Antibiotic Overprescribing among Neonates and Children Hospitalized with COVID-19 in Pakistan and the Implications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. General Outline of the Study

4.2. Study Variables

- Demographic characteristics of the study participants, including their age, gender, residence, number of days at the hospital, admission to the intensive care unit, presence of any co-morbidity, and the use of ventilation during hospital stays.

- Status of COVID-19 was documented by the investigators. A positive or confirmed COVID-19 patient is defined as a positive result on a real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay of nasal or pharyngeal swab specimens. As mentioned, suspected cases included children who were not currently testing positive; however, their parents had seen signs and symptoms of COVID-19. In addition, these children had at least one family member diagnosed with COVID-19.

- COVID-19 disease severity, categorized into asymptomatic, mild, moderate, severe and critical, as per the guidelines for the management of COVID-19 issued by the Ministry of National Health Services, Regulation, and Coordination, Government of Pakistan. Asymptomatic cases meant children were tested as positive with COVID-19; however, were currently without symptoms. Mild cases include those manifesting symptoms due to COVID-19, but without hemodynamic disturbances and X-ray abnormalities. Mild cases did not require oxygen and the oxygen saturation in mild cases must be ≥94%. Those patients that had abnormal chest X-rays, including X-rays infiltrates involving <50% of the total lung fields, oxygen saturation below 94%, but above 90%, and without any severe symptoms, were declared as moderate cases of COVID-19. Severe cases of COVID-19 included children that had a fever and cough along with respiratory rate < 30, severe respiratory distress, chest X-rays with infiltrates involving <50% of the total lung fields and oxygen saturation ≤ 90 on room air. Critical cases were those that showed a worsening of respiratory symptoms or the presence of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARSD), respiratory or cardiac failure and bilateral opacities or lung collapse on chest X-rays or CT scans.

- Signs and symptoms of COVID-19 including a fever, cough, sore throat, tachypnea, deceases level of consciousness, headache/body ache, lethargy, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and irritability, were documented from individual medical records.

- Laboratory findings, including white blood cell counts (WBCs), c-reactive protein (CRP) level, D-dimer, and serum ferritin, were recorded by the investigators in patients’ notes. X-ray findings were reviewed by the medical doctors and consulted with treating physicians in case any clarification was needed. Normal ranges of WBCs, CRP D-dimer and serum ferritin were taken from the reference mentioned in the testing kits that were available and used in the laboratories of the participating hospitals.

- Existence of bacterial co-infection and secondary bacterial infection among COVID-19 patients. Bacterial co-infection was identified as those bacterial infections identified in ≤2 days after hospital admission due to COVID-19 and bacterial secondary infection as bacterial infections identified in >2 days after admission, confirmed microbiologically.

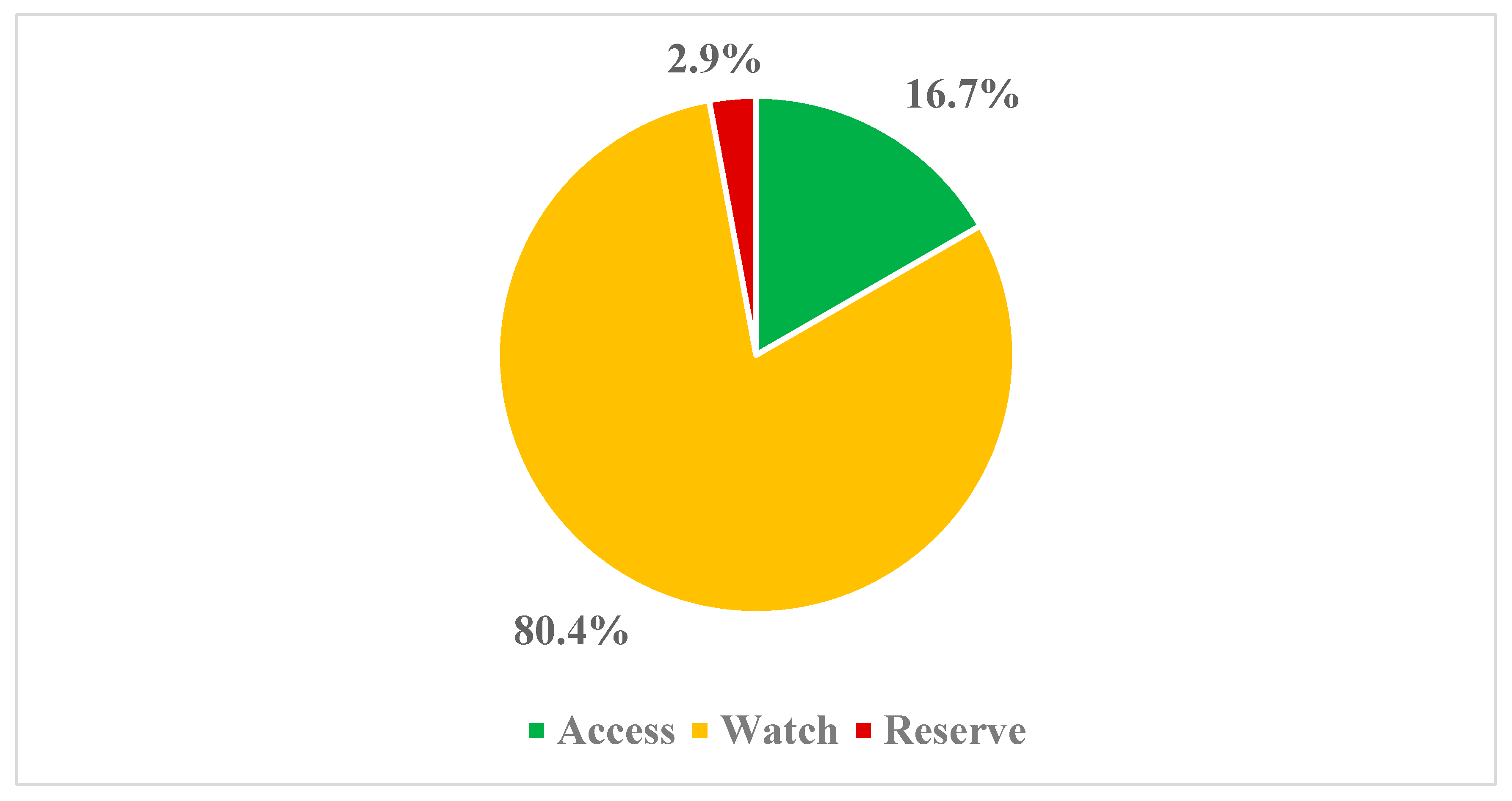

- Details about the antibiotics prescribed among hospitalized neonates and children. This included how many hospitalized COVID-19 patients were prescribed antibiotics during their stay in hospitals, as well as the existence of bacterial co-infection and bacterial secondary infections. Antibiotics were further classified according to the ATC classification, as well as the WHO AWaRe classification [60,93,94]. ‘Access’ antibiotics should typically be prescribed to treat commonly encountered infections, as they have a lower resistance potential, with those in the ‘Watch’ group ideally only prescribed in critical conditions, as they have a greater chance of resistance development. Those in the ‘Reserve’ category should only be prescribed in multi-drug resistance cases, with the aim of curbing rising AMR rates [41,60,84,94,95,96].

- The total number of antibiotics, the average number of antibiotics prescribed per patient, the duration of antibiotic therapy and the consumption of other antimicrobials. We did not specifically document the extent of prescribing of antifungals, although we are aware that there can be joint fungal and bacterial co-infections in patients in the ICU [22], as our main focus was on the extent of the prescribing of antibiotics, especially ‘Watch’ antibiotics in this population, alongside the extent of bacterial infections, including secondary bacterial infections.

- Outcomes, including whether neonates or children were discharged from a hospital or died.

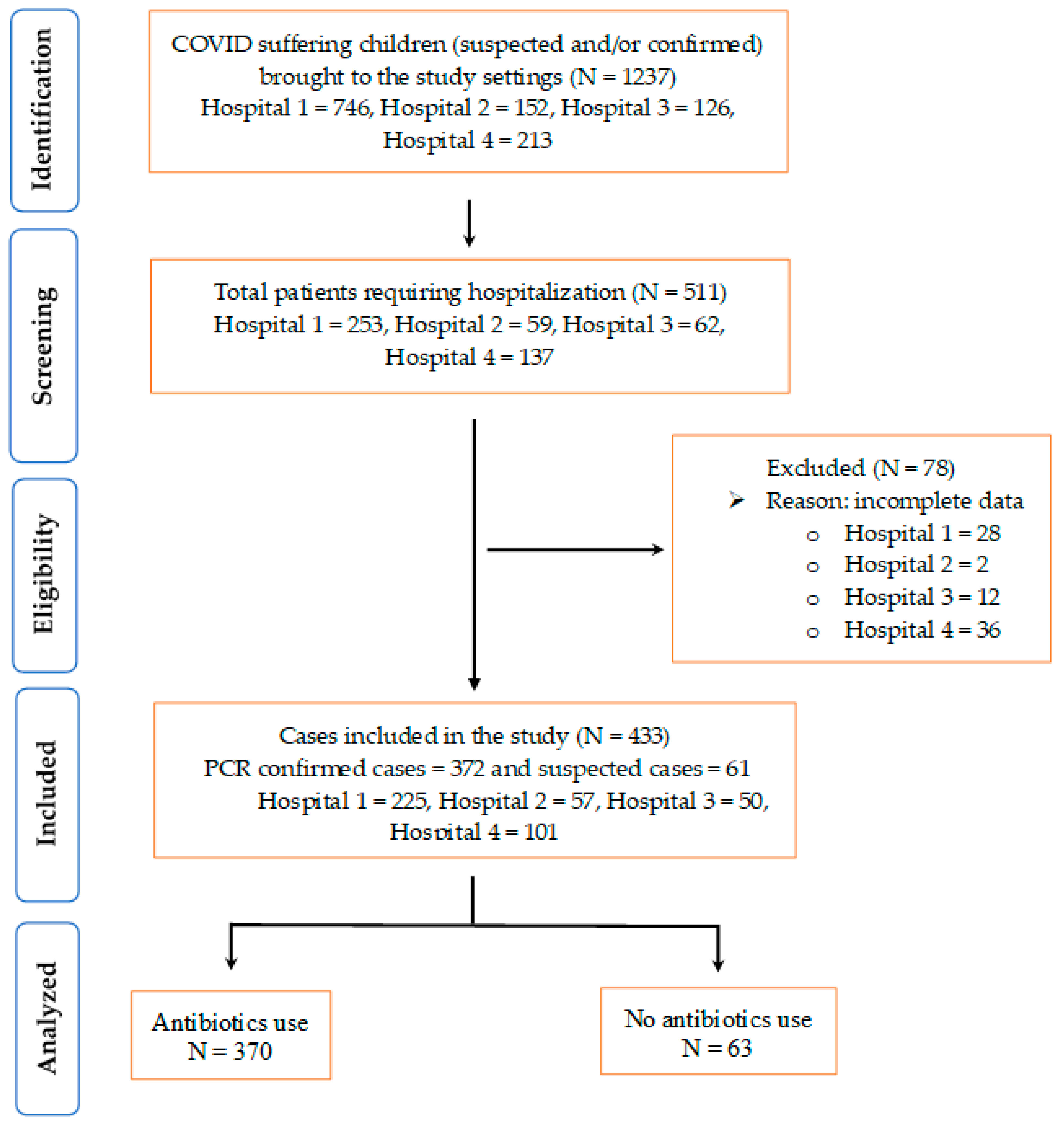

4.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria and Data Collection Procedures

4.4. Statictical Analyses

4.5. Ethical Considerations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ahmed, T.; Ilyas, M.; Yousafzai, W. COVID-19 in Children Rattles Healthcare-Hospitals in Three Major Cities Suspect Higher Number of Coronavirus Cases in Minors. 2021. Available online: https://tribune.com.pk/story/2293275/covid-19-in-children-rattles-healthcare (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- The Express Tribune. At Least 5792 Children Tested Positive for COVID-19 in Islamabad. 2021. Available online: https://tribune.com.pk/story/2292667/at-least-5792-children-tested-positive-for-covid-19-in-islamabad (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Shahid, S.; Raza, M.; Junejo, S.; Maqsood, S. Clinical features and outcome of COVID-19 positive children from a tertiary healthcare hospital in Karachi. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 5988–5997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latif, A. Pakistani Children Face 14% Mortality Risk after Catching COVID: Study. 2021. Available online: https://www.aa.com.tr/en/asia-pacific/pakistani-children-face-14-mortality-risk-after-catching-covid-study/2445719# (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Bhuiyan, M.U.; Stiboy, E.; Hassan, M.Z.; Chan, M.; Islam, M.S.; Haider, N.; Jaffe, A.; Homaira, N. Epidemiology of COVID-19 infection in young children under five years: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine 2021, 39, 667–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, T.; Guo, W.; Guo, W.; Zheng, J.; Zhang, J.; Dong, C.; Na, R.; Zheng, L.; et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of children with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). J. Med. Virol. 2020, 93, 1057–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.; Liu, S.; Chen, L.; Zhuang, L.; Zhang, J.; Xin, Y. The clinical characteristics of pediatric inpatients with SARS-CoV-2 infection: A meta-analysis and systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howard-Jones, A.R.; Bowen, A.C.; Danchin, M.; Koirala, A.; Sharma, K.; Yeoh, D.K.; Burgner, D.P.; Crawford, N.W.; Goeman, E.; Gray, P.E.; et al. COVID-19 in children: I. Epidemiology, prevention and indirect impacts. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2021, 58, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Haque, M.; Shetty, A.; Choudhary, S.; Bhatt, R.; Sinha, V.; Manohar, B.; Chowdhury, K.; Nusrat, N.; Jahan, N.; et al. Characteristics and Management of Children With Suspected COVID-19 Admitted to Hospitals in India: Implications for Future Care. Cureus 2022, 14, e27230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, K.; Haque, M.; Nusrat, N.; Adnan, N.; Islam, S.; Lutfor, A.B.; Begum, D.; Rabbany, A.; Karim, E.; Malek, A.; et al. Management of Children Admitted to Hospitals across Bangladesh with Suspected or Confirmed COVID-19 and the Implications for the Future: A Nationwide Cross-Sectional Study. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, O.; Muttalib, F.; Tang, K.; Jiang, L.; Lassi, Z.S.; Bhutta, Z. Clinical characteristics, treatment and outcomes of paediatric COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Dis. Child. 2021, 106, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefah, I.A.; Sarkodie, S.A.; Pichierri, G.; Schellack, N.; Godman, B. Assessing the Clinical Characteristics and Management of COVID-19 among Pediatric Patients in Ghana: Findings and Implications. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Khan, A.H.; Salman, M.; Sulaiman, S.A.S.; Godman, B. Antimicrobial Utilization among Neonates and Children: A Multicenter Point Prevalence Study from Leading Children’s Hospitals in Punjab, Pakistan. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantovani, A.; Rinaldi, E.; Zusi, C.; Beatrice, G.; Saccomani, M.D.; Dalbeni, A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in children and/or adolescents: A meta-analysis. Pediatr. Res. 2020, 89, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardi, P.; Esmaeili, M.; Iravani, P.; Abdar, M.E.; Pourrostami, K.; Qorbani, M. Characteristics of Children With Kawasaki Disease-Like Signs in COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 625377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahriarirad, R.; Dashti, A.S.; Ghotbabadi, S.H. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome with Features of Atypical Kawasaki Disease during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Case Rep. Pediatr. 2021, 2021, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuhara, J.; Watanabe, K.; Takagi, H.; Sumitomo, N.; Kuno, T. COVID-19 and multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 837–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, C.V.; Khaitan, A.; Kirmse, B.M.; Borkowsky, W. COVID-19 in Children: A Review and Parallels to Other Hyperinflammatory Syndromes. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 593455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Balan, S.; Rauf, A.; Kappanayil, M.; Kesavan, S.; Raj, M.; Sivadas, S.; Vasudevan, A.K.; Chickermane, P.; Vijayan, A.; et al. COVID-19 related multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C): A hospital-based prospective cohort study from Kerala, India. BMJ Paediatr. Open 2021, 5, e001195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandi, N.; Ciccarese, F.; Rimondi, M.R.; Balacchi, C.; Modolon, C.; Sportoletti, C.; Renzulli, M.; Coppola, F.; Golfieri, R. An Imaging Overview of COVID-19 ARDS in ICU Patients and Its Complications: A Pictorial Review. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewi, R.; Kaswandani, N.; Karyanti, M.R.; Setyanto, D.B.; Pudjiadi, A.H.; Hendarto, A.; Djer, M.M.; Prayitno, A.; Yuniar, I.; Indawati, W.; et al. Mortality in children with positive SARS-CoV-2 polymerase chain reaction test: Lessons learned from a tertiary referral hospital in Indonesia. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2021, 107, 78–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardi, T.; Pintado, V.; Gomez-Rojo, M.; Escudero-Sanchez, R.; Lopez, A.A.; Diez-Remesal, Y.; Castro, N.M.; Ruiz-Garbajosa, P.; Pestaña, D. Nosocomial infections associated to COVID-19 in the intensive care unit: Clinical characteristics and outcome. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2021, 40, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Tariq, S.; Iftikhar, Z.; Meyer, J.C.; Salman, M.; Mallhi, T.H.; Khan, Y.H.; Godman, B.; Seaton, R.A. Predictors and Outcomes of Healthcare-Associated Infections among Patients with COVID-19 Admitted to Intensive Care Units in Punjab, Pakistan; Findings and Implications. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Clinical Management of COVID-19: Living Guideline, 15 September 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Clinical-2022.2 (accessed on 8 February 2023).

- Ministry of National Health Services Regulations and Coordination, Government of Pakistan. Guidelines-Management of COVID19 in Children 2020. Available online: https://www.childhealthtaskforce.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/Pakistan%20Ministry%20of%20National%20Health%20Services%2C%20Management%20of%20COVID-19%20in%20Children.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2023).

- NICE. COVID-19 Rapid Guideline: Managing COVID-19. 2022. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng191/resources/covid19-rapid-guideline-managing-covid19-pdf-51035553326 (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- National Institutes of Health. COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines; Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Products. 2022. Available online: https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ (accessed on 17 January 2022).

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Soucy, J.-P.R.; Westwood, D.; Daneman, N.; MacFadden, D.R. Antibiotic prescribing in patients with COVID-19: Rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 27, 520–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaikh, F.S.; Godman, B.; Sindi, O.N.; Seaton, R.A.; Kurdi, A. Prevalence of bacterial coinfection and patterns of antibiotics prescribing in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0272375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, S.; Hasan, S.S.; Bond, S.E.; Conway, B.R.; Aldeyab, M.A. Antimicrobial consumption in patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2021, 20, 749–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, B.J.; So, M.; Raybardhan, S.; Leung, V.; Westwood, D.; MacFadden, D.R.; Soucy, J.-P.R.; Daneman, N. Bacterial co-infection and secondary infection in patients with COVID-19: A living rapid review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1622–1629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lansbury, L.; Lim, B.; Baskaran, V.; Lim, W.S. Co-infections in people with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Infect. 2020, 81, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebisi, Y.A.; Jimoh, N.D.; Ogunkola, I.O.; Uwizeyimana, T.; Olayemi, A.H.; Ukor, N.A.; Lucero-Prisno, D.E. The use of antibiotics in COVID-19 management: A rapid review of national treatment guidelines in 10 African countries. Trop. Med. Health 2021, 49, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Republic of Ghana Ministry of Health. Provisional Standard Treatment Guidelines for Novel Coronavirus Infection: COVID-19 Guidelines for Ghana. 2020. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/COVID-19-STG-JUNE-2020-1.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby, P.; Mafham, M.; Linsell, L.; Bell, J.L.; Staplin, N.; Emberson, J.R.; Wiselka, M.; Ustianowski, A.; Elmahi, E.; et al. Effect of Hydroxychloroquine in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2030–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, K.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Ikram, M.N.; Ijaz-Ul-Haq, M.; Noor, I.; Rasool, M.F.; Ishaq, H.M.; Rehman, A.U.; Hasan, S.S.; Fang, Y. Perception, Attitude, and Confidence of Physicians About Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Prescribing Among COVID-19 Patients: A Cross-Sectional Study From Punjab, Pakistan. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramzan, K.; Shafiq, S.; Raees, I.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Salman, M.; Khan, A.H.; Meyer, J.C.; Godman, B. Co-Infections, Secondary Infections, and Antimicrobial Use in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19 during the First Five Waves of the Pandemic in Pakistan; Findings and Implications. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Saleem, M.S.; Ikram, M.N.; Salman, M.; Butt, S.A.; Khan, S.; Godman, B.; Seaton, R.A. Co-infections and antimicrobial use among hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Punjab, Pakistan: Findings from a multicenter, point prevalence survey. Pathog. Glob. Health 2021, 116, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ul Mustafa, Z.; Salman, M.; Aldeyab, M.; Kow, C.S.; Hasan, S.S. Antimicrobial consumption among hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in Pakistan. SN Compr. Clin. Med. 2021, 3, 1691–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. No Time to Wait: Securing the Future from Drug-Resistant Infections. 2019. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/no-time-to-wait-securing-the-future-from-drug-resistant-infections (accessed on 10 January 2023).

- Sulis, G.; Sayood, S.; Katukoori, S.; Bollam, N.; George, I.; Yaeger, L.H.; Chavez, M.A.; Tetteh, T.; Yarrabelli, S.; Pulcini, C.; et al. Exposure to World Health Organization’s AWaRe antibiotics and isolation of multidrug resistant bacteria: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dadgostar, P. Antimicrobial Resistance: Implications and Costs. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3903–3910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Hammour, K.; Al-Heyari, E.; Allan, A.; Versporten, A.; Goossens, H.; Abu Hammour, G.; Manaseer, Q. Antimicrobial Consumption and Resistance in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Jordan: Results of an Internet-Based Global Point Prevalence Survey. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godman, B.; Egwuenu, A.; Haque, M.; Malande, O.; Schellack, N.; Kumar, S.; Saleem, Z.; Sneddon, J.; Hoxha, I.; Islam, S.; et al. Strategies to Improve Antimicrobial Utilization with a Special Focus on Developing Countries. Life 2021, 11, 528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, S.; Rahman, S.U.; Muhammad, F.; Mohsin, M. Association between antimicrobial consumption and resistance rate of Escherichia coli in hospital settings. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2023, 134, lxac003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, A. Antimicrobial Resistance: The Next Probable Pandemic. J. Nepal Med. Assoc. 2022, 60, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD Health Policy Studies. Stemming the Superbug Tide. 2018. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/9789264307599-en/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/9789264307599-en&mimeType=text/html (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Cassini, A.; Högberg, L.D.; Plachouras, D.; Quattrocchi, A.; Hoxha, A.; Simonsen, G.S.; Colomb-Cotinat, M.; Kretzschmar, M.E.; Devleesschauwer, B.; Cecchini, M.; et al. Attributable deaths and disability-adjusted life-years caused by infections with antibiotic-resistant bacteria in the EU and the European Economic Area in 2015: A population-level modelling analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2019, 19, 56–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Bornman, C.; Zafer, M.M. Antimicrobial Resistance Threats in the emerging COVID-19 pandemic: Where do we stand? J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, J. How COVID-19 is accelerating the threat of antimicrobial resistance. BMJ 2020, 369, m1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwu, C.J.; Jordan, P.; Jaja, I.F.; Iwu, C.D.; Wiysonge, C.S. Treatment of COVID-19: Implications for antimicrobial resistance in Africa. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2020, 35, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, E.Y.; Van Boeckel, T.P.; Martinez, E.M.; Pant, S.; Gandra, S.; Levin, S.A.; Goossens, H.; Laxminarayan, R. Global increase and geographic convergence in antibiotic consumption between 2000 and 2015. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E3463–E3470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullah, I.; Javaid, A.; Tahir, Z.; Ullah, O.; Shah, A.A.; Hasan, F.; Ayub, N. Pattern of Drug Resistance and Risk Factors Associated with Development of Drug Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Pakistan. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.H.; Saleem, A.; Javed, S.O.; Ullah, I.; Rehman, M.U.; Islam, N.; Tahir, M.N.; Malik, T.; Hafeez, S.; Misbah, S. Rising XDR-Typhoid Fever Cases in Pakistan: Are We Heading Back to the Pre-antibiotic Era? Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 794868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Mukhtar, S.; Sarwar, S.; Naseem, M.; Malik, I.; Mushtaq, A. Drug resistance patterns, treatment outcomes and factors affecting unfavourable treatment outcomes among extensively drug resistant tuberculosis patients in Pakistan; a multicentre record review. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 462–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bilal, H.; Khan, M.N.; Rehman, T.; Hameed, M.F.; Yang, X. Antibiotic resistance in Pakistan: A systematic review of past decade. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, F.; Khan, Z.; Sohail, M.; Tahir, A.; Tipu, I.; Murtaza Saleem, H.G. Antibiotic Resistance Pattern of Acinetobacter Baumannii Isolated From Bacteremia Patients in Pakistan. J. Ayub Med. Coll. Abbottabad. 2022, 34, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Javaid, N.; Sultana, Q.; Rasool, K.; Gandra, S.; Ahmad, F.; Chaudhary, S.U.; Mirza, S. Trends in antimicrobial resistance amongst pathogens isolated from blood and cerebrospinal fluid cultures in Pakistan (2011–2015): A retrospective cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharland, M.; Zanichelli, V.; Ombajo, L.A.; Bazira, J.; Cappello, B.; Chitatanga, R.; Chuki, P.; Gandra, S.; Getahun, H.; Harbarth, S.; et al. The WHO essential medicines list AWaRe book: From a list to a quality improvement system. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2022, 28, 1533–1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deville, J.G.; Song, E.; Ouellette, C.P. COVID-19: Clinical Manifestations and Diagnosis in Children. 2023. Available online: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/covid-19-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis-in-children# (accessed on 8 January 2023).

- Dona, D.; Montagnani, C.; Di Chiara, C.; Venturini, E.; Galli, L.; Lo Vecchio, A.; Denina, M.; Olivini, N.; Bruzzese, E.; Campana, A.; et al. COVID-19 in Infants Less than 3 Months: Severe or Not Severe Disease? Viruses 2022, 14, 2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Mehdizadeh, M.; Badv, R.S.; Navaeian, A.; Pourakbari, B.; Rostamyan, M.; Ekbatani, M.S.; Eshaghi, H.; Abdolsalehi, M.R.; Alimadadi, H.; et al. The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Children: A Study in an Iranian Children’s Referral Hospital. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 2649–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preston, L.E.; Chevinsky, J.R.; Kompaniyets, L.; Lavery, A.M.; Kimball, A.; Boehmer, T.K.; Goodman, A.B. Characteristics and Disease Severity of US Children and Adolescents Diagnosed With COVID-19. JAMA Netw. Open 2021, 4, e215298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaiba, L.A.; Altirkawi, K.; Hadid, A.; Alsubaie, S.; Alharbi, O.; Alkhalaf, H.; Alharbi, M.; Alruqaie, N.; Alzomor, O.; Almughaileth, F.; et al. COVID-19 Disease in Infants Less Than 90 Days: Case Series. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 674899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, A.A.; Dargham, S.R.; Loka, S.; Shaik, R.M.; Chemaitelly, H.; Tang, P.; Hasan, M.R.; Coyle, P.V.; Yassine, H.M.; Al-Khatib, H.A.; et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 Disease Severity in Children Infected with the Omicron Variant. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, e361–e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guner Ozenen, G.; Sahbudak Bal, Z.; Umit, Z.; Bilen, N.M.; Yildirim Arslan, S.; Yurtseven, A.; Saz, E.U.; Burcu, B.; Sertoz, R.; Kurugol, Z.; et al. Demographic, clinical, and laboratory features of COVID-19 in children: The role of mean platelet volume in predicting hospitalization and severity. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 3227–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitano, T.; Kitano, M.; Krueger, C.; Jamal, H.; Al Rawahi, H.; Lee-Krueger, R.; Sun, R.D.; Isabel, S.; García-Ascaso, M.T.; Hibino, H.; et al. The differential impact of pediatric COVID-19 between high-income countries and low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review of fatality and ICU admission in children worldwide. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0246326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, S.P.; Solomon, S.; Stachel, A.; Shust, G.F.; Clouser, K.N.; Bhavsar, S.M.; Lighter, J. Hospital and ICU Admission Risk Associated with Comorbidities Among Children with COVID-19 Ancestral Strains. Clin. Pediatr. 2023, 00099228221150605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.L.; Harwood, R.; Smith, C.; Kenny, S.; Clark, M.; Davis, P.J.; Draper, E.S.; Hargreaves, D.; Ladhani, S.; Linney, M.; et al. Risk factors for PICU admission and death among children and young people hospitalized with COVID-19 and PIMS-TS in England during the first pandemic year. Nat. Med. 2021, 28, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera-Alonso, D.; Epalza, C.; Sanz-Santaeufemia, F.J.; Grasa, C.; Villanueva-Medina, S.; Pérez, S.M.; Hernández, E.C.; Urretavizcaya-Martínez, M.; Pino, R.; Gómez, M.N.; et al. Antibiotic Prescribing in Children Hospitalized With COVID-19 and Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Spain: Prevalence, Trends, and Associated Factors. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. Soc. 2022, 11, 225–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, W.; Yu, J.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Z. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in children compared with adults in Shandong Province, China. Infection 2020, 48, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taheri, L.; Gheiasi, S.F.; Taher, M.; Basirinezhad, M.H.; Shaikh, Z.A.; Dehghan Nayeri, N. Clinical Features of COVID-19 in Newborns, Infants, and Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Compr. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2021, 45, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, H.; Allende-López, A.; Morales-Ruíz, P.; Miranda-Novales, G.; Villasis-Keever, M.; COVID-19 in Neonates with Positive RT-PCR Test. Systematic Review. Arch. Med. Res. 2022, 53, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spoulou, V.; Noni, M.; Koukou, D.; Kossyvakis, A.; Michos, A. Clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in neonates and young infants. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2021, 180, 3041–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jaegere, T.M.H.; Krdzalic, J.; Fasen, B.; Kwee, R.M. Radiological Society of North America Chest CT Classification System for Reporting COVID-19 Pneumonia: Interobserver Variability and Correlation with Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction. Radiol. Cardiothorac. Imaging 2020, 2, e200213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yock-Corrales, A.; Lenzi, J.; Ulloa-Gutiérrez, R.; Gómez-Vargas, J.; Antúnez-Montes, O.Y.; Aida, J.A.R.; del Aguila, O.; Arteaga-Menchaca, E.; Campos, F.; Uribe, F.; et al. High rates of antibiotic prescriptions in children with COVID-19 or multisystem inflammatory syndrome: A multinational experience in 990 cases from Latin America. Acta Paediatr. 2021, 110, 1902–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Z.; Hassali, M.A.; Hashmi, F.K. Pakistan’s national action plan for antimicrobial resistance: Translating ideas into reality. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 1066–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Z.; Godman, B.; Azhar, F.; Kalungia, A.C.; Fadare, J.; Opanga, S.; Markovic-Pekovic, V.; Hoxha, I.; Saeed, A.; Al-Gethamy, M.; et al. Progress on the national action plan of Pakistan on antimicrobial resistance (AMR): A narrative review and the implications. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2021, 20, 71–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siachalinga, L.; Mufwambi, W.; Lee, L.-H. Impact of antimicrobial stewardship interventions to improve antibiotic prescribing for hospital inpatients in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hosp. Infect. 2022, 129, 124–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, M.R.; Isemin, N.U.; Udoh, A.E.; Ashiru-Oredope, D. Implementation of antimicrobial stewardship programmes in African countries: A systematic literature review. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2020, 22, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, J.A.; Vlieghe, E.; Mendelson, M.; Wertheim, H.; Ndegwa, L.; Villegas, M.V.; Gould, I.; Hara, G.L. Antibiotic stewardship in low- and middle-income countries: The same but different? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2017, 23, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saleem, Z.; Godman, B.; Cook, A.; Khan, M.A.; Campbell, S.M.; Seaton, R.A.; Siachalinga, L.; Haseeb, A.; Amir, A.; Kurdi, A.; et al. Ongoing Efforts to Improve Antimicrobial Utilization in Hospitals among African Countries and Implications for the Future. Antibiotics 2022, 11, 1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. The WHO AWaRe (Access, Watch, Reserve) Antibiotic Book. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240062382 (accessed on 1 February 2023).

- Hussain, M.; Al Mamun, M.A. COVID-19 in children in Bangladesh: Situation analysis. Asia Pac. J. Paediatr. Child Health 2020, 3, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Saleem, Z.; Haseeb, A.; Godman, B.; Batool, N.; Altaf, U.; Ahsan, U.; Khan, F.U.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Nadeem, M.U.; Farrukh, M.J.; et al. Point Prevalence Survey of Antimicrobial Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic among Different Hospitals in Pakistan: Findings and Implications. Antibiotics 2022, 12, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Salman, M.; Yasir, M.; Godman, B.; Majeed, H.A.; Kanwal, M.; Iqbal, M.; Riaz, M.B.; Hayat, K.; Hasan, S.S. Antibiotic consumption among hospitalized neonates and children in Punjab province, Pakistan. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2021, 20, 931–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Majeed, H.K.; Latif, S.; Salman, M.; Hayat, K.; Mallhi, T.H.; Khan, Y.H.; Khan, A.H.; Abubakar, U.; Sultana, K.; et al. Adherence to Infection Prevention and Control Measures Among Health-Care Workers Serving in COVID-19 Treatment Centers in Punjab, Pakistan. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2023, 17, e298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamran, S.H.; Mustafa, Z.U.; Rao, A.Z.; Hasan, S.S.; Zahoor, F.; Sarwar, M.U.; Khan, S.; Butt, S.; Rameez, M.; Abbas, M.A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection pattern, transmission and treatment: Multi-center study in low to middle-income districts hospitals in Punjab, Pakistan. Pak. J. Pharm. Sci. 2021, 34, 1135–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Mustafa, Z.U.; Kow, C.S.; Salman, M.; Kanwal, M.; Riaz, M.B.; Parveen, S.; Hasan, S.S. Pattern of medication utilization in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in three District Headquarters Hospitals in the Punjab province of Pakistan. Explor. Res. Clin. Soc. Pharm. 2021, 5, 100101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Government of Pakistan. Ministry Of National Health Services, Regulations and Coordination. In Clinical Management Guidelines for COVID-19 Infections; 2020. Available online: https://nhsrc.gov.pk/SiteImage/Misc/files/20200704%20Clinical%20Management%20Guidelines%20for%20COVID-19%20infections_1203.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2023).

- Godman, B.; Haque, M.; Islam, S.; Iqbal, S.; Urmi, U.L.; Kamal, Z.M.; Shuvo, S.A.; Rahman, A.; Kamal, M.; Haque, M.; et al. Rapid Assessment of Price Instability and Paucity of Medicines and Protection for COVID-19 Across Asia: Findings and Public Health Implications for the Future. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 585832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) Classification. 2021. Available online: https://www.who.int/tools/atc-ddd-toolkit/atc-classification (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Hsia, Y.; Lee, B.R.; Versporten, A.; Yang, Y.; Bielicki, J.; Jackson, C.; Newland, J.; Goossens, H.; Magrini, N.; Sharland, M.; et al. Use of the WHO Access, Watch, and Reserve classification to define patterns of hospital antibiotic use (AWaRe): An analysis of paediatric survey data from 56 countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2019, 7, e861–e871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharland, M.; Pulcini, C.; Harbarth, S.; Zeng, M.; Gandra, S.; Mathur, S.; Magrini, N. Classifying antibiotics in the WHO Essential Medicines List for optimal use—Be AWaRe. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 18–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, E.Y.; Milkowska-Shibata, M.; Tseng, K.K.; Sharland, M.; Gandra, S.; Pulcini, C.; Laxminarayan, R. Assessment of WHO antibiotic consumption and access targets in 76 countries, 2000–15: An analysis of pharmaceutical sales data. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 21, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Godman, B.; Momanyi, L.; Opanga, S.; Nyamu, D.; Oluka, M.; Kurdi, A. Antibiotic prescribing patterns at a leading referral hospital in Kenya: A point prevalence survey. J. Res. Pharm. Pract. 2019, 8, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoth, C.; Opanga, S.; Okalebo, F.; Oluka, M.; Kurdi, A.; Godman, B. Point prevalence survey of antibiotic use and resistance at a referral hospital in Kenya: Findings and implications. Hosp. Pract. 2018, 46, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlamini, N.N.; Meyer, J.C.; Kruger, D.; Kurdi, A.; Godman, B.; Schellack, N. Feasibility of using point prevalence surveys to assess antimicrobial utilisation in public hospitals in South Africa: A pilot study and implications. Hosp. Pract. 2019, 47, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skosana, P.; Schellack, N.; Godman, B.; Kurdi, A.; Bennie, M.; Kruger, D.; Meyer, J. A point prevalence survey of antimicrobial utilisation patterns and quality indices amongst hospitals in South Africa; findings and implications. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2021, 19, 1353–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, Z.; Hassali, M.A.; Versporten, A.; Godman, B.; Hashmi, F.K.; Goossens, H.; Saleem, F. A multicenter point prevalence survey of antibiotic use in Punjab, Pakistan: Findings and implications. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2019, 17, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurdi, A.; Hasan, A.J.; Baker, K.I.; Seaton, R.A.; Ramzi, Z.S.; Sneddon, J.; Godman, B. A multicentre point prevalence survey of hospital antibiotic prescribing and quality indices in the Kurdistan regional government of Northern Iraq: The need for urgent action. Expert Rev. Anti-Infect. Ther. 2020, 19, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Number of patients per hospital | |

| H1 | 225 (52.0) |

| H2 | 57 (13.2) |

| H3 | 50 (11.5) |

| H4 | 101 (23.3) |

| Age | |

| Neonate (1–28 days) | 17 (3.9) |

| Infant (1–12 months) | 75 (17.3) |

| Toddler (1–5 years) | 146 (33.7) |

| Child (5–12 years) | 195 (45.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 275 (63.5) |

| Female | 158 (36.5) |

| Residence | |

| Rural | 125 (28.9) |

| Urban | 308 (71.1) |

| Comorbidity (including low birth weight, preterm and anemia) | |

| Yes | 44 (10.2) |

| No | 389 (89.8) |

| COVID status | |

| Positive | 372 (85.9) |

| Suspected | 61 (14.1) |

| Severity of COVID-19 (N = 372) | |

| Asymptomatic | 18 (4.8) |

| Mild | 80 (21.5) |

| Moderate | 100 (26.9) |

| Severe | 142 (38.2) |

| Critical | 32 (8.6) |

| ICU admission | |

| Yes | 162 (37.4) |

| No | 271 (62.6) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | |

| Yes | 12 (2.8) |

| No | 421 (97.2) |

| Signs and symptoms | 402 (92.8) |

| Tachypnea | 269 (62.1) |

| Decreased level of consciousness | 117 (27.0) |

| Cough | 286 (66.1) |

| Fever | 311 (71.8) |

| Sore throat | 216 (30.5) |

| Headache/body aches | 132 (30.5) |

| Lethargy | 160 (37.0) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 191 (44.1) |

| Diarrhea | 76 (11.3) |

| Others | 49 (11.3) |

| Lab and other findings | |

| Positive imaging findings | 351 (81.1) |

| Elevated WBCs | 282 (65.1) |

| Elevated CRP | 164 (37.9) |

| Elevated D-dimer | 93 (21.5) |

| Elevated ferritin | 55 (12.7) |

| Bacterial culture testing | 28 (6.5) |

| Length of stay | |

| ≤7 days | 112 (25.9) |

| 8–14 days | 227 (52.4) |

| 15–21 days | 74 (17.1) |

| >21 days | 20 (4.6) |

| Variables | N (%) |

|---|---|

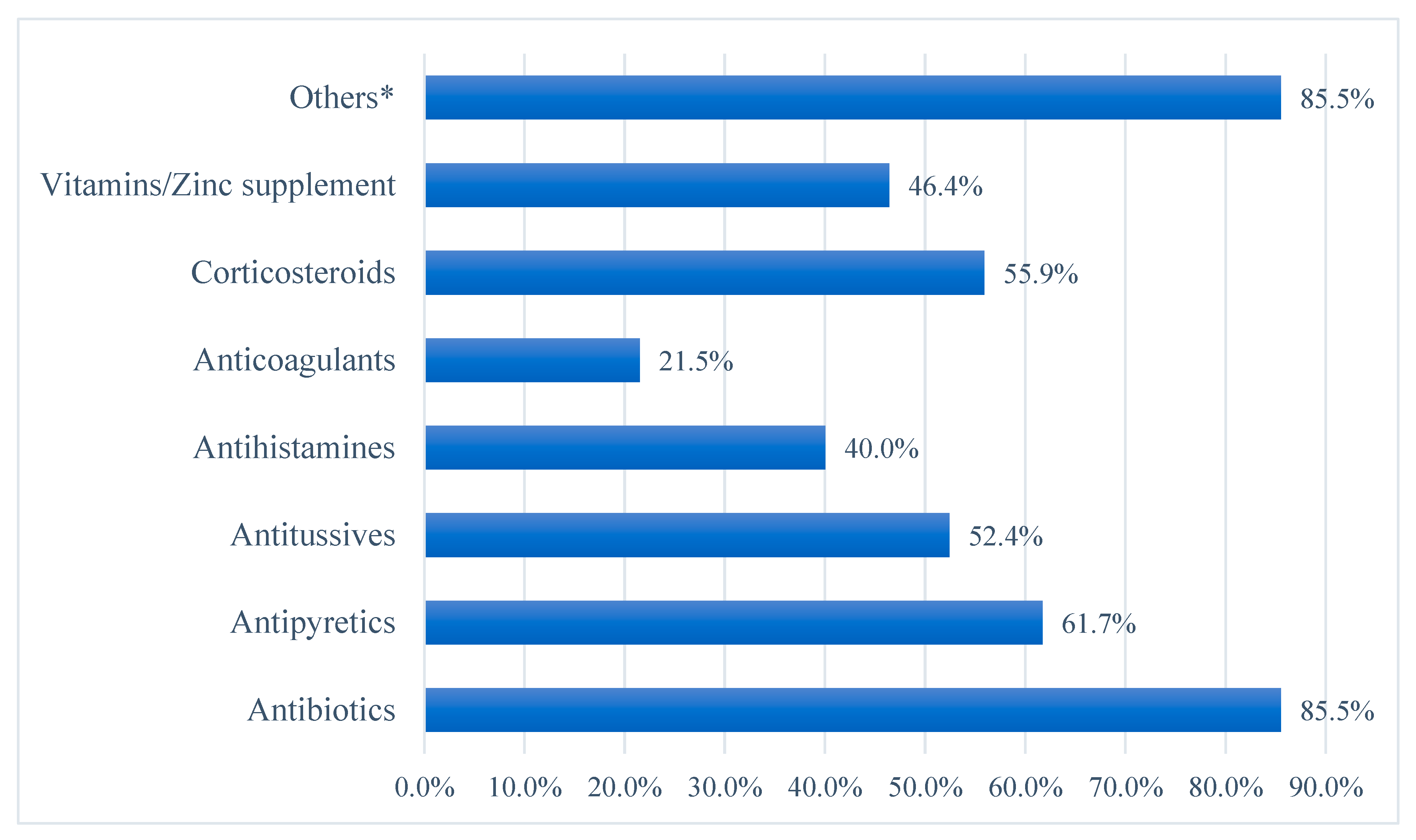

| Neonates and children prescribed antibiotics | |

| Yes | 370 (85.5) |

| No | 63 (14.5) |

| Total number of antibiotics prescribed to all the children prescribed antibiotics (N = 370) | 736 |

| Average antibiotics prescribed per patient (Mean ± SD) | 1.70 ± 0.98 |

| Number of antibiotics prescribed per patients (N = 370) | |

| One | 92 (24.9) |

| Two | 201 (54.3) |

| Three or more | 77 (20.8) |

| Route of antibiotic therapy (N = 736) | |

| Intravenous | 556 (75.5) |

| Oral | 180 (24.5) |

| Duration of antibiotic therapy | |

| ≤5 days | 423 (57.5) |

| 6–10 days | 290 (39.4) |

| >10 days | 23 (3.1) |

| ATC Class | Subclass | Name of the Antibiotic and ATC Class | AWaRe Class | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-lactam antibacterials, penicillins (J01C) | Penicillins with extended spectrum (J01CA) | Amoxicillin (J01CA04) | Access | 2 |

| Ampicillin (J01CA01) | Access | 11 | ||

| Co-amoxiclav (J01CR02) | Access | 40 | ||

| Combinations of penicillins, including beta-lactamase inhibitors (J01CR) | Piperacillin + Tazobactam (J01CR05) | Watch | 32 | |

| Other beta-lactam antibacterials (J01D) | Carbapenems (J01DH) | Meropenem (J01DH02) | Watch | 74 |

| Third-generation cephalosporins (J01DD) | Ceftriaxone (J01DD04) | Watch | 173 | |

| Ceftazidime (J01DD02) | Watch | 19 | ||

| Cephoperazone (J01DD12) | Watch | 12 | ||

| Cefotaxime (J01DD01) | Watch | 16 | ||

| Cefixime (J01DD08) | Watch | 2 | ||

| Fourth-generation cephalosporins (J01DE) | Cefepime (J01DE01) | Watch | 35 | |

| Macrolides, lincosamides and streptogramins (J01F) | Macrolides (J01FA) | Azithromycin (J01FA10) | Watch | 183 |

| Clarithromycin (J01FA09) | Watch | 5 | ||

| Quinolone antibacterials (J01M) | Fluoroquinolones (J01MA) | Ciprofloxacin (J01MA02) | Watch | 11 |

| Levofloxacin (J01MA12) | Watch | 3 | ||

| Moxifloxacin (J01MA14) | Watch | 2 | ||

| Aminoglycoside antibacterials (J01G) | Other aminoglycosides (J01GB) | Amikacin (J01GB06) | Access | 60 |

| Other antibacterials (J01X) | Glycopeptide antibacterials (J01XA) | Vancomycin (J01XA01) | Watch | 25 |

| Imidazole derivatives (J01XD) | Metronidazole (J01XD01) | Access | 10 | |

| Other antibacterials (J01XX) | Linezolid (J01XX08) | Reserve | 21 |

| Variables | No. of Antibiotics | p-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Hospitals | ||

| H1 | 1.81 ± 0.95 | 0.001 |

| H2 | 2.11 ± 0.77 | |

| H3 | 1.44 ± 1.03 | |

| H4 | 1.35 ± 1.00 | |

| Age | ||

| Neonate (1–28 days) | 1.53 ± 0.80 | 0.483 |

| Infant (1–12 months) | 1.69 ± 1.01 | |

| Toddler (1–5 years) | 1.79 ± 1.00 | |

| Child (5–12 years) | 1.65 ± 0.97 | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 1.70 ± 1.01 | 0.954 |

| Female | 1.70 ± 0.94 | |

| Residence | ||

| Rural | 1.71 ± 0.97 | 0.869 |

| Urban | 1.69 ± 0.98 | |

| Comorbidity | ||

| Yes | 1.84 ± 1.12 | 0.314 |

| No | 1.68 ± 0.96 | |

| COVID status | ||

| Positive | 1.76 ± 0.98 | 0.002 |

| Suspected | 1.34 ± 0.89 | |

| Severity of COVID (N = 372) | ||

| Asymptomatic | 0.44 ± 0.78 | <0.001 |

| Mild | 1.05 ± 1.11 | |

| Moderate | 1.68 ± 0.68 | |

| Severe | 2.16 ± 0.65 | |

| Critical | 2.72 ± 0.81 | |

| ICU admission | ||

| Yes | 2.22 ± 0.71 | <0.001 |

| No | 1.39 ± 0.99 | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | ||

| Yes | 2.67 ± 0.65 | <0.001 |

| No | 1.67 ± 0.97 | |

| X-ray abnormalities | ||

| Yes | 1.83 ± 1.88 | <0.001 |

| No | 1.12 ± 1.17 | |

| Elevated WBCs | ||

| Yes | 1.95 ± 0.86 | <0.001 |

| No | 1.23 ± 1.02 | |

| Elevated CRP | ||

| Yes | 2.19 ± 0.74 | <0.001 |

| No | 1.41 ± 0.99 | |

| Elevated D-dimer | ||

| Yes | 2.16 ± 0.74 | <0.001 |

| No | 1.57 ± 1.00 | |

| Elevated ferritin | ||

| Yes | 2.22 ± 0.81 | <0.001 |

| No | 1.62 ± 0.98 | |

| Bacterial culture testing | ||

| Yes | 1.96 ± 0.84 | 0.098 |

| No | 1.68 ± 0.99 | |

| Length of stay | ||

| ≤7 days | 1.04 ± 1.03 | <0.001 |

| 8–14 days | 1.73 ± 0.81 | |

| 15–21 days | 2.28 ± 0.73 | |

| >21 days | 2.95 ± 0.39 |

| Comparison | Mean Difference | Standard Error | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital | |||

| H1 vs. H2 | −0.29 | 0.12 | 0.078 |

| H1 vs. H3 | 0.37 | 0.16 | 0.098 |

| H1 vs. H4 | 0.47 | 0.12 | 0.001 |

| H2 vs. H3 | 0.67 | 0.18 | 0.002 |

| H2 vs. H4 | 0.76 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| H3 vs. H4 | 0.09 | 0.18 | 0.952 |

| COVID-19 severity | |||

| Asymptomatic vs. mild | −0.61 | 0.22 | 0.072 |

| Asymptomatic vs. moderate | −1.24 | 0.20 | <0.001 |

| Asymptomatic vs. severe | −1.72 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Asymptomatic vs. critical | −2.27 | 0.23 | <0.001 |

| Mild vs. moderate | −0.63 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Mild vs. severe | −1.11 | 0.14 | <0.001 |

| Mild vs. critical | −1.67 | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Moderate vs. severe | −0.48 | 0.09 | <0.001 |

| Moderate vs. critical | −1.04 | 0.16 | <0.001 |

| Severe vs. critical | −0.56 | 0.15 | 0.007 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | |||

| ≤7 vs. 8–14 | −0.69 | 0.11 | <0.001 |

| ≤7 vs. 15–21 | −1.25 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| ≤7 vs. >21 | −1.91 | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| 8–14 vs. 15–21 | −0.56 | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| 8–14 vs. >21 | −1.22 | 0.10 | <0.001 |

| 15–21 vs. >21 | −0.67 | 0.12 | <0.001 |

| Coefficients a,b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardized Coefficients | Standardized Coefficients | T | Sig. | 95% CI for B | ||

| B | SE | Beta | Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||

| (Constant) | 0.010 | 0.149 | 0.068 | 0.946 | −0.282 | 0.302 | |

| COVID-19 severity | 0.404 | 0.044 | 0.427 | 9.226 | <0.001 | 0.318 | 0.490 |

| Length of hospital stay | 0.370 | 0.058 | 0.293 | 6.325 | <0.001 | 0.255 | 0.485 |

| Hospital | −0.157 | 0.030 | −0.204 | −5.185 | <0.001 | −0.217 | −0.098 |

| Pathogen | N | Sensitivity Results |

|---|---|---|

| S. pneumonia | 3 | Linezolid, levofloxacin, vancomycin |

| P. aeruginosa | 4 | Ceftriaxone, carbapenems |

| P. aeruginosa | 2 | Ceftriaxone, carbapenems, aminoglycosides |

| P. aeruginosa | 3 | Meropenem |

| K. pneumoniae | 2 | Pipericillin, ceftazidime, meropenem |

| E. coli | 1 | Pipericillin, metronidazole |

| S. aureus | 1 | Levofloxacin, imipenem |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mustafa, Z.U.; Khan, A.H.; Harun, S.N.; Salman, M.; Godman, B. Antibiotic Overprescribing among Neonates and Children Hospitalized with COVID-19 in Pakistan and the Implications. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040646

Mustafa ZU, Khan AH, Harun SN, Salman M, Godman B. Antibiotic Overprescribing among Neonates and Children Hospitalized with COVID-19 in Pakistan and the Implications. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(4):646. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040646

Chicago/Turabian StyleMustafa, Zia UI, Amer Hayat Khan, Sabariah Noor Harun, Muhammad Salman, and Brian Godman. 2023. "Antibiotic Overprescribing among Neonates and Children Hospitalized with COVID-19 in Pakistan and the Implications" Antibiotics 12, no. 4: 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040646

APA StyleMustafa, Z. U., Khan, A. H., Harun, S. N., Salman, M., & Godman, B. (2023). Antibiotic Overprescribing among Neonates and Children Hospitalized with COVID-19 in Pakistan and the Implications. Antibiotics, 12(4), 646. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12040646