Nucleic Acid-Based Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Basic Structure and Working Principles of NA-FET Biosensor

2.1. The Basic Structure of Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors

2.2. Performance Parameters of NA-FET Biosensors

2.3. Sensing Mechanisms of NA-FET Biosensors

2.4. Performance Evaluation Indicators of NA-FET Biosensors

3. Nucleic Acid Probe

3.1. Single-Stranded Nucleic Acid Probes

3.2. Framework Nucleic Acid Nanoprobes

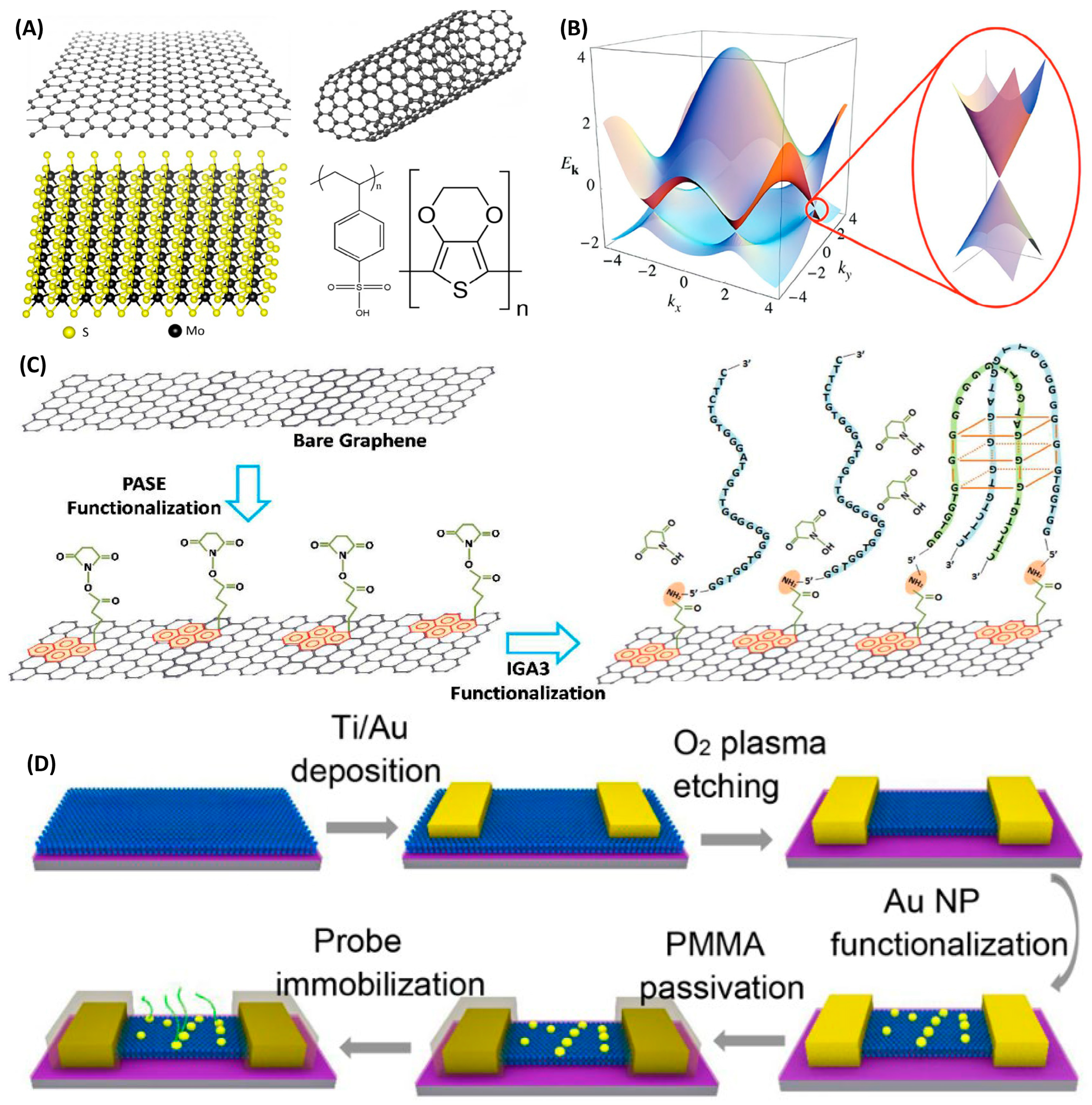

4. Channel Materials

4.1. Carbon Nanomaterials

4.1.1. Graphene

4.1.2. Carbon Nanotubes

4.2. Metallic Compound

4.3. Organic Polymer Materials

5. Clinical Diagnosis and Point-of-Care Applications

5.1. Biomarker Detection in Disease Diagnosis

5.1.1. Nucleic Acid Detection

5.1.2. Protein Detection

5.1.3. Small-Molecule Detection

5.2. Point-of-Care and In Situ Applications

5.2.1. Portable Testing

5.2.2. Wearable Sensing

5.2.3. Implantable Sensing

6. Conclusions and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FET | Field-Effect Transistor |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic Acid |

| GFET | Graphene Field-Effect Transistor |

| RNA | Ribonucleic Acid |

| CNT | Carbon Nanotube |

| LOD | Limit of Detection |

| NA-FET | Nucleic Acid-Based Field-Effect Transistor |

| EDL | Electrical Double-Layer |

| PASE | 1-pyrenebutyric acid N-succinimidyl ester |

| PNAs | Peptide Nucleic Acids |

| SWCNTs | Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes |

| PMMA | Polymethyl methacrylate |

| PDMS | Polydimethylsiloxane |

| PVA | Polyvinyl Alcohol |

| SMCC | N-SucciniMidyl 4-(N-MaleiMidoMethyl)cyclohexane-1-carboxylate |

| MBS | 3-MaleimidobenzoicacidN-hydroxysuccinimideester |

| PSA | Prostate-Specific Antigen |

References

- Broza, Y.Y.; Zhou, X.; Yuan, M.; Qu, D.; Zheng, Y.; Vishinkin, R.; Khatib, M.; Wu, W.; Haick, H. Disease Detection with Molecular Biomarkers: From Chemistry of Body Fluids to Nature-Inspired Chemical Sensors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 11761–11817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, L.C., Jr.; Lyons, C. Electrode Systems for Continuous Monitoring in Cardiovascular Surgery. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1962, 102, 29–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Chen, Y.; Song, L.; Su, Z.; Zhang, H. Advances in the Application of Field Effect Transistor Biosensor in Biomedical Detection. China Biotechnol. 2021, 41, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S.; Dastgeer, G.; Shazad, Z.M.; Zulfiqar, M.W.; Rasheed, A.; Iqbal, M.Z.; Hussain, K.; Rabani, I.; Kim, D.; Irfan, A.; et al. 2D Materials in Advanced Electronic Biosensors for Point-of-Care Devices. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, 2401386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nisar, S.; Dastgeer, G.; Shahzadi, M.; Shahzad, Z.M.; Elahi, E.; Irfan, A.; Eom, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, D. Gate-Assisted MoSe2 Transistor to Detect the Streptavidin via Supporter Molecule Engineering. Mater. Today Nano 2023, 24, 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaisti, M. Detection Principles of Biological and Chemical FET Sensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 98, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, D.; He, W.; Chen, N.; Zhou, L.; Yu, L.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, Q. Interface-engineered Field-effect Transistor Electronic Devices for Biosensing. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2306252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, M.A.D.; Reinstein, O.; Saad, M.; Johnson, P.E. Defining the Secondary Structural Requirements of a Cocaine-Binding Aptamer by a Thermodynamic and Mutation Study. Biophys. Chem. 2010, 153, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sameiyan, E.; Bagheri, E.; Ramezani, M.; Alibolandi, M.; Abnous, K.; Taghdisi, S.M. DNA Origami-Based Aptasensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2019, 143, 111662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseini, M.; Khabbaz, H.; Dadmehr, M.; Ganjali, M.R.; Mohamadnejad, J. Aptamer-Based Colorimetric and Chemiluminescence Detection of Aflatoxin B1 in Foods Samples. Acta Chim. Slov. 2015, 62, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dey, S.; Fan, C.; Gothelf, K.V.; Li, J.; Lin, C.; Liu, L.; Liu, N.; Nijenhuis, M.A.D.; Saccà, B.; Simmel, F.C.; et al. DNA Origami. Nat. Rev. Methods Primers 2021, 1, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koirala, D.; Shrestha, P.; Emura, T.; Hidaka, K.; Mandal, S.; Endo, M.; Sugiyama, H.; Mao, H. Single-Molecule Mechanochemical Sensing Using DNA Origami Nanostructures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 8137–8141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, C.; Lu, S.; Mahmood, S.; Wang, J.; Sun, C.; Pang, J.; Han, L.; Liu, H. Recent Advances in Graphene Field-Effect Transistor Toward Biological Detection. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2405471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.S.; Norton, M.L. Interactions of DNA with Graphene and Sensing Applications of Graphene Field-Effect Transistor Devices: A Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2015, 853, 127–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Hu, J.-J.; Lin, S.; Wu, J.; Xia, F.; Lou, X. Field Effect Transistor Biosensors for Healthcare Monitoring. Interdiscip. Med. 2024, 2, e20240032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhowalla, M.; Jena, D.; Zhang, H. Two-Dimensional Semiconductors for Transistors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.; Liu, Y.; Wei, D. Two-Dimensional Field-Effect Transistor Sensors: The Road toward Commercialization. Chem. Rev. 2022, 122, 10319–10392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artyukhin, A.B.; Stadermann, M.; Friddle, R.W.; Stroeve, P.; Bakajin, O.; Noy, A. Controlled Electrostatic Gating of Carbon Nanotube FET Devices. Nano Lett. 2006, 6, 2080–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoorideh, K.; Chui, C.O. On the Origin of Enhanced Sensitivity in Nanoscale FET-Based Biosensors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 5111–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Lin, X.; Xu, Z.; Chu, D. Electric Double-Layer Transistors: A Review of Recent Progress. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 5641–5673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferain, I.; Colinge, C.A.; Colinge, J.-P. Multigate Transistors as the Future of Classical Metal–Oxide–Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors. Nature 2011, 479, 310–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Loan, P.T.K.; Chen, T.; Liu, K.; Chen, C.; Wei, K.; Li, L. Label-free Electrical Detection of DNA Hybridization on Graphene Using Hall Effect Measurements: Revisiting the Sensing Mechanism. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2013, 23, 2301–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Yu, Y.; Hu, Q.; Chen, S.; Nyholm, L.; Zhang, Z. Redox Buffering Effects in Potentiometric Detection of DNA Using Thiol-Modified Gold Electrodes. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2546–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, A.; Tseng, H.-C.; Chiang, H.-C.; Hsu, W.-H.; Liao, Y.-F.; Lu, S.H.-A.; Tsai, S.-Y.; Pan, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-T. Significant Elevation in Potassium Concentration Surrounding Stimulated Excitable Cells Revealed by an Aptamer-Modified Nanowire Transistor. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 6865–6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Dai, C.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, D. Molecular-Electromechanical System for Unamplified Detection of Trace Analytes in Biofluids. Nat. Protoc. 2023, 18, 2313–2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, M.; Zhang, C.; Chen, D.; Wang, J.; Ji, Y.; Liang, N.; Gao, H.; Cheng, S.; Liu, H. Ultrasensitive and Stable All Graphene Field-Effect Transistor-Based Hg2+ Sensor Constructed by Using Different Covalently Bonded RGO Films Assembled by Different Conjugate Linking Molecules. SmartMat 2021, 2, 213–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Y.; Islam, M.S.; Adamiak, M.; Shiu, S.C.-C.; Tanner, J.A.; Heddle, J.G. DNA Aptamers for the Functionalisation of DNA Origami Nanostructures. Genes 2018, 9, 571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, X.; Rotti, P.G.; DiMarco, C.; Tyler, S.R.; Zhao, X.; Engelhardt, J.F.; Hone, J.; Lin, Q. Real-Time Monitoring of Insulin Using a Graphene Field-Effect Transistor Aptameric Nanosensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 27504–27511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, M.; Yu, Z.; Wang, S.; Qiu, J.; Huang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Liang, Y.; et al. Universal Amplification-Free RNA Detection by Integrating CRISPR-Cas10 with Aptameric Graphene Field-Effect Transistor. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025, 17, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, M.; Li, J.; Xiao, B.; Ren, Z.; Li, Z.; Yu, H.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Chen, Z.; Wang, X. Ultrasensitive Label-Free DNA Detection Based on Solution-Gated Graphene Transistors Functionalized with Carbon Quantum Dots. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 3320–3327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesler, V.; Murmann, B.; Soh, H.T. Going beyond the Debye Length: Overcoming Charge Screening Limitations in next-Generation Bioelectronic Sensors. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 16194–16201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, D.; Tessarotto, M.; Salimullah, M. Plasma-Sheath Effects on the Debye Screening Problem. Phys. Plasmas 2006, 13, 032102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Bashir, R. Advances in Field-Effect Biosensors towards Point-of-Use. Nanotechnology 2023, 34, 492002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorgenfrei, S.; Chiu, C.; Gonzalez, R.L.; Yu, Y.-J.; Kim, P.; Nuckolls, C.; Shepard, K.L. Label-Free Single-Molecule Detection of DNA-Hybridization Kinetics with a Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 126–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, M.T.; Heiranian, M.; Kim, Y.; You, S.; Leem, J.; Taqieddin, A.; Faramarzi, V.; Jing, Y.; Park, I.; van der Zande, A.M.; et al. Ultrasensitive Detection of Nucleic Acids Using Deformed Graphene Channel Field Effect Biosensors. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Olsen, T.R.; Sun, N.; Zhang, W.; Pei, R.; Lin, Q. A Graphene Aptasensor for Biomarker Detection in Human Serum. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 290, 356–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maehashi, K.; Katsura, T.; Kerman, K.; Takamura, Y.; Matsumoto, K.; Tamiya, E. Label-Free Protein Biosensor Based on Aptamer-Modified Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistors. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 782–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-K.; Kim, D.-S.; Park, H.-J.; Lim, G. Detection of DNA and Protein Molecules Using an FET-Type Biosensor with Gold as a Gate Metal. Electroanalysis 2004, 16, 1912–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Gao, Y.; Han, Y.; Pang, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Han, L. Ultrasensitive Label-Free MiRNA Sensing Based on a Flexible Graphene Field-Effect Transistor without Functionalization. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2020, 2, 1090–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghamdi, W.S.; Romero Domínguez, J.; Hasan, E.; Maksudov, T.; Anthopoulos, T.D.; Alsulaiman, D. A Peptide Nucleic Acid-Functionalized Heterojunction Thin Film Transistor as a Scalable and Reusable Platform for Label-Free Detection of MicroRNA. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 36, e12490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakatsuka, N.; Abendroth, J.M.; Yang, K.-A.; Andrews, A.M. Divalent Cation Dependence Enhances Dopamine Aptamer Biosensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 9425–9435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uno, T.; Ohtake, T.; Tabata, H.; Kawai, T. Direct Deoxyribonucleic Acid Detection Using Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect Transistors Based on Peptide Nucleic Acid. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 43, L1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egholm, M.; Buchardt, O.; Christensen, L.; Behrens, C.; Freier, S.M.; Driver, D.A.; Berg, R.H.; Kim, S.K.; Norden, B.; Nielsen, P.E. PNA Hybridizes to Complementary Oligonucleotides Obeying the Watson–Crick Hydrogen-Bonding Rules. Nature 1993, 365, 566–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, D.I.; Fourcade, A.; Svinarchuk, F.; Nielsen, P.E.; Malvy, C.; Delain, E. Analysis of Various Sequence-Specific Triplexes by Electron and Atomic Force Microscopies. Biophys. J. 1998, 74, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Uno, T.; Tabata, H.; Kawai, T. Peptide−Nucleic Acid-Modified Ion-Sensitive Field-Effect Transistor-Based Biosensor for Direct Detection of DNA Hybridization. Anal. Chem. 2007, 79, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Huang, L.; Zhang, H.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.-J. Fabrication of Ultrasensitive Field-Effect Transistor DNA Biosensors by a Directional Transfer Technique Based on CVD-Grown Graphene. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 16953–16959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Wang, S.; Huang, L.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.-J. Ultrasensitive Label-Free Detection of PNA–DNA Hybridization by Reduced Graphene Oxide Field-Effect Transistor Biosensor. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 2632–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Lee, A.; Ban, D.K.; Wang, K.; Bandaru, P. Femtomolar Level-Specific Detection of Lead Ions in Aqueous Environments, Using Aptamer-Derivatized Graphene Field-Effect Transistors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 2228–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Zhang, C.; Jiang, S.; Hu, G.; Li, X.; Zou, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Wang, X.; et al. Graphene Foam Field-Effect Transistor for Ultra-Sensitive Label-Free Detection of ATP. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 284, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, D.K.; Bodily, T.; Karkisaval, A.; Dong, Y.; Natani, S.; Ramanathan, A.; Ramil, A.; Srivastava, S.; Bandaru, P.; Glinsky, G.; et al. Rapid Self-Test of Unprocessed Viruses of SARS-CoV-2 and Its Variants in Saliva by Portable Wireless Graphene Biosensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2206521119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Cao, Y.; Qu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, L. Label-Free Detection of Cu(II) in Fish Using a Graphene Field-Effect Transistor Gated by Structure-Switching Aptamer Probes. Talanta 2022, 237, 122965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhodes, D.; Lipps, H.J. G-Quadruplexes and Their Regulatory Roles in Biology. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015, 43, 8627–8637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Han, J.; Li, Y.; Fan, L.; Li, X. Aptamer-Based K+ Sensor: Process of Aptamer Transforming into G-Quadruplex. J. Phys. Chem. B 2016, 120, 6606–6611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Huang, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, B.; Tan, J.; Yuan, Q.; Yang, Y. CRISPR-mediated Profiling of Viral RNA at Single-nucleotide Resolution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2023, 62, e202304298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, A.V.; Han, D.; Shih, W.M.; Yan, H. Challenges and Opportunities for Structural DNA Nanotechnology. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 763–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Shen, J.; Ye, D.; Dong, B.; Wang, F.; Pei, H.; Wang, J.; Shi, J.; Wang, L.; Xue, W.; et al. Programming Bulk Enzyme Heterojunctions for Biosensor Development with Tetrahedral DNA Framework. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, R.P.; Schaap, I.A.T.; Tardin, C.F.; Erben, C.M.; Berry, R.M.; Schmidt, C.F.; Turberfield, A.J. Rapid Chiral Assembly of Rigid DNA Building Blocks for Molecular Nanofabrication. Science 2005, 310, 1661–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Huang, J.; Zhang, S.; Mo, F.; Su, S.; Li, Y.; Fang, L.; Deng, J.; Huang, H.; Luo, Z.; et al. Electrochemical Biosensor for DNA Methylation Detection through Hybridization Chain-Amplified Reaction Coupled with a Tetrahedral DNA Nanostructure. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 3745–3752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Zhang, W.; Duan, Q.; Yan, Q.; Fu, H.; Zhong, L.; Yi, G. Multifunctional Electrochemical Biosensor with “Tetrahedral Tripods” Assisted Multiple Tandem Hairpins Assembly for Ultra-Sensitive Detection of Target DNA. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 20046–20056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Qiu, Y.; Zhou, W.; Lu, D.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Liu, B.; Wang, W. Advancements in Functional Tetrahedral DNA Nanostructures for Multi-Biomarker Biosensing: Applications in Disease Diagnosis, Food Safety, and Environmental Monitoring. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 31, 101486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kang, H.; Huang, K.; Guo, M.; Wu, Y.; Ying, T.; Liu, Y.; Wei, D. Antibody Nanotweezer Constructing Bivalent Transistor–Biomolecule Interface with Spatial Tolerance. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 3914–3921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Kong, D.; Qiu, L.; Wu, Y.; Dai, C.; Luo, S.; Huang, Z.; Lin, Q.; Chen, H.; Xie, S.; et al. Artificial Nucleotide Aptamer-Based Field-Effect Transistor for Ultrasensitive Detection of Hepatoma Exosomes. Anal. Chem. 2022, 95, 1446–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Wang, Y.; Luo, X.; Chen, G.; Yan, S.; Bao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Lan, J.; Huang, X.; Zheng, J.; et al. A Retention-Monitoring Assay Based on Logic Profiling Nucleic Acid Framework for Accurate Identification of Extracellular Vesicles. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 15225–15233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, Q.; Wang, X.; Zhu, J.; Yin, F.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M. Tetrahedral DNA Nanostructure Based Biosensor for High-Performance Detection of Circulating Tumor DNA Using All-Carbon Nanotube Transistor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 197, 113785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Lu, R.; Ren, P.-G.; Xie, Z. Rigid DNA Frameworks Anchored Transistor Enabled Ultrasensitive Detection of Aβ-42 in Serum. Sensors 2025, 25, 3260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Feng, D.; Xu, Y.; Yin, Z.; Dou, W.; Habiba, U.E.; Pan, C.; Zhang, Z.; Mou, H.; Deng, H.; et al. DNA-Based Functionalization of Two-Dimensional MoS2 FET Biosensor for Ultrasensitive Detection of PSA. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 548, 149169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Ji, D.; Dai, C.; Kong, D.; Chen, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, M.; Liu, Y.; Wei, D. Triple-Probe DNA Framework-Based Transistor for SARS-CoV-2 10-in-1 Pooled Testing. Nano Lett. 2022, 22, 3307–3316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kong, D.; Guo, M.; Wang, L.; Gu, C.; Dai, C.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Ai, Z.; Zhang, C.; et al. Rapid SARS-CoV-2 Nucleic Acid Testing and Pooled Assay by Tetrahedral DNA Nanostructure Transistor. Nano Lett. 2021, 21, 9450–9457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Guo, M.; Gu, C.; Dai, C.; Kong, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, C.; Qu, D.; et al. Rapid and Ultrasensitive Electromechanical Detection of Ions, Biomolecules and SARS-CoV-2 RNA in Unamplified Samples. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2022, 6, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Xie, J.; Xiao, M.; Ke, Y.; Li, J.; Nie, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Z. Spherical Nucleic Acid Probes on Floating-Gate Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors for Attomolar-Level Analyte Detection. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 34391–34402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, Z.; Xie, J.; Xiao, M.; Li, J.; Peng, X.; Liu, S.; He, J.; Lin, W.; Li, X.; Ke, Y.; et al. A DNA Triangular Prism-Based Multitargeting Transistor for Ultrasensitive Detection of Respiratory Virus. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 20850–20858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, Z.; Wang, L.; Guo, Q.; Kong, D.; Wu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wei, D. Short-Wavelength Ultraviolet Dosimeters Based on DNA Nanostructure-Modified Graphene Field-Effect Transistors. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 5071–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.; Hu, W. Photogating in Low Dimensional Photodetectors. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1700323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Liu, B.; Zou, X.; Cheng, H.-M. Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth and Applications of Two-Dimensional Materials and Their Heterostructures. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 6091–6133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, N.; Zhou, W.; Jiang, X.; Hong, G.; Fu, T.-M.; Lieber, C.M. General Strategy for Biodetection in High Ionic Strength Solutions Using Transistor-Based Nanoelectronic Sensors. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 2143–2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Man, T.; Cao, Y.; Weiss, P.S.; Monbouquette, H.G.; Andrews, A.M. Flexible and Implantable Polyimide Aptamer-Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors. ACS Sens. 2022, 7, 3644–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Mallon, K.; Chen, M.; Cui, D.; Tian, F.; AlBawardi, S.; Alsaggaf, S.; Amer, M.R.; Watson, M.A.; White, M.A.; et al. In2O3 Nanoribbon-Based Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors for Ultrasensitive Detection of Exosomal Circulating microRNA with Peptide Nucleic Acid Probes. ACS Nano 2025, 19, 29726–29736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nisar, S.; Basha, B.; Dastgeer, G.; Shahzad, Z.M.; Kim, H.; Rabani, I.; Rasheed, A.; Al-Buriahi, M.S.; Irfan, A.; Eom, J.; et al. A Novel Biosensing Approach: Improving SnS2 FET Sensitivity with a Tailored Supporter Molecule and Custom Substrate. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2303654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, W.; Zhen, X.; Pei, Z.; Xue, Q.; Zhi, C.; Shi, P. Ultrathin MXene-Micropattern-Based Field-Effect Transistor for Probing Neural Activity. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 3333–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Taheri, A.; Liu, W.; Zhuo, Y.; Ma, P.; Wu, C. Detection of Bacterial Genomic DNA Fragments Using the MXene CRISPR-Cas9 Field-Effect Transistor. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2025, 8, 16410–16420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ren, R.; Pu, H.; Chang, J.; Mao, S.; Chen, J. Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors with Two-Dimensional Black Phosphorus Nanosheets. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 89, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syedmoradi, L.; Ahmadi, A.; Norton, M.L.; Omidfar, K. A Review on Nanomaterial-Based Field Effect Transistor Technology for Biomarker Detection. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Neto, A.H.; Guinea, F.; Peres, N.M.R.; Novoselov, K.S.; Geim, A.K. The Electronic Properties of Graphene. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2009, 81, 109–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, Y.; Maehashi, K.; Matsumoto, K. Label-Free Biosensors Based on Aptamer-Modified Graphene Field-Effect Transistors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 18012–18013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, E. Application of Bifunctional Reagents for Immobilization of Proteins on a Carbon Electrode Surface: Oriented Immobilization of Photosynthetic Reaction Centers. J. Electroanal. Chem. 1994, 365, 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balderston, S.; Taulbee, J.J.; Celaya, E.; Fung, K.; Jiao, A.; Smith, K.; Hajian, R.; Gasiunas, G.; Kutanovas, S.; Kim, D.; et al. Discrimination of Single-Point Mutations in Unamplified Genomic DNA via Cas9 Immobilized on a Graphene Field-Effect Transistor. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 713–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Kong, D.; Wu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Dai, C.; Chen, C.; Zhao, J.; Luo, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, Y.; et al. Catalytic Hairpin Assembly-Enhanced Graphene Transistor for Ultrasensitive miRNA Detection. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 13281–13288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Kissmann, A.-K.; Xing, H.; Hasler, R.; Kleber, C.; Knoll, W.; Schmietendorf, H.; Engler, T.; Krutzke, L.; Kochanek, S.; et al. An Aptamer-Based gFET-Sensor for Specific Quantification of Gene Therapeutic Human Adenovirus Type 5. Biosensors 2025, 15, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, B.; Lei, Y.; Tang, L.; Li, T.; Yu, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y. Acupuncture Needle-based Transistor Neuroprobe for in Vivo Monitoring of Neurotransmitter. Small 2022, 18, 2204142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, H.M.; Lamb, A.; Budhathoki-Uprety, J. Recent Advances on Applications of Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes as Cutting-Edge Optical Nanosensors for Biosensing Technologies. Nanoscale 2024, 16, 16344–16375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xiao, M.; Jin, C.; Zhang, Z. Toward the Commercialization of Carbon Nanotube Field Effect Transistor Biosensors. Biosensors 2023, 13, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Oh, D.E.; Côté, S.; Lee, C.-S.; Kim, T.H. Orientation-Guided Immobilization of Probe DNA on swCNT-FET for Enhancing Sensitivity of EcoRV Detection. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 1901–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.-Y.; Zhu, Z.; He, J.; Yang, Y.; Liang, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, M.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, Z. Mass Production of Carbon Nanotube Transistor Biosensors for Point-of-Care Tests. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 10510–10518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Yu, Y.; Xiao, M.-M.; Ni, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, G.-J. Carbon Nanotube Field-Effect Transistor Biosensor for Ultrasensitive and Label-Free Detection of Breast Cancer Exosomal miRNA21. Anal. Chem. 2021, 93, 15501–15507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruner, G. Carbon Nanotube Transistors for Biosensing Applications. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 384, 322–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, Q.; Xiao, M.; Zhong, D.; Sun, W.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Z. Ultrasensitive Monolayer MoS2 Field-Effect Transistor Based DNA Sensors for Screening of Down Syndrome. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 1437–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kwon, J.-Y. Enzyme Immobilization on Metal Oxide Semiconductors Exploiting Amine Functionalized Layer. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 19656–19661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zeng, Z.; Zhang, H. Metal Dichalcogenide Nanosheets: Preparation, Properties and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 1934–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; McCreary, A.; Briggs, N.; Subramanian, S.; Zhang, K.; Sun, Y.; Li, X.; Borys, N.J.; Yuan, H.; Fullerton-Shirey, S.K.; et al. 2D Materials Advances: From Large Scale Synthesis and Controlled Heterostructures to Improved Characterization Techniques, Defects and Applications. 2D Mater. 2016, 3, 042001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Cao, W.; Liu, W.; Lu, Z.; Zhu, D.; Chao, J.; Weng, L.; Wang, L.; Fan, C.; Wang, L. Dual-Mode Electrochemical Analysis of microRNA-21 Using Gold Nanoparticle-Decorated MoS2 Nanosheet. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 94, 552–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.M.; Shabbir, B.; Liu, J.; Wan, Z.; Walia, S.; Bao, Q.; Alan, T.; Mokkapati, S. Bisphenol a Detection Using Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS2) Field-Effect Transistor Functionalized with DNA Aptamers. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2023, 8, 2201793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wang, Z.; Gao, M.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhou, Y.; Tian, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Highly Stable and Integrable Graphene/Molybdenum Disulfide Heterojunction Field-Effect Transistor-Based miRNA Biosensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 28585–28596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J.; Li, Y.-T.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, M.-M.; Ning, Y.; Zhang, Z.-Y.; Zhang, G.-J. Molybdenum Disulfide Field-Effect Transistor Biosensor for Ultrasensitive Detection of DNA by Employing Morpholino as Probe. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018, 110, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amen, M.T.; Pham, T.T.T.; Cheah, E.; Tran, D.P.; Thierry, B. Metal-Oxide FET Biosensor for Point-of-Care Testing: Overview and Perspective. Molecules 2022, 27, 7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shariati, M.; Sadeghi, M.; Shojaei, S.H.R. Sensory Analysis of Hepatitis B Virus DNA for Medicinal Clinical Diagnostics Based on Molybdenum Doped ZnO Nanowires Field Effect Transistor Biosensor; a Comparative Study to PCR Test Results. Anal. Chim. Acta 2022, 1195, 339442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogurcovs, A.; Kadiwala, K.; Sledevskis, E.; Krasovska, M.; Plaksenkova, I.; Butanovs, E. Effect of DNA Aptamer Concentration on the Conductivity of a Water-Gated al:ZnO Thin-Film Transistor-Based Biosensor. Sensors 2022, 22, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.; Baek, S.; Song, Y.; Lee, W.-J.; Park, S. Wide-Range and Selective Detection of SARS-CoV-2 DNA via Surface Modification of Electrolyte-Gated IGZO Thin-Film Transistors. iScience 2024, 27, 109061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, C.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, D.-K.; Na, K.-S.; Kim, D.Y. Real-Time and Highly Sensitive Detection of Matrix Metalloproteinase 9 (MMP-9) in Tears Using Aptamer Functionalized Electrolyte-Gated IGZO Thin-Film Transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 38848–38858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.M.; Abendroth, J.M.; Nakatsuka, N.; Zhu, B.; Yang, Y.; Andrews, A.M.; Weiss, P.S. Detecting DNA and RNA and Differentiating Single-Nucleotide Variations via Field-Effect Transistors. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 5982–5990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Song, J.Y.; Shim, J.-E.; Kim, D.H.; Na, H.-K.; You, E.-A.; Ha, Y.-G. Highly Effective and Efficient Self-Assembled Multilayer-Based Electrode Passivation for Operationally Stable and Reproducible Electrolyte-Gated Transistor Biosensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 46527–46537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, H.; Rim, Y.S.; Wang, I.C.; Li, C.; Zhu, B.; Sun, M.; Goorsky, M.S.; He, X.; Yang, Y. Quasi-Two-Dimensional Metal Oxide Semiconductors Based Ultrasensitive Potentiometric Biosensors. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 4710–4718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aroonyadet, N.; Wang, X.; Song, Y.; Chen, H.; Cote, R.J.; Thompson, M.E.; Datar, R.H.; Zhou, C. Highly Scalable, Uniform, and Sensitive Biosensors Based on Top-down Indium Oxide Nanoribbons and Electronic Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 1943–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Cheung, K.M.; Huang, I.-W.; Yang, H.; Nakatsuka, N.; Liu, W.; Cao, Y.; Man, T.; Weiss, P.S.; Monbouquette, H.G.; et al. Implantable Aptamer–Field-Effect Transistor Neuroprobes for in Vivo Neurotransmitter Monitoring. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, eabj7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Zhao, C.; Wang, Z.; Yang, K.-A.; Cheng, X.; Liu, W.; Yu, W.; Lin, S.; Zhao, Y.; Cheung, K.M.; et al. Wearable Aptamer-Field-Effect Transistor Sensing System for Noninvasive Cortisol Monitoring. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabk0967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torsi, L.; Magliulo, M.; Manoli, K.; Palazzo, G. Organic Field-Effect Transistor Sensors: A Tutorial Review. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013, 42, 8612–8628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Jin, C.; Jiang, R.; Su, J.; Tian, T.; Yin, C.; Meng, J.; Kou, Z.; Bai, S.; Müller-Buschbaum, P.; et al. Homogeneous Coverage of the Low-Dimensional Perovskite Passivation Layer for Formamidinium–Caesium Perovskite Solar Modules. Nat. Energy 2024, 9, 1540–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magliulo, M.; Manoli, K.; Macchia, E.; Palazzo, G.; Torsi, L. Tailoring Functional Interlayers in Organic Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors. Adv. Mater. 2015, 27, 7528–7551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mai, R.; Zhou, Y.; Zhao, K.; Xie, M.; Tang, Y.; Li, X.; Huang, W.; Xiang, L. Biosensors Based on Organic Transistors for Intraoral Biomarker Detection. Microchim. Acta 2025, 192, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, R.S.; McConnell, E.M.; Chan, D.; Holahan, M.R.; DeRosa, M.C.; Prakash, R. Non-Invasive Monitoring of α-Synuclein in Saliva for Parkinson’s Disease Using Organic Electrolyte-Gated FET Aptasensor. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 3116–3126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, M.; Greco, P.; Sensi, M.; Saygin, G.D.; Bellassai, N.; D’Agata, R.; Spoto, G.; Biscarini, F. Label Free Detection of miRNA-21 with Electrolyte Gated Organic Field Effect Transistors (EGOFETs). Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 182, 113144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Shi, W.; Song, J.; Jang, H.-J.; Dailey, J.; Yu, J.; Katz, H.E. Chemical and Biomolecule Sensing with Organic Field-Effect Transistors. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 3–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Wang, X.; Gu, C.; Guo, M.; Wang, Y.; Ai, Z.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y.; Liu, W.; Wu, Y.; et al. Direct SARS-CoV-2 Nucleic Acid Detection by Y-Shaped DNA Dual-Probe Transistor Assay. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 17004–17014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Li, D.; Liu, J.; Hou, S.; Yang, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Li, F.; Hao, Z.; et al. A Flexible Aptameric Graphene Field-effect Nanosensor Capable of Automatic Liquid Collection/Filtering for Cytokine Storm Biomarker Monitoring in Undiluted Sweat. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2309447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y.; Kuai, Y.; Li, R.; Xu, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Chen, S.; Guo, M.; et al. Aptamer-Mediated Artificial Synapses for Neuromorphic Modulation of Inflammatory Signaling via Organic Electrochemical Transistor. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e09545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Yi, Z.; Liu, X.; Wu, Y.; Fang, C.; Ge, Z.; He, Y.; Li, S.; Xie, X.; Zhang, L.; et al. Engineering 3D Microtip Gates of All-Polymer Organic Electrochemical Transistors for Rapid Femtomolar Nucleic-Acid-Based Saliva Testing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2025, 273, 117170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, L.; Dong, B.; Mao, Y.; Qu, H.; Zheng, L. Selective Detection of Pb2+ Ions Based on a Graphene Field-Effect Transistor Gated by DNAzymes in Binding Mode. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2023, 237, 115549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sempionatto, J.R.; Lasalde-Ramírez, J.A.; Mahato, K.; Wang, J.; Gao, W. Wearable Chemical Sensors for Biomarker Discovery in the Omics Era. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2022, 6, 899–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravariu, C. From Enzymatic Dopamine Biosensors to OECT Biosensors of Dopamine. Biosensors 2023, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavecchia di Tocco, F.; Botti, V.; Cannistraro, S.; Bizzarri, A.R. Detection of miR-155 Using Peptide Nucleic Acid at Physiological-like Conditions by Surface Plasmon Resonance and Bio-Field Effect Transistor. Biosensors 2024, 14, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Q.; Jiang, L.; Ma, S.; Li, T.; Zhu, Y.; Qiu, R.; Xing, Y.; Yin, F.; Li, Z.; Ye, X.; et al. Multi-Body Biomarker Entrapment System: An All-Encompassing Tool for Ultrasensitive Disease Diagnosis and Epidemic Screening. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35, 2304119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B.; Li, T.; Cao, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, J.; Xiao, M.; Zhang, Z. In Situ Electrically Resettable Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors for Continuous and Multiplexed Neurotransmitter Detection. Adv. Sci. 2025, 12, e04497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalluri, R.; LeBleu, V.S. The Biology, Function, and Biomedical Applications of Exosomes. Science 2020, 367, eaau6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Park, H.; Kim, J.; Park, H.; Kim, T.-H.; Park, C.; Kim, J.; Lee, M.-H.; Lee, T. Extended-Gate Field-Effect Transistor Consisted of a CD9 Aptamer and MXene for Exosome Detection in Human Serum. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 3174–3186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.-X.; Li, Y.-L. Recent Advances in Detection Methods for Neurotransmitters. Chin. J. Anal. Chem. 2020, 48, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, E.K.; Vrshek-Schallhorn, S.; Kendall, A.D.; Mineka, S.; Zinbarg, R.E.; Craske, M.G. Prospective Associations between the Cortisol Awakening Response and First Onsets of Anxiety Disorders over a Six-Year Follow-up—2013 Curt Richter Award Winner. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2014, 44, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Baek, S.; Sen, A.; Jung, B.; Shim, J.; Park, Y.C.; Lee, L.P.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, S. Ultrasensitive and Selective Field-Effect Transistor-Based Biosensor Created by Rings of MoS2 Nanopores. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 1826–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Xu, C.; Zhang, S.; Chen, S.; Wang, H.; Duan, Z.; Al-Hartomy, O.A.; Wageh, S.; Wen, X.; Liu, Y.; et al. Rapid and Ultrasensitive Detection of Mpox Virus Using CRISPR/Cas12b-Empowered Graphene Field-Effect Transistors. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2023, 10, 031409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Liu, L.; Yuan, J.; Wu, L.; Lei, S. Recent Advances in Field Effect Transistor Biosensors: Designing Strategies and Applications for Sensitive Assay. Biosensors 2023, 13, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, Z.; Jia, Y.; Wang, F.; Tian, J.; Zhang, C.; Han, T.; Xing, R.; Ye, W.; Wang, C. Observing Mesoscopic Nucleic Acid Capacitance Effect and Mismatch Impact via Graphene Transistors. Small 2022, 18, 2105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Fang, Y. Flexible and Implantable Microelectrodes for Chronically Stable Neural Interfaces. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1804895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, T. Flexible Sensing Electronics for Wearable/Attachable Health Monitoring. Small 2017, 13, 1602790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-C.; Lin, Y.-C.; Yeh, C.-H.; Huang, J.-C.; Chiu, P.-W. High Mobility Flexible Graphene Field-Effect Transistors with Self-Healing Gate Dielectrics. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 4469–4474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakatsuka, N.; Yang, K.-A.; Abendroth, J.M.; Cheung, K.M.; Xu, X.; Yang, H.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, B.; Rim, Y.S.; Yang, Y.; et al. Aptamer–Field-Effect Transistors Overcome Debye Length Limitations for Small-Molecule Sensing. Science 2018, 362, 319–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishikawa, F.N.; Curreli, M.; Chang, H.-K.; Chen, P.-C.; Zhang, R.; Cote, R.J.; Thompson, M.E.; Zhou, C. A Calibration Method for Nanowire Biosensors to Suppress Device-to-Device Variation. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 3969–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target Type | Target | Probe Type | Channel Material | Modification Methods | LOD | Response Time | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleic Acid | RSVRNA | Framework nucleic acid with ssDNA probes | CNT | -SH | 0.1 copies/μL | ~40 s | [71] |

| miRNA-141 | PNA | In2O3/ZnO | Phosphonic acid anchor groups | 0.6 fM | 2 h | [40] | |

| miRNA-21 | ssDNA | CNT | Au-S | 0.87 aM | - | [94] | |

| miRNA-21 | Framework nucleic acid with ssDNA probes | Graphene | PASE | 5.67 × 10−19 M | 1 h | [87] | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | CRISPR-Cas system | IGZO | SMCC | 1 cp μL−1 | ~20 min | [54] | |

| E. coli gene | CRISPR-Cas system | Graphene-MXene | APTES | - | 1 h | [80] | |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Framework nucleic acid | Graphene | PASE | 0.03 copy/μL | ~40 s | [122] | |

| miR-200b | PNA | In2O3 | (10-BRomodecyl)phosphonic acid | 0.72 aM | 5 min | [77] | |

| Protein | miRNA-155 | CRISPR-Cas system | Graphene | Au-S | 427 aM | 45 min | [29] |

| SOD1 gene | CRISPR-Cas system | Graphene | PBA | 6.3 fM | 40 min | [86] | |

| TNF-α | Aptamer | Graphene | PASE | 0.31 pM | - | [123] | |

| CD63, EpCAM, MUC1 | Framework nucleic acid with ssDNA probes | Au | Au-S | 5.35 × 107 particles/mL | 4.5 h | [63] | |

| SARS-CoV-2 spike protein | Framework nucleic acid with nanobodies | Graphene | PASE | 0.5 aM | ~50 s | [61] | |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | Aptamer | PEDOT:PSS | Au-S | 0.5 pM | A few minutes | [124] | |

| HepG2 exosomes Protein | framework nucleic acid with aptamer | Graphene | PASE | 242 particles/mL | 9 min | [62] | |

| Small biomolecules | PSA | Framework nucleic acid | MoS2 | Au-S | 1 fg/mL | ~2 min | [66] |

| Dopamine | Aptamer | Graphene | PASE | 370 pM | Immediate | [89] | |

| BPA | Aptamer/dsDNA | MoS2 | Au-S | 1 pg/mL | 4 s | [101] | |

| Dopamine and Serotonin | Aptamer | In2O3 | MBS | 1 nM to 1 μM | - | [41] | |

| Progesterone | Aptamer | PEDOT:PSS. | Au-S | 0.5 fM | ~5 min | [125] | |

| ATP | Spherical Nucleic Acids | CNT | Au-O | 0.55 ag mL−1 | 100 s | [70] | |

| Metal ion | Hg2+ | ssDNA | Graphene | Au-S | 16 pM | 15 min | [26] |

| Pb2+ | dsDNA | Graphene | Au-S | 1.9 nM | - | [126] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Fan, H.; Ye, D.; Gao, X.; Luo, Y.; Wang, L. Nucleic Acid-Based Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors. Biosensors 2026, 16, 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020095

Fan H, Ye D, Gao X, Luo Y, Wang L. Nucleic Acid-Based Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors. Biosensors. 2026; 16(2):95. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020095

Chicago/Turabian StyleFan, Haoyu, Dekai Ye, Xiuli Gao, Yuan Luo, and Lihua Wang. 2026. "Nucleic Acid-Based Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors" Biosensors 16, no. 2: 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020095

APA StyleFan, H., Ye, D., Gao, X., Luo, Y., & Wang, L. (2026). Nucleic Acid-Based Field-Effect Transistor Biosensors. Biosensors, 16(2), 95. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16020095