Influence of Amoxicillin Dosage and Time of Administration on Postoperative Complications After Impacted Third Molar Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial

Abstract

1. Introduction

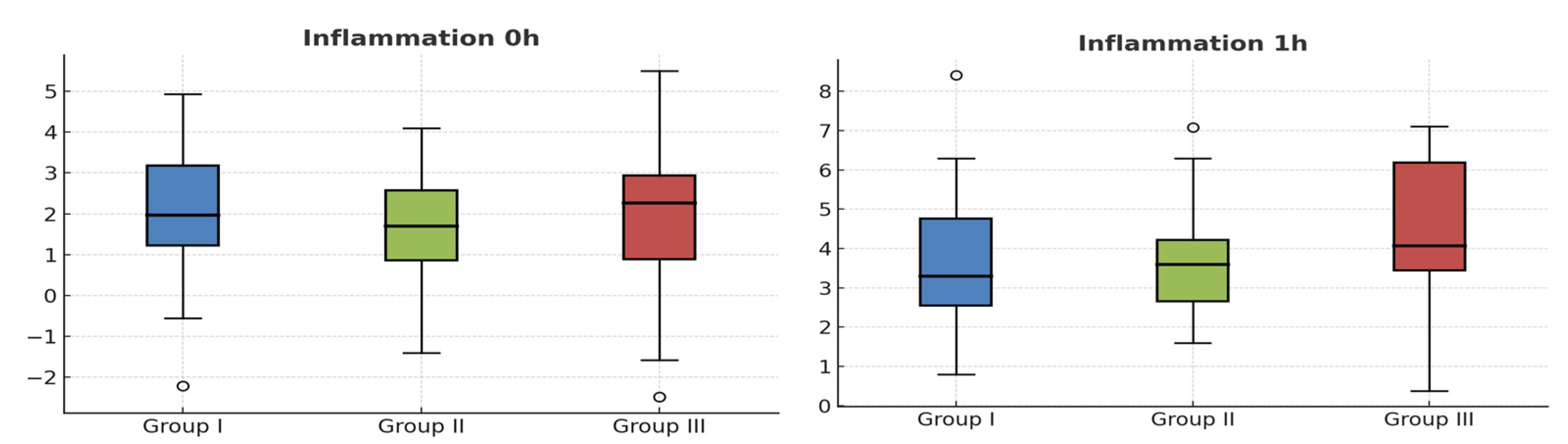

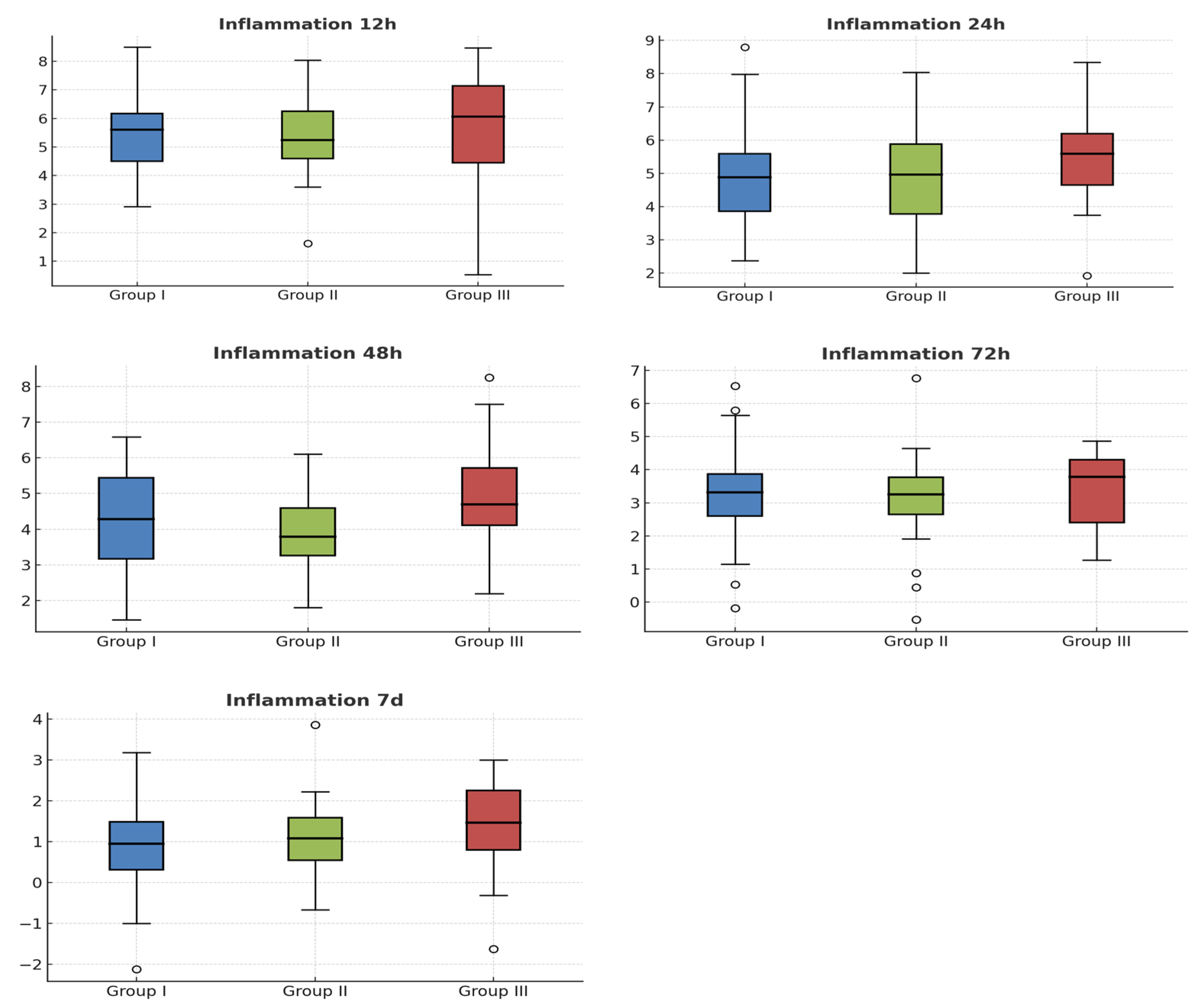

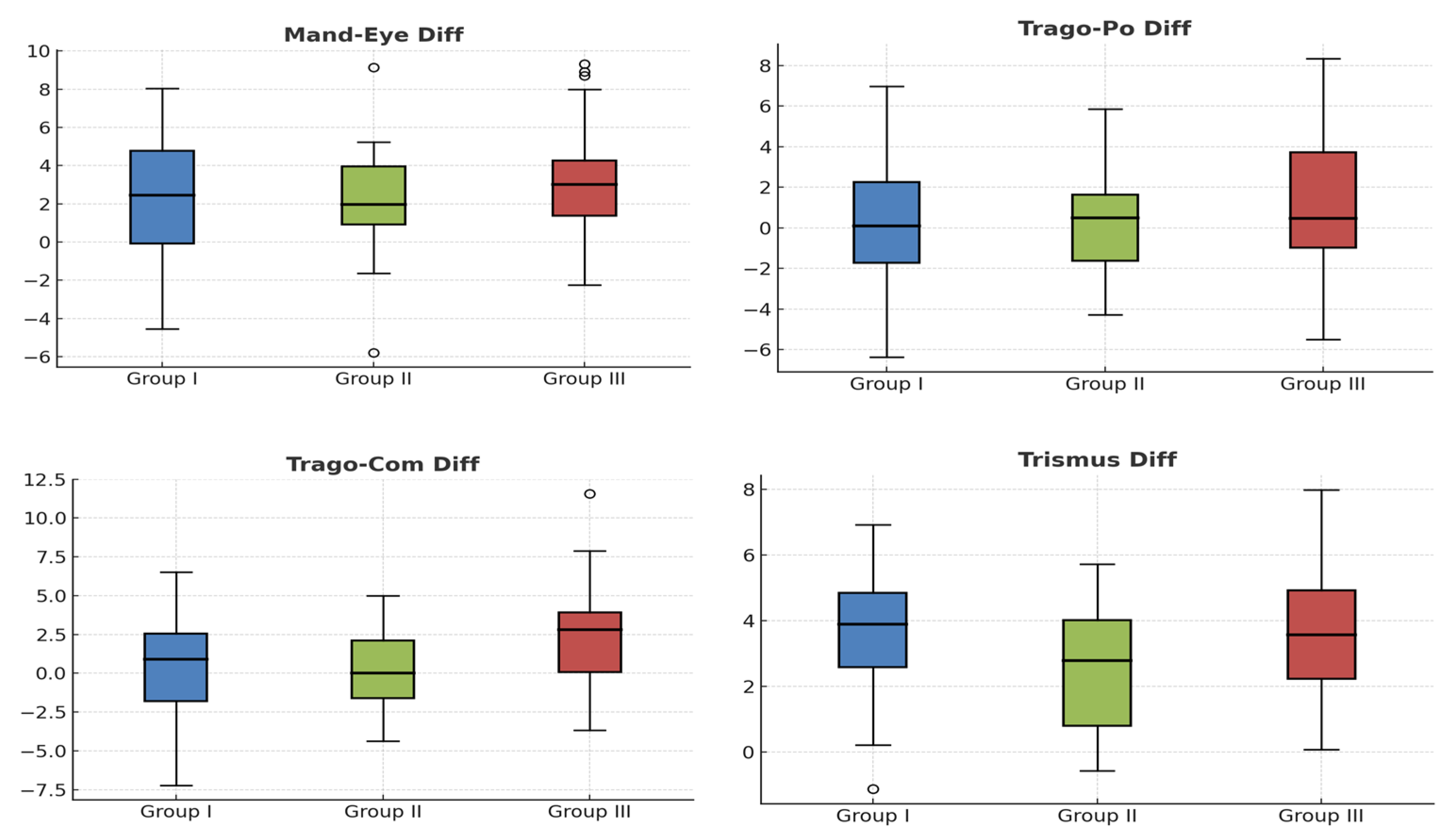

2. Results

Patient Characteristics and Interventions

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design, Patient Selection and Sample Size

4.2. Surgical Protocol

4.3. Study Variables

4.4. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Camps-Font, O.; Sábado-Bundó, H.; Toledano-Serrabona, J.; Valmaseda-de-la-Rosa, N.; Figueiredo, R.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in the Prevention of Dry Socket and Surgical Site Infection after Lower Third Molar Extraction: A Network Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 53, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Angelis, N.; Denegri, L.; Miron, I.C.; Yumang, C.; Pesce, P.; Baldi, D.; Delucchi, F.; Bagnasco, F.; Menini, M. Antibiotic Prescription for the Prevention of Postoperative Complications After Third-Molar Extractions: A Systematic Review. Dent. J. 2025, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, A.; Roychoudhury, A.; Bhutia, O.; Pandey, S.; Singh, S.; Das, B.K. Antibiotics in Third Molar Extraction; Are They Really Necessary: A Non-Inferiority Randomized Controlled Trial. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 5, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torof, E.; Morrissey, H.; Ball, P.A. The Role of Antibiotic Use in Third Molar Tooth Extractions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina 2023, 59, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, U.J. Principles of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.-F.; Malmstrom, H.S. Effectiveness of Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Third Molar Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 1909–1921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raiesian, S.; Ahmadiyeh, A.D.P.; Rad, M.M. A Systematic Review on Prior/Postoperative Antibiotics Therapy Efficiency in Reducing Surgical Complications After Third Molar Extraction Surgery. J. Maxillofac. Oral. Surg. 2025, 24, 1427–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sane, V.D.; Gadre, K.S.; Chandan, S.; Halli, R.; Saddiwal, R.; Kadam, P. Is Post-Operative Antibiotic Therapy Justified for Surgical Removal of Mandibular Third Molar? A Comparative Study. J. Maxillofac. Oral. Surg. 2014, 13, 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aragon-Martinez, O.H.; Isiordia-Espinoza, M.A.; Tejeda Nava, F.J.; Aranda Romo, S. Dental Care Professionals Should Avoid the Administration of Amoxicillin in Healthy Patients During Third Molar Surgery: Is Antibiotic Resistence the Only Problem? J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 1512–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulhane, S.V.; Naphade, M.V.; Gondhalekar, R.; Kolhe, V.; Pande, P.; Sakhare, P.V. Systemic Complications of Use of Antibiotics Following Removal of the Third Molar: A Systematic Review. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2025, 16, 233–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, D.I.; Hughes, D. Persistence of Antibiotic Resistance in Bacterial Populations. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2011, 35, 901–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viola, M.; Quaratino, D.; Gaeta, F.; Valluzzi, R.L.; Caruso, C.; Rumi, G.; Romano, A. Allergic Reactions to Antibiotics, Mainly Betalactams: Facts and Controversies. Eur. Ann. Allergy. Clin. Immunol. 2005, 37, 223–229. [Google Scholar]

- Majid, O.W. Antibiotic Prophylaxis May Effectively Reduce Early Failures after Beginner-Conducted Dental Implant Surgery. Evid. Based. Dent. 2024, 25, 174–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, C.W.; Choe, R.; Chua, S.K.X.; Lum, J.L.; Wang, W.C.-W. Utilising a COM-B Framework to Modify Antibiotic Prescription Behaviours Following Third Molar Surgeries. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2025, 54, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariscal-Cazalla, M.D.M.; Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; García-Vázquez, M.; Vallecillo-Capilla, M.F.; Olmedo-Gaya, M.V. Do Perioperative Antibiotics Reduce Complications of Mandibular Third Molar Removal? A Double-Blind Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. Oral. Surg. Oral. Med. Oral. Pathol. Oral. Radiol. 2021, 131, 286–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bali, A.; Bali, D.; Sharma, A.; Verma, G. Is Pederson Index a True Predictive Difficulty Index for Impacted Mandibular Third Molar Surgery? A Meta-Analysis. J. Maxillofac. Oral. Surg. 2013, 12, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Ares, M.; Barona-Dorado, C.; Martínez-Rodríguez, N.; Cortés-Bretón-Brinkmann, J.; Sanz-Alonso, J.; Martínez-González, J.-M. Does the Postoperative Administration of Antibiotics Reduce the Symptoms of Lower Third Molar Removal? A Randomized Double Blind Clinical Study. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e1015–e1022. [Google Scholar]

- Grønhøj, K.; Søndenbroe, R.; Markvart, M.; Jensen, S.S. Severe Infections after Tooth Removal: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Res. 2025, 16, e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Zhao, C.; Wang, R.; Du, Q.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, J.; Xue, Y.; Han, B.; Jiang, J.; Hu, L.; et al. Postoperative Pain and Influencing Factors after Prophylactic Extraction of Impacted Mandibular Third Molars: A Multicenter Prospective Cohort Study. BMC Oral. Health 2025, 25, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechinger, B.; Gorr, S.-U. Antimicrobial Peptides: Mechanisms of Action and Resistance. J. Dent. Res. 2017, 96, 254–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milani, B.A.; Bauer, H.C.; Sampaio-Filho, H.; Horliana, A.C.R.T.; Perez, F.E.G.; Tortamano, I.P.; Jorge, W.A. Antibiotic Therapy in Fully Impacted Lower Third Molar Surgery: Randomized Three-Arm, Double-Blind, Controlled Trial. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 19, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirnbauer, B.; Jakse, N.; Truschnegg, A.; Dzidic, I.; Mukaddam, K.; Payer, M. Is Perioperative Antibiotic Prophylaxis in the Case of Routine Surgical Removal of the Third Molar Still Justified? A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial with a Split-Mouth Design. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2022, 26, 6409–6421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isiordia-Espinoza, M.A.; Aragon-Martinez, O.H.; Martínez-Morales, J.F.; Zapata-Morales, J.R. Risk of Wound Infection and Safety Profile of Amoxicillin in Healthy Patients Which Required Third Molar Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Br. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 53, 796–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqi, A.; Morkel, J.A.; Zafar, S. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Third Molar Surgery: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Clinical Trial Using Split-Mouth Technique. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2010, 39, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcussen, K.B.; Laulund, A.S.; Jørgensen, H.L.; Pinholt, E.M. A Systematic Review on Effect of Single-Dose Preoperative Antibiotics at Surgical Osteotomy Extraction of Lower Third Molars. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 74, 693–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milic, T.; Raidoo, P.; Gebauer, D. Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery: A Systematic Review. Br. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cedrún, J.L.; Pijoan, J.I.; Fernández, S.; Santamaria, J.; Hernandez, G. Efficacy of Amoxicillin Treatment in Preventing Postoperative Complications in Patients Undergoing Third Molar Surgery: A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind Controlled Study. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 69, e5–e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Liu, X.-G. Efficacy of Amoxicillin or Amoxicillin and Clavulanic Acid in Reducing Infection Rates after Third Molar Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022, 26, 4016–4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falci, S.G.M.; Galvão, E.L.; de Souza, G.M.; Fernandes, I.A.; Souza, M.R.F.; Al-Moraissi, E.A. Do Antibiotics Prevent Infection after Third Molar Surgery? A Network Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 51, 1226–1236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arteagoitia, M.-I.; Barbier, L.; Santamaría, J.; Santamaría, G.; Ramos, E. Efficacy of Amoxicillin and Amoxicillin/Clavulanic Acid in the Prevention of Infection and Dry Socket after Third Molar Extraction. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Med. Oral. Patol. Oral. Cir. Bucal. 2016, 21, e494–e504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dohmen, P.M. Antibiotic Resistance in Common Pathogens Reinforces the Need to Minimise Surgical Site Infections. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008, 70 (Suppl. 2), 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratzler, D.W.; Houck, P.M. Surgical Infection Prevention Guideline Writers Workgroup Antimicrobial Prophylaxis for Surgery: An Advisory Statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Am. J. Surg. 2005, 189, 395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, O.W. Prophylactic Antibiotic Use in Lower Third Molar Surgery May Reduce Dry Socket and Infections, but Evidence Remains Weak. J. Evid. Based. Dent. Pract. 2025, 25, 102128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.W.; Ng, Y.E.; Giok, K.C.; Veettil, S.K.; Menon, R.K. Comparative Efficacy of Different Amoxicillin Dosing Regimens in Preventing Early Implant Failure-A Systematic Review with Network Meta-Analysis. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez Sánchez, F.; Arteagoitia, I.; Teughels, W.; Rodríguez Andrés, C.; Quirynen, M. Antibiotic Dosage Prescribed in Oral Implant Surgery: A Meta-Analysis of Cross-Sectional Surveys. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karemore, T.V.; Ashtankar, K.A.; Motwani, M. Comparative Efficacy of Pre-Operative and Post-Operative Administration of Amoxicillin in Third Molar Extraction Surgery—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2024, 15, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graziani, F.; Corsi, L.; Fornai, M.; Antonioli, L.; Tonelli, M.; Cei, S.; Colucci, R.; Blandizzi, C.; Gabriele, M.; Del Tacca, M. Clinical Evaluation of Piroxicam-FDDF and Azithromycin in the Prevention of Complications Associated with Impacted Lower Third Molar Extraction. Pharmacol. Res. 2005, 52, 485–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergdahl, M.; Hedström, L. Metronidazole for the Prevention of Dry Socket after Removal of Partially Impacted Mandibular Third Molar: A Randomised Controlled Trial. Br. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2004, 42, 555–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaczmarzyk, T.; Wichlinski, J.; Stypulkowska, J.; Zaleska, M.; Panas, M.; Woron, J. Single-Dose and Multi-Dose Clindamycin Therapy Fails to Demonstrate Efficacy in Preventing Infectious and Inflammatory Complications in Third Molar Surgery. Int. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 36, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, L.R.; Dodson, T.B. Does Prophylactic Administration of Systemic Antibiotics Prevent Postoperative Inflammatory Complications after Third Molar Surgery? J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 65, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittes, J. Sample Size Calculations for Randomized Controlled Trials. Epidemiol. Rev. 2002, 24, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell, S.; Chan, A.-W.; Collins, G.S.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Moher, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Tunn, R.; Aggarwal, R.; Berkwits, M.; Berlin, J.A.; et al. CONSORT 2025 Statement: Updated Guideline for Reporting Randomised Trials. BMJ 2025, 389, e081123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabka, J.; Matsumura, T. Measuring techniques and clinical testing of an anti-inflammatory agent (tantum). Munch. Med. Wochenschr. 1971, 113, 198–203. [Google Scholar]

| Characteristic | Group 1 (n = 27) | Group 2 (n = 27) | Group 3 (n = 26) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 0.245 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 25.2 ± 4.1 | 24.8 ± 3.9 | 26.3 ± 4.5 | |

| Median | 25.0 | 24.5 | 26.0 | |

| IQR | [22.0–28.0] | [22.0–27.0] | [23.0–29.0] | |

| Sex (M/F) | 16/14 | 13/11 | 14/12 | 0.991 |

| Oral Hygiene (1–2) | 0.834 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.5 | |

| Median | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| IQR | [1.0–1.0] | [1.0–1.0] | [1.0–1.0] | |

| Smoking Status | 3 (10.0%) | 2 (8.3%) | 4 (15.4%) | 0.721 |

| Presence of EP | 4 (13.3%) | 3 (12.5%) | 5 (19.2%) | 0.689 |

| Pedersen Scale | 0.067 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 5.4 ± 1.2 | 5.3 ± 1.1 | 5.9 ± 1.3 | |

| Median | 5.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 | |

| IQR | [5.0–6.0] | [5.0–6.0] | [5.0–7.0] | |

| Tooth Position | 0.218 | |||

| 16 (60%) | 11 (40%) | 13 (50%) | |

| 11 (40%) | 16 (60%) | 13 (50%) | |

| Angulation (Winter’s) | 0.032 * | |||

| 12 (44.4%) | 6 (22.2%) | 8 (30.8%) | |

| 8 (29.6%) | 11 (40.74%) | 7 (26.9%) | |

| 7 (25.92%) | 10 (37.03%) | 11 (42.3%) | |

| Pell & Gregory Class | 0.175 | |||

| 15 (55.5%) | 12 (44.4%) | 16 (61.5%) | |

| 12 (44.4%) | 15 (55.5%) | 10 (38.5%) | |

| Operative Time (min) | 0.012 * | |||

| Mean ± SD | 36.8 ± 12.4 | 34.2 ± 11.8 | 46.5 ± 13.2 | |

| Median | 35.0 | 32.5 | 45.0 | |

| IQR | [25.0–45.0] | [22.5–42.5] | [35.0–55.0] | |

| Incision Type (1–2) | 0.067 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 1.4 ± 0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.1 ± 0.3 | |

| Median | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |

| IQR | [1.0–2.0] | [1.0–1.0] | [1.0–1.0] | |

| Osteotomy | 0.234 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 2.4 ± 1.1 | |

| Median | 2.0 | 2.0 | 3.0 | |

| IQR | [2.0–3.0] | [2.0–2.0] | [2.0–3.0] | |

| Odontosection | 8 (26.7%) | 6 (25.0%) | 9 (34.6%) | 0.678 |

| Number of Sutures | 0.156 | |||

| Mean ± SD | 3.8 ± 1.1 | 3.7 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 0.9 | |

| Median | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.0 | |

| IQR | [3.0–4.0] | [3.0–4.0] | [3.0–4.0] | |

| Periosteal Tear | 2 (6.7%) | 1 (4.2%) | 3 (11.5%) | 0.589 |

| Group | No Infection [n (%)] | Infection [n (%)] | No Rescue [n (%)] | Rescue [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (n = 27) | 25 (92.5) | 2 (7.5) | 28 (93.3) | 2 (6.7) |

| 2 (n = 27) | 25 (92.5) | 2 (7.5) | 22 (91.7) | 2 (8.3) |

| 3 (n = 26) | 24 (92.3) | 2 (7.7) | 22 (84.6) | 4 (15.4) |

| p-value | 0.412 | 0.287 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valverde-Martínez, P.; Olmedo-Gaya, M.V.; Castro-Gaspar, C.; Ocaña-Peinado, F.M.; Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; Reyes-Botella, C. Influence of Amoxicillin Dosage and Time of Administration on Postoperative Complications After Impacted Third Molar Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121209

Valverde-Martínez P, Olmedo-Gaya MV, Castro-Gaspar C, Ocaña-Peinado FM, Manzano-Moreno FJ, Reyes-Botella C. Influence of Amoxicillin Dosage and Time of Administration on Postoperative Complications After Impacted Third Molar Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121209

Chicago/Turabian StyleValverde-Martínez, Pablo, Maria Victoria Olmedo-Gaya, Carlota Castro-Gaspar, Francisco Manuel Ocaña-Peinado, Francisco Javier Manzano-Moreno, and Candela Reyes-Botella. 2025. "Influence of Amoxicillin Dosage and Time of Administration on Postoperative Complications After Impacted Third Molar Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121209

APA StyleValverde-Martínez, P., Olmedo-Gaya, M. V., Castro-Gaspar, C., Ocaña-Peinado, F. M., Manzano-Moreno, F. J., & Reyes-Botella, C. (2025). Influence of Amoxicillin Dosage and Time of Administration on Postoperative Complications After Impacted Third Molar Surgery: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled Clinical Trial. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1209. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121209