Green Synthesized Copper-Oxide Nanoparticles Exhibit Antifungal Activity Against Botrytis cinerea, the Causal Agent of the Gray Mold Disease

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

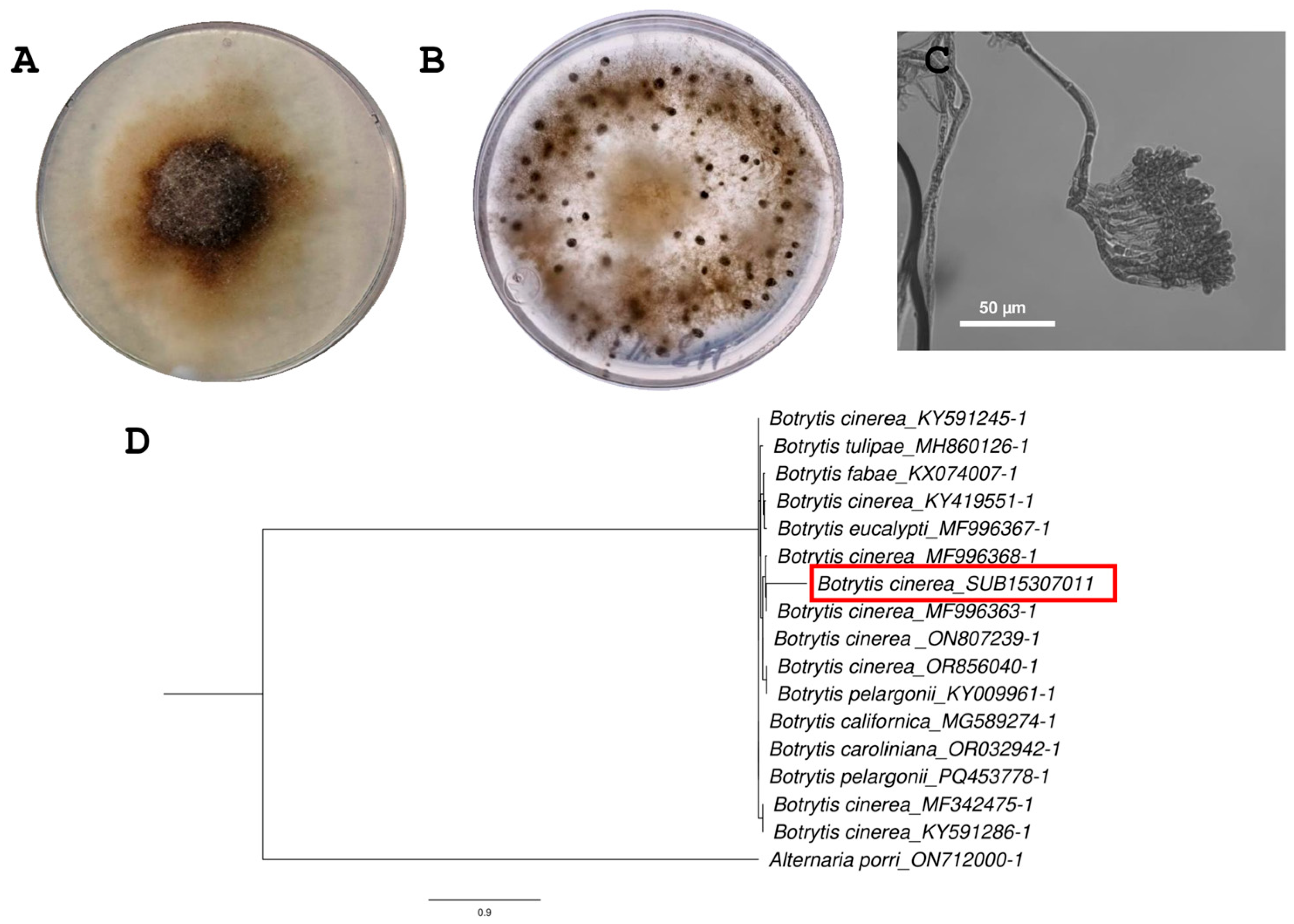

2.1. Identification of B. cinerea H13

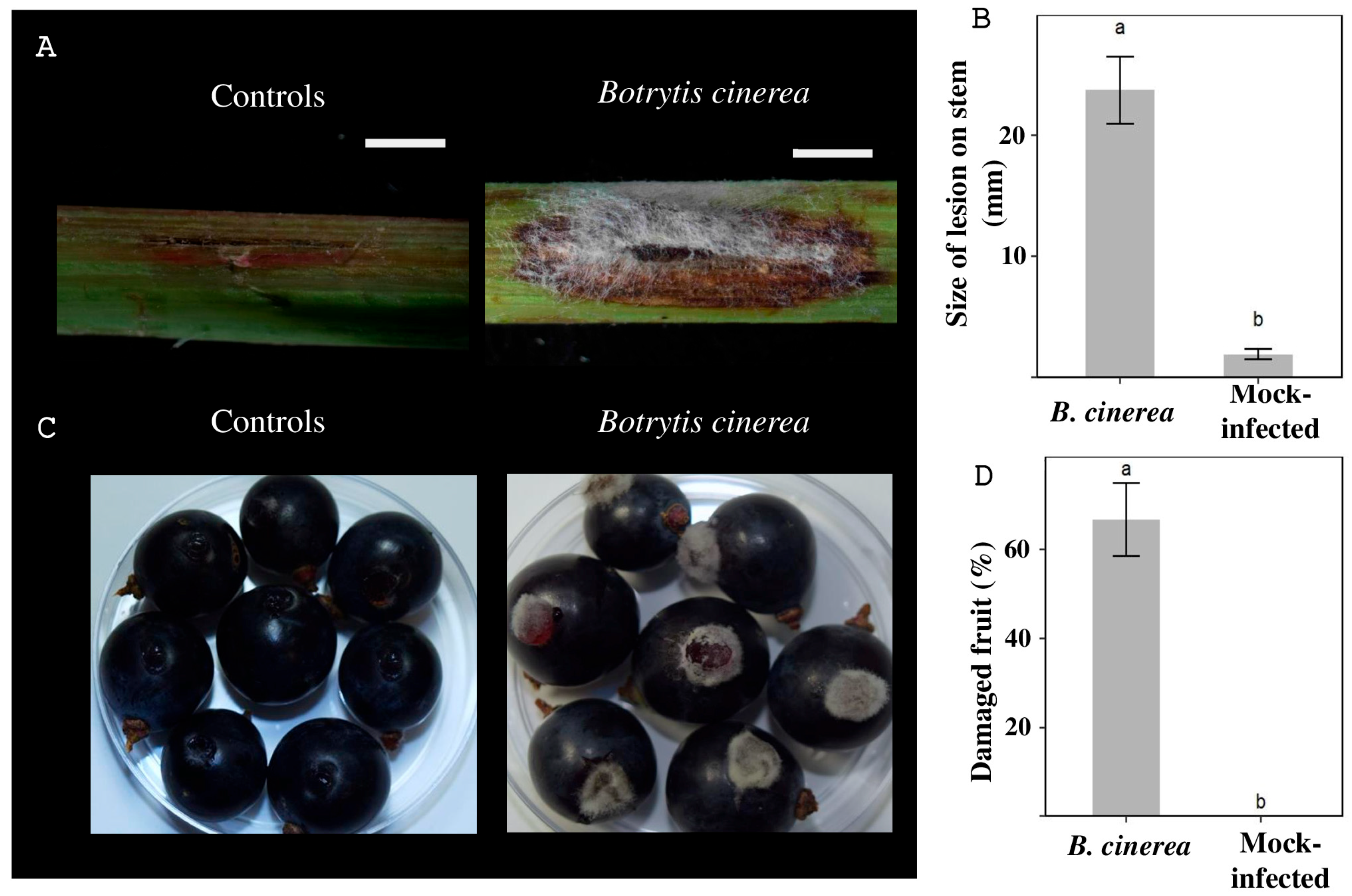

2.2. Plant Virulence Assay

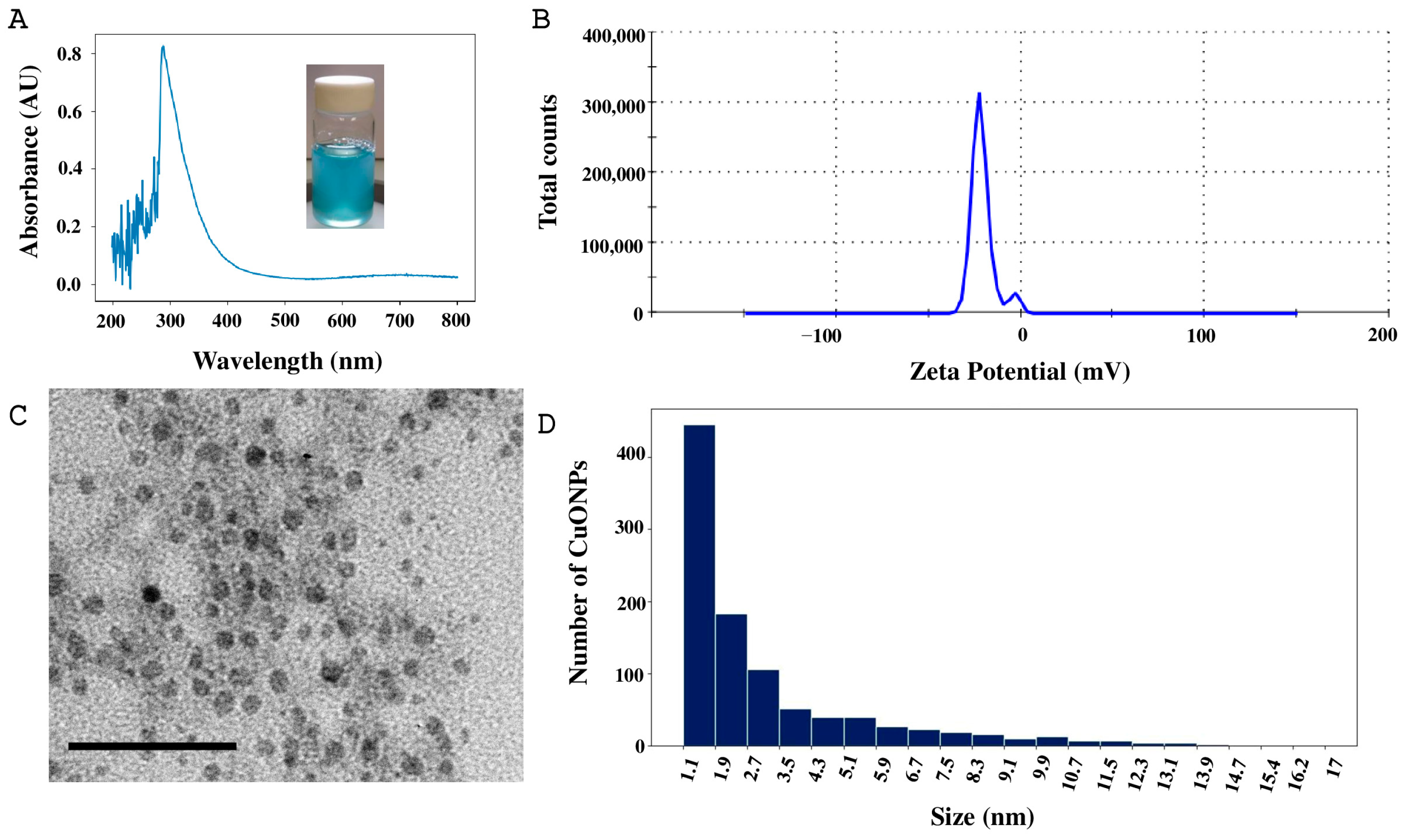

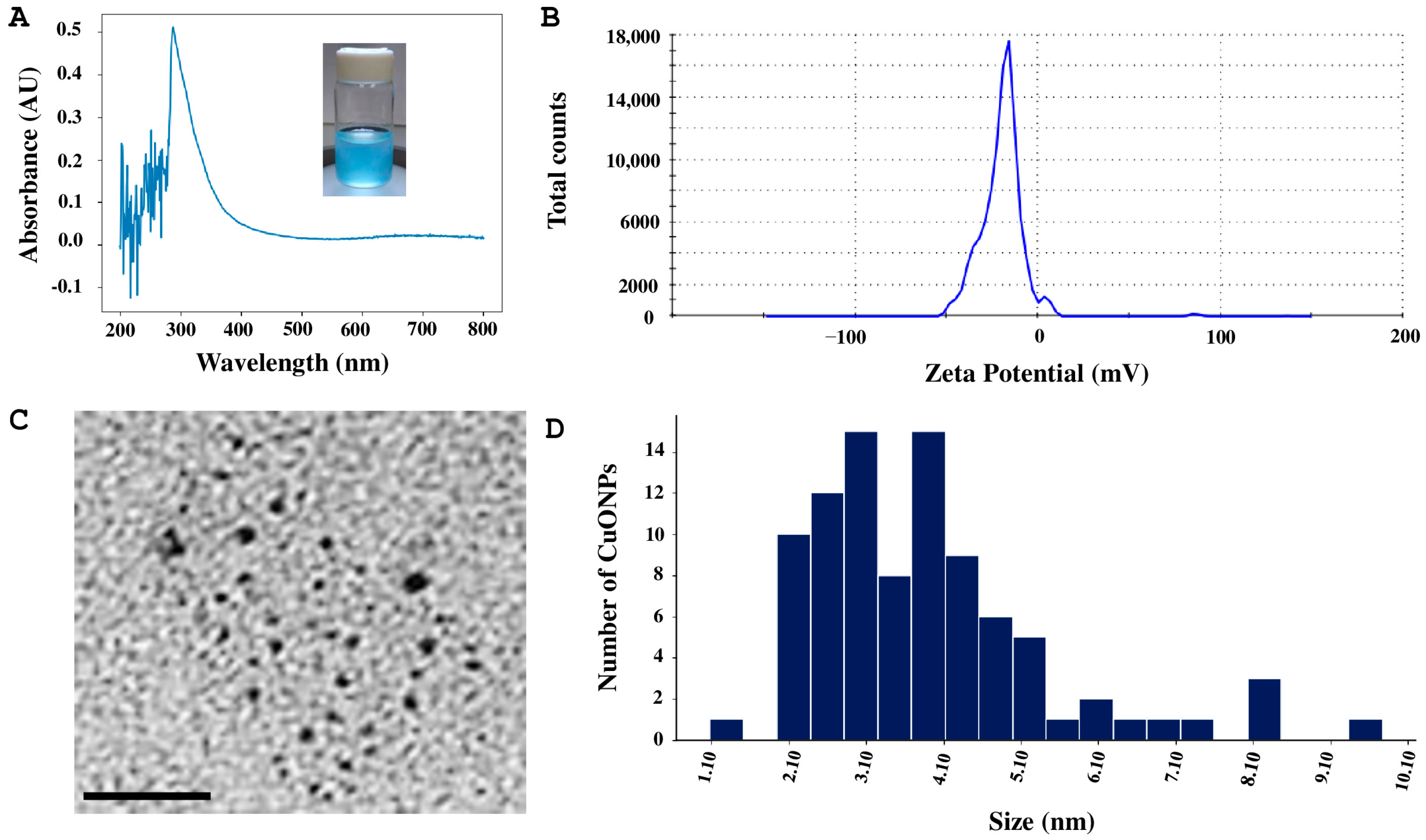

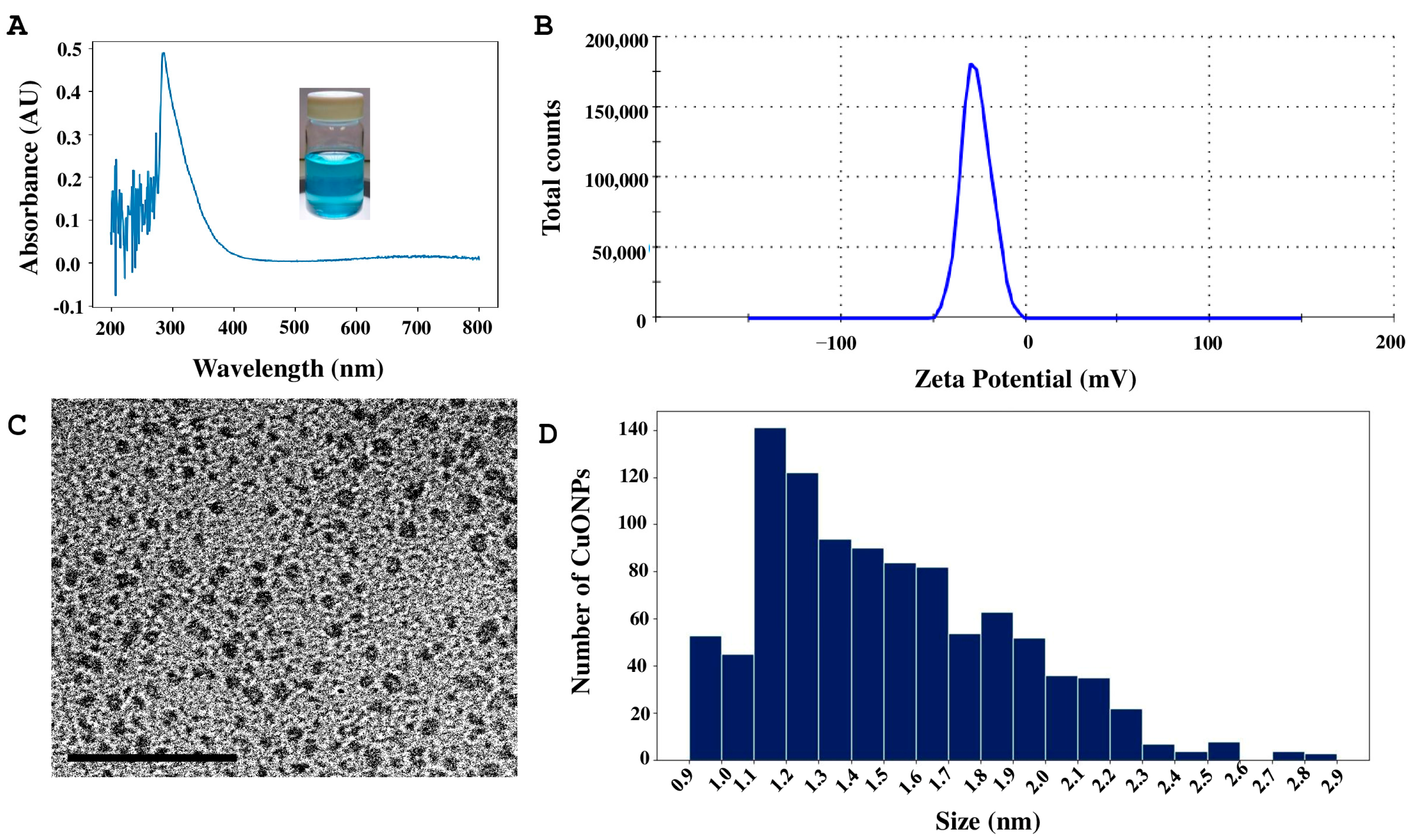

2.3. Copper Oxide Nanoparticles Characterization

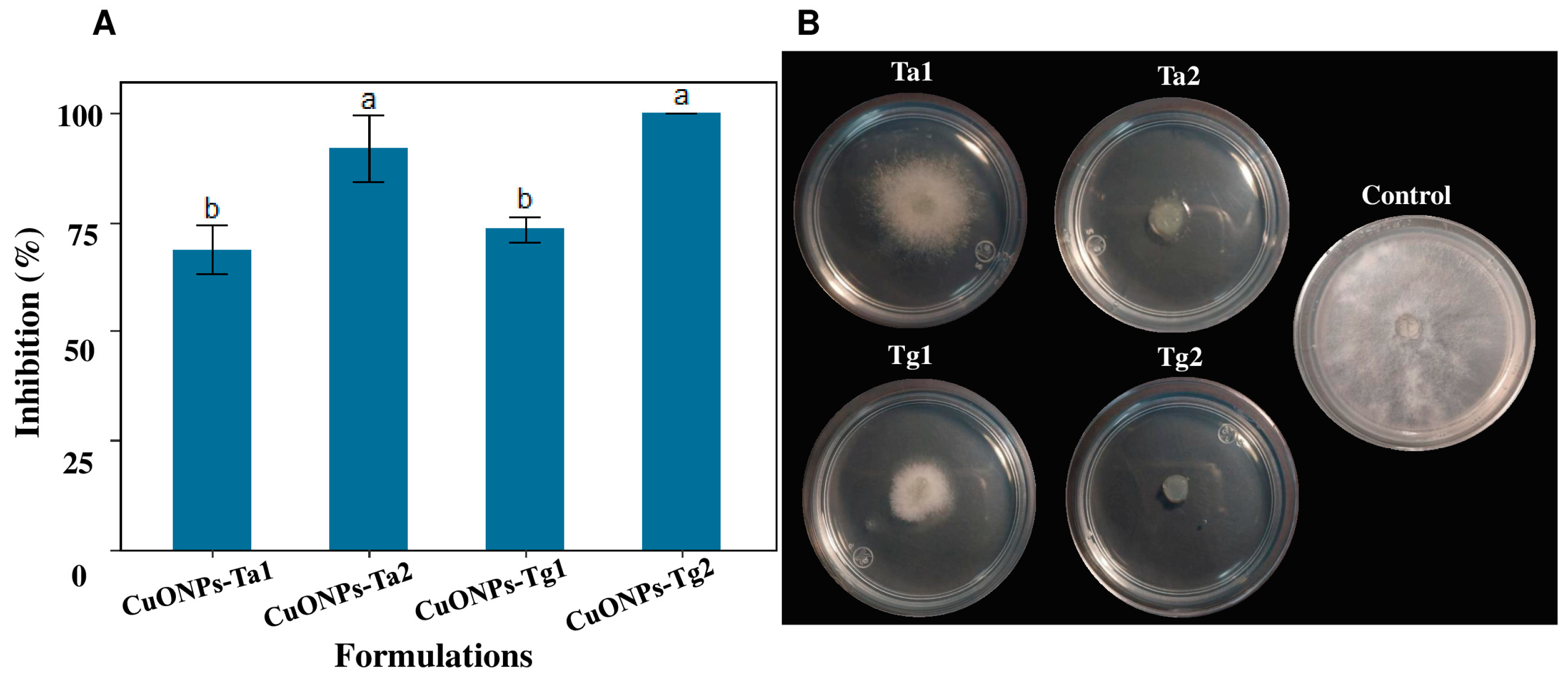

2.4. Antifungal Properties of CuONPs Against B. cinerea CDBBH1556

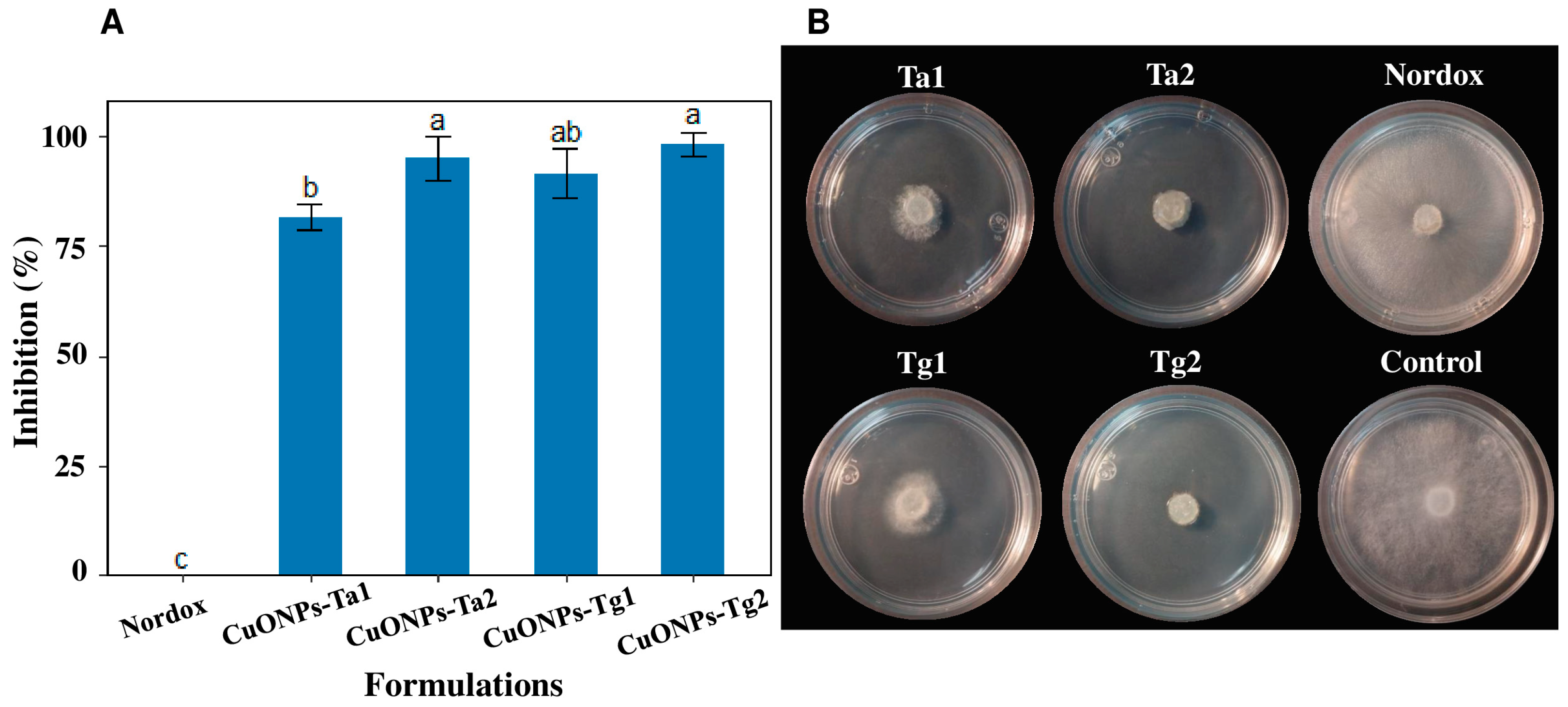

2.5. Antifungal Properties of CuONPs Against B. cinerea Isolated from the Field

2.6. Antifungal Properties of Trichoderma Supernatants Against B. cinerea Isolated from the Field

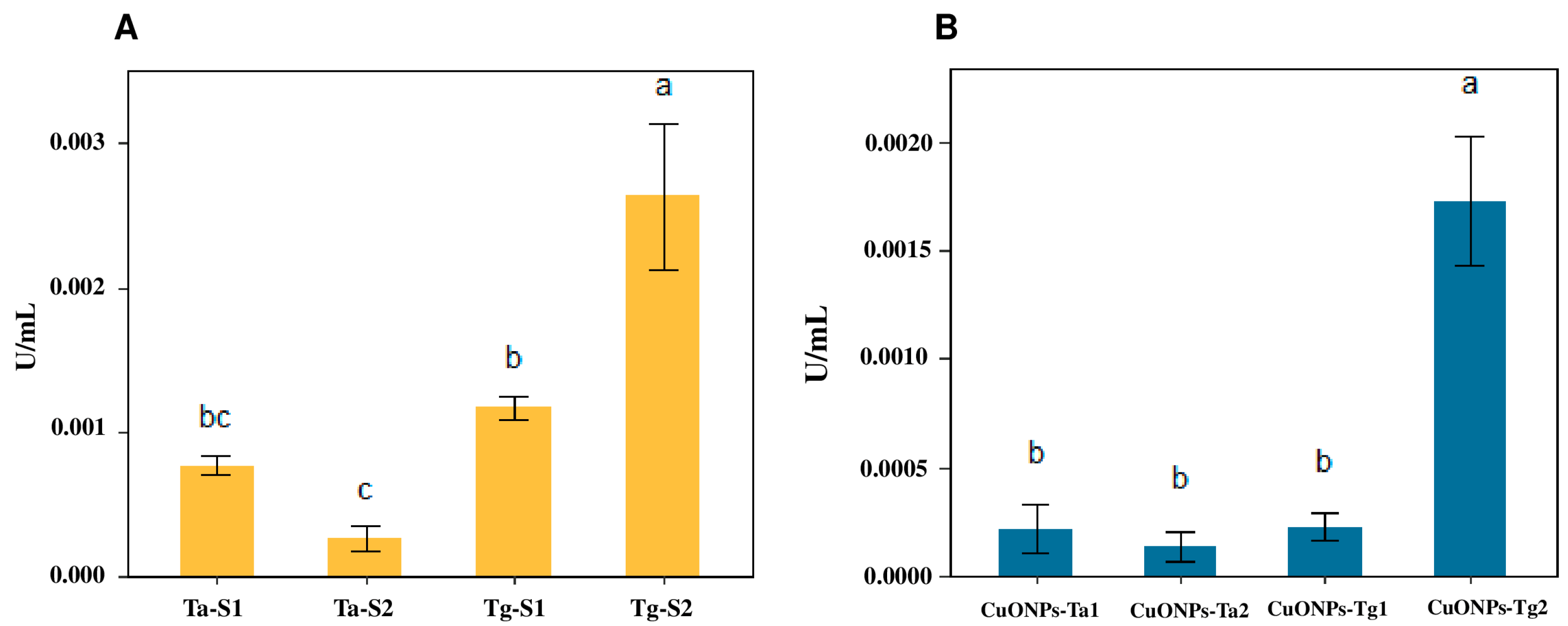

2.7. Chitinase Assays

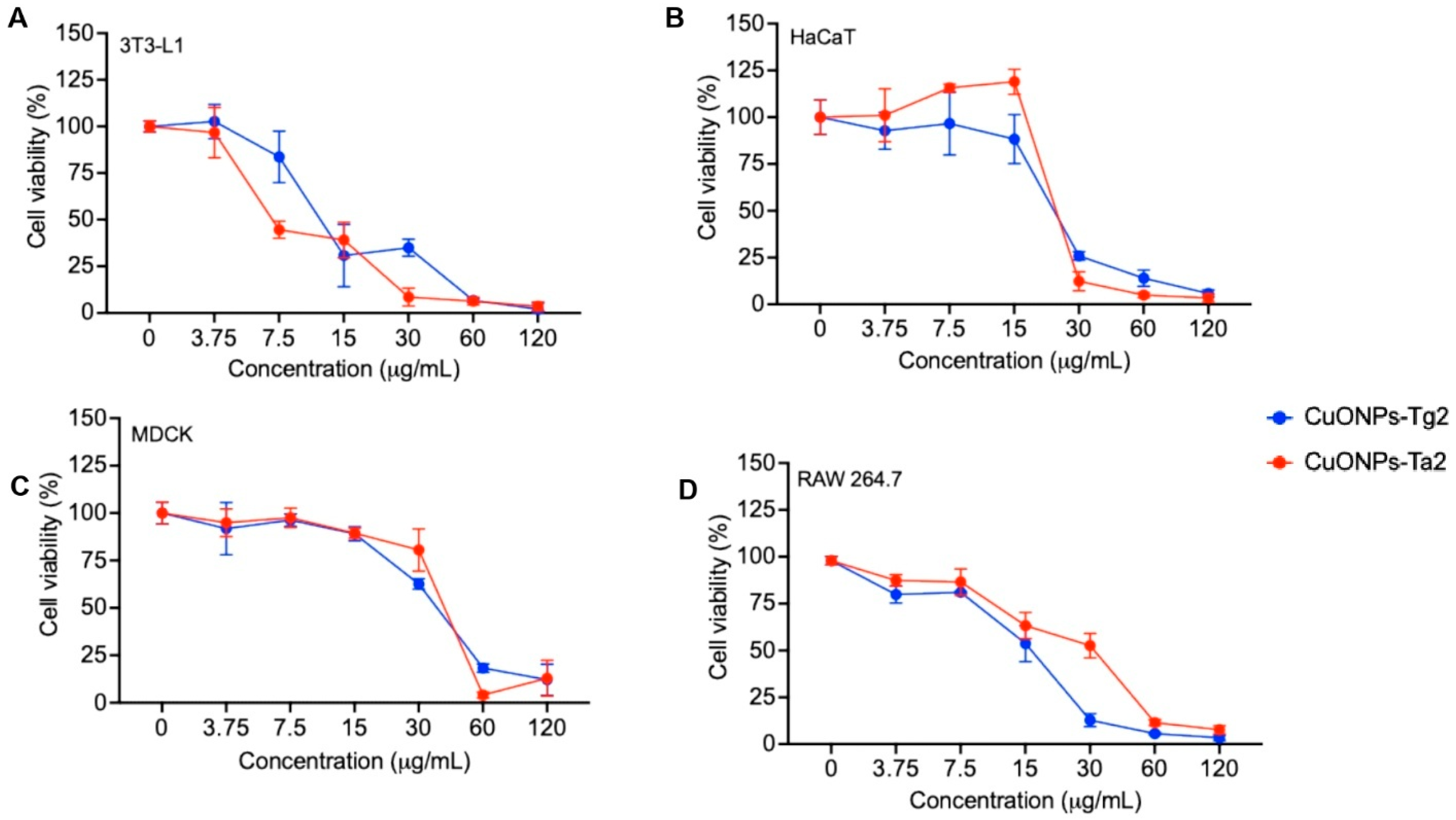

2.8. Biocompatibility Evaluation

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Strains, Media and Growth Conditions

4.2. Morphological and Molecular Identification of B. cinerea H13

4.3. Plant Virulence Assay for B. cinerea H13

4.4. Supernatants Obtention

4.5. Biosynthesis and Characterization of CuONPs

4.6. Assessment of Antifungal Properties of CuONPs Against B. cinerea CDBBH1556

4.7. Assessment of CuONPs Antifungal Properties Against B. cinerea Isolated from the Field

4.8. Assessment of Antifungal Properties of Trichoderma Supernatants Against B. cinerea Isolated from the Field

4.9. Chitinase Activity Assays

4.10. Biocompatibility Evaluation Assays

4.10.1. Cell Culture

4.10.2. Cell Viability Assay

4.10.3. Reactive Oxygen Production

4.10.4. Production of Nitrite by Macrophages

4.11. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CuONPs | Copper oxide nanoparticles |

| MM | Minimal Medium |

| PDA | Potato Dextrose Agar |

| ITS | Internal Transcribed Spacers |

| MIC | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

References

- Cheung, N.; Tian, L.; Liu, X.; Li, X. The Destructive Fungal Pathogen Botrytis cinerea—Insights from Genes Studied with Mutant Analysis. Pathogens 2020, 9, 923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, L.; Yong, C.; Zhanquan, Z.; Boqiang, L.; Guozheng, Q.; Shiping, T. Pathogenic mechanisms and control strategies of Botrytis cinerea causing post-harvest decay in fruits and vegetables. Food Qual. Saf. 2018, 2, 111–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rupp, S.; Weber, R.W.S.; Rieger, D.; Detzel, P.; Hahn, M. Spread of Botrytis cinerea strains with multiple fungicide resistance in german horticulture. Front. Microbiol. 2017, 7, 228887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garinie, T.; Nusillard, W.; Lelièvre, Y.; Taranu, Z.E.; Goubault, M.; Thiéry, D.; Moreau, J.; Louâpre, P. Adverse effects of the Bordeaux mixture copper-based fungicide on the non-target vineyard pest Lobesia botrana. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 4790–4799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrios, G.N. Control of plant diseases. In Plant Pathology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005; pp. 293–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Dong, S.; Su, X. Copper and other heavy metals in grapes: A pilot study tracing influential factors and evaluating potential risks in China. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 17407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renan, L. Effect of long-term applications of copper on soil and grape copper (Vitis vinifera). Can. J. Soil Sci. 1994, 74, 345–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hahn, M. The rising threat of fungicide resistance in plant pathogenic fungi: Botrytis as a case study. J. Chem. Biol. 2014, 7, 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajput, P.; Thakur, A.; Devi, P. Emerging agrochemicals contaminants: Current status, challenges, and technological solutions. In Agrochemicals Detection, Treatment and Remediation: Pesticides and Chemical Fertilizers; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 117–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kausar, H.; Mehmood, A.; Khan, R.T.; Ahmad, K.S.; Hussain, S.; Nawaz, F.; Iqbal, M.S.; Nasir, M.; Ullah, T.S. Green synthesis and characterization of copper nanoparticles for investigating their effect on germination and growth of wheat. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malandrakis, A.A.; Krasagakis, N.; Kavroulakis, N.; Ilias, A.; Tsagkarakou, A.; Vontas, J.; Markakis, E. Fungicide resistance frequencies of Botrytis cinerea greenhouse isolates and molecular detection of a novel SDHI resistance mutation. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2022, 183, 105058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, R.; Roy, T.; Adak, P. A Review of The Impact of Nanoparticles on Environmental Processes. BIO Web Conf. 2024, 86, 01001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santás-Miguel, V.; Arias-Estévez, M.; Rodríguez-Seijo, A.; Arenas-Lago, D. Use of metal nanoparticles in agriculture. A review on the effects on plant germination. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 334, 122222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Valdespino, C.A.; Orrantia-Borunda, E. Trichoderma and Nanotechnology in Sustainable Agriculture: A Review. Front. Fungal Biol. 2021, 2, 764675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaddam, A.B.; Namvar, F.; Moniri, M.; Tahir, P.M.; Azizi, S.; Mohamad, R. Nanoparticles Biosynthesized by Fungi and Yeast: A Review of Their Preparation, Properties, and Medical Applications. Molecules 2015, 20, 16540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, N.; Srividhya, S. Secondary metabolites and lytic tool box of Trichoderma and their role in plant health. In Molecular Aspects of Plant Beneficial Microbes in Agriculture; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2020; pp. 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, Y.; Martínez-Soto, D.; de los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Garcia-Marin, L.E.; Juarez-Moreno, K.; Castro-Longoria, E. Potential application of a fungal co-culture crude extract for the conservation of post-harvest fruits. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2024, 55, 1679–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar, K.; Shanmugam, S.; Varukattu, N.B.; MubarakAli, D.; Kathiresan, K.; Wang, M.H. Biosynthesis and characterization of copper oxide nanoparticles from indigenous fungi and its effect of photothermolysis on human lung carcinoma. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 2019, 190, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consolo, V.F.; Torres-Nicolini, A.; Alvarez, V.A. Mycosinthetized Ag, CuO and ZnO nanoparticles from a promising Trichoderma harzianum strain and their antifungal potential against important phytopathogens. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 20499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Soto, D.; Campos-Jiménez, E.; Cabello-Pasini, A.; Garcia-Marin, L.E.; Meza-Villezcas, A.; Castro-Longoria, E. Evaluation of Fungal Sensitivity to Biosynthesized Copper-Oxide Nanoparticles (CuONPs) in Grapevine Tissues and Fruits. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadek, M.E.; Shabana, Y.M.; Sayed-Ahmed, K.; Tabl, A. Antifungal Activities of Sulfur and Copper Nanoparticles against Cucumber Postharvest Diseases Caused by Botrytis cinerea and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feigl, G. The impact of copper oxide nanoparticles on plant growth: A comprehensive review. J. Plant Interact. 2023, 18, 2243098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Longoria, E. Biosynthesis of Metal-Based Nanoparticles by Trichoderma and Its Potential Applications 2022. In Advances in Trichoderma Biology for Agricultural Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2022; pp. 433–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Abeid, S.E.; Mosa, M.A.; El-Tabakh, M.A.M.; Saleh, A.M.; El-Khateeb, M.A.; Haridy, M.S.A. Antifungal activity of copper oxide nanoparticles derived from Zizyphus spina leaf extract against Fusarium root rot disease in tomato plants. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2024, 22, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaba, S.; Rai, A.K.; Varma, A.; Prasad, R.; Goel, A. Biocontrol potential of mycogenic copper oxide nanoparticles against Alternaria brassicae. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 966396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Marin, L.E.; Juarez-Moreno, K.; Vilchis-Nestor, A.R.; Castro-Longoria, E. Highly Antifungal Activity of Biosynthesized Copper Oxide Nanoparticles against Candida albicans. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán-Guzmán, P.; Kumar, A.; de los Santos-Villalobos, S.; Parra-Cota, F.I.; Orozco-Mosqueda, M.d.C.; Fadiji, A.E.; Hyder, S.; Babalola, O.O.; Santoyo, G. Trichoderma Species: Our Best Fungal Allies in the Biocontrol of Plant Diseases—A Review. Plants 2023, 12, 432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stracquadanio, C.; Quiles, J.M.; Meca, G.; Cacciola, S.O. Antifungal Activity of Bioactive Metabolites Produced by Trichoderma asperellum and Trichoderma atroviride in Liquid Medium. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Yu, S.; Yu, D.; Liu, N.; Tang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, A. Biogenic Trichoderma harzianum-derived selenium nanoparticles with control functionalities originating from diverse recognition metabolites against phytopathogens and mycotoxins. Food Control 2019, 106, 106748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilger-Casagrande, M.; Germano-Costa, T.; Pasquoto-Stigliani, T.; Fraceto, L.F.; de Lima, R. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles employing Trichoderma harzianum with enzymatic stimulation for the control of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, A.; Saeed, H.; Iqtedar, M.; Hussain, S.Z.; Kaleem, A.; Abdullah, R.; Sharif, S.; Naz, S.; Saleem, F.; Aihetasham, A.; et al. Size-Controlled Production of Silver Nanoparticles by Aspergillus fumigatus BTCB10: Likely Antibacterial and Cytotoxic Effects. J. Nanomater. 2019, 2019, 5168698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, K.M.; Ajitha, B.; Ashok Kumar Reddy, Y.; Suneetha, Y.; Sreedhara Reddy, P. Synthesis of copper nanoparticles and role of pH on particle size control. Mater. Today Proc. 2016, 3, 1985–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuevas, R.; Durán, N.; Diez, M.C.; Tortella, G.R.; Rubilar, O. Extracellular Biosynthesis of Copper and Copper Oxide Nanoparticles by Stereum hirsutum, a Native White-Rot Fungus from Chilean Forests. J. Nanomater. 2015, 1, 789089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sintubin, L.; De Windt, W.; Dick, J.; Mast, J.; Van Der Ha, D.; Verstraete, W.; Boon, N. Lactic acid bacteria as reducing and capping agent for the fast and efficient production of silver nanoparticles. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 741–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, R.; Khan, M.A.; Ahmad, M.; Ahmad, M.M.; Abdin, M.Z.; Musarrat, J.; Javed, S. Chitinases: An update. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2013, 5, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loc, N.H.; Huy, N.D.; Quang, H.T.; Lan, T.T.; Thu Ha, T.T. Characterisation and antifungal activity of extracellular chitinase from a biocontrol fungus, Trichoderma asperellum PQ34. Mycology 2019, 11, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonglom, P.; Daengsuwan, W.; Ito, S.i.; Sunpapao, A. Biological control of Sclerotium fruit rot of snake fruit and stem rot of lettuce by Trichoderma sp. T76-12/2 and the mechanisms involved. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2019, 107, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubicek, C.P.; Herrera-Estrella, A.; Seidl-Seiboth, V.; Martinez, D.A.; Druzhinina, I.S.; Thon, M.; Zeilinger, S.; Casas-Flores, S.; Horwitz, B.A.; Mukherjee, P.K.; et al. Comparative genome sequence analysis underscores mycoparasitism as the ancestral life style of Trichoderma. Genome Biol. 2011, 12, R40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Horwitz, B.A.; Kenerley, C.M. Secondary metabolism in Trichoderma—A genomic perspective. Microbiology 2012, 158, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadi-Nouraldinvand, F.; Afrouz, M.; Elias, S.G.; Eslamian, S. Green synthesis of copper nanoparticles extracted from guar seedling under Cu heavy-metal stress by Trichoderma harzianum and their bio-efficacy evaluation against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Environ. Earth Sci. 2022, 81, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, Y.N.; Bach, H. Mechanisms of Antifungal Properties of Metal Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, M.; Pandurangan, P.; Ramasami, N.; Rajendran, S.B.; Sangilimuthu, S.N.; Perumal, P. Highly potential antifungal activity of quantum-sized silver nanoparticles against Candida albicans. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2014, 173, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parada, J.; Tortella, G.; Seabra, A.B.; Fincheira, P.; Rubilar, O. Potential Antifungal Effect of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles Combined with Fungicides against Botrytis cinerea and Fusarium oxysporum. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naz, S.; Gul, A.; Zia, M. Toxicity of copper oxide nanoparticles: A review study. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2020, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavil-Guerrero, E.; Vazquez-Duhalt, R.; Juarez-Moreno, K. Exploring the cytotoxicity mechanisms of copper ions and copper oxide nanoparticles in cells from the excretory system. Chemosphere 2024, 347, 140713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, G.; Cappellini, F.; Farcal, L.; Gornati, R.; Bernardini, G.; Fadeel, B. Copper oxide nanoparticles trigger macrophage cell death with misfolding of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1). Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2022, 19, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valodkar, M.; Rathore, P.S.; Jadeja, R.N.; Thounaojam, M.; Devkar, R.V.; Thakore, S. Cytotoxicity evaluation and antimicrobial studies of starch capped water soluble copper nanoparticles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 201, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellemain, E.; Carlsen, T.; Brochmann, C.; Coissac, E.; Taberlet, P.; Kauserud, H. ITS as an environmental DNA barcode for fungi: An in silico approach reveals potential PCR biases. BMC Microbiol. 2010, 10, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmölz, L.; Wallert, M.; Lorkowski, S. Optimized incubation regime for nitric oxide measurements in murine macrophages using the Griess assay. J. Immunol. Methods 2017, 449, 68–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Treatment (CuONPs) | 130 μg/mL | 140 μg/mL | 150 μg/mL | 160 μg/mL | 170 μg/mL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CuONPs-Ta1 | 11.66 ± 7.6 | 16.6 ± 5.7 | 40 ± 8.6 | 68.6 ± 5.5 | 96.66 ± 5.7 |

| CuONPs-Ta2 | 63.3 ± 5.7 | 60 ± 10 | 81.6 ± 10.4 | 91.6 ± 7.6 | 98.33 ± 2.8 |

| CuONPs-Tg1 | 41.66 ± 14.4 | 58.33 ± 7.6 | 46.6 ± 7.6 | 73.33 ± 2.8 | 98.33 ± 2.8 |

| CuONPs-Tg2 | 76.6 ± 5.7 | 75 ± 5 | 90 ± 8.6 | 100 ± 0 | 100 ± 0 |

| Treatment (CuONPs) | IC50 μg/mL | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3T3-L1 | HaCaT | MDCK | RAW 264.7 | |

| CuONPs-Tg2 | 14.05 ± 0.881 R2: 0.880 | 10.74 ± 0.936 R2: 0.936 | 7.849 ± 0.955 R2: 0.955 | 8.103 ± 0.948 R2: 0.948 |

| CuONPs-Ta2 | 11.63 ± 0.891 R2: 0.891 | 12.46 ± 0.951 R2: 0.951 | 9.73 ± 0.946 R2: 0.946 | 8.221 ± 0.942 R2: 0.943 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Campos-Jiménez, E.; Juarez-Moreno, K.; Martínez-Soto, D.; Cabello-Pasini, A.; Castro-Longoria, E. Green Synthesized Copper-Oxide Nanoparticles Exhibit Antifungal Activity Against Botrytis cinerea, the Causal Agent of the Gray Mold Disease. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111099

Campos-Jiménez E, Juarez-Moreno K, Martínez-Soto D, Cabello-Pasini A, Castro-Longoria E. Green Synthesized Copper-Oxide Nanoparticles Exhibit Antifungal Activity Against Botrytis cinerea, the Causal Agent of the Gray Mold Disease. Antibiotics. 2025; 14(11):1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111099

Chicago/Turabian StyleCampos-Jiménez, Erisneida, Karla Juarez-Moreno, Domingo Martínez-Soto, Alejandro Cabello-Pasini, and Ernestina Castro-Longoria. 2025. "Green Synthesized Copper-Oxide Nanoparticles Exhibit Antifungal Activity Against Botrytis cinerea, the Causal Agent of the Gray Mold Disease" Antibiotics 14, no. 11: 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111099

APA StyleCampos-Jiménez, E., Juarez-Moreno, K., Martínez-Soto, D., Cabello-Pasini, A., & Castro-Longoria, E. (2025). Green Synthesized Copper-Oxide Nanoparticles Exhibit Antifungal Activity Against Botrytis cinerea, the Causal Agent of the Gray Mold Disease. Antibiotics, 14(11), 1099. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics14111099