Biofilm Production, Distribution of ica Genes, and Antibiotic Resistance in Clinical Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolates

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacterial Isolates

2.2. Bacterial Identification

2.3. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

2.4. Microtiter Plate (MTP) Assay for Detecting Biofilm Formation Capacity

- OD ≤ ODc ⇒ no biofilm production (biofilm-negative)

- ODc < OD ≤ 2 ODc ⇒ weak biofilm producer

- 2 ODc < OD ≤ 4 ODc ⇒ moderate biofilm producer

- 4 ODc < OD ⇒ strong biofilm producer

2.5. DNA Isolation and Real-Time PCR

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

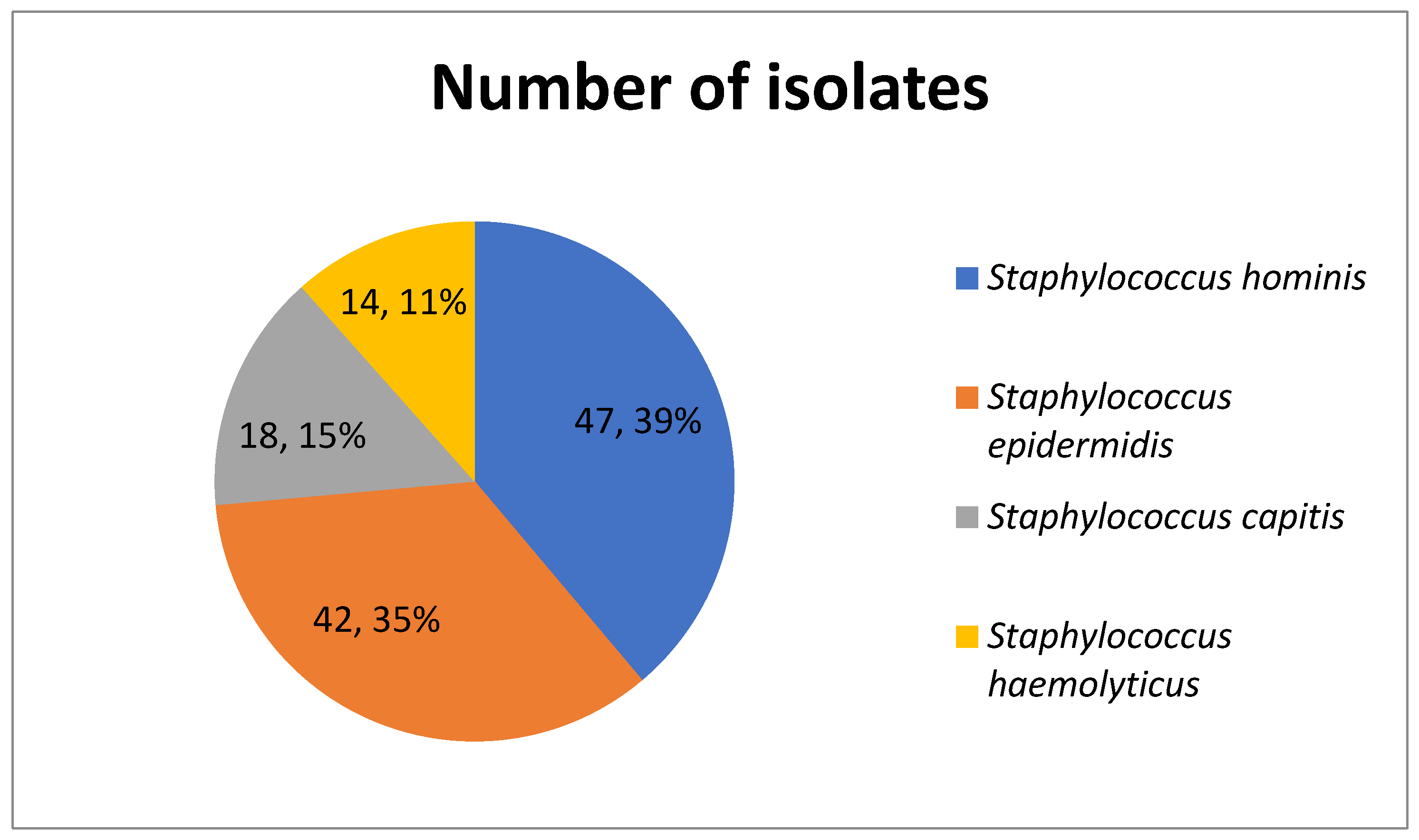

3.1. Distribution of Isolates

3.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

3.3. Biofilm Production

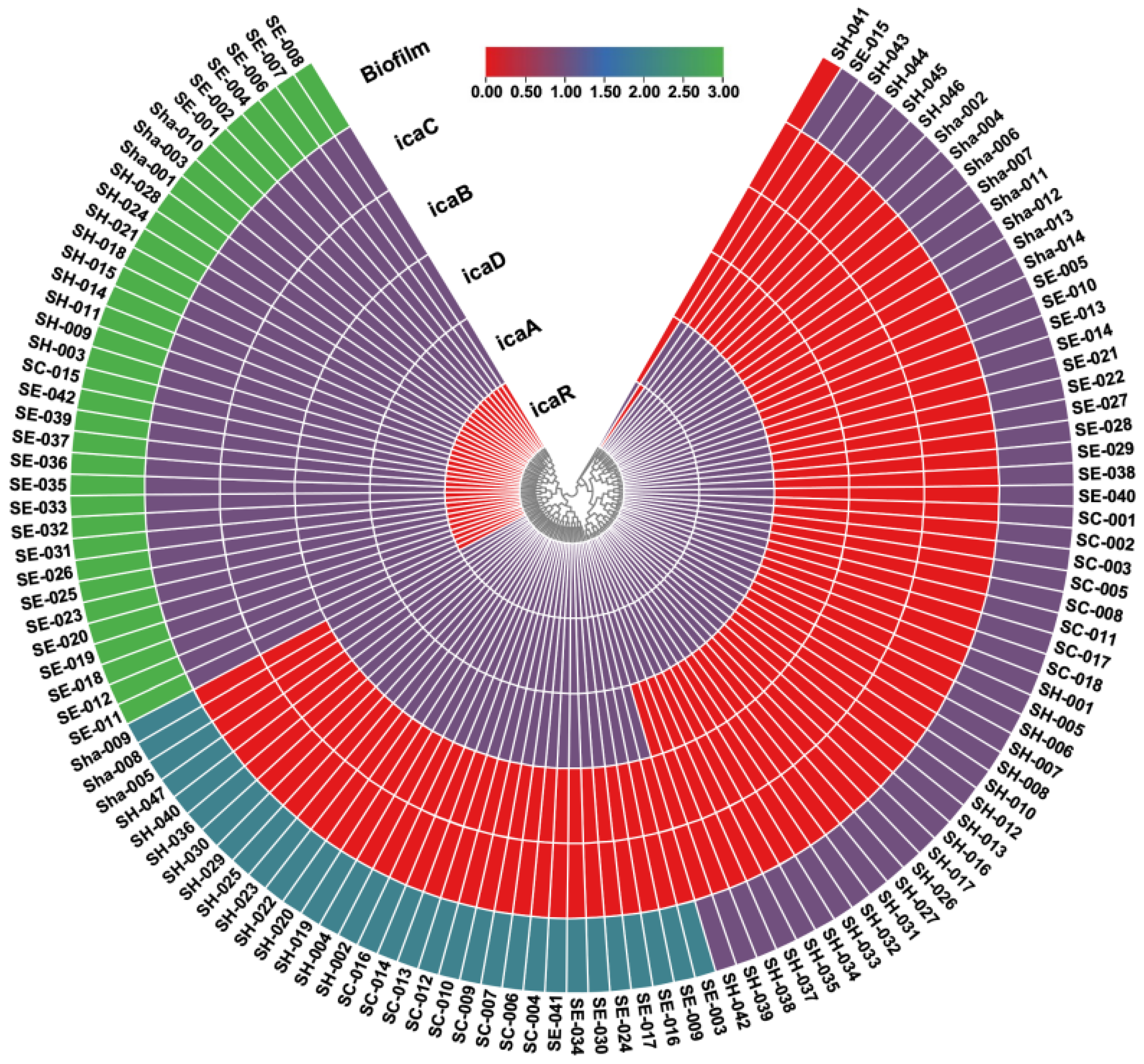

3.4. Biofilm-Related Genes

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grassia, G.; Bagnarino, J.; Siciliano, M.; Barbarini, D.; Corbella, M.; Cambieri, P.; Baldanti, F.; Monzillo, V. Phenotypic and Genotypic Assays to Evaluate Coagulase Negative Staphylococci Biofilm Production in Bloodstream Infections. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suepaul, S.; Georges, K.; Unakal, C.; Boyen, F.; Sookhoo, J.; Ashraph, K.; Yusuf, A.; Butaye, P. Determination of the frequency, species distribution and antimicrobial resistance of staphylococci isolated from dogs and their owners in Trinidad. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0254048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lean, S.S.; Wetthasinghe, L.; Sim, K.S.; Chong, H.X.; Bin Sharfudeen, S.I.; Chen, Y.W.; Lim, Y.Y.; Teoh, H.K.; Yeo, C.C.; Ng, H.F. Genomic characterisation of nasal isolates of coagulase-negative Staphylococci from healthy medical students reveals novel Staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec elements. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 21770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- França, A.; Gaio, V.; Lopes, N.; Melo, L.D.R. Virulence Factors in Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci. Pathogens 2021, 10, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowrouzian, F.L.; Lumingkit, K.; Gio-Batta, M.; Jaén-Luchoro, D.; Thordarson, T.; Elfvin, A.; Wold, A.E.; Adlerberth, I. Tracing Staphylococcus capitis and Staphylococcus epidermidis strains causing septicemia in extremely preterm infants to the skin, mouth, and gut microbiota. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2025, 91, e0098024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Frickmann, H.; Hahn, A.; Skusa, R.; Mund, N.; Viehweger, V.; Köller, T.; Köller, K.; Schwarz, N.G.; Becker, K.; Warnke, P.; et al. Comparison of the etiological relevance of Staphylococcus haemolyticus and Staphylococcus hominis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018, 37, 1539–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooters, K.E.; Hayes, S.L.; Richter, D.M.; Ku, J.C.; Sawyer, R.; Li, Y. A novel strategy for eradication of staphylococcal biofilms using blood clots. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2025, 15, 1507486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, C.; Ziebuhr, W.; Becker, K. Are coagulase-negative staphylococci virulent? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2019, 25, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.W.K.; Millar, B.C.; Moore, J.E. Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). Br. J. Biomed. Sci. 2023, 80, 11387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Keogh, S.; Larsen, E.N.; Edwards, F.; Totsika, M.; Marsh, N.; Harris, P.N.A.; Laupland, K.B. Speciation of coagulase-negative staphylococci: A cohort study on clinical relevance and outcomes. Infect. Dis. Health 2025, 30, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cafiso, V.; Bertuccio, T.; Santagati, M.; Campanile, F.; Amicosante, G.; Perilli, M.G.; Selan, L.; Artini, M.; Nicoletti, G.; Stefani, S. Presence of the ica operon in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus epidermidis and its role in biofilm production. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2004, 10, 1081–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz de los Mozos, I.; Vergara-Irigaray, M.; Segura, V.; Villanueva, M.; Bitarte, N.; Saramago, M.; Domingues, S.; Arraiano, C.M.; Fechter, P.; Romby, P.; et al. Base pairing interaction between 5′- and 3′-UTRs controls icaR mRNA translation in Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS Genet. 2013, 9, e1004001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Otto, M. Staphylococcal Biofilms. Microbiol. Spectr. 2018, 6, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modak, S.; Mane, P.; Patil, S. A Comprehensive Phenotypic Characterization of Biofilm-Producing Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci: Elucidating the Complexities of Antimicrobial Resistance and Susceptibility. Cureus 2025, 17, e79039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Christensen, G.D.; Simpson, W.A.; Younger, J.J.; Baddour, L.M.; Barrett, F.F.; Melton, D.M.; Beachey, E.H. Adherence of coagulase-negative staphylococci to plastic tissue culture plates: A quantitative model for the adherence of staphylococci to medical devices. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1985, 22, 996–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ghaioumy, R.; Tabatabaeifar, F.; Mozafarinia, K.; Mianroodi, A.A.; Isaei, E.; Morones-Ramírez, J.R.; Afshari, S.A.K.; Kalantar-Neyestanaki, D. Biofilm formation and molecular analysis of intercellular adhesion gene cluster (icaABCD) among Staphylococcus aureus strains isolated from children with adenoiditis. Iran. J. Microbiol. 2021, 13, 458–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schwartbeck, B.; Rumpf, C.H.; Hait, R.J.; Janssen, T.; Deiwick, S.; Schwierzeck, V.; Mellmann, A.; Kahl, B.C. Various mutations in icaR, the repressor of the icaADBC locus, occur in mucoid Staphylococcus aureus isolates recovered from the airways of people with cystic fibrosis. Microbes Infect. 2024, 26, 105306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, K.L.; Fey, P.D.; Rupp, M.E. Coagulase-negative staphylococcal infections. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2009, 23, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manandhar, S.; Singh, A.; Ajit Varma, A.; Shanti Pandey, S.; Neeraj Shrivastava, N. Phenotypic and genotypic characterization of bioflm producing clinical coagulase negative staphylococci from Nepal and their antibiotic susceptibility pattern. Ann. Clin. Microbiol. Antimicrob. 2021, 20, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marek, A.; Pyzik, E.; Stępień-Pyśniak, D.; Dec, M.; Jarosz, Ł.S.; Nowaczek, A.; Sulikowska, M. Biofilm-Formation Ability and the Presence of Adhesion Genes in Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolates from Chicken Broilers. Animals 2021, 11, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, H.; Ziegler, D.; Pflüger, V.; Vogel, G.; Zweifel, C.; Stephan, R. Prevalence and characteristics of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci from livestock, chicken carcasses, bulk tank milk, minced meat, and contact persons. BMC Vet. Res. 2011, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lebeaux, D.; Barbier, F.; Angebault, C.; Benmahdi, L.; Ruppé, E.; Felix, B.; Gaillard, K.; Djossou, F.; Epelboin, L.; Dupont, C.; et al. Evolution of nasal carriage of methicillin-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci in a remote population. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 315–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruppé, E.; Barbier, F.; Mesli, Y.; Maiga, A.; Cojocaru, R.; Benkhalfat, M.; Benchouk, S.; Hassaine, H.; Maiga, I.; Diallo, A.; et al. Diversity of staphylococcal cassette chromosome mec structures in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis and Staphylococcus haemolyticus strains among outpatients from four countries. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 442–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, E.M.; Ceotto, H.; Bastos, M.C.F.; Dos Santos, K.R.N.; Giambiagi-deMarval, M. Staphylococcus haemolyticus as an important hospital pathogen and carrier of methicillin resistance genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2012, 50, 166–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, K.; Heilmann, C.; Peters, G. Coagulase-negative Staphylococci. Am. Soc. Microbiol. 2014, 27, 870–926. [Google Scholar]

- Kosowska-Shick, K.; Julian, K.G.; McGhee, P.L.; Appelbaum, P.C.; Whitener, C.J. Molecular and epidemiologic characteristics of linezolid-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci at a tertiary care hospital. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 68, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balandin, B.; Lobo, B.; Orden, B.; Román, F.; García, E.; Martínez, R.; Valdivia, M.; Ortega, A.; Fernández, I.; Galdos, P. Emergence of linezolid-resistant coagulase-negative staphylococci in an intensive care unit. Infect. Dis. 2016, 48, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grari, O.; Ezrari, S.; El Yandouzi, I.; Benaissa, E.; Ben Lahlou, Y.; Lahmer, M.; Saddari, A.; Elouennass, M.; Maleb, A. A comprehensive review on biofilm-associated infections: Mechanisms, diagnostic challenges, and innovative therapeutic strategies. Microbe 2025, 8, 100436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, C.; Ma, T.M.; Sim, J.; Altheim, C.; Martinez-Nieves, E.; Kadiyala, U.; Solomon, M.J.; VanEpps, J.S. Staphylococcus epidermidis Has Growth Phase Dependent Affinity for Fibrinogen and Resulting Fibrin Clot Elasticity. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 649534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Altunova, H.; Kılıç, İ.H. Presence of biofilm-associated genes in clinical staphylococcal isolates and antibiofilm activities of some mucolytic compounds against these strains. Biologia 2025, 80, 2171–2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E.C.; Kowalski, R.P.; Romanowski, E.G.; Mah, F.S.; Gordon, Y.J.; Shanks, R.M.Q. AzaSite Inhibits Staphylococcus aureus and Coagulase-Negative Staphylococcus Biofilm Formation In Vitro. J. Ocul. Pharmacol. Ther. 2010, 26, 557–562. [Google Scholar]

- França, A. The Role of Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Biofilms on Late-Onset Sepsis: Current Challenges and Emerging Diagnostics and Therapies. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryder, V.J.; Chopra, I.; O’Neill, A.J. Increased Mutability of Staphylococci in Biofilms as a Consequence of Oxidative Stress. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, N.; Ellington, M.J. The Emergence of Antibiotic Resistance by Mutation. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2007, 13, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dengler Haunreiter, V.; Boumasmoud, M.; Häffner, N.; Wipfli, D.; Leimer, N.; Rachmühl, C.; Kühnert, D.; Achermann, Y.; Zbinden, R.; Benussi, S.; et al. In-host evolution of Staphylococcus epidermidis in a pacemaker-associated endocarditis resulting in increased antibiotic tolerance. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Nguyen, T.H.; Otto, M. The staphylococcal exopolysaccharide PIA—Biosynthesis and role in biofilm formation, colonization, and infection. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2020, 18, 3324–3334, Erratum in Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2023, 21, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Q.; Tang, X.; Dong, W.; Sun, N.; Yuan, W. A Review of Biofilm Formation of Staphylococcus aureus and Its Regulation Mechanism. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alibegli, M.; Bay, A.; Fazelnejad, A.; Ghezelghaye, P.N.; Soghondikolaei, H.J.; Goli, H.R. Contribution of icaADBC genes in biofilm production ability of Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates collected from hospitalized patients at a burn center in North of Iran. BMC Microbiol. 2025, 25, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillip, S.; Mushi, M.F.; Decano, A.G.; Seni, J.; Mmbaga, B.T.; Kumburu, H.; Konje, E.T.; Mwanga, J.R.; Kidenya, B.R.; Msemwa, B.; et al. Molecular Characterizations of the Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Species Causing Urinary Tract Infection in Tanzania: A Laboratory-Based Cross-Sectional Study. Pathogens 2023, 12, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Azmi, K.; Qrei, W.; Abdeen, Z. Screening of genes encoding adhesion factors and biofilm production in methicillin resistant strains of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Palestinian patients. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, T.; Zhou, C.; Lindgren, J.K.; Galac, M.R.; Corey, B.; Endres, J.E.; Olson, M.E.; Fey, P.D. Transcriptional Regulation of icaADBC by both IcaR and TcaR in Staphylococcus epidermidis. J. Bacteriol. 2019, 201, e00524-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramton, S.E.; Gerke, C.; Schnell, N.F.; Nichols, W.W.; Götz, F. The intercellular adhesion (ica) locus is present in Staphylococcus aureus and is required for biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 1999, 67, 5427–5433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piechota, M.; Kot, B.; Frankowska-Maciejewska, A.; Grużewska, A.; Woźniak-Kosek, A. Biofilm formation by methicillin-resistant and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus strains from hospitalized patients in Poland. Biomed Res Int. 2018, 2018, 4657396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seng, R.; Kitti, T.; Thummeepak, R.; Kongthai, P.; Leungtongkam, U.; Wannalerdsakun, S.; Sitthisak, S. Biofilm formation of methicillin-resistant coagulase negative staphylococci (MR-CoNS) isolated from community and hospital environments. PLoS ONE 2017, 8, e0184172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazul, M.; Balcerczak, E.; Sienkiewicz, M. Analysis of the Presence of the Virulence and Regulation Genes from Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) in Coagulase Negative Staphylococci and the Influence of the Staphylococcal Cross-Talk on Their Functions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 5155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kord, M.; Ardebili, A.; Jamalan, M.; Jahanbakhsh, R.; Behnampour, N.; Ghaemi, E.A. Evaluation of Biofilm Formation and Presence of Ica Genes in Staphylococcus epidermidis Clinical Isolates. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect. 2018, 9, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Shrestha, L.B.; Bhattarai, N.R.; Khanal, B. Antibiotic resistance and biofilm formation among coagulase-negative staphylococci isolated from clinical samples at a tertiary care hospital of eastern Nepal. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2017, 6, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitti, T.; Seng, R.; Thummeepak, R.; Boonlao, C.; Jindayok, T.; Sitthisak, S. Biofilm Formation of Methicillin-resistant Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolated from Clinical Samples in Northern Thailand. J. Glob. Infect. Dis. 2019, 11, 112–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Target Gene | Primer Sequence 5′→ 3′ | Amplicon Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| icaA | F5′TCTCTTGCAGGAGCAATCAA R5′TCAGGCACTAACATCCAGCA | (188 bp) | Grassia, G. et al., 2024 [1] |

| icaB | F5′ATGGCTTAAAGCACACGACGC R5′TATCGGCATCTGGTGTGACAG | (526 bp) | Grassia, G. et al., 2024 [1] |

| icaC | F5′ATCATCGTGACACACTTACTAACG R5′CTCTCTTAACATCATTCCGACGCC | (934 bp) | Grassia, G. et al., 2024 [1] |

| icaD | F5′ATGGTCAAGCCCAGACAGAG R5′CGTGTTTTCAACATTTAATGCAA | (198 bp) | Grassia, G. et al., 2024 [1] |

| icaR | F5′CAATATCGATTTGTATTGTCAACTTT R5′GGTTGTAAGCCATATGGTAATTGA | (798 bp) | Schwartbeck et al., 2024 [17] |

| CoNS Species | Blood Culture n (%) | Catheter Blood Culture n (%) | Urethral Discharge Culture n (%) | Wound Culture n (%) | Other n (%) | Total Isolates (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Staphylococcus hominis | 44 (93.61%) | 2 (4.25%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.12%) | 47 |

| Staphylococcus epidermidis | 34 (80.95%) | 5 (11.90%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (7.14%) | 0 (0%) | 42 |

| Staphylococcus capitis | 14 (77.78%) | 4 (22.22%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 18 |

| Staphylococcus haemolyticus | 10 (71.43%) | 3 (21.43%) | 1 (7.14%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 14 |

| Total isolates | 102 (84.30%) | 14 (11.57%) | 1 (0.83%) | 3 (2.48%) | 1 (0.83%) | 121 |

| Antibiotics | S. hominis (n = 47) | S. epidermidis (n = 42) | S. capitis (n = 18) | S. haemolyticus (n = 14) | Total Isolates (n = 121) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S (%) | R (%) | I (%) | S (%) | R (%) | I (%) | S (%) | R (%) | I (%) | S (%) | R (%) | I (%) | S (%) | R (%) | I (%) | |

| Oxacillin | 10.8 | 89.1 | 0 | 19 | 81 | 0 | 11.1 | 88.9 | 0 | 14.3 | 85.7 | 0 | 14.1 | 85.8 | 0 |

| Levofloxacin | 0 | 70.2 | 29.8 | 0 | 71.4 | 28.6 | 0 | 88.9 | 11.1 | 0 | 85.7 | 14.3 | 0 | 75.2 | 24.8 |

| Erythromycin | 12.8 | 87.2 | 0 | 23.8 | 76.2 | 0 | 11.1 | 88.9 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0.0 | 14.9 | 85.1 | 0 |

| Clindamycin | 31.1 | 68.8 | 0 | 38.1 | 61.9 | 0 | 11.1 | 88.9 | 0 | 21.4 | 78.6 | 0.0 | 29.4 | 70.5 | 0 |

| Linezolid | 97.9 | 2.1 | 0 | 95.2 | 4.8 | 0 | 94.4 | 5.6 | 0 | 100 | 0.0 | 0 | 96.7 | 3.3 | 0 |

| Daptomycin | 95.7 | 4.3 | 0 | 92.9 | 7.1 | 0 | 77.8 | 22.2 | 0 | 100 | 0.0 | 0 | 92.6 | 7.4 | 0 |

| Vancomycin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Tetracycline | 23.4 | 76.6 | 0 | 40.5 | 59.5 | 0 | 72.2 | 27.8 | 0 | 35.7 | 64.3 | 0 | 38.0 | 62.0 | 0 |

| Tigecycline | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 92.9 | 7.1 | 0 | 99.2 | 0.8 | 0 |

| Nitrofurantoin | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 100 | 0 | 0 |

| Fusidic acid | 12.8 | 87.2 | 0 | 23.8 | 76.2 | 0 | 88.9 | 11.1 | 0 | 7.1 | 92.9 | 0 | 27.3 | 72.7 | 0 |

| Trimethoprim (TMP) | 89.4 | 10.6 | 0 | 85.7 | 14.3 | 0 | 94.4 | 5.6 | 0 | 71.4 | 28.6 | 0 | 86.8 | 13.2 | 0 |

| CoNS Species | No. of Isolates | icaR Positive n (%) | icaA Positive n (%) | icaD Positive n (%) | icaB Positive n (%) | icaC Positive n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. hominis | 47 | 38 (80.85%) | 46 (97.87%) | 21 (44.68%) | 9 (19.14%) | 9 (19.14%) |

| S. epidermidis | 42 | 19 (45.23%) | 42 (100%) | 30 (71.43%) | 22 (52.38%) | 22 (52.38%) |

| S. capitis | 18 | 17 (94.44%) | 18 (100%) | 10 (55.56%) | 1 (5.56%) | 1 (5.56%) |

| S. haemolyticus | 14 | 11 (78.57%) | 14 (100%) | 6 (42.86%) | 3 (21.43%) | 3 (21.43%) |

| Total | 121 | 85 (70.24%) | 120 (99.17%) | 67 (55.37%) | 35 (28.92%) | 35 (28.92%) |

| icaR | icaA | İcaD | icaB | icaC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | −0.875 | 0.091 | 0.898 | 0.875 | 0.875 |

| p | 0.001 | 0.319 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| Antibiotics | Strong Biofilm (n = 35) | Moderate Biofilm (n = 32) | Weak Biofilm (n = 53) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S | R | I | S | R | I | S | R | I | |

| Oxacillin | 8 (22.85%) | 27 (77.14%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (9.37%) | 29 (90.62%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (15.09%) | 45 (84.90%) | 0 (0%) |

| Levofloxacin | 0 (0%) | 22 (62.85%) | 13 (37.14%) | 0 (0%) | 28 (87.50%) | 4 (%12.50%) | 0 (0%) | 41 (77.35%) | 12 (22.64%) |

| Erythromycin | 7 (20%) | 28 (80%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (6.25%) | 30 (93.75%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (15.09%) | 45 (84.90%) | 0 (0%) |

| Clindamycin | 17 (48.57%) | 18 (51.42%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (25%) | 24 (75%) | 0 (0%) | 11 (20.75%) | 42 (79.24%) | 0 (0%) |

| Linezolid | 34 (97.14%) | 1 (2.85%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 50 (94.33%) | 3 (5.66%) | 0 (0%) |

| Daptomycin | 33 (94.28%) | 2 (5.71%) | 0 (0%) | 28 (87.50%) | 4 (12.50%) | 0 (0%) | 50 (94.33%) | 3 (5.66%) | 0 (0%) |

| Vancomycin | 35 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (100%) | 0 (%0) | 0 (0%) | 53 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Tetracycline | 11 (31.42%) | 24 (68.57%) | 0 (0%) | 13 (40.62%) | 19 (59.37%) | 0 (0%) | 22 (41.50%) | 31 (58.49%) | 0 (0%) |

| Tigecycline | 35 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 52 (98.11%) | 1 (1.88%) | 0 (0%) |

| Nitrofurantoin | 35 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 53 (100%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Fusidic acid | 6 (17.14%) | 29 (82.85%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (15.62%) | 27 (84.37%) | 0 (0%) | 8 (15.09%) | 45 (84.90%) | 0 (0%) |

| Trimethoprim (TMP) | 30 (85.71%) | 5 (14.28%) | 0 (0%) | 29 (90.62%) | 3 (9.37%) | 0 (0%) | 45 (84.90%) | 8 (15.09%) | 0 (0%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Erdoğan Deniz, N.; Akkaya, Y.; Kılıç, İ.H. Biofilm Production, Distribution of ica Genes, and Antibiotic Resistance in Clinical Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolates. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1215. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121215

Erdoğan Deniz N, Akkaya Y, Kılıç İH. Biofilm Production, Distribution of ica Genes, and Antibiotic Resistance in Clinical Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolates. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1215. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121215

Chicago/Turabian StyleErdoğan Deniz, Neşe, Yüksel Akkaya, and İbrahim Halil Kılıç. 2025. "Biofilm Production, Distribution of ica Genes, and Antibiotic Resistance in Clinical Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolates" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1215. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121215

APA StyleErdoğan Deniz, N., Akkaya, Y., & Kılıç, İ. H. (2025). Biofilm Production, Distribution of ica Genes, and Antibiotic Resistance in Clinical Coagulase-Negative Staphylococci Isolates. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1215. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121215