β,β-Dimethylacrylalkannin Restores Colistin Efficacy Against mcr- and TCS-Mediated Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria via Membrane Disturbance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. β,β-Dim Is Identified as a Potential Colistin Adjuvant Through High-Throughput Screening

2.2. β,β-Dim Enhances Colistin Efficacy by Inhibiting LPS Transport and Efflux Pump Activity, and by Increasing Intracellular Colistin Accumulation

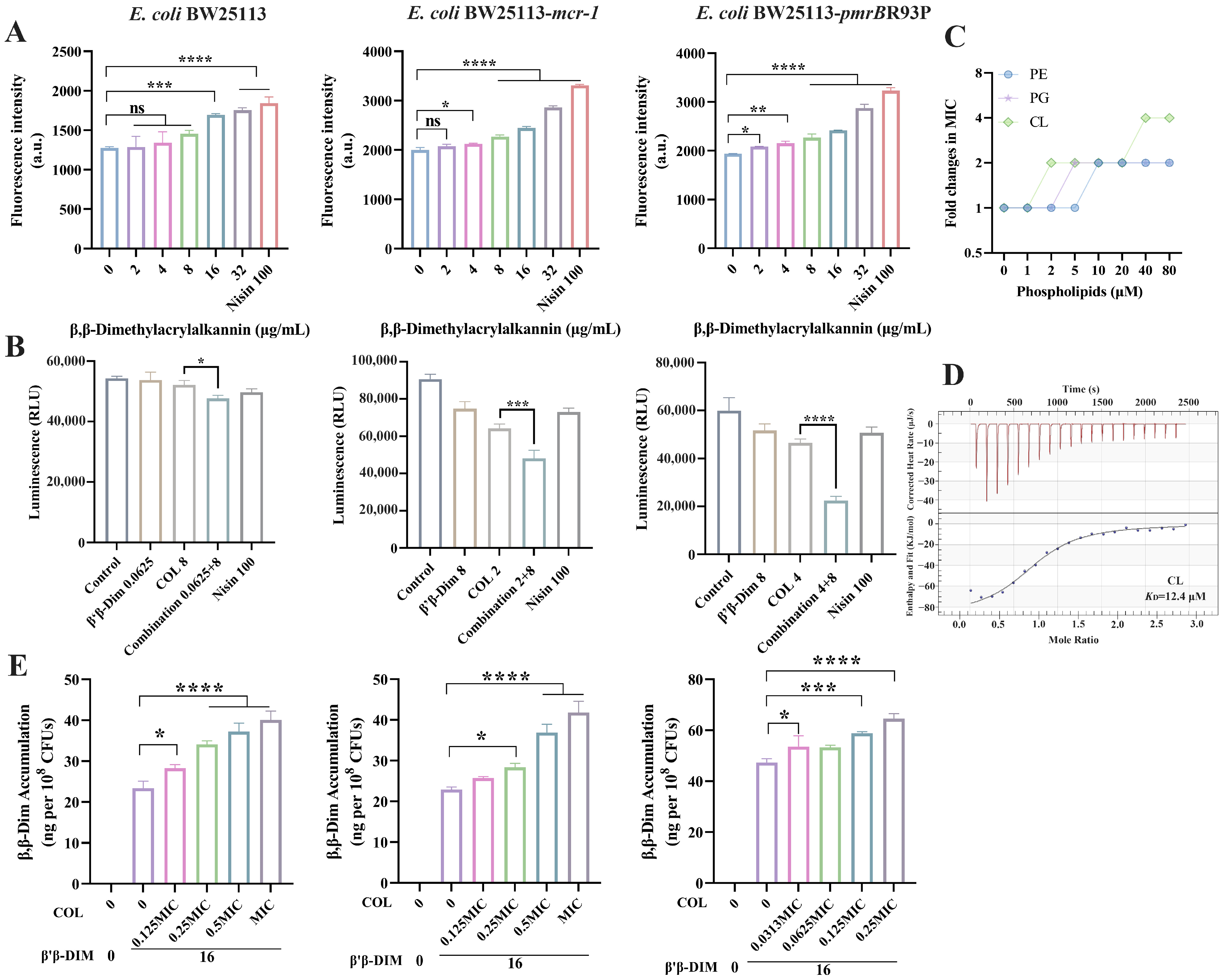

2.3. β,β-Dim Disrupts Biofunction of Cytoplasmic Membrane by Targeting Phospholipids

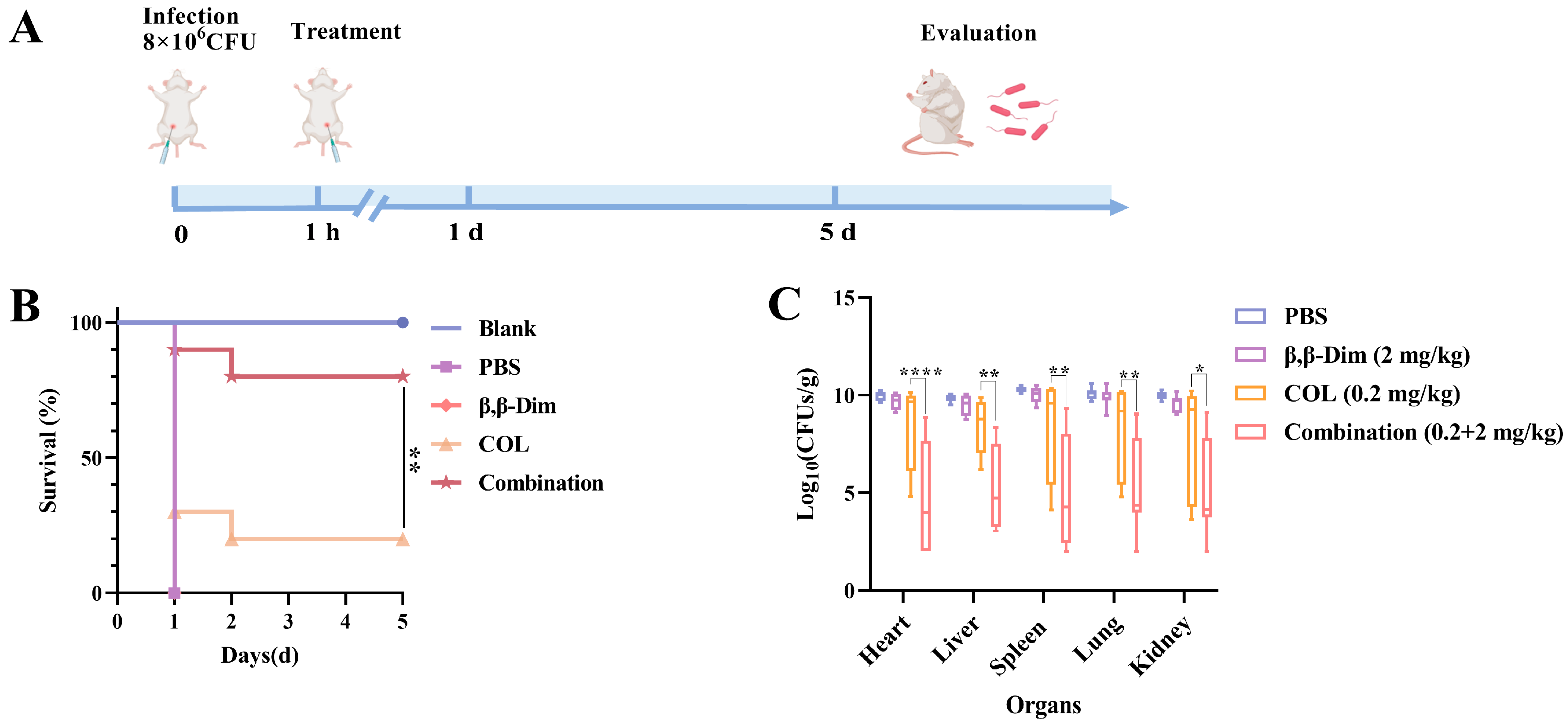

2.4. β,β-Dim Enhances Colistin’s Therapeutic Efficiency In Vivo

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Compounds, Antibiotics, and Mice

4.2. Cell-Based Screening

4.3. Toxicity Assay

4.4. Checkerboard Assay

4.5. Antibacterial Activity

4.6. Transcriptome Analysis

4.7. LptD Expression

4.8. Determination of LPS Concentrations

4.9. Efflux Pump Activity

4.10. Intracellular Compound Content Determination

4.11. ROS Determination

4.12. Membrane Permeability Determination

4.13. Effect of Membrane Components on Antibacterial Activity

4.14. ATP Determination

4.15. Murine Abdominal Infection Model

4.16. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, J.-H.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Shen, Y.-B.; Yang, J.; Walsh, T.R.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J. Plasmid-mediated colistin-resistance genes: Mcr. Trends Microbiol. 2024, 32, 365–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Sayed Ahmed, M.A.E.-G.; Zhong, L.-L.; Shen, C.; Yang, Y.; Doi, Y.; Tian, G.-B. Colistin and its role in the Era of antibiotic resistance: An extended review (2000–2019). Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 868–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; Zou, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, R.; Liu, D.; Wu, C.; Shen, J.; et al. Anticancer agent 5-fluorouracil reverses meropenem resistance in carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandler, M.D.; Baidin, V.; Lee, J.; Pahil, K.S.; Owens, T.W.; Kahne, D. Novobiocin Enhances Polymyxin Activity by Stimulating Lipopolysaccharide Transport. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6749–6753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wistrand-Yuen, P.; Olsson, A.; Skarp, K.-P.; Friberg, L.E.; Nielsen, E.I.; Lagerbäck, P.; Tängdén, T. Evaluation of polymyxin B in combination with 13 other antibiotics against carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in time-lapse microscopy and time-kill experiments. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1214–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, M.; Zou, Z.; Yang, S.; Yi, T.; Wang, J.; Liu, D.; Shen, Y.; Dai, C.; et al. Dual Effects of Feed-Additive-Derived Chelerythrine in Combating Mobile Colistin Resistance. Engineering 2024, 32, 163–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, B.; Chu, X.; Su, J.; Xu, L.; Li, L.; Deng, X.; Li, D.; Lv, Q.; Wang, J. Commercialized artemisinin derivatives combined with colistin protect against critical Gram-negative bacterial infection. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hondros, A.D.; Young, M.M.; Jaimes, F.E.; Kinkead, J.; Thompson, R.J.; Melander, C.; Cavanagh, J. Two-Component System Sensor Kinase Inhibitors Target the ATP-Lid of PmrB to Disrupt Colistin Resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii. Biochemistry 2025, 64, 1317–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoaiter, M.; Zeaiter, Z.; Mediannikov, O.; Sokhna, C.; Fournier, P.-E. Carbonyl Cyanide 3-Chloro Phenyl Hydrazone (CCCP) Restores the Colistin Sensitivity in Brucella intermedia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Han, H.; Wu, C.; Li, Q.; Hu, H.; Liu, W.; Shi, D.; Chen, F.; Lan, L.; Li, J.; et al. Discovery of a novel polymyxin adjuvant against multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacteria through oxidative stress modulation. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2025, 15, 1680–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colclough, A.; Corander, J.; Sheppard, S.K.; Bayliss, S.C.; Vos, M. Patterns of cross-resistance and collateral sensitivity between clinical antibiotics and natural antimicrobials. Evol. Appl. 2019, 12, 878–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Jia, P.; Li, X.; Jia, X.; Yu, W.; Cui, Y.; Yang, R.; Xia, W.; et al. Emergence of colistin-resistant hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae (CoR-HvKp) in China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2022, 11, 648–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.-L.; Guo, Y.-Z.; Wu, Y.-M.; Gong, W.-T.; Sun, J.; Huang, Z. In vivo bactericidal effect of colistin-linezolid combination in a murine model of MDR and XDR Acinetobacter baumannii pneumonia. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Liu, Y.; Li, T.; Liu, X.; Hao, Z.; Ding, S.; Panichayupakaranant, P.; Zhu, K.; Shen, J. Plant Natural Flavonoids Against Multidrug Resistant Pathogens. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, e2100749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmi, P.; Pontecorvi, V.; Rotondi, G. Natural compounds and extracts as novel antimicrobial agents. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2020, 30, 949–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Tang, X.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, C. Structural insight into lipopolysaccharide transport from the Gram-negative bacterial inner membrane to the outer membrane. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2017, 1862, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabnis, A.; Hagart, K.L.; Klöckner, A.; Becce, M.; Evans, L.E.; Furniss, R.C.D.; Mavridou, D.A.; Murphy, R.; Stevens, M.M.; Davies, J.C.; et al. Colistin kills bacteria by targeting lipopolysaccharide in the cytoplasmic membrane. eLife 2021, 10, e65836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beggs, G.A.; Brennan, R.G.; Arshad, M. MarR family proteins are important regulators of clinically relevant antibiotic resistance. Protein Sci. 2020, 29, 647–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaramoorthy, N.S.; Suresh, P.; Selva Ganesan, S.; GaneshPrasad, A.; Nagarajan, S. Restoring colistin sensitivity in colistin-resistant E. coli: Combinatorial use of MarR inhibitor with efflux pump inhibitor. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.L.; Anderson, M.T.; Mobley, H.L.T.; Bachman, M.A. Pathogenesis of Gram-Negative Bacteremia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2021, 34, e00234-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, S.; Willcox, M.D.P.; Rayamajhee, B. A Review of Resistance to Polymyxins and Evolving Mobile Colistin Resistance Gene (mcr) among Pathogens of Clinical Significance. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.R.; Zakaria, Z.; Hassan, L.; Mohd Faiz, N.; Ahmad, N.I. Antimicrobial Resistance Profiles and Co-Existence of Multiple Antimicrobial Resistance Genes in mcr-Harbouring Colistin-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae Isolates Recovered from Poultry and Poultry Meats in Malaysia. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Cai, J.; Shi, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y. Resensitizing multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria to carbapenems and colistin using disulfiram. Commun. Biol. 2023, 6, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Liu, J.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, W.; Efferth, T.; Liu, S.; Hua, X. Cajanin stilbene acid: A direct inhibitor of colistin resistance protein MCR-1 that restores the efficacy of polymyxin B against resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Phytomedicine 2023, 114, 154803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Liu, Y.; Huang, X.; Ding, S.; Wang, Y.; Shen, J.; Zhu, K. A broad-spectrum antibiotic adjuvant reverses multidrug-resistant Gram-negative pathogens. Nat. Microbiol. 2020, 5, 1040–1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guducuoglu, H.; Gursoy, N.C.; Yakupogullari, Y.; Parlak, M.; Karasin, G.; Sunnetcioglu, M.; Otlu, B. Hospital Outbreak of a Colistin-Resistant, NDM-1- and OXA-48-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: High Mortality from Pandrug Resistance. Microb. Drug Resist. 2018, 24, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jin, R. DFT study on the radical scavenging activity of β,β-dimethylacrylalkannin derivatives. Mol. Simul. 2012, 38, 980–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Huang, Y.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Meng, C.; Wang, Z. Acetylshikonin Derived From Arnebia euchroma (Royle) Johnst Kills Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Positive Pathogens In Vitro and In Vivo. Phytother. Res. 2025, 39, 1372–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, M.; Saitis, T.; Shareef, R.; Harb, C.; Lakhani, M.; Ahmad, Z. Shikonin and Alkannin inhibit ATP synthase and impede the cell growth in Escherichia coli. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, R.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.; Meng, C.; Xiao, X. Acetylshikonin reduces the spread of antibiotic resistance via plasmid conjugation. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plyta, Z.F.; Li, T.; Papageorgiou, V.P.; Mellidis, A.S.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Pitsinos, E.N.; Couladouros, E.A. Inhibition of topoisomerase I by naphthoquinone derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 1998, 8, 3385–3390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Rajput, A.; Kaur, H.; Sharma, A.; Bhagat, K.; Singh, J.V.; Arora, S.; Bedi, P.M.S. Shikonin derivatives as potent xanthine oxidase inhibitors: In-vitro study. Nat. Prod. Res. 2023, 37, 2795–2800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, R.; Yin, F.; Fredimoses, M.; Zhao, J.; Fu, X.; Xu, B.; Liang, M.; Chen, H.; Liu, K.; Lei, M.; et al. Targeting FGFR1 by β,β-dimethylacrylalkannin suppresses the proliferation of colorectal cancer in cellular and xenograft models. Phytomedicine 2024, 129, 155612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.-P.; Yan, X.-D.; Fan, X.-Y.; Ling, Y.-H.; Li, C.; Lin, L.; Qin, D.; Liu, T.-T.; Li, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Oral acute and chronic toxicity studies of β, β-dimethylacrylalkannin in mice and rats. Fundam. Toxicol. Sci. 2017, 4, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y.; Lee, W.; Kwa, A.L. Polymyxin B versus colistin: An update. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 2015, 13, 1481–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, Y.; Song, H.; Zhang, M.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Xia, X.; Qin, S.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; et al. β,β-Dimethylacrylalkannin Restores Colistin Efficacy Against mcr- and TCS-Mediated Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria via Membrane Disturbance. Antibiotics 2026, 15, 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010003

Liu Y, Song H, Zhang M, Jiang J, Zhang Y, Xu J, Xia X, Qin S, Shen J, Wang Y, et al. β,β-Dimethylacrylalkannin Restores Colistin Efficacy Against mcr- and TCS-Mediated Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria via Membrane Disturbance. Antibiotics. 2026; 15(1):3. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010003

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Yongqing, Huangwei Song, Muchen Zhang, Junyao Jiang, Yan Zhang, Jian Xu, Xi Xia, Shangshang Qin, Jianzhong Shen, Yang Wang, and et al. 2026. "β,β-Dimethylacrylalkannin Restores Colistin Efficacy Against mcr- and TCS-Mediated Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria via Membrane Disturbance" Antibiotics 15, no. 1: 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010003

APA StyleLiu, Y., Song, H., Zhang, M., Jiang, J., Zhang, Y., Xu, J., Xia, X., Qin, S., Shen, J., Wang, Y., & Liu, D. (2026). β,β-Dimethylacrylalkannin Restores Colistin Efficacy Against mcr- and TCS-Mediated Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria via Membrane Disturbance. Antibiotics, 15(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics15010003