Impact on Antibiotic Resistance, Therapeutic Success, and Control of Side Effects in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) of Daptomycin: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Structure and Mechanism of Action of Daptomycin

1.2. Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Considerations

2. Results

2.1. Therapeutic Monitoring Methods

2.2. Bacterial Resistance

2.3. Therapeutic Success and Control of Side Effects

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

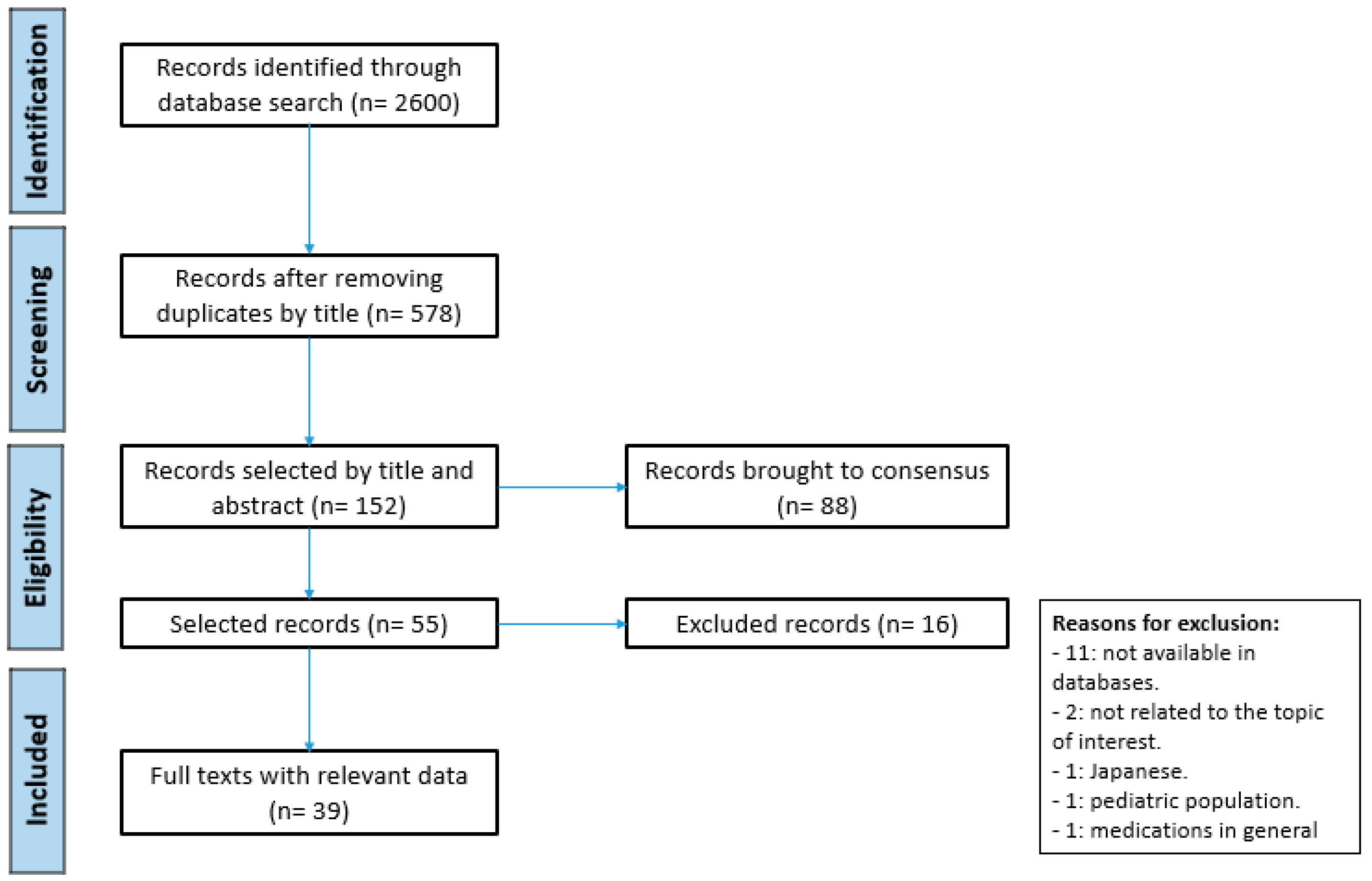

4.1. Search Strategy

4.2. Evaluation and Selection of Studies

4.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

4.4. Graphing the Data

4.5. Collecting, Summarizing, and Reporting the Results

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. WHO Publishes List of Bacteria for Which New Antibiotics Are Urgently Needed. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news/item/27-02-2017-who-publishes-list-of-bacteria-for-which-new-antibiotics-are-urgently-needed (accessed on 13 January 2020).

- World Health Organization. Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/es/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Heidary, M.; Khosravi, A.D.; Khoshnood, S.; Nasiri, M.J.; Soleimani, S.; Goudarzi, M. Daptomycin. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tacconelli, E. Global Priority List of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria to Guide Research, Discovery, and Development of New Antibiotics. Essential Medicines and Health Products; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Antibiotic/Antimicrobial Resistance: Biggest Threats. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/biggest_threats.html (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Abdul-Aziz, M.H.; Alffenaar, J.C.; Bassetti, M.; Bracht, H.; Dimopoulos, G.; Marriott, D.; Neely, M.N.; Paiva, J.A.; Pea, F.; Sjovall, F.; et al. Antimicrobial therapeutic drug monitoring in critically ill adult patients: A Position Paper. Intensive Care Med. 2020, 46, 1127–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jager, N.G.; van Hest, R.M.; Lipman, J.; Taccone, F.S.; Roberts, J.A. Therapeutic drug monitoring of anti-infective agents in critically ill patients. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2016, 9, 961–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polillo, M.; Tascini, C.; Lastella, M.; Malacarne, P.; Ciofi, L.; Viaggi, B.; Bocci, G.; Menichetti, F.; Danesi, R.; Del Tacca, M.; et al. A Rapid High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Method to Measure Linezolid and Daptomycin Concentrations in Human Plasma. Ther. Drug Monit. 2010, 32, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CDC. Biggest Threats and Data. Available online: http://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/threat-report-2013/ (accessed on 15 January 2021).

- Holland, T.L.; Arnold, C.; Fowler, V.G., Jr. Clinical management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: A review. JAMA 2014, 312, 1330–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor, S.D.; Palmer, M. The action mechanism of daptomycin. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016, 24, 6253–6268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debono, M.; Abbott, B.J.; Molloy, R.M.; Fukuda, D.S.; Hunt, A.H.; Daupert, V.M.; Counter, F.T.; Ott, J.L.; Carrell, C.B.; Howard, L.C.; et al. Enzymatic and chemical modifications of lipopeptide antibiotic A21978C: The synthesis and evaluation of daptomycin (LY146032). J. Antibiot. 1988, 41, 1093–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micklefield, J. Daptomycin structure and mechanism of action revealed. Chem. Biol. 2004, 11, 887–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, S.W.; Jung, D.; Calhoun, J.R.; Lear, J.D.; Okon, M.; Scott, W.R.; Hancock, R.E.; Straus, S.K. Effect of divalent cations on the structure of the antibiotic daptomycin. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008, 37, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Lerma, F.; Gracia-Arnillas, M.P. Daptomicina para el tratamiento de las infecciones por microorganismos grampositivos en el paciente crítico. Med. Clín. 2010, 135, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Zhang, C.; Di, Y.; Li, N.; Yao, H.; Dong, Y. An LC-MS/MS method for quantification of daptomycin in dried blood spot: Application to a pharmacokinetics study in critically ill patients. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2018, 41, 786–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cojutti, P.G.; Candoni, A.; Ramos-Martin, V.; Lazzarotto, D.; Zannier, M.E.; Fanin, R.; Hope, W.; Pea, F. Population pharmacokinetics and dosing considerations for the use of daptomycin in adult patients with haematological malignancies. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 2342–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galar, A.; Munoz, P.; Valerio, M.; Cercenado, E.; Garcia-Gonzalez, X.; Burillo, A.; Sanchez-Somolinos, M.; Juarez, M.; Verde, E.; Bouza, E. Current use of daptomycin and systematic therapeutic drug monitoring: Clinical experience in a tertiary care institution. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 53, 40–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcone, M.; Russo, A.; Cassetta, M.I.; Lappa, A.; Tritapepe, L.; d’Ettorre, G.; Fallani, S.; Novelli, A.; Venditti, M. Variability of pharmacokinetic parameters in patients receiving different dosages of daptomycin: Is therapeutic drug monitoring necessary? J. Infect. Chemother. 2013, 19, 732–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyadera, Y.; Naito, T.; Yamada, T.; Kawakami, J. Simple LC-MS/MS Methods Using Core–Shell Octadecylsilyl Microparticulate for the Quantitation of Total and Free Daptomycin in Human Plasma. Ther. Drug Monit. 2018, 40, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avent, M.L.; Rogers, B.A. Optimising antimicrobial therapy through the use of Bayesian dosing programs. Int. J. Clin. Pharm. 2019, 41, 1121–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobin, C.M.; Darville, J.M.; Lovering, A.M.; Macgowan, A.P. An HPLC assay for daptomycin in serum. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2008, 62, 1462–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, J.A.; Norris, R.; Paterson, D.L.; Martin, J.H. Therapeutic drug monitoring of antimicrobials. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 73, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decosterd, L.A.; Widmer, N.; André, P.; Aouri, M.; Buclin, T. The emerging role of multiplex tandem mass spectrometry analysis for therapeutic drug monitoring and personalized medicine. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2016, 84, 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodamer, M.; Jacob, V.; Strauss, R.; Ganslmayer, M.; Gleich, C.; Sörgel, F.; Kinzig, M. New horizons to modern therapeutic drug monitoring−use of tandem mass spectrometry to analyze the 40 most important anti-infectives. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2009, 15, 1651. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland, J.; Bowker, K.; Noel, A.; Elliot, H.; Money, P.; Lovering, A. Therapeutic drug monitoring of daptomycin: A 4-year audit of levels from a UK clinical antibiotic service. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2012, 18, 1624. [Google Scholar]

- Cojutti, P.G.; Carnelutti, A.; Mattelig, S.; Sartor, A.; Pea, F. Real-Time Therapeutic Drug Monitoring-Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic Optimization of Complex Antimicrobial Therapy in a Critically Ill Morbidly Obese Patient. Grand Round/A Case Study. Ther. Drug Monit. 2020, 42, 349–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pea, F.; Cojutti, P.; Sbrojavacca, R.; Cadeo, B.; Cristini, F.; Bulfoni, A.; Furlanut, M. TDM-guided therapy with daptomycin and meropenem in a morbidly obese, critically ill patient. Ann. Pharmacother. 2013, 45, e37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taegtmeyer, A.B.; Kononowa, N.; Fasel, D.; Haschke, M.; Burkhalter, F. Successful Treatment of a Pacemaker Infection with Intraperitoneal Daptomycin. Perit. Dial. Int. 2016, 36, 114–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tascini, C.; Tagliaferri, E.; DI Lonardo, A.; Lambelet, P.; DI Paolo, A.; Menichetti, F. Daptomycin blood concentrations and clinical failure: Case report. J. Chemother. 2011, 23, 238–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baietto, L.; D’Avolio, A.; De Rosa, F.G.; Garazzino, S.; Michelazzo, M.; Ventimiglia, G.; Siccardi, M.; Simiele, M.; Sciandra, M.; Di Perri, G. Development and validation of a simultaneous extraction procedure for HPLC-MS quantification of daptomycin, amikacin, gentamicin, and rifampicin in human plasma. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 396, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baietto, L.; D’Avolio, A.; Pace, S.; Simiele, M.; Marra, C.; Ariaudo, A.; Di Perri, G.; De Rosa, F.G. Development and validation of an UPLC-PDA method to quantify daptomycin in human plasma and in dried plasma spots. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2014, 88, 66–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decosterd, L.A.; Mercier, T.; Ternon, B.; Cruchon, S.; Guignard, N.; Lahrichi, S.; Pesse, B.; Rochat, B.; Burger, R.; Lamoth, F.; et al. Validation and clinical application of a multiplex high performance liquid chromatography—tandem mass spectrometry assay for the monitoring of plasma concentrations of 12 antibiotics in patients with severe bacterial infections. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2020, 1157, 122160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gika, H.G.; Michopoulos, F.; Divanis, D.; Metalidis, S.; Nikolaidis, P.; Theodoridis, G.A. Daptomycin determination by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry in peritoneal fluid, blood plasma, and urine of clinical patients receiving peritoneal dialysis treatment. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2010, 397, 2191–2197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregoire, M.; Leroy, A.G.; Bouquie, R.; Malandain, D.; Dailly, E.; Boutoille, D.; Renaud, C.; Jolliet, P.; Caillon, J.; Deslandes, G. Simultaneous determination of ceftaroline, daptomycin, linezolid and rifampicin concentrations in human plasma by on-line solid phase extraction coupled to high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2016, 118, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosl, J.; Gessner, A.; El-Najjar, N. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for the quantification of moxifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, daptomycin, caspofungin, and isavuconazole in human plasma. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2018, 157, 92–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdil, J.F.; Tonini, J.; Stanke-Labesque, F. Simultaneous quantitation of azole antifungals, antibiotics, imatinib, and raltegravir in human plasma by two-dimensional high-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. B Anal. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2013, 919–920, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luci, G.; Cucchiara, F.; Ciofi, L.; Lastella, M.; Danesi, R.; Di Paolo, A. A new validated HPLC-UV method for therapeutic monitoring of daptomycin in comparison with reference mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2020, 182, 113132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogami, C.; Tsuji, Y.; Kasai, H.; Hiraki, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Matsunaga, K.; Karube, Y.; To, H. Evaluation of pharmacokinetics and the stability of daptomycin in serum at various temperatures. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2017, 57, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Reiber, C.; Senn, O.; Müller, D.; Kullak-Ublick, G.A.; Corti, N. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring of Daptomycin: A Retrospective Monocentric Analysis. Ther. Drug Monit. 2015, 37, 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, R.; Suzuki, Y.; Goto, K.; Yasuda, N.; Koga, H.; Kai, S.; Ohchi, Y.; Sato, Y.; Kitano, T.; Itoh, H. Development and validation of sensitive and selective quantification of total and free daptomycin in human plasma using ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 165, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, I.L.; Sun, H.Y.; Chen, G.Y.; Lin, S.W.; Kuo, C.H. Simultaneous quantification of antimicrobial agents for multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in human plasma by ultra-high-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Talanta 2013, 116, 593–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urakami, T.; Hamada, Y.; Oka, Y.; Okinaka, T.; Yamakuchi, H.; Magarifuchi, H.; Aoki, Y. Clinical pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic analysis of daptomycin and the necessity of high-dose regimen in Japanese adult patients. J. Infect. Chemother. 2019, 25, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdier, M.C.; Bentue-Ferrer, D.; Tribut, O.; Collet, N.; Revest, M.; Bellissant, E. Determination of daptomycin in human plasma by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clinical application. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2011, 49, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenisch, J.M.; Meyer, B.; Fuhrmann, V.; Saria, K.; Zuba, C.; Dittrich, P.; Thalhammer, F. Multiple-dose pharmacokinetics of daptomycin during continuous venovenous haemodiafiltration. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 977–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butterfield, J.M.; Mueller, B.A.; Patel, N.; Cardone, K.E.; Grabe, D.W.; Salama, N.N.; Lodise, T.P. Daptomycin pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in a pooled sample of patients receiving thrice-weekly hemodialysis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 864–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandolpho Tótoli, E.; Garg, S.; Salgado, H.R. Daptomycin: Physicochemical, Analytical, and Pharmacological Properties. Ther. Drug Monit. 2015, 37, 699–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, G.; Sime, F.B.; Lipman, J.; Roberts, J.A. How do we use therapeutic drug monitoring to improve outcomes from severe infections in critically ill patients? BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, M.; Nishioka, H.; Nakasako, S.; Kuramoto, E.; Ikemura, M.; Kamei, H.; Sono, Y.; Sugioka, N.; Fukushima, S.; Hashida, T. Observational retrospective single-centre study in Japan to assess the clinical significance of serum daptomycin levels in creatinine phosphokinase elevation. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 2020, 45, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, T.T.; Palmer, H.R.; Weston, J.; Hirsch, E.B.; Shah, D.N.; Cottreau, J.; Tam, V.H.; Garey, K.W. Evaluation of a daptomycin dose-optimization protocol. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2012, 69, 979–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critchley, I.A.; Draghi, D.C.; Sahm, D.F.; Thornsberry, C.; Jones, M.E.; Karlowsky, J.A. Activity of daptomycin against susceptible and multidrug-resistant Gram-positive pathogens collected in the SECURE study (Europe) during 2000–2001. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 51, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lozano, C.; Torres, C. Actualización en la resistencia antibiótica en Gram positivos. Enferm. Infecc. Microbiol. Clín. 2017, 35, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaman, R.; Jubeh, B.; Breijyeh, Z. Resistance of Gram-Positive Bacteria to Current Antibacterial Agents and Overcoming Approaches. Molecules 2020, 25, 2888. [Google Scholar]

- Sakoulas, G.; Moise, P.A.; Casapao, A.M.; Nonejuie, P.; Olson, J.; Okumura, C.Y.; Rybak, M.J.; Kullar, R.; Dhand, A.; Rose, W.E.; et al. Antimicrobial salvage therapy for persistent staphylococcal bacteremia using daptomycin plus ceftaroline. Clin. Ther. 2014, 36, 1317–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemian, S.M.R.; Farhadi, T.; Ganjparvar, M. Linezolid: A review of its properties, function, and use in critical care. Drug Des. Dev. Ther. 2018, 12, 1759–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rybak, M.J.; Le, J.; Lodise, T.P.; Levine, D.P.; Bradley, J.S.; Liu, C.; Mueller, B.A.; Pai, M.P.; Wong-Beringer, A.; Rotschafer, J.C.; et al. Therapeutic monitoring of vancomycin for serious methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections: A revised consensus guideline and review by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, and the Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists. Am. J. Health Syst. Pharm. 2020, 77, 835–864. [Google Scholar]

- Miró, J.M.; Entenza, J.M.; Del Río, A.; Velasco, M.; Castañeda, X.; Garcia de la Mària, C.; Giddey, M.; Armero, Y.; Pericàs, J.M.; Cervera, C.; et al. High-dose daptomycin plus fosfomycin is safe and effective in treating methicillin-susceptible and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus endocarditis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2012, 56, 4511–4515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grégoire, N.; Marchand, S.; Ferrandière, M.; Lasocki, S.; Seguin, P.; Vourc′h, M.; Barbaz, M.; Gaillard, T.; Launey, Y.; Asehnoune, K.; et al. Population pharmacokinetics of daptomycin in critically ill patients with various degrees of renal impairment. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2019, 74, 117–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhavnani, S.M.; Rubino, C.M.; Ambrose, P.G.; Drusano, G.L. Daptomycin exposure and the probability of elevations in the creatine phosphokinase level: Data from a randomized trial of patients with bacteremia and endocarditis. Clin. Infect. Dis. Off. Publ. Infect. Dis. Soc. Am. 2010, 50, 1568–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2015 Edition/Supplement; The Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide, Austrlia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

| Monitoring Method | Population | Objective | Type of Study | Results | Conclusions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS | Population n = 6, critically ill patients | Develop of a method for the quantification and analysis of daptomycin in a dry blood stain (DBS). | Bioanalytical methodology | RT: Daptomycin: 4.57 min -Average recovery of daptomycin extraction by DBS: 82.48–97.72% -V1/2: 11.56 ± 3.31 h -Cmax: 109.15 ± 56.39 mg/L -Vd: 87.65 ± 42.66 mL/kg -CL: 9.05 ± 5.79 mL/h/kg -AUC24h: 786.93 ± 451.65 | Allows non-invasive sampling, micro-volume blood sample, useful for PK study in critically ill patients. | [16] |

| Population n = 8, human plasma samples | Develop an LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of 3 antibiotics. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Running time: 5.5 min -Accuracy: 95.9–116.6% -Cmin: 3.125 mg/L for daptomycin -Determined Conc.: 40 and 105 mg/L | TDM is useful in intensive care units and other pharmacokinetic studies. | [36] | |

| Population -Age: 54 years -Weight: 94 kg -Backg: hemodialysis (HD) without residual kidney function -Patho: sepsis after insertion of a pacemaker | Describe a case that required administration of daptomycin at the intraperitoneal level due to bacteremia by Gram-positive bacteria. Modify dose guided by TDM. | Case report | -TDM was performed: before, 4 h after, and 24 h after the 1st dose -Cmax: 4 h -At 24 h: daptomycin CL from intraperitoneal dialysis was determined -Daptomycin: 5.3 mg/kg every 48 h reached Cmax -The dose was reduced to 4.3 mg/kg every 48 h and then to 3.2 mg/kg every 48 h -The target Cmin and Cmax were reached on day 22 -The dose was maintained at 300 mg (3.2 mg/kg) intraperitoneally every 48 h until day 32 | The use of intraperitoneal daptomycin may be a possible therapeutic option when there is vascular deficit. TDM can help with serum concentration measurement and dose adjustments to maintain non-toxic concentration. | [29] | |

| N/A | Describe basic TDM concepts, clinical application examples, and the benefit of LC-MS/MS techniques. | Review article | -Measurement of drugs in blood should not replace monitoring with clinical or biological biomarkers -TDM is intended to allow dose adjustment to improve efficacy and prevent toxicity | TDM can contribute to the optimization and individualization of multiple drug dosing. | [24] | |

| Population n = 86 patients divided into 4 groups: 1. CrCl > 30 mL/min 2. CrCl ≤ 30 mL/min without RRT 3. End-stage kidney disease with intermittent hemodialysis 4. Renal failure with continuous RRT | Describe the variability in daptomycin exposure as a routine treatment in a clinical environment. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Cmin was between 2 and 68 mg/L (median, 16.7 mg/L) -Cmax, between 20 and 236 mg/L (median, 66.2 mg/L) -Concentrations were frequently detected in patients with E. faecium and Staphylococcus coagulase (−). -Only 37 patients received daptomycin monotherapy -Average dose: 6 mg/kg -~40 patients received high doses: 6–13.8 mg/kg | Plasma concentration of daptomycin is often unpredictable, given by highly variable drug exposure that is only explained by the administered dose and renal function. | [40] | |

| Population n = 19, patients with peritoneal dialysis | Develop a method for the determination of daptomycin in peritoneal fluid, blood plasma, and urine. | Bioanalytical methodology | Concentration ranges: -Peritoneal fluid: 0.66 to 246 µg of mL -Plasma: 0.55 to 82.23 µg/mL -Urine: 5.2 to 23.68 g/mL | Economic, simple, rapid, and sensitive method. Method useful for monitoring and its application in pharmacokinetic studies. | [34] | |

| Population n = 1 patient, 3 plasma samples | Develop a bioanalytical method (LC-MS/MS) for the quantification of daptomycin plasma concentration in patients with severe infection. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Cmax (30 min): 39 mg/L (>80 mg/L healthy patient) -Cmin (24 h): 14 mg/L (9 mg/L healthy patient) -Dose increased due to persistent bacteremia to 12 mg/kg -Cmax (30 min): 54 mg/L (>80 mg/L healthy patient) -No evidence of side effects | Good alternative to previously proposed HPLC-UV or LC-MS methods. Well suited to analysis time, range of measured concentration, precision, and accuracy. | [44] | |

| Population n = 30 patients | The modern LC-MS/MS has opened a new era for measuring antibiotic levels in blood or tissues in the hospital. | Poster | -It was possible to report the concentration of medications in less than 24 h -It has been used so far in 30 patients in whom the doctor considered vital the monitoring of the concentration of the drug | The use of bioanalytical methods to perform TDM still requires many studies. The impact on mortality cannot be assessed. | [25] | |

| HPLC | Population n = 63, hospitalized patients receiving daptomycin | Assess the dose of daptomycin in a real-life study, variability between patients and clinical impact. | Observational prospective study | -Great inter-individual variability; Cmin: 10.6 mg/L (1.3–44.7 mg/L); Cmax: 44.0 mg/L (3.0–93.7 mg/L) -Adequate dose: 10 mg/kg for endocarditis | Daptomycin TDM optimizes management and prevents toxicity. | [18] |

| Population n = 3 plasma samples Temperature T = −80 °C, −20 °C and 4 °C | Evaluate stability of daptomycin in blood at different temperatures. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Loss of concentration of daptomycin in plasma <10% after 6 months at T: −80 °C and −20 °C -Concentration of daptomycin at 4 °C, decreased more than 70% over 6 months -Concentration of daptomycin at body T (35 °C, 37 °C and 39 °C) decreased >50% after 24 h | Perform level measurement immediately. Daptomycin levels in plasma are stable at T < 20 °C. | [39] | |

| Population n = 35 patients hospitalized | Determine the pharmacokinetic profile of daptomycin. | Non-randomized clinical study | -No patient presented increased CPK -Vd: 0.5 L/kg -Renal function is the main cause of changes in daptomycin clearance V1/2: 9 h AUC/MIC: 692 ± 210 (6 mg/kg/day) 903 ± 280 (8 mg/kg/day) | TDM is needed secondary to a variation of PK/PD of daptomycin in hospitalized patients. | [19] | |

| Population n = 760 plasma samples from 168 patients from 50 hospitals | Provide a TDM service for daptomycin in the UK for 4 years. | Poster | -During 4 years (2007–2011) we received 760 serums samples for daptomycin TDM | ~40% of the samples presented plasma concentration outside the range. -low concentration were more common in patients <18 years. -high concentration were similar in all ages. It is important to perform TDM in patients with daptomycin to optimize treatment. | [26] | |

| Population n = 9 patients Backg: requiring continuous veno-venous hemodiafiltration (CVVHDF) | Determine the pharmacokinetics of daptomycin at a dose of 6 mg/kg and the profiles of conc./t after multiple doses. Compare with current literature to develop robust recommendations regarding daptomycin dosage. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Daptomycin 8 mg kg every 48 h resulted in adequate levels without accumulation -Accumulation: when administered every 24 h -Clearance: 6.1 ± 4.9 mL/min -t1/2: 17.8 ± 9.7 h Cmax: day 1: 62.2 ± 16.2 mg/L day 2: 66.1 ± 17.3 mg/L day 3: 78.5 ± 22.1 mg/L Cmin: >4 mg/L (relevant bacteria were susceptible to daptomycin) | For critically ill patients, a daptomycin dose of 8 mg/kg is recommended, and TDM should be performed if possible. | [45] | |

| Population -Daptomycin: n = 5 patients -Linezolid: n = 14 patients Dose -Daptomycin: 6–8 mg/kg in 30 min -Linezolid: 600 mg every 12 h | Create and validate a sensitive, specific and reliable HPLC method to monitor plasma concentration of daptomycin in patients affected by severe infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria. | Bioanalytical methodology | Retention times: -Daptomycin: 17.4 ± 0.20 min -Accuracy values < 20% -Cmax: 52.8–84.7 mg/L -Cmin: 12.5 ± 3.1 mg/L (associated with reduced risk of increased CPK) -Cmax/MIC: 106–169 | Robust and reliable method. Useful to measure concentration plasma daptomycin and linezolid. | [8] | |

| N/A | Develop an HPLC method to measure plasma concentration in patients with multiorgan failure. | Letter to the Editor | -Daptomycin retention time: ~5 min -Daptomycin: stable after three cycles; 99.1% for the 5 mg/L sample, 102.1% for the 20 mg/L sample and 98.4% for the 100 mg/L sample | Daptomycin stable after freeze/thaw cycles. Ideal method for laboratories requiring a fast response time of the test. | [22] | |

| TDM | Population Age: 59 years Patho: bacteremia due to MRSA secondary to CVC | Present a case of a patient with bacteremia due to MRSA secondary to CVC, with suboptimal doses of daptomycin. | Case report | -Cmax: 12.2 mg/L (recommended level: 98.6 ± 12 mg/L) -Cmin: 2.5 mg/L (recommended level: 9.4 ± 2.5 mg/L) -A dose was given below the recommended: 3.28 mg/kg (recommended dose: 6 mg/kg) | TDM is essential for treatment optimization. TDM prevents the development of side effects, therapeutic failure, and the appearance of bacterial resistance. | [30] |

| N/A | Describe the analytical methods used for the analysis of daptomycin. | Review article | -There are few studies demonstrating analytical methods for the measurement of daptomycin -Most of the studies described are HPLC and UHPLC | TDM is important for special populations More research is required to contribute to a better understanding of this problem and improve the therapeutic response. | [47] | |

| N/A | Review available evidence in relation to TDM of antibiotics. Describe how TDM can be used to positively improve outcomes for critically ill patients. | Review article | -Information on TDM with daptomycin is limited -High protein binding and variable renal clearance make it a candidate for TDM to achieve PK/PD target -It can help reduce the risk of rhabdomyolysis associated with levels of Cmin > 24.3 mg/L, and when using doses higher than recommended | Critically ill patients with sepsis, skin burns, hypoalbuminemia, and requiring RRT would benefit from TDM. TDM works as a mechanism to reduce side effects and optimize doses. | [48] | |

| Population Age: 63 years Backg: morbid obesity and CKD Patho: cellulitis | Describe a case of severe cellulitis, treated with high doses of daptomycin. The dose of daptomycin was optimized by TDM. | Case report | Dose adjustment by TDM: -Daptomycin: 1200 mg/48 h for 30 min→1200 mg/36 h for 30 min -Meropenem: 0.25 mg every 8 h for 6 h→500 mg every 4 h CI -Favorable clinical response at 72 h -Increased CPK for which it was thought to suspend daptomycin | TDM in infected patients can help optimize doses for therapeutic success. | [28] | |

| N/A | Define role of TDM in antibiotic dosing. | Review article | -There are no controlled clinical trials that demonstrate a reduction in mortality from the use of TDM -There are publications that suggest that the use of TDM is probably beneficial to patients | TDM serves as a method to adjust the dose of some particular antibiotics in the relevant population. | [23] | |

| UHPLC-MS/MS | Population n = 2 patients | Develop and validate quantitative method to measure total and free daptomycin in human plasma using UHPLC-MS/MS. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Retention time: 2.17 min -The concentration range of the calibration curve is 0.5 to 200 g/mL, wider than in all previous reports -Cmax and Cmin were reached -Binding to plasma proteins: 97.5–97.9% | Appropriate method for quantifying total concentration plasma and concentration of free daptomycin. Calibration curves with wide ranges capable of measuring Cmax and Cmin. Short measurement and analysis time, accuracy, selectivity, stability, and recovery rate. | [41] |

| Population n = 6, plasma from humans | Provide a simple, fast, and accurate quantification of the concentration of 4 antibiotics. | Bioanalytical methodology | -AUC/MIC daptomycin: 75 and 537 for efficiency -Cmax/MIC: 12 and 94 according to bacterial species -Main marker of skeletal muscle toxicity: CPK elevation (relation with Cmin > 24.3 mg/L) | Method is a good option for prospective PK studies and simultaneous monitoring of anti-MRSA drugs. | [35] | |

| Population n = 6 human plasma samples | Develop a rapid LC-MS/MS method for the simultaneous quantification of 5 antibiotics. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Extraction recovery time: 79.3% to 105.9% -Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation: 1.95–12.77%, 2.56–8.16%, and 2.12–11.38% for low, medium, and high levels | Fast and robust method. Useful for routine TDM and optimization of resource use. | [37] | |

| Population n = 6 blood samples | Develop a bioanalytical method to determine concentration of daptomycin at the plasma level. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Concentration of daptomycin in patient No. 3: 6.8 µg/mL -Accuracy in concentration low, medium, and high of the eight target peaks was: 89.3–110.7% -LOD were <70 ng/mL | Sensitive and selective method. Analysis time: 10 min. Method indicated for the realization of TDM. | [42] | |

| HPLC-UV | Population n = 10 plasma samples | To develop and validate a new chromatography method for the measurement of plasma concentration of daptomycin. Compare method with commercially available LC-MS/MS. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Daptomycin: Cmax: 5.8 min after injection -Inter and intraday coefficients of variability < 15% -Comparison with a commercially available reference LC-MS/MS method showed an excellent correlation (r2 = 0.9474) | -Precise and reproducible method. Quantifies plasma concentration of daptomycin within the min–max range of values expected after drug administration at prescribed dose. | [38] |

| Population n = 30, hemato-oncological adult patients | Evaluate if adequate exposure and pharmacodynamic objectives are achieved in a cohort of hemato-oncological patients with conventional dose. | Observational prospective study | -Dose 6 mg/kg/day: optimal PTA (probability of reaching objective) ≥ 80%, if pathogens with MIC up to 0.25 mg/L -Higher doses: up to 12 mg/kg/day needed to achieve goal if pathogens with MIC 0.5 mg/L in all other scenarios -CL: 0.56 L/h in bone and joint infections; 1.81 L/h in sepsis and bacteremia due to S. aureus | Considering daptomycin doses ≥ 8 mg/kg/day in various onco-hematological patients. | [17] | |

| HPLC-UV and LC-MS/MS | Population Studies in critically ill adult patients | Review available antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral TDM data. Recommend how to use. | Review article | -AUC/MIC >666 for efficiency -Cmin: ≥24.3 mg/L is associated with a greater probability of elevated CPK | Performing TDM is the only safe and effective way to ensure that critically ill patients achieve adequate therapeutic levels. Controlled studies focused on clinical outcomes are needed to justify routine use of TDM. | [6] |

| Population -Critically ill patients | Review the available evidence for anti-infective TDM. Describe its use to optimize the treatment of critically ill patients. | Review article | -Bactericidal activity of daptomycin: AUC0–24/MIC: 38–442, > AUC0–24/MIC efficacy > 666 -In vitro: AUC0–24/MIC ≥ 200 resistance suppression -Cmax/MIC: 12–94 optimal bacteriostatic effect -Cmin > 24.3 mg/L (probability of CPK elevation) | TDM could be useful to optimize treatment in critically ill patients. | [7] | |

| UHPLC-PDA | Population n = 46 patients, 52 cases (6 patients received multiple courses of treatment) | Assess the clinical importance of Cmin in relation to the safety of daptomycin use. | Observational retrospective study | -Cmin > 24.3 mg/mL in 7 cases (none had elevated CPK) -CPK elevation: 2 patients (none needed treatment interruption) -Treatment interruption: 4 patients, suspected adverse effects; Cmin: 8.6 and 8.1 mg/L -2 patients: doses 9.4 and 10.0 mg/kg; Cmin equal to dose < 9 mg/kg | Daptomycin is safe The level of Cmin of 24.3 mg/L is not considered clinically significant for the elevation of CPK, adverse effects, or treatment interruption. Cmin levels > 24.3 mg/L are suggested. Measurement of serum levels is useful for cases of subtherapeutic levels in standard dose treatment. | [49] |

| Population n = 44 patients | Development and validation of a method to measure daptomycin in plasma and dry plasma spots (DPS). | Bioanalytical methodology | -Stability: DPS 7 days at room temperature, 30 days at 4 °C -Retention times: 4.70 (±0.05) for daptomycin -Average recovery of plasma: 94.48% | DPS—Safe and economical option for storing and shipping plasma samples, suitable for daptomycin PK and TDM studies in hospitals without a monitoring laboratory. UPLC versus HPLC, allows a shorter analysis time, greater reproducibility, and sensitivity. | [32] | |

| HPLC-MS | Population Patients being treated for serious bacterial infections | Develop an HPLC-MS/MS method to quantify plasma concentration of 12 antibiotics. | Bioanalytical methodology | -TDM-guided dose titration in renally impaired daptomycin patients may prevent toxic rhabdomyolysis | Method developed makes it possible to adequately quantify the plasma concentration of 12 antibiotics. | [33] |

| Population n = 7, blood plasma samples | Development and validation of a method for the simultaneous extraction and quantification of daptomycin. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Retention time: 10.00 ± 0.25 min for daptomycin -No interference by other medications -Average recovery: 90.5% -Stability: room temperature for 8 h | TDM for antibacterial could be useful in special populations. Rapid, specific, sensitive, accurate, and reproducible method to measure daptomycin in human plasma. | [31] | |

| LC-MS/MS with core–shell octadecylsilyl microparticle. | Population n = 5 plasma samples | Develop an LC-MS/MS method to quantify total free daptomycin in plasma in infected patients. | Bioanalytical methodology | Lower limits: -Total daptomycin: 1.0 mcg/mL -Free daptomycin: 0.1 mcg/mL Plasma concentration ranges: -Total daptomycin: 3.01–34.1 mcg/mL -Free daptomycin: 0.39–3.64 mcg/mL -Binding to plasma proteins: 80.8–94.9% | Acceptable method for monitoring the pharmacokinetics of daptomycin in infected patients. | [20] |

| Bayesian estimation | N/A | Describe methods for antibiotic dose optimization, focus on Bayesian programs. | Review article | -Faster target concentration reach and in >% of patients with Bayesian method -Optimizing exposure to antibiotics gives better clinical results | Bayesian estimation methods are support programs. With PK/PD and clinical experience they are helpful for dose optimization. | [21] |

| MCS–TDM | Population n = 16 patients with MRSA infections | Explore the optimal daptomycin dose regimen Determine the need and validation of a high dose regimen from PK/PD parameters using Monte Carlo simulation and TDM. | Bioanalytical methodology | -Volume of distribution: 0.13 ± 0.012 L/kg (greater than that of healthy volunteers) -t1/2: 8.9 and 34.9 h (prolonged as creatinine clearance decreased) -MCS: the cumulative fraction of dose response: 6 mg/kg every 24 h: -Cmax/MIC > or equal to 60: 72% AUC/MIC > or equal to 666: 78.8% 10 mg/kg every 24 h: both 99% TDM: dose of 6 mg/kg every 24 h -Patients who reached the peak, and the AUC was: 40% (2 of 5 patients) | Intra-individual variability may indicate the need for TDM. A high dose regimen (>8 mg/kg) may be necessary to ensure treatment efficacy. | [43] |

| Population PK model | Population n = 26, patients with hemodialysis 3 times a week | Recommend doses in a standard HD schedule of three times a week for each interdialytic period. | Review article | -Interdialytic period 72 h: increase of 50% (dose >: Cmin 24.3 mg/L) -Interdialytic period 48 h: same dose (4–6 mg/kg) intra or post-HD -No patient presented elevations of CPK | More studies are needed. Intensive CPK monitoring is justifiable. | [46] |

| Dosing Protocol | Population n = 183 patients with positive cultures for VRE | Evaluate changes in daptomycin dose and adherence to the daptomycin dosing protocol and safety guidelines. | Observational retrospective study | -Average dose increased from 453 ± 144 mg to 571 ± 208 mg -Dose/weight increased 6.1 ± 1.4 mg/kg to 7.6 ± 1.6 mg/kg -Post-protocol: dose >8 mg/kg went from 4% to 52% -Dose <8 mg/kg, increased by 30% to >8 mg/kg -CPK increase: 43% to 64% -Weekly CPK monitoring for doses > 8 mg/kg | A dosing protocol requires closer monitoring to avoid the development of side effects. | [50] |

| N/A | Population -Age: 45 years -Backg: obesity -Patho: bacteremia | Prove the importance of TDM in the antimicrobial therapy of special populations. | Case report | -Blood cultures persisted positive after 14 days -Management was adjusted and TDM of daptomycin was started -The effective doses were 14 mg/kg of lean body weight for daptomycin | Multidisciplinary management based on TDM in the antimicrobial treatment of special populations was demonstrated. | [27] |

| N/A | Population -n = 122 -Spanish patients admitted to ICU | Describe the characteristics of daptomycin in Spanish ICU patients. | Review article | -Use: 85.7% of cases as rescue treatment -Dose: 6 mg/kg/day in 52% -Duration: 10.2 days -Overall clinical efficacy of 73.7% | It is a new option and a good alternative for the treatment of serious Gram-positive infections in critically ill patients. | [15] |

| Parameter | Results |

|---|---|

| No. of publications per year | 2008: 1 [22] 2009: 1 [25] 2010: 5 [8,15,35,37,46] 2011: 2 [30,44] 2012: 3 [30,47,51] 2013: 6 [23,32,36,39,44,48] 2014: 1 [48] 2015: 3 [38,42,49] 2016: 3 [7,25,33] 2017: 2 [17,39] 2018: 4 [16,18,22,24] 2019: 4 [26,43,45,50] 2020: 4 [6,21,40,52] |

| Study design type | Letter to the editor: 1 [22] Poster: 2 [25,26] Case report: 4 [27,28,29,30] Bioanalytical method: 18 [8,16,20,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45] Review article: 9 [6,7,15,21,23,24,46,47,48] Observational prospective study: 2 [17,18] Observational retrospective study: 2 [49,50] Non-randomized clinical study: 1 [19] |

| Therapeutic drug monitoring method | 1. Liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): 8 articles [16,22,25,29,33,37,42,46] 2. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC): 7 articles [8,18,23,28,30,41,47]. 3. Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM): 5 articles [19,27,32,34,49]. 4. Ultrahigh pressure liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry method (UHPLC-MS/MS): 4 articles [38,39,43,44]. 5. Ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography with UV detection (HPLC-UV): 2 articles [17,38]. 6. High performance liquid chromatography with ultraviolet detection (HPLC-UV) and liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): 2 articles [6,7]. 7. Ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography equipped with a photodiode array (UHPLC-PDA): 2 articles [32,49]. 8. Liquid chromatography using a core-layer octadecylsilyl microparticle coupled to tandem mass spectrometry: 1 article [20]. 9. Bayesian estimation 1 article [21]. 10. Dosing protocols: 1 article [50]. 11. Monte Carlo and TDM simulations: 1 article [43]. 12. Population PK models: 1 article [46]. |

| Cmax | 58.9 mg/L [49] 109.15 mg/L [16] 52.8 mg/L [8] 66.2 mg/L [40] 62.2 mg/L [6] 66.1 mg/L [6] 78.5 mg/L [6] Average: 70.55 mg/L |

| Cmin | 18.6 mg/L [49] 12.5 mg/L [8] 16,7 mg/L [40] 14 mg/L [44] 4 mg/L [45] Average: 13.16 mg/L |

| AUC/MIC | 786.93 ± 451.65 [19] Dose: 6 mg/kg/day [19]: 692 ± 210 406.09 ± 175.2 510.1 ± 129.3 962.6 ± 225.3 Average: 642.69 Dose: 8 mg/kg/day [19] 903 ± 280 (8 mg/kg) [18] 654.5 ± 312.7 584.3 ± 367.2 1013.6 ± 324.9 Average: 788.85 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Osorio, C.; Garzón, L.; Jaimes, D.; Silva, E.; Bustos, R.-H. Impact on Antibiotic Resistance, Therapeutic Success, and Control of Side Effects in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) of Daptomycin: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10030263

Osorio C, Garzón L, Jaimes D, Silva E, Bustos R-H. Impact on Antibiotic Resistance, Therapeutic Success, and Control of Side Effects in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) of Daptomycin: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics. 2021; 10(3):263. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10030263

Chicago/Turabian StyleOsorio, Carolina, Laura Garzón, Diego Jaimes, Edwin Silva, and Rosa-Helena Bustos. 2021. "Impact on Antibiotic Resistance, Therapeutic Success, and Control of Side Effects in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) of Daptomycin: A Scoping Review" Antibiotics 10, no. 3: 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10030263

APA StyleOsorio, C., Garzón, L., Jaimes, D., Silva, E., & Bustos, R.-H. (2021). Impact on Antibiotic Resistance, Therapeutic Success, and Control of Side Effects in Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) of Daptomycin: A Scoping Review. Antibiotics, 10(3), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/antibiotics10030263