Occurrence of Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from the Environmental Water from Tamaulipas, Mexico

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

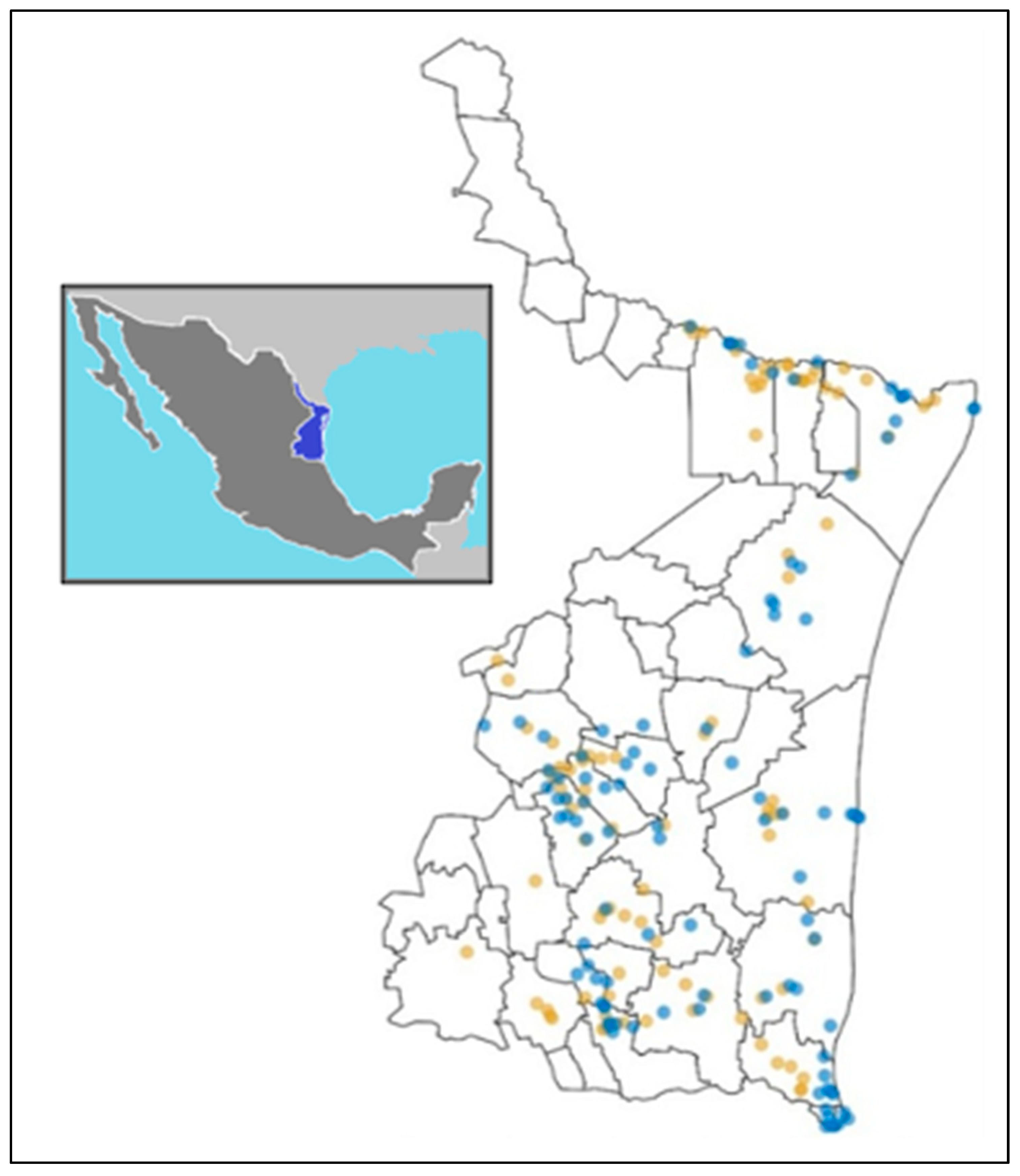

2.1. Sampling

2.2. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolation

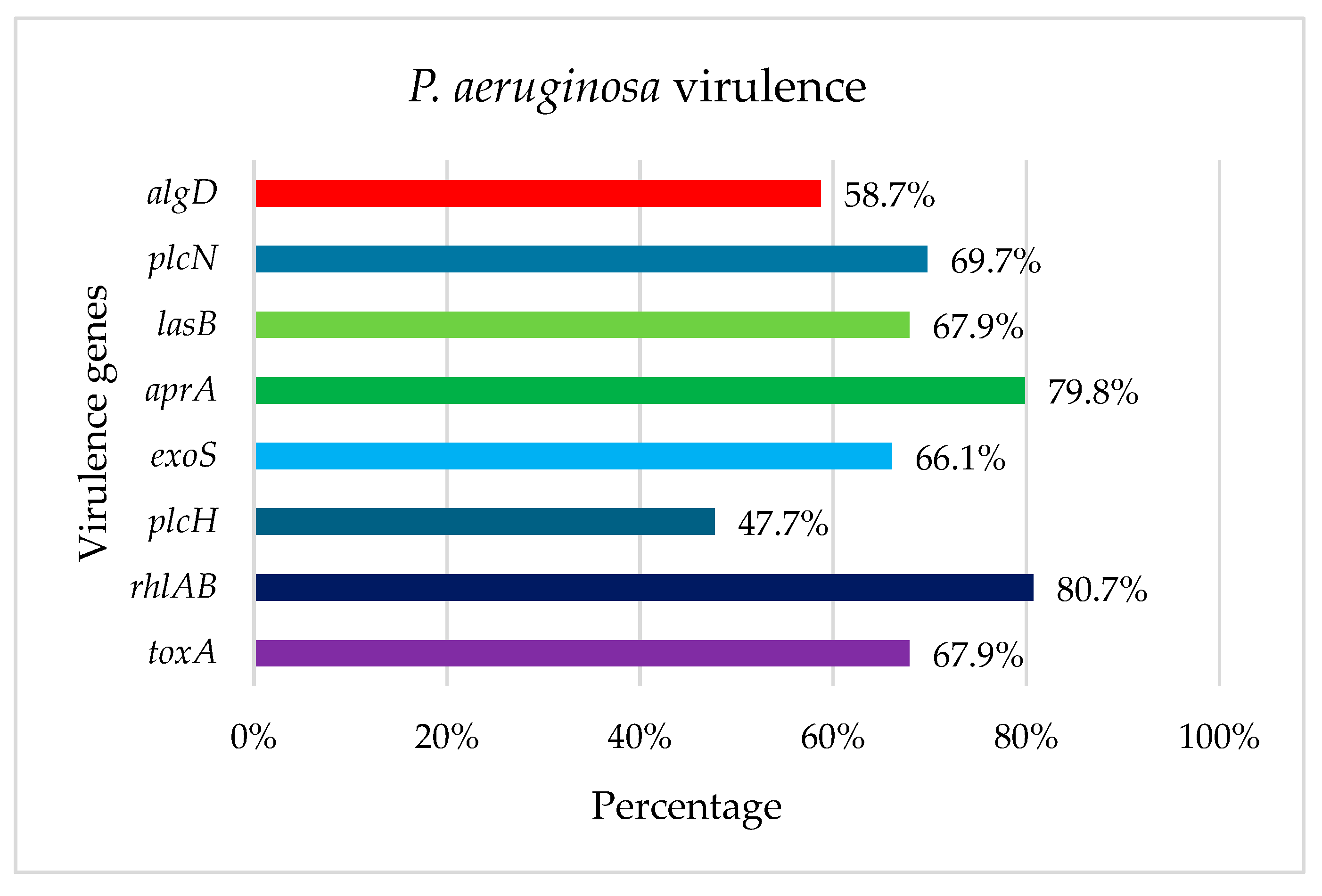

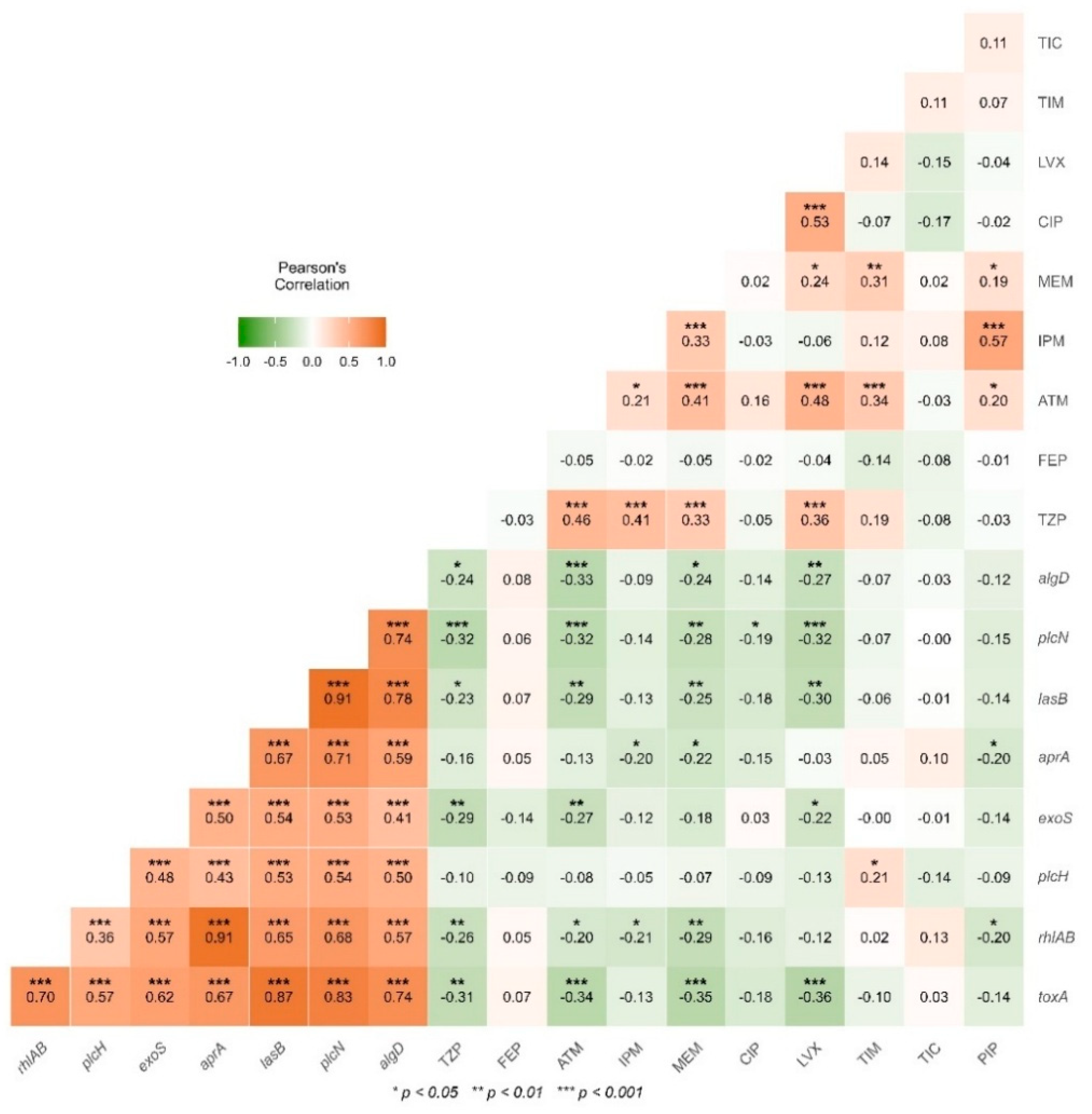

2.3. Detection of Virulence Genes

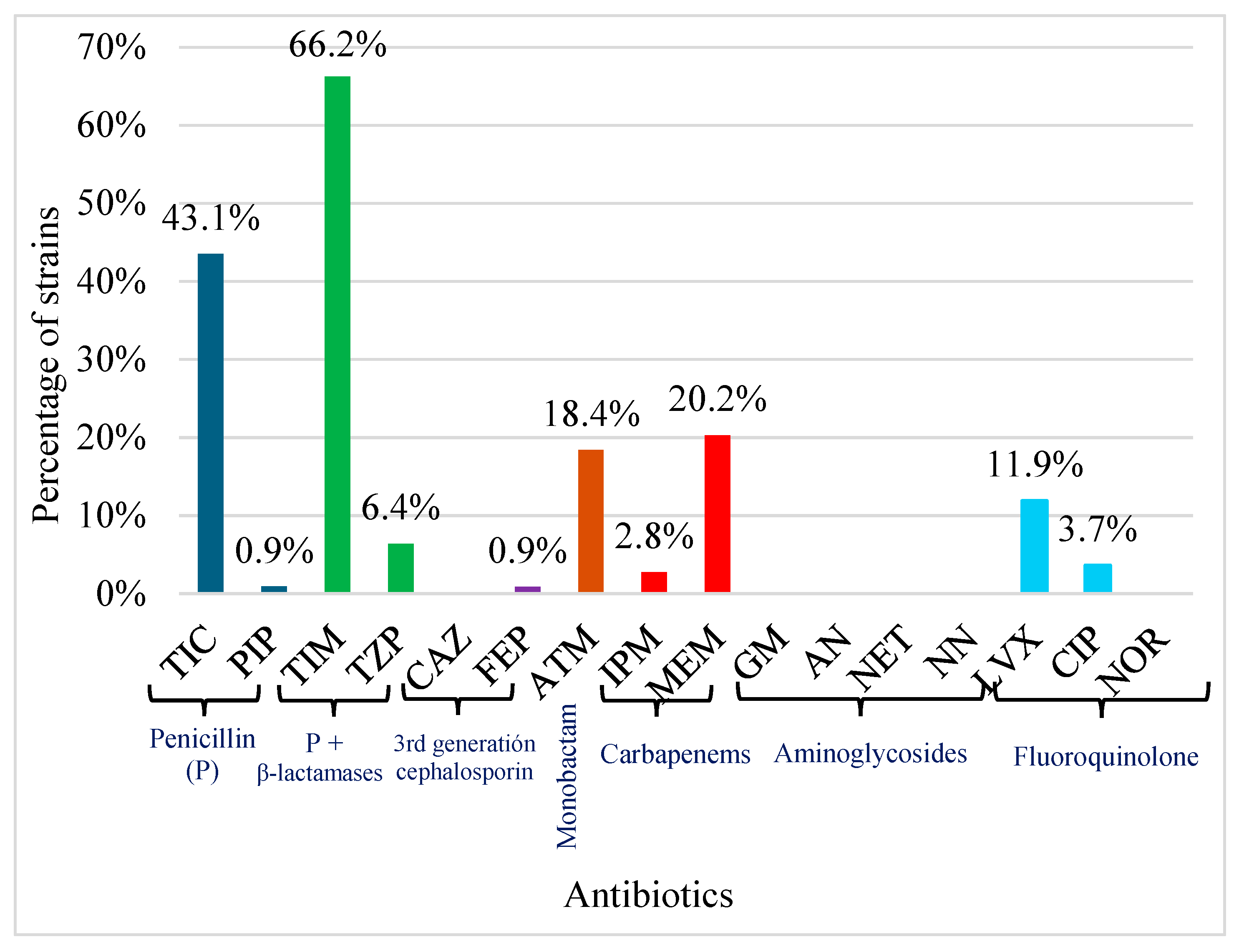

2.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.5. Detection Class 1 Integrons

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Sampling

4.2. Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolation

4.3. Detection of Virulence Genes

4.4. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

4.5. Detection of Class 1 Integrons

4.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amato, M.; Dasí, D.; González, A.; Ferrús, M.A.; Castillo, M.Á. Occurrence of Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria and Resistance Genes in Agricultural Irrigation Waters from Valencia City (Spain). Agric. Water Manag. 2021, 256, 107097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Muñoz, J.; Aznar-Sánchez, J.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.; Román-Sánchez, I. Sustainable Water Use in Agriculture: A Review of Worldwide Research. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhou, S.; Shi, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Wu, S. Heavy Metals in Food Crops, Soil, and Water in the Lihe River Watershed of the Taihu Region and Their Potential Health Risks When Ingested. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 615, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, S.; Usman, Q.A. Heavy Metal Contamination in Water of Indus River and Its Tributaries, Northern Pakistan: Evaluation for Potential Risk and Source Apportionment. Toxin Rev. 2022, 41, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z. Distribution and Ecological Risk Assessment of Typical Antibiotics in the Surface Waters of Seven Major Rivers, China. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2021, 23, 1088–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehalt Macedo, H.; Lehner, B.; Nicell, J.A.; Khan, U.; Klein, E.Y. Antibiotics in the Global River System Arising from Human Consumption. PNAS Nexus 2025, 4, pgaf096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivanova, A.; Wiberg, K.; Ahrens, L.; Zubcov, E.; Dahlberg, A.-K. Spatial Distribution of Legacy Pesticides in River Sediment from the Republic of Moldova. Chemosphere 2021, 279, 130923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhao, W.; Yang, C.; Li, Y.; Liu, M.; Meng, X.; Cai, M. Assessment of Currently Used Organochlorine Pesticides in Surface Water and Sediments in Xiangjiang River, a Drinking Water Source in China: Occurrence and Distribution Characteristics under Flood Events. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 304, 119133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Guo, X.; Hua, G.; Li, G.; Feng, R.; Liu, X. Migration and Degradation of Swine Farm Tetracyclines at the River Catchment Scale: Can the Multi-Pond System Mitigate Pollution Risk to Receiving Rivers? Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, M.J.T.L.; Pontes, G.; Serra, P.T.; Balieiro, A.; Castro, D.; Pieri, F.A.; Crainey, J.L.; Nogueira, P.A.; Orlandi, P.P. Multidrug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Survey in a Stream Receiving Effluents from Ineffective Wastewater Hospital Plants. BMC Microbiol. 2016, 16, 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Roberts, D.J.; Du, H.-N.; Yu, X.-F.; Zhu, N.-Z.; Meng, X.-Z. Persistence of Antibiotic Resistance Genes from River Water to Tap Water in the Yangtze River Delta. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Ngo, H.H.; Guo, W.; Chang, S.W.; Nguyen, D.D.; Liu, Y.; Wei, Q.; Wei, D. A Critical Review on Antibiotics and Hormones in Swine Wastewater: Water Pollution Problems and Control Approaches. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 387, 121682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Mehmood, S.; Rasheed, T.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Antibiotics Traces in the Aquatic Environment: Persistence and Adverse Environmental Impact. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2020, 13, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias-Andres, M.; Klümper, U.; Rojas-Jimenez, K.; Grossart, H.-P. Microplastic Pollution Increases Gene Exchange in Aquatic Ecosystems. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sta Ana, K.M.; Madriaga, J.; Espino, M.P. β-Lactam Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance in Asian Lakes and Rivers: An Overview of Contamination, Sources and Detection Methods. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 275, 116624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Fu, Y.-H.; Sheng, H.-J.; Topp, E.; Jiang, X.; Zhu, Y.-G.; Tiedje, J.M. Antibiotic Resistance in the Soil Ecosystem: A One Health Perspective. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2021, 20, 100230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, J.; Li, Z.; Guo, S.; Li, K.; Xu, P.; Ok, Y.S.; Jones, D.L.; Zou, J. Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Agricultural Soils: A Systematic Analysis. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 53, 847–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ondon, B.S.; Ho, S.-H.; Li, F. Emerging Soil Contamination of Antibiotics Resistance Bacteria (ARB) Carrying Genes (ARGs): New Challenges for Soil Remediation and Conservation. Environ. Res. 2023, 219, 115132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licea-Herrera, J.I.; Guerrero, A.; Mireles-Martínez, M.; Rodríguez-González, Y.; Aguilera-Arreola, G.; Contreras-Rodríguez, A.; Fernandez-Davila, S.; Requena-Castro, R.; Rivera, G.; Bocanegra-García, V.; et al. Agricultural Soil as a Reservoir of Pseudomonas aeruginosa with Potential Risk to Public Health. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 2181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, J.; Guan, Y.; Cheng, M.; Chen, H.; He, J.; Wang, S.; Wang, Z. Occurrence and Distribution of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Ba River, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Qin, S.; Guan, X.; Jiang, K.; Jiang, M.; Liu, F. Distribution of Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Karst River and Its Ecological Risk. Water Res. 2021, 203, 117507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Zhao, F.; Li, R.; Jin, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; Li, S.; Shu, Q.; Na, G. Occurrence and Distribution of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Water of Liaohe River Basin, China. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solís-Soto, L.; Castro-Delgado, Z.L.; García, S.; Heredia, N.; Avila-Sosa, R.; Dávila-Aviña, J.E. Pathogenic Bacteria and Their Antibiotic Resistance Profile in Irrigation Water in Farms from Mexico. J. Water Sanit. Hyg. Dev. 2024, 14, 565–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Zaragoza, M.; Rodriguez-Preciado, S.Y.; Hernández-Ventura, L.; Ortiz-Covarrubias, A.; Castellanos-García, G.; Sifuentes-Franco, S.; Pereira-Suárez, A.L.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F.; Montoya-Buelna, M.; Macias-Barragan, J. Evaluation of Antibiotic Resistance in Escherichia coli Isolated from a Watershed Section of Ameca River in Mexico. Microbiol. Res. 2025, 16, 186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena-Castro, R.; Aguilera-Arreola, M.G.; Martínez-Vázquez, A.V.; Cruz-Pulido, W.L.; Rivera, G.; Fernández-Dávila, S.; Flores-Magallón, R.; Acosta-Cruz, E.; Bocanegra-García, V. Identification of Bacterial Communities in Surface Waters of Rio Bravo/Rio Grande Through 16S rRNA Gene Metabarcoding. Water 2025, 17, 1575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, M.; Chu, L.M. Occurrence of Antibiotics and Antibiotic Resistance Genes in Soils from Wastewater Irrigation Areas in the Pearl River Delta Region, Southern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 624, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Requena-Castro, R.; Aguilera-Arreola, M.G.; Martínez-Vázquez, A.V.; Cruz-Pulido, W.L.; Rivera, G.; Bocanegra-García, V. Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence Genes, and ESBL (Extended Spectrum Beta-Lactamase) Production Analysis in E. coli Strains from the Rio Grande/Rio Bravo River in Tamaulipas, Mexico. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 2401–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elahi, G.; Goli, H.R.; Shafiei, M.; Nikbin, V.S.; Gholami, M. Antimicrobial Resistance, Virulence Gene Profiling, and Genetic Diversity of Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates in Mazandaran, Iran. BMC Microbiol. 2024, 24, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edward, E.A.; El Shehawy, M.R.; Abouelfetouh, A.; Aboulmagd, E. Prevalence of Different Virulence Factors and Their Association with Antimicrobial Resistance among Pseudomonas aeruginosa Clinical Isolates from Egypt. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M.S.; Furlan, J.P.R.; Dos Santos, L.D.R.; Rosa, R.D.S.; Savazzi, E.A.; Stehling, E.G. Patterns of Antimicrobial Resistance and Metal Tolerance in Environmental Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates and the Genomic Characterization of the Rare O6/ST900 Clone. Env. Monit. Assess. 2023, 195, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhimi, R.; Tayh, G.; Ghariani, S.; Chairat, S.; Chaouachi, A.; Boudabous, A.; Slama, K.B. Distribution, Diversity and Antibiotic Resistance of Pseudomonas Spp. Isolated from the Water Dams in the North of Tunisia. Curr. Microbiol. 2022, 79, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantino-Teles, P.; Jouault, A.; Touqui, L.; Saliba, A.M. Role of Host and Bacterial Lipids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Respiratory Infections. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 931027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado-Martín, I.; Sainz-Mejías, M.; McClean, S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An Audacious Pathogen with an Adaptable Arsenal of Virulence Factors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgado, S.M.; Bighi, N.M.S.; Freitas, F.S.; Rodrigues, C.; Fonseca, É.L.; Vicente, A.C. Carbapenem-Resistant Hypervirulent P. Aeruginosa Coexpressing exoS/exoU in Brazil. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 43, 233–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, R.; Amir, M.; Anjum, S.; Ur Rehman, M.; Noorul Hasan, T.; Sajjad Naqvi, S.; Faryal, R.; Ali Khan, H.; Khadija, B.; Arshad, N.; et al. Presence of T3SS (exoS, exoT, exoU and exoY), Susceptibility Pattern and MIC of MDR-Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Burn Wounds. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2023, 17, 1130–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, T.; Stapleton, F.; Willcox, M. Differences in Antimicrobial Resistance between exoU and exoS Isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2025, 44, 1629–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Raudonis, R.; Glick, B.R.; Lin, T.-J.; Cheng, Z. Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Mechanisms and Alternative Therapeutic Strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aldred, K.J.; Kerns, R.J.; Osheroff, N. Mechanism of Quinolone Action and Resistance. Biochemistry 2014, 53, 1565–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M.S.; Furlan, J.P.R.; Gallo, I.F.L.; Dos Santos, L.D.R.; De Campos, T.A.; Savazzi, E.A.; Stehling, E.G. High Level of Resistance to Antimicrobials and Heavy Metals in Multidrug-Resistant Pseudomonas Sp. Isolated from Water Sources. Curr. Microbiol. 2020, 77, 2694–2701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassuna, N.A.; Darwish, M.K.; Sayed, M.; Ibrahem, R.A. Molecular Epidemiology and Mechanisms of High-Level Resistance to Meropenem and Imipenem in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Individ. Differ. Res. 2020, 13, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobezie, M.Y.; Hassen, M.; Tesfaye, N.A.; Solomon, T.; Demessie, M.B.; Kassa, T.D.; Wendie, T.F.; Andualem, A.; Alemayehu, E.; Belayneh, Y.M. Prevalence of Meropenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Ethiopia: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2024, 13, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, Research, and Development of New Antibiotics: The WHO Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvà-Serra, F.; Jaén-Luchoro, D.; Marathe, N.P.; Adlerberth, I.; Moore, E.R.B.; Karlsson, R. Responses of Carbapenemase-Producing and Non-Producing Carbapenem-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Strains to Meropenem Revealed by Quantitative Tandem Mass Spectrometry Proteomics. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1089140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farhan, S.M.; Raafat, M.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Abd El-Baky, R.M.; Abdalla, S.; EL-Gendy, A.O.; Azmy, A.F. Effect of Imipenem and Amikacin Combination against Multi-Drug Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güssow, D.; Clackson, T. Direct Clone Characterization from Plaques and Colonies by the Polymerase Chain Reaction. Nucl. Acids Res. 1989, 17, 4000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talukder, A.; Rahman, M.M.; Chowdhury, M.M.H.; Mobashshera, T.A.; Islam, N.N. Plasmid Profiling of Multiple Antibiotic-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from Soil of the Industrial Area in Chittagong, Bangladesh. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 2021, 10, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanotte, P.; Watt, S.; Mereghetti, L.; Dartiguelongue, N.; Rastegar-Lari, A.; Goudeau, A.; Quentin, R. Genetic Features of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolates from Cystic Fibrosis Patients Compared with Those of Isolates from Other Origins. J. Med. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Bandara, R.; Conibear, T.C.R.; Thuruthyil, S.J.; Rice, S.A.; Kjelleberg, S.; Givskov, M.; Willcox, M.D.P. Pseudomonas aeruginosa with LasI Quorum-Sensing Deficiency during Corneal Infection. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2004, 45, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinstein, M.P. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Supplement M100, 33rd ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kargar, M.; Mohammadalipour, Z.; Doosti, A.; Lorzadeh, S.; Japoni-Nejad, A. High Prevalence of Class 1 to 3 Integrons Among Multidrug-Resistant Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Southwest of Iran. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2014, 5, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Patterns Number | Resistance Pattern | Number of Strains |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | CIP + LVX | 2 |

| 2 | TIC | 12 |

| 3 | TIC + ATM | 3 |

| 4 | TIC + MEM | 8 |

| 5 | TIC + MEM + ATM | 4 |

| 6 | TIM | 14 |

| 7 | TIM + MEM + ATM + CIP + LVX | 1 |

| 8 | TIM + MEM + ATM + LVX | 5 |

| 9 | TIM + MEM + FEP | 1 |

| 10 | TIM + MEM + IPM + TZP | 1 |

| 11 | TIM + TIC | 22 |

| 12 | TIM + TIC + LVX | 1 |

| 13 | TIM + TIC + MEM | 3 |

| 14 | TIM + TIC + MEM + ATM | 5 |

| 15 | TIM + TIC + PIP + ATM + MEM + IPM | 1 |

| 16 | TZP + ATM + IPM +MEM +TIM +TIC | 1 |

| Target Genes | Size (bp) | Primer Sequence 5′→3′ | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| algD | 1310 | ATGCGAATCAGCATCTTTGGT CTACCAGCAGATGCCCTCGGG | [47] |

| exoS | 504 | CTTGAAGGGACTCGACAAGG TTCAGGTCCGCGTAGTGAAT | [47] |

| plcH | 307 | GAAGCCATGGGCTACTTCAA AGAGTGACGAGGAGCGGTAG | [47] |

| toxA | 352 | GGTAACCAGCTCAGCCACAT TGATGTCCAGGTCATGCTTC | [47] |

| aprA | 140 | ACCCTGTCCTATTCGTTCC GATTGCAGCGACAACTTGG | [48] |

| lasB | 300 | GGAATGAACGAAGCGTTCTC GGTCCAGTAGTAGCGGTTGG | [47] |

| rhlAB | 151 | TCATGGAATTGTCACAACCGC ATACGGCAAAATCATGGCAAC | [48] |

| plcN | 466 | GTTATCGCAACCAGCCCTAC AGGTCGAACACCTGGAACAC | [47] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Licea-Herrera, J.I.; Guerrero, A.; Guel, P.; Bocanegra-García, V.; Rivera, G.; Martínez-Vázquez, A.V. Occurrence of Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from the Environmental Water from Tamaulipas, Mexico. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1278. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121278

Licea-Herrera JI, Guerrero A, Guel P, Bocanegra-García V, Rivera G, Martínez-Vázquez AV. Occurrence of Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from the Environmental Water from Tamaulipas, Mexico. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1278. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121278

Chicago/Turabian StyleLicea-Herrera, Jessica I., Abraham Guerrero, Paulina Guel, Virgilio Bocanegra-García, Gildardo Rivera, and Ana Verónica Martínez-Vázquez. 2025. "Occurrence of Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from the Environmental Water from Tamaulipas, Mexico" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1278. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121278

APA StyleLicea-Herrera, J. I., Guerrero, A., Guel, P., Bocanegra-García, V., Rivera, G., & Martínez-Vázquez, A. V. (2025). Occurrence of Virulence and Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa Isolated from the Environmental Water from Tamaulipas, Mexico. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1278. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121278