Risk Factors and Outcomes for Invasive Infection Among Patients Colonized with Candidozyma auris: A Case–Control Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

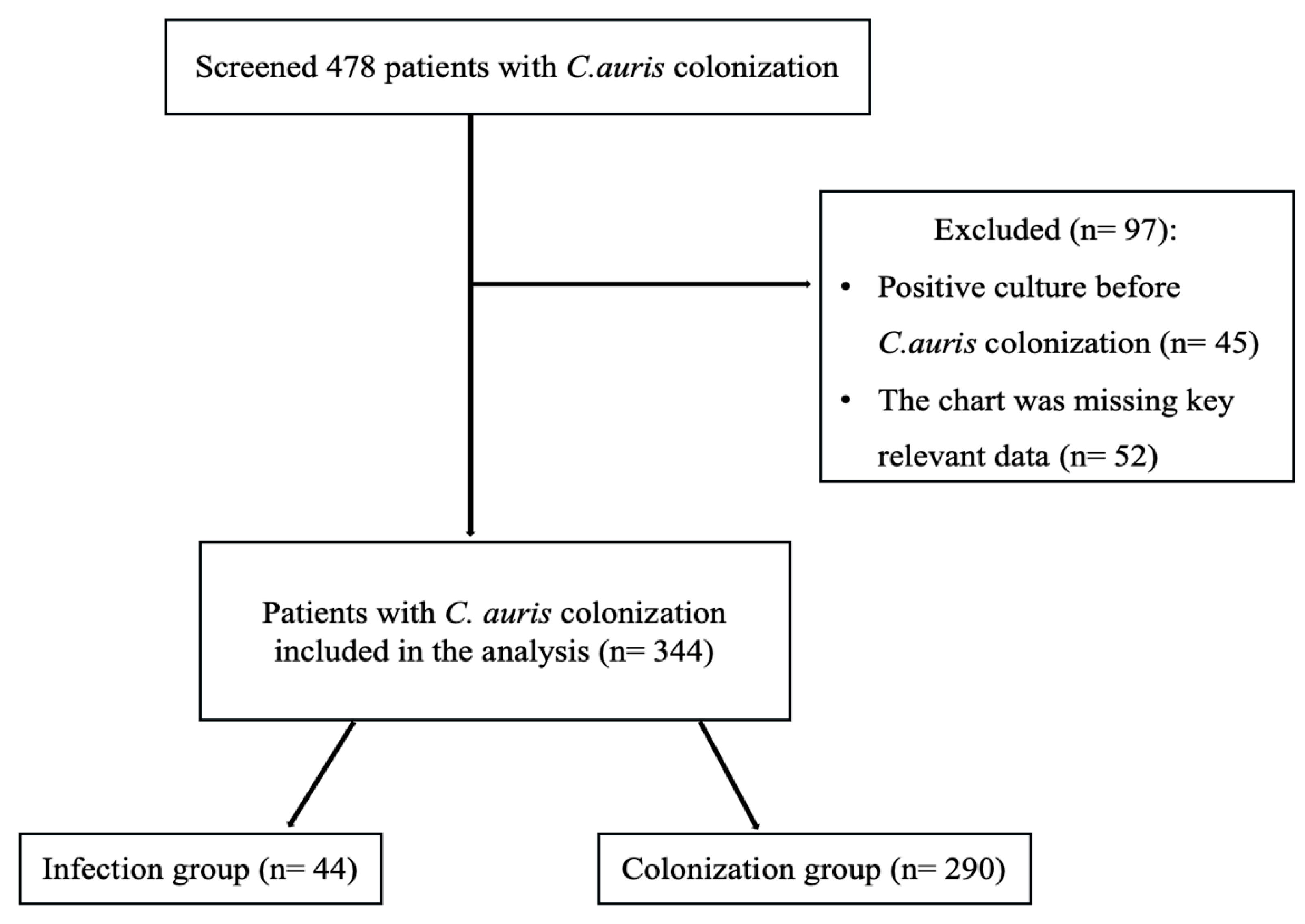

2.1. Study Population and Baseline Characteristics

2.2. Microbiologic and Temporal Characteristics of C. auris Infection

2.3. Treatment and Outcomes Post C. auris Colonization

2.4. Risk Factors for Progression from Colonization to Infection

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Design and Setting

4.2. Ethical Approval

4.3. Definitions

4.4. Outcome Measures

4.5. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Satoh, K.; Makimura, K.; Hasumi, Y.; Nishiyama, Y.; Uchida, K.; Yamaguchi, H. Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol. Immunol. 2009, 53, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osei Sekyere, J. Candida auris: A systematic review and meta-analysis of current updates on an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen. MicrobiologyOpen 2018, 7, e00578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.Y.; Nguyen, T.A.; Kidd, S.; Chambers, J.; Alastruey-Izquierdo, A.; Shin, J.H.; Dao, A.; Forastiero, A.; Wahyuningsih, R.; Chakrabarti, A.; et al. Candida auris: A systematic review to inform the World Health Organization fungal priority pathogens list. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tracking C. Auris [Internet]. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/candida-auris/tracking-c-auris/index.html (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Introduction and Background [Internet]. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/candida-auris-laboratory-investigation-management-and-infection-prevention-and-control/introduction-and-background (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Guan, Q.; Alasmari, F.; Li, C.; Mfarrej, S.; Mukahal, M.; Arold, S.T.; AlMutairi, T.S.; Pain, A. Independent introductions and nosocomial transmission of Candida auris in Saudi Arabia: A genomic epidemiological study of an outbreak from a hospital in Riyadh. Microbiol. Spectr. 2025, 13, e0326024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalhamid, B.; Almaghrabi, R.; Althawadi, S.; Omrani, A.S. First report of Candida auris infections from Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 598–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsawy, A.; Alquthami, K.; Alkhutani, N.; Marwan, D.; Abbas, A. The second confirmed case of Candida auris from Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 907–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jindan, R.; Al-Eraky, D.M. Two cases of the emerging Candida auris in a university hospital from Saudi Arabia. Saudi J. Med. Med. Sci. 2021, 9, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, N.A.; de Groot, T.; Badali, H.; Abastabar, M.; Chiller, T.M.; Meis, J.F. Potential Fifth Clade of Candida auris, Iran, 2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019, 25, 1780–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sikora, A. Candida auris [Internet]; U.S. National Library of Medicine: Bethesda, BA, USA, 2023. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK563297/ (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Ostrowsky, B.; Greenko, J.; Adams, E.; Quinn, M.; O’Brien, B.; Chaturvedi, V.; Berkow, E.; Vallabhaneni, S.; Forsberg, K.; Chaturvedi, S.; et al. Candida auris Isolates Resistant to Three Classes of Antifungal Medications—New York, 2019. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2020, 69, 6–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademe, M.; Girma, F. Candida auris: From multidrug resistance to pan-resistant strains. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 1287–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidance for Detection of C. auris Colonization. CDC Website. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/candida-auris/hcp/laboratories/detection-colonization.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Biswal, M.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Jain, N.; Shamanth, A.S.; Sharma, D.; Jain, K.; Yaddanapudi, L.N.; Chakrabarti, A. Controlling a possible outbreak of Candida auris infection: Lessons learnt from multiple interventions. J. Hosp. Infect. 2017, 97, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossow, J.; Ostrowsky, B.; Adams, E.; Greenko, J.; McDonald, R.; Vallabhaneni, S.; Forsberg, K.; Perez, S.; Lucas, T.; Alroy, K.A.; et al. Factors Associated with Candida auris Colonization and Transmission in Skilled Nursing Facilities with Ventilator Units, New York, 2016–2018. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 72, e753–e760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention of Invasive Infections. CDC; n.d. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/candida-auris/hcp/infection-control/invasive-infection-prevention.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Schelenz, S.; Hagen, F.; Rhodes, J.L.; Abdolrasouli, A.; Chowdhary, A.; Hall, A.; Ryan, L.; Shackleton, J.; Trimlett, R.; Meis, J.F.; et al. First hospital outbreak of the globally emerging Candida auris in a European hospital. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2016, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southwick, K.; Adams, E.H.; Greenko, J.; Ostrowsky, B.; Fernandez, R.; Patel, R.; Quinn, M.; Vallabhaneni, S.; Denis, R.J.; Erazo, R.; et al. New York State 2016–2018: Progression from Candida auris Colonization to Bloodstream Infection. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2018, 5 (Suppl. 1), S594–S595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briano, F.; Magnasco, L.; Sepulcri, C.; Dettori, S.; Dentone, C.; Mikulska, M.; Ball, L.; Vena, A.; Robba, C.; Patroniti, N.; et al. Candida auris candidemia in critically ill, colonized patients: Cumulative incidence and risk factors. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2022, 11, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing the Spread of C. auris [Internet]. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/candida-auris/prevention/index.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Thatchanamoorthy, N.; Rukumani Devi, V.; Chandramathi, S.; Tay, S.T. Candida auris: A Mini Review on Epidemiology in healthcare facilities in Asia. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kordalewska, M.; Zhao, Y.; Lockhart, S.R.; Chowdhary, A.; Berrio, I.; Perlin, D.S. Rapid and Accurate Molecular Identification of the Emerging Multidrug-Resistant Pathogen. J.Clin. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 2445–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhary, A.; Sharma, C.; Meis, J.F. Candida auris: A rapidly emerging cause of hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant fungal infections globally. PLOS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulet Bayona, J.V.; Tormo Palop, N.; Salvador García, C.; Guna Serrano, M.D.; Gimeno Cardona, C. Candida auris from colonisation to Candidemia: A four-year study. Mycoses 2023, 66, 882–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, H.; Hong, D.; Oh, H. Candida auris: Understanding the dynamics of C. auris infection versus colonization. Med. Mycol. 2024, 62, myae086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Marinkovic, A.; Abbasi, A.F.; Prakash, S.; Mangat, J.; Hosein, Z.; Haider, N.; Chan, J. Candida auris: An overview of the emerging drug-resistant fungal infection. Infect. Chemother. 2022, 54, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eix, E.F.; Nett, J.E. Candida auris: Epidemiology and antifungal strategy. Annu. Rev. Med. 2025, 76, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alanazi, K.H.; Roushdy, H.M.; ALzubaidi, W.I.; Alanazi, A.S.; Alanazi, N.M.; Alamri, A.H.; Alnshbah, Y.I.; AL Almatrafi, N.M.; Al Shahrani, Z.M.; Alshanbari, N.H. An overview of healthcare-associated Candida auris outbreaks in Ministry of Health Hospitals–saudi arabia 2020–2022; retrospective multicentric study. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0313589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, M.V.; Holt, A.M.; Nett, J.E. Mechanisms of pathogenicity for the emerging fungus Candida auris. PLOS Pathog. 2023, 19, e1011843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egger, N.B.; Kainz, K.; Schulze, A.; Bauer, M.A.; Madeo, F.; Carmona-Gutierrez, D. The rise of Candida auris: From unique traits to co-infection potential. Microb. Cell 2022, 9, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakumar, A.; Das, D.; Datta, A.; Mishra, A.; Bryak, G.; Ganesh, S.M.; Netea, M.G.; Kumar, V.; Lionakis, M.S.; Arora, D.; et al. Single-cell transcriptomics unveils skin cell specific antifungal immune responses and IL-1ra- il-1r immune evasion strategies of emerging fungal pathogen Candida auris. PLoS Pathog. 2024, 20, e1012699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshahrani, F.; Elgujja, A.; Alsubaie, S.; Ezreqat, S.; Albarrag, A.; Barry, M.; Binkhamis, K.; Alabdan, L.; Bugshan, H.S.; Ledesma, D.R.; et al. Risk factors for Candidozyma auris among admitted patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia (2020–2022). Infect. Drug Resist. 2025, 18, 3369–3381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo, B.; Melo, A.S.A.; Perozo-Mena, A.; Hernandez, M.; Francisco, E.C.; Hagen, F.; Meis, J.F.; Colombo, A.L. First Report of Candida auris in America: Clinical and microbiological aspects of 18 episodes of Candidemia. J. Infect. 2016, 73, 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudramurthy, S.M.; Chakrabarti, A.; Paul, R.A.; Sood, P.; Kaur, H.; Capoor, M.R.; Kindo, A.J.; Marak, R.S.K.; Arora, A.; Sardana, R.; et al. Candida auris Candidaemia in Indian icus: Analysis of Risk Factors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1794–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, A.; Tarai, B.; Singh, A.; Sharma, A. Multidrug-resistant Candida auris infections in critically ill coronavirus disease patients, India, April–July 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2694–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prestel, C.; Anderson, E.; Forsberg, K.; Lyman, M.; de Perio, M.A.; Kuhar, D.; Edwards, K.; Rivera, M.; Shugart, A.; Walters, M.; et al. Candida auris outbreak in a covid-19 Specialty Care Unit—Florida, July–August 2020. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 56–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva-Lozano, H.; de J Treviño-Rangel, R.; González, G.M.; Ramírez-Elizondo, M.T.; Lara-Medrano, R.; Aleman-Bocanegra, M.C.; Guajardo-Lara, C.E.; Gaona-Chávez, N.; Castilleja-Leal, F.; Torre-Amione, G.; et al. Outbreak of Candida auris infection in a COVID-19 hospital in Mexico. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 813–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munshi, A.; Almadani, F.; Ossenkopp, J.; Alharbi, M.; Althaqafi, A.; Alsaedi, A.; Al-Amri, A.; Almarhabi, H. Risk factors, antifungal susceptibility, complications, and outcome of Candida auris bloodstream infection in a tertiary care center in the Western Region of Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2024, 17, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alshamrani, M.M.; El-Saed, A.; Mohammed, A.; Alghoribi, M.F.; Al Johani, S.M.; Cabanalan, H.; Balkhy, H.H. Management of Candida auris outbreak in a tertiary-care setting in Saudi Arabia. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2020, 42, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | Colonization Group (n = 290) | Infection Group (n = 44) | Total (N = 334) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean ± SD | 66.13 ± 16.96 | 68.20 ± 15.61 | 66.4 ± 16.8 | 0.4467 |

| Men, n (%) | 166 (57.2) | 24 (54.5) | 190 (56) | 0.7365 |

| BMI, mean ± SD | 30.3 ± 9.3 | 28.7 ± 8.4 | 30.1 ± 9.2 | 0.30 |

| WBC count, mean ± SD | 11.71 ± 6.75 | 11.46 ± 5.85 | 11.7 ± 6.6 | 0.8177 |

| CRP, median (IQR) | 65 (25–146) | 65 (36–117) | 65 (25–146) | 0.9188 |

| Procalcitonin, median (IQR) | 0.63 (0.17–2.33) | 0.475 (0.275–1.155) | 0.61 (0.19–2.06) | 0.876 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, mean ± SD | 4.79 ± 2.7 | 5.9 ± 3.1 | 4.9 ± 2.8 | 0.0112 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 168 (57.9) | 30 (68.2) | 198 (59.3) | 0.1972 |

| With complications, n (%) | 25 (8.6) | 2 (4.55) | 27 (8.08) | 0.3555 |

| Without complications, n (%) | 143 (49.3) | 28 (63.6) | 171 (51.2) | 0.0765 |

| Moderate to severe CKD, n (%) | 66 (22.76) | 11 (25) | 77 (23.1) | 0.7422 |

| Malignancy | 32 (11.03) | 6 (13.64) | 38 (11.38) | 0.6125 |

| Solid tumor, localized, n (%) | 20 (6.9) | 4 (9.09) | 24 (7.19) | 0.5994 |

| Solid tumor, metastasized, n (%) | 8 (2.76) | 2 (4.55) | 10 (2.99) | 0.5170 |

| Hematologic, n (%) | 4 (1.38) | 0 (0) | 4 (1.2) | 0.4332 |

| Immunosuppression, n (%) | 39 (13.45) | 7 (15.91) | 46 (13.77) | 0.6589 |

| Multi-site colonization, n (%) | 137 (47.24) | 24 (54.5) | 161 (48.2) | 0.3663 |

| Source of colonization, n (%) | ||||

| Axilla | 100 (34.48) | 12 (27.27) | 112 (33.53) | 0.3452 |

| Groin | 114 (39.31) | 14 (31.82) | 128 (38.32) | 0.3408 |

| Rectal | 43 (14.83) | 11 (25.00) | 54 (16.17) | 0.0877 |

| Nasal | 25 (8.62) | 6 (13.64) | 31 (9.28) | 0.2853 |

| Urine | 8 (2.76) | 1 (2.27) | 9 (2.69) | 0.8529 |

| ICU admission before colonization, n (%) | 264 (91.0) | 40 (90.9) | 304 (91.0) | 0.9784 |

| Central line, n (%) | 208 (71.7) | 40 (90.9) | 248 (74.25) | 0.0067 |

| Foley catheter, n (%) | 204 (70.34) | 37 (84.1) | 241 (72.2) | 0.0580 |

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 175 (60.34) | 34 (77.3) | 209 (62.6) | 0.0306 |

| Antibiotic exposure (past 90 days), n (%) | 260 (89.66) | 42 (95.45) | 302 (90.4) | 0.2233 |

| Duration of prior antibiotic use, days, median (IQR) | 7 (3–10) | 7 (4–11) | 7 (3–10) | 0.4121 |

| Antibiotic used for ≥48 h, n (%) | ||||

| Ceftriaxone | 15 (5.17) | 0 (0) | 15 (4.49) | 0.1227 |

| Linezolid | 7 (2.41) | 0 (0) | 7 (2.1) | 0.2976 |

| Meropenem (Single agent) | 82 (28.28) | 7 (15.91) | 89 (26.65) | 0.0838 |

| Meropenem (Combination) | 7 (2.41) | 1 (2.27) | 8 (2.4) | 0.9545 |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | 92 (31.7) | 16 (36.36) | 108 (32.34) | 0.5398 |

| Vancomycin | 25 (8.62) | 6 (13.6) | 31 (9.28) | 0.2853 |

| Other * | 32 (11.03) | 14 (31.8) | 46 (13.77) | 0.0002 |

| TPN within 30 days prior to colonization, n (%) | 5 (1.72) | 3 (6.82) | 8 (2.4) | 0.0395 |

| Previous abdominal surgery within 30 days of colonization, n (%) | 14 (4.83) | 6 (13.64) | 20 (5.99) | 0.0217 |

| Previous hospitalization within three months of colonization, n (%) | 115 (39.66) | 20 (45.45) | 135 (40.4) | 0.4651 |

| Previous hospitalization within six months of colonization, n (%) | 122 (42.1) | 17 (38.64) | 139 (41.6) | 0.6669 |

| HIV, n (%) | 1 (0.34) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | 0.6965 |

| Variable | Cohort |

|---|---|

| Days from colonization to a positive culture, median (IQR) | 21 (12–35) |

| Source of positive C. auris culture, n (%) | |

| Urine | 25 (56.82) |

| Blood | 19 (43.18) |

| Echinocandins Resistance, n (%) * | |

| Anidulafungin | 1/20 (5) |

| Caspofungin | 3/20 (15) |

| Outcomes | Colonization Group (n = 290) | Infection Group (n = 44) | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital mortality, n (%) | 96 (33.1) | 29 (65.9) | 3.91 (2.0–7.6) | 0.0001 |

| Mortality within 30 days of colonization, n (%) | 69 (23.79) | 11 (25) | 1.07 (0.51–2.22) | 0.8613 |

| Time to death, days, median (IQR) | 15 (5–40) | 43 (25–88) | N/A | 0.000233 |

| Length of ICU stay, days, median (IQR) | 17 (7–36) | 30 (10–66) | N/A | 0.03196 |

| Length of hospital stay, days, median (IQR) | 40 (20–83) | 73 (43–147) | N/A | 0.000446 |

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Central venous catheter | 1.77 | 0.54–5.71 | 0.34 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 1.42 | 0.60–3.3 | 0.42 |

| TPN within 30 days | 1.45 | 0.22–9.14 | 0.7 |

| Abdominal surgery within 30 days | 4.08 | 1.1–15.12 | 0.03 |

| In-hospital mortality | 7.8 | 3.28–18.5 | <0.001 |

| 30-day mortality | 0.27 | 0.11–0.66 | 0.005 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alowais, S.A.; Wali, H.A.; bin Saleh, K.; Aldugiem, R.; Alsaeed, Y.; Almutairi, M.; Almangour, T.A.; Alsowaida, Y.S.; Bosaeed, M. Risk Factors and Outcomes for Invasive Infection Among Patients Colonized with Candidozyma auris: A Case–Control Study. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121206

Alowais SA, Wali HA, bin Saleh K, Aldugiem R, Alsaeed Y, Almutairi M, Almangour TA, Alsowaida YS, Bosaeed M. Risk Factors and Outcomes for Invasive Infection Among Patients Colonized with Candidozyma auris: A Case–Control Study. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(12):1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121206

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlowais, Shuroug A., Haytham A. Wali, Khalid bin Saleh, Rema Aldugiem, Yara Alsaeed, Meshari Almutairi, Thamer A. Almangour, Yazed S. Alsowaida, and Mohammad Bosaeed. 2025. "Risk Factors and Outcomes for Invasive Infection Among Patients Colonized with Candidozyma auris: A Case–Control Study" Antibiotics 14, no. 12: 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121206

APA StyleAlowais, S. A., Wali, H. A., bin Saleh, K., Aldugiem, R., Alsaeed, Y., Almutairi, M., Almangour, T. A., Alsowaida, Y. S., & Bosaeed, M. (2025). Risk Factors and Outcomes for Invasive Infection Among Patients Colonized with Candidozyma auris: A Case–Control Study. Antibiotics, 14(12), 1206. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14121206