Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections in the WHO African Region: Systematic Review of Literature from 2011 to 2024

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PICO Elements (Population (Or Patient/Problem), Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (Result)) [31,32]

- Population (P): the target population consists of patients receiving care in any type of health facility (university hospitals, district health centers, clinics, etc.) located in member countries of the WHO African Region.

- Intervention (I): involved the implementation of an active and continuous surveillance program for HAIs or hospital–acquired infections using epidemiological methods.

- Comparison (C): the local or national scope of the HAI surveillance methods implemented and the existence of a structured or unstructured surveillance and prevention program.

- Outcome (O): Reduction in healthcare–associated infections, prevention of antimicrobial resistance, improvement of patient safety.

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Extraction

2.5. Assessment of the Quality or Risk of Bias of Articles

3. Results

3.1. Document Research, Selection Process, and Characteristics of the Selected Studies

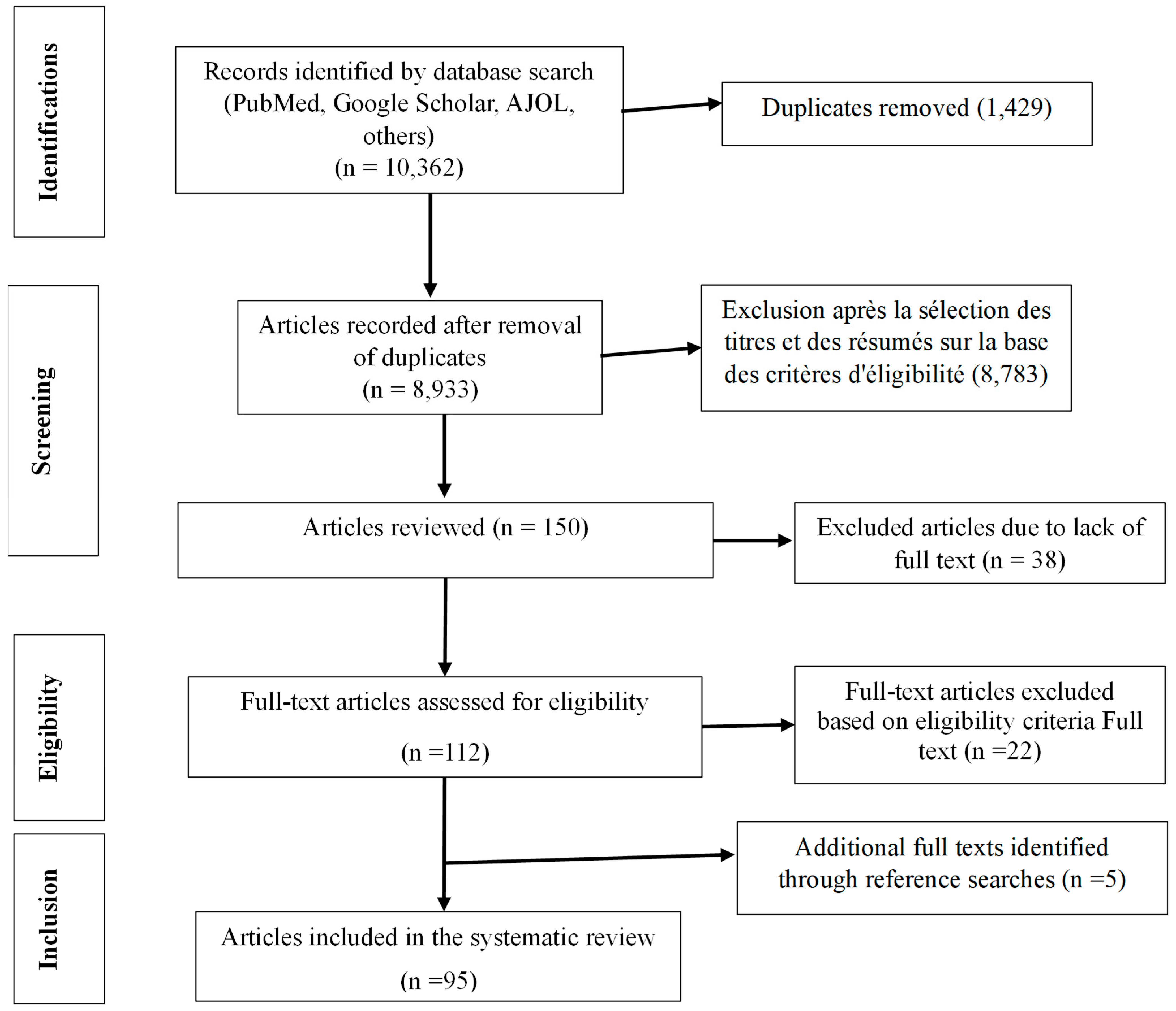

3.1.1. Document Research and Selection Process

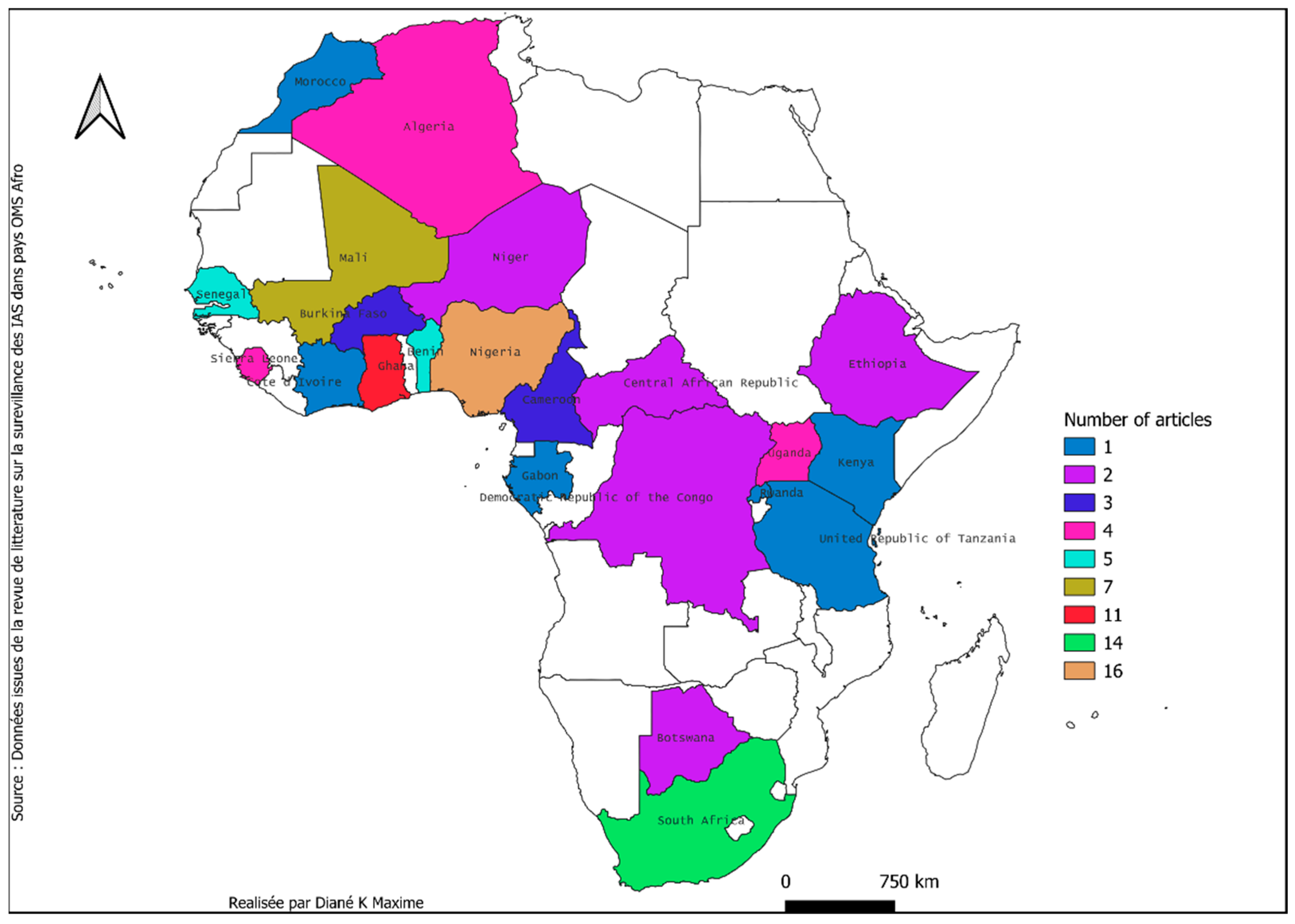

3.1.2. Characteristics of the Selected Studies

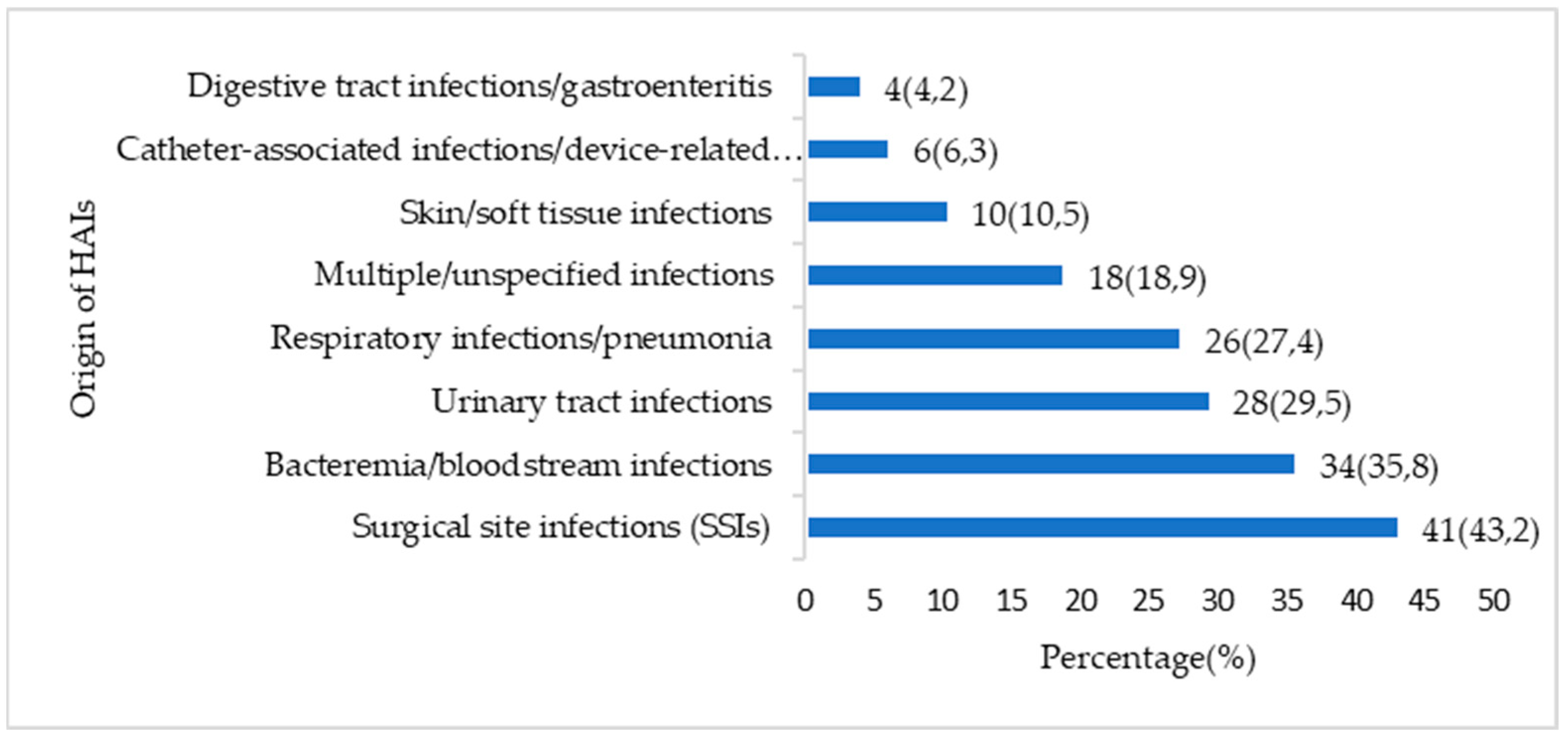

3.2. Organization of HAIs Surveillance

3.3. Reported Pathogens and Resistance Profile

3.3.1. Reported Pathogens

3.3.2. Resistance Profile

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of the Main Results

4.2. Current Status of HAI Surveillance in Africa

4.3. Heterogeneity of Monitoring Methods

4.4. Pathogens Involved in HAIs and Predominance of Multidrug–Resistant Pathogens

4.5. Laboratory Methods and Technical Limitations

4.6. Recommendation to Public Health Policies and Professionals

4.7. Recommendations for GLASS

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Registration

Abbreviations

| AST | Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test |

| C3GR | Resistance to third–generation cephalosporins |

| CASFM | Antibiogram Committee of the French Society for Microbiology |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| CRAB | Carbapenem–Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii |

| CRE | Carbapenem–Resistant Enterobacteriaceae |

| DRC | Democratic Republic of Congo |

| ESBL | Extended–spectrum beta–lactamase–producing enterobacteria |

| EUCAST | Extended Spectrum Beta–lactamases |

| GLASS | Global Surveillance System for this Resistance |

| HAI | Healthcare–Associated Infections |

| HINARI | Health InterNetwork Access to Research Initiative |

| MDR | Multidrug–Resistant Bacteria |

| Mpox | Monkeypox |

| MR | Multidrug–Resistant |

| MRSA | Methicillin–Resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| NDM | New Delhi metallo–beta–lactamase |

| NI | Nosocomial Infections |

| PICO | Population (or Patient/Problem), Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (Result) |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta–Analyses |

| R | Resistance |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoronaVirus 2 (COVID-19) |

| VRE | vancomycin–resistant enterococcus |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

References

- World Health Organization. Prevention of Hospital–Acquired Infections: A Practical Guide; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- Burke, J.P. Infection control—A problem for patient safety. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 348, 651–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, D.W.; Larizgoitia, I.; Prasopa–Plaizier, N.; Jha, A.K. Global priorities for patient safety research. BMJ 2009, 338, b1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, F.; Kraemer, P.; De Pina, J.J.; Demortiere, E.; Rapp, C. Le risque nosocomial en Afrique intertropicale–Partie 2: Les infections des patients. Med. Trop. 2007, 67, 197–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rebaudet, S.; Kraemer, P.; Savini, H.; De Pina, J.J.; Rapp, C.; Demortiere, E. Le risque nosocomial en Afrique intertropicale Partie 3: Les infections des soignants. Méd. Trop. 2007, 67, 291. [Google Scholar]

- HAS. Évaluation de la Prévention des Infections Associées Aux Soins Selon le Référentiel de Certification. 2022. Available online: https://www.has–sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2020–11/fiche_pedagogique_prevention_infection_soins_certification.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Horan, T.C.; Andrus, M.; Dudeck, M.A. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care–associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am. J. Infect. Control 2008, 36, 309–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson, C.; Kilpatrick, C.; Rasa, K.; Ren, J.; Nthumba, P.; Sawyer, R.; Ameh, E. Global surgery is stronger when infection prevention and control is incorporated: A commentary and review of the surgical infection landscape. BMC Surg. 2024, 24, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storr, J.; Twyman, A.; Zingg, W.; Damani, N.; Kilpatrick, C.; Jacqui, R.; Lesley, P.; Matthias, E.; Lindsay, G.; Kelley, E.; et al. Core components for effective infection prevention and control programmes: New WHO evidence–based recommendations. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2017, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaya, S.; Hayakawa, K.; Matsunaga, N.; Moriyama, Y.; Katanami, Y.; Tajima, T.; Tanaka, C.; Kimura, Y.; Saito, S.; Kusama, Y.; et al. Surveillance systems for healthcare–associated infection in high and upper–middle income countries: A scoping review. J. Infect. Chemother. 2020, 26, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley, R.W.; Quade, D.; Freeman, H.E.; Bennett, J.V.; The Cdc Senic Planning Commitfee. Study on the efficacy of nosocomial infection control (SENIC Project): Summary of study design. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1980, 111, 472–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F.; Demortiere, E.; Chadli, M.; Kraemer, P.; De Pina, J.J. Le risque nosocomial en Afrique intertropicale. Partie 1: Le contexte. Méd. Trop. 2006, 66, 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke, I.N.; Laxminarayan, R.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Duse, A.G.; Jenkins, P.; O’Brien, T.F.; Pablos–Mendez, A.; Klugman, K.P. Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Part I: Recent trends and current status. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellamonica, P. Antibiorésistance et maladies transmissibles [zone Afrique]. Méd. Trop. 1998, 58, 73–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, R.; Li, X.; Liu, T.; Lin, G. Effect of a real–time automatic nosocomial infection surveillance system on hospital–acquired infection prevention and control. BMC Infect. Dis. 2022, 22, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haley, R.W.; Culver, D.H.; White, J.W.; Morgan, W.M.; Emori, T.G.; van Munn, P.; Hooton, T.M. The efficacy of infection surveillance and control programs in preventing nosocomial infections in US hospitals. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1985, 121, 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittet, D.; Allegranzi, B.; Sax, H.; Bertinato, L.; Concia, E.; Cookson, B.; Fabry, J.; Richet, H.; Philip, P.; Spencer, R.C. Considerations for a WHO European strategy on health–care–associated infection, surveillance, and control. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2005, 5, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari, Y.; Yin, M.; Lim, C.; Pople, D.; Evans, S.; Stimson, J.; Pham, T.M.; Read, J.M.; Robotham, J.V.; Cooper, B.S.; et al. Effectiveness of infection prevention and control interventions, excluding personal protective equipment, to prevent nosocomial transmission of SARS–CoV–2: A systematic review and call for action. Infect. Prev. Pr. 2022, 4, 100192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamath, K.; Kumar, H.S.; Shabaraya, A.R. A comprehensive review on prevention and management of hospital–acquired infections: Current strategies and best practices. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Sci. Arch. 2023, 6, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qattan, S.Y.M.; Al Zaydan, S.M.S.; Almalki, A.A.S.; Almari, B.M.S.; Jassas, M.M.A. Nosocomial Infections: Prevention, Control and Surveillance. IJSR 2023, 2, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care: First Global Patient Safety Challenge Clean Care is Safer Care; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009; WHO Guidelines Approved by the Guidelines Review Committee. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK144013/ (accessed on 6 November 2021).

- Allegranzi, B.; Bagheri Nejad, S.; Combescure, C.; Graafmans, W.; Attar, H.; Donaldson, L.; Pittet, D. Burden of endemic health–care–associated infection in developing countries: Systematic review and meta–analysis. Lancet 2011, 377, 228–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nejad, S.B.; Allegranzi, B.; Syed, S.B.; Ellis, B.; Pittet, D. Health–care–associated infection in Africa: A systematic review. Bull. World Health Organ. 2011, 89, 757–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irek, E.O.; Amupitan, A.A.; Obadare, T.O.; Aboderin, A.O. A systematic review of healthcare–associated infections in Africa: An antimicrobial resistance perspective. Afr. J. Lab. Med. 2018, 7, 796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fraser, J.L.; Mwatondo, A.; Alimi, Y.H.; Varma, J.K.; Vilas, V.J.D.R. Healthcare–associated outbreaks of bacterial infections in Africa, 2009–2018: A review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 103, 469–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, B.T.; Ashley, E.A.; Ongarello, S.; Havumaki, J.; Wijegoonewardena, M.; González, I.J.; Dittrich, S. Antimicrobial resistance in Africa: A systematic review. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiferaw, W.S.; Aynalem, Y.A.; Akalu, T.Y.; Petrucka, P.M. Surgical site infection and its associated factors in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta–analysis. BMC Surg. 2020, 20, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malande, O.O.; Nuttall, J.; Pillay, V.; Bamford, C.; Eley, B. A ten–year review of ESBL and non–ESBL Escherichia coli bloodstream infections among children at a tertiary referral hospital in South Africa. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dramowski, A.; Madide, A.; Bekker, A. Neonatal nosocomial bloodstream infections at a referral hospital in a middle–income country: Burden, pathogens, antimicrobial resistance and mortality. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 2015, 35, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Lin, J.; Demner–Fushman, D. Evaluation of PICO as a Knowledge Representation for Clinical Questions. AMIA Annu. Symp. Proc. 2006, 2006, 359–363. [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa–Pacher, A. Research Questions with PICO: A Universal Mnemonic. Publications 2022, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, P.; Chirwa, T.; Naidoo, S.; Perovic, O.; Thomas, J. Nosocomial Outbreak of New Delhi Metallo–β–Lactamase–1–Producing Gram–Negative Bacteria in South Africa: A Case–Control Study. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0123337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, D.; Morrow, B.M.; Argent, A.C. Acinetobacter baumannii infections in a South African paediatric intensive care unit. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2015, 61, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bediako–Bowan, A.A.A.; Kurtzhals, J.A.L.; Mølbak, K.; Labi, A.K.; Owusu, E.; Newman, M.J. High rates of multi–drug resistant gram–negative organisms associated with surgical site infections in a teaching hospital in Ghana. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carshon–Marsh, R.; Squire, J.S.; Kamara, K.N.; Sargsyan, A.; Delamou, A.; Camara, B.S.; Manzi, M.; Guth, J.A.; Khogali, M.A.; Reid, A. Incidence of surgical site infection and use of antibiotics among patients who underwent caesarean section and herniorrhaphy at a regional referral hospital, Sierra Leone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landre–Peigne, C.; Ka, A.S.; Peigne, V.; Bougere, J.; Seye, M.N.; Imbert, P. Efficacy of an infection control programme in reducing nosocomial bloodstream infections in a Senegalese neonatal unit. J. Hosp. Infect. 2011, 79, 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meli, H.; Cissoko, Y.; Konaté, I.; Soumaré, M.; Fofana, A.; Dembélé, J.P.; Kaboré, M.; Cissé, M.A.; Zaré, A.; Dao, S. Co–infection tuberculose–VIH compliquée d’une sur infection nosocomiale à Klebsiella pneumoniae: À propos de 4 observations dans un Service de Maladies Infectieuses au Mali. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 37, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, S.; Thiam, I.; Fall, B.; Ba–Diallo, A.; Diallo, O.F.; Diagne, R.; Dia, M.L.; Ka, R.; Sarr, A.M.; Sow, A.I. Urinary tract infection with Corynebacterium aurimucosum after urethroplasty stricture of the urethra: A case report. J. Med. Case Rep. 2015, 9, 156. [Google Scholar]

- Moissenet, D.; Weill, F.X.; Arlet, G.; Harrois, D.; Girardet, J.P.; Vu–Thien, H. Salmonella enterica serotype Gambia with CTX–M–3 and armA resistance markers: Nosocomial infections with a fatal outcome. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 1676–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Aulakh, A.; Idoko, P.; Anderson, S.T.; Graham, W. Caesarean section wound infections and antibiotic use: A retrospective case–series in a tertiary referral hospital in The Gambia. Trop. Doct 2018, 48, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo, E.O.; Mofolorunsho, C.K.; Akande, A.O. Aetiological agents of surgical site infection in a specialist hospital in Kano, north–western Nigeria. Tanzan. J. Health Res. 2014, 16, 289–295. [Google Scholar]

- Lakoh, S.; Li, L.; Sevalie, S.; Guo, X.; Adekanmbi, O.; Yang, G.; Oladimeji, A.; Le, Y.; Joshua, M.C.; Shuchao, W.; et al. Antibiotic resistance in patients with clinical features of healthcare–associated infections in an urban tertiary hospital in Sierra Leone: A cross–sectional study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2020, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinkunmi, E.O.; Adesunkanmi, A.R.; Lamikanra, A. Pattern of pathogens from surgical wound infections in a Nigerian hospital and their antimicrobial susceptibility profiles. Afr. Health Sci. 2014, 14, 802–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehouenou, C.L.; Kpangon, A.A.; Affolabi, D.; Rodriguez–Villalobos, H.; Van Bambeke, F.; Dalleur, O.; Simon, A. Antimicrobial resistance in hospitalized surgical patients: A silently emerging public health concern in Benin. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2020, 19, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olowo–okere, A.; Ibrahim, Y.K.E.; Olayinka, B.O. Molecular characterisation of extended–spectrum β–lactamase–producing Gram–negative bacterial isolates from surgical wounds of patients at a hospital in North Central Nigeria. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018, 14, 85–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labi, A.K.; Nielsen, K.L.; Marvig, R.L.; Bjerrum, S.; Enweronu–Laryea, C.; Bennedbæk, M.; Newman, M.J.; Ayibor, P.K.; Andersen, L.P.; Kurtzhals, J.A. Oxacillinase–181 Carbapenemase–Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Ghana, 2017–2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2235–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guetarni, N.; Zouagui, S.; Besbes, F.; Derkaoui, A.; Hanba, M.; Ahmed Fouatih, Z. Infections Nosocomiales (IN): Enquête de prévalence et d’identification des facteurs de risque dans un centre hospitalier universitaire de la région ouest d’Algérie, 2016. Rev. Méd. L Hmruo 2017, 4, 584–590. [Google Scholar]

- Bayingana, C.; Sendegeya, A.; Habarugira, F.; Mukumpunga, C.; Lyumugabe, F.; Ndoli, J. Hospital acquired infections in pediatrics unit at Butare University Teaching Hospital (CHUB). Rwanda J. Med. Health Sci. 2019, 2, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolawole, O.M.; Idakwo, A.I.; Ige, O.; Anibijuwon, I.O. Prevalence of Hospital Acquired Infections in The Intensive Care Unit of University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital, Ilorin Nigeria. Sudan J. Med. Sci. 2015, 10, 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, A.; Steinberg, W.J.; Habib, T.; Saeed, H.; Raubenheimer, J.E. Prevalence of healthcare–associated infection at a tertiary hospital in the Northern Cape Province, South Africa. S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2018, 60, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanou, I.; Kabore, A.; Tapsoba, E.; Bicaba, I.; Ba, A.; Zango, B. Nosocomial Urinary Infections at the Urogoly Unit of the National University Hospital (Yalgado Ouedraogo), Ouagadougou: Feb.–Sept 2012. Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 2015, 16, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwuafor, A.A.; Ogunsola, F.T.; Oladele, R.O.; Oduyebo, O.O.; Desalu, I.; Egwuatu, C.C.; Nnachi, A.U.; Akujobi, C.N.; Ita, I.O.; Ogban, G.I. Incidence, Clinical Outcome and Risk Factors of Intensive Care Unit Infections in the Lagos University Teaching Hospital (LUTH), Lagos, Nigeria. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihla, A.J.F.T.; Ngunde, P.J.; Mbianda, S.E.; Nkwelang, G.; Ndip, R.N. Risk factors for wound infection in health care facilities in Buea, Cameroon: Aerobic bacterial pathogens and antibiogram of isolates. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2014, 18, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madu, K.A.; Enweani, U.N.; Katchy, A.U.; Madu, A.J.; Aguwa, E.N. Implant Associated Surgical Site Infection in Orthopaedics: A Regional Hospital Experience. Niger. J. Med. 2011, 20, 435–440. [Google Scholar]

- Manyahi, J.; Matee, M.I.; Majigo, M.; Moyo, S.; Mshana, S.E.; Lyamuya, E.F. Predominance of multi–drug resistant bacterial pathogens causing surgical site infections in Muhimbili National Hospital, Tanzania. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, D.; Revathi, G.; Sam, K.; Abdi, H.; Asad, R.; Andrew, K. Pattern of pathogens and their sensitivity isolated from surgical site infections at the Aga Khan University Hospital, Nairobi, Kenya. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2013, 23, 141–149. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, N.B.; Charles, C.R.; Naidoo, N.; Nokubonga, A.; Mkhwanazi, N.A.; Moustache, H.M.T.E. Infection prevention and control measures in audiology practice within public healthcare facilities in KwaZulu–Natal province, South Africa. S. Afr. J. Commun. Disord. 2019, 66, e1–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afeke, I.; Amegan–Aho, K.H.; Adu–Amankwaah, J.; Orish, V.N.; Mensah, G.L.; Mbroh, H.K.; Jamfaru, I.; Hamid, A.W.M.; Mac Ankrah, L.; Korbuvi, J. Antimicrobial profile of coagulase–negative staphylococcus isolates from categories of individuals at a neonatal intensive care unit of a tertiary hospital, Ghana. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2023, 44, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benammar, S.; Pantel, A.; Aujoulat, F.; Benmehidi, M.; Courcol, R.; Lavigne, J.P.; Romano–Bertrand, S.; Marchandin, H. First molecular characterization of related cases of healthcare–associated infections involving multidrug–resistant Enterococcus faecium vanA in Algeria. Infect. Drug Resist. 2018, 11, 1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palle, J.N.; Bassah, N.; Kamga, H.L.F.; Nkwelang, G.; Akoachere, J.F.; Mbianda, E.; Nwarie, U.G.; Njunda, A.L.; Assob, N.J.C.; Ekane, G.H. Current antibiotic susceptibility profile of the bacteria associated with surgical wound infections in the buea health district in Cameroon. Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 2014, 15, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godebo, G.; Kibru, G.; Tassew, H. Multidrug–resistant bacterial isolates in infected wounds at Jimma University Specialized Hospital, Ethiopia. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2013, 12, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogwang, M.; Paramatti, D.; Molteni, T.; Ochola, E.; Okello, T.R.; Salgado, J.O.; Kayanja, A.; Greco, C.; Kizza, D.; Gondoni, E. Prevalence of hospital–associated infections can be decreased effectively in developing countries. J. Hosp. Infect. 2013, 84, 138–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heysell, S.K.; Shenoi, S.V.; Catterick, K.; Thomas, T.A.; Friedland, G. Prevalence of methicillin–resistant Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage among hospitalised patients with tuberculosis in rural Kwazulu–Natal. S. Afr. Med. J. 2011, 101, 332–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hien, H.; Drabo, K.M.; Ouédraogo, L.; Konfé, S.; Zeba, S.; Sangaré, L.; Compaoré, S.C.; Ouédraogo, J.B.; Ouendo, E.M.; Makoutodé, M.; et al. Healthcare–associated infection in Burkina Faso: An assessment in a district hospital. J. Public Health 2012, 3, e29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakoune, E.; Lampaert, E.; Ndjapou, S.G.; Janssens, C.; Zuniga, I.; Van Herp, M.; Fongbia, J.P.; Koyazegbe, T.D.; Selekon, B.; Komoyo, G.F.; et al. A Nosocomial Outbreak of Human Monkeypox in the Central African Republic. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017, 4, ofx168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherbaum, M.; Kösters, K.; Mürbeth, R.E.; Ngoa, U.A.; Kremsner, P.G.; Lell, B.; Alabi, A. Incidence, pathogens and resistance patterns of nosocomial infections at a rural hospital in Gabon. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esebelahie, N.O.; Newton–Esebelahie, F.O.; Omoregie, R. Aerobic bacterial isolates from infected wounds. Afr. J. Clin. Exp. Microbiol. 2013, 14, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaiyuwu, O. Occurrence of bacteraemia following oral and maxillofacial surgical procedures in Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Afr. Health Sci. 2021, 21, 1692–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olu–Taiwo, M.A.; Opintan, J.A.; Codjoe, F.S.; Obeng Forson, A. Metallo–Beta–Lactamase–Producing Acinetobacter spp. from Clinical Isolates at a Tertiary Care Hospital in Ghana. Biomed. Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 3852419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdoulaye, O.; Amadou, M.L.H.; Amadou, O.; Adakal, O.; Larwanou, H.M.; Boubou, L.; Oumarou, D.; Abdoulaye, M.; Mamadou, S. Aspects épidémiologiques et bactériologiques des infections du site opératoire (ISO) dans les services de chirurgie à l’Hôpital National de Niamey (HNN). Pan Afr. Med. J. 2018, 31, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roubi, I.; Ghemri, S. Enquête sur la Prévalence des Infections Associées Aux Soins (IAS) Dans Les Établissements de Santé. Université Mohamed Khider de Biskra. 2024. Available online: http://archives.univ–biskra.dz/bitstream/123456789/30034/1/Im%C3%A9ne_ROUBI_Selma_GHEMRI.pdf (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Joshua, I.A.; Giwa, F.J.; Kwaga, J.K.P.; Kabir, J.; Owolodun, O.A.; Umaru, G.A.; Habib, A.G. Molecular Characterisation of Staphyloccocus aureus isolated from Patients in Healthcare facilities in Zaria Metropolis, Kaduna State, Nigeria. J. Epidemiol. Soc. Niger. 2021, 4, 87–101. [Google Scholar]

- Bojang, A.; Chung, M.; Camara, B.; Jagne, I.; Guérillot, R.; Ndure, E.; Howden, B.P.; Roca, A.; Ghedin, E. Genomic approach to determine sources of neonatal Staphylococcus aureus infection from carriage in the Gambia. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahoyo, T.A.; Martin–Odoom, A.; Bankolé, H.S.; Baba–Moussa, L.; Zonon, N.; Loko, F.; Prevost, G.; Sanni, A.; Dramane, K. Epidemiology and prevention of nosocomial pneumonia associated with Panton–Valentine Leukocidin (PVL) producing Staphylococcus aureus in Departmental Hospital Centre of Zou Collines in Benin. Ghana Med. J. 2012, 46, 234. [Google Scholar]

- Ouedraogo, A.S.; Some, D.A.; Dakouré, P.W.H.; Sanon, B.G.; Poda, G.E.A.; Kambou, T. Profil bactériologique des infections du site opératoire au centre hospitalier universitaire Souro Sanou de Bobo Dioulasso. Med. Trop. 2011, 71, 49–52. [Google Scholar]

- Ikumapayi, U.N.; Kanteh, A.; Manneh, J.; Lamin, M.; Mackenzie, G.A. An outbreak of Serratia liquefaciens at a rural health center in The Gambia. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2016, 10, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabiri, S.; Yenli, E.; Kyere, M.; Anyomih, T.T.K. Surgical Site Infections in Emergency Abdominal Surgery at Tamale Teaching Hospital, Ghana. World J. Surg. 2018, 42, 916–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mafikoya, B.O.; Niemogha, M.T.; Ogunsola, F.T.; Atoyebi, O.A. Predictors of surgical site infections of the abdomen in Lagos, Nigeria. Niger. Q. J. Hosp. Med. 2021, 21, 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Labi, A.K.; Obeng–Nkrumah, N.; Owusu, E.; Bjerrum, S.; Bediako–Bowan, A.; Sunkwa–Mills, G.; Akufo, C.; Fenny, A.P.; Opintan, J.A.; Enweronu–Laryea, C. Multi–centre point–prevalence survey of hospital–acquired infections in Ghana. J. Hosp. Infect. 2019, 101, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ezenwa, B.N.; Oladele, R.O.; Akintan, P.E.; Fajolu, I.B.; Oshun, P.O.; Oduyebo, O.O.; Ezeaka, V.C. Invasive candidiasis in a neonatal intensive care unit in Lagos, Nigeria. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2017, 24, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anago, E.; Ayi–Fanou, L.; Akpovi, C.D.; Hounkpe, W.B.; Agassounon–Djikpo Tchibozo, M.; Bankole, H.S.; Sanni, A. Antibiotic resistance and genotype of beta–lactamase producing Escherichia coli in nosocomial infections in Cotonou, Benin. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2015, 14, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyepong, N.; Govinden, U.; Owusu–Ofori, A.; Allam, M.; Ismail, A.; Pedersen, T.; Sundsfjord, A.; Arnfinn, S.; Maresca, J.A. Whole–Genome Sequences of Two Multidrug–Resistant Acinetobacter baumannii Strains Isolated from Patients with Urinary Tract Infection in Ghana. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2019, 8, e00270-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duedu, K.O.; Offei, G.; Codjoe, F.S.; Donkor, E.S. Multidrug Resistant Enteric Bacterial Pathogens in a Psychiatric Hospital in Ghana: Implications for Control of Nosocomial Infections. Int. J. Microbiol. 2017, 2017, 9509087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labi, A.K.; Bjerrum, S.; Enweronu–Laryea, C.C.; Ayibor, P.K.; Nielsen, K.L.; Marvig, R.L.; Newman, M.J.; Andersen, L.P.; Kurtzhals, J.A. High Carriage Rates of Multidrug–Resistant Gram–Negative Bacteria in Neonatal Intensive Care Units From Ghana. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2020, 7, ofaa109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulibaly, Y.; Amadou, I.; Koné, O.; Coulibaly, O.M.; Diop, T.H.M.; Doumbia, A.; Kamaté, B.; Djiré, M.K.; Traoré, A.; Ouologuem, H. Infections associées aux soins en chirurgie pédiatrique au CHU Gabriel Touré, Bamako, Mali. Mali. Méd. 2020, 35, 15–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Aye, E.C.; Omoregie, R.; Ohiorenuan, I.I.; Onemu, S. Microbiology of Wound Infections and Its Associated Risk Factors Among Patients of a Tertiary Hospital in Benin City, Nigeria. 2011. Available online: https://www.sid.ir/EN/VEWSSID/J_pdf/129720110207.pdf (accessed on 18 May 2025).

- Amissah, N.A.; Buultjens, A.H.; Ablordey, A.; van Dam, L.; Opoku–Ware, A.; Baines, S.L.; Bulach, D.; Tetteh, C.S.; Prah, I.; van der Werf, T.S. Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Transmission in a Ghanaian Burn Unit: The Importance of Active Surveillance in Resource–Limited Settings. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ka, R. Aspects bactériologiques des infections liées aux cathéters veineux à l’hôpital Dalal Jamm de Guédiawaye (Sénégal). Rev. Mali. Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 19, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diarra, A.; Keita, K.; Tounkara, I.; Traoré, A.; Koné, A.; Konaté, M.; Karembé, B.; Keita, M.A.; Traoré, I.; Togola, M. Infections du site operatoire en chirurgie generale du centre hospitalier universitaire bocar sidy sall de kati. Mali. Med. 2020, 35, 20. [Google Scholar]

- Afle, F.C.D.; Quenum, K.J.; Hessou, S.; Johnson, R.C. Etat des lieux des infections associées aux soins dans deux hôpitaux publics du sud Benin (Afrique de l’ouest): Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Zone d’Abomey–Calavi/Sô–Ava et Centre Hospitalier de Zone de Cotonou 5. J. Appl. Biosci. 2018, 121, 12192–12201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dia, N.M.; Cissoko, Y.; Diouf, A.; Seydi, M. Results of a survey incidence of the cases of nosocomial infections with multidrug resistant bacteria in a hospital center in Dakar (Senegal). Rev. Mali. D Infect. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Ahoyo, T.A.; Bankolé, H.S.; Adéoti, F.M.; Gbohoun, A.A.; Assavèdo, S.; Amoussou–Guénou, M.; Kindé–Gazard, D.A.; Pittet, D. Prevalence of nosocomial infections and anti–infective therapy in Benin: Results of the first nationwide survey in 2012. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2014, 3, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukuke, H.M.; Kasamba, E.; Mahuridi, A.; Ngatu, N.R.; Narufumi, S.; Mukengeshayi, A.N.; Malou, V.; Makoutode, M.; Kaj, F.M. L’incidence des infections nosocomiales urinaires et des sites opératoires dans la maternité de l’Hôpital Général de Référence de Katuba à Lubumbashi en République Démocratique du Congo. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2017, 28, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowman, W. Active surveillance of hospital–acquired infections in South Africa: Implementation, impact and challenges. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016, 106, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliyasu, G.; Dayyab, F.M.; Abubakar, S.; Inuwa, S.; Tambuwal, S.H.; Tiamiyu, A.B.; Habib, Z.G.; Gadanya, M.A.; Sheshe, A.A.; Mijinyawa, M.S. Laboratory–confirmed hospital–acquired infections: An analysis of a hospital’s surveillance data in Nigeria. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gezmu, A.M.; Bulabula, A.N.H.; Dramowski, A.; Bekker, A.; Aucamp, M.; Souda, S.; Nakstad, B. Laboratory–confirmed bloodstream infections in two large neonatal units in sub–Saharan Africa. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 103, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dramowski, A.; Whitelaw, A.; Cotton, M.F. Burden, spectrum, and impact of healthcare–associated infection at a South African children’s hospital. J. Hosp. Infect. 2016, 94, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dan–Nwafor, C.C.; Ipadeola, O.; Smout, E.; Ilori, E.; Adeyemo, A.; Umeokonkwo, C.; Nwidi, D.; Nwachukwu, W.; Ukponu, W.; Omabe, E.; et al. A cluster of nosocomial Lassa fever cases in a tertiary health facility in Nigeria: Description and lessons learned, 2018. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2019, 83, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dramowski, A.; Cotton, M.F.; Whitelaw, A. Surveillance of healthcare–associated infection in hospitalised South African children: Which method performs best? S. Afr. Med. J. 2016, 107, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.; Ehlers, M.M.; Ismail, F.; Peirano, G.; Becker, P.J.; Pitout, J.D.D.; Kock, M.M. Acinetobacter baumannii: Epidemiological and Beta–Lactamase Data From Two Tertiary Academic Hospitals in Tshwane, South Africa. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivier, C.; Kunneke, H.; O’Connell, N.; Von Delft, E.; Wates, M.; Dramowski, A. Healthcare–associated infections in paediatric and neonatal wards: A point prevalence survey at four South African hospitals. S. Afr. Med. J. 2018, 108, 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spicer, K.B.; Green, J.; Dhada, B. Hospital–acquired infections in paediatric medical wards at a tertiary hospital in KwaZulu–Natal, South Africa. Paediatr. Int. Child. Health 2018, 38, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakupa, D.K.; Muenze, P.K.; Byl, B.; Wilmet, M.D. Study of the prevalence of nosocomial infections and associated factors in the two university hospitals of Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 24, 275. [Google Scholar]

- Tagoe, D.N.A.; Baidoo, S.E.; Dadzie, I.; Tengey, D.; Agede, C. Potential sources of transmission of hospital acquired infections in the volta regional hospital in Ghana. Ghana Med. J. Mars 2011, 45, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, D.; Magombe, I. Hospital acquired infections in a large north Ugandan hospital. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2011, 52, 55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Makanjuola, O.B.; Fayemiwo, S.A.; Okesola, A.O.; Gbaja, A.; Ogunleye, V.A.; Kehinde, A.O.; Bakare, R.A. Pattern of multidrug resistant bacteria associated with intensive care unit infections in Ibadan, Nigeria. Ann. Ib. Postgrad. Med. 2018, 16, 162–169. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Okello, T.R.; Kansiime, J.; Odora, J. Invasive procedures and Hospital Acquired Infection (HAI) in A large hospital in Northern Uganda. East Cent. Afr. J. Surg. 2014, 19, 77–84. [Google Scholar]

- Rafaï, C.; Frank, T.; Manirakiza, A.; Gaudeuille, A.; Mbecko, J.R.; Nghario, L.; Serdouma, E.; Tekpa, B.; Garin, B.; Breurec, S. Dissemination of IncF–type plasmids in multiresistant CTX–M–15–producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates from surgical–site infections in Bangui, Central African Republic. BMC Microbiol. 2015, 15, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okolo, M.O.; Toma, B.O.; Onyedibe, K.I.; Emanghe, U.; Banwat, E.B.; Egah, D.Z. Bacterial Contamination In A Special Care Baby Unit Of A Tertiary Hospital In Jos, Nigeria. Niger. J. Med. 2016, 25, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beye, S.A.; Maiga, A.; Cissoko, Y.; Guindo, I.; Dicko, O.A.; Maiga, M.; Abeghe, A.T.A.; Diakité, M.; Diallo, B.; Dao, S. Prevalence of nosocomial infections at the Centre Hospitalier Universitaire du Point, G. in Bamako, Mali. Rev. Mali. D Infect. Microbiol. 2024, 19, 45. [Google Scholar]

- Seni, J.; Najjuka, C.F.; Kateete, D.P.; Makobore, P.; Joloba, M.L.; Kajumbula, H.; Kapesa, A.; Bwanga, F. Antimicrobial resistance in hospitalized surgical patients: A silently emerging public health concern in Uganda. BMC Res. Notes 2013, 6, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembélé, G. Infection du Site Opératoire dans le Service de Traumatologie à L’hôpital de Sikasso. Ph.D. Thesis, USTTB, Bamako, Mali, 2020. Available online: https://library.adhl.africa/handle/123456789/14015 (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Saidoun, A.A. Surveillance des Infections Nosocomiales en Pédiatrie au CHU Béni Messous d’Alger. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculté de Médecine d’Alger, El Biar, Algeria, 2021. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel–03374867/ (accessed on 13 October 2025).

- Rim, L. Facteurs Prédictifs des Infections Nosocomiales en Milieu de Réanimation 2016. Available online: https://toubkal.imist.ma/handle/123456789/28014 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Angoue, T.A.A. Prévalence des Infections Nosocomiales Dans 10 Services du CHU du Point G. Ph.D. Thesis, Thèse de Médecine USTTB, Bamako, Mali, 2020. Available online: https://bibliosante.ml/bitstream/handle/123456789/4442/20M05.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Mulu, W.; Kibru, G.; Beyene, G.; Damtie, M. Postoperative nosocomial infections and antimicrobial resistance pattern of bacteria isolates among patients admitted at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahirdar, Ethiopia. Ethiop. J. Health Sci. 2012, 22, 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Mwita, J.C.; Souda, S.; Magafu, M.G.M.D.; Massele, A.; Godman, B.; Mwandri, M. Prophylactic antibiotics to prevent surgical site infections in Botswana: Findings and implications. Hosp. Pract. 2018, 46, 97–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaat, M.; Zayed, B.; Tolba, S.; Abdou, E.; Gomaa, M.; Itani, D.; Hutin, Y.; Hajjeh, R. Increasing antimicrobial resistance in world health organization eastern mediterranean region, 2017–2019. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2022, 28, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Togo, A.; Samaké, M.; Sarro, Y.S.; Youssouf, D.; Kanikomo, D.; Diop, M.; Yacaria, C.; Niani, M.; Mamadou, C.; Diarra, B. Healthcare–associated infection in surgery department: A big challenge for African surgical teams. J. West Afr. Coll. Surg. 2023, 13, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, C.T.; Langendorf, C.; Garba, S.; Sayinzonga–Makombe, N.; Mambula, C.; Mouniaman, I.; Hanson, K.E.; Grais, R.F.; Isanaka, S. Risk of community–and hospital–acquired bacteremia and profile of antibiotic resistance in children hospitalized with severe acute malnutrition in Niger. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 119, 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, A.M.; Mthanti, M.A.; Haumann, C.; Tyalisi, N.; Boon, G.P.G.; Sooka, A.; Keddy, K.H. Nosocomial Outbreak of Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Primarily Affecting a Pediatric Ward in South Africa in 2012. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 627–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Schalkwyk, E.; Iyaloo, S.; Naicker, S.D.; Maphanga, T.G.; Mpembe, R.S.; Zulu, T.G.; Mhlanga, M.; Mahlangu, S.; Maloba, M.B.; Ntlemo, G.; et al. Large Outbreaks of Fungal and Bacterial Bloodstream Infections in a Neonatal Unit, South Africa, 2012–2016. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 1204–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasme–Guillao, E.; Amon–Tanoh–Dick, F.; GBonon, V.; Akaffou, E.A.; Kabas, R.; Faye–Kette, H. Infections a Klebsiella pneumonia et Enterobacter cloacae en néonatologie a Abidjan. J. Pédiatrie Puéricult. 2011, 24, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nouetchognou, J.S.; Ateudjieu, J.; Jemea, B.; Mesumbe, E.N.; Mbanya, D. Surveillance of nosocomial infections in the Yaounde University Teaching Hospital, Cameroon. BMC Res. Notes 2016, 9, 505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoh, S.; Yi, L.; Sevalie, S.; Guo, X.; Adekanmbi, O.; Smalle, I.O.; Williams, N.; Barrie, U.; Koroma, C.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Incidence and risk factors of surgical site infections and related antibiotic resistance in Freetown, Sierra Leone: A prospective cohort study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoh, S.; Yi, L.; Russell, J.B.W.; Zhang, J.; Sevalie, S.; Zhao, Y.; Kanu, J.S.; Liu, P.; Conteh, S.K.; Williams, C.E.E.; et al. High incidence of catheter–associated urinary tract infections and related antibiotic resistance in two hospitals of different geographic regions of Sierra Leone: A prospective cohort study. BMC Res. Notes 2023, 16, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category | Label | Information to Be Collected |

|---|---|---|

| General information | Item ID | Awarded by team |

| Authors | Authors’ names | |

| Year of publication | Year of publication of the study | |

| Title | Article Title | |

| DOI/PMID/Link | Study ID | |

| Study characteristics | Type of study | Case–control, Descriptive cohort, Before–after study; Case report; Case series Cross–sectional study |

| Objectives of the study | Describe the objective of the study | |

| WHO Region | Region of the world defined by the WHO | |

| Country | Countries where the study was conducted | |

| Study period | Duration of the study | |

| Population details | Population or subject studied | General population, children, elderly, etc. |

| Sources of infection | Acquired in hospital | |

| Population information | Gender, age, health status, inpatient/outpatient service, etc. | |

| Exhibition details | Mode of transmission | Individual cases of illness, epidemics, etc. |

| HAIs source | Patients, staff; equipment | |

| Type of samples | Pus swab, urine, blood, catheters, sputum, nasopharyngeal aspirate, expectorations, and hospital consumables, environmental swab | |

| Number of samples | Number | |

| Laboratory methods | Pathogens identified | Genera and species |

| Type of pathogens | Bacteria, fungi, viruses | |

| Laboratory identification method | Genomic, genotypic, unspecified, phenotypic | |

| Antibiogram | Antibiotics tested | |

| AST Guidelines | CLSI; EUCAST–CASFM | |

| Resistance profile | ESBL, CRAB; CRE; MRSA | |

| Main findings and results | Main results | Key findings of the article |

| Main conclusions | Conclusions drawn by the authors | |

| Additional notes | Any other relevant information |

| Criteria | Source of Bias | Applied Scale |

|---|---|---|

| Study using data from one’s own work or another source | Data source | 1—External; 2—Mixed; 3—Internal |

| Data used clearly indicated (with source if necessary) | Data availability | 1—No; 2—Unclear; 3—Yes |

| Estimate or measure the size of the exposed population | Size of exposed population | 1—Unclear; 2—Estimated; 3—Measured |

| Estimation or measurement of the size of the sick population | Size of the sick population | 1—Unclear; 2—Estimated; 3—Measured |

| Characteristics of individuals clearly presented | Population health status | 1—Not described; 2—Described |

| Assessment of population size with critical evaluation by the author | Population size | 1—No; 2—Yes |

| Assessment of the author’s intervention method | Type of study | 1—Not described; 2—Described |

| Appreciate the different sources of HAIs | HAIs Sources | 1—Not described; 2—Described |

| Clearly identified HAIs source | HAIs Sources | 1—No; 2—Unclear; 3—Yes |

| Critical evaluation by the authors of the study results and comparison with other studies | Discussion of results | 1—No critical evaluation by the authors; 2—Critical evaluation by the authors |

| Critical assessment by the authors of factors that may influence their results | Discussion of factors influencing the results | 1—No critical evaluation by the authors; 2—Critical evaluation by the authors |

| Band | Methodological Quality | Score (%) |

|---|---|---|

| I | Forte | (28–33) 75–100 |

| II | Moderate | (17–27) 50–75 |

| III | Weak | (<16) <50 |

| Source Category | Origin of the Microorganism | Specific Sources | Mode of Transmission Predominant |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Endogenous Source (Self–contamination) | The patient himself | Patient flora (digestive, cutaneous, respiratory) which enters through an artificial or natural entry point. | Migration/Direct inoculation (during an invasive or surgical procedure): the patient’s germs are introduced into a sterile site (e.g., catheter, surgical site). |

| 2. Exogenous Source (Cross–Contamination) | External to the patient | ||

| Humans: Other Patients | Infected patients or asymptomatic carriers (especially MDR). | Direct or indirect contact (through the hands of staff or shared equipment). | |

| Humans: Healthcare Staff | Asymptomatic carrier staff members. Lack of hygiene (hands, clothing). | Handling (hands not disinfected between patients) or airborne (in case of unmasked respiratory infection). | |

| Environmental/Material: Equipment and Devices | Invasive devices (catheters, probes, ventilators, etc.). Improperly sterilized surgical instruments. Shared surfaces (bed, table, handles) and objects. | Direct inoculation (via the device) or indirect contact (via surfaces/materials). | |

| Environmental/Material: Inanimate Environment | Water (taps, showers, air conditioning systems). Air (works, ventilation). Food (very rare). | Airborne (inhalation) or waterborne (ingestion, nebulization). |

| Type of Study | Bibliographic References | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Case–control | [33,34] | 2 (2.1) |

| Cohort | [35,36] | 10 (10.4) |

| Before–and–after study | [37] | 1 (1.1) |

| Case report | [38,39,40] | 3 (3.2) |

| Case series | [41] | 1 (1.1) |

| Transversal | [42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,119] | 78 (82.1) |

| Total | 95 |

| Case–Control | Descriptive Cohort | Before-and-After Study | Cross-Sectional Study | Case Report | Case Series | Total n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years | |||||||

| 2011–2015 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 29 | 2 | 0 | 36 (37.9) |

| 2016–2020 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 39 | 1 | 1 | 44 (46.3) |

| 2021–2024 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 15 (15.8) |

| African regions | |||||||

| West Africa | 0 | 7 | 1 | 45 | 3 | 1 | 57 (60.0) |

| Central Africa | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 8 (8.4) |

| East Africa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 9 (9.5) |

| South Africa | 2 | 2 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 16 (16.8) |

| North Africa | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5 (5.3) |

| Total | 2 | 10 | 1 | 78 | 3 | 1 | 95 |

| Type of HAIs Sources | Bibliographic References | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Endogenous | [44,47,50,57,71,79,90,113] | 8 (8.4) |

| Exogenous | [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,45,46,48,49,52,53,55,56,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,67,68,69,70,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,80,83,84,86,87,88,89,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112,116,117,118,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127] | 79 (83.2) |

| Exogenous and Endogenous | [54,66,81,82,85,99,114,115] | 8 (8.4) |

| Total | 95 |

| Methodological Quality | Bibliographic References | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| High (>75%) | [33,34,35,36,37,40,41,42,43,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,57,58,59,60,61,63,64,65,66,67,69,71,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,86,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,106,107,108,109,111,112,113,114,115,116,117,118,120,121,122,123,124,125,126,127] | 81 (85.2) |

| Moderate (50–75%) | [38,39,44,56,62,68,70,73,74,83,87,105,110] | 13 (13.7) |

| Acceptable (<50%) | [72] | 1 (1.1) |

| Type of Study | Scope | Country | Bibliographic Reference | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case–control n = 2 (2.1) | Local n = 2 (2.1) | South Africa | [34,35] | 2 (2.1) |

| Descriptive cohort n = 10 (10.5) | Local n = 10 (10.5) | South Africa | [120,122] | 2 (2.1) |

| Cameroon | [126] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Ivory Coast | [125] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Ghana | [123] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Mali | [121] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Niger | [124] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Sierra Leone | [36,37,127] | 3 (3.2) | ||

| Before–after study n = 1 (1.1) | Local n = 1 (1.1) | Senegal | [33] | 1 (1.1) |

| Cross–sectional study n = 78 (82.1) | Local n = 75 (78.9) | South Africa | [26,51,58,64,94,97,99,100,102] | 9 (9.5) |

| Algeria | [48,60,72,113] | 4 (4.2) | ||

| Benin | [45,75,82,90] | 4 (4.2) | ||

| Botswana | [117] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Botswana and South Africa | [96] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Burkina Faso | [52,65,76] | 3 (3.2) | ||

| Cameroon | [54,61] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Ethiopia | [62,117] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Gabon | [67] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Gambia | [74,77] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Ghana | [47,59,70,78,83,84,85,87,104] | 9 (9.5) | ||

| Kenya | [57] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Mali | [86,89,110,112,115] | 5 (5.3) | ||

| Morocco | [115] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Niger | [71] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Nigeria | [42,44,46,50,53,55,68,69,73,79,81,87,95,98,106,109] | 16 (16.8) | ||

| Uganda | [63,105,107,111] | 4 (4.2) | ||

| Central African Republic | [66,109] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) | [93,103] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Rwanda | [49] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Senegal | [88,91] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Sierra Leone | [43] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Tanzania | [56] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| National n = 3 (3.2) | South Africa | [101] | 1 (1.1) | |

| Benin | [92] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Ghana | [80] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Case report n = 3 (3.2) | Local n = 3 (3.2) | Mali | [38] | 1 (1.1) |

| Senegal | [39,40] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Case series n = 1 (1.1) | Local n = 1 (1.1) | Gambia | [41] | 1 (1.1) |

| Total | 95 (100.0) |

| Scope n (%) | Investigation Methods n (%) | Country | Bibliographic Reference | n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local n = 92 (96.8) | Clinical n = 5 (5.3) | South Africa | [58] | 1 (1.1) |

| Ghana | [78] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Uganda | [63,105] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Sierra Leone | [37] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Genomics n = 2 | Gambia | [74] | 1 (1.1) | |

| Ghana | [87] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Genotypic n = 2 | Nigeria | [98] | 1 (1.1) | |

| Central African Republic | [66] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Phenotypic n = 67 (70.5) | South Africa | [26,35,51,64,94,97,99,102,122] | 9 (9.5) | |

| Algeria | [48,72,113] | 3 (3.2) | ||

| Benin | [45,90] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Botswana | [117] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Botswana and South Africa | [96] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Burkina Faso | [52,65,76] | 3 (3.2) | ||

| Cameroon | [54,61,126] | 3 (3.2) | ||

| Ivory Coast | [125] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Ethiopia | [62,117] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Gabon | [67] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Gambia | [41,77] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Ghana | [84,104] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Kenya | [57] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Mali | [38,86,89,110,112,116,121] | 7 (7.4) | ||

| Morocco | [115] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Niger | [71,124] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Nigeria | [42,44,50,53,55,68,69,79,81,86,95,106,109] | 13 (13.7) | ||

| Uganda | [107,112] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Central African Republic | [108] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) | [93,103] | 2(2.1) | ||

| Rwanda | [49] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Senegal | [33,88,91] | 3 (3.2) | ||

| Sierra Leone | [36,43,127] | 3 (3.2) | ||

| Tanzania | [56] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Phenotypic + genotypic n = 16 (16.8) | South Africa | [34,100,120] | 3 (3.2) | |

| Algeria | [60] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Benin | [75,82] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Ghana | [47,59,70,83,85,123] | 6 (6.3) | ||

| Nigeria | [46,73] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| Senegal | [39,40] | 2 (2.1) | ||

| National n = 3 (3.2) | Phenotypic n = 3 (3.2) | South Africa | [101] | 1 (1.1) |

| Benin | [92] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Ghana | [80] | 1 (1.1) | ||

| Total | 95 |

| Name of the Pathogen | Bibliographic References | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacteria n = 48 | (50.5) | |

| Acinetobacter baumannii | [26,33,35,43,45,48,51,56,83,86,90,91,92,93,96,100,106,114,116,123,124] | 21 (22.1) |

| Acinetobacter spp. | [67,70,79,85,90,91,112,116,126] | 9 (9.5) |

| Alcaligenes | [69] | 1 (1.1) |

| Bacillus spp. | [104] | 1 (1.1) |

| Gram–negative bacteria | [53,88,110,114,121,127] | 6 (6.3) |

| Gram–positive bacteria | [53,88,127] | 3 (3.2) |

| Bacteroides spp. | [69,79] | 2 (2.1) |

| Bacteroides fragile | [42] | 1 (1.1) |

| Citrobacter spp. | [62,85,92,106,126] | 5 (5.3) |

| Citrobacter friends | [93] | 1 (1.1) |

| Clostridium spp. | [69] | 1 (1.1) |

| Coagulase–negative Staphylococcus | [91,92,117] | 3 (3.2) |

| Corynebacterium aurimucosum | [39] | 1 (1.1) |

| Enterobacter spp. | [61,62,67,85,106,116,126] | 7 (7.4) |

| Enterobacter cloacae | [33,34,45,51,54,61,86,116,125] | 9 (9.5) |

| Enterobacter faecalis | [86] | 1 (1.1) |

| Enterococcus faecalis | [43,56,93,94,124] | 4 (4.2) |

| Enterococcus faecium van A | [60] | 1 (1.1) |

| Enterococcus spp. | [36,67,68,92] | 4 (4.2) |

| Escherichia coli | [36,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,52,54,55,56,57,59,61,65,67,68,71,76,80,82,84,85,86,89,90,92,93,95,101,103,104,106,111,112,116,122,123,124,126] | 41 (43.2) |

| Hafnia alvei | [46,106] | 2 (2.1) |

| Klebsiella oxytoca | [36,46] | 2 (2.1) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | [33,34,36,42,43,45,48,49,51,54,56,57,61,65,67,68,71,72,84,86,89,90,95,96,97,99,106,112,116,123,124,125] | 31 (32.6) |

| Klebsiella spp. | [53,58,62,63,81,85,86,88,91,97,108,111,113,114,127] | 15 (15.8) |

| Listeria monocytogenes | [96] | 1 (1.1) |

| Morganella | [84] | 1 (1.1) |

| Peptococcus spp. | [42] | 1 (1.1) |

| Proteus mirabilis | [36,42,46,54,56,61,86,106,113] | 9 (9.5) |

| Proteus spp. | [55,62,68,79,87,95,106] | 7 (7.4) |

| Proteus vulgaris | [126] | 1 (1.1) |

| Providencia spp. | [62,69] | 2 (2.1) |

| Providencia stuartii | [56] | 1 (1.1) |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [36,42,43,44,45,46,48,51,54,56,57,61,62,68,71,76,79,80,84,85,86,89,90,91,92,93,95,102,103,104,106,112,113,115,116,123] | 35 (36.8) |

| Pseudomonas spp. | [102,111,126] | 3 (3.2) |

| Salmonella arizonae | [126] | 1 (1.1) |

| Salmonella enterica | [40,120] | 2 (2.1) |

| Non–typhoidal Salmonella | [124] | 1 (1.1) |

| Salmonella spp. | [92,103] | 2 (2.1) |

| Salmonella typhi | [103] | 1 (1.1) |

| Serratia liquefaciens | [77] | 1 (1.1) |

| Serratia marcescens | [34,61] | 2 (2.1) |

| Shigella spp. | [103] | 1 (1.1) |

| Staphylococcus aureus | [33,36,42,43,44,45,48,49,51,52,54,55,56,57,59,61,62,64,67,68,69,71,72,73,74,75,76,80,86,87,89,90,91,92,93,95,96,97,99,101,102,103,104,106,111,112,115,117,123] | 51 (53.7) |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | [59] | 1 (1.1) |

| Staphylococcus spp. | [52,56] | 2 (2.1) |

| Group B Streptococcus | [96,101] | 2 (2.1) |

| Streptococcus spp. | [69,91] | 2 (2.1) |

| Streptococcus viridans | [69] | 1 (1.1) |

| Fungi/mycoses n = 4 | (4.2) | |

| Candida albicans | [26,51,56,86,92,101,113,115,122] | 9 (9.5) |

| Candida krusei | [122] | 1 (1.1) |

| Candida parapsilosis | [122] | 1 (1.1) |

| Candida spp. | [42,44,52,53,81,92,97,99,113,116] | 11 (11.6) |

| Virus n = 4 | [4] | 4 (4.2) |

| Virus (HVA, HVB, HVC) | [72] | 1 (1.1) |

| Virus (RSV, Adenovirus) | [97,99] | 2 (2.1) |

| Lassa fever virus | [98] | 1 (1.1) |

| Monkeypox virus (Mpox) | [66] | 1 (1.1) |

| UNSPECIFIED n = 9 | [9] | (9.5) |

| Not specified | [37,41,50,58,63,78,94,105,107] | 9 (9.5) |

| Phenotypic Profile | Bibliographic References | Number n = 95 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| ESBL | [26,43,45,48,56,62,65,67,76,80,85,86,89,90,91,96,98,100,102,107,120,121,123,124,125,127] | 26 (27.4) |

| MRSA/Methicillin–resistant | [33,48,53,56,62,64,67,73,74,75,88,90,92,95,97,99,101,111,113,123] | 20 (21.1) |

| MDR/Multi–resistance | [53,54,56,60,61,62,70,84,100,111,117,120,126] | 13 (13.7) |

| CRE/Carbapenemases | [35,36,45,80,85,96,100,123,124,127] | 10 (10.5) |

| C3GR | [33,38,80,85,95,123] | 6 (6.3) |

| Tetracycline R | [44,59,68,84,86,87] | 6 (6.3) |

| Beta–lactamase | [44,68,89,125] | 4 (4.2) |

| Ceftazidime R | [88,92,115] | 3 (3.2) |

| Fluconazole R | [97,122] | 2 (2.1) |

| Cephalosporinase | [110] | 1 (1.1) |

| Amphotericin B (sensitive) | [122] | 1 (1.1) |

| CRAB | [26,48,100] | 3 (3.2) |

| VRE | [92,113] | 2 (2.1) |

| Partial resistance/not specified | [34,35,39,41,49,50,55,58,61,63,69,72,77,78,79,87,94,98,102,103,104,105,107,109] | 25 (26.3) |

| Name of the Pathogen | Resistance Rate (%) | Common Resistance Phenotypes | Bibliographic References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | ESBL (56–79.2) | ESBL, resistance to 3rd generation cephalosporins, multi–resistance | [36,65,82,84,111] |

| Ampicillin resistance (97.6) | |||

| Amoxicillin resistance (95.2) | |||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | ESBL (59.2–80.3) | ESBL, CRE, resistance to beta–lactams, cephalosporins | [26,38,72,85,96,124] |

| Carbapenem resistance (1.3–5.24) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | MRSA (15–100) | MRSA, oxacillin resistance, multi–drug resistance to beta–lactams | [26,48,62,64,75,87] |

| Penicillin resistance (88.6–100) | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Ciprofloxacin resistance (50–68.2) | Resistance to fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, carbapenems | [35,48,76,91,123] |

| Resistance to meropenem (31) | |||

| Acinetobacter baumannii | Multidrug resistance (MDR) (62.1–90) | CRAB, resistance to cephalosporins, carbapenems, colistin (rare) | [26,35,48,70,83,100] |

| Carbapenem resistance (47.6–75.3) | |||

| Enterobacter spp. | ESBL (58.3) | ESBL, cephalosporin resistance, variable sensitivity to carbapenems | [34,72,85,125] |

| Resistance to C3G frequent | |||

| Enterococcus spp. | Vancomycin resistance (67.5) | VRE, resistance to glycopeptides, aminopenicillins | [60,67,92] |

| Ampicillin resistance frequent | |||

| Candida spp. | Fluconazole resistance: variable | Resistance to azoles, sensitivity to amphotericin B | [81,97,122] |

| C. krusei: intrinsic resistance | |||

| Salmonella spp. | ESBL: detected | Resistance to beta–lactams, aminoglycosides, cotrimoxazole | [40,120] |

| Multi–resistance ≥ 6 antibiotics | |||

| Proteus spp. | Ampicillin resistance (100) | Resistance to beta–lactams, aminopenicillins, quinolones | |

| Multi–resistance frequent |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gahimbare, L.; Guessennd, N.K.; Muvunyi, C.M.; Fuller, W.; Coulibaly, S.O.; Cihambanya, L.; Kariyo, P.C.; Perovic, O.; Mwamelo, A.J.; Maxime, D.K.; et al. Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections in the WHO African Region: Systematic Review of Literature from 2011 to 2024. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121287

Gahimbare L, Guessennd NK, Muvunyi CM, Fuller W, Coulibaly SO, Cihambanya L, Kariyo PC, Perovic O, Mwamelo AJ, Maxime DK, et al. Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections in the WHO African Region: Systematic Review of Literature from 2011 to 2024. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121287

Chicago/Turabian StyleGahimbare, Laetitia, Nathalie K. Guessennd, Claude Mambo Muvunyi, Walter Fuller, Sheick Oumar Coulibaly, Landry Cihambanya, Pierre Claver Kariyo, Olga Perovic, Ambele Judith Mwamelo, Diané Kouao Maxime, and et al. 2025. "Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections in the WHO African Region: Systematic Review of Literature from 2011 to 2024" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121287

APA StyleGahimbare, L., Guessennd, N. K., Muvunyi, C. M., Fuller, W., Coulibaly, S. O., Cihambanya, L., Kariyo, P. C., Perovic, O., Mwamelo, A. J., Maxime, D. K., Gbonon, V., Fernique, K. K., Ndoye, B., & Ahmed, Y. A. (2025). Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections in the WHO African Region: Systematic Review of Literature from 2011 to 2024. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1287. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121287