A Study Review of the Appropriateness of Oral Antibiotic Discharge Prescriptions in the Emergency Department at a Rural Hospital in Mississippi, USA

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

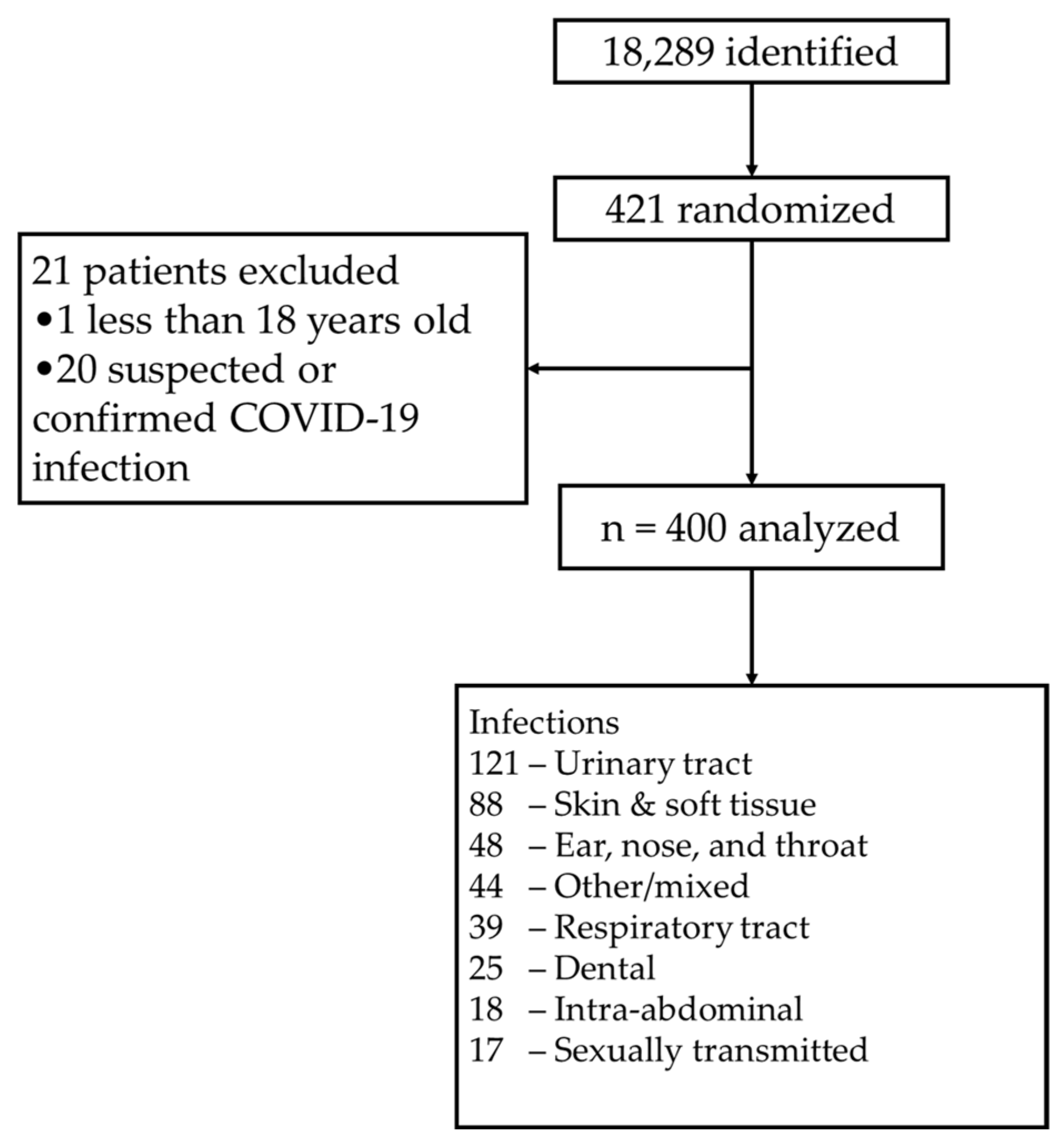

4.1. Trial Design and Oversight

4.2. Study Outcome

4.3. Study Population

4.4. Data Collection and Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- May, L.S.; Quirós, A.M.; Oever, J.T.; Hoogerwerf, J.J.; Schoffelen, T.; Schouten, J.A. Antimicrobial Stewardship in the Emergency Department: Characteristics and Evidence for Effectiveness of Interventions. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 204–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooda, K.; Canterbury, E.; Bellolio, F. Impact of Pharmacist-Led Antimicrobial Stewardship on Appropriate Antibiotic Prescribing in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann. Emerg. Med. 2022, 79, 374–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortmann, M.J.; Johnson, E.G.; Jarrell, D.H.; Bilhimer, M.; Hayes, B.D.; Mishler, A.; Pugliese, R.S.; Roberson, T.A.; Slocum, G.; Smith, A.P.; et al. ASHP Guidelines on Emergency Medicine Pharmacist Services. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2021, 78, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randolph, T.C.; Parker, A.; Meyer, L.; Zeina, R. Effect of a Pharmacist-Managed Culture Review Process on Antimicrobial Therapy in an Emergency Department. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2011, 68, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, S.N.; Acquisto, N.M.; Ashley, E.D.; Fairbanks, R.J.; Beamish, S.E.; Haas, C.E. Pharmacist-Managed Antimicrobial Stewardship Program for Patients Discharged from the Emergency Department. J. Pharm. Pract. 2012, 25, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.; McGraw, M.A.; Tomsey, A.; Hegde, G.G.; Shang, J.; O’neill, J.M.; Venkat, A. Pharmacist Addition to the Post-ED Visit Review of Discharge Antimicrobial Regimens. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2014, 32, 1270–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bao, H.; Dubrovskaya, Y.; Jen, S.-P.; Decano, A.; Ahmed, N.; Pham, V.P.; Papadopoulos, J.; Siegfried, J. Novel Multidisciplinary Approach for Outpatient Antimicrobial Stewardship Using an Emergency Department Follow-Up Program. J. Pharm. Pract. 2023, 36, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornell, W.K.; Hile, G.; Stone, T.; Hannum, J.; Reichert, M.; Hollinger, M.K. Impact of advanced practice pharmacists on a culture response program in the emergency department. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2022, 79, S106–S114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.; Dewey, M.; Friesner, D. Pharmacist-led urine culture follow-ups in a rural emergency department. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2022, 62, S1544-3191(22)00289-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giruzzi, M.E.; Tawwater, J.C.; Grelle, J.L. Evaluation of Antibiotic Utilization in an Emergency Department After Implementation of an Antimicrobial Stewardship Pharmacist Culture Review Service. Hosp. Pharm. 2020, 55, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingenfelter, E.; Drapkin, Z.; Fritz, K.; Youngquist, S.; Madsen, T.; Fix, M. ED pharmacist monitoring of provider antibiotic selection aids appropriate treatment for outpatient UTI. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2016, 34, 1600–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, L.C.; Covey, R.B.; Weston, J.; Hu, B.B.Y.; Laine, G.A. Pharmacist-driven antimicrobial optimization in the emergency department. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2016, 73, S49–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dumkow, L.E.; Kenney, R.M.; Macdonald, N.C.; Carreno, J.J.; Malhotra, M.K.; Davis, S.L. Impact of a Multidisciplinary Culture Follow-up Program of Antimicrobial Therapy in the Emergency Department. Infect. Dis. Ther. 2014, 3, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rainess, R.A.; Patel, V.V.; Cavanaugh, J.B.; Hill, J. Evaluating the Addition of a Clinical Pharmacist Service to a Midlevel Provider-Driven Culture Follow-up Program in a Community Emergency Department. J. Pharm. Technol. 2021, 37, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.Y.; Balmat, R.; Kahle, M.L.; Blynn, M.; Hipp, R.; Podolsky, S.; Fertel, B.S. Evaluation of a health system-wide pharmacist-driven emergency department laboratory follow-up and antimicrobial management program. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2020, 38, 2591–2595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, L.E.; Gupta, K.; Bradley, S.F.; Colgan, R.; DeMuri, G.P.; Drekonja, D.; Eckert, L.O.; Geerlings, S.E.; Köves, B.; Hooton, T.M.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: 2019 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2019, 68, e83–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Hooton, T.M.; Naber, K.G.; Wullt, B.; Colgan, R.; Miller, L.G.; Moran, G.J.; Nicolle, L.E.; Raz, R.; Schaeffer, A.J.; et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: A 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 52, e103–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llor, C.; Bjerrum, L. Antimicrobial resistance: Risk associated with antibiotic overuse and initiatives to reduce the problem. Ther. Adv. Drug Saf. 2014, 5, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palin, V.; Welfare, W.; Ashcroft, D.M.; van Staa, T.P. Shorter and Longer Courses of Antibiotics for Common Infections and the Association With Reductions of Infection-Related Complications Including Hospital Admissions. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevens, D.L.; Bisno, A.L.; Chambers, H.F.; Dellinger, E.P.; Goldstein, E.J.; Gorbach, S.L.; Hirschmann, J.V.; Kaplan, S.L.; Montoya, J.G.; Wade, J.C. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, e10–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shulman, S.T.; Bisno, A.L.; Clegg, H.W.; Gerber, M.A.; Kaplan, E.L.; Lee, G.; Martin, J.M.; Van Beneden, C. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Group A Streptococcal Pharyngitis: 2012 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, e86–e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, M.R.; Dagan, R.; Appelbaum, P.C.; Burch, D.J. Prevalence of Antimicrobial-Resistant Pathogens in Middle Ear Fluid: Multinational Study of 917 Children with Acute Otitis Media. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.W.; Benninger, M.S.; Brook, I.; Brozek, J.L.; Goldstein, E.J.; Hicks, L.A.; Pankey, G.A.; Seleznick, M.; Volturo, G.; Wald, E.R.; et al. IDSA Clinical Practice Guideline for Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis in Children and Adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, e72–e112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halpin, D.M.G.; Criner, G.J.; Papi, A.; Singh, D.; Anzueto, A.; Martinez, F.J.; Agusti, A.A.; Vogelmeier, C.F. Global Initiative for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. The 2020 GOLD Science Committee Report on COVID-19 and Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2021, 203, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bateman, E.D.; Hurd, S.S.; Barnes, P.J.; Bousquet, J.; Drazen, J.M.; FitzGerald, M.; Gibson, P.; Ohta, K.; O’Byrne, P.; Pedersen, S.E.; et al. Global Strategy for Asthma Management and Prevention: GINA Executive Summary. Eur. Respir. J. 2008, 31, 143–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Metlay, J.P.; Waterer, G.W.; Long, A.C.; Anzueto, A.; Brozek, J.; Crothers, K.; Cooley, L.A.; Dean, N.C.; Fine, M.J.; Flanders, S.A.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Community-acquired Pneumonia. An Official Clinical Practice Guideline of the American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 200, e45–e67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, L.C.; Gerding, D.N.; Johnson, S.; Bakken, J.S.; Carroll, K.C.; Coffin, S.E.; Dubberke, E.R.; Garey, K.W.; Gould, C.V.; Kelly, C.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA). Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 66, e1–e48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shane, A.L.; Mody, R.K.; Crump, J.A.; Tarr, P.I.; Steiner, T.S.; Kotloff, K.; Langley, J.M.; Wanke, C.; Warren, C.A.; Cheng, A.C.; et al. 2017 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Infectious Diarrhea. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2017, 65, e45–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomkin, J.S.; Mazuski, J.E.; Bradley, J.S.; Rodvold, K.A.; Goldstein, E.J.; Baron, E.J.; O’Neill, P.J.; Chow, A.W.; Dellinger, E.P.; Eachempati, S.R.; et al. Diagnosis and Management of Complicated Intra-Abdominal Infection in Adults and Children: Guidelines by the Surgical Infection Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Surg. Infect. 2010, 11, 79–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BACTRIM (Sulfamethoxazole-Trimethoprim) [Package Insert]; Mutual Pharmaceutical Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2013.

| Demographics | n = 400 |

|---|---|

| Average Age—years | 42.2 ± 19.6 |

| Age | |

| ≥65 years | 67 (16.8%) |

| 18–64 years | 333 (83.3%) |

| Female | 276 (69.0%) |

| Race | |

| Caucasian | 142 (35.5%) |

| African American | 253 (63.3%) |

| Other | 5 (1.3%) |

| Average BMI—kg/m2 | 31.4 ± 9.1 |

| Creatinine Clearance | |

| >60 mL/min | 140 (35.0%) |

| 30–60 mL/min | 43 (10.8%) |

| <30 mL/min | 19 (4.8%) |

| No lab | 198 (49.5%) |

| Temperature | |

| ≥100.4 °F | 15 (3.8%) |

| <100.4 °F | 384 (96.0%) |

| Not recorded | 1 (0.3%) |

| White Blood Cell Count | |

| >12,000 cell/mm3 | 43 (10.8%) |

| 4000–12,000 cell/mm3 | 161 (40.3%) |

| <4000 cell/mm3 | 3 (0.8%) |

| No lab | 193 (48.3%) |

| Beta-Lactam Allergy | 73 (18.3%) |

| Infection | Appropriate | Inappropriate |

|---|---|---|

| Overall | 191 (47.8%) | 209 (52.3%) |

| Urinary tract | 61 (50.0%) | 61 (50.0%) |

| Skin and soft tissue | 50 (56.8%) | 38 (43.2%) |

| Ear, nose, and throat | 15 (31.3%) | 33 (68.8%) |

| Other or mixed | 25 (56.8%) | 19 (43.2%) |

| Respiratory tract | 13 (33.3%) | 26 (66.7%) |

| Dental | 11 (44.0%) | 14 (56.0%) |

| Intra-abdominal | 9 (55.6%) | 8 (44.4%) |

| Sexually transmitted | 7 (41.2%) | 10 (58.8%) |

| Infection | n |

|---|---|

| Urinary tract | 122 (30.5%) |

| Skin and soft tissue | 88 (22.0%) |

| Ear, nose, and throat | 48 (12.0%) |

| Other or mixed | 44 (11.0%) |

| Respiratory tract | 39 (9.8%) |

| Dental | 25 (6.3%) |

| Intra-abdominal | 17 (4.3%) |

| Sexually transmitted | 17 (4.3%) |

| Infection | Total Inappropriate Prescriptions, n | Choice of Therapy | Dosing a | Not Indicated | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n | n | ||

| Overall | 209 | 72 (34.3%) | 46 (21.9%) | 32 (15.2%) | 60 (28.6%) |

| Urinary tract | 61 | 15 (24.6%) | 6 (9.8%) | 1 (1.6%) | 39 (63.9%) |

| Skin, soft tissue | 38 | 19 (50.0%) | 13 (34.2%) | 5 (13.2%) | 1 (2.6%) |

| Ear, nose, throat | 33 | 17 (51.5%) | 11 (33.3%) | 2 (6.1%) | 3 (9.1%) |

| Other or mixed | 19 | 9 (47.4%) | 4 (21.1%) | 2 (10.5%) | 4 (21.1%) |

| Respiratory tract | 26 | 7 (26.9%) | 0 | 17 (65.4%) | 2 (7.7%) |

| Dental | 14 | 1 (7.1%) | 8 (57.1%) | 0 | 5 (35.7%) |

| Intra-abdominal | 8 | 2 (25.0%) | 3 (37.5%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0 |

| Sexually transmitted | 10 | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 7 (70.0%) |

| Agent | Total Inappropriate Prescriptions, n | Choice of Therapy | Dosing b | Not Indicated | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | n | n | ||

| Amoxicillin | 27 | 6 (22.2%) | 12 (44.4%) | 3 (11.1%) | 6 (22.2%) |

| Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | 4 | 1 (25.0% | 0 | 0 | 3 (75.0%) |

| Azithromycin | 25 | 12 (48.0%) | 0 | 13 (52.0%) | 0 |

| Cefdinir | 3 | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 2 (66.7%) |

| Cefprozil | 1 | 0 | 1 (100.0%) | 0 | 0 |

| Cefuroxime | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 | 0 |

| Cephalexin | 26 | 7 (26.9%) | 13 (50.0%) | 4 (15.4%) | 2 (7.7%) |

| Ciprofloxacin | 12 | 1 (8.3%) | 0 | 1 (8.3%) | 10 (83.3%) |

| Clindamycin | 16 | 7 (43.8%) | 7 (43.8%) | 1 (6.2%) | 1 (6.2%) |

| Doxycycline | 10 | 3 (30.0%) | 1 (10.0%) | 5 (50.0%) | 1 (10.0%) |

| Levofloxacin | 7 | 5 (71.4%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0 |

| Macrobid | 17 | 5 (29.4%) | 0 | 1 (5.9%) | 11 (64.7%) |

| Macrodantin | 3 | 3 (100.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Metronidazole | 17 | 3 (17.6%) | 6 (35.3%) | 1 (5.9%) | 7 (41.2%) |

| Penicillin VK | 2 | 1 (50.0%) | 1 (50.0%) | 0 | 0 |

| Rifampin | 2 | 2 (100.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Trimethoprim-SMX | 35 | 14 (40.0%) | 2 (5.7%) | 1 (2.9%) | 18 (51.4%) |

| Subgroup | Inappropriate Prescriptions |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| ≥65 years | 38 (56.7%) |

| 18–64 years | 172 (51.7%) |

| Creatinine Clearance | |

| >60 mL/min | 68 (48.6%) |

| 30–60 mL/min | 23 (53.5%) |

| <30 mL/min | 10 (52.6%) |

| No lab | 109 (55.1%) |

| Provider | |

| Physicians | 88 (50.9%) |

| Nurse Practitioners | 107 (56.3%) |

| Physician Assistants | 15 (40.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Le, G.; Ivy, M.; Dickey, S.; Welch, R.; Stallings, D. A Study Review of the Appropriateness of Oral Antibiotic Discharge Prescriptions in the Emergency Department at a Rural Hospital in Mississippi, USA. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071186

Le G, Ivy M, Dickey S, Welch R, Stallings D. A Study Review of the Appropriateness of Oral Antibiotic Discharge Prescriptions in the Emergency Department at a Rural Hospital in Mississippi, USA. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(7):1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071186

Chicago/Turabian StyleLe, Giang, Madalyn Ivy, Sharon Dickey, Ron Welch, and Danielle Stallings. 2023. "A Study Review of the Appropriateness of Oral Antibiotic Discharge Prescriptions in the Emergency Department at a Rural Hospital in Mississippi, USA" Antibiotics 12, no. 7: 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071186

APA StyleLe, G., Ivy, M., Dickey, S., Welch, R., & Stallings, D. (2023). A Study Review of the Appropriateness of Oral Antibiotic Discharge Prescriptions in the Emergency Department at a Rural Hospital in Mississippi, USA. Antibiotics, 12(7), 1186. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12071186