Efficacy of Dual-Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement Against Multi-Drug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis in a Galleria mellonella Model of Periprosthetic Joint Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

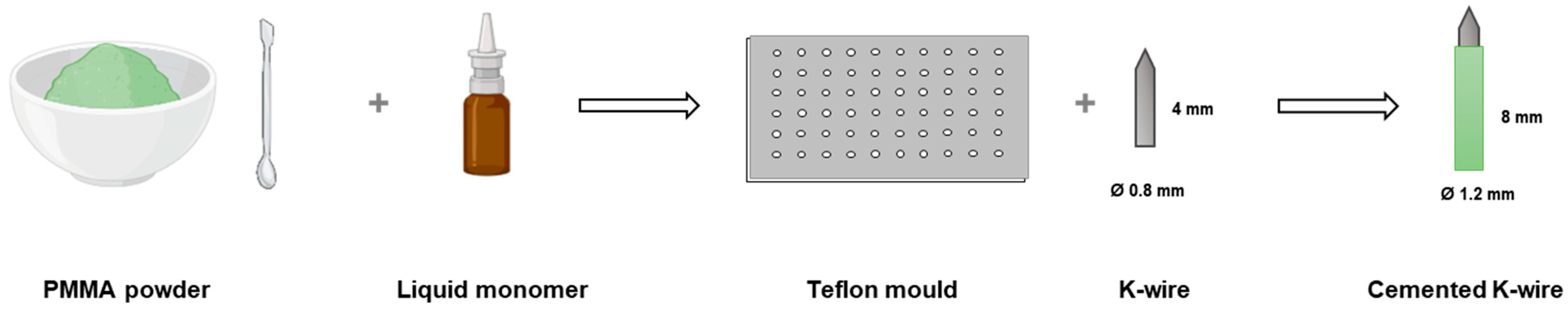

2.1. S. aureus and E. faecalis Exhibit Resistance to Gentamicin and Clindamycin

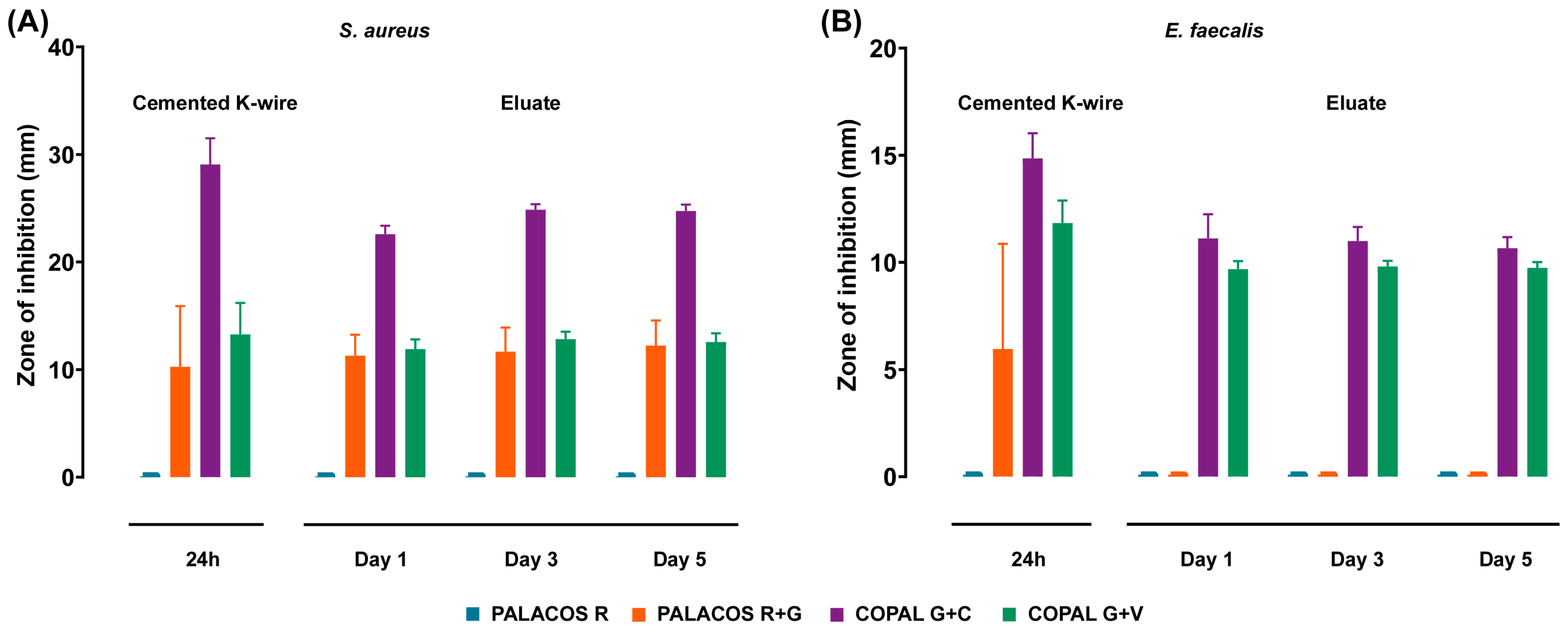

2.2. Cemented K-Wires Suppress Bacterial Growth In Vitro

2.2.1. Antibiotic-Loaded Cemented K-Wires Inhibit S. aureus and E. faecalis Despite Resistance

2.2.2. Antibiotic Eluates Maintain Antimicrobial Activity over Time

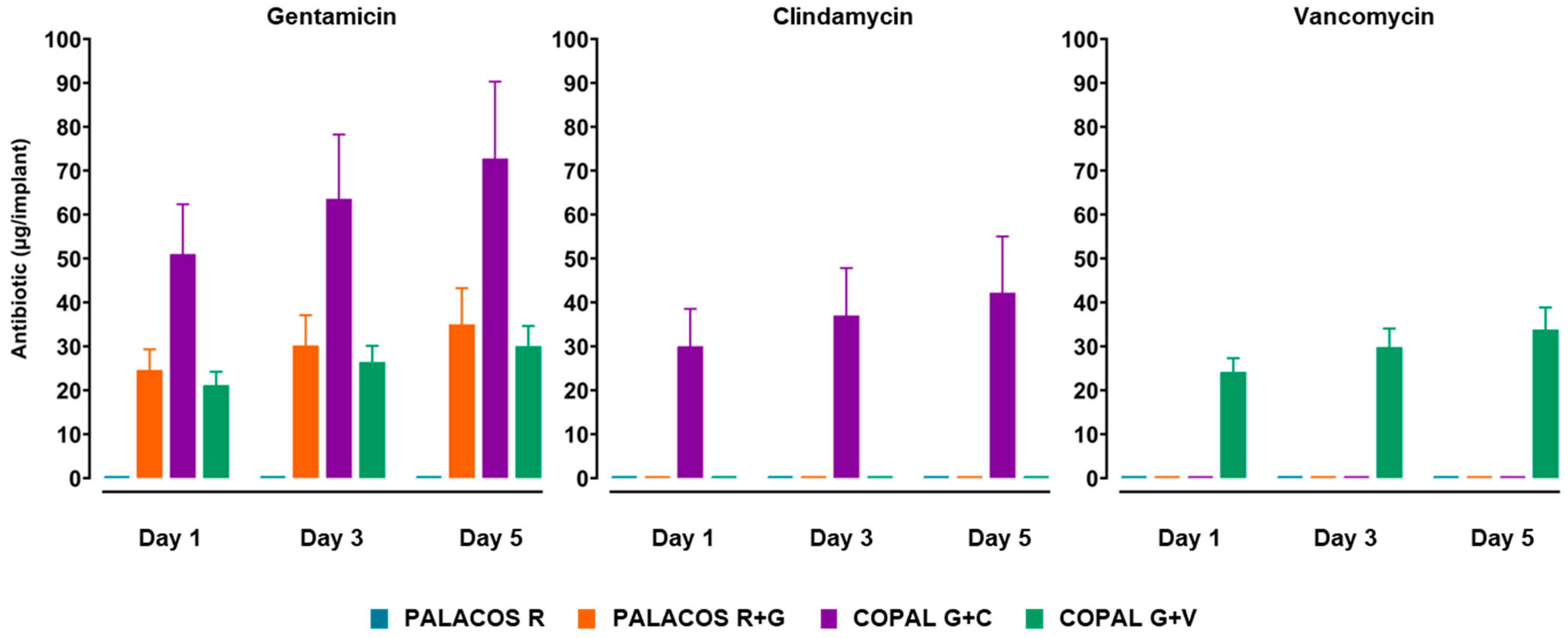

2.3. Antibiotic Release from Cemented K-Wires Shows a Burst on Day 1 Followed by a Slower Sustained Phase

2.4. Cemented K-Wires Exhibit Antibiofilm Activity In Vitro

2.4.1. Dual-Antibiotic-Loaded K-Wires Effectively Disrupt S. aureus Biofilms

2.4.2. Vancomycin-Loaded Cemented K-Wires Reduce E. faecalis Biofilms

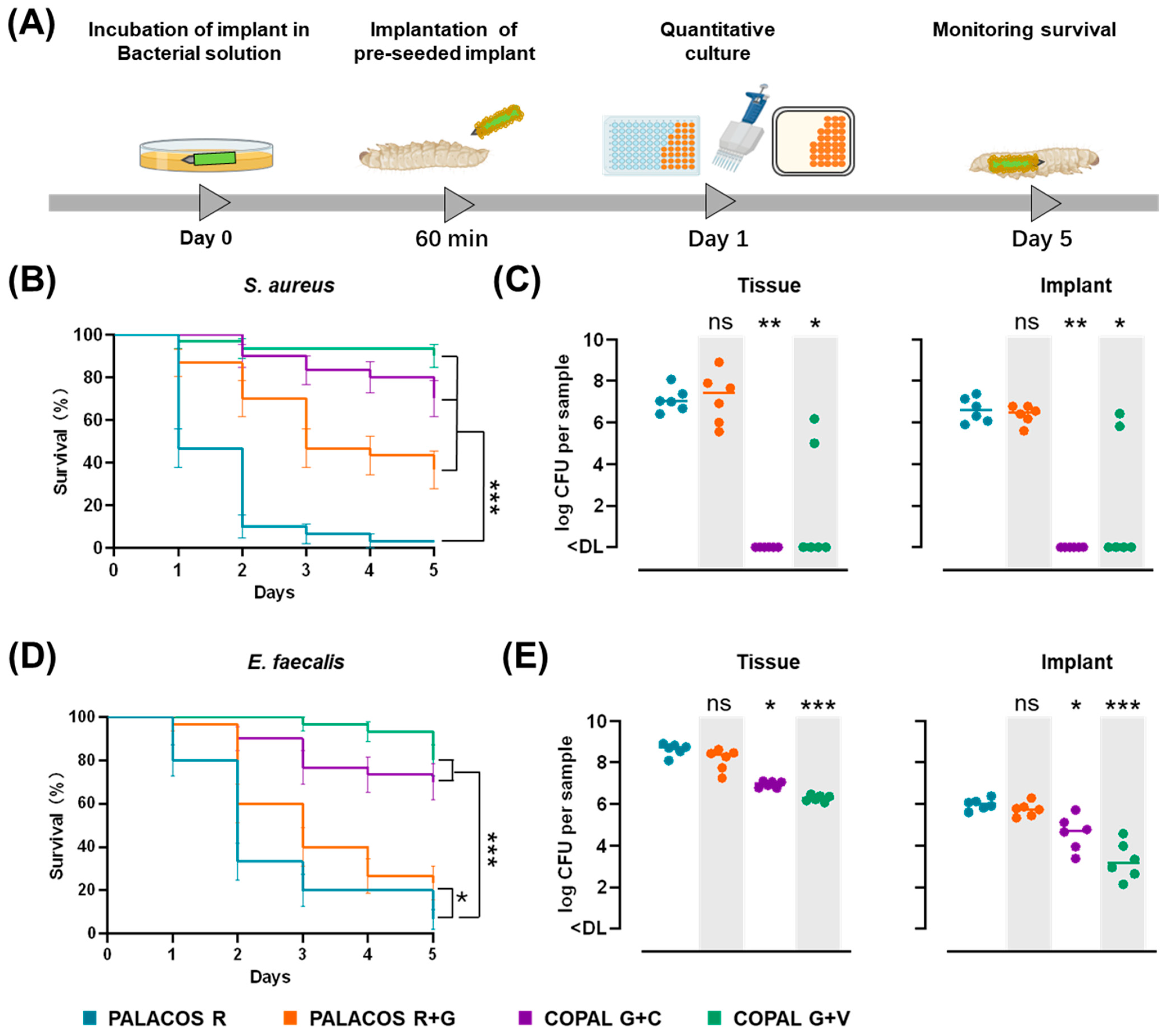

2.5. Antibiotic-Loaded Cemented K-Wires Prevent Biofilm Infections In Vivo

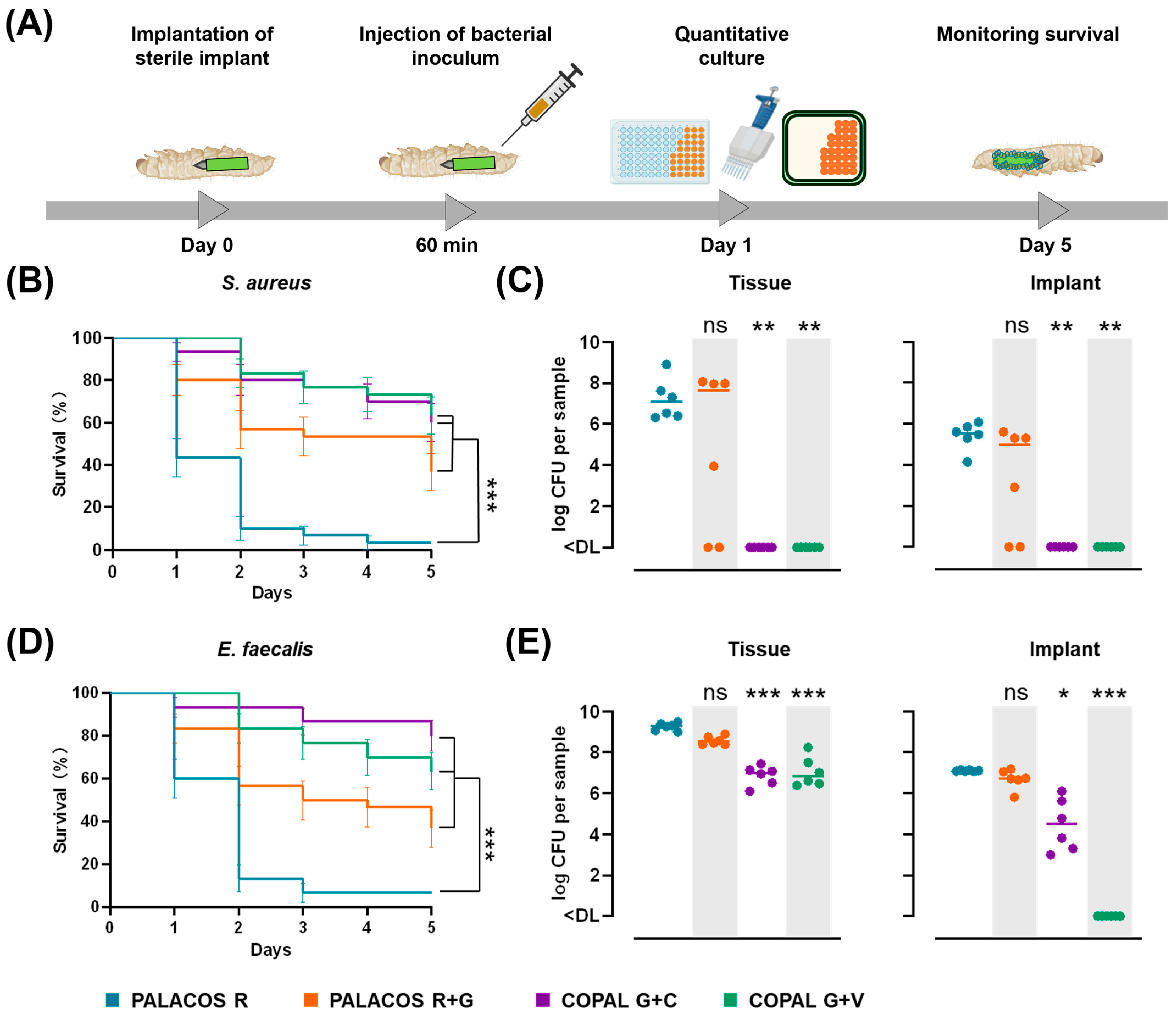

2.5.1. Dual-Antibiotic-Loaded Cemented K-Wires Protect Against Biofilm-Associated Pathogenicity

2.5.2. Dual-Antibiotic-Loaded Cemented K-Wires Reduce Bacterial Load on Implants and in Tissue

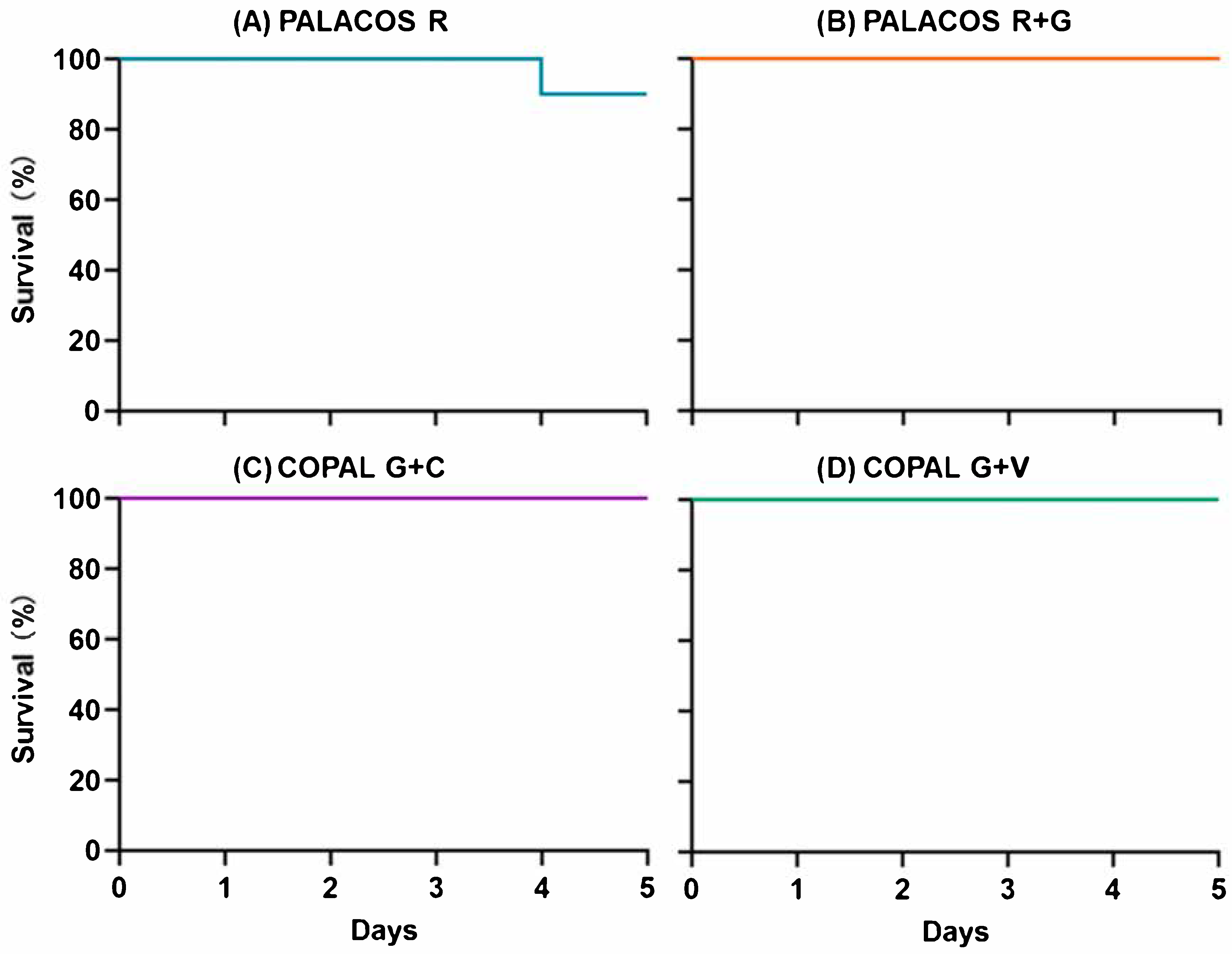

2.6. Antibiotic-Loaded K-Wires Prevent Haematogenous Implant Infection in G. mellonella

2.6.1. Antibiotic-Loaded Cemented K-Wires Increase Survival in S. aureus and E. faecalis Infected Larvae

2.6.2. Dual-Antibiotic-Loaded Cemented K-Wires Eliminate Bacteria from Implants and Surrounding Tissue

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Bacterial Cultures

4.2. Antibiotics and Bone Cement Formulations

4.3. Antimicrobial Activity of Antibiotics in Solution (MIC/MBC)

4.4. Preparation of Cemented Implants

4.5. Release Kinetics of Antibiotics from Cemented K-Wires

4.6. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of Cemented K-Wires

4.6.1. Agar Diffusion Assay

4.6.2. Antibiofilm Assay of Cemented K-Wires

4.7. G. mellonella Implant Infection Models

4.7.1. Animals

4.7.2. Biofilm Implant Infection Model

4.7.3. Haematogenous Implant Infection Model

4.7.4. Quantitative Culture

4.8. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Shichman, I.; Askew, N.; Habibi, A.; Nherera, L.; Macaulay, W.; Seyler, T.; Schwarzkopf, R. Projections and Epidemiology of Revision Hip and Knee Arthroplasty in the United States to 2040–2060. Arthroplast. Today 2023, 21, 101152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanzinga, T.; Tanzi, G.; Iacono, F.; Ferrari, M.C.; Marcacci, M. Periprosthetic Knee Infection: Two Stage Revision Surgery. Acta Biomed. 2017, 88, 114–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alt, V.; Szymski, D.; Rupp, M.; Fontalis, A.; Vaznaisiene, D.; Marais, L.C.; Wagner, C.; Walter, N. The Health-Economic Burden of Hip and Knee Periprosthetic Joint Infections in Europe. Bone Jt. Open 2025, 6, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flurin, L.; Greenwood-Quaintance, K.E.; Patel, R. Microbiology of Polymicrobial Prosthetic Joint Infection. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 94, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, D.B.G.; Patel, R.; Abdel, M.P.; Berbari, E.F.; Tande, A.J. Microbiology of Hip and Knee Periprosthetic Joint Infections: A Database Study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 255–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arciola, C.R.; Campoccia, D.; Montanaro, L. Implant Infections: Adhesion, Biofilm Formation and Immune Evasion. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 397–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakhani, A.; Jindal, K.; Khatri, K. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) in Orthopaedic Surgeries: A Complex Issue and Global Threat. J. Orthop. Reports 2024, 4, 100466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Fang, X.; Shi, T.; Cai, Y.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Lin, J.; Li, W. Cemented Prosthesis as Spacer for Two-Stage Revision of Infected Hip Prostheses: A Similar Infection Remission Rate and a Lower Complication Rate. Bone Jt. Res. 2020, 9, 484–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Gao, Z.; Shan, T.; Asilebieke, A.; Guo, R.; Kan, Y.; Li, C.; Xu, Y.; Chu, J. A Review on the Promising Antibacterial Agents in Bone Cement–From Past to Current Insights. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2024, 19, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berberich, C.E.; Josse, J.; Laurent, F.; Ferry, T. Dual Antibiotic Loaded Bone Cement in Patients at High Infection Risks in Arthroplasty: Rationale of Use for Prophylaxis and Scientific Evidence. World J. Orthop. 2021, 12, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, E.A.; Muharib, R.; Alruwaili, K.; Abdulhamid, F.; Alanazi, A.; Alruwaili, A.; Talal, M.; Alruwaili, A. Efficacy and Safety of Dual vs Single Antibiotic-Loaded Cement in Bone Fracture Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e75208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cara, A.; Ferry, T.; Laurent, F.; Josse, J. Prophylactic Antibiofilm Activity of Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cements against Gram-Negative Bacteria. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.; Cai, X.-Z.; Shi, M.-M.; Ying, Z.-M.; Hu, B.; Zhou, C.-H.; Wang, W.; Shi, Z.-L.; Yan, S.-G. In Vitro and In Vivo Evaluation of Vancomycin-Loaded PMMA Cement in Combination with Ultrasound and Microbubbles-Mediated Ultrasound. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiani, A.K.; Pheby, D.; Henehan, G.; Brown, R.; Sieving, P.; Sykora, P.; Marks, R.; Falsini, B.; Capodicasa, N.; Miertus, S.; et al. Ethical Considerations Regarding Animal Experimentation. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2022, 63, E255–E266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.J.; Clutton, R.E.; Lilley, E.; Hansen, K.E.A.; Brattelid, T. PREPARE: Guidelines for Planning Animal Research and Testing. Lab. Anim. 2018, 52, 135–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson-Sanders, S.E. Invertebrate Models for Biomedical Research, Testing, and Education. ILAR J. 2011, 52, 126–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavis-Bloom, J.; Muhammed, M.; Mylonakis, E. Of Model Hosts and Man: Using Caenorhabditis Elegans, Drosophila Melanogaster and Galleria Mellonella as Model Hosts for Infectious Disease Research. In Recent Advances on Model Hosts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Mannala, G.K.; Rupp, M.; Alagboso, F.; Kerschbaum, M.; Pfeifer, C.; Sommer, U.; Kampschulte, M.; Domann, E.; Alt, V. Galleria Mellonella as an Alternative in Vivo Model to Study Bacterial Biofilms on Stainless Steel and Titanium Implants. ALTEX 2021, 38, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Mannala, G.K.; Youf, R.; Rupp, M.; Alt, V.; Riool, M. Development of a Galleria Mellonella Infection Model to Evaluate the Efficacy of Antibiotic-Loaded Polymethyl Methacrylate (PMMA) Bone Cement. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büssemaker, H.; Meinshausen, A.-K.; Bui, V.D.; Döring, J.; Voropai, V.; Buchholz, A.; Mueller, A.J.; Harnisch, K.; Martin, A.; Berger, T.; et al. Silver-Integrated EDM Processing of TiAl6V4 Implant Material Has Antibacterial Capacity While Optimizing Osseointegration. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 31, 497–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 13.0. 2023. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Blersch, B.P.; Sax, F.H.; Mederake, M.; Benda, S.; Schuster, P.; Fink, B. Effect of Multiantibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement on the Treatment of Periprosthetic Joint Infections of Hip and Knee Arthroplasties—A Single-Center Retrospective Study. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sprowson, A.P.; Jensen, C.; Chambers, S.; Parsons, N.R.; Aradhyula, N.M.; Carluke, I.; Inman, D.; Reed, M.R. The Use of High-Dose Dual-Impregnated Antibiotic-Laden Cement with Hemiarthroplasty for the Treatment of a Fracture of the Hip the Fractured Hip Infection Trial. Bone Jt. J. 2016, 98-B, 1534–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fink, B.; Tetsworth, K.D. Antibiotic Elution from Cement Spacers and Its Influencing Factors. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, J.; Bewersdorf, T.N.; Sommer, U.; Lingner, T.; Findeisen, S.; Schamberger, C.; Schmidmaier, G.; Großner, T. Impact of Antibiotic-Loaded PMMA Spacers on the Osteogenic Potential of HMSCs. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tseng, T.-H.; Chang, C.-H.; Chen, C.-L.; Chiang, H.; Wang, J.-H.; Young, T.-H. Enhanced Antibiotic Release and Biocompatibility with Simultaneous Addition of N-Acetylcysteine and Vancomycin to Bone Cement: A Potential Replacement for High-Dose Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2025, 20, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ensing, G.T.; van Horn, J.R.; van der Mei, H.C.; Busscher, H.J.; Neut, D. Copal Bone Cement Is More Effective in Preventing Biofilm Formation than Palacos R-G. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2008, 466, 1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metsemakers, W.J.; Emanuel, N.; Cohen, O.; Reichart, M.; Potapova, I.; Schmid, T.; Segal, D.; Riool, M.; Kwakman, P.H.S.; De Boer, L.; et al. A Doxycycline-Loaded Polymer-Lipid Encapsulation Matrix Coating for the Prevention of Implant-Related Osteomyelitis Due to Doxycycline-Resistant Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus. J. Control. Release 2015, 209, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drexler, M.; Dwyer, T.; Kuzyk, P.R.T.; Kosashvilli, Y.; Abolghasemian, M.; Regev, G.J.; Kadar, A.; Rutenberg, T.F.; Backstein, D. The Results of Two-Stage Revision TKA Using Ceftazidime–Vancomycin-Impregnated Cement Articulating Spacers in Tsukayama Type II Periprosthetic Joint Infections. Knee Surg. Sport Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2016, 24, 3122–3130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Ruiz, P.; Matas-Diez, J.A.; Villanueva-Martínez, M.; Santos-Vaquinha Blanco, A.D.; Vaquero, J. Is Dual Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement More Effective and Cost-Efficient Than a Single Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement to Reduce the Risk of Prosthetic Joint Infection in Aseptic Revision Knee Arthroplasty? J. Arthroplast. 2020, 35, 3724–3729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.F.; Rossi, C.C.; da Silva, G.C.; Rosa, J.N.; Bazzolli, D.M.S. Galleria mellonella as an Infection Model: An in-Depth Look at Why It Works and Practical Considerations for Successful Application. Pathog. Dis. 2020, 78, ftaa056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.J.-Y.; Loh, J.M.S.; Proft, T. Galleria mellonella Infection Models for the Study of Bacterial Diseases and for Antimicrobial Drug Testing. Virulence 2016, 7, 214–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojda, I. Immunity of the Greater Wax Moth Galleria Mellonella. Insect Sci. 2017, 24, 342–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuara, G.; García-García, J.; Ibarra, B.; Parra-Ruiz, F.J.; Asúnsolo, A.; Ortega, M.A.; Vázquez-Lasa, B.; Buján, J.; San Román, J.; de la Torre, B. Estudio Experimental de La Aplicación de Un Nuevo Cemento Óseo Cargado Con Antibióticos de Amplio Espectro Para El Tratamiento de La Infección Ósea. Rev. Esp. Cir. Ortop. Traumatol. 2019, 63, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, E.J.; Oh, S.H.; Lee, I.S.; Kwon, O.S.; Lee, J.H. Antibiotic-Eluting Hydrophilized PMMA Bone Cement with Prolonged Bactericidal Effect for the Treatment of Osteomyelitis. J. Biomater. Appl. 2016, 30, 1534–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giavaresi, G.; Borsari, V.; Fini, M.; Giardino, R.; Sambri, V.; Gaibani, P.; Soffiatti, R. Preliminary Investigations on a New Gentamicin and Vancomycin-coated PMMA Nail for the Treatment of Bone and Intramedullary Infections: An Experimental Study in the Rabbit. J. Orthop. Res. 2008, 26, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerhart, T.N.; Roux, R.D.; Horowitz, G.; Miller, R.L.; Hanff, P.; Hayes, W.C. Antibiotic Release from an Experimental Biodegradable Bone Cement. J. Orthop. Res. 1988, 6, 585–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, W.R.; Arias, C.A. ESKAPE Pathogens: Antimicrobial Resistance, Epidemiology, Clinical Impact and Therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2024, 22, 598–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alt, V.; Lips, K.S.; Henkenbehrens, C.; Muhrer, D.; Cavalcanti-Garcia, M.; Sommer, U.; Thormann, U.; Szalay, G.; Heiss, C.; Pavlidis, T.; et al. A New Animal Model for Implant-Related Infected Non-Unions after Intramedullary Fixation of the Tibia in Rats with Fluorescent in Situ Hybridization of Bacteria in Bone Infection. Bone 2011, 48, 1146–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humez, M.; Domann, E.; Thormann, K.M.; Fölsch, C.; Strathausen, R.; Vogt, S.; Alt, V.; Kühn, K.-D. Daptomycin-Impregnated PMMA Cement against Vancomycin-Resistant Germs: Dosage, Handling, Elution, Mechanical Stability, and Effectiveness. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabee, M.M.S.M.; Awang, M.S.; Bustami, Y.; Hamid, Z.A.A. Gentamicin Loaded PLA Microspheres Susceptibility against Staphylococcus Aureus and Escherichia Coli by Kirby-Bauer and Micro-Dilution Methods. In AIP Conference Proceedings; American Institute of Physics Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Volume 2267, p. 020032. [Google Scholar]

- Boelens, J.J.; Dankert, J.; Murk, J.L.; Weening, J.J.; van der Poll, T.; Dingemans, K.P.; Koole, L.; Laman, J.D.; Zaat, S.A.J. Biomaterial-Associated Persistence of Staphylococcus Epidermidis in Pericatheter Macrophages. J. Infect. Dis. 2000, 181, 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; Emerson, M.; et al. Reporting Animal Research: Explanation and Elaboration for the ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0. PLOS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mannala, G.K.; Rupp, M.; Walter, N.; Youf, R.; Bärtl, S.; Riool, M.; Alt, V. Repetitive Combined Doses of Bacteriophages and Gentamicin Protect against Staphylococcus Aureus Implant-Related Infections in Galleria mellonella. Bone Jt. Res. 2024, 13, 383–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bacterial Strain | Antibiotic | MIC (µg/mL) | ECOFF 2 | Interpretation 1 | MBC (µg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus EDCC 5055 | Gentamicin | 4–8 | 2 | R | 8–16 |

| Clindamycin | 32 | 0.25 | R | 64–128 | |

| Vancomycin | 1 | 2 | S | 1 | |

| E. faecalis EUCC2 | Gentamicin | >128 | 128 | R | >128 |

| Clindamycin | >128 | - | R | >128 | |

| Vancomycin | 1–2 | 4 | S | 32 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Mannala, G.K.; Youf, R.; Humez, M.; Schewior, R.; Kühn, K.-D.; Alt, V.; Riool, M. Efficacy of Dual-Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement Against Multi-Drug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis in a Galleria mellonella Model of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1280. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121280

Zhao Y, Mannala GK, Youf R, Humez M, Schewior R, Kühn K-D, Alt V, Riool M. Efficacy of Dual-Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement Against Multi-Drug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis in a Galleria mellonella Model of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1280. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121280

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, You, Gopala Krishna Mannala, Raphaëlle Youf, Martina Humez, Ruth Schewior, Klaus-Dieter Kühn, Volker Alt, and Martijn Riool. 2025. "Efficacy of Dual-Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement Against Multi-Drug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis in a Galleria mellonella Model of Periprosthetic Joint Infection" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1280. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121280

APA StyleZhao, Y., Mannala, G. K., Youf, R., Humez, M., Schewior, R., Kühn, K.-D., Alt, V., & Riool, M. (2025). Efficacy of Dual-Antibiotic-Loaded Bone Cement Against Multi-Drug-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis in a Galleria mellonella Model of Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1280. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121280