Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Experiences and Views of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis and Meta-Ethnography

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

2.2. Screening

2.3. Quality Assessment

2.4. Data Extraction (Selection and Coding)

2.5. Translation and Synthesis

2.6. Reviewers’ Reflexivity

3. Results

3.1. GRADE-CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research

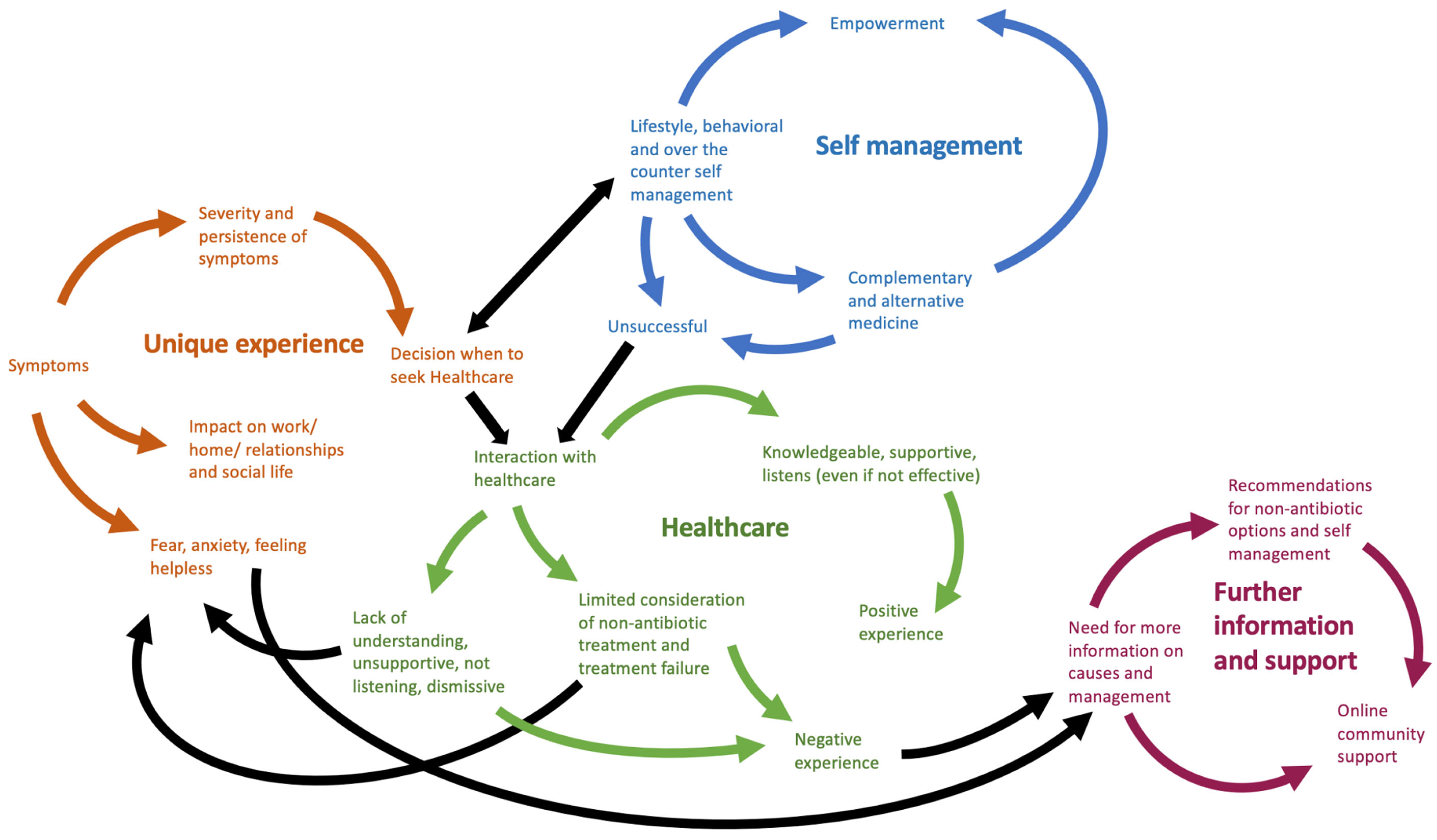

3.2. Women with rUTIs

- 1.

- Most women describe a long history of rutis, with variability of frequency, severity, symptoms, and ability to self-diagnose

- 2.

- Various factors are described as triggers for ruti, and patients worry about a serious underlying cause

- 3.

- UTIs generally have significant and widespread effects on women’s quality-of-life

- 4.

- Women with rutis commonly use self-help, lifestyle, and complementary and alternative medicine (cam) options to try to treat and prevent UTIs.

- 5.

- The effectiveness of antibiotics varied, and patients are concerned about their use

- 6.

- Women with rUTIs seek healthcare for most, but not all, UTIs. they describe anger and frustration with healthcare in terms of their care, the use of antibiotics, and an underestimation of the impact of rUTIs

- 7.

- Women sought information and support from a variety of sources and feel that more information and research is needed

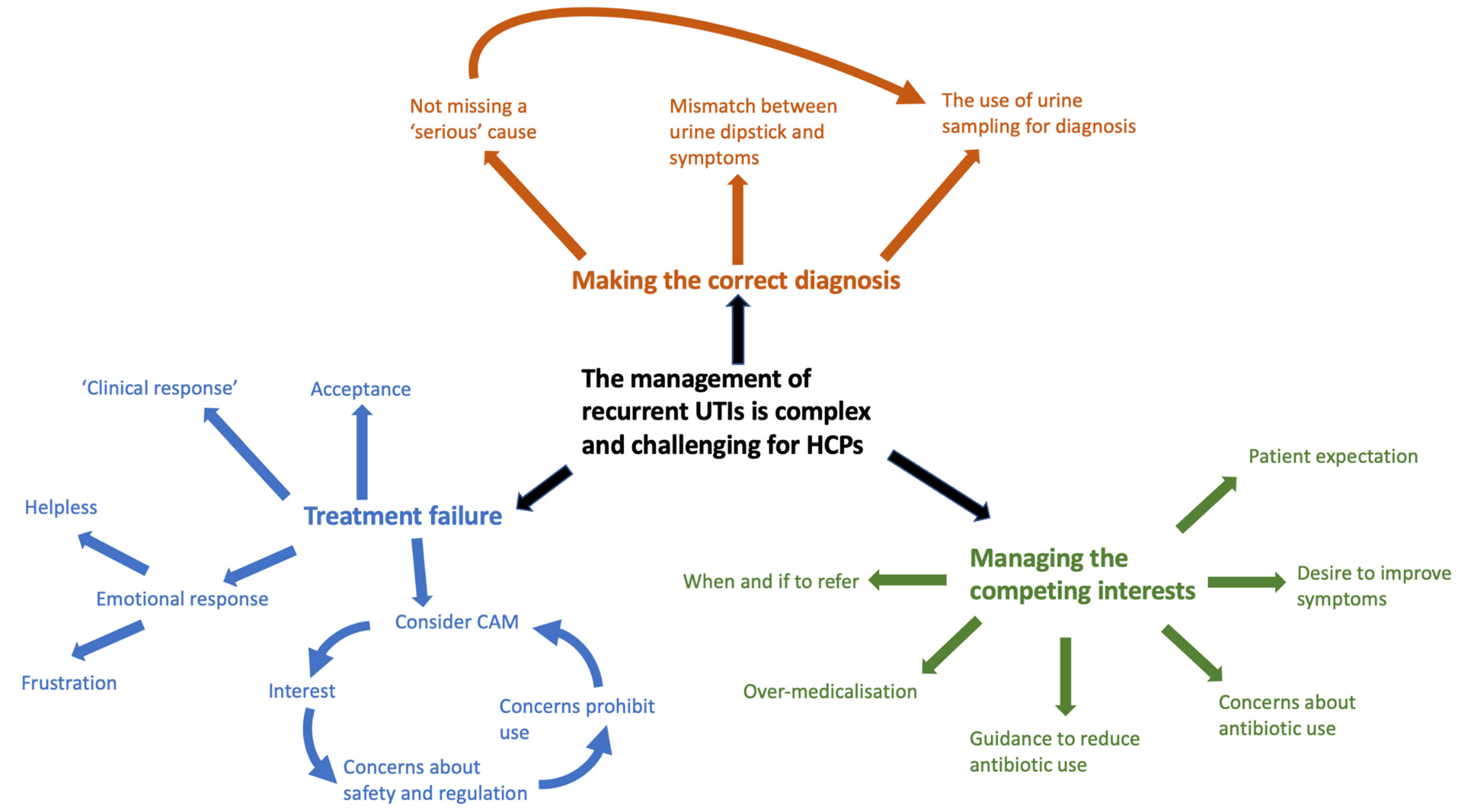

3.3. Healthcare Professionals

- There are differences in the use of, and reason for, conducting urine cultures

- 2.

- Making the correct diagnosis is important, and HCPs worry about missing serious disease

- 3.

- HCPs appreciate that rUTIs have a significant impact on quality-of-life

- 4.

- HCPs believe self-help measures are important to prevent UTI recurrence

- 5.

- Some HCPs are interested in the use of CAMs but have significant concerns about their use and admit a lack of knowledge about them

- 6.

- HCPs feel antibiotics are effective short term but are concerned about their use

- 7.

- Attitudes toward when to refer to secondary care and its benefits varied amongst HCPs

- 8.

- HCPs must consider and balance several competing interests when managing rUTIs

3.4. Conceptual Model Development

4. Discussion

4.1. Comparison with the Existing Literature

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

4.3. Clinical Implications and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Glossary

References

- Butler, C.C.; Hawking, M.K.D.; Quigley, A.; McNulty, C.A.M. Incidence, severity, help seeking, and management of uncomplicated urinary tract infection: A population-based survey. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2015, 65, e702–e707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leydon, G.M.; Turner, S.; Smith, H.; Little, P. Women’s views about management and cause of urinary tract infection: Qualitative interview study. BMJ 2010, 340, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leydon, G.M.; Turner, S.; Smith, H.; Little, P. The journey from self-care to GP care: A qualitative interview study of women presenting with symptoms of urinary tract infection. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2009, 59, 490–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malterud, K.; Bærheim, A. Peeing barbed wire: Symptom experiences in women with lower urinary tract infection. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 1999, 17, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Flower, A.; Bishop, F.L.; Lewith, G. How women manage recurrent urinary tract infections: An analysis of postings on a popular web forum. BMC Fam. Pract. 2014, 15, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, A.K.; Verma, S. Quality of Life in Women with Urinary Tract Infections: Is Benign Disease a Misnomer? J. Am. Board Fam. Pract. 2000, 13, 392–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izett-Kay, M.; Barker, K.L.; McNiven, A.; Toye, F. Experiences of urinary tract infection: A systematic review and meta-ethnography. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2022, 41, 724–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikahelmo, R.; Siitonen, A.; Heiskanen, T.; Karkkainen, U.; Kuosmanen, P.; Lipponen, P.; Mäkelä, P.H. Recurrence of Urinary Tract Infection in a Primary Care Setting: Analysis of a I-Year Follow-up of 179 Women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 1996, 22, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Urinary Tract Infection (Recurrent): Antimicrobial Prescribing. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng112/evidence/evidence-review-pdf-6545656621 (accessed on 23 July 2020).

- Foxman, B. Recurring urinary tract infection: Incidence and risk factors. Am. J. Public Health 1990, 80, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Shared decision making. [Internet]. NICE Guideline 197. 2021. Available online: http://www.nice.org.uk/ng197 (accessed on 25 March 2022).

- Elwyn, G.; Frosch, D.; Thomson, R.; Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Kinnersley, P.; Cording, E.; Tomson, D.; Dodd, C.; Rollnick, S.; et al. Shared decision making: A model for clinical practice. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2012, 27, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Williams, N.; Edwards, A.; Elwyn, G. Power imbalance prevents shared decision making. BMJ 2014, 348, g3178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Williams, N.; Lloyd, A.; Edwards, A.; Stobbart, L.; Tomson, D.; Macphail, S.; Dodd, C.; Brain, K.; Elwyn, G.; Thomson, R. Implementing shared decision making in the NHS: Lessons from the MAGIC programme. BMJ 2017, 357, j1744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph-Williams, N.; Williams, D.; Wood, F.; Lloyd, A.; Brain, K.; Thomas, N.; Prichard, A.; Goodland, A.; McGarrigle, H.; Sweetland, H.; et al. A descriptive model of shared decision making derived from routine implementation in clinical practice (‘Implement-SDM’): Qualitative study. Patient Educ. Couns. 2019, 102, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elwyn, G.; Durand, M.A.; Song, J.; Aarts, J.; Barr, P.J.; Berger, Z.; Cochran, N.; Frosch, D.; Galasiński, D.; Gulbrandsen, P.; et al. A three-talk model for shared decision making: Multistage consultation process. BMJ 2017, 359, j4891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noyes, J.; Booth, A.; Cargo, M.; Flemming, K.; Harden, A.; Harris, J.; Garside, R.; Hannes, K.; Pantoja, T.; Thomas, J. Chapter 21: Qualitative evidence [Internet]. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2 (Updated February 2021); Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Cochrane: London, UK, 2021; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 19 January 2022).

- Noblit, G.; Hare, R. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins, S.; Lewin, S.; Smith, H.; Engel, M.; Fretheim, A.; Volmink, J. Conducting a meta-ethnography of qualitative literature: Lessons learnt. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2008, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Britten, N.; Campbell, R.; Pope, C.; Donovan, J.; Morgan, M.; Pill, R. Using meta ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: A worked example. J. Health Serv. Res. Policy 2002, 7, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- France, E.F.; Cunningham, M.; Ring, N.; Uny, I.; Duncan, E.A.S.; Jepson, R.G.; Maxwell, M.; Roberts, R.J.; Turley, R.L.; Booth, A.; et al. Improving reporting of meta-ethnography: The eMERGe reporting guidance. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2019, 19, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flower, A.; Winters, D.; Bishop, F.L.; Lewith, G. The challenges of treating women with recurrent urinary tract infections in primary care: A qualitative study of GPs’ experiences of conventional management and their attitudes towards possible herbal options. Prim. Health Care Res. Dev. 2015, 16, 597–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pat, J.J.; Aart T vd Steffens, M.G.; Witte, L.P.W.; Blanker, M.H. Assessment and treatment of recurrent urinary tract infections in women: Development of a questionnaire based on a qualitative study of patient expectations in secondary care. BMC Urol. 2020, 20, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, V.C.S.; Thum, L.W.; Sadun, T.; Markowitz, M.; Maliski, S.L.; Ackerman, A.L.; Anger, J.; Kim, J.-H. Fear and Frustration among Women with Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections: Findings from Patient Focus Groups. J. Urol. 2021, 206, 688–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, A. “Brimful of STARLITE”: Toward standards for reporting literature searches. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2006, 94, 421–429.e205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Qualitative Checklist [Internet]. 2018. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Campbell, R.; Pound, P.; Pope, C.; Britten, N.; Pill, R.; Morgan, M.; Donovan, J. Evaluating meta-ethnography: A synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care. Soc. Sci. Med. 2003, 56, 671–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lewin, S.; Booth, A.; Glenton, C.; Munthe-Kaas, H.; Rashidian, A.; Wainwright, M.; Bohren, M.A.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Colvin, C.J.; Garside, R.; et al. Applying GRADE-CERQual to qualitative evidence synthesis findings: Introduction to the series. Implement. Sci. 2018, 13 (Suppl. 1), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GRADE-CERQual Interactive Summary of Qualitative Findings (iSoQ) [Computer program], Version 1.0; Norwegian Institute of Public Health (developed by the Epistemonikos Foundation, Megan Wainwright Consulting and the Norwegian Institute of Public Health for the GRADE-CERQual Project Group): Oslo, Norway, 2022. Available online: https://isoq.epistemonikos.org (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Gonzalez, G.; Vaculik, K.; Khalil, C.; Zektser, Y.; Arnold, C.; Almario, C.V.; Spiegel, B.; Anger, J. Using Large-scale Social Media Analytics to Understand Patient Perspectives about Urinary Tract Infections: Thematic Analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2022, 24, e26781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croghan, S.M.; Khan, J.S.A.; Jacob, P.T.; Flood, H.D.; Giri, S.K. The recurrent urinary tract infection health and functional impact questionnaire (RUHFI-Q): Design and feasibililty assessment of a new evaluation scale. Can. J. Urol. 2021, 28, 10729–10732. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, I.; Olofsson, B.; Gustafson, Y.; Fagerström, L. Older women’s experiences of suffering from urinary tract infections. J. Clin. Nurs. 2014, 23, 1385–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigoryan, L.; Mulgirigama, A.; Powell, M.; Schmiemann, G. The emotional impact of urinary tract infections in women: A qualitative analysis. BMC Womens Health 2022, 22, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groen, S.; Lagro-Janssen, A.L.M. The course of recurrent urinary tract infections in non-pregnant women of childbearing age, the consequences for daily life and the ideas of the patients. Ned. Tijdschr. Geneeskd. 2005, 149, 1048–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Gulliford, M.C.; Charlton, J.; Boiko, O.; Winter, J.R.; Rezel-Potts, E.; Sun, X.; Burgess, C.; McDermott, L.; Bunce, C.; Shearer, J.; et al. Safety of reducing antibiotic prescribing in primary care: A mixed-methods study. Health Serv. Deliv. Res. 2021, 9, 34014625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcombe, J. Urinary Tract Infection in Women Aged 18–64: Doctors’, Patients’, and Lay Perceptions and Understandings. Ph.D. Thesis, Durham University, Durham, UK, 2012. Available online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/3572/ (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Cooper, E.; Jones, L.; Joseph, A.; Allison, R.; Gold, N.; Larcombe, J.; Moore, P.; McNulty, C. Diagnosis and management of uti in primary care settings—A qualitative study to inform a diagnostic quick reference tool for women under 65 years. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Antimicrobial Stewardship: Quality Standard [QS121] [Internet]. 2016. Available online: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/qs121/chapter/quality-statement-2-back-up-delayed-prescribing (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Toye, F.; Barker, K.L. A meta-ethnography to understand the experience of living with urinary incontinence: “Is it just part and parcel of life?”. BMC Urol. 2020, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullough, A.R.; Parekh, S.; Rathbone, J.; del Mar, C.B.; Hoffmann, T.C. A systematic review of the public’s knowledge and beliefs about antibiotic resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkman, I.; Berg, J.; Viberg, N.; Stålsby Lundborg, C. Awareness of antibiotic resistance and antibiotic prescribing in UTI treatment: A qualitative study among primary care physicians in Sweden. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2013, 31, 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecky, D.M.; Howdle, J.; Butler, C.C.; McNulty, C.A. Optimising management of UTIs in primary care: A qualitative study of patient and GP perspectives to inform the development of an evidence-based, shared decision-making resource. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 70, e330–e338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane, S.; Domegan, C.; Callan, A.; Galvin, S.; Cormican, M.; Bennett, K.; Murphy, A.; Vellinga, A. Using qualitative insights to change practice: Exploring the culture of antibiotic prescribing and consumption for urinary tract infections. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e008894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisgaard, L.; Andersen, C.A.; Jensen, M.S.A.; Bjerrum, L.; Hansen, M.P. Danish gps’ experiences when managing patients presenting to general practice with symptoms of acute lower respiratory tract infections: A qualitative study. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.J.; Halls, A.V.; Tonkin-Crine, S.; Moore, M.V.; Latter, S.E.; Little, P.; Eyles, C.; Postle, K.; Leydon, G.M. General practitioner and nurse prescriber experiences of prescribing antibiotics for respiratory tract infections in UK primary care out-ofhours services (the UNITE study). J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 795–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, C.C.; Rollnick, S.; Pill, R.; Maggs-Rapport, F.; Stott, N. Understanding the culture of prescribing: Qualitative study of general practitioners’ and patients’ perceptions of antibiotics for sore throats. Br. Med. J. 1998, 317, 637–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duane, S.; Beatty, P.; Murphy, A.W.; Vellinga, A. Exploring experiences of delayed prescribing and symptomatic treatment for urinary tract infections among general practitioners and patients in ambulatory care: A qualitative study. Antibiotics 2016, 5, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flemming, K.; Noyes, J. Qualitative Evidence Synthesis: Where Are We at? Int. J. Qual. Methods 2021, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| STARLITE Category | Description |

|---|---|

| Sampling strategy | Comprehensive. |

| Type of studies | Primary qualitative studies using both qualitative methods for data collection and analysis. |

| Approaches | Electronic databases, reference-list searching, and citation tracking of included studies. |

| Range of years | Primary search—database conception to November 2021. Updated search—November 2021 to June 2022. |

| Limits | No limits. |

| Inclusion and exclusions | Primary care/General Practice or outpatient secondary care. Inclusion criteria: Women aged 18 years and older with rUTI. HCPs managing adult women with rUTI. Primary qualitative studies and mixed methods studies using qualitative methods to collect data and analyse them. Exclusion criteria: Patients requiring intermittent self-catheterisation or long-term catheterisation. Patients who have undergone pelvic or bladder surgery or radiotherapy. Patients with multiple sclerosis or another neurological condition affecting the urinary tract. Pregnant patients. |

| Terms used | MEDLINE search strategy: exp urinary tract infections/ exp cystitis/ exp pyelitis/ (UTI or RUTI or cystitis* or bacteriuria* or pyelonephriti* or pyonephrosi* or pyelocystiti* or pyuri* or urosepsis* or uroseptic*).ti,ab. ((bladder* or genitourin* or genito urin* or kidney* or pyelo* or renal* or ureter* or ureth* or urin* or urolog* or urogen* or urinary tract*) adj3 (infect* or bacteria* or microbial* or sepsis* or nflame*)).ti,ab. 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 Gender Identity/ Sex Characteristics/ Sex Determination/ Sex Distribution/ Sex Factors/ exp Women/ Womens Health/ Womens Health Services/ Health Care for Women International.jn. Journal of The American Medical Womens Association.jn. Women & Health.jn. Womens Health Issues.jn. female*.tw. gender*.tw. girl*.tw. mother*.tw widow*.tw. woman*.tw. women*.tw. or/7–25 ((“semi-structured” or semistructured or unstructured or informal or “in-depth” or indepth or “face-to-face” or structured or guide) adj3 (interview* or discussion* or questionnaire*)).ti,ab. (focus group* or qualitative or ethnograph* or fieldwork or “field work” or “key informant”).ti,ab. interviews as topic/ or focus groups/ or narration/ or qualitative research/ 27 or 28 or 29 6 and 26 and 30 |

| Electronic sources | MEDLINE, Embase, CINAHL, PsycInfo, ASSIA, Web of Science, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Epistemonikos, Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials, OpenGrey, and the Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC). |

| Reference (Ref. no.) and Country | Population/Setting | Method of Data Collection | Method of Data Analysis | Study Participants | CASP Quality Appraisal Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Croghan 2021 [33] Ireland | Women recruited from secondary-care clinics (aged 23–38 years) | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 10 participants | Low |

| Eriksson 2014 [34] Sweden | Women aged 67–96 years from primary care | Semi-structured interviews | Qualitative content analysis | 20 participants | High |

| Flower 2014 [5] U.K. | Postings on a web forum (women who disclosed age were 13–65 years) | “Qualitative description” | Qualitative description | 5386 postings (915 topics) | Moderate |

| Gonzalez 2022 [31] U.S.A. | Online postings (ages not stated) | “Data mining” | Qualitative thematic analysis and a latent Dirichlet allocation | 83,589 online posts by 53,460 users (from 859 websites) | Low |

| Grigoryan 2022 [35] Germany and U.S.A. | Women aged 18 to over 70 years recruited via a patient community panel and physician referrals (50% had experienced rUTI) | Semi-structured interviews with semi-structured narrative self-task component | Thematic synthesis | 65 participants (35 participants with > 2 UTIs in the last year) | Moderate |

| Groen 2005 [36] The Netherlands | Women aged 15–49 (15 were aged over 20 years) from primary care | Semi-structured interviews | Not stated | 21 participants | Low |

| Gulliford 2021 [37] U.K. | Women and men aged 20–99 years attending GP with an infection | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic synthesis | 31 participants (11 with a UTI) | Moderate |

| Larcombe 2012 [38] U.K. | Women aged 18–64 years from primary care (rUTI and non-rUTI) | Focus groups and semi- structured interviews | Grounded theory | 2 focus groups (10 participants) and 12 interviews | High |

| Pat 2020 [23] The Netherlands | Women referred to secondary care (Urology Department) (aged 32–86 years) | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 6 participants | Moderate |

| Scott 2021 [24] U.S.A. | Women aged 20–81 years recruited from “female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery clinics” | Focus groups | Grounded theory | 6 focus groups, 29 participants | Moderate |

| Cooper 2020 [39] U.K. | Primary care staff (ages not stated) | Focus groups | Theoretical domains framework | 8 focus groups, 57 participants | Moderate |

| Flower 2015 [22] U.K. | GPs (aged 34–59 years) | Semi-structured interviews | Thematic analysis | 15 participants | Moderate |

| Larcombe 2012 [38] U.K. | Primary-care staff, including GPs, GPs in training, nurses, pharmacists, administrative staff, and medical managers (ages not stated) | Focus groups and semi-structured interviews | Grounded theory | 12 focus groups (72 participants) and 2 interviews. | High |

| Summarised Review Finding | GRADE-CERQual Assessment of Confidence | Explanation of GRADE-CERQual Assessment | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with Recurrent UTIs | ||||

| 1 | Most women describe a long history of rUTIs, with variability of frequency, severity, symptoms, and ability to self-diagnose. | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, minor concerns regarding adequacy, and minor concerns regarding relevance. | Grigoryan et al., 2022 [35]; Croghan et al., 2021 [33]; Scott et al., 2021 [24]; Eriksson et al., 2014 [34]; Flower et al., 2014 [5]; Larcombe 2012 [38] |

| 2 | Various factors are described as triggers for rUTIs, and patients worry about a serious underlying cause. | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, minor concerns regarding adequacy, and minor concerns regarding relevance. | Grigoryan et al., 2022 [35]; Groen and Lagro-Janssen 2005 [36]; Pat et al., 2020 [23]; Gonzalez et al., 2022 [31]; Flower et al., 2014 [5]; Larcombe 2012 [38] |

| 3 | Recurrent UTIs generally have significant and widespread effects on women’s quality-of-life. | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, minor concerns regarding adequacy, and minor concerns regarding relevance. | Grigoryan et al., 2022 [35]; Groen and Lagro-Janssen 2005 [36]; Croghan et al., 2021 [33]; Pat et al., 2020 [23]; Gonzalez et al., 2022 [31]; Eriksson et al., 2014 [34]; Flower et al., 2014 [5]; Larcombe 2012 [38] |

| 4 | Women with an rUTI commonly use self-help, lifestyle, and Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) options to try to treat and prevent UTIs. | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, minor concerns regarding adequacy, and minor concerns regarding relevance. | Grigoryan et al., 2022 [35]; Groen and Lagro-Janssen 2005 [36]; Pat et al., 2020 [23]; Scott et al., 2021 [24]; Gonzalez et al., 2022 [31]; Eriksson et al., 2014 [34]; Flower et al., 2014 [5]; Larcombe 2012 [38] |

| 5 | The effectiveness of antibiotics varied, and patients are concerned about their use. | Moderate confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, minor concerns regarding adequacy, and minor concerns regarding relevance. | Grigoryan et al., 2022 [35]; Gulliford et al., 2021 [37]; Pat et al., 2020 [23]; Scott et al., 2021 [24]; Gonzalez et al., 2022 [31]; Flower et al., 2014 [5]; Larcombe 2012 [38] |

| 6 | Women with rUTIs seek healthcare for most, but not all, UTIs. They describe anger and frustration with healthcare in terms of their care, the use of antibiotics, and an underestimation of the impact of rUTIs. | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, minor concerns regarding coherence, no/very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and minor concerns regarding relevance. | Grigoryan et al., 2022 [35]; Pat et al., 2020 [23]; Scott et al., 2021 [24]; Gonzalez et al., 2022 [31]; Eriksson et al., 2014 [34]; Flower et al., 2014 [5]; Larcombe 2012 [38] |

| 7 | Women sought information and support from a variety of sources and feel that more information and research are needed. | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, no/very minor concerns regarding adequacy, and minor concerns regarding relevance. | Pat et al., 2020 [23]; Scott et al., 2021 [24]; Gonzalez et al., 2022 [31]; Eriksson et al., 2014 [34]; Flower et al., 2014 [5] |

| Healthcare Professionals | ||||

| 8 | There are differences in the use of, and reason for, conducting a urine culture. | Low confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, serious concerns regarding adequacy, and no/very minor concerns regarding relevance. | Flower et al., 2015 [22]; Cooper et al., 2020 [39]; Larcombe 2012 [38] |

| 9 | Making the correct diagnosis is important, and HCPs worry about missing serious disease. | Low confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, serious concerns regarding adequacy, and no/very minor concerns regarding relevance. | Flower et al., 2015 [22]; Cooper et al., 2020 [39] |

| 10 | HCPs appreciate that rUTIs have a significant impact on quality-of-life. | Low confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, serious concerns regarding adequacy, and no/very minor concerns regarding relevance. | Flower et al., 2015 [22] |

| 11 | HCPs believe self-help measures are important to prevent UTI recurrence. | Low confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, minor concerns regarding coherence, serious concerns regarding adequacy, and no/very minor concerns regarding relevance. | Flower et al., 2015 [22]; Cooper et al., 2020 [39] |

| 12 | Some HCPs are interested in the use of CAMs but have significant concerns about their use and admit a lack of knowledge about them. | Low confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, serious concerns regarding adequacy, and no/very minor concerns regarding relevance. | Flower et al., 2015 [22] |

| 13 | HCPs feel that antibiotics are effective in the short term but are concerned about their use. | Low confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, serious concerns regarding adequacy, and no/very minor concerns regarding relevance. | Flower et al., 2015 [22]; Cooper et al., 2020 [39] |

| 14 | Attitudes toward when to refer to secondary care and its benefits varied amongst HCPs. | Low confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, serious concerns regarding adequacy, and no/very minor concerns regarding relevance. | Cooper et al., 2020 [39]; Larcombe 2012 [38] |

| 15 | HCPs must consider and balance several competing interests when managing rUTIs. | Low confidence | Minor concerns regarding methodological limitations, no/very minor concerns regarding coherence, serious concerns regarding adequacy, and no/very minor concerns regarding relevance. | Flower et al., 2015 [22]; Cooper et al., 2020 [39]; Larcombe 2012 [38] |

| Concepts | 1st- and 2nd-Order Construct Interpretations | 3rd-Order Constructs | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Duration and frequency of rUTIs |

| Most women with an rUTI describe a long history of recurrent UTIs with variability in terms of UTI frequency, severity, presence of typical and atypical symptoms, and ability to self-diagnose recurrence. | 6 |

| Wide-ranging typical and atypical symptoms |

| ||

| Self-diagnosis of UTI recurrence | |||

| Causes and/or triggers of rUTIs |

| Various factors, including lifestyle, hormonal, environmental, and stress are described as potential causes or triggers for rUTIs. There is also fear of an underlying cause and consequence of recurrent UTIs, and women blame themselves for treatment failure and recurrence. | 6 |

| Anxiety and fear of rUTIs |

| ||

| Physical impact |

| Recurrent UTIs generally have a significant and widespread effect on women’s quality-of-life. They impact women physically and psychologically and have significant impacts on their relationships, work, home, and social lives. However, there is variability between women on the impact of rUTIs, from none to severe. | 8 |

| Psychological impact |

| ||

| Impact on relationships |

| ||

| Impact on work/education/home life |

| ||

| Impact on social and leisure activities |

| ||

| Variable impact on quality-of-life |

| ||

| Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) |

| Women with rUTIs commonly use self-help, lifestyle, and CAM options to try to prevent rUTIs with variable success. Self-care can help women feel empowered about managing their rUTI. | 9 |

| Lifestyle-management strategies |

| ||

| Over-the-counter medication/therapies |

| ||

| Empowerment |

| ||

| The effectiveness of antibiotics |

| The effectiveness of antibiotics varies from being effective short term to having minimal or no impact. Attitudes about their use vary, and there is fear and concern about their use. | 7 |

| Concerns and fears about antibiotics |

| ||

| Consulting behaviour |

| Women with rUTIs often seek healthcare for UTI recurrence but describe anger and frustration about their care, the use of antibiotics, and underestimation of the impact of the rUTI. | 7 |

| Positive experiences of healthcare |

| ||

| Negative experiences and frustrations with healthcare |

| ||

| Use of antibiotics by HCPs |

| ||

| Underestimation of the impact of rUTIs by HCPs |

| ||

| Lack of or need for more information on rUTIs |

| There is a need for more information on the causes and treatment options, and this is sought via a variety of sources. | 7 |

| Seeking more information and sources of information |

| ||

| Support networks for women with rUTIs |

| ||

| Need for more research |

|

| Concepts | 1st- and 2nd-Order Construct Interpretations | 3rd-Order Constructs | Number of Studies |

|---|---|---|---|

| The use of urine sampling |

| There are differences in the use of and the reason for conducting urine sampling from making a diagnosis to identifying unusual organisms and resistance. Healthcare professionals (HCPs) also highlight the limitations of urine sampling, including a mismatch with symptoms and potential for “over-medicalisation” [22]. | 3 |

| The benefits and limitations of urine culture |

| ||

| Making the correct diagnosis and not missing serious disease |

| HCPs consider that there are numerous causes for rUTIs, including lifestyle and medical factors. Making the correct diagnosis of rUTIs is important, and HCPs worry about missing serious disease. | 2 |

| Causes and triggers for rUTIs |

| ||

| The impact of rUTIs on patients |

| HCPs appreciate that rUTIs have a significant impact on quality-of-life and affect numerous areas of patients’ lives. The impact on patients also influences the provision of antibiotics. | 1 |

| Influence of the impact on management |

| ||

| Self-care advice given |

| HCPs believe that self-help measures are important to prevent UTI recurrence, including hydration and hygiene advice. HCPs believe that more information is needed to improve self-management. | 2 |

| The use of self-care advice in rUTI |

| ||

| Lifestyle and behavioural changes and over-the-counter and natural remedies |

| ||

| Preventative information for patients |

| ||

| Views on complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) |

| HCPs are interested in the use of CAM and feel that they could be effective. However, they have significant concerns about their safety and regulation, and their lack of knowledge prohibits them from recommending them. | 1 |

| Concerns about CAM |

| ||

| HCPs’ knowledge of CAM |

| ||

| When HCPs would consider CAM use |

| ||

| Effectiveness of antibiotics |

| HCPs feel antibiotics are effective in the short term but have significant concerns about their use, including side-effects, developing resistance, and over-medicalisation. | 2 |

| Concerns about antibiotic use |

| ||

| Discussions with patients about the benefits and risks of antibiotics |

| ||

| Further investigation and referral to secondary care |

| Attitudes towards when refer to secondary care for further investigation and its benefit varies between HCPs. Some refer based on specific criteria, whereas others base it on gut feeling. Some HCPs feel that further investigation has little impact on management. | 2 |

| Over-medicalisation |

| HCPs must consider and balance several competing interests in rUTI treatment. These include a desire to improve patient’s symptoms and minimise antibiotic use due to concerns about resistance and limited, conflicting, or lacking guidance. patient expectation and concerns about “over-medicalising” [22] UTIs. | 3 |

| Lack of or conflicting advice |

| ||

| Desire to improve patient’s symptoms |

| ||

| Risk of resistance |

| ||

| Patient expectation |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sanyaolu, L.N.; Hayes, C.V.; Lecky, D.M.; Ahmed, H.; Cannings-John, R.; Weightman, A.; Edwards, A.; Wood, F. Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Experiences and Views of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis and Meta-Ethnography. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030434

Sanyaolu LN, Hayes CV, Lecky DM, Ahmed H, Cannings-John R, Weightman A, Edwards A, Wood F. Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Experiences and Views of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis and Meta-Ethnography. Antibiotics. 2023; 12(3):434. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030434

Chicago/Turabian StyleSanyaolu, Leigh N., Catherine V. Hayes, Donna M. Lecky, Haroon Ahmed, Rebecca Cannings-John, Alison Weightman, Adrian Edwards, and Fiona Wood. 2023. "Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Experiences and Views of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis and Meta-Ethnography" Antibiotics 12, no. 3: 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030434

APA StyleSanyaolu, L. N., Hayes, C. V., Lecky, D. M., Ahmed, H., Cannings-John, R., Weightman, A., Edwards, A., & Wood, F. (2023). Patients’ and Healthcare Professionals’ Experiences and Views of Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections in Women: Qualitative Evidence Synthesis and Meta-Ethnography. Antibiotics, 12(3), 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics12030434