Recent Advances in Endolysin Engineering

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Antimicrobial Resistance

1.2. Bacteriophage and Their Use as Antimicrobial Therapeutics

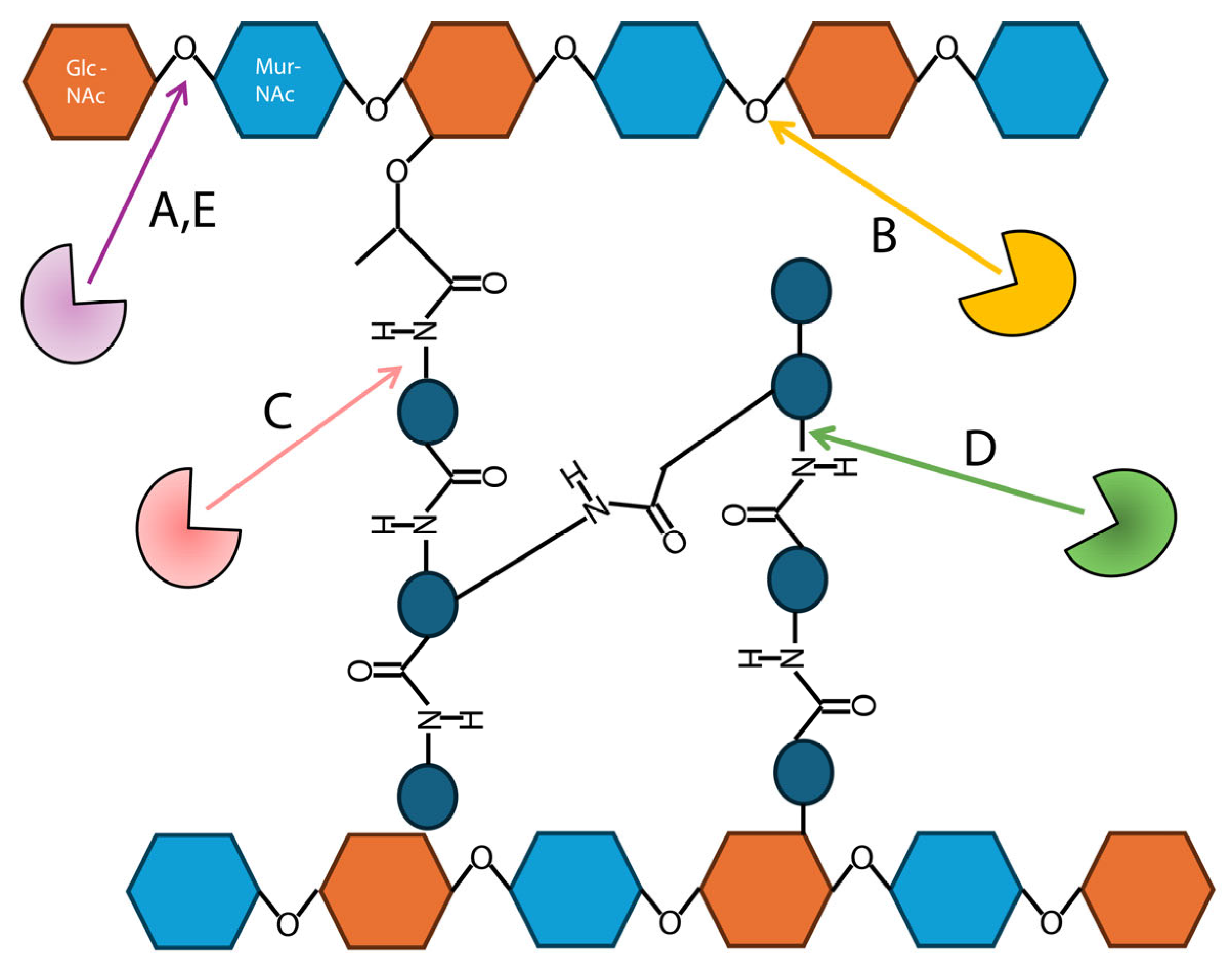

1.3. Endolysins and the Bacterial Cell Wall

1.4. Endolysin Structure and Catalysis

1.5. Endolysin Engineering

- Modification of endolysin catalytic sites [62].

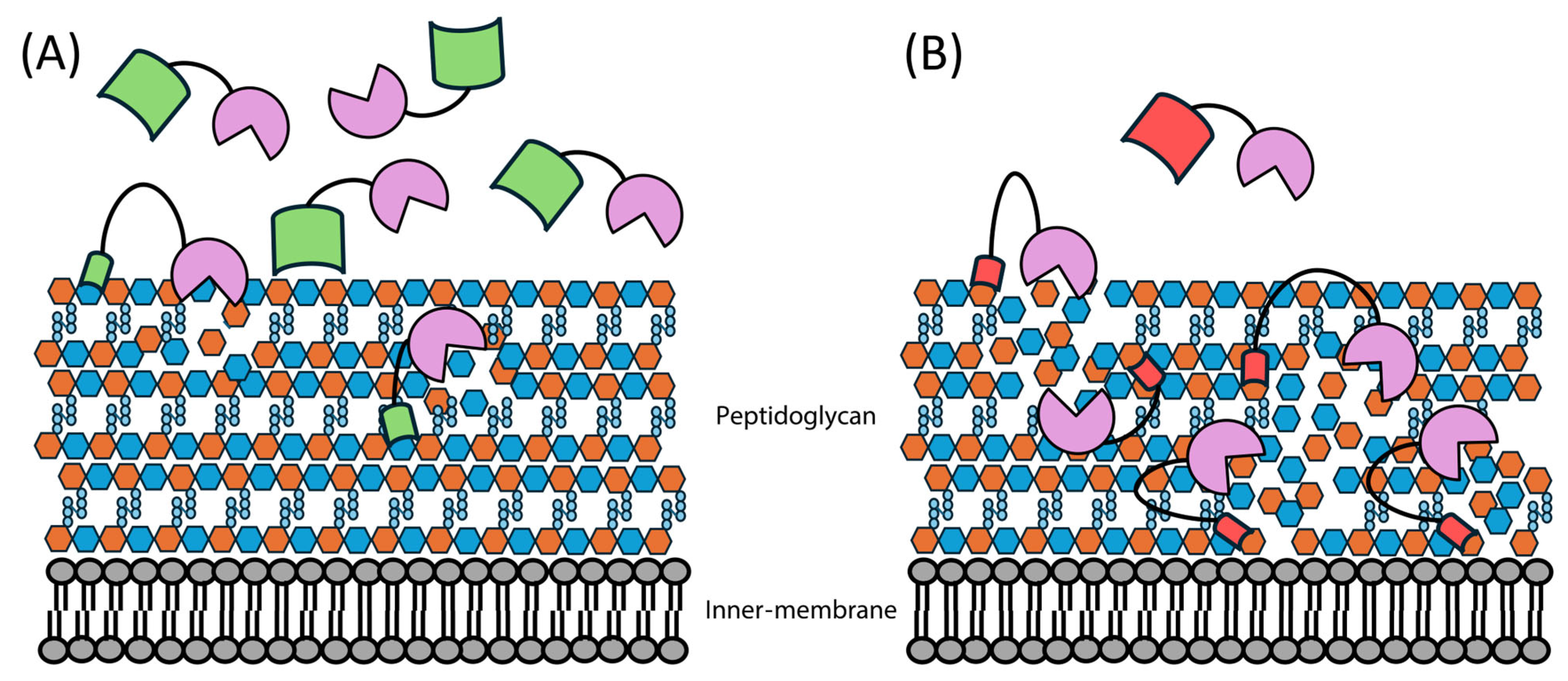

2. Fusion of Membrane Permeabilizing Peptides to Gram-Negative Targeting Endolysins

2.1. Overcoming the Outer Membrane Barrier

2.2. Artilysin Engineering to Enhance Endolysin Cell Killing

2.3. Future Directions for Artilysin Research

3. Swapping or Addition of Endolysin Domains

3.1. Overview of Endolysin Domain Swapping

3.2. Domain Swapping Effects on Antimicrobial Activity

3.3. Domain Replacement with Other Bacteriophage Proteins

3.4. Future Directions for Endolysin Domain-Swapping Engineering

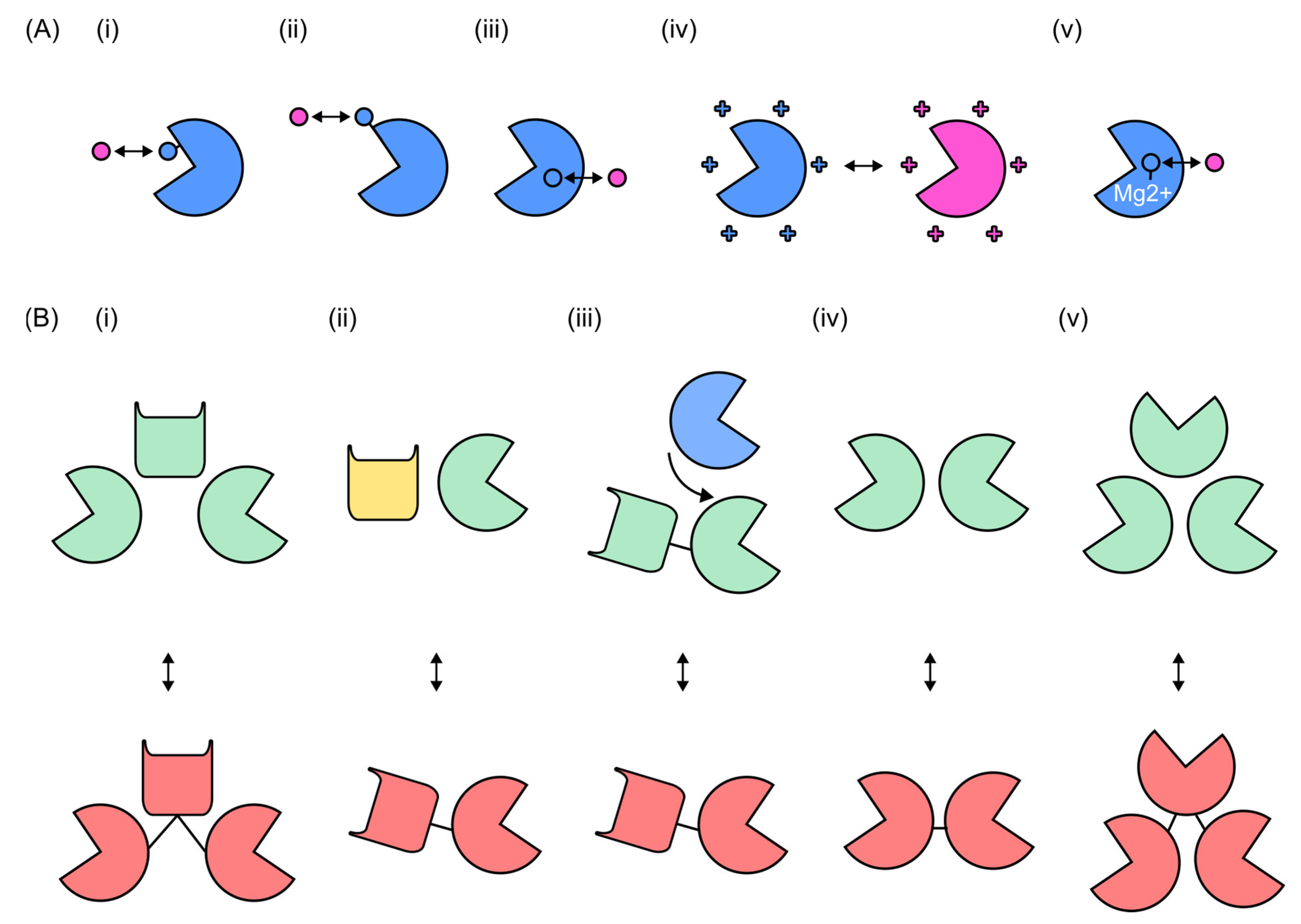

4. Modification of Endolysin Catalytic Sites

4.1. Endolysin Catalytic-Site Engineering in Clinical Use

4.2. Mutagenesis and Active-Site Modifications

4.3. Modular Strategies in Endolysin Catalytic-Site Engineering

4.4. Future Directions for Endolysin Catalytic-Site Engineering

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Gray, A.; Han, C.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations; Wellcome Trust: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Naghavi, M.; Vollset, S.E.; Ikuta, K.S.; Swetschinski, L.R.; Gray, A.P.; Wool, E.E.; Robles Aguilar, G.; Mestrovic, T.; Smith, G.; Han, C.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance 1990–2021: A Systematic Analysis with Forecasts to 2050. Lancet 2024, 404, 1199–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, N.R.; Hasso-Agopsowicz, M.; Kim, C.; Ma, Y.; Frost, I.; Abbas, K.; Aguilar, G.; Fuller, N.M.; Robotham, J.V.; Jit, M. The Global Economic Burden of Antibiotic Resistant Infections and the Potential Impact of Bacterial Vaccines: A Modelling Study. BMJ Glob. Health 2025, 10, e016249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, J.; Davies, D. Origins and Evolution of Antibiotic Resistance. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2010, 74, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, B.; Wang, W.; Arshad, M.I.; Khurshid, M.; Muzammil, S.; Rasool, M.H.; Nisar, M.A.; Alvi, R.F.; Aslam, M.A.; Qamar, M.U.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance: A Rundown of a Global Crisis. IDR 2018, 11, 1645–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riedel, S.; Beekmann, S.E.; Heilmann, K.P.; Richter, S.S.; Garcia-de-Lomas, J.; Ferech, M.; Goosens, H.; Doern, G.V. Antimicrobial Use in Europe and Antimicrobial Resistance in Streptococcus pneumoniae. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007, 26, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, T.M.; Chakraborty, A.J.; Khusro, A.; Zidan, B.R.M.; Mitra, S.; Emran, T.B.; Dhama, K.; Ripon, M.K.H.; Gajdács, M.; Sahibzada, M.U.K.; et al. Antibiotic Resistance in Microbes: History, Mechanisms, Therapeutic Strategies and Future Prospects. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 1750–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magiorakos, A.-P.; Srinivasan, A.; Carey, R.B.; Carmeli, Y.; Falagas, M.E.; Giske, C.G.; Harbarth, S.; Hindler, J.F.; Kahlmeter, G.; Olsson-Liljequist, B.; et al. Multidrug-Resistant, Extensively Drug-Resistant and Pandrug-Resistant Bacteria: An International Expert Proposal for Interim Standard Definitions for Acquired Resistance. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 268–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akova, M. Epidemiology of Antimicrobial Resistance in Bloodstream Infections. Virulence 2016, 7, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lister, P.D.; Wolter, D.J.; Hanson, N.D. Antibacterial-Resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Clinical Impact and Complex Regulation of Chromosomally Encoded Resistance Mechanisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2009, 22, 582–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jenkins, D.R. Nosocomial Infections and Infection Control. Medicine 2021, 49, 638–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frieri, M.; Kumar, K.; Boutin, A. Antibiotic Resistance. J. Infect. Public Health 2017, 10, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.-R.; Cho, I.; Jeong, B.; Lee, S. Strategies to Minimize Antibiotic Resistance. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2013, 10, 4274–4305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Payne, D.J.; Gwynn, M.N.; Holmes, D.J.; Pompliano, D.L. Drugs for Bad Bugs: Confronting the Challenges of Antibacterial Discovery. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007, 6, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clokie, M.R.; Millard, A.D.; Letarov, A.V.; Heaphy, S. Phages in Nature. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulakvelidze, A.; Alavidze, Z.; Morris, J.G. Bacteriophage Therapy. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2001, 45, 649–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedon, S.T.; Kuhl, S.J.; Blasdel, B.G.; Kutter, E.M. Phage Treatment of Human Infections. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 66–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, W.C. Bacteriophage Therapy. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 437–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandamme, E.J. Phage Therapy and Phage Control: To Be Revisited Urgently!! J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2014, 89, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loc-Carrillo, C.; Abedon, S.T. Pros and Cons of Phage Therapy. Bacteriophage 2011, 1, 111–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skurnik, M.; Pajunen, M.; Kiljunen, S. Biotechnological Challenges of Phage Therapy. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waldor, M.K.; Mekalanos, J.J. Lysogenic Conversion by a Filamentous Phage Encoding Cholera Toxin. Science 1996, 272, 1910–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petty, N.K.; Toribio, A.L.; Goulding, D.; Foulds, I.; Thomson, N.; Dougan, G.; Salmond, G.P.C. A Generalized Transducing Phage for the Murine Pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Microbiology 2007, 153, 2984–2988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel, B.; Moineau, S. CRISPR-Cas: An Efficient Tool for Genome Engineering of Virulent Bacteriophages. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, 9504–9513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrangou, R.; Fremaux, C.; Deveau, H.; Richards, M.; Boyaval, P.; Moineau, S.; Romero, D.A.; Horvath, P. CRISPR Provides Acquired Resistance Against Viruses in Prokaryotes. Science 2007, 315, 1709–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauconnier, A. Phage Therapy Regulation: From Night to Dawn. Viruses 2019, 11, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borysowski, J.; Weber-Dąbrowska, B.; Górski, A. Bacteriophage Endolysins as a Novel Class of Antibacterial Agents. Exp. Biol. Med. 2006, 231, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briers, Y.; Walmagh, M.; Van Puyenbroeck, V.; Cornelissen, A.; Cenens, W.; Aertsen, A.; Oliveira, H.; Azeredo, J.; Verween, G.; Pirnay, J.-P.; et al. Engineered Endolysin-Based “Artilysins” To Combat Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Pathogens. mBio 2014, 5, e01379-14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.C.; Schmelcher, M.; Rodriguez-Rubio, L.; Klumpp, J.; Pritchard, D.G.; Dong, S.; Donovan, D.M. Endolysins as Antimicrobials. In Advances in Virus Research; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2012; Volume 83, pp. 299–365. ISBN 978-0-12-394438-2. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, P.A.; Pootjes, C.F. Host-Bacteriophage Interaction in Agrobacterium tumefaciens III. Phage-Coded Endolysins. J. Virol. 1974, 13, 937–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Feng, C.; Ren, J.; Zhuang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Dong, K.; He, P.; Guo, X.; Qin, J. A Novel Antimicrobial Endolysin, LysPA26, against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 8, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.-H.; Park, D.-W.; Lim, J.-A.; Park, J.-H. Characterization of Staphylococcal Endolysin LysSAP33 Possessing Untypical Domain Composition. J. Microbiol. 2021, 59, 840–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paradis-Bleau, C.; Cloutier, I.; Lemieux, L.; Sanschagrin, F.; Laroche, J.; Auger, M.; Garnier, A.; Levesque, R.C. Peptidoglycan Lytic Activity of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Phage φKZ Gp144 Lytic Transglycosylase. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007, 266, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, J.M.; Nelson, D.; Fischetti, V.A. Rapid Killing of Streptococcus pneumoniae with a Bacteriophage Cell Wall Hydrolase. Science 2001, 294, 2170–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, R.; Nelson, D.; Fischetti, V.A. A Bacteriolytic Agent That Detects and Kills Bacillus anthracis. Nature 2002, 418, 884–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischetti, V.A. Bacteriophage Endolysins: A Novel Anti-Infective to Control Gram-Positive Pathogens. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 2010, 300, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer, M.; Vukov, N.; Scherer, S.; Loessner, M.J. The Murein Hydrolase of the Bacteriophage φ3626 Dual Lysis System Is Active against All Tested Clostridium perfringens Strains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2002, 68, 5311–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.J.; Coombes, D.; Manners, S.H.; Abeysekera, G.S.; Billington, C.; Dobson, R.C.J. The Molecular Basis for Escherichia coli O157:H7 Phage FAHEc1 Endolysin Function and Protein Engineering to Increase Thermal Stability. Viruses 2021, 13, 1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleifer, K.H.; Kandler, O. Peptidoglycan Types of Bacterial Cell Walls and Their Taxonomic Implications. Bacteriol. Rev. 1972, 36, 407–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Love, M.J.; Abeysekera, G.S.; Muscroft-Taylor, A.C.; Billington, C.; Dobson, R.C.J. On the Catalytic Mechanism of Bacteriophage Endolysins: Opportunities for Engineering. Biochim. Et Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Proteins Proteom. 2020, 1868, 140302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maciejewska, B.; Źrubek, K.; Espaillat, A.; Wiśniewska, M.; Rembacz, K.P.; Cava, F.; Dubin, G.; Drulis-Kawa, Z. Modular Endolysin of Burkholderia AP3 Phage Has the Largest Lysozyme-like Catalytic Subunit Discovered to Date and No Catalytic Aspartate Residue. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 14501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, B.; Yun, J.; Lim, J.-A.; Shin, H.; Heu, S.; Ryu, S. Characterization of LysB4, an Endolysin from the Bacillus cereus-Infecting Bacteriophage B4. BMC Microbiol. 2012, 12, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breijyeh, Z.; Jubeh, B.; Karaman, R. Resistance of Gram-Negative Bacteria to Current Antibacterial Agents and Approaches to Resolve It. Molecules 2020, 25, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loessner, M.J.; Gaeng, S.; Wendlinger, G.; Maier, S.K.; Scherer, S. The Two-Component Lysis System of Staphylococcus aureus Bacteriophage Twort: A Large TTG-Start Holin and an Associated Amidase Endolysin. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1998, 162, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasala, A.; Välkkilä, M.; Caldentey, J.; Alatossava, T. Genetic and Biochemical Characterization of the Lactobacillus delbrueckii Subsp. Lactis Bacteriophage LL-H Lysin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1995, 61, 4004–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phothichaisri, W.; Chankhamhaengdecha, S.; Janvilisri, T.; Nuadthaisong, J.; Phetruen, T.; Fagan, R.P.; Chanarat, S. Potential Role of the Host-Derived Cell-Wall Binding Domain of Endolysin CD16/50L as a Molecular Anchor in Preservation of Uninfected Clostridioides Difficile for New Rounds of Phage Infection. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e02361-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J.-H.; Kwon, J.-G.; O’Sullivan, D.J.; Ryu, S.; Lee, J.-H. Development of an Endolysin Enzyme and Its Cell Wall–Binding Domain Protein and Their Applications for Biocontrol and Rapid Detection of Clostridium perfringens in Food. Food Chem. 2021, 345, 128562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelcher, M.; Shabarova, T.; Eugster, M.R.; Eichenseher, F.; Tchang, V.S.; Banz, M.; Loessner, M.J. Rapid Multiplex Detection and Differentiation of Listeria Cells by Use of Fluorescent Phage Endolysin Cell Wall Binding Domains. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 5745–5756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, P.; García, J.; García, E.; Sánchez-Puelles, J.; López, R. Modular Organization of the Lytic Enzymes of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Its Bacteriophages. Gene 1990, 86, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saber, A.M.; Aghamollaei, H.; Esmaeili Gouvarchin Ghaleh, H.; Mohammadi, M.; Yaghoob Sehri, S.; Farnoosh, G. Design and Production of a Chimeric Enzyme with Efficient Antibacterial Properties on Staphylococcus aureus. Int. J. Pept. Res. Ther. 2024, 30, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Kim, J.; Son, B.; Ryu, S. Development of Advanced Chimeric Endolysin to Control Multidrug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus through Domain Shuffling. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 2081–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blázquez, B.; Fresco-Taboada, A.; Iglesias-Bexiga, M.; Menéndez, M.; García, P. PL3 Amidase, a Tailor-Made Lysin Constructed by Domain Shuffling with Potent Killing Activity against Pneumococci and Related Species. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, M.-J.; Lin, N.-T.; Hu, A.; Soo, P.-C.; Chen, L.-K.; Chen, L.-H.; Chang, K.-C. Antibacterial Activity of Acinetobacter baumannii Phage ϕAB2 Endolysin (LysAB2) against Both Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 90, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, H.; Vilas Boas, D.; Mesnage, S.; Kluskens, L.D.; Lavigne, R.; Sillankorva, S.; Secundo, F.; Azeredo, J. Structural and Enzymatic Characterization of ABgp46, a Novel Phage Endolysin with Broad Anti-Gram-Negative Bacterial Activity. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, M.; Tanji, Y.; Orito, Y.; Mizoguchi, K.; Soejima, A.; Unno, H. Functional Analysis of Antibacterial Activity of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens Phage Endolysin against Gram-Negative Bacteria. FEBS Lett. 2001, 500, 56–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, D.; Loomis, L.; Fischetti, V.A. Prevention and Elimination of Upper Respiratory Colonization of Mice by Group A Streptococci by Using a Bacteriophage Lytic Enzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 4107–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jado, I. Phage Lytic Enzymes as Therapy for Antibiotic-Resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae Infection in a Murine Sepsis Model. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 52, 967–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler, J.M.; Djurkovic, S.; Fischetti, V.A. Phage Lytic Enzyme Cpl-1 as a Novel Antimicrobial for Pneumococcal Bacteremia. Infect. Immun. 2003, 71, 6199–6204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briers, Y.; Walmagh, M.; Grymonprez, B.; Biebl, M.; Pirnay, J.-P.; Defraine, V.; Michiels, J.; Cenens, W.; Aertsen, A.; Miller, S.; et al. Art-175 Is a Highly Efficient Antibacterial against Multidrug-Resistant Strains and Persisters of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 3774–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, N.; Vasina, D.; Rubalsky, E.; Fursov, M.; Savinova, A.; Grigoriev, I.; Usachev, E.; Shevlyagina, N.; Zhukhovitsky, V.; Balabanyan, V.; et al. Modulation of Endolysin LysECD7 Bactericidal Activity by Different Peptide Tag Fusion. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.C.; Roach, D.R.; Chauhan, V.S.; Shen, Y.; Foster-Frey, J.; Powell, A.M.; Bauchan, G.; Lease, R.A.; Mohammadi, H.; Harty, W.J.; et al. Triple-Acting Lytic Enzyme Treatment of Drug-Resistant and Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 25063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmelcher, M.; Donovan, D.M.; Loessner, M.J. Bacteriophage Endolysins as Novel Antimicrobials. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7, 1147–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Z.; Raudonis, R.; Glick, B.R.; Lin, T.-J.; Cheng, Z. Antibiotic Resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Mechanisms and Alternative Therapeutic Strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 2019, 37, 177–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloutier, I.; Paradis-Bleau, C.; Giroux, A.-M.; Pigeon, X.; Arseneault, M.; Levesque, R.C.; Auger, M. Biophysical Studies of the Interactions between the Phage ϕKZ Gp144 Lytic Transglycosylase and Model Membranes. Eur. Biophys. J. 2010, 39, 263–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borysowski, J.; Górski, A. Fusion to Cell-Penetrating Peptides Will Enable Lytic Enzymes to Kill Intracellular Bacteria. Med. Hypotheses 2010, 74, 164–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonova, N.P.; Balabanyan, V.Y.; Tkachuk, A.P.; Makarov, V.V.; Gushchin, V.A. Physical and Chemical Properties of Recombinant KPP10 Phage Lysins and Their Antimicrobial Activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Bull. RSMU 2018, 1, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Zheng, Y.; Dai, J.; Zhou, J.; Yu, R.; Zhang, C. Design SMAP29-LysPA26 as a Highly Efficient Artilysin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa with Bactericidal and Antibiofilm Activity. Microbiol. Spectr. 2021, 9, e00546-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, T.; Meng, F.; Zhou, L.; Lu, F.; Bie, X.; Lu, Z.; Lu, Y. In Silico Development of Novel Chimeric Lysins with Highly Specific Inhibition against Salmonella by Computer-Aided Design. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 3751–3760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, J. Development of Highly Efficient Artilysins against Vibrio parahaemolyticus via Virtual Screening Assisted by Molecular Docking. Food Control 2023, 146, 109521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, T.; Liu, S.; Zou, P.; Yao, X.; Chen, Q.; Wei, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zheng, Y.; Yu, R. Create Artilysins from a Recombinant Library to Serve as Bactericidal and Antibiofilm Agents Targeting Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 273, 132990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeaman, M.R.; Yount, N.Y. Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Peptide Action and Resistance. Pharmacol. Rev. 2003, 55, 27–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ning, H.; Cong, Y.; Lin, H.; Wang, J. Development of Cationic Peptide Chimeric Lysins Based on Phage Lysin Lysqdvp001 and Their Antibacterial Effects against Vibrio parahaemolyticus: A Preliminary Study. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2021, 358, 109396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Ji, J.; Li, X.; Zhu, H.; Duan, X.; Hu, D.; Qian, P. A Novel Chimeric Endolysin Cly2v Shows Potential in Treating Streptococci-Induced Bovine Mastitis and Systemic Infections. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1482189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agún, S.; Fernández, L.; Rodríguez, A.; García, P. Deletion of the Amidase Domain of Endolysin LysRODI Enhances Antistaphylococcal Activity in Milk and during Fresh Cheese Production. Food Microbiol. 2022, 107, 104067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warring, S.L.; Sisson, H.M.; Randall, G.; Grimon, D.; Dams, D.; Gutiérrez, D.; Fellner, M.; Fagerlund, R.D.; Briers, Y.; Jackson, S.A.; et al. Engineering an Antimicrobial Chimeric Endolysin That Targets the Phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae Pv. actinidiae. J. Biol. Chem. 2025, 301, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, B.; Kong, M.; Lee, Y.; Ryu, S. Development of a Novel Chimeric Endolysin, Lys109 with Enhanced Lytic Activity Against Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 615887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, D.; Rodríguez-Rubio, L.; Ruas-Madiedo, P.; Fernández, L.; Campelo, A.B.; Briers, Y.; Nielsen, M.W.; Pedersen, K.; Lavigne, R.; García, P.; et al. Design and Selection of Engineered Lytic Proteins with Staphylococcus aureus Decolonizing Activity. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 723834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fokine, A.; Miroshnikov, K.A.; Shneider, M.M.; Mesyanzhinov, V.V.; Rossmann, M.G. Structure of the Bacteriophage φKZ Lytic Transglycosylase Gp144. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 7242–7250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Love, M.J.; Coombes, D.; Ismail, S.; Billington, C.; Dobson, R.C.J. The Structure and Function of Modular Escherichia coli O157:H7 Bacteriophage FTBEc1 Endolysin, LysT84: Defining a New Endolysin Catalytic Subfamily. Biochem. J. 2022, 479, 207–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.-E.; Wei, H. Novel Chimeric Lysin with High-Level Antimicrobial Activity against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus In Vitro and In Vivo. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2014, 58, 536–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, J.; Schmelcher, M.; Harty, W.J.; Foster-Frey, J.; Donovan, D.M. Chimeric Ply187 Endolysin Kills Staphylococcus aureus More Effectively than the Parental Enzyme. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2013, 342, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumrall, E.T.; Röhrig, C.; Hupfeld, M.; Selvakumar, L.; Du, J.; Dunne, M.; Schmelcher, M.; Shen, Y.; Loessner, M.J. Glycotyping and Specific Separation of Listeria monocytogenes with a Novel Bacteriophage Protein Tool Kit. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e00612-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Yu, J.; Wei, H. A Novel Chimeric Lysin with Robust Antibacterial Activity against Planktonic and Biofilm Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 40182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duyvejonck, L.; Gerstmans, H.; Stock, M.; Grimon, D.; Lavigne, R.; Briers, Y. Rapid and High-Throughput Evaluation of Diverse Configurations of Engineered Lysins Using the VersaTile Technique. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, M.J.; Garefalaki, V.; Spoerl, R.; Narbad, A.; Meijers, R. Structure-Based Modification of a Clostridium Difficile-Targeting Endolysin Affects Activity and Host Range. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 5477–5486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oechslin, F.; Menzi, C.; Moreillon, P.; Resch, G. The Multidomain Architecture of a Bacteriophage Endolysin Enables Intramolecular Synergism and Regulation of Bacterial Lysis. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 296, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, D.; Schuch, R.; Chahales, P.; Zhu, S.; Fischetti, V.A. PlyC: A Multimeric Bacteriophage Lysin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10765–10770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, M.; O’Flynn, G.; Garry, J.; Cooney, J.; Coffey, A.; Fitzgerald, G.F.; Ross, R.P.; McAuliffe, O. Phage Lysin LysK Can Be Truncated to Its CHAP Domain and Retain Lytic Activity against Live Antibiotic-Resistant Staphylococci. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2009, 75, 872–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doehn, J.M.; Fischer, K.; Reppe, K.; Gutbier, B.; Tschernig, T.; Hocke, A.C.; Fischetti, V.A.; Loffler, J.; Suttorp, N.; Hippenstiel, S.; et al. Delivery of the Endolysin Cpl-1 by Inhalation Rescues Mice with Fatal Pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2013, 68, 2111–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Liang, J.; Hu, L.; Gong, P.; Zhang, L.; Cai, R.; Zhang, H.; Ge, J.; et al. Endolysin LysEF-P10 Shows Potential as an Alternative Treatment Strategy for Multidrug-Resistant Enterococcus faecalis Infections. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, A.; Oh, J.T.; Sauve, K.; Bradford, P.A.; Cassino, C.; Schuch, R. Antimicrobial Activity of Exebacase (Lysin CF-301) against the Most Common Causes of Infective Endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e01078-19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, H.; Yu, J.; Wei, H. Molecular Dissection of Phage Lysin PlySs2: Integrity of the Catalytic and Cell Wall Binding Domains Is Essential for Its Broad Lytic Activity. Virol. Sin. 2015, 30, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, J.L.; Sharma, M.; Gulati, K.; Kairamkonda, M.; Kumar, D.; Poluri, K.M. Engineering of a T7 Bacteriophage Endolysin Variant with Enhanced Amidase Activity. Biochemistry 2023, 62, 330–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, L.Y.; Yang, C.; Perego, M.; Osterman, A.; Liddington, R. Role of Net Charge on Catalytic Domain and Influence of Cell Wall Binding Domain on Bactericidal Activity, Specificity, and Host Range of Phage Lysins. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 34391–34403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, X.; Nelson, D.C. Contributions of Net Charge on the PlyC Endolysin CHAP Domain. Antibiotics 2019, 8, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plotka, M.; Kaczorowska, A.-K.; Morzywolek, A.; Makowska, J.; Kozlowski, L.P.; Thorisdottir, A.; Skírnisdottir, S.; Hjörleifsdottir, S.; Fridjonsson, O.H.; Hreggvidsson, G.O.; et al. Biochemical Characterization and Validation of a Catalytic Site of a Highly Thermostable Ts2631 Endolysin from the Thermus scotoductus Phage vB_Tsc2631. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0137374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kairamkonda, M.; Gulati, K.; Jose, S.; Ghate, M.; Saxena, H.; Sharma, M.; Poluri, K.M. Assessing the Role of Zinc in the Structure-Stability-Activity Paradigm of Bacteriophage T7 Endolysin. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 341, 126466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Feng, Y.; Feng, X.; Sun, C.; Lei, L.; Ding, W.; Niu, F.; Jiao, L.; Yang, M.; Li, Y.; et al. Structural and Biochemical Characterization Reveals LysGH15 as an Unprecedented “EF-Hand-Like” Calcium-Binding Phage Lysin. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, H.; Kobayashi, S.; Takahashi, I.; Kamitori, S.; Tamai, E. Biochemical Characterizations of the Putative Amidase Endolysin Ecd18980 Catalytic Domain from Clostridioides difficile. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2023, 46, 1625–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Yu, J.; Wei, H. Degradation of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms Using a Chimeric Lysin. Biofouling 2014, 30, 667–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichenseher, F.; Herpers, B.L.; Badoux, P.; Leyva-Castillo, J.M.; Geha, R.S.; Van Der Zwart, M.; McKellar, J.; Janssen, F.; De Rooij, B.; Selvakumar, L.; et al. Linker-Improved Chimeric Endolysin Selectively Kills Staphylococcus aureus In Vitro, on Reconstituted Human Epidermis, and in a Murine Model of Skin Infection. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2022, 66, e02273-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idelevich, E.A.; Von Eiff, C.; Friedrich, A.W.; Iannelli, D.; Xia, G.; Peters, G.; Peschel, A.; Wanninger, I.; Becker, K. In Vitro Activity against Staphylococcus aureus of a Novel Antimicrobial Agent, PRF-119, a Recombinant Chimeric Bacteriophage Endolysin. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 4416–4419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Rubio, L.; Martínez, B.; Rodríguez, A.; Donovan, D.M.; Götz, F.; García, P. The Phage Lytic Proteins from the Staphylococcus aureus Bacteriophage vB_SauS-phiIPLA88 Display Multiple Active Catalytic Domains and Do Not Trigger Staphylococcal Resistance. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e64671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.C.; Foster-Frey, J.; Stodola, A.J.; Anacker, D.; Donovan, D.M. Differentially Conserved Staphylococcal SH3b_5 Cell Wall Binding Domains Confer Increased Staphylolytic and Streptolytic Activity to a Streptococcal Prophage Endolysin Domain. Gene 2009, 443, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmelcher, M.; Shen, Y.; Nelson, D.C.; Eugster, M.R.; Eichenseher, F.; Hanke, D.C.; Loessner, M.J.; Dong, S.; Pritchard, D.G.; Lee, J.C.; et al. Evolutionarily Distinct Bacteriophage Endolysins Featuring Conserved Peptidoglycan Cleavage Sites Protect Mice from MRSA Infection. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1453–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, S.C.; Dong, S.; Baker, J.R.; Foster-Frey, J.; Pritchard, D.G.; Donovan, D.M. LysK CHAP Endopeptidase Domain Is Required for Lysis of Live Staphylococcal Cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009, 294, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Díez-Martínez, R.; De Paz, H.D.; García-Fernández, E.; Bustamante, N.; Euler, C.W.; Fischetti, V.A.; Menendez, M.; García, P. A Novel Chimeric Phage Lysin with High in Vitro and in Vivo Bactericidal Activity against Streptococcus pneumoniae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2015, 70, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, S.; Buckle, A.M.; Mitchell, M.S.; Hoopes, J.T.; Gallagher, D.T.; Heselpoth, R.D.; Shen, Y.; Reboul, C.F.; Law, R.H.P.; Fischetti, V.A.; et al. X-Ray Crystal Structure of the Streptococcal Specific Phage Lysin PlyC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 12752–12757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wei, X.; Wang, Z.; Huang, X.; Li, M.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, K.; Hu, Q.; Peng, H.; Shang, W.; et al. LysSYL: A Broad-Spectrum Phage Endolysin Targeting Staphylococcus Species and Eradicating S. aureus Biofilms. Microb. Cell Fact. 2024, 23, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ning, H.; Lin, H.; Wang, J.; He, X.; Lv, X.; Ju, L. Characterizations of the Endolysin Lys84 and Its Domains from Phage Qdsa002 with High Activities against Staphylococcus aureus and Its Biofilms. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2021, 148, 109809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, L.; Wu, B.; Zhou, B.; Tan, P.; Kang, Y.; Yan, Y.; Zong, Y.; Li, S.; Liu, Z.; Hong, L. AI-Enabled Alkaline-Resistant Evolution of Protein to Apply in Mass Production. eLife 2025, 13, RP102788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerstmans, H.; Criel, B.; Briers, Y. Synthetic Biology of Modular Endolysins. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 624–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgakis, N.; Premetis, G.E.; Pantiora, P.; Varotsou, C.; Bodourian, C.S.; Labrou, N.E. The Impact of Metagenomic Analysis on the Discovery of Novel Endolysins. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2025, 109, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Approach | Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Optimal endolysin-peptide linker length | LysPA26 | [68] |

| In silico design pipeline | P362, P372 | [69] |

| Endolysin-peptide combinations | Lys | [70] |

| Composite library screening | Dutarlysin-1,2,3 | [71] |

| Approach | Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Large scale library screen | ClyC | [52] |

| Domain-swapping to treat bovine mastitis | Cly2v | [74] |

| Domain deletion | LysRODI | [75] |

| Domain-swapping bacteriophage proteins | ELP-E10 | [76] |

| Strategy | Approach | Key Examples | Main Modifications | Functional Outcome | Key Insight | Citations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic-site engineering | Target conserved peptidoglycan bonds | PlyC, LysK, Cpl-1, LysEF-P10, Exebacase, PlySs2 | Selection/optimization of catalytic domains (CHAP, amidase, lysozyme) | Increased specificity and activity against MDR strains and biofilms | Catalytic-domain choice strongly dictates spectrum, efficiency and resistance profile | [1,2,3,4,5,6] |

| Dual catalytic-domains | Combine two domains | Cpl-711, PlySK1249, PlyC, LysSYL, Lys84, Lys109 | CHAP/muramidase/amidase | Higher potency, lower resistance, biofilm disruption | Multiple bond cleavage improves robustness | [1,15,19,22,23,24,25] |

| Multi-catalytic domains | Combine multiple domains | Triple-acting lysins | Triple domain architectures | Active against drug-resistant/intracellular bacteria | Multi-domains overcome physiological barriers and persistence | [26] |

| Point mutagenesis | Single-residue substitutions | CD27L (L98 → W), T7 amidase (H37A), core variant (E88M) LysF1 | Amino-acid changes in active, gating sites, or core. | Altered species specificity; increased activity and stability | Small mutations can tune specificity and activity | [7,8,9] |

| Charge engineering | Alter net charge of catalytic domain | Zn2+-dependent amidase; CHAP of PlyC | Electrostatic surface modification | Mixed or no improvement; sometimes reduced activity | Charge affects host range but is not reliable as a sole strategy | [10,11] |

| Metal-binding pocket engineering | Modify Zn2+/Ca2+ binding sites | Multiple Zn2+/Ca2+-dependent lysins | Mutations in metal coordination sites | Loss or reduction in activity | Metal-binding sites are poor targets compared to catalytic residues | [4,12,13,14] |

| Domain fusion | Swap/combine catalytic/binding domains | PlySK1249, LysK, Ecd18980CD | Rational fusion/truncation of EADs and CBDs | Enhanced lysis through domain synergy | Noncatalytic domains can enhance catalytic performance via positioning/synergy | [2,15,16] |

| Catalytic chimeras | Replace native EADs | Ply187AN-KSH3b, ClyH, Lys109 | EAD replacement + CBD/domain fusion | Broader range (incl. MRSA), stronger activity | Domain swapping yields higher potency than parental enzymes | [17,18,19] |

| Endolysin–bacteriocin hybrids | Endolysin- bacteriocin domain fusions | SA.100, XZ.700, HY-133 | Lysostaphin catalytic domain + SH3b domain + optimized linkers + endolysin catalytic domain | Increased activity and expanded range (incl. MRSA) | Linker and domain origin critically influence performance | [20,21] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aitken, M.; Abeysekera, G.; Billington, C.; Dobson, R.C.J. Recent Advances in Endolysin Engineering. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121285

Aitken M, Abeysekera G, Billington C, Dobson RCJ. Recent Advances in Endolysin Engineering. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121285

Chicago/Turabian StyleAitken, Mackenzie, Gayan Abeysekera, Craig Billington, and Renwick C. J. Dobson. 2025. "Recent Advances in Endolysin Engineering" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121285

APA StyleAitken, M., Abeysekera, G., Billington, C., & Dobson, R. C. J. (2025). Recent Advances in Endolysin Engineering. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121285