Tinea capitis in Older Adults: A Neglected and Misdiagnosed Scalp Infection—A Systematic Review of Reported Cases

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

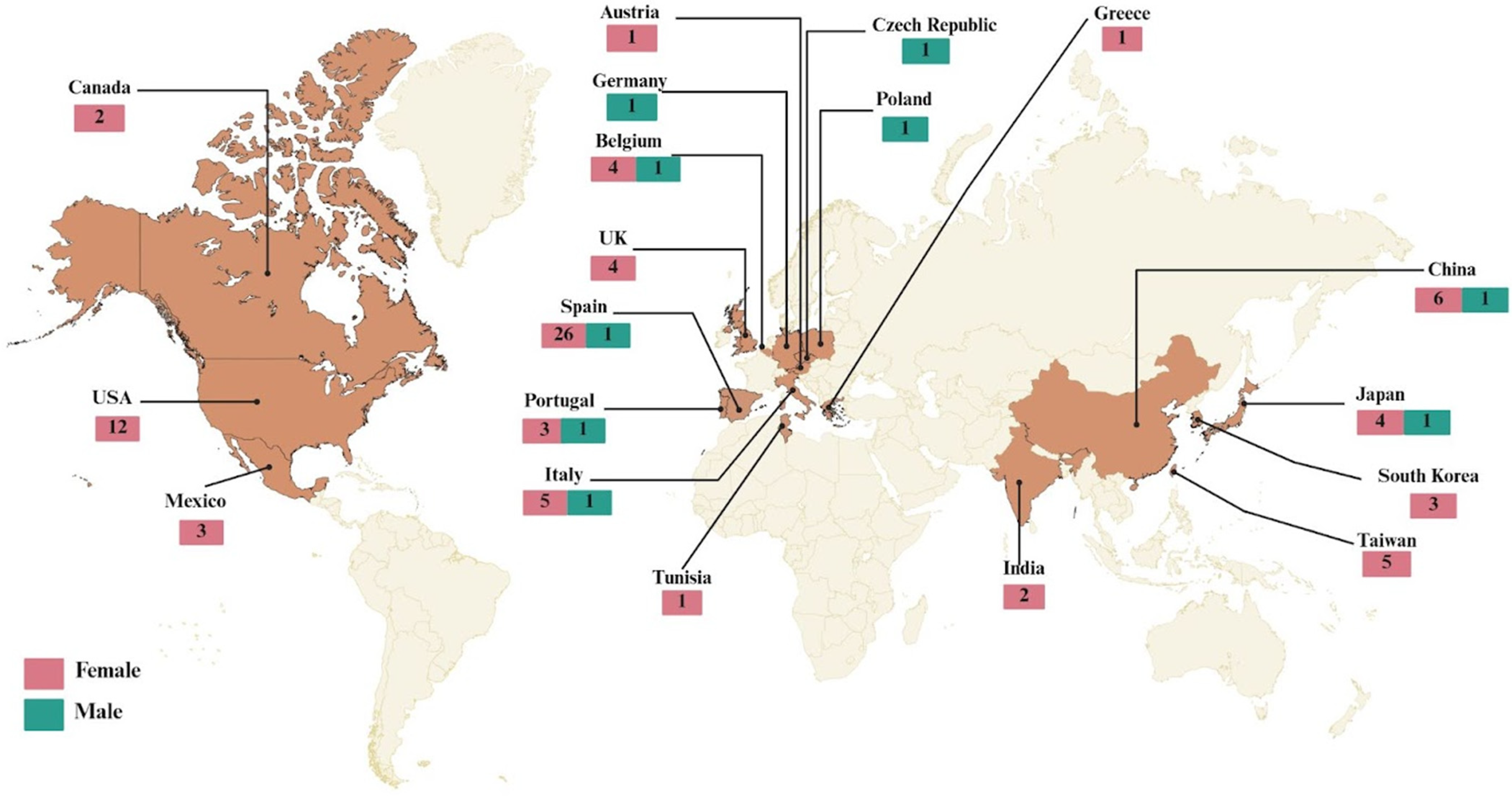

2.1. Demographic and Geographic Characteristics

2.2. Comorbidities and Risk Factors

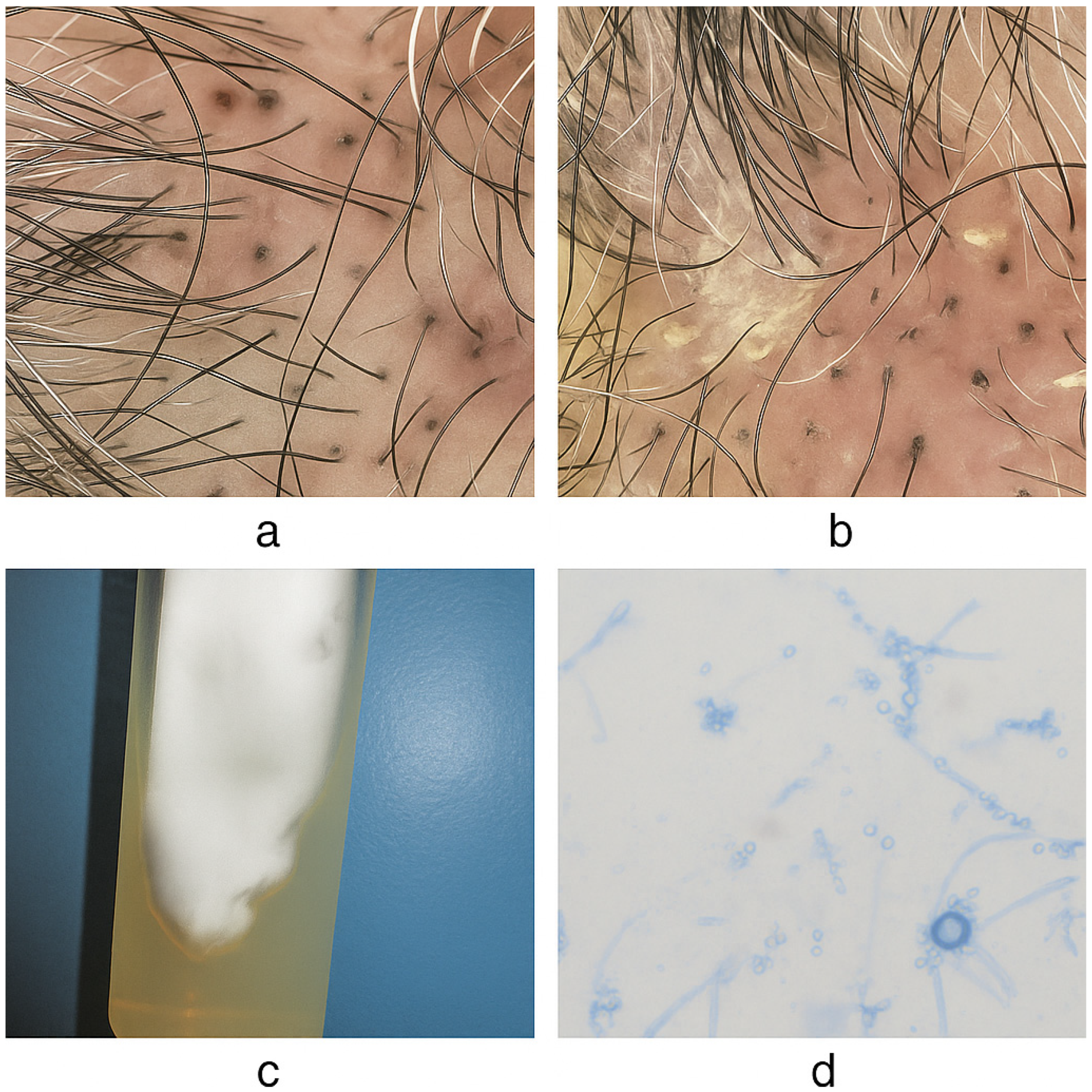

2.3. Clinical Presentation

2.4. Mycological Findings

2.5. Treatment and Management

2.6. Statistical Analyses

3. Discussion

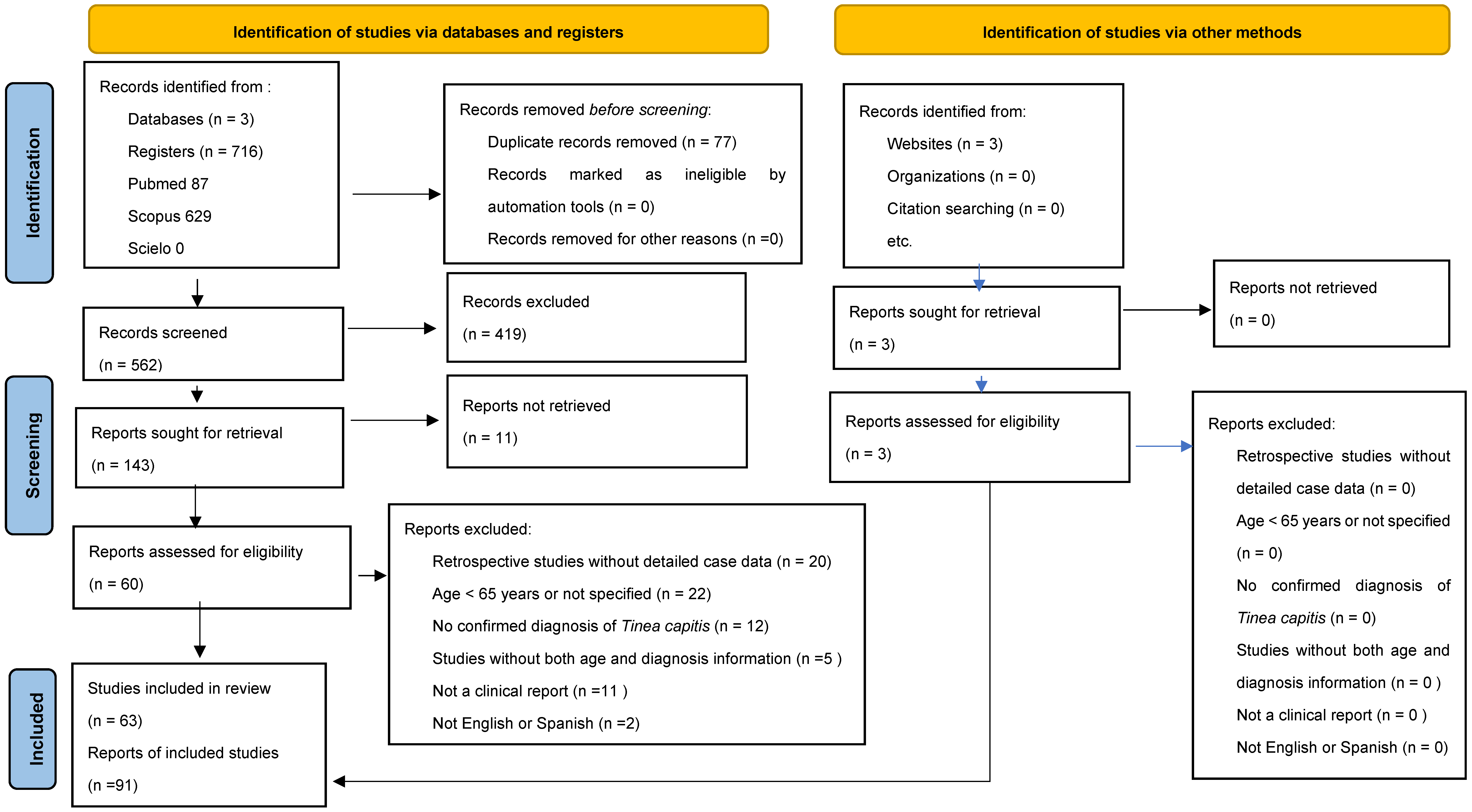

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Quality Assessment

4.2. Statistical Evaluation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Year | Country | Misdiagnosed | Onset (Days) | Elementary Lessions (Onset) | Secondary Lessions (Evolution) | Associated Symptoms | Erythema | Alopecia | Dermoscopy | Pattern (Kerion, Favus, Dry Scalp) | Cure | Scopus Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007 | Austria | Eczema | 60 | Papule | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [20] |

| 1980 | Belgium | No | 60 | Plaque, Pustule | Scale | Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [21] |

| 2014 | No | NA | Pustule | Crust, Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [22] | |

| 2014 | No | NA | None | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [22] | |

| 2014 | No | NA | Papule | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [22] | |

| 2014 | No | NA | Papule | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [22] | |

| 1995 | Canada | No | 42 | Pustule | Scale, Crust | None | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [23] |

| 2000 | Bacterial pyoderma | 90 | Pustule | Crust | None | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [24] | |

| 2021 | Czech Republic | Seborrheic dermatitis, Psoriasis | 180 | Papule | Crust, Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | Yes | [25] |

| 2022 | No | 540 | Pustule | Crust | None | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [26] | |

| 2022 | No | 60 | Plaque | Crust, Scale | Pain, odor | Yes | Yes | No | Favus | Yes | [27] | |

| 2023 | Bacterial infection | 21 | Nodule, Pustule, Plaque | Crust | Pruritus, Fever, Lymphadenopathy, Pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Kerion | Yes | [28] | |

| 2023 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 180 | Papule | Scale, Crust | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | Yes | [29] | |

| 2024 | Erosive Pustular Dermatosis | 90 | Pustule, Nodule | Crust | Pruritus, Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | No | [30] | |

| 2025 | No | 180 | Papule, Pustule, Patch | Ulcer, Crust | Pruritus, Fever, Pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Kerion | Yes | [31] | |

| 2010 | No | 360 | Pustule, Plaque | Crust | Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [32] | |

| 2005 | Germany | Bacterial pyoderma | 42 | Pustule, Nodule | Scale | Pruritus, Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [33] |

| 2011 | Greece | Seborrheic dermatitis | 60 | Pustule | Scale, Crust | None | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [34] |

| 2006 | India | LPP | 720 | Papule, Macule | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [35] |

| 2014 | Bacterial pyoderma | 270 | Pustule, Plaque, Papule | Crust | Pruritus, Pain, Lymphadenopathy | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [36] | |

| 1986 | Italy | No | 360 | Macule | Scale, Crust | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [37] |

| 1995 | No | 60 | Pustule, Macule | Scale | No | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [38] | |

| 2003 | No | 21 | Plaque | Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | Favus | NA | [39] | |

| 2019 | No | NA | Plaque | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | Yes | [40] | |

| 2022 | No | >90 | Papule, Pustule | Crust | Pruritus, Edema | Yes | Yes | Yes | Kerion | Yes | [41] | |

| 1998 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 21 | Papule | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [42] | |

| 1999 | Japan | Perifolliculitis | 90 | Pustule, Abscess | Scale, Crust | Pain, Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [43] |

| 2004 | No | NA | None | Scale | No | No | Yes | No | Dry scalp | No | [44] | |

| 2011 | No | NA | None | Scale | No | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [45] | |

| 2016 | Erosive Pustul Dermatosis | 60 | Pustule, Plaque | Crust, Ulcer | No | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [46] | |

| 2021 | Annular erythema | 360 | None | Scale | No | No | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | Yes | [47] | |

| 2002 | Mexico | No | 3600 | Papule | Scale, Crust | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [48] |

| 2005 | Discoid lupus erythematosus | 375 | Pustule | Scale, Crust | Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [49] | |

| 2015 | No | 1040 | Papule | Scale | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | Yes | [50] | |

| 2024 | Poland | No | 24 | Papule, Pustule | Crust, Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [51] |

| 2019 | Portugal | Erosive Pustular Dermatosis | 90 | Pustule | Crust, Ulcer | Odor, Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | No | [52] |

| 2019 | No | NA | None | None | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [53] | |

| 2019 | No | NA | None | None | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [53] | |

| 2019 | Seborrheic dermatitis | NA | None | None | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [53] | |

| 2020 | South Korea | No | 42 | Patch | Scale | Pain, Pruritus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | Yes | [54] |

| 2022 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 1080 | Patch, Pustule | Crust, Scale, Ulcer | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [55] | |

| 2024 | No | 180 | Pustule, Patch, Papule | Crust, Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | Yes | [56] | |

| 2002 | Spain | Erosive Pustula Dermatosis | 90 | Pustule, Plaque | Crust, Ulcer | Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [57] |

| 2002 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 360 | Pustule, Papule | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [58] | |

| 2004 | Cancer | 1080 | Papule, Pustule | Crust, Scale | No | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [59] | |

| 2004 | No | NA | Papule, Vesicule, Pustule, Patch | Crust | Lymphadenopathy | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [60] | |

| 2006 | No | 150 | None | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [61] | |

| 2007 | No | 180 | Papule | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [62] | |

| 2012 | Eczema | 90 | Pustule | Scale, Crust | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [63] | |

| 2012 | Eczema | 90 | Pustule | Crust | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [63] | |

| 2012 | No | 42 | None | Crust, Ulcer | No | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [63] | |

| 2012 | Bacterial infection | 21 | None | Crust, Ulcer | Lymphadenopathy | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [63] | |

| 2015 | Bacterial pyoderma | 150 | Pustule | Crust | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [64] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Pustule, Papule | Crust, Scale | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2016 | No | NA | Papule, Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | NA | Yes | [5] | |

| 2021 | No | 90 | Pustule | Crust, Ulcer | No | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [65] | |

| 2021 | No | 365 | Plaque | Scale | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | Yes | [66] | |

| 1991 | Taiwan | Seborrheic dermatitis | 7200 | Pustule, None | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [67] |

| 1991 | No | 30 | Pustule, Papule | Scale, Crust | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [67] | |

| 1991 | No | 30 | Pustule, Papule | Scale, Crust | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [67] | |

| 2014 | No | 30 | Papule, Macule | None | Pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | NA | [68] | |

| 2015 | No | 90 | Pustule, Plaque | None | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | NA | [69] | |

| 2012 | Tunisia | No | 3600 | Plaque | Scale, Crust | Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Favus | Yes | [70] |

| 1978 | United Kingdom | No | 360 | Papule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [71] |

| 1994 | Erosive Pustular Dermatosis | 28 | Pustule | Scale, Crust | No | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [72] | |

| 2001 | No | 90 | Pustule | Scale | No | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [73] | |

| 2001 | No | 120 | Pustule, Papule | Scale | Edema | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [73] | |

| 1980 | USA | No | 10 | Pustule, Plaque | Crust, Scale | Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [74] |

| 1993 | Discoid lupus erythematosus | NA | Plaque, Pustule | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | NA | [75] | |

| 2002 | Seborrheic dermatitis | 1800 | None | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | NA | [76] | |

| 2003 | Bacterial pyoderma | 720 | Pustule | Scale, Crust | Pruritus, Pain, Lymphadenopathy | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [77] | |

| 2003 | Bacterial pyoderma | 15 | Pustule | Crust | Lymphadenopathy, Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [77] | |

| 2013 | Erosive Pustular Dermatosis | 90 | Pustule | Scale, Ulcer, Crust | Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [16] | |

| 2013 | Erosive Pustular Dermatosis | 720 | Pustule, Nodule | Scale, Ulcer, Crust | Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [16] | |

| 2013 | Erosive Pustular Dermatosis | 1080 | Pustule, Nodule | Ulcer, Crust | Pain | Yes | Yes | No | Kerion | Yes | [16] | |

| 2014 | No | 90 | Pustule, Nodule | None | Pruritus, Pain | Yes | Yes | Yes | Kerion | Yes | [78] | |

| 2016 | No | 180 | Patch | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | Yes | Dry scalp | Yes | [79] | |

| 2016 | No | 720 | Patch | Scale | Pruritus | Yes | Yes | No | Dry scalp | Yes | [79] | |

| 2016 | No | >90 | Plaque, Nodule | NA | No | Yes | Yes | No | Favus | Yes | [80] |

References

- Hill, R.C.; Gold, J.A.W.; Lipner, S.R. Comprehensive review of Tinea capitis in adults: Epidemiology, risk factors, clinical presentations, and management. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebollo, N.; López-Barcenas, A.P.; Arenas, R. Tiña de la cabeza. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2008, 99, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Ortega, J.I.; Ramirez Cibrian, A.G.; Fernández-Reyna, I.; Atoche Dieguez, C.E. Tinea capitis Kerion Type in Three Siblings Caused by Nannizzia gypsea. Cureus 2024, 16, e55485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.K.; Mays, R.R.; Versteeg, S.G.; Piraccini, B.M.; Shear, N.H.; Piguet, V.; Tosti, A.; Friedlander, S.F. Tinea capitis in children: A systematic review of management. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2018, 32, 2264–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lova-Navarro, M.; Gómez-Moyano, E.; Crespo-Erchiga, V.; Vera-Casano, Á.; Martínez-Pilar, L.; Godoy-Díaz, D.J.; Fernández-Ballesteros, M.D. Tinea capitis in adults in southern Spain: A 17-year epidemiological study. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2016, 33, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, D.; Padilla, M.C.; Fernández, R.; Arenas, R.; Bonifaz, A. Tiña de la cabeza en adultos: Estudio clínico, micológico y epidemiológico de 30 casos en Ciudad de México. Dermatol. Rev. Mex. 2010, 54, 13–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khalawany, M.; Shaaban, D.; Hassan, H.; AbdAlSalam, F.; Eassa, B.; Abdel Kader, A.; Shaheen, I. A multicenter clinicomycological study evaluating the spectrum of adult Tinea capitis in Egypt. Acta Dermatovenerol. Alp. Pannonica Adriat. 2013, 22, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Geng, C.; Blechert, O.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, R.; Luo, Y.; Fan, X.; Qiu, G.; Zhan, P. Neglected adult Tinea capitis in South China: A retrospective study in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, from 2007 to 2021. Mycopathologia 2023, 188, 497–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papa, V.; Farina, A.; Bianchi, L.; Vaccaro, M.; Pioggia, G.; Gangemi, S. Immunosenescence and skin: A state-of-the-art of its modulation for therapeutic purposes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardana, K.; Gupta, A.; Mathachan, S.R. Immunopathogenesis of dermatophytoses and factors leading to recalcitrant infections. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2021, 12, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaul, S.; Yadav, S.; Dogra, S. Treatment of dermatophytosis in elderly, children, and pregnant women. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2017, 8, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainer, B.L. Dermatophyte infections. Am. Fam. Phys. 2003, 67, 101–108. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.Y.; Lo, H.J.; Tu, M.G.; Ju, Y.M.; Fan, Y.C.; Lin, C.C.; Chiang, Y.T.; Yang, Y.L.; Chen, K.T.; Sun, P.L. The survey of Tinea capitis and scalp dermatophyte carriage in nursing home residents. Med. Mycol. 2018, 56, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gahalaut, P.; Mehra, M.; Mishra, N.; Rastogi, M.K.; Bery, V. Clinicoepidemiologic profile of dermatophytosis in the elderly: A hospital based study. Nepal J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2021, 19, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar, E.; Asz-Sigall, D.; Vega, D.; Arenas, R. Tinea capitis: Unusual chronic presentation in an elderly woman. J. Infect. Dis. Epidemiol. 2018, 4, 048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia, C.; Dahl, M.V. Kerion mimicking erosive pustular dermatosis in elderly patients. Cutis 2013, 91, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al Aboud, A.M.; Nigam, P.K. Tinea capitis. StatPearls; 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536909/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Shivanna, R.; Rajesh, G. Management of dermatophytosis in elderly and with systemic comorbidities. Clin. Dermatol. Rev. 2017, 1 (Suppl. S1), S38–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastelan, M.; Prpić Massari, L.; Simonić, E.; Gruber, F. Tinea incognito due to Microsporum canis in a 76-year-old woman. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2007, 119, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hecke, E.; Meysman, L. Tinea capitis in an adult (Microsporum canis). Mykosen 1980, 23, 607–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillary, T.; Suys, E. An outbreak of Tinea capitis in elderly patients. Int. J. Dermatol. 2014, 53, e101–e103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargman, H.; Kane, J.; Baxter, M.L.; Summerbell, R.C. Tinea capitis due to Trichophyton rubrum in adult women. Mycoses 1995, 38, 231–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bargman, H. Trichophyton rubrum Tinea capitis in an 85-year-old woman. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2000, 4, 148–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Chen, W.; Wan, Z.; Li, R.; Yu, J. Tinea capitis by Microsporum canis in an elderly female with extensive dermatophyte infection. Mycopathologia 2021, 186, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.; Zhi, H.; Liu, Z.; Shen, H. Adult kerion caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a vegetarian woman with onychomycosis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2023, 29, 188–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, X.-J.; Zhi, H.-L.; Liu, Z.-H. Revival of generalized favus. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 122, 112–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Xia, X.-J.; Zhi, H.-L.; Liu, Z.-H.; Shen, H. Successful treatment of diffuse pustular inflammatory Tinea capitis in the elderly with repeated debridement, oral terbinafine and short-course steroids. Mycopathologia 2023, 188, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.-L.; Chi, C.-C.; Shih, I.-H.; Fan, Y.-C. Nannizzia polymorpha as Rare Cause of Skin Dermatophytosis. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 1451–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Liang, C.-T.; Zhong, J.-J.; Kong, X.; Xu, H.-X.; Xu, C.-C.; Fu, M.-H. 5-aminolevulinic acid-based photodynamic therapy in combination with antifungal agents for adult kerion and facial ulcer caused by Trichophyton rubrum. Photodiagnosis Photodyn. Ther. 2024, 45, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Dong, B.; Hu, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Li, X.; Wang, H. Adult kerion caused by Trichophyton tonsurans. Mycopathologia 2025, 190, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuklová, I.; Štork, J.; Lacina, L. Trichophyton rubrum suppurative tinea of the bald area of the scalp. Mycoses 2010, 53, 456–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziemer, A.; Kohl, K.; Schröder, G. Trichophyton rubrum-induced inflammatory Tinea capitis in a 63-year-old man. Mycoses 2005, 48, 144–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rallis, E.; Koumantaki-Mathioudaki, E.; Papadogeorgakis, H. Microsporum canis Tinea capitis in a centenarian patient. Indian J. Dermatol. Venereol. Leprol. 2011, 77, 626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avninder, S.; Ramesh, V. A patch of alopecia in a 70-year-old woman. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2007, 32, 275–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, S.M.; Wani, G.H.M.; Khursheed, B. Kerion mimicking bacterial infection in an elderly patient. Indian Dermatol. Online J. 2014, 5, 494–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannini, P.; Guadagni, R.; Palleschi, G.M.; Nisi, C.; Sansoni, M. Tinea capitis in the adult: Two case studies. Mycopathologia 1986, 96, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianni, C.; Betti, R.; Perotta, E.; Crosti, C. Tinea capitis in adults. Mycoses 1995, 38, 329–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cecchi, R.; Paoli, S.; Giomi, A.; Rossetti, R. Favus due to Trichophyton schoenleinii in a patient with metastatic bronchial carcinoma. Br. J. Dermatol. 2003, 148, 1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vastarella, M.; Gallo, L.; Cantelli, M.; Nappa, P.; Fabbrocini, G. An undetected case of Tinea capitis in an elderly woman affected by dermatomyositis: How trichoscopy can guide to the right diagnosis. Ski. Appendage Disord. 2019, 5, 186–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starace, M.; Boling, L.B.; Bruni, F.; Lanzoni, A.; Milan, E.; Pepe, F.; Piraccini, B.M.; Misciali, C. Telogen-sparing arthroconidia involvement in an adult case of endothrix Tinea capitis. J. Egypt. Women’s Dermatol. Soc. 2022, 19, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Offidani, A.; Simoncini, C.; Arzeni, D.; Cellini, A.; Amerio, P.; Scalise, G. Tinea capitis due to Microsporum gypseum in an adult. Mycoses 1998, 41, 239–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanuma, H.; Doi, M.; Abe, M.; Kume, H.; Nishiyama, S.; Katsuoka, K. Kerion Celsi effectively treated with terbinafine: Characteristics of Kerion Celsi in the elderly in Japan. Mycoses 1999, 42, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogasawara, Y.; Hara, J.; Hiruma, M.; Muto, M. A case of black dot ringworm attributable to Trichophyton violaceum: A simple method for identifying macroconidia and microconidia formation by Fungi-Tape™ and MycoPerm-Blue™. J. Dermatol. 2004, 31, 424–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakae, H.; Noguchi, H.; Hattori, M.; Hiruma, M. Observation of micro- and macroconidia in Trichophyton violaceum from a case of Tinea faciei. Mycoses 2011, 54, e656–e658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuragi, Y.; Sawada, Y.; Hara, Y.; Ohmori, S.; Omoto, D.; Haruyama, S.; Yoshioka, M.; Nishio, D.; Nakamura, M. Increased circulating Th17 cell in a patient with Tinea capitis caused by Microsporum canis. Allergol. Int. 2016, 65, 215–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyata, A.; Kimura, U.; Noguchi, H.; Matsumoto, T.; Hiruma, M.; Kano, R.; Takamori, K.; Suga, Y. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton violaceum successfully treated with fosravuconazole. J. Dermatol. 2021, 48, e331–e332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, R.F.; Liébanos, S.; Arenas, R. Tiña de la cabeza recurrente en un adulto (Tinea of the recurrent head in adult). Dermatol. Venez. 2002, 40, 70–73. [Google Scholar]

- Morán Maese, D.; Tarango-Martínez, V.M.; González Treviño, L.A.; Mayorga, J. Tiña de la cabeza en un adulto. A propósito de un caso. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2005, 22, 54–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Morales, M.E.; Valdez-Landrum, P.; García-Valdés, A.; Arenas, R. Brote epidémico intrafamiliar de tiña de la cabeza por Trichophyton tonsurans: Informe de cuatro casos en tres generaciones. Med. Cutan. Iber. Lat. Am. 2015, 43, 217–221. [Google Scholar]

- Jaworek, A.K.; Hałubiec, P.; Krzyściak, P.M.; Wojas-Pelc, A.; Wójkowska-Mach, J.; Szepietowski, J.C. Kerion-like lesions following an autoinoculation event in a patient with chronic onychomycosis—Case report. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2024, 43, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, F.; Batista, M.; Gonçalo, M. Inflammatory Tinea capitis mimicking erosive pustulosis of the scalp. Acta Med. Port. 2019, 32, 746–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duarte, B.; Galhardas, C.; Cabete, J. Adult Tinea capitis and tinea barbae in a tertiary Portuguese hospital: An 11-year audit. Mycoses 2019, 62, 1079–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, T.H.; Kim, W.I.; Cho, M.K.; Whang, K.U.; Kim, S. Tinea capitis and tinea corporis caused by Microsporum canis in an 82-year-old woman: Efficacy of sequence analysis. J. Mycol. Infect. 2020, 25, 17–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.C.; Kim, M.J.; Mun, J.H. Squamous cell carcinoma of the scalp with Tinea capitis and bacterial infection. J. Mycol. Infect. 2022, 27, 89–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.J.; Nam, K.H.; Yun, S.K.; Park, J. Ultraviolet dermoscopy for diagnosis and treatment monitoring of ectothrix Tinea capitis caused by Microsporum canis. J. Mycol. Infect. 2024, 29, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Ramírez, D.; Herrera-Saval, A.; Camacho, F. Tinea capitis inflamatoria por Trichophyton violaceum simulando dermatosis pustulosa erosiva. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2003, 94, 435–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegue Gallego, F.J.; Bernal Ruiz, A.I.; González Nebreda, M.; Blasco Melguizo, J.; Ruiz Villaverde, R.; Delgado Ceballos, F.J.; Delgado Florencio, V. Tinea capitis en el adulto por Trichophyton violaceum: Presentación de un caso. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2002, 19, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Avilés, J.A.; Huerta, M.; Suárez, R.; Lecona, M.; Lázaro, P. Tiña del cuero cabelludo inflamatoria por Microsporum gypseum en un adulto. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2004, 95, 431–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasco Melguizo, J.; Ruiz Villaverde, R.; Delgado Florencio, V.; Buendía Eisman, A. Tinea capitis by Trichophyton violaceum in an immunosuppressed elderly man. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2004, 18, 100–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Prendes, M.L.-E.; Aguado, C.R.; Seral, C.M.; Oliva, N.P. Tinea capitis in the elderly: An unusual situation. Tiña del cuero cabelludo por Microsporum canis en una mujer adulta. Med. Cutan. Iber. Lat. Am. 2006, 34, 239–241. [Google Scholar]

- Benvenuti, F.; Weschenfelder, G.P. Placas alopécicas en un adulto. Piel 2007, 22, 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morell, L.; Fuente, M.J.; Boada, A.; Carrascosa, J.M.; Ferrándiz, C. Tinea capitis en mujeres de edad avanzada: Descripción de cuatro casos. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2011, 102, 323–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Cerdeira, C.; Arenas, R.; Espasandín-Arias, M. Tiña del cuero cabelludo por Microsporum gypseum en una mujer de edad avanzada. Piel 2015, 30, 429–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Campayo, N.; Meilán Sánchez, I.; Martínez Gómez, W.; Fonseca Capdevila, E. Tinea capitis inflamatoria por Trichophyton rubrum. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021, 112, 371–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilas Boas, P.; Hernández-Aragües, I.; Baniandrés-Rodríguez, O. Placa eritemato descamativa. Erythematous scaly plaque. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2021, 112, 169–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.Y.-Y.; Hsu, M.-L. Tinea capitis in adults in southern Taiwan. Int. J. Dermatol. 1991, 30, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-T.; Li, Y.-C. The dermoscopic comma, zigzag, and bar code-like hairs: Markers of fungal infection of the hair follicles. Dermatol. Sin. 2013, 31, 196–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-H.; Lin, Y.-T. Bar code-like hair: Dermoscopic marker of Tinea capitis and tinea of the eyebrow. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2015, 72 (Suppl. S1), S41–S42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaraa, I.; Zaouek, A.; El Euch, D.; Trojjet, S.; Mokni, M.; Ben Osman, A. Tinea capitis favosa in a 73-year-old immunocompetent Tunisian woman. Mycoses 2012, 55, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, C.M. Tinea capitis in an elderly woman. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1979, 4, 247–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derrick, E.K.; Voyce, M.E.; Price, M.L. Trichophyton tonsurans kerion in an elderly woman. Br. J. Dermatol. 1994, 130, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takwale, A.; Agarwal, S.; Holmes, S.C.; Berth-Jones, J. Tinea capitis in two elderly women: Transmission at the hairdresser. Br. J. Dermatol. 2001, 144, 898–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pursley, T.V.; Raimer, S.S. Tinea capitis in the elderly. Int. J. Dermatol. 1980, 19, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiller, M.J.; Rosenthal, S.A.; Weinstein, A.S. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum in a 67-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1993, 29, 279–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, N.B.; Weinberg, J.M.; DeLeo, V.A. Tinea capitis: Focus on African American women. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2002, 46 (Suppl. S2), S120–S124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, E.S.; Elewski, B.E. Tinea capitis in adult women masquerading as bacterial pyoderma. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003, 49, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LaSenna, C.E.; Miteva, M.; Tosti, A. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of kerion. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2016, 30, 446–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auchus, I.C.; Ward, K.M.; Brodell, R.T.; Brents, M.J.; Jackson, J.D. Tinea capitis in adults. Dermatol. Online J. 2016, 22, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, A.S. Tinea capitis caused by Trichophyton rubrum mimicking favus. Cutis 2016, 98, 205–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ginter-Hanselmayer, G.; Seebacher, C.; Smolle, J. Epidemiology of Tinea capitis in Europe: Current state and changing patterns. Mycoses 2007, 50 (Suppl. S2), 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.K.; Park, S.W.; Yun, S.K.; Kim, H.U.; Park, J. Tinea capitis in adults: An 18-year retrospective, single-center study. Mycoses 2019, 62, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Boz-González, J. Tinea capitis: Trends in Spain. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012, 103, 288–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, M.G.; Maibach, H.I. Estrogen and skin: An overview. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 2001, 2, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, M.J. Estrogens and aging skin. Dermatoendocrinol 2013, 5, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ntshingila, S.; Oputu, O.; Arowolo, A.T.; Khumalo, N.P. Androgenetic alopecia: An update. JAAD Int. 2023, 13, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancianti, F.; Nardoni, S.; Corazza, M.; D’Achille, P.; Ponticelli, C. Environmental detection of Microsporum canis in households of infected cats and dogs. J. Feline Med. Surg. 2003, 5, 323–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Labib, A.; Young, A. Skin Manifestations of Diabetes Mellitus. Endotext; 2022. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK481900/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Roy, R.; Zayas, J.; Singh, S.K.; Delgado, K.; Wood, S.J.; Mohamed, M.F.; Frausto, D.M.; Albalawi, Y.A.; Price, T.P.; Estupinian, R.; et al. Overriding impaired FPR chemotaxis signaling in diabetic neutrophil stimulates infection control in murine diabetic wound. eLife 2022, 11, e72071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, R.S.; Titze, J.; Weller, R. Cutaneous control of blood pressure. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2016, 25, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, B.; Yang, J.; Song, Y.; Zhang, D.; Hao, F. Skin Immunosenescence and Type 2 Inflammation: A Mini-Review With an Inflammaging Perspective. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 835675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Lin, Y.; Han, Z.; Huang, X.; Zhou, S.; Wang, S.; Zhou, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, H. Exploring mechanisms of skin aging: Insights for clinicians. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1421858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zouboulis, C.C.; Hoenig, L.J. Skin aging revisited. Clin. Dermatol. 2019, 37, 293–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, X.; Wei, Z.; Zouboulis, C.C.; Ju, Q. Aging in the sebaceous gland. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 10, 909694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shemer, A.; Lyakhovitsky, A.; Kaplan, B.; Kassem, R.; Daniel, R.; Caspi, T.; Galili, E. Diagnostic approach to Tinea capitis with kerion: A retrospective study. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2022, 39, 914–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, R.; Toussaint, S.; Isa-Isa, R. Kerion and dermatophytic granuloma: Mycological and histopathological findings in 19 children with inflammatory Tinea capitis. Int. J. Dermatol. 2006, 45, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajkumar, A.; Britton, P.N. Kerion: A great mimicker. Med. J. Aust. 2022, 216, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aho-Laukkanen, E.; Mäki-Koivisto, V.; Torvikoski, J.; Sinikumpu, S.P.; Huilaja, L.; Junttila, I.S. PCR enables rapid detection of dermatophytes in practice. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e0104924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waśkiel-Burnat, A.; Rakowska, A.; Sikora, M.; Ciechanowicz, P.; Olszewska, M.; Rudnicka, L. Trichoscopy of Tinea capitis: A systematic review. Dermatol. Ther. 2020, 10, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faergemann, J.; Zehender, H.; Denouël, J.; Millerioux, L. Levels of terbinafine in plasma, stratum corneum, dermis-epidermis, sebum, hair, and nails during and after 250 mg daily. Acta Derm. Venereol. 1993, 73, 305–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MDedge/Cutis Editorial Team. Update on diagnosis and treatment of Tinea capitis (adult overview). Cutis/MDedge 2022, 110, 238–240. [Google Scholar]

- Klotz, U. Pharmacokinetics and drug metabolism in the elderly. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2009, 48, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacopetta, D.; Ceramella, J.; Catalano, A.; Scali, E.; Scumaci, D.; Pellegrino, M.; Aquaro, S.; Saturnino, C.; Sinicropi, M.S. CYP enzymes and drug–drug interactions. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, K.; Glasier, A. Interaction between broad-spectrum antibiotics and the combined oral contraceptive pill: A literature review. Contraception 1999, 59, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, R.; Niazi-Ali, S.; McIvor, A.; Kanj, S.S.; Maertens, J.; Bassetti, M.; Levine, D.; Groll, A.H.; Denning, D.W. Triazole antifungal drug interactions—Practical considerations for excellent prescribing. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2024, 79, 1203–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Chen, X.; Zheng, D.; Xiao, Y.; Dong, B.; Cao, C.; Ma, L.; Tong, Z.; Zhu, M.; Liu, Z.; et al. Epidemiologic features and therapeutic strategies of kerion: A nationwide multicentre study. Mycoses 2024, 67, e13751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gkentsidi, T.; Kampouridis, K.; Bakirtzi, K.; Panagopoulou, A.; Lallas, A.; Sotiriou, E. Monitoring the treatment of Tinea capitis with trichoscopy—Are there signs of trichoscopic cure? Dermatol. Pract. Concept. 2024, 14, e2024158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Year | Country | Sex | Age | Risk Factors and Comorbidity | Topography | Another Dermatophytosis | Diagnostic Method | Agent | Treatment | Ref. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Exam | Culture | Histopathology | Oral | Topic | |||||||||

| 2007 | Austria | F | 76 | TCS | Occipital | Tinea corporis | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | Yes | [20] |

| 1980 | Belgium | F | 75 | CA/PE, FM | Occipital | No | + | + | + | M. canis | Yes | No | [21] |

| 2014 | F | 72 | TCS, NH, HS | Parietal | No | NA | + | + | M. canis | Yes | No | [22] | |

| 2014 | M | 90 | HS | NA | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [22] | |

| 2014 | F | 93 | HS, NH | NA | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [22] | |

| 2014 | F | 93 | HS, NH | NA | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [22] | |

| 1995 | Canada | F | 90 | NH | Parietal, Temporal | Tinea unguium | + | - | NA | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [23] |

| 2000 | F | 85 | HTN, AK, HT | Parietal | No | NA | + | NA | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [24] | |

| 2021 | China | F | 71 | DM/PE | Parietal | Tinea unguium, Tinea corporis, Tinea cruris, Tinea faciei, Tinea pedis | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | Yes | [25] |

| 2022 | F | 75 | Maln. | Parietal, Temporal | Tinea unguium, Tinea pedis | + | + | + | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [26] | |

| 2022 | F | 70 | HT | Occipital, Frontal, Parietal, Temporal | Tinea faciei, Tinea corporis | + | + | + | T. schoenleinii | Yes | No | [27] | |

| 2023 | F | 68 | PE | Occipital, Parietal, Frontal | No | + | + | NA | T. mentagrophytes | Yes | Yes | [28] | |

| 2023 | M | 77 | None | Parietal | Tinea pedis, Tinea unguium | + | + | NA | T. rubrum | Yes | Yes | [29] | |

| 2024 | F | 66 | OCS, HD | Parietal, Frontal | No | + | + | + | T. rubrum | Yes | Yes | [30] | |

| 2025 | F | 69 | None | Occipital | No | + | + | + | T. tonsurans | Yes | Yes | [31] | |

| 2010 | Czech Republic | M | 83 | None | Frontal, Parietal | Tinea pedis, Tinea unguium | + | + | + | T. rubrum | Yes | Yes | [32] |

| 2005 | Germany | M | 65 | None | Parietal | No | - | + | - | T. rubrum | Yes | Yes | [33] |

| 2011 | Greece | F | 100 | Gast., Maln. | Frontal, Parietal | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [34] |

| 2006 | India | F | 70 | None | Occipital | No | + | + | + | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [35] |

| 2014 | F | 70 | None | Occipital, Parietal | No | + | + | NA | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [36] | |

| 1986 | Italy | F | 68 | PE | Parietal, Frontal | Tinea faciei | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [37] |

| 1995 | F | 84 | PE, FM | Parietal | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | Yes | [38] | |

| 2003 | M | 87 | CA | Temporal | Tinea faciei | + | + | NA | T. schoenleinii | Yes | No | [39] | |

| 2019 | F | 79 | AID/OCS, TCS, IS, PE | Parietal, Occipital | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | Yes | [40] | |

| 2022 | F | 66 | None | Parietal, Temporal, Frontal | No | NA | + | + | T. tonsurans | Yes | Yes | [41] | |

| 1998 | F | 69 | PE | Parietal | No | NA | + | NA | N. gypsea | Yes | No | [42] | |

| 1999 | Japan | M | 75 | TCS | Temporal, Occipital | Tinea cruris, Tinea pedis, Tinea unguium | NA | + | - | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [43] |

| 2004 | F | 85 | LD/NH | Parietal | Tinea cruris | + | + | NA | T. violaceum | No | Yes | [44] | |

| 2011 | F | 66 | FM | Parietal, Temporal | No | + | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [45] | |

| 2016 | F | 66 | PE, OCS | Occipital | No | NA | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [46] | |

| 2021 | F | 82 | TCS | Temporal | Tinea corporis, Tinea unguium | + | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [47] | |

| 2002 | Mexico | F | 75 | HTN | Parietal | Tinea corporis, Tinea faciei | + | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | Yes | [48] |

| 2005 | F | 67 | DM | Parietal | Tinea faciei | + | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [49] | |

| 2015 | F | 68 | FM | Parietal | No | + | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [50] | |

| 2024 | Poland | M | 75 | None | Occipital | 2 feet 1 hand syndrome, Tinea unguium, Tinea barbae | NA | + | NA | T. rubrum | Yes | Yes | [51] |

| 2019 | Portugal | F | 92 | Inf./TCS | Occipital, Parietal, Temporal, Frontal | No | NA | + | + | M. audouinii | No | No | [52] |

| 2019 | M | 86 | None | NA | No | + | + | NA | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [53] | |

| 2019 | F | 71 | DM, D | NA | Tinea pedis, Tinea unguium | - | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [53] | |

| 2019 | F | 86 | HIV | NA | Tinea faciei | + | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [53] | |

| 2020 | South Korea | F | 82 | DM/PE | Frontal, Parietal | Tinea faciei, Tinea corporis | + | + | + | M. canis | Yes | Yes | [54] |

| 2022 | F | 90 | CA, Inf. | Occipital, Parietal | No | + | NA | - | NA | No | Yes | [55] | |

| 2024 | F | 82 | HTN/PE | Parietal | No | NA | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | Yes | [56] | |

| 2002 | Spain | F | 75 | DM | Occipital, Parietal, Temporal, Frontal | No | - | + | - | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [57] |

| 2002 | F | 70 | HTN/TCS | Frontal, Parietal | No | + | + | + | T. violaceum | Yes | Yes | [58] | |

| 2004 | F | 70 | TCS | Parietal | Tinea corporis | NA | + | + | N. gypsea | Yes | Yes | [59] | |

| 2004 | M | 77 | CA/OCS, IS | Parietal, Temporal, Frontal | Tinea barbae | + | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | Yes | [60] | |

| 2006 | F | 76 | HTN/PE, TCS | Occipital, Parietal | Tinea faciei | NA | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [61] | |

| 2007 | F | 65 | TCS | Parietal | No | + | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | Yes | [62] | |

| 2012 | F | 71 | TCS | Parietal, Occipital | No | + | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [63] | |

| 2012 | F | 65 | HTN DM | Parietal | No | NA | + | - | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [63] | |

| 2012 | F | 69 | None | Occipital | No | NA | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [63] | |

| 2012 | F | 72 | TCS | Parietal, Temporal, Frontal | No | NA | + | + | T. mentagrophytes | Yes | No | [63] | |

| 2015 | F | 84 | PE, TCS | Temporal, Parietal, Frontal | No | NA | + | + | N. gypsea | Yes | No | [64] | |

| 2016 | F | 76 | None | NA | No | - | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 74 | None | NA | No | - | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 75 | None | NA | No | - | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 68 | None | NA | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 70 | None | NA | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 80 | None | NA | No | + | + | NA | N. gypsea | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 75 | None | NA | No | - | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 80 | None | NA | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 71 | None | NA | No | + | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 74 | OCS | NA | Tinea faciei | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 75 | OCS | NA | No | + | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 70 | IS | NA | No | + | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 71 | IS | NA | No | - | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2016 | F | 71 | TCS | NA | No | - | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [5] | |

| 2021 | F | 78 | None | Parietal, Temporal | Tinea unguium, Tinea pedis | + | + | - | T. rubrum | Yes | Yes | [65] | |

| 2021 | F | 73 | AID | Occipital | No | NA | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | No | [66] | |

| 1991 | Taiwan | F | 66 | FM | Parietal | No | + | + | NA | T. violaceum | Yes | No | [67] |

| 1991 | F | 72 | None | Parietal | No | + | + | NA | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [67] | |

| 1991 | F | 70 | OCS | Parietal | No | + | + | NA | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [67] | |

| 2014 | F | 65 | None | Parietal | No | + | - | NA | NA | NA | NA | [68] | |

| 2015 | F | 79 | None | Occipital | Tinea faciei | NA | + | + | M. audouinii | NA | NA | [69] | |

| 2012 | Tunisia | F | 73 | None | Parietal, Temporal, Frontal | Tinea unguium | + | + | NA | T. schoenleinii | Yes | Yes | [70] |

| 1978 | United Kingdom | F | 76 | PE | Frontal | No | NA | + | NA | M. canis | Yes | Yes | [71] |

| 1994 | F | 83 | None | Parietal | No | NA | + | - | T. tonsurans | Yes | Yes | [72] | |

| 2001 | F | 71 | HS | Parietal, Occipital | No | NA | + | + | M. canis | Yes | No | [73] | |

| 2001 | F | 71 | AID/IS, HS | Parietal | No | NA | + | + | M. canis | Yes | No | [73] | |

| 1980 | USA | F | 86 | IHD/FM | Frontal, Occipital | No | + | + | NA | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [74] |

| 1993 | F | 67 | AID/TCS | Parietal | No | + | + | NA | T. rubrum | Yes | Yes | [75] | |

| 2002 | F | 67 | TCS | Parietal | No | + | + | NA | T. tonsurans | NA | NA | [76] | |

| 2003 | F | 87 | PE, OCS | Occipital, Parietal, Temporal | No | NA | + | + | T. tonsurans | Yes | Yes | [77] | |

| 2003 | F | 75 | TCS | Parietal | No | NA | + | - | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [77] | |

| 2013 | F | 84 | AK/TCS | Parietal | No | + | + | - | Trichophyton spp. | Yes | No | [16] | |

| 2013 | F | 75 | AK, CA/TCS, IS | Parietal, Temporal | No | - | + | + | Microsporum spp. | Yes | No | [16] | |

| 2013 | F | 93 | OCS, TCS, IVCS, IS | Parietal, Temporal, Frontal | No | NA | + | + | Microsporum spp. | Yes | Yes | [16] | |

| 2014 | F | 68 | TCS | Parietal | No | - | + | - | Trichophyton spp. | Yes | No | [78] | |

| 2016 | F | 79 | TCS, NH | Parietal | No | NA | + | + | T. tonsurans | Yes | No | [79] | |

| 2016 | F | 72 | PE | Parietal | No | NA | + | + | Microsporum spp. | Yes | No | [79] | |

| 2016 | F | 87 | CA, HTN, Dement. Maln. OA, AK/NH | Parietal | No | NA | + | + | T. rubrum | Yes | No | [80] | |

| Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Total N = 91 | Cured N = 83 | Not Cured N = 8 | x2 | OR | CI 95% | p | OR | CI 95% | p | |

| Sex | Female Male | 82 (100%) 9 (100%) | 75 (91.5%) 8 (88.9%) | 7 (8.5%) 1 (11.1%) | 0.06704 | 1.339 | 0.1067 to 10.42 | 0.7957 | 6.184 | 0.2330 to 113 | 0.2014 |

| Risk Factors | Yes No | 51 (100%) 40 (100%) | 49 (96.1%) 34 (85%) | 2 (3.9%) 6 (15%) | 3.431 | 4.324 | 0.9890 to 21.73 | 0.0640 | 2.140 | 0.1765 to 52.05 | 0.5623 |

| Comorbidity | Yes No | 30 (100%) 61 (100%) | 26 (86.7%) 57 (93.4%) | 4 (13.3%) 4 (6.6%) | 1.152 | 0.4561 | 0.1260 to 1.681 | 0.2832 | 2.712 | 0.2583 to 31.07 | 0.3840 |

| Etiological agent | Trichophyton spp. Other | 56 (100%) 35 (100%) | 51 (91.1%) 32 (91.4%) | 5 (8.9%) 3 (8.6%) | 0.003426 | 0.9563 | 0.2403 to 4.029 | 0.9533 | 0.3782 | 0.01540 to 4.225 | 0.4569 |

| Inflammatory Missing = 5 | Yes No | 43 (100%) 31 (100%) | 39 (90.7%) 27 (87.1%) | 2 (4.7%) 1 (3.2%) | 0.06830 | 0.7222 | 0.04824 to 6.479 | 0.7938 | 2.032 | 0.1892 to 29.09 | 0.5566 |

| Treatment | Yes No | 85 (100%) 6 (100%) | 82 (96.5%) 1 (16.7%) | 3 (3.5%) 5 (83.3%) | 44.51 | 136.7 | 14.88 to 1597 | <0.0001 * | 324.3 | 18.88 to 21,695 | 0.0008 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valdez-Martinez, A.; Santoyo-Alejandre, M.I.; Arenas, R.; Isa-Pimentel, M.A.; Castillo-Cruz, J.; Huerta-Domínguez, K.D.; Soto-Torres, E.F.; Martínez-Herrera, E.; Pinto-Almazán, R. Tinea capitis in Older Adults: A Neglected and Misdiagnosed Scalp Infection—A Systematic Review of Reported Cases. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121211

Valdez-Martinez A, Santoyo-Alejandre MI, Arenas R, Isa-Pimentel MA, Castillo-Cruz J, Huerta-Domínguez KD, Soto-Torres EF, Martínez-Herrera E, Pinto-Almazán R. Tinea capitis in Older Adults: A Neglected and Misdiagnosed Scalp Infection—A Systematic Review of Reported Cases. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121211

Chicago/Turabian StyleValdez-Martinez, Alfredo, Mónica Ingrid Santoyo-Alejandre, Roberto Arenas, Mariel A. Isa-Pimentel, Juan Castillo-Cruz, Karla Daniela Huerta-Domínguez, Erika Fernanda Soto-Torres, Erick Martínez-Herrera, and Rodolfo Pinto-Almazán. 2025. "Tinea capitis in Older Adults: A Neglected and Misdiagnosed Scalp Infection—A Systematic Review of Reported Cases" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121211

APA StyleValdez-Martinez, A., Santoyo-Alejandre, M. I., Arenas, R., Isa-Pimentel, M. A., Castillo-Cruz, J., Huerta-Domínguez, K. D., Soto-Torres, E. F., Martínez-Herrera, E., & Pinto-Almazán, R. (2025). Tinea capitis in Older Adults: A Neglected and Misdiagnosed Scalp Infection—A Systematic Review of Reported Cases. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1211. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121211