Use of Cefiderocol for Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections in Hospital at Home: Multicentric Real-World Experience

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Demographic Data

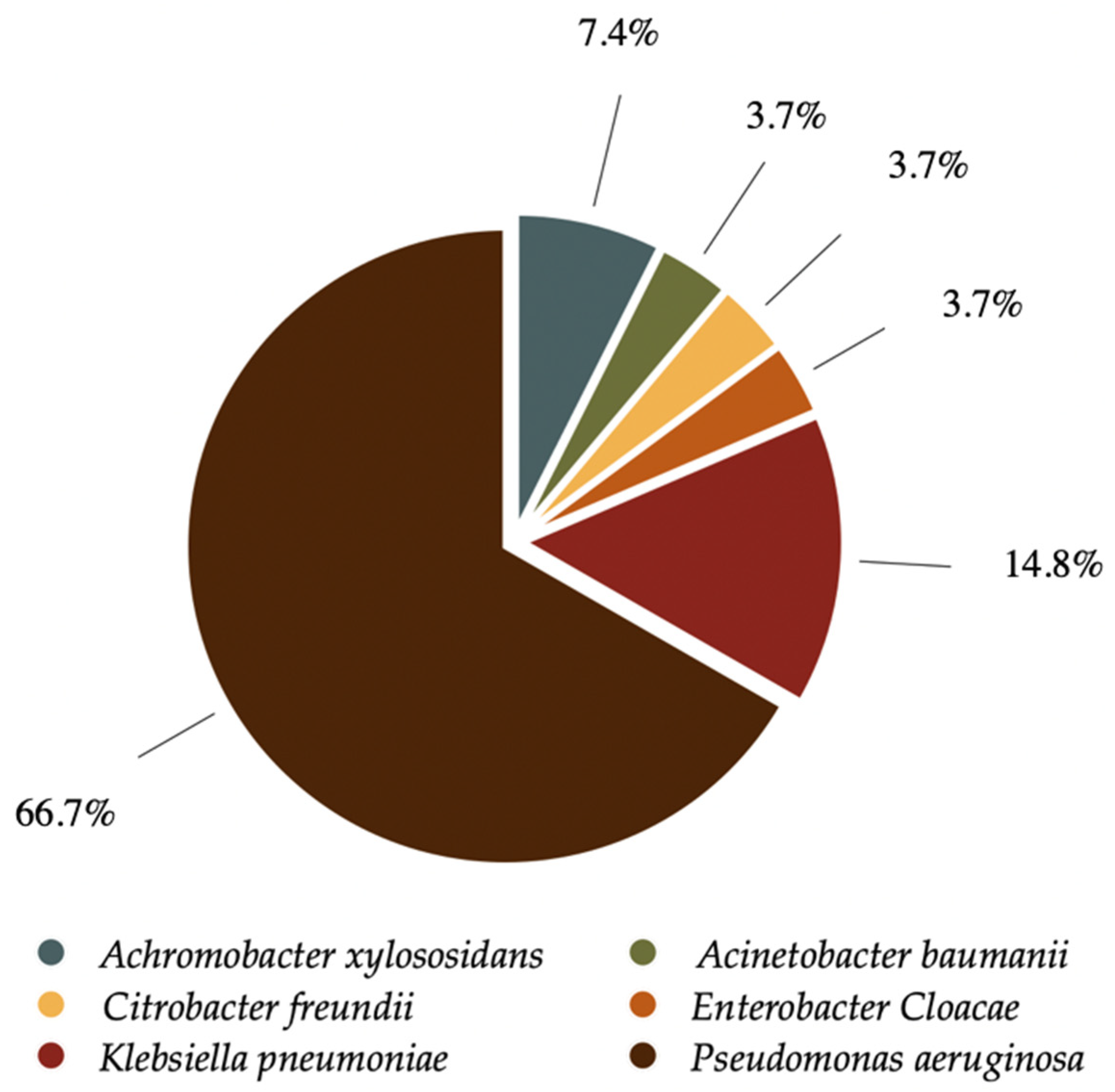

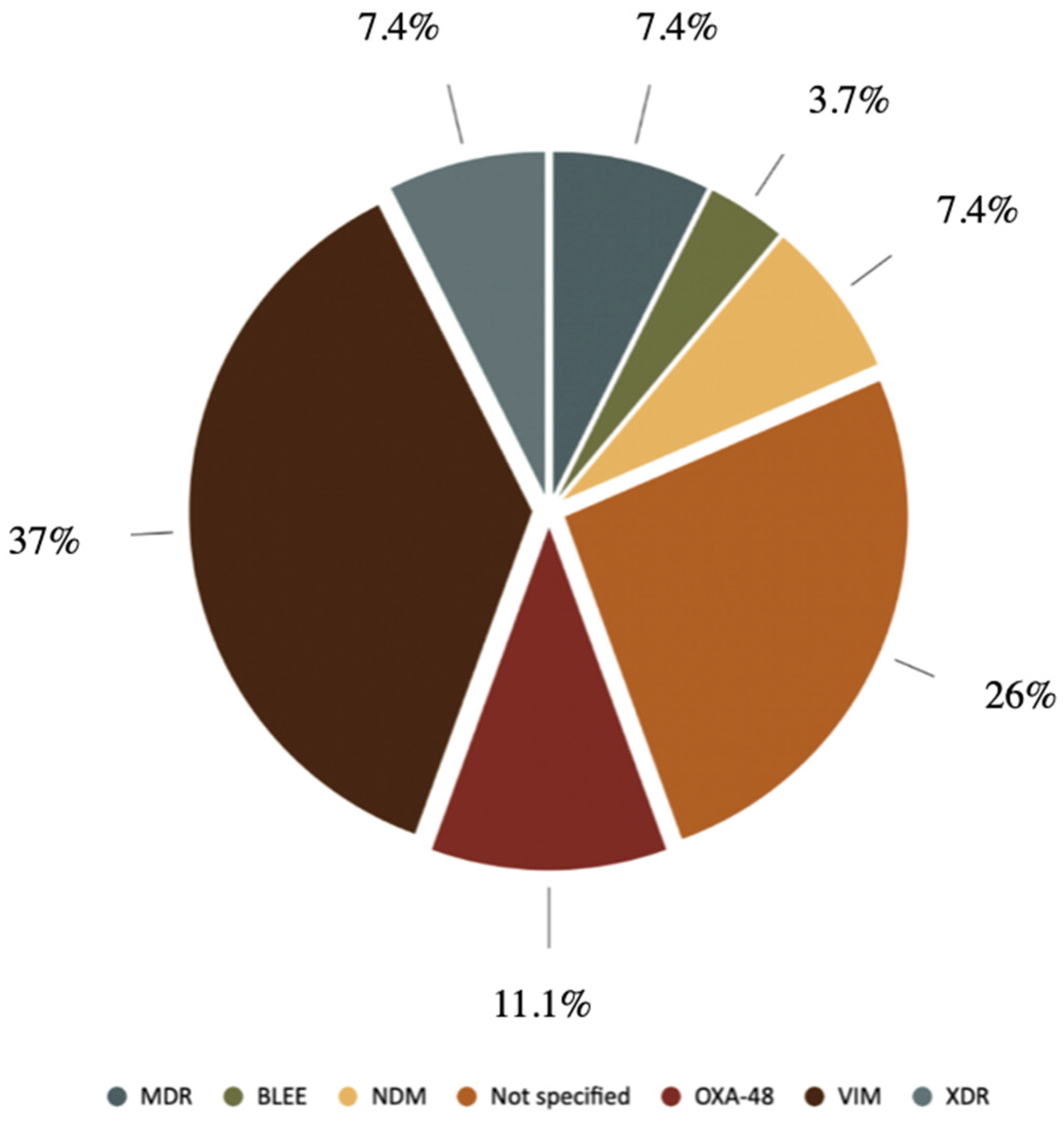

2.2. Microbiology

2.3. Cefiderocol Monitoring and Use

2.4. Safety and Outcomes

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Outcomes and Definitions

4.2. Microbiological Methods

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kohira, N.; West, J.; Ito, A.; Ito-Horiyama, T.; Nakamura, R.; Sato, T.; Rittenhouse, S.; Tsuji, M.; Yamano, Y. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of a Siderophore Cephalosporin, S-649266, against Enterobacteriaceae Clinical Isolates, Including Carbapenem-Resistant Strains. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diarra, A.; Degrendel, M.; Eberl, I.; Ferry, T.; Jaffal, K.; Escaut, L.; Asquier-Khati, A.; Taar, N.; Courjon, J.; Deconinck, L.; et al. Real-Life Cefiderocol Use in Bone and Joint Infection: A French National Cohort. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hackel, M.A.; Tsuji, M.; Yamano, Y.; Echols, R.; Karlowsky, J.A.; Sahm, D.F. In Vitro Activity of the Siderophore Cephalosporin, Cefiderocol, against a Recent Collection of Clinically Relevant Gram-Negative Bacilli from North America and Europe, Including Carbapenem-Nonsusceptible Isolates (SIDERO-WT-2014 Study). Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e00093-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schellong, P.; Wennek-Klose, J.; Spiegel, C.; Rödel, J.; Hagel, S. Successful Outpatient Parenteral Antibiotic Therapy with Cefiderocol for Osteomyelitis Caused by Multi-Drug Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria: A Case Report. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2024, 6, dlae015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, C.J.; Cornely, O.A.; Slover, C.M.; Nguyen, S.T.; Kung, F.H.; Verardi, S.; Longshaw, C.M.; Marcella, S.; Cai, B. Real-World Effectiveness and Safety of Cefiderocol in the Treatment of Patients with Serious Gram-Negative Bacterial Infections: Results of the PROVE Chart Review Study. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2025, 12 (Suppl. S1), ofae631.1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Srinivas, P.; Pogue, J.M. Cefiderocol: A Novel Agent for the Management of Multidrug-Resistant Gram-Negative Organisms. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2020, 9, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreal, C.; Martini, L.; Prataviera, F.; Tascini, C.; Giuliano, S. Antibiotic Stability and Feasibility in Elastomeric Infusion Devices for OPAT: A Review of Current Evidence. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 2722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, G.; Tarantino, D.; Tamburrini, E.; Nurchis, M.C.; Scoppettuolo, G.; Raffaelli, F. Outpatient Parenteral Antibiotic Therapy (OPAT) through Elastomeric Continuous Infusion Pumps in a Real-Life Observational Study: Characteristics, Safety, and Efficacy Analysis. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clin. 2024, 42, 581–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Cortés, L.E.; Mujal Martinez, A.; Fernández Martínez de Mandojana, M.; Martín, N.; Gil Bermejo, M.; Aznar, J.S.; Bruguera, E.V.; Cantero, M.J.P.; González-Ramallo, V.J.; González, M.Á.P.; et al. Resumen Ejecutivo del Tratamiento Antibiótico Domiciliario Endovenoso: Directrices de la Sociedad Española de Enfermedades Infecciosas y la Sociedad Española de Hospitalización a Domicilio. Hosp. Domicilio 2018, 2, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falagas, M.E.; Skalidis, T.; Vardakas, K.Z.; Legakis, N.J. Activity of Cefiderocol (S-649266) against Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Bacteria Collected from Inpatients in Greek Hospitals. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1704–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Roberts, N.; Nicolás, D.; Unwin, S.; Cotta, M.; Roberts, J.A.; Sime, F.B. Implementation of Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy Program in the Contemporary Health Care System: A Narrative Review of the Evidence. J. Infect. Public Health 2025, 18, 102938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasegawa, S.; Tholany, J.; Healy, H.; Suzuki, H. Patient Outcomes Following Home-Based Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy and Facility-Based Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Antimicrob. Steward. Healthc. Epidemiol. 2023, 3, e169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammed, S.A.; Roberts, J.A.; Cotta, M.O.; Rogers, B.; Pollard, J.; Assefa, G.M.; Erku, D.; Sime, F.B. Safety and Efficacy of Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2024, 64, 107263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Fetcroja: EPAR—Product Information. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/fetcroja-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Fernández-Rubio, B.; Herrera-Hidalgo, L.; de Alarcón, A.; Luque-Márquez, R.; López-Cortés, L.E.; Luque, S.; Gutiérrez-Urbón, J.M.; Fernández-Polo, A.; Gutiérrez-Valencia, A.; Gil-Navarro, M.V. Stability Studies of Antipseudomonal Beta Lactam Agents for Outpatient Therapy. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babich, S.; Cojutti, P.G.; Gatti, M.; Pea, F.; Di Bella, S.; Monticelli, J. Feasibility of 24 h Continuous-Infusion Cefiderocol Administered by Elastomeric Pump in Attaining an Aggressive PK/PD Target in the Treatment of NDM-Producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Otomastoiditis. JAC Antimicrob. Resist. 2025, 7, dlaf066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goutelle, S.; Ammour, N.; Ferry, T.; Schramm, F.; Lepeule, R.; Friggeri, A. Optimal dosage regimens of cefiderocol administered by short, prolonged or continuous infusion: A PK/PD simulation study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2025, 80, 726–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ESCMID–European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID); EUCAST. Available online: https://www.eucast.org/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Tamma, P.D.; Heil, E.L.; Justo, J.A.; Mathers, A.J.; Satlin, M.J.; Bonomo, R.A. Infectious Diseases Society of America 2024 Guidance on the Treatment of Antimicrobial-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2024, ciae403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics and Comorbidities (n = 27) | Number, % | |

|---|---|---|

| Patient characteristics | Age, years; median (IQR) | 69 (IQR: 53–80.6) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 8, 29.6% | |

| Male | 19, 70.4% | |

| Charlson comorbidity index; median (IQR) | 3 (IQR: 2.5–7) | |

| Comorbidities | Immunosuppression | 11, 40.7% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10, 37% | |

| Chronic lung disease | 9, 33.3% | |

| Chronic renal failure | 7, 25.9% | |

| Active cancer | 6, 22.2% | |

| Hemiplegia | 5, 18.5% | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4, 14.8% | |

| Referral department | Hospital ward | 20, 74.4% |

| Day-hospital | 4, 14.8% | |

| Primary care | 2, 7.4% | |

| Emergency department | 1, 3.7% |

| Infection Presentation | Number, % | |

|---|---|---|

| Infection acquisition (n = 26) | Nosocomial | 17, 65.4% |

| Community-acquired | 9, 34.6% | |

| Type of infection (n = 27) | Skin and soft tissue infections | 10, 37% |

| Abdominal infections | 6, 22.2% | |

| Urinary tract infections | 5, 18.5% | |

| Respiratory tract infections | 4, 14.8% | |

| Osteoarticular | 2, 7.4% | |

| Microbiological samples (n = 27) | Swabs/Exudates skin and soft tissue lesions | 9, 33.3% |

| Urine culture | 5, 18.5% | |

| Respiratory samples | 4, 14.8% | |

| Blood culture | 3, 11.1% | |

| Peritoneal fluid samples | 2, 7.4% |

| Microorganism | Isolate | Number |

|---|---|---|

| GNB | Achromobacter xylosoxidans | 2 |

| Acinetobacter baumanni | 1 | |

| Citrobacter Freundii | 1 | |

| Enterobacter cloacae | 1 | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 4 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 18 |

| Resistance Mechanism | Number |

|---|---|

| VIM | 10 |

| OXA-48 | 3 |

| NDM | 2 |

| BLEE | 2 |

| KPC | 1 |

| Phenotypic resistance group | Number |

| MDR | 2 |

| XDR | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parra-Plaza, A.; Ugarte, A.; Benavent, E.; García-Poutón, N.; Mujal, A.; Oltra, M.R.; Parra-Rojas, A.; Rico, V.; del Río, M.; Nicolás, D. Use of Cefiderocol for Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections in Hospital at Home: Multicentric Real-World Experience. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121216

Parra-Plaza A, Ugarte A, Benavent E, García-Poutón N, Mujal A, Oltra MR, Parra-Rojas A, Rico V, del Río M, Nicolás D. Use of Cefiderocol for Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections in Hospital at Home: Multicentric Real-World Experience. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121216

Chicago/Turabian StyleParra-Plaza, Andrea, Ainoa Ugarte, Eva Benavent, Nicole García-Poutón, Abel Mujal, María Rosa Oltra, Andrés Parra-Rojas, Verónica Rico, Manuel del Río, and David Nicolás. 2025. "Use of Cefiderocol for Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections in Hospital at Home: Multicentric Real-World Experience" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121216

APA StyleParra-Plaza, A., Ugarte, A., Benavent, E., García-Poutón, N., Mujal, A., Oltra, M. R., Parra-Rojas, A., Rico, V., del Río, M., & Nicolás, D. (2025). Use of Cefiderocol for Carbapenem-Resistant Gram-Negative Infections in Hospital at Home: Multicentric Real-World Experience. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1216. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121216