Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Postoperative Therapy in Tooth Extractions for Patients at Risk of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ): A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Study Selection

2.2. Study Characteristics

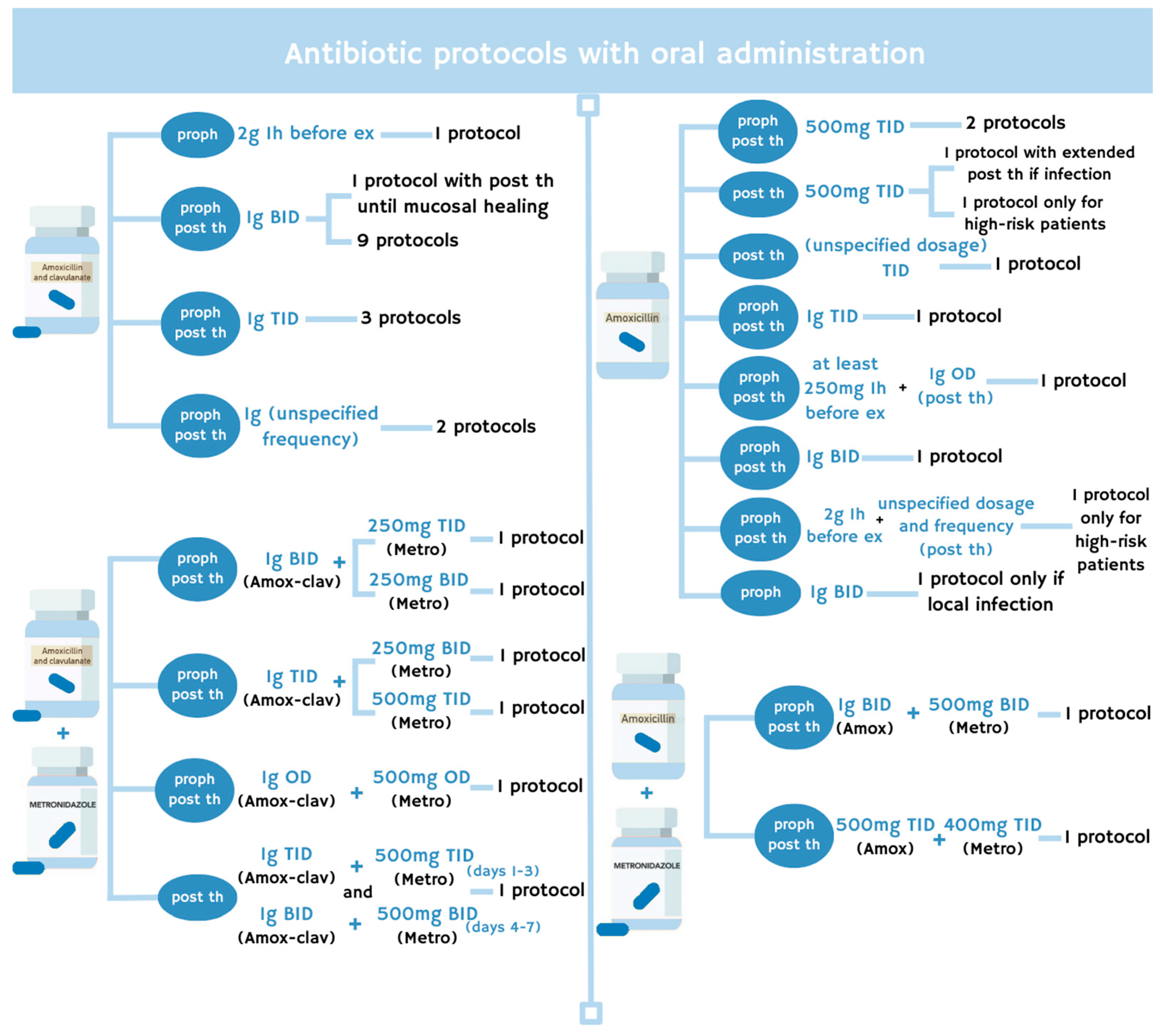

2.3. Antibiotic Protocol

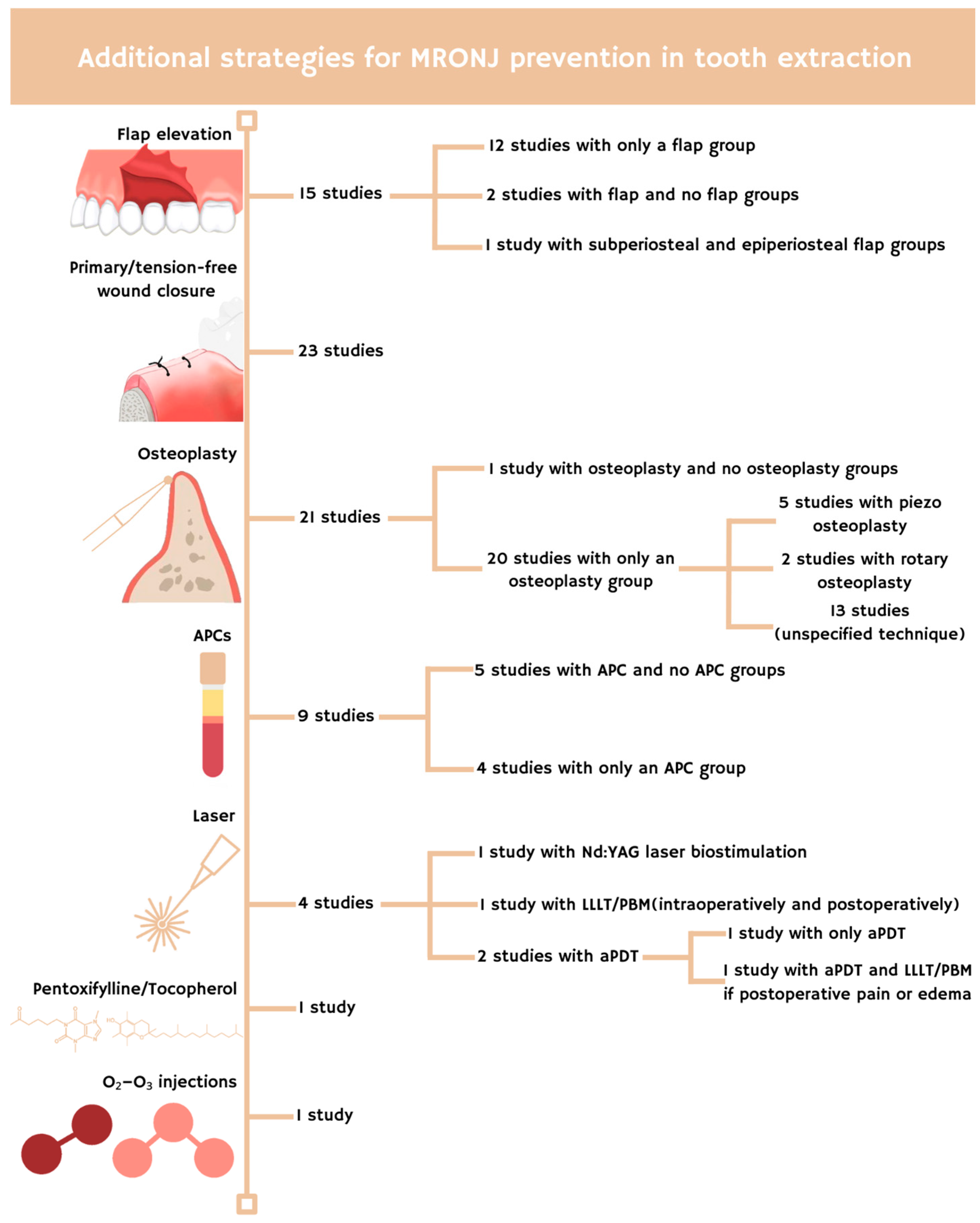

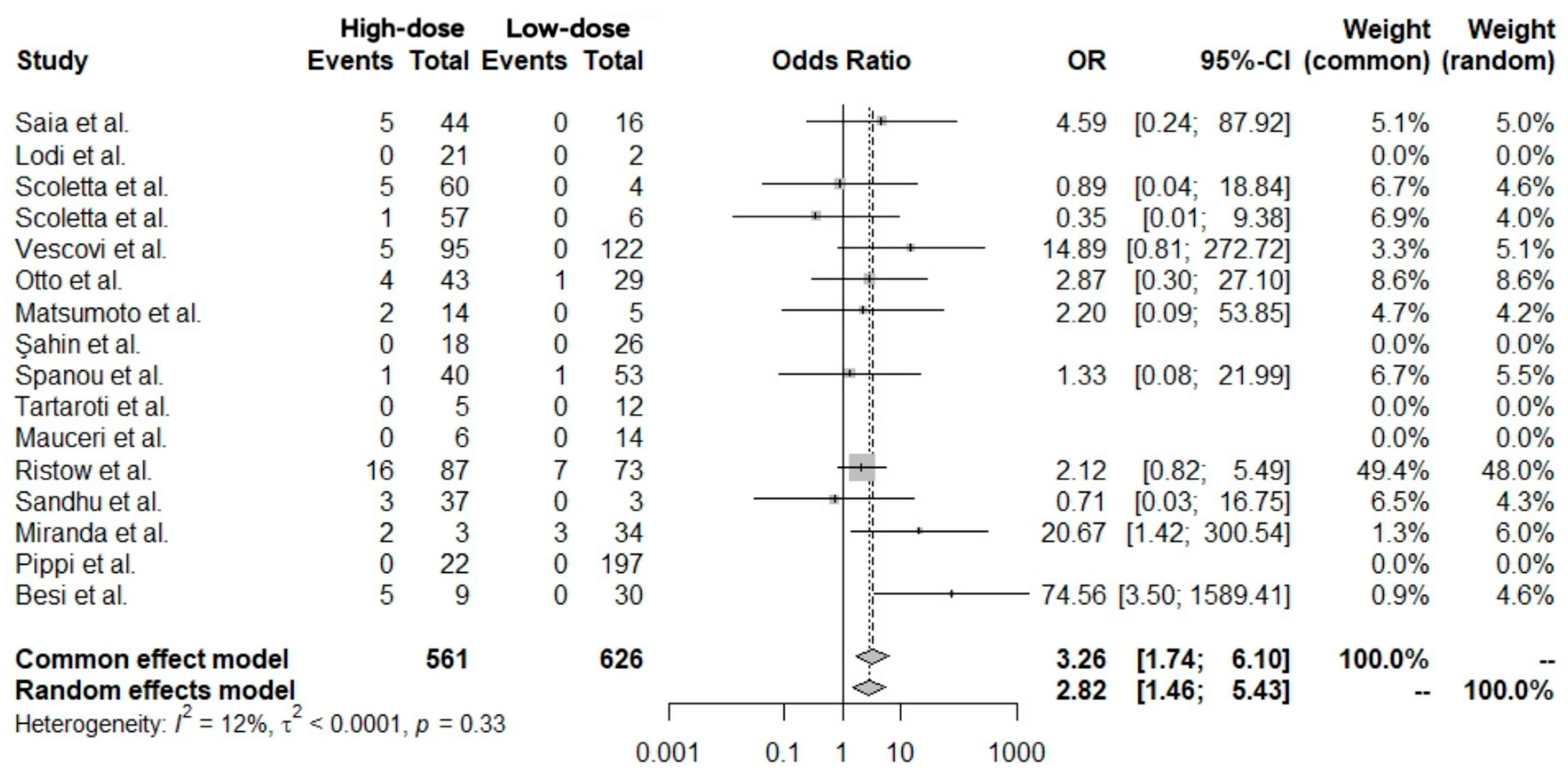

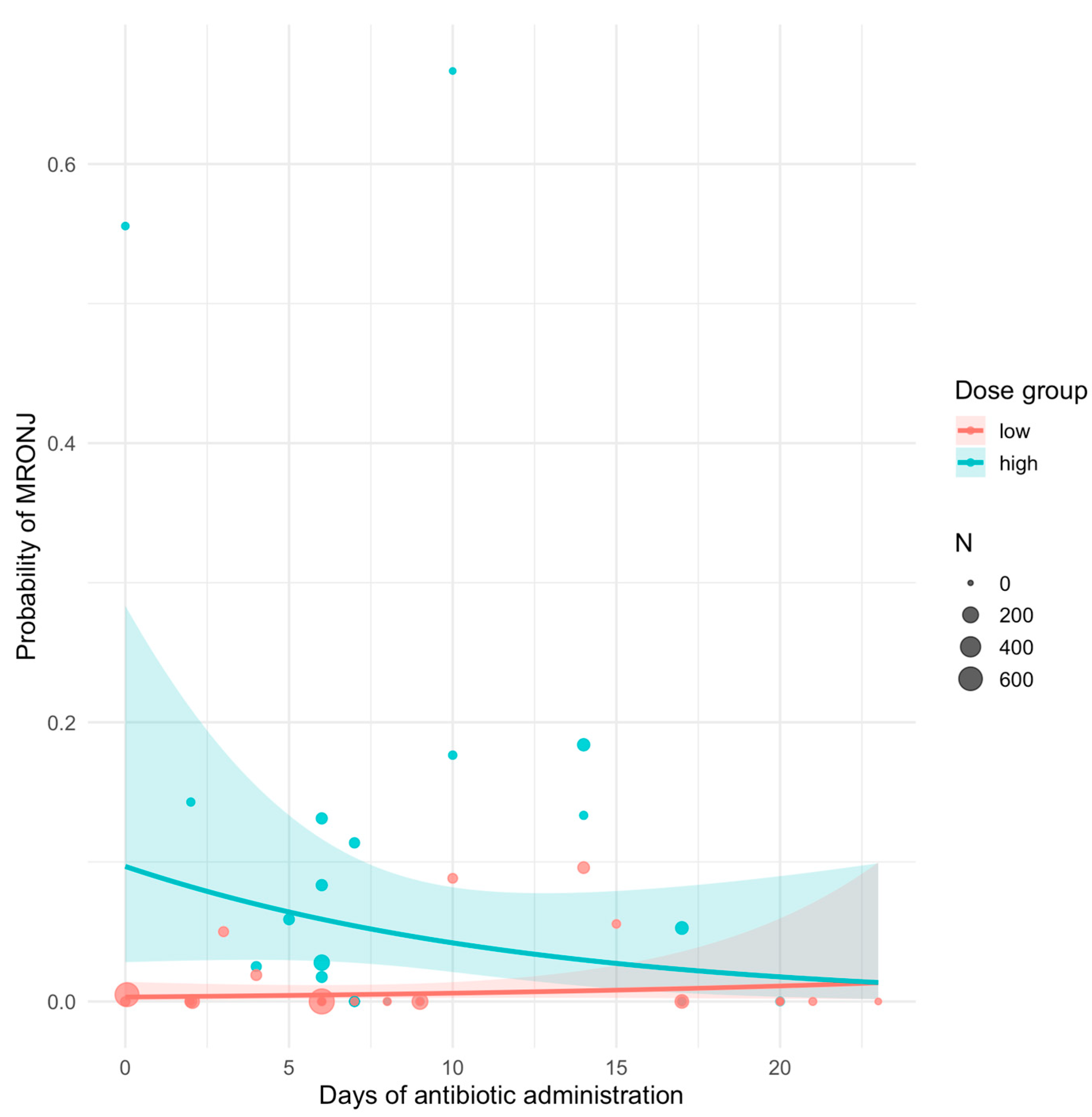

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Study Design

3.2. PICO Question

3.3. Search Strategy

3.4. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

3.5. Selection of the Studies

3.6. Data Extraction

3.7. Statistical Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BID | twice a day |

| TID | 3 times a day |

| MRONJ | Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw |

| HD | High-dose |

| LD | Low-dose |

References

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Aghaloo, T.; Carlson, E.R.; Ward, B.B.; Kademani, D. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons’ Position Paper on Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws-2022 Update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 920–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedogni, A.; Mauceri, R.; Fusco, V.; Bertoldo, F.; Bettini, G.; Di Fede, O.; Casto, A.L.; Marchetti, C.; Panzarella, V.; Saia, G.; et al. Italian position paper(SIPMO-SICMF) on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw(MRONJ). Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 3679–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennardo, F.; Buffone, C.; Muraca, D.; Antonelli, A.; Giudice, A. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw with Spontaneous Hemimaxilla Exfoliation: Report of a Case in Metastatic Renal Cancer Patient under Multidrug Therapy. Case Rep. Med. 2020, 2020, 8093293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauceri, R.; Coppini, M.; Attanasio, M.; Bedogni, A.; Bettini, G.; Fusco, V.; Giudice, A.; Graziani, F.; Marcianò, A.; Nisi, M.; et al. MRONJ in breast cancer patients under bone modifying agents for cancer treatment-induced bone loss(CTIBL): A multi-hospital-based case series. BMC Oral Health 2023, 23, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estilo, C.L.; Fornier, M.; Farooki, A.; Carlson, D.; Bohleg Huryn, J.M., 3rd. Osteonecrosis of the jaw related to bevacizumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 4037–4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.W.; Jung, Y.S.; Park, H.S.; Jung, H.D. Osteonecrosis of the jaw related to everolimus: A case report. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 51, e302–e304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleissig, Y.; Regev, E.; Lehman, H. Sunitinib related osteonecrosis of jaw: A case report. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2012, 113, e1–e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.G.; Ouanounou, A. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A narrative review of risk factors, diagnosis, and management. Front. Oral Maxillofac. Med. 2023, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A.S.E.; Glenny, A.-M. The issue with incidence: A scoping review of reported medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws(MRONJ) incidence around the globe. BMJ Public Health 2025, 3, e002009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.E. Pamidronate(Aredia) and zoledronate(Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: A growing epidemic. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwech, N.; Nilsson, J.; Gabre, P. Incidence and risk factors for medication-related osteonecrosis after tooth extraction in cancer patients-A systematic review. Clin. Exp. Dent. Res. 2023, 9, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortunato, L.; Bennardo, F.; Buffone, C.; Giudice, A. Is the application of platelet concentrates effective in the prevention and treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw? A systematic review. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2020, 48, 268–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Vito, A.; Chiarella, E.; Sovereto, J.; Bria, J.; Perrotta, I.D.; Salatino, A.; Baudi, F.; Sacco, A.; Antonelli, A.; Biamonte, F.; et al. Novel insights into the pharmacological modulation of human periodontal ligament stem cells by the amino-bisphosphonate Alendronate. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2023, 102, 151354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennardo, F.; Barone, S.; Antonelli, A.; Giudice, A. Autologous platelet concentrates as adjuvant in the surgical management of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Periodontology 2000 2025, 97, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosella, D.; Papi, P.; Giardino, R.; Cicalini, E.; Piccoli, L.; Pompa, G. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Clinical and practical guidelines. J. Int. Soc. Prev. Community Dent. 2016, 6, 97–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boff, R.C.; Salum, F.G.; Figueiredo, M.A.; Cherubini, K. Important aspects regarding the role of microorganisms in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Arch. Oral Biol. 2014, 59, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saia, G.; Blandamura, S.; Bettini, G.; Tronchet, A.; Totola, A.; Bedogni, G.; Ferronato, G.; Nocini, P.F.; Bedogni, A. Occurrence of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after surgical tooth extraction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 797–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodi, G.; Sardella, A.; Salis, A.; Demarosi, F.; Tarozzi, M.; Carrassi, A. Tooth extraction in patients taking intravenous bisphosphonates: A preventive protocol and case series. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 68, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlito, S.; Liardo, C.; Puzzo, S. Dental extractions in patient treated with intravenous bisphosphonates and risk of osteonecrosis of jaws: Presentation of a preventive protocol and case series. Minerva Stomatol. 2010, 59, 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Scoletta, M.; Arduino, P.G.; Pol, R.; Arata, V.; Silvestri, S.; Chiecchio, A.; Mozzati, M. Initial experience on the outcome of teeth extractions in intravenous bisphosphonate-treated patients: A cautionary report. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, 456–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlito, S.; Puzzo, S.; Liardo, C. Preventive protocol for tooth extractions in patients treated with zoledronate: A case series. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, e1–e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carini, F.; Saggese, V.; Porcaro, G.; Barbano, L.; Baldoni, M. Surgical protocol in patients at risk for bisphosphonate osteonecrosis of the jaws: Clinical use of serum telopetide CTX in preventive monitoring of surgical risk. Ann. Stomatol. 2012, 3, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Mozzati, M.; Arata, V.; Gallesio, G. Tooth extraction in patients on zoledronic acid therapy. Oral Oncol. 2012, 48, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozzati, M.; Arata, V.; Gallesio, G. Tooth extraction in osteoporotic patients taking oral bisphosphonates. Osteoporos. Int. 2013, 24, 1707–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scoletta, M.; Arata, V.; Arduino, P.G.; Lerda, E.; Chiecchio, A.; Gallesio, G.; Scully, C.; Mozzati, M. Tooth extractions in intravenous bisphosphonate-treated patients: A refined protocol. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 71, 994–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vescovi, P.; Meleti, M.; Merigo, E.; Manfredi, M.; Fornaini, C.; Guidotti, R.; Nammour, S. Case series of 589 tooth extractions in patients under bisphosphonates therapy. Proposal of a clinical protocol supported by Nd:YAG low-level laser therapy. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2013, 18, e680–e685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poli, P.P.; Souza, F.Á.; Ferrario, S.; Maiorana, C. Adjunctive application of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy in the prevention of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw following dentoalveolar surgery: A case series. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2019, 27, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauceri, R.; Panzarella, V.; Pizzo, G.; Oteri, G.; Cervino, G.; Mazzola, G.; Di Fede, O.; Campisi, G. Platelet-Rich Plasma(PRP) in Dental Extraction of Patients at Risk of Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws: A Two-Year Longitudinal Study. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Gianfreda, F.; Raffone, C.; Antonacci, D.; Pistilli, V.; Bollero, P. The Role of Platelet-Rich Fibrin(PRF) in the Prevention of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw(MRONJ). BioMed Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 4948139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pippi, R.; Giuliani, U.; Tenore, G.; Pietrantoni, A.; Romeo, U. What is the Risk of Developing Medication-Related Osteonecrosis in Patients with Extraction Sockets Left to Heal by Secondary Intention? A Retrospective Case Series Study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 2071–2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuozzo, A.; Iorio-Siciliano, V.; Vaia, E.; Mauriello, L.; Blasi, A.; Ramaglia, L. Incidence and risk factors associated to Medication-Related Osteo Necrosis of the Jaw(MRONJ) in patients with osteoporosis after tooth extractions. A 12-months observational cohort study. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 123, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fede, O.; La Mantia, G.; Del Gaizo, C.; Mauceri, R.; Matranga, D.; Campisi, G. Reduction of MRONJ risk after exodontia by virtue of ozone infiltration: A randomized clinical trial. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 5183–5194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodem, J.P.; Kargus, S.; Eckstein, S.; Saure, D.; Engel, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Freudlsperger, C. Incidence of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in high-risk patients undergoing surgical tooth extraction. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 510–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, S.; Tröltzsch, M.; Jambrovic, V.; Panya, S.; Probst, F.; Ristow, O.; Ehrenfeld, M.; Pautke, C. Tooth extraction in patients receiving oral or intravenous bisphosphonate administration: A trigger for BRONJ development? J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 847–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanou, A.; Nelson, K.; Ermer, M.A.; Steybe, D.; Poxleitner, P.; Voss, P.J. Primary wound closure and perioperative antibiotic therapy for prevention of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after tooth extraction. Quintessence Int. 2020, 51, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poxleitner, P.; Steybe, D.; Kroneberg, P.; Ermer, M.A.; Yalcin-Ülker, G.M.; Schmelzeisen, R.; Voss, P.J. Tooth extractions in patients under antiresorptive therapy for osteoporosis: Primary closure of the extraction socket with a mucoperiosteal flap versus application of platelet-rich fibrin for the prevention of antiresorptive agent-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2020, 48, 444–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristow, O.; Rückschloß, T.; Moratin, J.; Müller, M.; Kühle, R.; Dominik, H.; Pilz, M.; Shavlokhova, V.; Otto, S.; Hoffmann, J.; et al. Wound closure and alveoplasty after preventive tooth extractions in patients with antiresorptive intake-A randomized pilot trial. Oral Dis. 2021, 27, 532–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ristow, O.; Rückschloß, T.; Schnug, G.; Moratin, J.; Bleymehl, M.; Zittel, S.; Pilz, M.; Sekundo, C.; Mertens, C.; Engel, M.; et al. Comparison of Different Antibiotic Regimes for Preventive Tooth Extractions in Patients with Antiresorptive Intake-A Retrospective Cohort Study. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsumoto, A.; Sasaki, M.; Schmelzeisen, R.; Oyama, Y.; Mori, Y.; Voss, P.J. Primary wound closure after tooth extraction for prevention of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients under denosumab. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shudo, A.; Kishimoto, H.; Takaoka, K.; Noguchi, K. Long-term oral bisphosphonates delay healing after tooth extraction: A single institutional prospective study. Osteoporos. Int. 2018, 29, 2315–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, K.; Kaneko, T.; Kamimoto, A.; Wada, M.; Takeuchi, Y.; Furuchi, M.; Iinuma, T. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after tooth extraction in patients receiving pharmaceutical treatment for osteoporosis: A retrospective cohort study. J. Dent. Sci. 2022, 17, 1619–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tartaroti, N.C.; Marques, M.M.; Naclério-Homem, M.D.G.; Migliorati, C.A.; Zindel Deboni, M.C. Antimicrobial photodynamic and photobiomodulation adjuvant therapies for prevention and treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: Case series and long-term follow-up. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2020, 29, 101651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parise, G.K.; Costa, B.N.; Nogueira, M.L.; Sassi, L.M.; Schussel, J.L. Efficacy of fibrin-rich platelets and leukocytes(L-PRF) in tissue repair in surgical oral procedures in patients using zoledronic acid-case-control study. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 27, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magalhães, J.M.I.; da Motta Silveira, F.M.; Regueira, L.S.; de Lima ESilva, D.F.; de Andrade Veras, S.R.; de Mello, M.J.G. Pentoxifylline and tocopherol as prophylaxis for osteonecrosis of the jaw due to bone-modifying agents in patients with cancer submitted to tooth extraction: A case series. Support. Care Cancer 2023, 31, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, E.; Taylor, T.; Patel, J.; Hamid, U.; Bryant, C. The incidence of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw following tooth extraction in patients prescribed oral bisphosphonates. Br. Dent. J. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besi, E.; Pitros, P. The role of leukocyte and platelet-rich fibrin in the prevention of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, in patients requiring dental extractions: An observational study. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 28, 785–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutcheson, A.; Cheng, A.; Kunchar, R.; Stein, B.; Sambrook, P.; Goss, A. A C-terminal crosslinking telopeptide test-based protocol for patients on oral bisphosphonates requiring extraction: A prospective single-center controlled study. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 72, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Y.S.; Nanayakkara, S.; Yaacoub, A.; Cox, S.C. Prevention of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: Institutional insights from a retrospective study. Aust. Dent. J. 2025, 70, 70–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, O.; Tatar, B.; Ekmekcioğlu, C.; Aliyev, T.; Odabaşı, O. Prevention of medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw after dentoalveolar surgery: An institution’s experience. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2020, 12, e771–e776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karaca, Ç.; Topaloğlu-Yasan, G.; Adiloğlu, S.; Usman, E. The effect of drug holiday before tooth extraction on the development of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in cancer patients receiving intravenous bisphosphonates. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2023, 49, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandhu, S.; Salous, M.H.; Sankar, V.; Margalit, D.N.; Villa, A. Osteonecrosis of the jaw and dental extractions: A single-center experience. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2020, 130, 515–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesclous, P.; Cloitre, A.; Catros, S.; Devoize, L.; Louvet, B.; Châtel, C.; Foissac, F.; Roux, C. Alendronate or Zoledronic acid do not impair wound healing after tooth extraction in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Bone 2020, 137, 115412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan-a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 2016, 5, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bates, D.; Mächler, M.; Bolker, B.M.; Walker, S.C. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J. Stat. Softw. 2015, 67, 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Computing R (Version 4.4.1) R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing, R Core Team Technical Report R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024.

- Bassan Marinho Maciel, G.; Marinho Maciel, R.; Linhares Ferrazzo, K.; Cademartori Danesi, C. Etiopathogenesis of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: A review. J. Mol. Med. 2024, 102, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jelin-Uhlig, S.; Weigel, M.; Ott, B.; Imirzalioglu, C.; Howaldt, H.-P.; Böttger, S.; Hain, T. Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw and Oral Microbiome: Clinical Risk Factors, Pathophysiology and Treatment Options. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano-Kelhoffer, B.; Lorca, C.; Llanes, J.M.; Rábano, A.; del Ser, T.; Serra, A.; Gallart-Palau, X. Oral Microbiota, Its Equilibrium and Implications in the Pathophysiology of Human Diseases: A Systematic Review. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Jung, Y.S.; Park, W.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, J.Y. Can medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw be attributed to specific microorganisms through oral microbiota analyses? A preliminary study. BMC Oral Health 2024, 24, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirk, M.; Wenzel, C.; Buller, J.; Zöller, J.E.; Zinser, M.; Peters, F. Microbial diversity in infections of patients with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 2143–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akashi, M.; Kusumoto, J.; Takeda, D.; Shigeta, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Komori, T. A literature review of perioperative antibiotic administration in surgery for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 22, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poveda Roda, R.; Bagan, J.V.; Sanchis Bielsa, J.M.; Carbonell Pastor, E. Antibiotic use in dental practice. A review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2007, 12, E186–E192. [Google Scholar]

- Blatt, S.; Al-Nawas, B. A systematic review of latest evidence for antibiotic prophylaxis and therapy in oral and maxillofacial surgery. Infection 2019, 47, 519–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Gonzalez, M.V.; Cuevas-Gonzalez, J.C.; Espinosa-Cristóbal, L.F.; Donohue-Cornejo, A.; López, S.Y.R.; Acuña, R.A.S.; Calderón, A.G.M.G.; Gastelum, D.A.G. Use or abuse of antibiotics as prophylactic therapy in oral surgery: A systematic review. Medicine 2023, 102, e35011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavicić, M.J.; van Winkelhoff, A.J.; de Graaff, J. Synergistic effects between amoxicillin, metronidazole, and the hydroxymetabolite of metronidazole against Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1991, 35, 961–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestnik, M.J.; Feres, M.; Figueiredo, L.C.; Soares, G.; Teles, R.P.; Fermiano, D.; Duarte, P.M.; Faveri, M. The effects of adjunctive metronidazole plus amoxicillin in the treatment of generalized aggressive periodontitis: A 1-year double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-Pouso, A.I.; Pérez-Sayáns, M.; Chamorro-Petronacci, C.; Gándara-Vila, P.; López-Jornet, P.; Carballo, J.; García-García, A. Association between periodontitis and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2020, 49, 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isla, A.; Canut, A.; Gascón, A.R.; Labora, A.; Ardanza-Trevijano, B.; Solinís, M.Á.; Pedraz, J.L. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic evaluation of antimicrobial treatments of orofacial odontogenic infections. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2005, 44, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butranova, O.I.; Ushkalova, E.A.; Zyryanov, S.K.; Chenkurov, M.S.; Baybulatova, E.A. Pharmacokinetics of Antibacterial Agents in the Elderly: The Body of Evidence. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pea, F. Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism of antibiotics in the elderly. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 1087–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baghalipour, N.; Moztarzadeh, O.; Samar, W.; Gencur, J.; Volf, V.; Hauer, L. Comprehensive Review of Prevention and Management Strategies for Medication-related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw(MRONJ). Oral Health. Prev. Dent. 2025, 23, 403–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wróbel, K.; Sikora, M.; Chęciński, M.; Jas, M.; Chlubek, D. Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw—A Continuing Issue. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, T.; Kawakita, A.; Ueda, N.; Funahara, R.; Tachibana, A.; Kobayashi, M.; Kondou, E.; Takeda, D.; Kojima, Y.; Sato, S.; et al. A multicenter retrospective study of the risk factors associated with medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw after tooth extraction in patients receiving oral bisphosphonate therapy: Can primary wound closure and a drug holiday really prevent MRONJ? Osteoporos. Int. 2017, 28, 2465–2473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vescovi, P.; De Francesco, P.; Giovannacci, I.; Leão, J.C.; Barone, A. Piezoelectric Surgery, Er:YAG Laser Surgery and Nd:YAG Laser Photobiomodulation: A Combined Approach to Treat Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws(MRONJ). Dent. J. 2024, 12, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Słowik, Ł.; Totoń, E.; Nowak, A.; Wysocka-Słowik, A.; Okła, M.; Ślebioda, Z. Pharmacological Treatment of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ) with Pentoxifylline and Tocopherol. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reference | Study Sample (M-F) | Mean/ Median Age | Extraction (n; Site) | Low and High-Dose Treatment (n Patients) | Causes for Treatment (n Patients) | Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Tooth Extraction | Antibiotic Therapy in Tooth Extraction | Antiseptic Treatment | Additional Strategies for MRONJ Prevention in Tooth Extraction | n MRONJ/Bone Exposure Cases at Follow-Up end (Follow-Up Time; Treatment Type) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saia et al., 2010 [17] Prospective study | 60(18-42) | 65 yrs | 185 ex 103 ex mdb 82 ex max | High-dose (44; 8 patients received both Z and P) Low-dose (16) | Oncologic (44) Osteometabolic (16) | No antibiotic prophylaxis | Days 1–3: Amox-clav 1 g TID × 3 d + Metro 500 mg TID × 3 d Days 4–7: Amox-clav 1 g BID × 4 d + Metro 500 mg BID × 4 d If allergy: Linco 500 mg BID × 7 d | N/A | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty with rotary instruments, tension-free wound closure Drug holiday: 1 month after ex | 5 (6 months; HD) | |

| Lodi et al., 2010 [18] Prospective study | 23 (18-42) | 68.2 yrs | 38 ex Interventions: 23 mdb 5 max 2 both | High-dose (21) Low-dose (2) | Oncologic (21) Osteometabolic (2) | Amox-clav 1 g TID × 3 d | Amox-clav 1 g TID × 17 d | Since ex decision: 0.2% CHX rinse OD Postop: 1% CHX gel TID × 14 d | Mucoperiosteal flap, primary wound closure | 0 (mean: 229.5 d, range: 14–965 d) | |

| Ferlito et al., 2010 [19] Case series | 34 (N/A) | 53.8 ± 4.2 yrs | 71 ex 31 ex mdb 40 ex max | High-dose (34) | Oncologic (34) | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 2 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 5 d | Postop: 0.2% CHX or 10% povidone-iodine rinse | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty with piezosurgery/rongeur Drug holiday: 13 patients | 0 (12 months) | |

| Scoletta et al., 2011 [20] Prospective study | 64 (20-45) | 64.81 ± 10.98 yrs | 220 ex 113 ex mdb 107 ex max | High-dose (60; 7 patients received both Z and P) Low-dose (4) | Oncologic (60) Osteometabolic (4) | Amox-clav 1 g TID × 1 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg TID × 1 d | Amox-clav 1 g TID × 5 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg TID × 5 d | Preop: 0.12% CHX rinse BID × 7 d Postop: 3% H2O2 gauze TID × 14 d | Ostectomy and/or osteoplasty with piezosurgery, PRF | 5 (mean: 13.06 ± 1.35 months, range: 4–24 months; HD) | |

| Ferlito et al., 2011 [21] Case series | 43 (N/A) | 56.4 ± 5.8 yrs | 102 ex 43 ex mdb 59 ex max | High-dose (43) | Oncologic (43) | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 2 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 5 d | Postop: 0.2% CHX or 10% povidone-iodine rinse | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty with piezosurgery/rongeur Drug holiday: 17 patients | 0 (12 months) | |

| Carini et al., 2012 [22] Prospective study | 12 (N/A) | N/A | 18 ex 2 full-mouth ex | Low-dose (12) | N/A | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 14 d + Metro 250 mg TID × 14 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 7 d + Metro 250 mg TID × 7 d | Preop: 0.2% CHX single rinse Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse × 7 d | If low-dose < 3 yrs + risk factors or low-dose > 3 yrs: MD consult for 3 months drug holiday pre/postop | 0 (12 months) | |

| Mozzati et al., 2012 [23] Prospective study | Study group: 95 (36-55) | Range: 44–83 yrs | 275 ex 142 ex mdb 133 ex max | High-dose (180) | Oncologic (180) | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 1 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg TID × 1 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 5 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg tid × 5 d | N/A | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty, PRF, primary wound closure | 0 (range: 24–60 months) | |

| Control group: 85 (39-46) | 267 ex 145 ex mdb 122 ex max | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty, primary wound closure | 5 (range: 24–60 months; HD) | ||||||||

| Mozzati et al., 2013 [24] Prospective study | Protocol A: 334 (15-339) | Range: 52–79 yrs | 620 ex 368 ex mdb 252 ex max | Low-dose (700) | Osteometabolic (700) | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 1 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg TID × 1 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 5 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg TID × 5 d | N/A | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty, primary wound closure | 0 (range: 12–72 months) | |

| Protocol B: 366 (8-358) | 860 ex 496 ex mdb 364 ex max | Socket filled with absorbable gelatin sponge, secondary intention | |||||||||

| Scoletta et al., 2013 [25] Prospective study | 63 (18-45) | 65.82 yrs | 202 ex 111 ex mdb 91 ex max | High-dose (57) Low-dose (6) | Oncologic (57) Osteometabolic (6) | Amox-clav 1 g TID × 1 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg TID × 1 d | Amox-clav 1 g TID × 5 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg TID × 5 d | Postop: 3% H2O2 gauze tid × 14 d | Osteoplasty with piezosurgery, PRF | 1 (range: 4–12 months; HD) | |

| Vescovi et al., 2013 [26] Prospective study | 217 (38-179) | 68.72 ± 11.26 yrs | 589 ex 285 ex mdb 304 ex max | High-dose (95) Low-dose (122) | Oncologic (95) Other (122) | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 3 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 14 d | Postop: CHX + H2O2 rinse until healing | Socket irrigation with povidone-iodine solution and LLLT application PBM weekly × 6 wks + additional treatments until healing | 5 (mean: 15 months, range: 4–31 months; HD) | |

| Hutcheson et al., 2014 [47] Prospective study | 618 (N/A) | N/A | N/A | Low-dose (618) | Osteometabolic (618) | Amox-clav 2 g 1 h preop If allergy: Clinda 600 mg 1 h preop | No postoperative therapy | Postop: 10 mL CHX rinse TID × 7 d | If CTX < 150 pg/mL: drug holiday | 3 (minimum FU 2 months; LD) | |

| Bodem et al., 2015 [33] Prospective study | 61 (19-42) | 66.65 ± 12.69 yrs | 184 ex 47 ex mdb 55 ex max | High-dose (61) | Oncologic (61) | Amp-sulb IV 1.5 g TID × 1 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID × 1 d | Amp-sulb IV 1.5 g TID × 5 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID × 5 d | 0.12% CHX rinse TID | Mucosal flap if requested, osteotomy if requested, tension-free closure | 8 (3 months; HD) | |

| Otto et al., 2015 [34] Retrospective cohort study | 72 (19-53) | 67.5 yrs | 216 ex 97 ex mdb 119 ex max | High-dose (43) Low-dose (29) | Oncologic (43) Osteometabolic (29) | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 1 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID × 1 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID until mucosal healing If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID until mucosal healing | N/A | Atraumatic ex, osteoplasty, mucosal wound closure | 5 (mean: 14.9 months; 4 HD, 1 LD) | |

| Matsumoto et al., 2017 [39] Retrospective study | 19 (6-13) | 69.3 yrs | 40 ex 19 ex mdb 21 ex max | High-dose (14) Low-dose (5) | Oncologic (14) Osteometabolic (5) | Penic IV 10M U.I. x 1 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID × 1 d | Penic IV 10M U.I: x 1 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID × 1 d | N/A | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty, primary wound closure | 2 (minimum FU 3 months; HD) | |

| Shudo et al., 2018 [40] Prospective study | 132 (20-112) | 71.9 ± 11.4 yrs | 274 ex 109 ex mdb 165 ex max | Low-dose (132) | Osteometabolic (77) Osteoporosis prevention (55) | Amox ≥ 250 mg 1 h preop or Clarithro ≥ 200 mg 1 h preop | Amox 1 g OD up to 2 d or Clarithro 400 mg OD up to 2 d | N/A | Atraumatic ex, tension-free wound closure | 0(minimum FU 3 months) | |

| Poli et al., 2019 [27] Case series | 11 (3-8) | 72.5 ± 4.2 yrs | 62 ex 35 ex mdb 27 ex max | Low-dose (11) | Osteometabolic (11) | Amox 1 g TID × 3 d | Amox 1 g TID × 17 d | Preop: 0.2% CHX rinse bid × 14 d Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse BID × 14 d | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty, aPDT with methylene blue + diode laser, primary wound closure Drug holiday: 2 months before ex until healing if BPs < 3yrs (4 patients) | 0 (range: 6–12 months) | |

| Şahin et al., 2020 [49] Retrospective study | 44 (12-32) | 66.3 yrs | 63 ex 40 ex mdb 23 ex max | High-dose (18) Low-dose (26) | Oncologic (21) Osteometabolic (23) | Amox-clav 1 g OD × 3 d + Metro 500 mg OD × 3 d | Amox-clav 1 g OD × 14 d + Metro 500 mg OD × 14 d | Preop: 0.12% CHX rinse × 3 d Postop: 0.12% CHX rinse × 14 d | Sulcular incision if requested, osteoplasty with burs, PRF + Nd: YAG laser biostimulation on 2, 5, 7, 10, 14, 21, and 28 d, primary wound closure | 0 (mean: 14.2 months, range: 6–28 months) | |

| Spanou et al., 2020 [35] Retrospective study | 84 (17-67) | 71.7 yrs | 232 ex 125 ex mdb 107 ex max | High-dose (40) Low-dose (53; 18 patients received two different BPs) | Oncologic (39) Osteometabolic (44) Other (1) | Penic IV 10M U.I. × 1 d + If purulent infection: Metro 500 mg bid × 1 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg tid × 1 d | Penic IV 10M U.I. × 3 d + If purulent infection: Metro 500 mg bid × 3 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg tid × 1 d | Preop: CHX single rinse Postop: CHX rinse ≥ 2–3 wks until mucosal healing | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty, primary wound closure | 2 (mean: 41.5 ± 29.5 months, range: 2–109 months; 1 HD, 1 LD) | |

| Tartaroti et al., 2020 [42] Case series | 17 (0-17) | 68.94 ± 11.72 yrs | 37 ex 20 ex mdb 17 ex max | High-dose (5) Low-dose (12) | Oncologic (5) Osteometabolic (12) | Amox 500 mg TID × 1 d If allergy: Clinda 300 g TID × 1 d or Amp 400 mg BID × 1 d | Amox 500 mg TID × 6 d If allergy: Clinda 300 g TID × 6 d or Amp 400 mg BID × 6 d | Preop: 0.12% CHX rinse Postop: 0.12% CHX rinse | aPDT with methylene blue + diode laser, repeated weekly until healing If pain/edema postop: PBM therapy Drug holiday: 6 patients | 0 (minimum FU 6 months) | |

| Mauceri et al., 2020 [28] Prospective study | 20 (4-16) | 72.35 ± 7.19 yrs | 63 ex 30 ex mdb 33 ex max | High-dose (6) Low-dose (14) | Oncologic (6) Osteometabolic (14) | Amox-clav 1 g TID × 1 d + Metro 250 mg BID × 1 d | Amox-clav 1 g TID × 7 d + Metro 250 mb BID × 7 d | Preop: 0.2% CHX rinse tid × 7 d Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse tid × 15 d + Na-hyaluronate gel tid × 10 d | Mucoperiosteal flap, osteoplasty with piezosurgery, PRP, tension-free wound closure | 0 (minimum FU 24 months) | |

| Poxleitner et al., 2020 [36] Prospective study | Primary closure group: 39 (0-39) | 77 yrs | Interventions: 19 mdb 13 max 7 both | Low-dose (77) | Osteometabolic (77) | Penic IV 10M U.I. × 1 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID × 1 d | Penic IV 10M U.I. × 1 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID × 1 d | Preop: CHX single rinse Postop: CHX rinse until healing | Sulcular incision for atraumatic ex, mucoperiosteal flap, primary tension-free closure | 0 (3 months) | |

| PRF group: 38 (1-37) | 78 yrs | Interventions: 20 mdb 16 max 2 both | Sulcular incision for atraumatic ex, PRF without primary closure | ||||||||

| Lesclous et al., 2020 [52] Prospective study | 44 (0-44) | 70 yrs | N/A | Low-dose (44) | Osteometabolic (44) | If local infection (13 patients): Amox 1 g BID × 6–7 d If local infection + allergy: Clinda 600 mg BID × 6–7 d | No postoperative therapy | Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse TID × 7 d | Atraumatic ex, tension-free wound closure and full-closure not mandatory | 0 (3 months) | |

| Sandhu et al., 2020 [51] Retrospective study | 40 (20-20) | 65 yrs | 26 single ex 14 multiple ex | High-dose (37) Low-dose (3) | Oncologic (37) Osteometabolic (3) | No antibiotic prophylaxis | Amox 500 mg TID × 14 d If signs of infection at 14 d follow-up visit: Amox 500 mg TID × additional 14 d (4 patients) | Postop: 0.12% CHX rinse BID until healing | Atraumatic ex, saline irrigation of socket and primary wound closure if possible | 3 (2 wks; HD) | |

| Ristow et al., 2020 [37] Randomized pilot trial | Subperiosteal flap group: 82 (25-57) | 68.4 ± 9.6 yrs | 475 ex | High-dose (46) Low-dose (36) | Oncologic (46) Osteometabolic (36) | Amp-sulb 375 mg BID × 7 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg × 7 d | Amp-sulb 375 mg BID × 7 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg × 7 d | Preop: 0.2% CHX rinse tid × 2 d Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse tid ≥ 5 d | Sulcular incision, mucoperiosteal flap, alveoloplasty, primary wound closure Drug holiday: 30 d pre to 30 d postop after MD consult | 5 (2 months; 3 HD, 2 LD) | |

| Epiperiosteal flap group: 78 (18-60) | 67.8 ± 10.1 yrs | High-dose (41) Low-dose (37) | Oncologic (41) Osteometabolic (37) | Sulcular incision, mucosal flap, alveoloplasty, primary wound closure Drug holiday: 30 d pre to 30 d postop after MD consult | 18 (2 months; 13 HD, 5 LD) | ||||||

| Miranda et al., 2021 [29] Retrospective study | Study group: 11 (0-11) | 74.81 yrs | 27 ex 18 ex mdb 9 ex max | High-dose (1) Low-dose (10) | Oncologic (6) Osteometabolic (5) | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 5 d + Metro 250 mg BID × 2 d If allergy: Azithro 500 mg 2h before ex | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 5 d + Metro 250 mg BID × 2 d If allergy: Azithro 500 mg OD × 5 d | N/A | Delicate curettage, PRF, suture without flap | 0 (6 months) | |

| Control group: 26 (1-25) | 70.69 yrs | 42 ex 27 ex mdb 15 ex max | High-dose (2) Low-dose (24) | Oncologic (12) Osteometabolic (14) | Delicate curettage, suture without flap | 5 (6 months; 2 HD, 3 LD) | |||||

| Barry et al., 2021 [45] Retrospective study | 652 (109-543) | 69.7 yrs | 652 ex 258 ex mdb 297 ex max 97 ex both | Low-dose (652) | Oncologic (9) Osteometabolic (643) | No antibiotic prophylaxis | If high risk patients (low dose ≥ 4yrs or < 4yrs + corticosteroids): Amox 500 mg TID × 5 d If allergy: Metro 400 mg tid × 5 d | Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse tid until healing | Atraumatic ex | 5 (12 months, LD) | |

| Pippi et al., 2021 [30] Retrospective case series | Protocol n.2: 13 | 68.02 ± 11.17 yrs | 639 ex 321 ex mdb 318 ex max | High-dose (22) Low-dose (197) | Oncologic (22) Osteometabolic (197) | Amox 1 g BID × 3 d | Amox 1 g BID × 6 d | Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse × 7 d | Non-surgical ex, secondary intention healing | 0(until mucosal healing, mean: 2 wks, range: 1–3 wks) | |

| Protocol n.3: 206 | Amox 1 g BID × 3 d + Metro 500 mg BID × 3 d | Amox 1 g BID × 6 d + Metro 500 mg BID × 6 d | |||||||||

| Parise et al., 2022 [43] Case–control study | Group 1 (control): 7 (2-5) | 59.43 yrs | 7 ex 5 ex mdb 2 ex max | High-dose (15) | Oncologic (15) | Amox 500 mg TID × 7 d + Metro 400 mg TID × 7 d | Amox 500 mg TID × 7 d + Metro 400 mg TID × 7 d | Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse BID | Mucoperiosteal flap (if necessary), bone edge smoothing, tension-free closure | 2 (6 months; HD) | |

| Group 2 (prevention): 8 (3-5) | 58.38 yrs | 8 ex 4 ex mdb 4 ex max | Mucoperiosteal flap (if necessary), bony edge smoothing, PRF, tension-free closure | 0 (6 months) | |||||||

| Seki et al., 2022 [41] Retrospective study | 40 (N/A) | 77.5 ± 7.9 yrs | 70 ex 41 ex mdb 29 ex max | Low-dose (40) | Osteometabolic (40) | No antibiotic prophylaxis | Amox TID × 3 d | N/A | Drug holiday: 6.9 months (mean duration) | 2 (122.6 ± 170 d; LD) | |

| Cuozzo et al., 2022 [31] Prospective study | Low risk: 20 | 67.5 ± 3 yrs | 54 ex | Low-dose (45) | Osteometabolic (45) | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 3 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 3 d | Preop: 0.2% CHX rinse OD × 7 d Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse OD × 7 d | Atraumatic ex, bony edge smoothening, tension-free closure Drug holiday: 27 patients | 0 (12 months) | |

| Low/medium risk: 18 | 48 ex | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 3 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 12 d | 1 (12 months; LD) | |||||||

| Medium risk: 3 | 38 ex | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 3 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 20 d | 0 (12 months) | |||||||

| High risk: 4 | 19 ex | Ceftr 1 g IM × 2 d | Ceftr 1 g IM × 5 d + Amox-clav 1 g BID × 7 d | 0 (12 months) | |||||||

| Karaca et al., 2023 [50] Retrospective study | 51 (14-37) | 57.21 ± 10.21 yrs | 109 ex 73 ex mdb 49 ex max | High-dose (51) | Oncologic (51) | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 2 d If allergy: Clinda 150 mg OD × 4 d | Amox-clav 1 g BID × 3 d If allergy: Clinda 150 mg OD × 3 d | Postop: 0.12% CHX rinse tid × 7 d | Atraumatic ex, osteoplasty, primary wound closure Drug holiday: 2 months (median duration), 31 patients | 3 (8 wks; HD) | |

| Ristow et al., 2023 [38] Retrospective study | 759 (219-540) | N/A | Group 1 (IV): 719 ex 368 ex mdb 351 ex max | High-dose (452) Low-dose (307) | Oncologic (452) Osteometabolic (307) | Amp-sulb 1.5 g × 1 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg os or 600 mg/4 mL IV | Amp-sulb 1.5 g × 6 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg os or 600 mg/4 mL IV | Preop: 0.2% CHX rinse TID × 10/14 d Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse TID × 10/14 d | Mucoperiosteal flap, alveoloplasty, primary wound closure Drug holiday: 30 d pre to 30 d postop after MD consult | 50 sites | (3 months; 66 sites HD, 10 sites LD) |

| Group 2 (two wks): 298 ex 150 ex mdb 148 ex max | Amox-clav 1 g × 7 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg os or 600 mg/4 mL IV | Amox-clav 1 g × 7 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg os or 600 mg/4 mL IV | 17 sites | ||||||||

| Group 3 (one wk): 126 ex 60 ex mdb 66 ex max | Amox-clav 1 g × 5 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg os or 600 mg/4 mL IV | Amox—clav 1 g × 5 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg os or 600 mg/4 mL IV | 9 sites | ||||||||

| Megalhaes et al., 2023 [44] Case series | 17 (2-15) | 55 yrs | 32 ex 10 ex mdb 22 ex max | High-dose (17) | Oncologic (17) | Amox 500 mg TID × 2 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID × 2 d + Metro 400 mg TID × 2 d | Amox 500 mg TID × 8 d If allergy: Clinda 600 mg TID × 8 d + Metro 400 mg TID × 8 d | Postop: 0.12% CHX rinse TID until suture removal | Pentoxifylline 400 mg and tocopherol 400 IU tid 15 d preop and 15 d postop | 3 (3 months; HD) | |

| Besi et al., 2024 [46] Observational study | L-PRF group: 15 (4-11) | 75 yrs | 22 ex 13 ex mdb 9 ex max | High-dose (2) Low-dose (13) | Oncologic (2) Osteometabolic (13) | No antibiotic prophylaxis | No postoperative therapy | Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse | Atraumatic ex, bony edge smoothening, PRF, primary closure (if possible) | 0 (mean: 3 months) | |

| Control group: 24 (6-18) | 70 yrs | 41 ex 20 ex mdb 21 ex max | High-dose (7) Low-dose (17) | Oncologic (7) Osteometabolic (17) | Atraumatic ex, bony edge smoothening, primary closure (if possible) | 5 (mean: 10 wks; HD) | |||||

| Di Fede et al., 2024 [32] Randomized clinical trial | Test group: 38 (11-27) | 66.7 yrs | N/A | High-dose (22) Low-dose (16) | Oncologic (26) Osteometabolic (12) | Amox-Clav 1 g TID × 1 d + Metro 500 mg TID × 1 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg tid × 1 d + Metro 500 mg TID × 1 d | Amox-Clav 1 g TID × 6 d + Metro 500 mg TID × 6 d If allergy: Erythro 600 mg TID × 6 d + Metro 500 mg TID × 6 d | Postop: 0.2% CHX rinse | Alveoloplasty, O2-O3 injections (perialveolar and post-ex site), primary wound closure. Additional O2-O3 at 3–5 d, 14 d, and 6 wks | N/A | |

| Control group: 79 (16-63) | 69.6 yrs | High-dose (35) Low-dose (44) | Oncologic (37) Osteometabolic (42) | Alveoloplasty, primary wound closure | |||||||

| Chang et al., 2025 [48] Retrospective study | 329 (82-247) | 74 yrs | 836 yrs | High-dose (19) Low-dose (310) | Oncologic (19) Osteometabolic (310) | Low risk: No prophylaxis If high risk: Amox 2 g 1 h preop If allergy: Clinda 600 mg 1 h preop | If high risk + immunocompromised, spreading odontogenic infection: postoperative therapy | Preop: CHX rinse Postop: CHX rinse | Primary wound closure if tooth required to be surgically extracted | 18 (8 wks; N/A) | |

| Analysis Model | OR | 95% CI | z | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Common-effect model | 3.26 | 1.74–6.10 | 3.69 | 0.0002 |

| Random-effects model | 2.82 | 1.46–5.43 | 3.08 | 0.0020 |

| Predictor | β (Estimate) | SE | z Value | p Value | OR | 95% CI (OR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept (low-dose, 0 days) | −5.75 | 0.76 | −7.59 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.001–0.012 |

| Antibiotic days (low-dose) | +0.06 | 0.07 | +0.93 | 0.352 | 1.06 | 0.93–1.22 |

| High dose (vs. low dose) | +3.51 | 0.86 | +4.10 | <0.001 | 33.5 | 6.3–177.8 |

| Days × High dose (interaction) | −0.15 | 0.07 | −2.22 | 0.026 | 0.86 | 0.75–0.98 |

| PubMed | Scopus | Web of Science |

|---|---|---|

| ((“prevention” [All Fields] OR “antibiotic” [All Fields] OR “prophylaxis” [All Fields]) AND (“dental extraction” [All Fields] OR “extraction” [All Fields] OR “tooth extraction” [All Fields] OR “teeth extraction” [All Fields] OR “dental avulsion” [All Fields]) AND (“osteonecrosis” [All Fields] OR “osteonecrosis of the jaw” [All Fields] OR “bone necrosis” [All Fields] OR “jaw necrosis” [All Fields] OR “ONJ” [All Fields] OR “BRONJ” [All Fields] OR “MRONJ” [All Fields]) OR “ARONJ” [All Fields]) | ((“prevention” [all AND fields] OR “antibiotic” [all AND fields] OR “prophylaxis” [all AND fields]) AND (“dental extraction” [all AND fields] OR “extraction” [all AND fields] OR “tooth extraction” [all AND fields] OR “teeth extraction” [all AND fields] OR “dental avulsion” [all AND fields]) AND (“osteonecrosis” [all AND fields] OR “osteonecrosis of the jaw” [all AND fields] OR “bone necrosis” [all AND fields] OR “jaw necrosis” [all AND fields] OR “ONJ” [all AND fields] OR “BRONJ” [all AND fields] OR “MRONJ” [all AND fields]) OR “ARONJ” [all AND fields]) | ALL = ((prevention OR antibiotic OR prophylaxis) AND (dental extraction OR extraction OR tooth extraction OR teeth extraction OR dental avulsion) AND (osteonecrosis OR osteonecrosis of the jaw OR bone necrosis OR jaw necrosis OR onj OR bronj OR mronj OR aronj)) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barone, S.; Antonelli, A.; Madonna, A.; Giudice, A.; Borelli, M.; Bennardo, F. Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Postoperative Therapy in Tooth Extractions for Patients at Risk of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ): A Scoping Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121279

Barone S, Antonelli A, Madonna A, Giudice A, Borelli M, Bennardo F. Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Postoperative Therapy in Tooth Extractions for Patients at Risk of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ): A Scoping Review. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121279

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarone, Selene, Alessandro Antonelli, Antonio Madonna, Amerigo Giudice, Massimo Borelli, and Francesco Bennardo. 2025. "Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Postoperative Therapy in Tooth Extractions for Patients at Risk of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ): A Scoping Review" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121279

APA StyleBarone, S., Antonelli, A., Madonna, A., Giudice, A., Borelli, M., & Bennardo, F. (2025). Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Postoperative Therapy in Tooth Extractions for Patients at Risk of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw (MRONJ): A Scoping Review. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121279