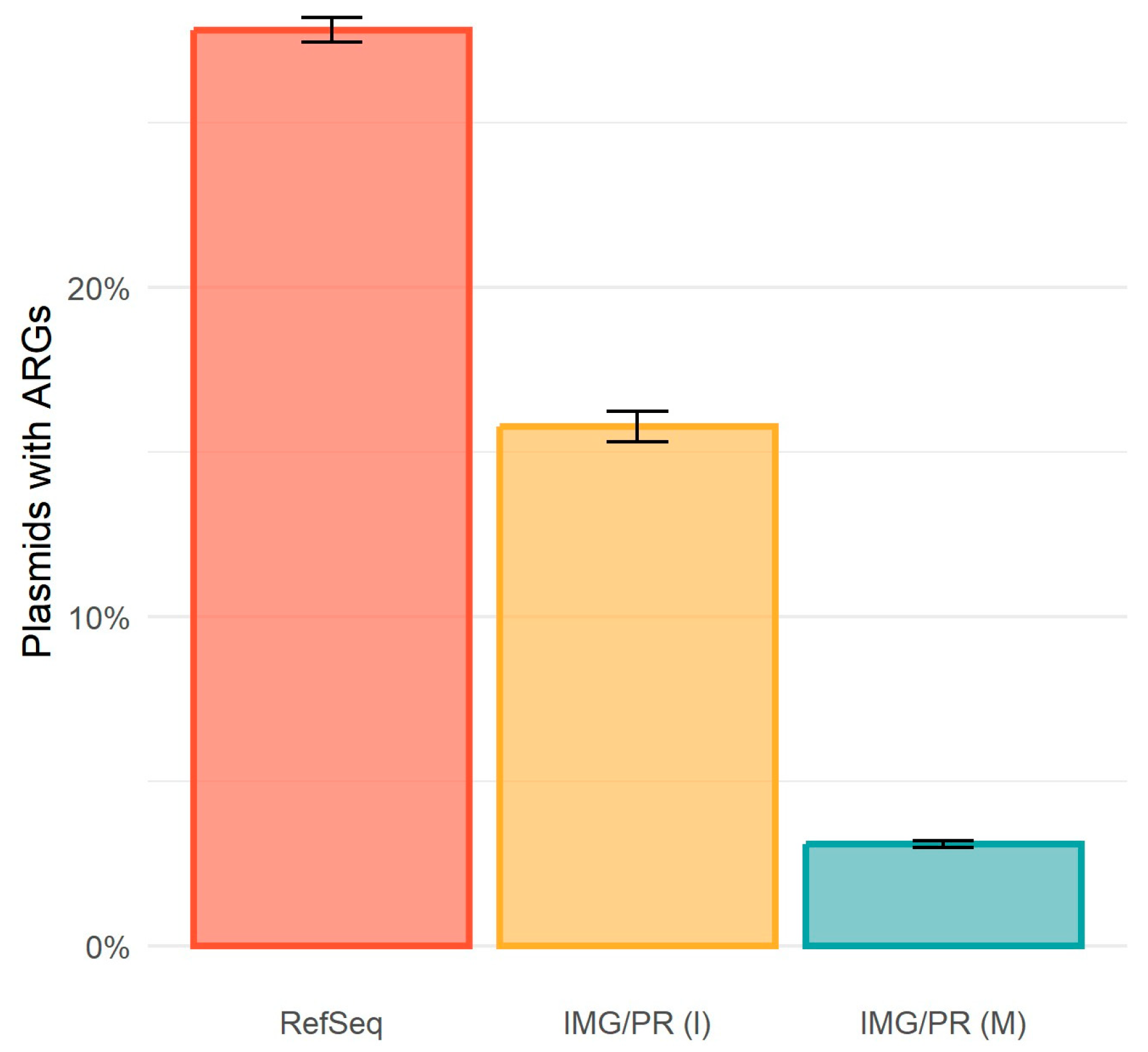

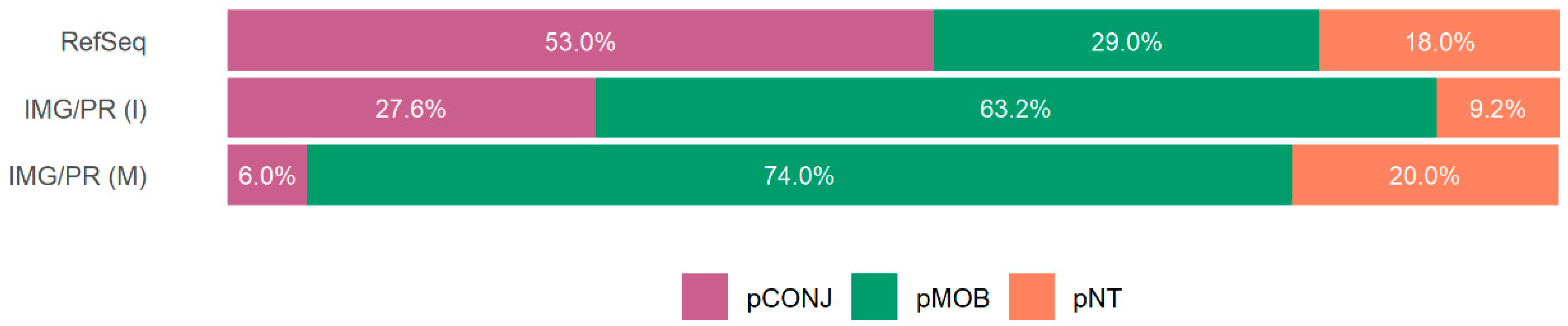

2.2. Antimicrobial Resistance and Plasmid Mobility

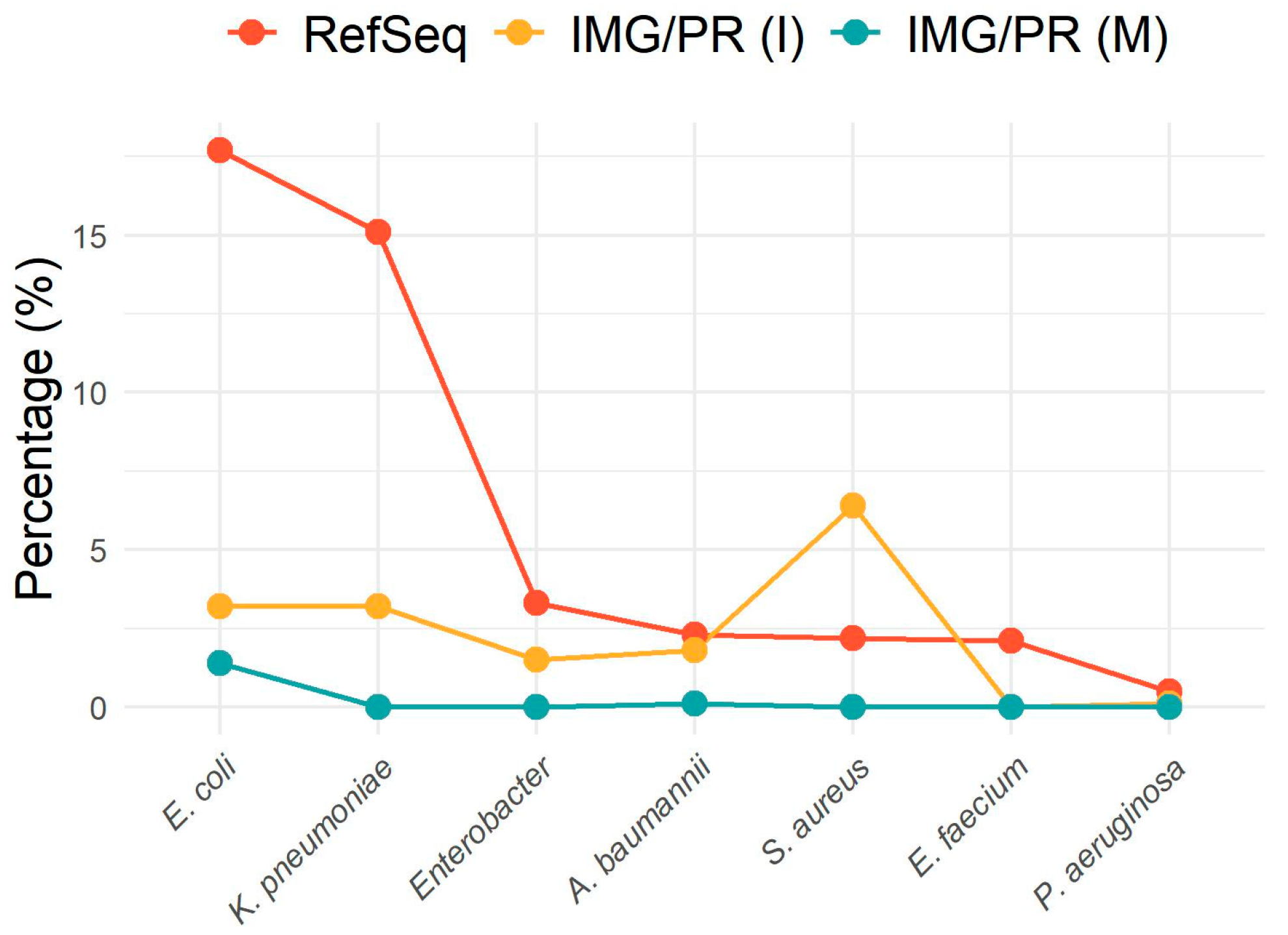

2.3. Antibiotic Resistance in ESKAPEE Pathogens

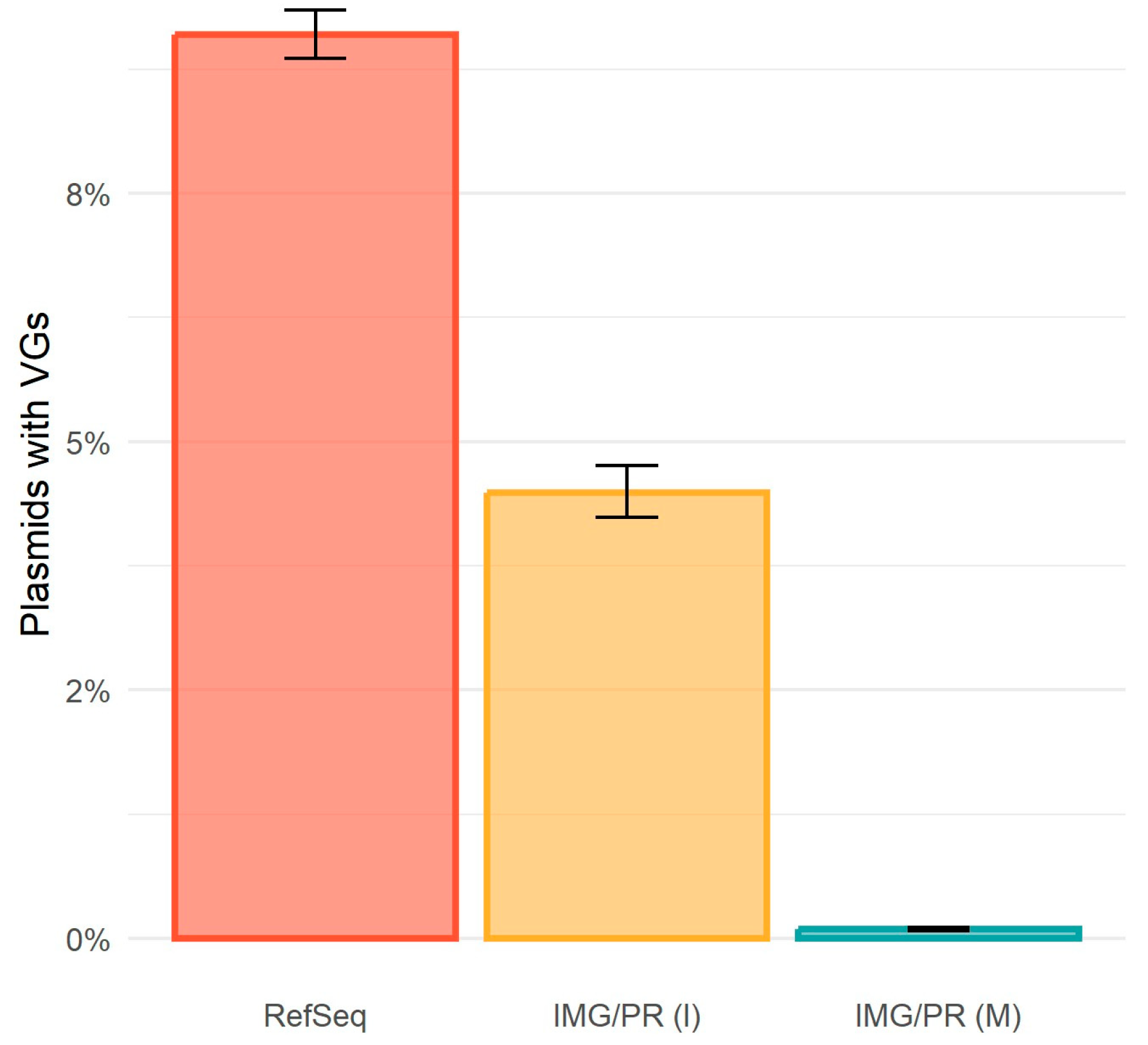

2.4. Virulence and Plasmid Mobility

2.5. Putative Bias in Metagenomic Data

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fogarty, E.C.; Schechter, M.S.; Lolans, K.; Sheahan, M.L.; Veseli, I.; Moore, R.M.; Kiefl, E.; Moody, T.; Rice, P.A.; Yu, M.K.; et al. A Cryptic Plasmid Is among the Most Numerous Genetic Elements in the Human Gut. Cell 2024, 187, 1206–1222.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Dagan, T. The Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance Islands Occurs within the Framework of Plasmid Lineages. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares-Arroyo, M.; Coluzzi, C.; Rocha, E.P.C. Origins of Transfer Establish Networks of Functional Dependencies for Plasmid Transfer by Conjugation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, 3001–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Beltrán, J.; DelaFuente, J.; León-Sampedro, R.; MacLean, R.C.; San Millán, Á. Beyond Horizontal Gene Transfer: The Role of Plasmids in Bacterial Evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 347–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuer, H.; Smalla, K. Plasmids Foster Diversification and Adaptation of Bacterial Populations in Soil. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 1083–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donlan, R.M. Biofilms: Microbial Life on Surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2002, 8, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, T.J.; Nolan, L.K. Pathogenomics of the Virulence Plasmids of Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009, 73, 750–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, S.R.; Kwong, S.M.; Firth, N.; Jensen, S.O. Mobile Genetic Elements Associated with Antimicrobial Resistance. Clin Microbiol. Rev. 2018, 31, e00088-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bottery, M.J. Ecological Dynamics of Plasmid Transfer and Persistence in Microbial Communities. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2022, 68, 102152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Che, Y.; Yang, Y.; Xu, X.; Břinda, K.; Polz, M.F.; Hanage, W.P.; Zhang, T. Conjugative Plasmids Interact with Insertion Sequences to Shape the Horizontal Transfer of Antimicrobial Resistance Genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2008731118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitriu, T. Evolution of Horizontal Transmission in Antimicrobial Resistance Plasmids. Microbiology 2022, 168, 001214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraikin, N.; Couturier, A.; Lesterlin, C. The Winding Journey of Conjugative Plasmids toward a Novel Host Cell. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2024, 78, 102449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Millan, A. Evolution of Plasmid-Mediated Antibiotic Resistance in the Clinical Context. Trends Microbiol. 2018, 26, 978–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schröder, G.; Lanka, E. The Mating Pair Formation System of Conjugative Plasmids—A Versatile Secretion Machinery for Transfer of Proteins and DNA. Plasmid 2005, 54, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smillie, C.; Garcillán-Barcia, M.P.; Francia, M.V.; Rocha, E.P.C.; De La Cruz, F. Mobility of Plasmids. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 434–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares-Arroyo, M.; Nucci, A.; Rocha, E.P.C. Expanding the Diversity of Origin of Transfer-Containing Sequences in Mobilizable Plasmids. Nat. Microbiol. 2024, 9, 3240–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coluzzi, C.; Garcillán-Barcia, M.P.; De La Cruz, F.; Rocha, E.P.C. Evolution of Plasmid Mobility: Origin and Fate of Conjugative and Nonconjugative Plasmids. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022, 39, msac115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, W.R.; Arias, C.A. ESKAPE Pathogens: Antimicrobial Resistance, Epidemiology, Clinical Impact and Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denissen, J.; Reyneke, B.; Waso-Reyneke, M.; Havenga, B.; Barnard, T.; Khan, S.; Khan, W. Prevalence of ESKAPE Pathogens in the Environment: Antibiotic Resistance Status, Community-Acquired Infection and Risk to Human Health. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health 2022, 244, 114006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyenuga, N.; Cobo-Díaz, J.F.; Alvarez-Ordóñez, A.; Alexa, E.-A. Overview of Antimicrobial Resistant ESKAPEE Pathogens in Food Sources and Their Implications from a One Health Perspective. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldfarb, T.; Kodali, V.K.; Pujar, S.; Brover, V.; Robbertse, B.; Farrell, C.M.; Oh, D.-H.; Astashyn, A.; Ermolaeva, O.; Haddad, D.; et al. NCBI RefSeq: Reference Sequence Standards through 25 Years of Curation and Annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2025, 53, D243–D257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, A.P.; Call, L.; Roux, S.; Nayfach, S.; Huntemann, M.; Palaniappan, K.; Ratner, A.; Chu, K.; Mukherjeep, S.; Reddy, T.B.K.; et al. IMG/PR: A Database of Plasmids from Genomes and Metagenomes with Rich Annotations and Metadata. Nucleic Acids Res. 2024, 52, D164–D173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feldgarden, M.; Brover, V.; Gonzalez-Escalona, N.; Frye, J.G.; Haendiges, J.; Haft, D.H.; Hoffmann, M.; Pettengill, J.B.; Prasad, A.B.; Tillman, G.E.; et al. AMRFinderPlus and the Reference Gene Catalog Facilitate Examination of the Genomic Links among Antimicrobial Resistance, Stress Response, and Virulence. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 12728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rice, L.B. Federal Funding for the Study of Antimicrobial Resistance in Nosocomial Pathogens: No ESKAPE. J. Infect. Dis. 2008, 197, 1079–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dib, J.R.; Wagenknecht, M.; Farías, M.E.; Meinhardt, F. Strategies and approaches in plasmidome studies—Uncovering plasmid diversity disregarding of linear elements? Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirstahler, P.; Teudt, F.; Otani, S.; Aarestrup, F.M.; Pamp, S.J. A Peek into the Plasmidome of Global Sewage. mSystems 2021, 6, e00283-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Néron, B.; Denise, R.; Coluzzi, C.; Touchon, M.; Rocha, E.P.C.; Abby, S.S. MacSyFinder v2: Improved Modelling and Search Engine to Identify Molecular Systems in Genomes. Peer Community J. 2023, 3, e28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.D.; Khanal, S.; Bäcker, L.E.; Lood, C.; Kerremans, A.; Gorivale, S.; Begyn, K.; Cambré, A.; Rajkovic, A.; Devlieghere, F.; et al. Rapid Evolutionary Tuning of Endospore Quantity versus Quality Trade-off via a Phase-Variable Contingency Locus. Curr. Biol. 2024, 34, 3077–3085.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zheng, D.; Zhou, S.; Chen, L.; Yang, J. VFDB 2022: A General Classification Scheme for Bacterial Virulence Factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D912–D917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and Applications. BMC Bioinform. 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cury, J.; Abby, S.S.; Doppelt-Azeroual, O.; Néron, B.; Rocha, E.P.C. Identifying Conjugative Plasmids and Integrative Conjugative Elements with CONJscan. In Horizontal Gene Transfer; Methods in Molecular Biology; De La Cruz, F., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2075, pp. 265–283. ISBN 978-1-4939-9876-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sayers, E.W.; Bolton, E.E.; Brister, J.R.; Canese, K.; Chan, J.; Comeau, D.C.; Connor, R.; Funk, K.; Kelly, C.; Kim, S.; et al. Database Resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, D20–D26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Antipov, D.; Hartwick, N.; Shen, M.; Raiko, M.; Lapidus, A.; Pevzner, P.A. plasmidSPAdes: Assembling Plasmids from Whole Genome Sequencing Data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 3380–3387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Identity (%) | Total (%) | pCONJ (%) | pMOB (%) | pNT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 3.09 | 5.60 | 3.39 | 2.12 |

| 80 | 3.45 | 6.00 | 3.89 | 2.16 |

| 70 | 3.52 | 6.14 | 3.98 | 2.20 |

| Dataset | ESKAPEE Pathogens | Number of Plasmids | Number of Plasmids with ARGs | Percentage of Plasmids with ARGs | Adjusted Residuals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RefSeq | A. baumannii | 1204 | 372 | 30.9 | 1.4 |

| IMG/PR (I) | 456 | 161 | 35.3 | 3.0 | |

| IMG/PR (M) | 127 | 0 | 0 | −7.6 | |

| RefSeq | Enterobacter sp. | 1744 | 764 | 43.8 | 5.0 |

| IMG/PR (I) | 358 | 106 | 29.6 | −5.0 | |

| IMG/PR (M) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | |

| RefSeq | E. faecium | 1116 | 429 | 38.4 | NA |

| IMG/PR (I) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | |

| IMG/PR (M) | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA | |

| RefSeq | E. coli | 9343 | 3746 | 40.1 | 33.7 |

| IMG/PR (I) | 777 | 117 | 15.1 | −10.7 | |

| IMG/PR (M) | 1773 | 5 | 0.3 | −31.4 | |

| RefSeq | K. pneumoniae | 7977 | 4223 | 52.9 | 0.2 |

| IMG/PR (I) | 790 | 427 | 54.1 | 0.7 | |

| IMG/PR (M) | 28 | 3 | 10.7 | −4.5 | |

| RefSeq | P. aeruginosa | 285 | 128 | 44.9 | 2.4 |

| IMG/PR (I) | 36 | 17 | 47.2 | 0.7 | |

| IMG/PR (M) | 25 | 0 | 0 | −4.4 | |

| RefSeq | S. aureus | 1157 | 719 | 62.1 | −5.0 |

| IMG/PR (I) | 1590 | 1132 | 71.2 | 5.0 | |

| IMG/PR (M) | 1 | 1 | 100 | 0.7 |

| Plasmids Remaining (%) | Number of Plasmids | Mean Length | Minimum Length | pCONJ (%) | pMOB (%) | pNT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 129,320 | 9996.8 | 1546 | 3.30 | 67.45 | 29.25 |

| 90 | 116,388 | 10,831.1 | 2834 | 3.67 | 69.63 | 26.70 |

| 80 | 103,456 | 11,795.0 | 3463 | 4.13 | 69.67 | 26.20 |

| 70 | 90,524 | 12,933.2 | 4138 | 4.72 | 69.11 | 26.17 |

| 60 | 77,592 | 14,375.3 | 4551 | 5.50 | 66.59 | 27.91 |

| 50 | 64,660 | 16,275.3 | 5165 | 6.60 | 63.63 | 29.77 |

| 40 | 51,728 | 18,979.9 | 5697 | 8.25 | 62.67 | 29.07 |

| 30 | 38,796 | 23,270.7 | 6693 | 11.01 | 55.21 | 33.78 |

| Plasmids Remaining (%) | Number of Plasmids | Mean Length | Minimum Length | Plasmids with ARGs (%) | pCONJ (%) | pMOB (%) | pNT (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 129,320 | 9996.8 | 1546 | 3.09 | 5.60 | 3.39 | 2.12 |

| 90 | 116,388 | 10,831.1 | 2834 | 3.27 | 5.60 | 3.56 | 2.22 |

| 80 | 103,456 | 11,795.0 | 3463 | 3.61 | 5.60 | 3.98 | 2.30 |

| 70 | 90,524 | 12,933.2 | 4138 | 4.04 | 5.60 | 4.49 | 2.56 |

| 60 | 77,592 | 14,375.3 | 4551 | 4.48 | 5.60 | 5.11 | 2.77 |

| 50 | 64,660 | 16,275.3 | 5165 | 5.09 | 5.60 | 6.00 | 3.02 |

| 40 | 51,728 | 18,979.9 | 5697 | 4.62 | 5.60 | 4.86 | 3.85 |

| 30 | 38,796 | 23,270.7 | 6693 | 5.53 | 5.60 | 6.21 | 4.38 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Domingues, C.P.F.; Rebelo, J.S.; Dionisio, F.; Nogueira, T. Clinical and Environmental Plasmids: Antibiotic Resistance, Virulence, Mobility, and ESKAPEE Pathogens. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010029

Domingues CPF, Rebelo JS, Dionisio F, Nogueira T. Clinical and Environmental Plasmids: Antibiotic Resistance, Virulence, Mobility, and ESKAPEE Pathogens. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):29. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010029

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomingues, Célia P. F., João S. Rebelo, Francisco Dionisio, and Teresa Nogueira. 2026. "Clinical and Environmental Plasmids: Antibiotic Resistance, Virulence, Mobility, and ESKAPEE Pathogens" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010029

APA StyleDomingues, C. P. F., Rebelo, J. S., Dionisio, F., & Nogueira, T. (2026). Clinical and Environmental Plasmids: Antibiotic Resistance, Virulence, Mobility, and ESKAPEE Pathogens. Antibiotics, 15(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010029