Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli and Pediatric UTIs: A Review of the Literature and Selected Experimental Observations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Epidemiology of Pediatric Urinary Tract Infections

3. Treatment of Bacterial Urinary Tract Infections

4. Antibiotic Resistance Trends with an Emphasis on Escherichia coli

5. UTI Pathogenesis

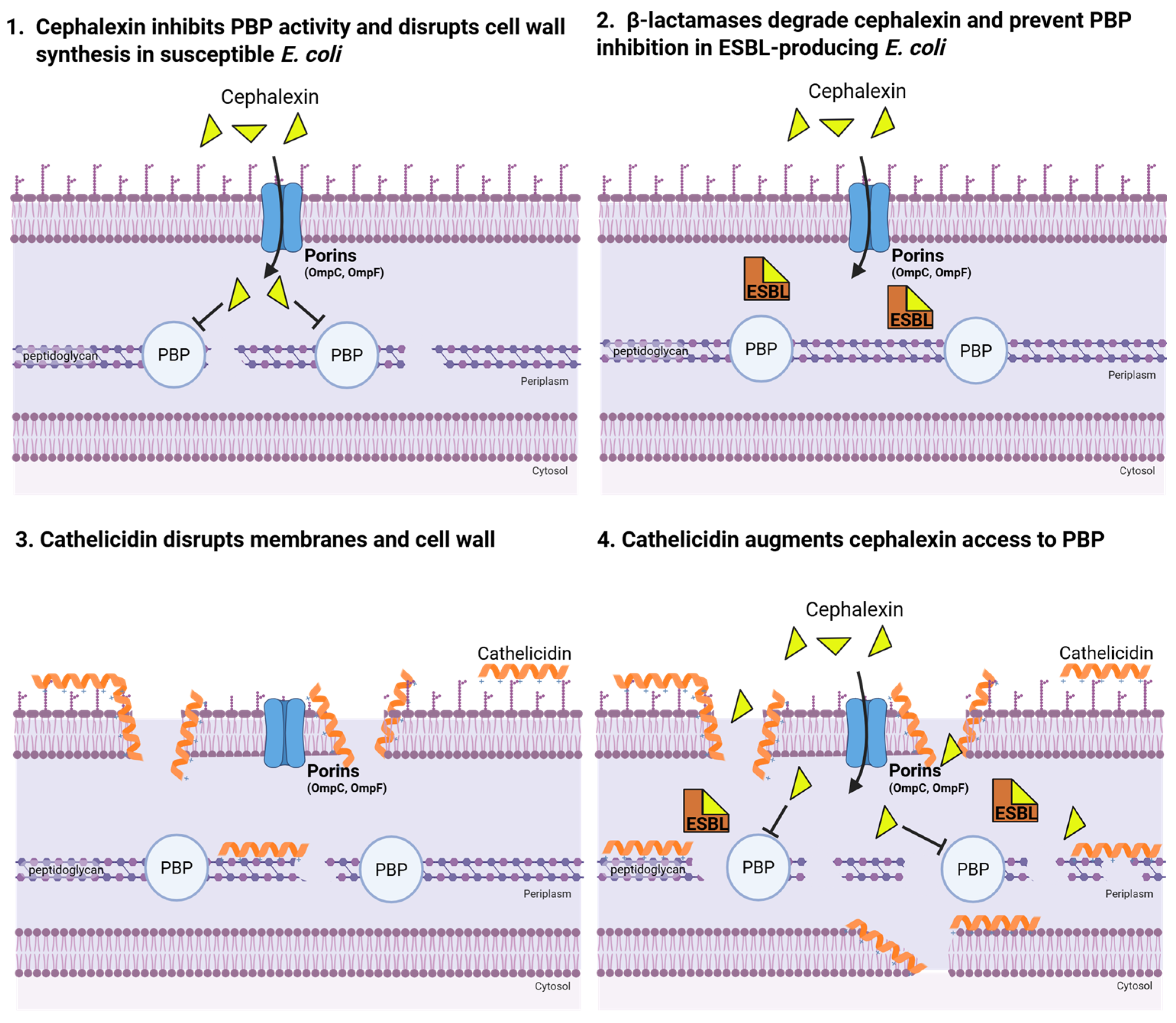

6. Cathelicidin in the Urinary Tract

7. Innate Immunity and Antibiotic Synergy

8. Selected Experimentation

8.1. Experimental Rationale and Hypothesis

8.2. Materials and Methods

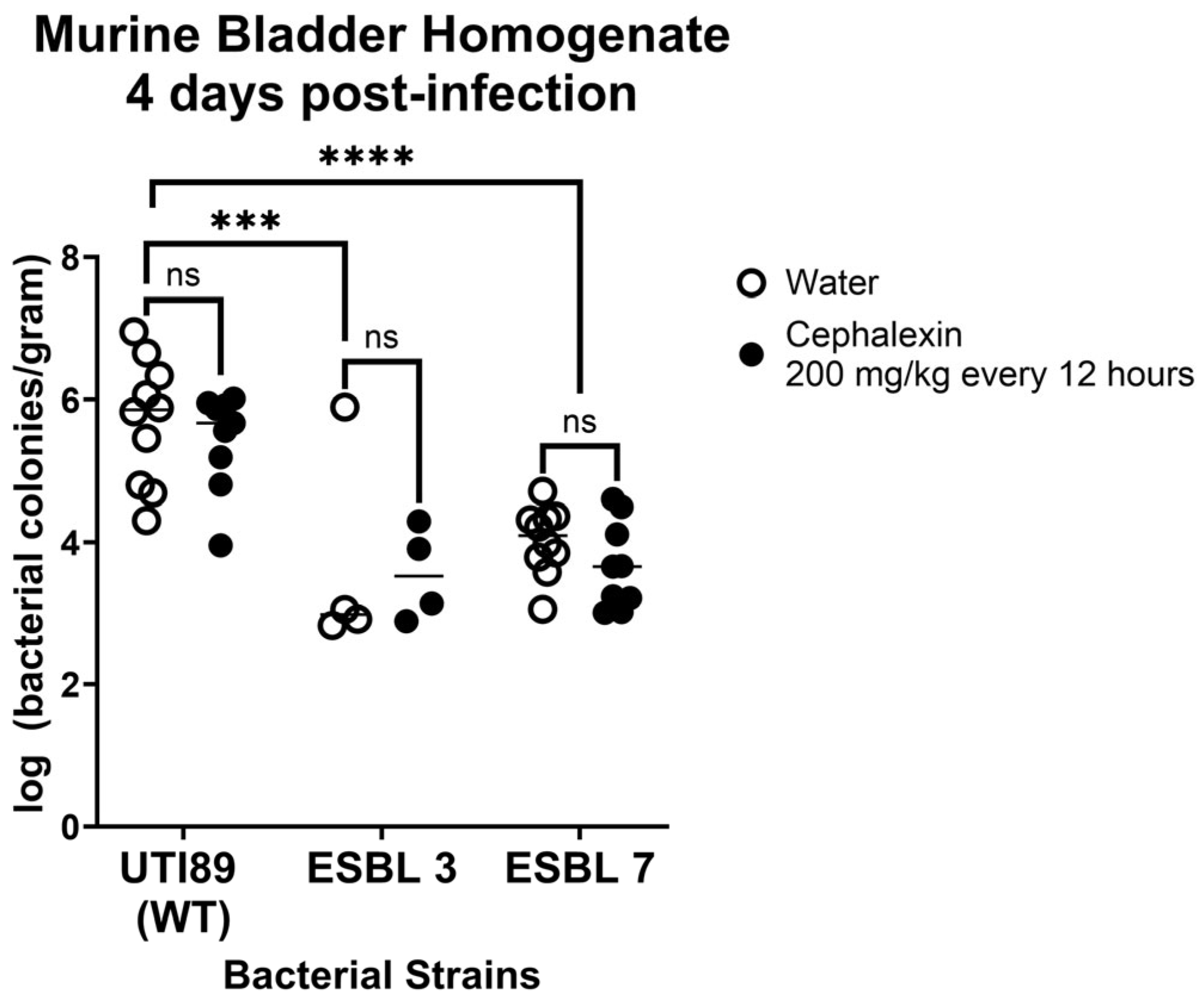

8.3. Results

8.3.1. In Vitro Activities of Cephalexin and LL-37 Against ESBL UPEC

8.3.2. Cephalexin Treatment Fails to Reduce Bacterial Burden in Murine UTI Model

9. Discussion

10. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UTI | Urinary tract infection |

| UPEC | Uropathogenic Escherichia coli |

| ESBL | Extended-spectrum β-lactamases |

| LL-37 | Human cathelicidin |

| ED | Emergency departments |

| IBCs | Intracellular bacterial communities |

| AMPs | Antimicrobial peptides |

| CAKUT | Congenital abnormalities of the kidney and urinary tract |

| VUR | Vesicourethral reflex |

| AAP | American Academy of Pediatrics |

| TMP-SMX | Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole |

| IDSA | Infectious Diseases Society of America |

| ESBL-E | ESBL-Enterobacterales |

| PBPs | Penicillin binding proteins |

| MRSA | Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus |

| CLSI | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute |

| MIC | Minimum inhibitory concentration |

| LB | Luria broth |

| LA | Luria agar |

| CA-MHB | Cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton Broth |

| RPMI | Roswell Park Memorial Institute 1640 |

| D-PBS | Dulbecco’s Phosphate-Buffered Saline |

| SU | Synthetic urine |

| FICI | Fractional inhibitory concentration index |

References

- Collingwood, J.D.; Yarbrough, A.H.; Boppana, S.B.; Dangle, P.P. Increasing Prevalence of Pediatric Community-Acquired UTI by Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing E. coli: Cause for Concern. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2023, 42, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachvanichsanong, P.; McNeil, E.B.; Dissaneewate, P. Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae Urinary Tract Infections. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 149, e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, N.; Morone, N.E.; Bost, J.E.; Farrell, M.H. Prevalence of Urinary Tract Infection in Childhood: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2008, 27, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marsh, M.C.; Junquera, G.Y.; Stonebrook, E.; Spencer, J.D.; Watson, J.R. Urinary Tract Infections in Children. Pediatr. Rev. 2024, 45, 260–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, D.; Wang, M.E.; Dahlen, A.; Liao, Y.; Saunders, A.C.; Coon, E.R.; Schroeder, A.R. Incidence of Pediatric Urinary Tract Infections before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw. Open 2024, 7, e2350061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, J.-W.; Liu, C.-S.; Tsai, H.-L. Vesicoureteral Reflux in Children with Urinary Tract Infections in the Inpatient Setting in Taiwan. Clin. Epidemiol. 2022, 14, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edlin, R.S.; Shapiro, D.J.; Hersh, A.L.; Copp, H.L. Antibiotic Resistance Patterns of Outpatient Pediatric Urinary Tract Infections. J. Urol. 2013, 190, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean-Baptiste, N.; Benjamin, D.K., Jr.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M.; Fowler, V.G., Jr.; Laughon, M.; Clark, R.H.; Smith, P.B. Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcal Infections in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2011, 32, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brook, I. Urinary Tract Infection Caused by Group-B Streptococcus in Infancy and Childhood. Urology 1981, 17, 428–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Luhidan, L.; Madani, A.; Albanyan, E.A.; Al Saif, S.; Nasef, M.; AlJohani, S.; Madkhali, A.; Al Shaalan, M.; Alalola, S. Neonatal Group B Streptococcal Infection in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Saudi Arabia: A 13-Year Experience. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2019, 38, 731–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginsburg, C.M. Comparative Pharmacokinetics of Cefadroxil, Cefaclor, Cephalexin and Cephradine in Infants and Children. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 1982, 10, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subcommittee On Urinary Tract Infection; Roberts, K.B.; Downs, S.M.; Finnell, S.M.E.; Hellerstein, S.; Shortliffe, L.D.; Wald, E.R.; Zerin, J.M. Reaffirmation of AAP Clinical Practice Guideline: The Diagnosis and Management of the Initial Urinary Tract Infection in Febrile Infants and Young Children 2-24 Months of Age. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20163026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamma, P.D.; Heil, E.L.; Justo, J.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Satlin, M.J.; Bonomo, R.A. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2024 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, ciae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawat, D.; Nair, D. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamases in Gram Negative Bacteria. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2010, 2, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papp-Wallace, K.M.; Endimiani, A.; Taracila, M.A.; Bonomo, R.A. Carbapenems: Past, Present, and Future. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4943–4960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas-Chanoine, M.-H.; Bertrand, X.; Madec, J.-Y. Escherichia coli ST131, an Intriguing Clonal Group. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 543–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topaloglu, R.; Er, I.; Dogan, B.G.; Bilginer, Y.; Ozaltin, F.; Besbas, N.; Ozen, S.; Bakkaloglu, A.; Gur, D. Risk Factors in Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections Caused by ESBL-Producing Bacteria in Children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2010, 25, 919–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotis, J.; Printza, N. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Bacteria in Children: A Matched Case-Control Study. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2013, 55, 671–674. [Google Scholar]

- Dayan, M.; Dabbah, H. Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Community-Acquired Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase Producing and Non-Producing Bacteria: A Comparative Study. J. Pediatr. 2013, 163, 1417–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, N.; Chen, H. Rise of Community-Onset Urinary Tract Infection Caused by Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli in Children. Immunol. Infect. 2014, 47, 399–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aksu, N.Y.; Ekinci, Z. Childhood Urinary Tract Infections Caused Be Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Bacteria: Risk Factors and Empiric Therapy. Pediatr. Int. 2017, 59, 176–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kizilca, O.; Siraneci, R.; Yilmaz, A.; Hatipoglu, N.; Ozturk, E.; Kiyak, A.; Ozkok, D. Risk Factors for Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infection Caused by ESBL-Producing Bacteria in Children. Pediatr. Int. 2012, 54, 858–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacmel, L.; Timsit, S.; Ferroni, A.; Auregan, C.; Angoulvant, F.; Chéron, G. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Bacteria Caused Less than 5% of Urinary Tract Infections in a Paediatric Emergency Centre. Acta Paediatr. 2016, 106, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna-Wakim, R.H.; Ghanem, S.T.; El Helou, M.W.; Khafaja, S.A.; Shaker, R.A.; Hassan, S.A.; Saad, R.K.; Hedari, C.P.; Khinkarly, R.W.; Hajar, F.M.; et al. Epidemiology and Characteristics of Urinary Tract Infections in Children and Adolescents. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2015, 5, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wragg, R.; Harris, A.; Patel, M.; Robb, A.; Chandran, H.; McCarthy, L. Extended Spectrum Beta Lactamase (ESBL) Producing Bacteria Urinary Tract Infections and Complex Pediatric Urology. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2017, 52, 286–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Megged, O. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Bacteria Causing Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections in Children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2014, 29, 1583–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saperston, K.N.; Shapiro, D.J.; Hersh, A.L.; Copp, H.L. A Comparison of Inpatient versus Outpatient Resistance Patterns of Pediatric Urinary Tract Infection. J. Urol. 2014, 191, 1608–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, L.K.; Braykov, N.P.; Weinstein, R.A.; Laxminarayan, R. CDC Epicenters Prevention Program Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing and Third-Generation Cephalosporin-Resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Children: Trends in the United States, 1999-2011. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2014, 3, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuta, T.; Shoji, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Saitoh, A. Treatment of Pyelonephritis Caused by Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2013, 32, 417–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tratselas, A.; Iosifidis, E.; Ioannidou, M.; Saoulidis, S.; Kollios, K.; Antachopoulos, C.; Sofianou, D.; Roilides, E.J. Outcome of Urinary Tract Infections Caused by Extended Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Children. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2011, 30, 707–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toubiana, J.; Timsit, S.; Ferroni, A.; Grasseau, M.; Nassif, X.; Lortholary, O.; Zahar, J.-R.; Chalumeau, M. Community-Onset Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae Invasive Infections in Children in a University Hospital in France. Medicine 2016, 95, e3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhi, F.; Jung, C.; Timsit, S.; Levy, C.; Biscardi, S.; Lorrot, M.; Grimprel, E.; Hees, L.; Craiu, I.; Galerne, A.; et al. Febrile Urinary-Tract Infection Due to Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Enterobacteriaceae in Children: A French Prospective Multicenter Study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyun, H.S.; Kim, J.H.; Cho, M.H.; Park, E.; Ha, I.-S.; Cheong, H.I.; Kang, H.G. Low Relapse Rate of Urinary Tract Infections from Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase-Producing Bacteria in Young Children. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2019, 34, 2399–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.E.; Lee, V.; Greenhow, T.L.; Beck, J.; Bendel-Stenzel, M.; Hames, N.; McDaniel, C.E.; King, E.E.; Sherry, W.; Parmar, D.; et al. Clinical Response to Discordant Therapy in Third-Generation Cephalosporin-Resistant UTIs. Pediatrics 2020, 145, e20191608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamas, V.; Shah, S.; Hollenbach, K.A.; Kanegaye, J.T. Emergence of Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Pathogens in Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections among Infants at a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr. Emerg. Care 2022, 38, e1053–e1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duraiswamy, S.; Chee, J.L.Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, E.; Lees, K.; Chen, S.L. Purification of Intracellular Bacterial Communities during Experimental Urinary Tract Infection Reveals an Abundant and Viable Bacterial Reservoir. Infect. Immun. 2018, 86, e00740-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zasloff, M. Antimicrobial Peptides, Innate Immunity, and the Normally Sterile Urinary Tract. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007, 18, 2810–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.D.; Schwaderer, A.L.; Becknell, B.; Watson, J.; Hains, D.S. The Innate Immune Response during Urinary Tract Infection and Pyelonephritis. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2014, 29, 1139–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.M.; Townes, C.L.; Hall, J.; Pickard, R.S. Maintaining a Sterile Urinary Tract: The Role of Antimicrobial Peptides. J. Urol. 2009, 182, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chromek, M.; Slamová, Z.; Bergman, P.; Kovács, L.; Podracká, L.; Ehrén, I.; Hökfelt, T.; Gudmundsson, G.H.; Gallo, R.L.; Agerberth, B.; et al. The Antimicrobial Peptide Cathelicidin Protects the Urinary Tract against Invasive Bacterial Infection. Nat. Med. 2006, 12, 636–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwaderer, A.L.; Wang, H.; Kim, S.; Kline, J.M.; Liang, D.; Brophy, P.D.; McHugh, K.M.; Tseng, G.C.; Saxena, V.; Barr-Beare, E.; et al. Polymorphisms in α-Defensin-Encoding DEFA1A3 Associate with Urinary Tract Infection Risk in Children with Vesicoureteral Reflux. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2016, 27, 3175–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, J.D.; Hains, D.S.; Porter, E.; Bevins, C.L.; DiRosario, J.; Becknell, B.; Wang, H.; Schwaderer, A.L. Human Alpha Defensin 5 Expression in the Human Kidney and Urinary Tract. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e31712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valore, E.V.; Park, C.H.; Quayle, A.J.; Wiles, K.R.; McCray, P.B., Jr.; Ganz, T. Human Beta-Defensin-1: An Antimicrobial Peptide of Urogenital Tissues. J. Clin. Investig. 1998, 101, 1633–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, J.D.; Schwaderer, A.L.; Dirosario, J.D.; McHugh, K.M.; McGillivary, G.; Justice, S.S.; Carpenter, A.R.; Baker, P.B.; Harder, J.; Hains, D.S. Ribonuclease 7 Is a Potent Antimicrobial Peptide within the Human Urinary Tract. Kidney Int. 2011, 80, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chromek, M. The Role of the Antimicrobial Peptide Cathelicidin in Renal Diseases. Pediatr. Nephrol. 2015, 30, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-T.; Nestel, F.P.; Bourdeau, V.; Nagai, Y.; Wang, Q.; Liao, J.; Tavera-Mendoza, L.; Lin, R.; Hanrahan, J.W.; Mader, S.; et al. Cutting Edge: 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Is a Direct Inducer of Antimicrobial Peptide Gene Expression. J. Immunol. 2004, 173, 2909–2912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koon, H.W.; Shih, D.Q.; Chen, J.; Bakirtzi, K.; Hing, T.C.; Law, I.; Ho, S.; Ichikawa, R.; Zhao, D.; Xu, H.; et al. Cathelicidin Signaling via the Toll-like Receptor Protects against Colitis in Mice. Gastroenterology 2011, 141, 1852–1863.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.T.; Stenger, S.; Li, H.; Wenzel, L.; Tan, B.H.; Krutzik, S.R.; Ochoa, M.T.; Schauber, J.; Wu, K.; Meinken, C.; et al. Toll-like Receptor Triggering of a Vitamin D-Mediated Human Antimicrobial Response. Science 2006, 311, 1770–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Zhang, G.; Minton, J.E.; Ross, C.R.; Blecha, F. Regulation of Cathelicidin Gene Expression: Induction by Lipopolysaccharide, Interleukin-6, Retinoic Acid, and Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhimurium Infection. Infect. Immun. 2000, 68, 5552–5558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peric, M.; Koglin, S.; Kim, S.-M.; Morizane, S.; Besch, R.; Prinz, J.C.; Ruzicka, T.; Gallo, R.L.; Schauber, J. IL-17A Enhances Vitamin D3-Induced Expression of Cathelicidin Antimicrobial Peptide in Human Keratinocytes. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 8504–8512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, O.; Arnljots, K.; Cowland, J.B.; Bainton, D.F.; Borregaard, N. The Human Antibacterial Cathelicidin, HCAP-18, Is Synthesized in Myelocytes and Metamyelocytes and Localized to Specific Granules in Neutrophils. Blood 1997, 90, 2796–2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, O.E.; Follin, P.; Johnsen, A.H.; Calafat, J.; Tjabringa, G.S.; Hiemstra, P.S.; Borregaard, N. Human Cathelicidin, HCAP-18, Is Processed to the Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 by Extracellular Cleavage with Proteinase 3. Blood 2001, 97, 3951–3959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamasaki, K.; Schauber, J.; Coda, A.; Lin, H.; Dorschner, R.A.; Schechter, N.M.; Bonnart, C.; Descargues, P.; Hovnanian, A.; Gallo, R.L. Kallikrein-Mediated Proteolysis Regulates the Antimicrobial Effects of Cathelicidins in Skin. FASEB J. 2006, 20, 2068–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, J.; Cho, Y.; Dinh, N.N.; Waring, A.J.; Lehrer, R.I. Activities of LL-37, a Cathelin-Associated Antimicrobial Peptide of Human Neutrophils. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 2206–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-García, B.; Lee, P.H.A.; Yamasaki, K.; Gallo, R.L. Anti-Fungal Activity of Cathelicidins and Their Potential Role in Candida Albicans Skin Infection. J. Investig Dermatol. 2005, 125, 108–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- den Hertog, A.L.; van Marle, J.; van Veen, H.A.; Van’t Hof, W.; Bolscher, J.G.M.; Veerman, E.C.I.; Nieuw Amerongen, A.V. Candidacidal Effects of Two Antimicrobial Peptides: Histatin 5 Causes Small Membrane Defects, but LL-37 Causes Massive Disruption of the Cell Membrane. Biochem. J. 2005, 388, 689–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas Boas, L.C.P.; de Lima, L.M.P.; Migliolo, L.; Mendes, G.D.S.; de Jesus, M.G.; Franco, O.L.; Silva, P.A. Linear Antimicrobial Peptides with Activity against Herpes Simplex Virus 1 and Aichi Virus: AMPs Against HSV 1 and Aichi Virus. Biopolymers 2017, 108, e22871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Tecle, T.; Verma, A.; Crouch, E.; White, M.; Hartshorn, K.L. The Human Cathelicidin LL-37 Inhibits Influenza A Viruses through a Mechanism Distinct from That of Surfactant Protein D or Defensins. J. Gen. Virol. 2013, 94, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Siman-Tov, G.; Keck, F.; Kortchak, S.; Bakovic, A.; Risner, K.; Lu, T.K.; Bhalla, N.; de la Fuente-Nunez, C.; Narayanan, A. Human Cathelicidin Peptide LL-37 as a Therapeutic Antiviral Targeting Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis Virus Infections. Antiviral Res. 2019, 164, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marr, A.K.; Cen, S.; Hancock, R.E.W.; McMaster, W.R. Identification of Synthetic and Natural Host Defense Peptides with Leishmanicidal Activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 2484–2491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico-Mata, R.; De Leon-Rodriguez, L.M.; Avila, E.E. Effect of Antimicrobial Peptides Derived from Human Cathelicidin LL-37 on Entamoeba histolytica Trophozoites. Exp. Parasitol. 2013, 133, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancho-Vaello, E.; Gil-Carton, D.; François, P.; Bonetti, E.-J.; Kreir, M.; Pothula, K.R.; Kleinekathöfer, U.; Zeth, K. The Structure of the Antimicrobial Human Cathelicidin LL-37 Shows Oligomerization and Channel Formation in the Presence of Membrane Mimics. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sancho-Vaello, E.; François, P.; Bonetti, E.-J.; Lilie, H.; Finger, S.; Gil-Ortiz, F.; Gil-Carton, D.; Zeth, K. Structural Remodeling and Oligomerization of Human Cathelicidin on Membranes Suggest Fibril-like Structures as Active Species. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sochacki, K.A.; Barns, K.J.; Bucki, R.; Weisshaar, J.C. Real-Time Attack on Single Escherichia coli Cells by the Human Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2011, 108, E77–E81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Mohapatra, S.; Weisshaar, J.C. Rigidification of the Escherichia coli Cytoplasm by the Human Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 Revealed by Superresolution Fluorescence Microscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 1017–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chongsiriwatana, N.P.; Lin, J.S.; Kapoor, R.; Wetzler, M.; Rea, J.A.C.; Didwania, M.K.; Contag, C.H.; Barron, A.E. Intracellular Biomass Flocculation as a Key Mechanism of Rapid Bacterial Killing by Cationic, Amphipathic Antimicrobial Peptides and Peptoids. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 16718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.; Yang, Z.; Weisshaar, J.C. Oxidative Stress Induced in E. coli by the Human Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overhage, J.; Campisano, A.; Bains, M.; Torfs, E.C.W.; Rehm, B.H.A.; Hancock, R.E.W. Human Host Defense Peptide LL-37 Prevents Bacterial Biofilm Formation. Infect. Immun. 2008, 76, 4176–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kai-Larsen, Y.; Lüthje, P.; Chromek, M.; Peters, V.; Wang, X.; Holm, A.; Kádas, L.; Hedlund, K.-O.; Johansson, J.; Chapman, M.R.; et al. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli Modulates Immune Responses and Its Curli Fimbriae Interact with the Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37. PLoS Pathog. 2010, 6, e1001010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; McLean, D.T.F.; Linden, G.J.; McAuley, D.F.; McMullan, R.; Lundy, F.T. The Naturally Occurring Host Defense Peptide, LL-37, and Its Truncated Mimetics KE-18 and KR-12 Have Selected Biocidal and Antibiofilm Activities Against Candida albicans, Staphylococcus aureus, and Escherichia coli In Vitro. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hell, E.; Giske, C.G.; Nelson, A.; Römling, U.; Marchini, G. Human Cathelicidin Peptide LL37 Inhibits Both Attachment Capability and Biofilm Formation of Staphylococcus epidermidis. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2010, 50, 211–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sol, A.; Ginesin, O.; Chaushu, S.; Karra, L.; Coppenhagen-Glazer, S.; Ginsburg, I.; Bachrach, G. LL-37 Opsonizes and Inhibits Biofilm Formation of Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans at Subbactericidal Concentrations. Infect. Immun. 2013, 81, 3577–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Chen, Q.; Schmidt, A.P.; Anderson, G.M.; Wang, J.M.; Wooters, J.; Oppenheim, J.J.; Chertov, O. LL-37, the Neutrophil Granule- and Epithelial Cell-Derived Cathelicidin, Utilizes Formyl Peptide Receptor-like 1 (FPRL1) as a Receptor to Chemoattract Human Peripheral Blood Neutrophils, Monocytes, and T Cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000, 192, 1069–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Cherryholmes, G.; Chang, F.; Rose, D.M.; Schraufstatter, I.; Shively, J.E. Evidence That Cathelicidin Peptide LL-37 May Act as a Functional Ligand for CXCR2 on Human Neutrophils. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009, 39, 3181–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elssner, A.; Duncan, M.; Gavrilin, M.; Wewers, M.D. A Novel P2X7 Receptor Activator, the Human Cathelicidin-Derived Peptide LL37, Induces IL-1 Beta Processing and Release. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 4987–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, M.; Soehnlein, O.; Tang, X.; van der Does, A.M.; Smedler, E.; Uhlén, P.; Lindbom, L.; Agerberth, B.; Haeggström, J.Z. Cathelicidin LL-37 Induces Time-Resolved Release of LTB4 and TXA2 by Human Macrophages and Triggers Eicosanoid Generation in Vivo. FASEB J. 2014, 28, 3456–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, A.; Berends, E.T.M.; Nerlich, A.; Molhoek, E.M.; Gallo, R.L.; Meerloo, T.; Nizet, V.; Naim, H.Y.; von Köckritz-Blickwede, M. The Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 Facilitates the Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps. Biochem. J. 2014, 464, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowdish, D.M.E.; Davidson, D.J.; Speert, D.P.; Hancock, R.E.W. The Human Cationic Peptide LL-37 Induces Activation of the Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase and P38 Kinase Pathways in Primary Human Monocytes. J. Immunol. 2004, 172, 3758–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minns, D.; Smith, K.J.; Alessandrini, V.; Hardisty, G.; Melrose, L.; Jackson-Jones, L.; MacDonald, A.S.; Davidson, D.J.; Gwyer Findlay, E. The Neutrophil Antimicrobial Peptide Cathelicidin Promotes Th17 Differentiation. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agier, J.; Różalska, S.; Wiktorska, M.; Żelechowska, P.; Pastwińska, J.; Brzezińska-Błaszczyk, E. The RLR/NLR Expression and pro-Inflammatory Activity of Tissue Mast Cells Are Regulated by Cathelicidin LL-37 and Defensin HBD-2. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 11750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lai, Y.; Chen, W.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Jin, M.; Yu, B. LL-37-Induced Human Mast Cell Activation through G Protein-Coupled Receptor MrgX2. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2017, 49, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiao, D.; Wong, C.-K.; Tsang, M.S.-M.; Chu, I.M.-T.; Liu, D.; Zhu, J.; Chu, M.; Lam, C.W.-K. Activation of Eosinophils Interacting with Bronchial Epithelial Cells by Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37: Implications in Allergic Asthma. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjabringa, G.S.; Ninaber, D.K.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Rabe, K.F.; Hiemstra, P.S. Human Cathelicidin LL-37 Is a Chemoattractant for Eosinophils and Neutrophils That Acts via Formyl-Peptide Receptors. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2006, 140, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altieri, A.; Marshall, C.L.; Ramotar, P.; Lloyd, D.; Hemshekhar, M.; Spicer, V.; van der Does, A.M.; Mookherjee, N. Human Host Defense Peptide LL-37 Suppresses TNFα-Mediated Matrix Metalloproteinases MMP9 and MMP13 in Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells. J. Innate Immun. 2024, 16, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tjabringa, G.S.; Aarbiou, J.; Ninaber, D.K.; Drijfhout, J.W.; Sørensen, O.E.; Borregaard, N.; Rabe, K.F.; Hiemstra, P.S. The Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 Activates Innate Immunity at the Airway Epithelial Surface by Transactivation of the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor. J. Immunol. 2003, 171, 6690–6696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lande, R.; Gregorio, J.; Facchinetti, V.; Chatterjee, B.; Wang, Y.-H.; Homey, B.; Cao, W.; Wang, Y.-H.; Su, B.; Nestle, F.O.; et al. Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Sense Self-DNA Coupled with Antimicrobial Peptide. Nature 2007, 449, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Meng, P.; Han, Y.; Shen, C.; Li, B.; Hakim, M.A.; Zhang, X.; Lu, Q.; Rong, M.; Lai, R. Mitochondrial DNA-LL-37 Complex Promotes Atherosclerosis by Escaping from Autophagic Recognition. Immunity 2015, 43, 1137–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.Y.; Zhang, C.; Di Domizio, J.; Jin, F.; Connell, W.; Hung, M.; Malkoff, N.; Veksler, V.; Gilliet, M.; Ren, P.; et al. Helical Antimicrobial Peptides Assemble into Protofibril Scaffolds That Present Ordered DsDNA to TLR9. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, A.; Völlger, L.; Berends, E.T.M.; Molhoek, E.M.; Stapels, D.A.C.; Midon, M.; Friães, A.; Pingoud, A.; Rooijakkers, S.H.M.; Gallo, R.L.; et al. Novel Role of the Antimicrobial Peptide LL-37 in the Protection of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps against Degradation by Bacterial Nucleases. J. Innate Immun. 2014, 6, 860–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.L.; Dynesen, P.; Larsen, P.; Jakobsen, L.; Andersen, P.S.; Frimodt-Møller, N. Role of Urinary Cathelicidin LL-37 and Human β-Defensin 1 in Uncomplicated Escherichia coli Urinary Tract Infections. Infect. Immun. 2014, 82, 1572–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oottamasathien, S.; Jia, W.; McCoard, L.; Slack, S.; Zhang, J.; Skardal, A.; Job, K.; Kennedy, T.P.; Dull, R.O.; Prestwich, G.D. A Murine Model of Inflammatory Bladder Disease: Cathelicidin Peptide Induced Bladder Inflammation and Treatment with Sulfated Polysaccharides. J. Urol. 2011, 186, 1684–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danka, E.S.; Hunstad, D.A. Cathelicidin Augments Epithelial Receptivity and Pathogenesis in Experimental Escherichia coli Cystitis. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 211, 1164–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, Y.; Kulkarni, N.N.; Takahashi, T.; Alimohamadi, H.; Dokoshi, T.; Liu, E.L.; Shia, M.; Numata, T.; Luo, E.W.; Gombart, A.F.; et al. Increased LL37 in Psoriasis and Other Inflammatory Disorders Promotes Low-Density Lipoprotein Uptake and Atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2024, 134, e172578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanda, N.; Ishikawa, T.; Kamata, M.; Tada, Y.; Watanabe, S. Increased Serum Leucine, Leucine-37 Levels in Psoriasis: Positive and Negative Feedback Loops of Leucine, Leucine-37 and pro- or Anti-Inflammatory Cytokines. Hum. Immunol. 2010, 71, 1161–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.W.; Ha, J.M.; Cho, E.B.; Jin, J.K.; Park, E.J.; Park, H.R.; Kang, H.J.; Ko, S.H.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, K.J. A Study on Vitamin D and Cathelicidin Status in Patients with Rosacea: Serum Level and Tissue Expression. Ann. Dermatol. 2018, 30, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, C.W.; Al-Maleki, A.R.; Vadivelu, J.; Danaee, M.; Sockalingam, S.; Baharuddin, N.A.; Vaithilingam, R.D. Salivary and Serum Cathelicidin LL-37 Levels in Subjects with Rheumatoid Arthritis and Chronic Periodontitis. Int. J. Rheum. Dis. 2020, 23, 1344–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herster, F.; Bittner, Z.; Archer, N.K.; Dickhöfer, S.; Eisel, D.; Eigenbrod, T.; Knorpp, T.; Schneiderhan-Marra, N.; Löffler, M.W.; Kalbacher, H.; et al. Neutrophil Extracellular Trap-Associated RNA and LL37 Enable Self-Amplifying Inflammation in Psoriasis. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.K.K.; Wong, C.C.M.; Li, Z.J.; Zhang, L.; Ren, S.X.; Cho, C.H. Cathelicidins in Inflammation and Tissue Repair: Potential Therapeutic Applications for Gastrointestinal Disorders. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2010, 31, 1118–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yu, F.-S.X. LL-37 via EGFR Transactivation to Promote High Glucose-Attenuated Epithelial Wound Healing in Organ-Cultured Corneas. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 1891–1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaykhiev, R.; Beisswenger, C.; Kändler, K.; Senske, J.; Püchner, A.; Damm, T.; Behr, J.; Bals, R. Human Endogenous Antibiotic LL-37 Stimulates Airway Epithelial Cell Proliferation and Wound Closure. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005, 289, L842–L848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reijnders, T.D.Y.; Saris, A.; Schultz, M.J.; van der Poll, T. Immunomodulation by Macrolides: Therapeutic Potential for Critical Care. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, 619–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumitrescu, O.; Choudhury, P.; Boisset, S.; Badiou, C.; Bes, M.; Benito, Y.; Wolz, C.; Vandenesch, F.; Etienne, J.; Cheung, A.L.; et al. Beta-Lactams Interfering with PBP1 Induce Panton-Valentine Leukocidin Expression by Triggering SarA and Rot Global Regulators of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 3261–3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culić, O.; Eraković, V.; Cepelak, I.; Barisić, K.; Brajsa, K.; Ferencić, Z.; Galović, R.; Glojnarić, I.; Manojlović, Z.; Munić, V.; et al. Azithromycin Modulates Neutrophil Function and Circulating Inflammatory Mediators in Healthy Human Subjects. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002, 450, 277–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishizawa, K.; Suzuki, T.; Yamaya, M.; Jia, Y.X.; Kobayashi, S.; Ida, S.; Kubo, H.; Sekizawa, K.; Sasaki, H. Erythromycin Increases Bactericidal Activity of Surface Liquid in Human Airway Epithelial Cells. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2005, 289, L565–L573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartman, B.J.; Tomasz, A. Low-Affinity Penicillin-Binding Protein Associated with Beta-Lactam Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. J. Bacteriol. 1984, 158, 513–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, A.D.; Theisen, E.; Sauer, J.-D.; Nonejuie, P.; Olson, J.; Pogliano, J.; Sakoulas, G.; Nizet, V.; Proctor, R.A.; Rose, W.E. Penicillin Binding Protein 1 Is Important in the Compensatory Response of Staphylococcus aureus to Daptomycin-Induced Membrane Damage and Is a Potential Target for β-Lactam–Daptomycin Synergy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoulas, G.; Okumura, C.Y.; Thienphrapa, W.; Olson, J.; Nonejuie, P.; Dam, Q.; Dhand, A.; Pogliano, J.; Yeaman, M.R.; Hensler, M.E.; et al. Nafcillin Enhances Innate Immune-Mediated Killing of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 92, 139–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhand, A.; Bayer, A.S.; Pogliano, J.; Yang, S.-J.; Bolaris, M.; Nizet, V.; Wang, G.; Sakoulas, G. Use of Antistaphylococcal Beta-Lactams to Increase Daptomycin Activity in Eradicating Persistent Bacteremia Due to Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus: Role of Enhanced Daptomycin Binding. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 53, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, S.; Singh, C.; Plata, K.B.; Chanda, P.K.; Paul, A.; Riosa, S.; Rosato, R.R.; Rosato, A.E. β-Lactams Increase the Antibacterial Activity of Daptomycin against Clinical Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Strains and Prevent Selection of Daptomycin-Resistant Derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 6192–6200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaraswamy, M.; Lin, L.; Olson, J.; Sun, C.-F.; Nonejuie, P.; Corriden, R.; Döhrmann, S.; Ali, S.R.; Amaro, D.; Rohde, M.; et al. Standard Susceptibility Testing Overlooks Potent Azithromycin Activity and Cationic Peptide Synergy against MDR Stenotrophomonas maltophilia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1264–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulloa, E.R.; Kousha, A.; Tsunemoto, H.; Pogliano, J.; Licitra, C.; LiPuma, J.J.; Sakoulas, G.; Nizet, V.; Kumaraswamy, M. Azithromycin Exerts Bactericidal Activity and Enhances Innate Immune Mediated Killing of MDR Achromobacter xylosoxidans. Infect. Microbes Dis. 2020, 2, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Nonejuie, P.; Munguia, J.; Hollands, A.; Olson, J.; Dam, Q.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Rivera, H., Jr.; Corriden, R.; Rohde, M.; et al. Azithromycin Synergizes with Cationic Antimicrobial Peptides to Exert Bactericidal and Therapeutic Activity against Highly Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacterial Pathogens. EBioMedicine 2015, 2, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heesterbeek, D.A.C.; Martin, N.I.; Velthuizen, A.; Duijst, M.; Ruyken, M.; Wubbolts, R.; Rooijakkers, S.H.M.; Bardoel, B.W. Complement-Dependent Outer Membrane Perturbation Sensitizes Gram-Negative Bacteria to Gram-Positive Specific Antibiotics. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, I.; Said, D.G.; Nubile, M.; Mastropasqua, L.; Dua, H.S. Cathelicidin-Derived Synthetic Peptide Improves Therapeutic Potential of Vancomycin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herencias, C.; Álvaro-Llorente, L.; Ramiro-Martínez, P.; Fernández-Calvet, A.; Muñoz-Cazalla, A.; DelaFuente, J.; Graf, F.E.; Jaraba-Soto, L.; Castillo-Polo, J.A.; Cantón, R.; et al. β-Lactamase Expression Induces Collateral Sensitivity in Escherichia Coli. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A.; Pérez, A.; Ayala, J.A.; Mallo, S.; Rumbo-Feal, S.; Tomás, M.; Poza, M.; Bou, G. Expression of OXA-Type and SFO-1 β-Lactamases Induces Changes in Peptidoglycan Composition and Affects Bacterial Fitness. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 1877–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulvey, M.A.; Schilling, J.D.; Hultgren, S.J. Establishment of a Persistent Escherichia coli Reservoir during the Acute Phase of a Bladder Infection. Infect. Immun. 2001, 69, 4572–4579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, 4th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Malvern, PA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, T.; Keevil, C.W. A Simple Artificial Urine for the Growth of Urinary Pathogens. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 1997, 24, 203–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakoulas, G.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Kousha, A.; Nizet, V. Interaction of Antibiotics with Innate Host Defense Factors against Salmonella enterica Serotype Newport. mSphere 2017, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odds, F.C. Synergy, Antagonism, and What the Chequerboard Puts between Them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 52, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patras, K.A.; Coady, A.; Babu, P.; Shing, S.R.; Ha, A.D.; Rooholfada, E.; Brandt, S.L.; Geriak, M.; Gallo, R.L.; Nizet, V. Host Cathelicidin Exacerbates Group B Streptococcus Urinary Tract Infection. mSphere 2020, 5, e00932-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heithoff, D.M.; Barnes, L.V.; Mahan, S.P.; Fried, J.C.; Fitzgibbons, L.N.; House, J.K.; Mahan, M.J. Re-Evaluation of FDA-Approved Antibiotics with Increased Diagnostic Accuracy for Assessment of Antimicrobial Resistance. Cell Rep. Med. 2023, 4, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, H.; Seif, Y.; Sakoulas, G.; Olson, C.A.; Hefner, Y.; Anand, A.; Jones, Y.Z.; Szubin, R.; Palsson, B.O.; Nizet, V.; et al. Environmental Conditions Dictate Differential Evolution of Vancomycin Resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulvey, M.A.; Lopez-Boado, Y.S.; Wilson, C.L.; Roth, R.; Parks, W.C.; Heuser, J.; Hultgren, S.J. Induction and Evasion of Host Defenses by Type 1-Piliated Uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 1998, 282, 1494–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, H.R.; Billings, R.E.; McMahon, R.E. Metabolism of Cephalexin-14C in Mice and in Rats. J. Antibiot. 1969, 22, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veauthier, B.; Miller, M.V. Urinary Tract Infections in Young Children and Infants: Common Questions and Answers. Am. Fam. Physician 2020, 102, 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Hartstein, A.I.; Patrick, K.E.; Jones, S.R.; Miller, M.J.; Bryant, R.E. Comparison of Pharmacological and Antimicrobial Properties of Cefadroxil and Cephalexin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1977, 12, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, A.B.; Jacob, S. A Simple Practice Guide for Dose Conversion between Animals and Human. J. Basic Clin. Pharm. 2016, 7, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Health and Human Services; Food and Drug Administration; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for Industry: Estimating the Maximum Safe Starting Dose in Initial Clinical Trials for Therapeutics in Adult Healthy Volunteers: Pharmacology and Toxicology; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: Rockville, MD, USA, 2005.

- Blango, M.G.; Mulvey, M.A. Persistence of Uropathogenic Escherichia coli in the Face of Multiple Antibiotics. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 1855–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, R.S. The Pharmacology of Cephalexin. Postgrad. Med. J. 1983, 59, 16–27. [Google Scholar]

| Study | Type | N | Male % | Age, Median, IQR, Months | E. coli % | Discordant Antibiotics, n, % | Anatomic Abnormalities, n, % | Clinical Improvement in 48 h, n, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Katsuta et al. 2013 [29] | Retrospective | 54 | 30% | 28 months (92) | 100% | 32, 59.2% | 20, 37.0% | 24/32, 75% |

| Tratselas et al. 2011 [30] | Matched case–control | 28 | 20% | 2.25 (0.6–108) | 67.9% | 24, 85.7% | 24, 85.7% | 17/18, 94.4% |

| Toubiana et al. 2016 [31] | Retrospective | 82 | 53% | 1 (0.72–192) | 100% | 51, 62.2% | 44, 48.9% | |

| Madhi et al. 2018 [32] | Prospective | 301 | 44.5% | 12 (0.02–17.9) | 87.8% | 67, 22.3% ** | ||

| Hyun et al. 2019 [33] | Retrospective | 146 | 63% | 7.2 (0–24) | 80.1% | 109, 74.7% | 43, 29.5% | 97/109, 88.9% |

| Wang et al. 2020 [34] | Retrospective | 316 | 22% | 28.8 (7.2–78.0) | 98.7% | 316, 100% | 16, 5.1% †† | 192/230, 83.4% |

| Tamas et al. 2022 [35] | Retrospective | 45 | 37.8% | 5.42 | 93% | 41, 91.1% | 14, 31.1% |

| Strain Number | Patient Age/Sex | Clinical Course 1 | Cephalexin | LL-37 | Cephalexin + LL-37 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MIC (mg/L) | MIC (µM) | FICI 2 | ||||

| CA-MHB | RPMI + 10% LB | RPMI + 10% LB | RPMI + 10% LB | |||

| 3 | 17 yo, F | Improved | >256 | >256 | 8 | 2 |

| 6 | 17 yo, F | ND | >256 | >256 | 16 | 2 |

| 7 | 1 yo, F | Improved | >256 | >256 | 8 | 2 |

| 9 | 8 yo, F | ND | >256 | >256 | 8 | 2 |

| 15 | 4 yo, F | ND | >256 | >256 | 8 | 2 |

| 17 | 4 yo, F | ND | >256 | >256 | 4 | 2 |

| 18 | 16 yo, F | ND | >256 | >256 | 4 | 2 |

| 21 | 20 do, M | ND | >256 | >256 | 8 | 2 |

| Strain Number | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotic | 3 | 6 | 7 | 9 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 21 |

| Cephalexin | R | R | R | R | R | R | R | R |

| Amikacin | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Ciprofloxacin | S | S | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | S |

| Meropenem | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Nitrofurantoin | S | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

| Tobramycin | I | S | S | ND | ND | ND | S | S |

| Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | S | S | ND | S | S | S | ND | ND |

| Gentamicin | ND | S | S | ND | ND | ND | S | S |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tamas, V.; Ulloa, E.R.; Kumaraswamy, M.; Dahesh, S.; Zurich, R.; Nizet, V.; Coady, A. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli and Pediatric UTIs: A Review of the Literature and Selected Experimental Observations. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121284

Tamas V, Ulloa ER, Kumaraswamy M, Dahesh S, Zurich R, Nizet V, Coady A. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli and Pediatric UTIs: A Review of the Literature and Selected Experimental Observations. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121284

Chicago/Turabian StyleTamas, Vanessa, Erlinda R. Ulloa, Monika Kumaraswamy, Samira Dahesh, Raymond Zurich, Victor Nizet, and Alison Coady. 2025. "Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli and Pediatric UTIs: A Review of the Literature and Selected Experimental Observations" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121284

APA StyleTamas, V., Ulloa, E. R., Kumaraswamy, M., Dahesh, S., Zurich, R., Nizet, V., & Coady, A. (2025). Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-Producing Escherichia coli and Pediatric UTIs: A Review of the Literature and Selected Experimental Observations. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1284. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121284