Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Resistance Mechanisms, Emerging Therapies, and Prevention—A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

- Non-peer-reviewed sources (e.g., editorials, narrative reviews without original data, opinion papers)

- Conference abstracts lacking full data or without an associated full-text article

- Non-English articles (unless a verified translation was available)

- Studies conducted exclusively in vitro that did not provide clinically relevant information on resistance mechanisms or drug properties

- Articles not specifically addressing MDR/XDR/CRAB A. baumannii or unrelated to antimicrobial resistance and ICU/healthcare-associated infections

2.3. Data Extraction and Synthesis

3. Epidemiology and Clinical Significance

3.1. Community-Acquired Infections Versus Healthcare-Associated Infections

3.2. Global Resistance Trends

3.3. Regional Data from Romania

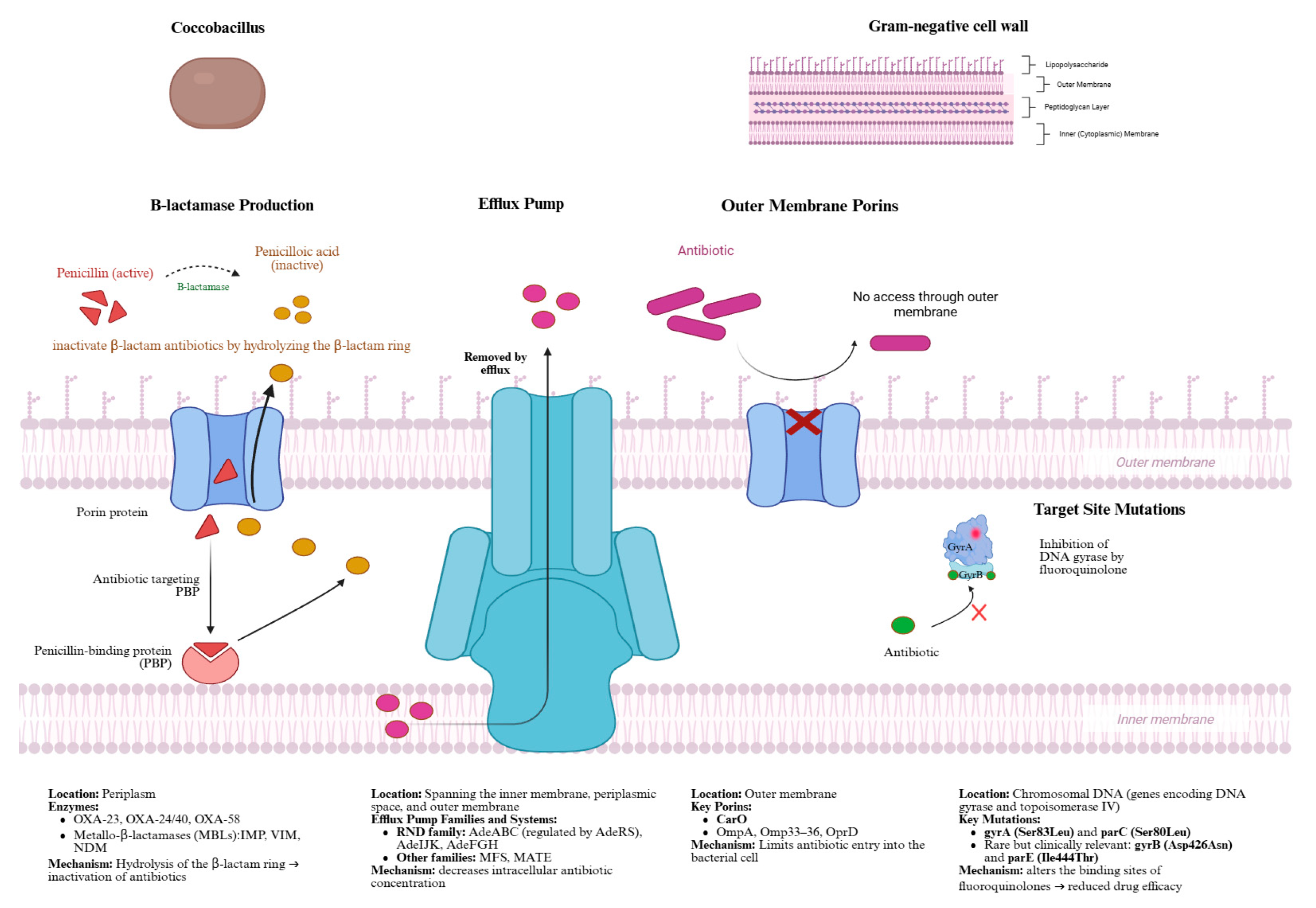

4. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii

4.1. β-Lactamase Production and Carbapenem Resistance

4.2. Efflux Pumps

4.3. Outer Membrane Porins

4.4. Fluoroquinolone Resistance via Target Site Mutations

4.5. Clinical Implications

5. Current Treatment Options and Emerging Therapies

5.1. Colistin

5.2. Cefiderocol

5.3. Tigecycline

5.4. Combination Therapies

5.4.1. Comparative Efficacy: Colistin Plus Tigecycline vs. Colistin Plus Carbapenem

5.4.2. Ceftazidime/Avibactam

5.4.3. Sulbactam–Durlobactam

6. Prevention

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AB | Acinetobacter baumannii |

| AbeM | Acinetobacter efflux pump type MATE |

| ACB | Acinetobacter calcoaceticus–baumannii |

| ADC | Acinetobacter-Derived Cephalosporinase |

| AdeABC | Multidrug efflux pump system |

| AmpC | Class C cephalosporinase |

| AMR | Antimicrobial Resistance |

| AmvA | Acinetobacter multiple valence efflux type A |

| APEKS-NP | Acinetobacter-Pseudomonas Evaluation for Carbapenem Susceptibility—Non-fermenter Panel |

| ArmA | Aminoglycoside resistance methyltransferase |

| APC | Article Processing Charge |

| AST | Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| ATTACK | Acinetobacter Treatment Trial Against Colistin-Resistant A. baumannii |

| blaSHV | Beta-lactamase sulfhydryl reagent variable |

| blaGES | Beta-lactamase Guiana extended-spectrum |

| BL/BLI | Beta-Lactam/Beta-Lactamase Inhibitor |

| CAP | Community-acquired pneumonia |

| CarO | Carbapenem-Associated outer membrane protein O |

| CFDC | Cefiderocol |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CMY | Cephamycin |

| CraA | Chloramphenicol Resistance Acinetobacter |

| CRAB | Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii |

| CREDIBLE-CR | Ceftazidime–Avibactam in the Treatment of Serious Infections due to Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| ESBL | Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase |

| EUCAST | European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing |

| FOX | Forkhead box protein |

| gyrA | DNA gyrase subunit A |

| gyrB | DNA gyrase subunit B |

| HAP | Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia |

| HD-TGC | High-dose Tigecycline |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| IMP | Imipenemase |

| IS | Insertion Sequence |

| ISAba1 | Insertion Sequence Aba1 |

| KPC | Klebsiella pneumoniae Carbapenemase |

| LPS | Lipopolysaccharide |

| MATE | Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion |

| MBLs | Metallo-β-lactamases |

| MDR | Multidrug-Resistant |

| MFS | Major Facilitator Superfamily |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| MLST | Multilocus Sequence Typing |

| NDM | New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase |

| OmpA | Outer Membrane Protein A |

| Omp33-36 | Outer membrane porin 33–36 kDa |

| OprD | Outer membrane porin D |

| OXA | Oxacillinase |

| parC | Topoisomerase IV subunit A gene |

| parE | Topoisomerase IV subunit B gene |

| PBPs | Penicillin-binding proteins |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| PDR | Pandrug resistance |

| PK/PD | Pharmacokinetics / Pharmacodynamics |

| QRDRs | Quinolone resistance-determining regions |

| RND | Resistance Nodulation Division |

| SHV | Sulfhydryl variable |

| SUL–DUR | Sulbactam–durlobactam |

| TEM | Temoneira β-lactamase |

| VAP | Ventilator-associated pneumonia |

| VIM | Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase |

| WHO | World Health Organisation |

| XDR | Extensively drug-resistant |

| WGS | Whole Genome Sequencing |

| VITEK 2 | Automated identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing system |

References

- Buchhorn De Freitas, S.; Hartwig, D.D. Promising targets for immunotherapeutic approaches against Acinetobacter baumannii. Microb. Pathog. 2022, 173, 105855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piperaki, E.T.; Tzouvelekis, L.S.; Miriagou, V.; Daikos, G.L. Carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: In pursuit of an effective treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santajit, S.; Indrawattana, N. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance in ESKAPE Pathogens. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 2016, 2475067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. WHO Updates List of Drug-Resistant Bacteria Most Threatening to Human Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/17-05-2024-who-updates-list-of-drug-resistant-bacteria-most-threatening-to-human-health (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Boutzoukas, A.; Doi, Y. The global epidemiology of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miftode, I.L.; Pasare, M.A.; Miftode, R.S.; Nastase, E.; Plesca, C.E.; Lunca, C.; Miftode, E.G.; Timpau, A.S.; Iancu, L.S.; Dorneanu, O.S. What Doesn’t Kill Them Makes Them Stronger: The Impact of the Resistance Patterns of Urinary Enterobacterales Isolates in Patients from a Tertiary Hospital in Eastern Europe. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miftode, I.L.; Leca, D.; Miftode, R.S.; Roşu, F.; Plesca, C.; Loghin, I.; Timpau, A.S.; Mitu, I.; Mititiuc, I.; Dorneanu, O.; et al. The Clash of the Titans: COVID-19, Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales, and First mcr-1-Mediated Colistin Resistance in Humans in Romania. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, D.; Nielsen, T.B.; Bonomo, R.A.; Pantapalangkoor, P.; Luna, B.; Spellberg, B. Clinical and Pathophysiological Overview of Acinetobacter Infections: A Century of Challenges. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2017, 30, 409–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangel, K.; De-Simone, S.G. Treatment and Management of Acinetobacter Pneumonia: Lessons Learned from Recent World Event. Infect. Drug Resist. 2024, 17, 507–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filho, S.P.F.; Pereira, M.S.; Nobre Rodrigues, J.L.; Guimarães, R.B.; Ribeiro da Cunha, A.; Corrente, J.E.; Pignatari, A.C.C.; Fortaleza, C.M.C.B. Seasonality and weather dependance of Acinetobacter baumannii complex bloodstream infections in different climates in Brazil. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0255593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dexter, C.; Murray, G.L.; Paulsen, I.T.; Peleg, A.Y. Community-acquired Acinetobacter baumannii: Clinical characteristics, epidemiology and pathogenesis. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2015, 13, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollner-Schwetz, I.; Zechner, E.; Ullrich, E.; Luxner, J.; Pux, C.; Pichler, G.; Schippinger, W.; Krause, R.; Leitner, E. Colonization of long term care facility patients with MDR-Gram-negatives during an Acinetobacter baumannii outbreak. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2017, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayobami, O.; Willrich, N.; Harder, T.; Okeke, I.N.; Eckmanns, T.; Markwart, R. The incidence and prevalence of hospital-acquired (carbapenem-resistant) Acinetobacter baumannii in Europe, Eastern Mediterranean and Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2019, 8, 1747–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S.E.; Villedieu, A.; Bagdasarian, N.; Karah, N.; Teare, L.; Elamin, W.F. Control and management of multidrug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: A review of the evidence and proposal of novel approaches. Infect. Prev. Pract. 2020, 2, 100077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Bacterial Priority Pathogens List, 2024: Bacterial Pathogens of Public Health Importance to Guide Research, Development and Strategies to Prevent and Control Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240093461 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, G.; Miao, F.; Huang, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, X. Insights into the epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical outcomes of carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii infections in critically ill children. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1282413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathoor, N.N.; Ganesh, P.S.; Gopal, R.K. Understanding the prevalence, antimicrobial resistance, and public health challenges of Acinetobacter baumannii in India and China. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2025, 136, lxaf102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jean, S.S.; Lee, N.Y.; Tang, H.J.; Lu, M.C.; Ko, W.C.; Hsueh, P.R. Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Infections: Taiwan Aspects. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, C.L.; Anderson, M.T.; Mobley, H.L.T.; Bachman, M.A. Pathogenesis of Gram-Negative Bacteremia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-López, F.; Martínez-Meléndez, A.; Morfin-Otero, R.; Rodriguez-Noriega, E.; Maldonado-Garza, H.J.; Garza-González, E. Efficacy and In Vitro Activity of Novel Antibiotics for Infections With Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 884365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayobami, O.; Willrich, N.; Suwono, B.; Eckmanns, T.; Markwart, R. The epidemiology of carbapenem-non-susceptible Acinetobacter species in Europe: Analysis of EARS-Net data from 2013 to 2017. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control. 2020, 9, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beig, M.; Parvizi, E.; Navidifar, T.; Bostanghadiri, N.; Mofid, M.; Golab, N.; Sholeh, M. Geographical mapping and temporal trends of Acinetobacter baumannii carbapenem resistance: A comprehensive meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0311124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rashed, N.; Bindayna, K.M.; Shahid, M.; Saeed, N.K.; Darwish, A.; Joji, R.M.; Al-Mahmeed, A. Prevalence of Carbapenemases in Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates from the Kingdom of Bahrain. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healthcare-Associated Infections Acquired in Intensive Care Units—Annual Epidemiological Report for 2021. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/healthcare-associated-infections-acquired-intensive-care-units-annual-0 (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Pană, A.G.; Șchiopu, P.; Țoc, D.A.; Neculicioiu, V.S.; Butiuc-Keul, A.; Farkas, A.; Dobrescu, M.; Flonta, M.; Costache, C.; Szász, I.É.; et al. Clonality and the Phenotype–Genotype Correlation of Antimicrobial Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii Isolates: A Multicenter Study of Clinical Isolates from Romania. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borcan, A.M.; Rotaru, E.; Caravia, L.G.; Filipescu, M.C.; Simoiu, M. Trends in Antimicrobial Resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa from Bloodstream Infections: An Eight-Year Study in a Romanian Tertiary Hospital. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lăzureanu, V.; Poroșnicu, M.; Gândac, C.; Moisil, T.; Bădițoiu, L.; Laza, R.; Marinescu, A.R. Infection with Acinetobacter baumannii in an intensive care unit in the Western part of Romania. BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gheorghe-Barbu, I.; Barbu, I.C.; Popa, L.I.; Pîrcălăbioru, G.G.; Popa, M.; Măruțescu, L.; Niță-Lazar, M.; Banciu, A.; Stoica, C.; Gheorghe, Ș.; et al. Temporo-spatial variations in resistance determinants and clonality of Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains from Romanian hospitals and wastewaters. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancuso, G.; Midiri, A.; Gerace, E.; Biondo, C. Bacterial Antibiotic Resistance: The Most Critical Pathogens. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaiskos, I.; Lagou, S.; Pontikis, K.; Rapti, V.; Poulakou, G. The “Old” and the “New” Antibiotics for MDR Gram-Negative Pathogens: For Whom, When, and How. Front. Public Health 2019, 7, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, C.M.; Hennon, S.W.; Feldman, M.F. Uncovering the mechanisms of Acinetobacter baumannii virulence. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Černiauskienė, K.; Dambrauskienė, A.; Vitkauskienė, A. Associations between β-Lactamase Types of Acinetobacter baumannii and Antimicrobial Resistance. Medicina 2023, 59, 1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kornelsen, V.; Kumar, A. Update on Multidrug Resistance Efflux Pumps in Acinetobacter spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2021, 65, e0051421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choquet, M.; Lohou, E.; Pair, E.; Sonnet, P.; Mullié, C. Efflux Pump Overexpression Profiling in Acinetobacter baumannii and Study of New 1-(1-Naphthylmethyl)-Piperazine Analogs as Potential Efflux Inhibitors. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2023, 65, e00710-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, L.; Li, J.; Peng, Q.; Liu, X.; Lin, F.; Dai, X.; Ling, B. Contribution of RND superfamily multidrug efflux pumps AdeABC, AdeFGH, and AdeIJK to antimicrobial resistance and virulence factors in multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii AYE. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2025, 69, e01858-24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarshar, M.; Behzadi, P.; Scribano, D.; Palamara, A.T.; Ambrosi, C. Acinetobacter baumannii: An Ancient Commensal with Weapons of a Pathogen. Pathogens 2021, 10, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, M.A.; Salim, M.T.A.; Anwer, B.E.; Aboshanab, K.M.; Aboulwafa, M.M. Impact of target site mutations and plasmid associated resistance genes acquisition on resistance of Acinetobacter baumannii to fluoroquinolones. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manik, M.R.K.; Mishu, I.D.; Mahmud, Z.; Muskan, M.N.; Emon, S.Z. Association of fluoroquinolone resistance with rare quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) mutations and protein-quinolone binding affinity (PQBA) in multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli isolated from patients with urinary tract infection. J. Infect. Public Health 2025, 18, 102766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maan, L.; Anand, N.; Yadav, G.; Mishra, M.; Gupta, M.K. The Efficacy and Safety of Intravenous Colistin Plus Aerosolized Colistin Versus Intravenous Colistin Alone in Critically Ill Trauma Patients With Multi-Drug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacilli Infection. Cureus 2021, 15, e49314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Cui, X.; Jiang, M.; Huang, S.; Yang, M. Nebulized colistin as the adjunctive treatment for ventilator-associated pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Crit. Care 2023, 77, 154315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, C.H.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, H.T.; Park, K.J.; Wi, Y.M. Ineffectiveness of colistin monotherapy in treating carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Pneumonia: A retrospective single-center cohort study. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Fu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Y.; Fan, X.; Yu, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. The efficacy of colistin monotherapy versus combination therapy with other antimicrobials against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii ST2 isolates. J. Chemother. 2020, 32, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, M.; Chen, K.; Chan, E.W.C.; Chen, S. Synergistic Antimicrobial Effect of Colistin in Combination with Econazole against Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and Its Persisters. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0093722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostanghadiri, N.; Narimisa, N.; Mirshekar, M.; Dadgar-Zankbar, L.; Taki, E.; Navidifar, T.; Darban-Sarokhalil, D. Prevalence of colistin resistance in clinical isolates of Acinetobacter baumannii: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2024, 13, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T.; Yamawaki, K. Cefiderocol: Discovery, Chemistry, and In Vivo Profiles of a Novel Siderophore Cephalosporin. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 69, S538–S543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, A.; Sato, T.; Ota, M.; Takemura, M.; Nishikawa, T.; Toba, S.; Yamano, Y. In Vitro Antibacterial Properties of Cefiderocol, a Novel Siderophore Cephalosporin, against Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 62, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, M.; Echols, R.; Matsunaga, Y.; Ariyasu, M.; Doi, Y.; Ferrer, R.; Lodise, T.P.; Naas, T.; Niki, Y.; Paterson, D.L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of cefiderocol or best available therapy for the treatment of serious infections caused by carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (CREDIBLE-CR): A randomised, open-label, multicentre, pathogen-focused, descriptive, phase 3 trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fritzenwanker, M.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Herold, S.; Wagenlehner, F.M.; Zimmer, K.P.; Chakraborty, T. Treatment Options for Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Dtsch. Ärzteblatt Int. 2018, 115, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Qin, W.; Zheng, Y.; Cao, D.; Lu, H.; Zhang, L.; Cui, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, W.; Guo, H.; et al. High-Dose versus Standard-Dose Tigecycline Treatment of Secondary Bloodstream Infections Caused by Extensively Drug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: An Observational Cohort Study. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 3837–3848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, X.R.; Wang, Z.Z.; Li, W.C.; Wang, Y.G.; Lou, R.; Qu, X.; Zhang, L. Clinical efficacy and safety of tigecycline based on therapeutic drug monitoring for carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacterium pneumonia in intensive care units. BMC Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, C.; Yang, X.; Lu, J.; Mo, Q.; Cai, Z.; Zhu, W. Efficacy and safety of tigecycline doses for ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by multiple resistant bacteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Med. Sci. 2023, 21, 883–888. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, K.Y.; Peng, C.K.; Sheu, C.C.; Lin, Y.C.; Chan, M.C.; Wang, S.H.; T-CARE (Taiwan Critical Care and Infection) Group. Clinical effectiveness of tigecycline in combination therapy against nosocomial pneumonia caused by CR-GNB in intensive care units: A retrospective multi-centre observational study. J. Intensive Care 2023, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Jin, Y.; Ko, K.S. Effect of colistin-tigecycline combination on colistin-resistant and carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae and Acinetobacter baumannii. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0202124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, C.; Yu, Y.; Hua, X. Resistance mechanisms of tigecycline in Acinetobacter baumannii. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1141490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwazzeh, M.J.; Algazaq, J.; Al-Salem, F.A.; Alabkari, F.; Alwarthan, S.M.; Alhajri, M.; AlShehail, B.M.; Alnimr, A.; Alrefaai, A.W.; Alsaihati, F.H.; et al. Mortality and clinical outcomes of colistin versus colistin-based combination therapy for infections caused by Multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii in critically ill patients. BMC Infect. Dis. 2025, 25, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.M.; Yang, K.S.; Chung, Y.S.; Lee, K.B.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, S.B.; Yoon, Y.K. Clinical Outcomes and Safety of Meropenem-Colistin versus Meropenem-Tigecycline in Patients with Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Pneumonia. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, I.; Tang, T. Colistin Monotherapy versus Colistin plus Meropenem Combination Therapy for the Treatment of Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Infection: A Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante-Mangonim, E.; Andini, R.; Zampino, R. Management of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 943–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sader, H.S.; Castanheira, M.; Jones, R.N.; Flamm, R.K. Antimicrobial activity of ceftazidime-avibactam and comparator agents when tested against bacterial isolates causing infection in cancer patients (2013–2014). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 87, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacconelli, E.; Carrara, E.; Savoldi, A.; Harbarth, S.; Mendelson, M.; Monnet, D.L.; Pulcini, C.; Kahlmeter, G.; Kluytmans, J.; Carmeli, Y.; et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: The WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 318–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papp-Wallace, K.M.; Mack, A.R.; Taracila, M.A.; Bonomo, R.A. Resistance to Novel β-Lactam–β-Lactamase Inhibitor Combinations. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2020, 34, 773–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Aitken, S.L.; Bonomo, R.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Van Duin, D.; Clancy, C.J. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2023 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, ciad428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S.M.; Carter, N.M.; Bradford, P.A.; Miller, A.A. In vitro antibacterial activity of sulbactam–durlobactam in combination with other antimicrobial agents against Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 109, 116344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Findlay, J.; Poirel, L.; Bouvier, M.; Nordmann, P. In vitro activity of sulbactam–durlobactam against carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii and mechanisms of resistance. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2022, 30, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaye, K.S.; Shorr, A.F.; Wunderink, R.G.; Du, B.; Poirier, G.E.; Rana, K.; Miller, A.; Lewis, D.; O’Donnell, J.; Chen, L.; et al. Efficacy and safety of sulbactam–durlobactam versus colistin for the treatment of patients with serious infections caused by Acinetobacter baumannii-calcoaceticus complex: A multicentre, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3, non-inferiority clinical trial (ATTACK). Lancet Infect. Dis. 2023, 23, 1072–1084. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO. Guidelines for the Prevention and Control of Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Health Care Facilities (WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493061/ (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Wong, S.C.; Chau, P.H.; So, S.Y.C.; Lam, G.K.M.; Chan, V.W.M.; Yuen, L.L.H.; Cheng, V.C.C. Control of Healthcare-Associated Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii by Enhancement of Infection Control Measures. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelemen, J.; Sztermen, M.; Dakos, E.K.; Budai, J.; Katona, J.; Szekeressy, Z.; Sipos, L.; Papp, Z.; Stercz, B.; Dunai, Z.A.; et al. Complex Infection-Control Measures with Disinfectant Switch Help the Successful Early Control of Carbapenem-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Outbreak in Intensive Care Unit. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foucrier, A.; Roquilly, A.; Bachelet, D.; Martin-Loeches, I.; Bougle, A.; Timsit, J.F.; Montravers, P.; Zahar, J.-R.; Eloy, P.; Weiss, E.; et al. Antimicrobial Stewardship for Ventilator Associated Pneumonia in Intensive Care (the ASPIC trial): Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e065293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Region/Context | No. of Isolates | Methodology/Testing | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multicenter (Romania, 2025) | 142 clinical isolates from 6 hospitals | Phenotypic AST (EUCAST); genotyping by PCR and WGS | Approximately 91.5% of A. baumannii isolates were extensively drug-resistant and carbapenem-resistant (XDR-CRAB). The predominant genes were bla_OXA-23-like (91.5%), bla_OXA-24/40-like (74.6%), and ArmA (63.6%) [25]. |

| Bucharest (Tertiary Infectious Disease Hospital, 2017–2024) | 289 bloodstream isolates | Automated susceptibility testing (VITEK 2) | Bloodstream isolates of A. baumannii showed 100% resistance to carbapenems and aminoglycosides by 2024; overall MDR prevalence ≈ 90.7% [26]. |

| Western Romania (ICU, Timișoara, 2011–2015) | 185 ICU isolates | Disk diffusion (CLSI); confirmatory E-test | A. baumannii isolates exhibited 94.6% resistance to both imipenem and ceftazidime; 81.1% to ampicillin/sulbactam [27]. |

| Clinical and Environmental Isolates (2018–2019) | 70 clinical + 28 wastewater isolates | Phenotypic AST + PCR for resistance genes | Both hospital and wastewater A. baumannii isolates carried multiple resistance genes (bla_OXA-23, bla_OXA-24, bla_SHV, bla_TEM, bla_GES), suggesting cross-contamination between hospitals and environment [28]. |

| Class | Enzyme Type | Mechanism | Example Enzymes | Inhibition by β-Lactamase Inhibitors? | Found in A. baumannii |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Serine β-lactamase | Hydrolyzes via serine site | KPC, TEM, SHV | Yes | Occasional (ESBL TEM/SHV); KPC very rare |

| B | Metallo-β-lactamase | Zinc-dependent hydrolysis | NDM, VIM, IMP | Limited/variable | Common (intrinsic ADC) |

| C | AmpC cephalosporinase | Chromosomal or plasmidic cephalosporinase | CMY, FOX | Limited/variable | Rare |

| D | Oxacillinases (OXA) | Hydrolyzes oxacillin and carbapenems | OXA-23, OXA-24/40, OXA-58, OXA-51 like | Limited/variable | Common |

| Carbapenemase [Gene] | Carbapenem Activity | Prevalence | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OXA-23 | High | Global, high in Asia and Europe | Most prevalent; often associated with ISAba1 insertions |

| OXA-24/40 | Moderate to High | Europe, sporadic elsewhere | Plasmid or chromosomal; potent but less widespread |

| OXA-58 | Variable | Outbreak-related | Frequently plasmid-mediated; involved in nosocomial outbreaks |

| OXA-51-like | Low unless upregulated | Intrinsic to all A. baumannii | Chromosomal; expression level determines resistance |

| NDM-1 [29] | Very High | Emerging globally, rare in A. baumannii | Requires zinc; not inhibited by classical inhibitors |

| Efflux Pump System | Superfamily | Genes Involved | Antibiotics Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| AdeABC [34,35] | RND | adeA, adeB, adeC | Aminoglycosides, β-lactams, fluoroquinolones, tigecycline |

| AdeIJK [34,35] | RND | adeI, adeJ, adeK | Chloramphenicol, tetracycline, fluoroquinolones |

| AdeFGH [34,35] | RND | adeF, adeG, adeH | Chloramphenicol, tigecycline, trimethoprim |

| CraA [34] | MFS | craA | Chloramphenicol |

| AmvA [34] | MFS | amvA | Disinfectants, dyes |

| AbeM [34] | MATE | abeM | Fluoroquinolones, gentamicin |

| Porin | Function | Resistance Mechanism | Antibiotics Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| OmpA [36] | Structural OMP; adhesion and biofilm | Minor role in permeability and biofilm-related tolerance | Multiple, including β-lactams |

| Omp33–36 [9] | Non-specific diffusion channel | Downregulation reduces β-lactam and carbapenem influx | Carbapenems, cephalosporins |

| CarO [36] | Facilitates imipenem uptake | Gene disruption or mutation leads to decreased permeability | Primarily imipenem |

| OprD [9] | Basic amino acids/antibiotic uptake | Often altered or downregulated in resistant strains | Carbapenems (primarily described in Pseudomonas aeruginosa; evidence in A. baumannii is limited) |

| Antibiotic/Combination | Mechanism of Action | MIC Range [µg/mL] | Level of Evidence | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colistin (Polymyxin E) | Disrupts bacterial membranes | 0.5–2 (susceptible) | Moderate (observational, in vitro) | Nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity |

| Tigecycline | Inhibits protein synthesis (30S ribosome) | 0.25–2 (variable) | Low (retrospective studies) | Nausea, vomiting, hepatotoxicity |

| Carbapenems (e.g., meropenem) | Inhibits cell wall synthesis | >8 (often resistant) | Moderate (clinical practice, guidelines) | Seizures (especially imipenem), nephrotoxicity |

| Cefiderocol | Siderophore cephalosporin | 0.12–4 | High (clinical trials) | Diarrhea, infusion site reactions |

| Sulbactam–Durlobactam | β-lactamase inhibitor + β-lactam | 1–4 | High (Phase 3 trials) | Mild gastrointestinal disturbances |

| Ampicillin–Sulbactam | Cell wall inhibition + β-lactamase block | 2–8 | Moderate (clinical use) | Hepatotoxicity, rash |

| Ceftazidime–Avibactam | Cephalosporin + β-lactamase inhibitor | >16 | Low (limited studies for A. baumannii) | Hypersensitivity, diarrhea |

| Polymyxin B | Similar to colistin | 0.25–2 | Moderate (clinical use, observational) | Nephrotoxicity, neurotoxicity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Stoian, I.A.; Balas Maftei, B.; Florea, C.-E.; Rotaru, A.; Costin, C.A.; Pasare, M.A.; Crisan Dabija, R.; Manciuc, C. Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Resistance Mechanisms, Emerging Therapies, and Prevention—A Narrative Review. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010002

Stoian IA, Balas Maftei B, Florea C-E, Rotaru A, Costin CA, Pasare MA, Crisan Dabija R, Manciuc C. Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Resistance Mechanisms, Emerging Therapies, and Prevention—A Narrative Review. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleStoian, Ioana Adelina, Bianca Balas Maftei, Carmen-Elena Florea, Alexandra Rotaru, Constantin Aleodor Costin, Maria Antoanela Pasare, Radu Crisan Dabija, and Carmen Manciuc. 2026. "Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Resistance Mechanisms, Emerging Therapies, and Prevention—A Narrative Review" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010002

APA StyleStoian, I. A., Balas Maftei, B., Florea, C.-E., Rotaru, A., Costin, C. A., Pasare, M. A., Crisan Dabija, R., & Manciuc, C. (2026). Multidrug-Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii: Resistance Mechanisms, Emerging Therapies, and Prevention—A Narrative Review. Antibiotics, 15(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010002