A Wearable Ultrasound Sensing System for Soft Tissue Stiffness Detection: A Feasibility Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Design, Optimization, and Testing of the Wearable Ultrasound Sensing System

2.1. Architecture and Operating Principle of the Wearable Ultrasound Sensing System

2.2. Measurement of Silicone Sample Stiffness Using Ultrasonic Transducers

2.3. The Measurement of the Stiffness of Isolated Animal Tissue by Means of Ultrasonic Transducers

2.4. Design of the Wearable Soft Tissue Stiffness Sensing System

3. Application Study of the Wearable Soft Tissue Stiffness Sensing System

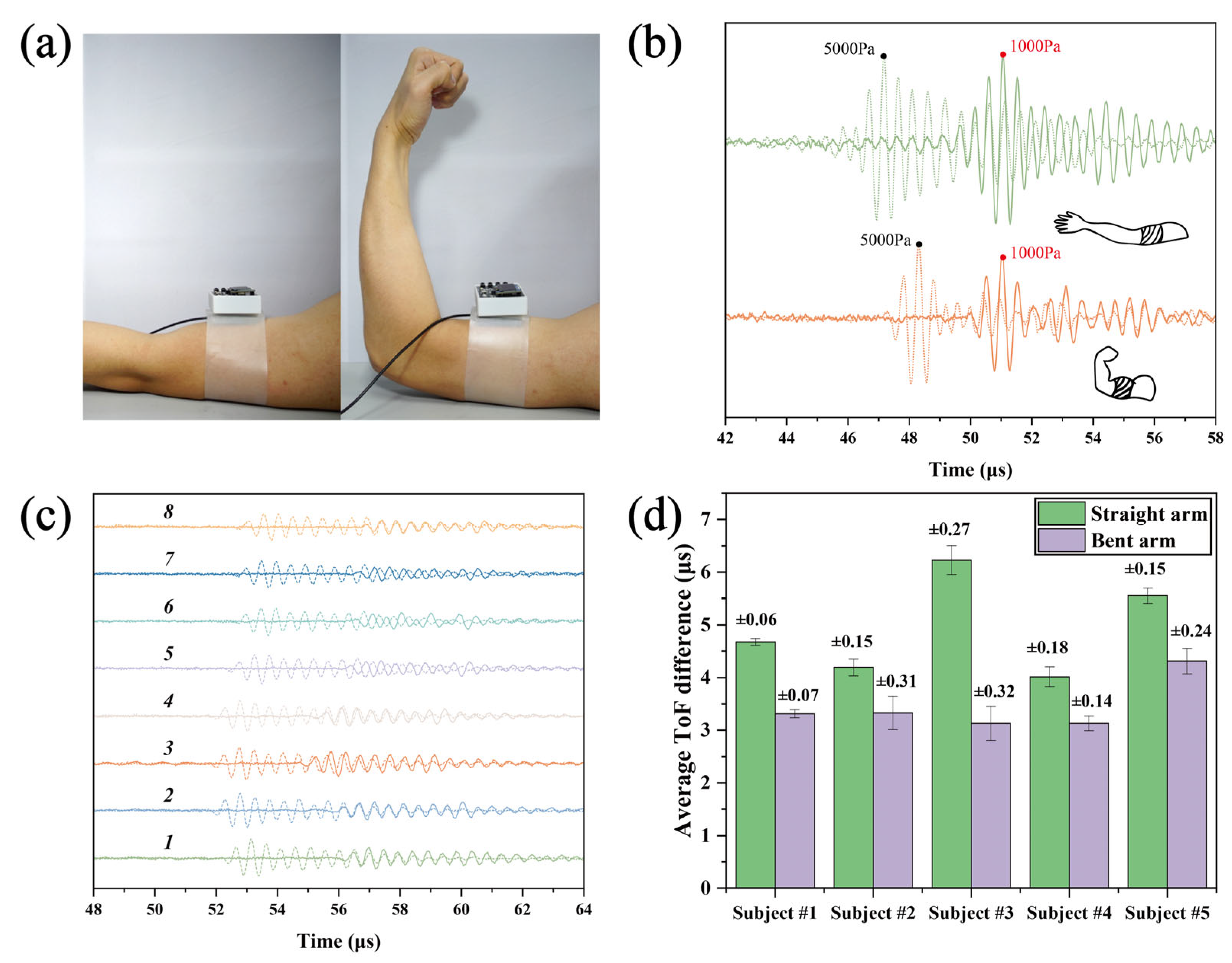

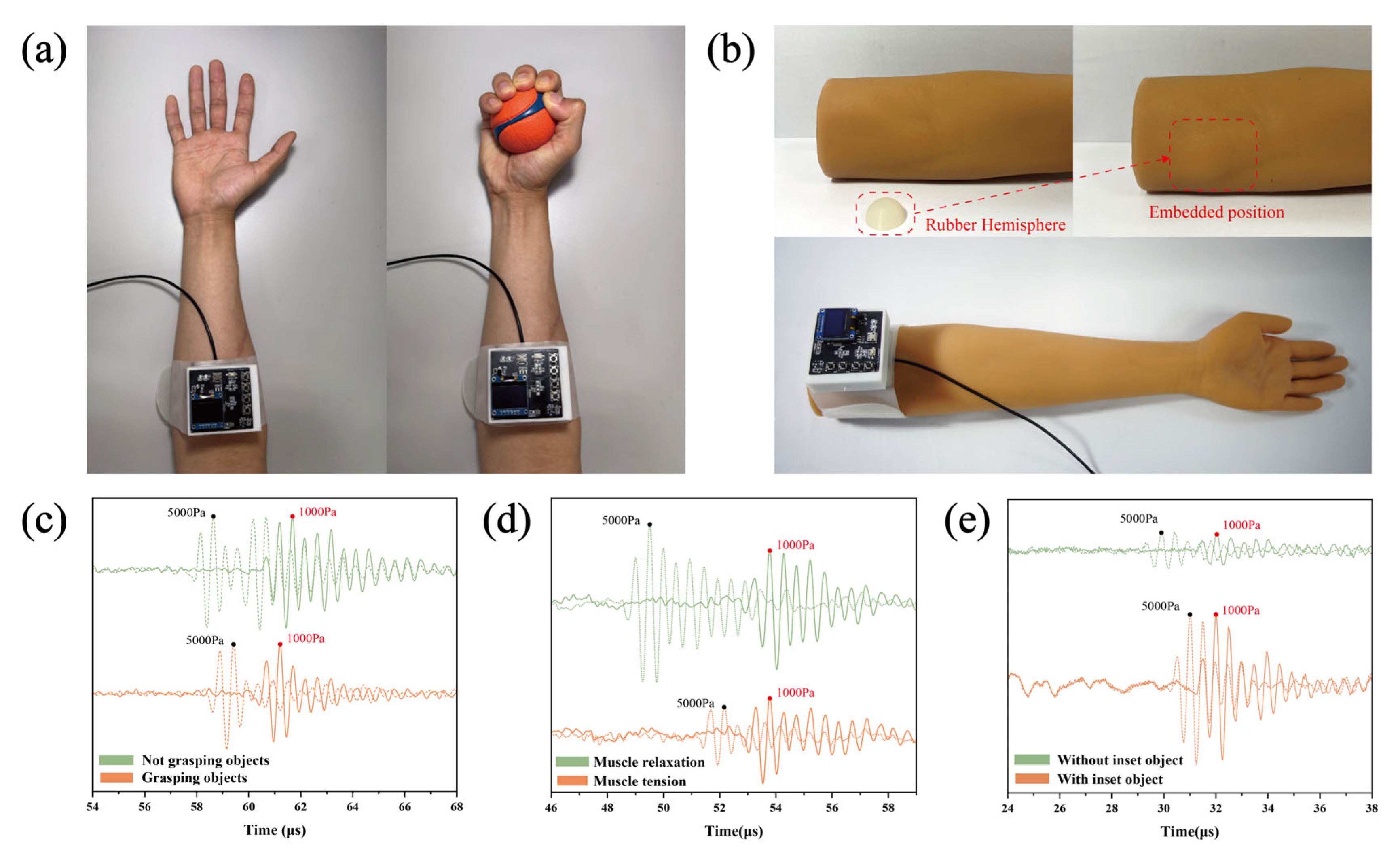

3.1. Stiffness Discrimination in Biceps Brachii: Extended vs. Flexed Arm States

3.2. Assessment of Forearm and Thigh Stiffness and Identification of Simulated Pathological Tissues in Arm Models

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xu, C.H.; Song, Y.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Solomon, S.A.; Yu, Y.; Nyein, H.Y.Y.; Tay, R.Y.; Li, J.H.; Heng, W.Z.; Min, J.H.; et al. A physicochemical-sensing electronic skin for stress response monitoring. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Campbell, A.S.; Wang, J. Wearable non-invasive epidermal glucose sensors: A review. Talanta 2018, 177, 163–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ling, Y.Z.; An, T.C.; Yap, L.W.; Zhu, B.W.; Gong, S.; Cheng, W.L. Disruptive, Soft, Wearable Sensors. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1904664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahato, K.; Saha, T.; Ding, S.C.; Sandhu, S.S.; Chang, A.Y.; Wang, J.S. Hybrid multimodal wearable sensors for comprehensive health monitoring. Nat. Electron. 2024, 7, 735–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymourian, H.; Parrilla, M.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Montiel, N.F.; Barfidokht, A.; Van Echelpoel, R.; De Wael, K.; Wang, J. Wearable Electrochemical Sensors for the Monitoring and Screening of Drugs. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 2679–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.H.; Xianyu, Y.L. Gold Nanomaterials-Implemented Wearable Sensors for Healthcare Applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2113012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, H.C.; Nguyen, P.Q.; Gonzalez-Macia, L.; Morales-Narváz, E.; Guder, F.; Collins, J.J.; Dincer, C. End-to-end design of wearable sensors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 887–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brasier, N.; Wang, J.; Gao, W.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Dincer, C.; Ates, H.C.; Güder, F.; Olenik, S.; Schauwecker, I.; Schaffarczyk, D.; et al. Applied body-fluid analysis by wearable devices. Nature 2024, 636, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savoia, A.S.; Caliano, G.; Pappalardo, M. A CMUT Probe for Medical Ultrasonography: From Microfabrication to System Integration. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2012, 59, 1127–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shung, K.K.; Cannata, J.M.; Zhou, Q.F. Piezoelectric materials for high frequency medical imaging applications: A review. J. Electroceram. 2007, 19, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothberg, J.M.; Ralston, T.S.; Rothberg, A.G.; Martin, J.; Zahorian, J.S.; Alie, S.A.; Sanchez, N.J.; Chen, K.L.; Chen, C.; Thiele, K.; et al. Ultrasound-on-chip platform for medical imaging, analysis, and collective intelligence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2019339118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattain, L.J.; Telfer, B.A.; Dhyani, M.; Grajo, J.R.; Samir, A.E. Machine learning for medical ultrasound: Status, methods, and future opportunities. Abdom. Radiol. 2018, 43, 786–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.F.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Lei, B.Y.; Liu, L.; Li, S.X.; Ni, D.; Wang, T.F. Deep Learning in Medical Ultrasound Analysis: A Review. Engineering 2019, 5, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.A. Medical ultrasound imaging. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2007, 93, 153–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, D.J.A.; Wallbridge, D.R.; Stewart, M.J. Tissue Doppler imaging: Current and potential clinical applications. Heart 2000, 84, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poelma, C. Ultrasound Imaging Velocimetry: A review. Exp. Fluids 2017, 58, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, J.; Kremkau, F. Medical ultrasound systems. Interface Focus 2011, 1, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Park, G.; Lin, M.; Yang, X.; Xu, S. Wearable ultrasound technology. Nat. Rev. Bioeng. 2025, 3, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sempionatto, J.R.; Lin, M.; Yin, L.; De la Paz, E.; Pei, K.; Sonsa-Ard, T.; de Loyola Silva, A.N.; Khorshed, A.A.; Zhang, F.; Tostado, N.; et al. An epidermal patch for the simultaneous monitoring of haemodynamic and metabolic biomarkers. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 737–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, M.Y.; Zhang, Z.Y.; Gao, X.X.; Bian, Y.Z.; Wu, R.S.; Park, G.; Lou, Z.Y.; Zhang, Z.R.; Xu, X.C.; Chen, X.J.; et al. A fully integrated wearable ultrasound system to monitor deep tissues in moving subjects. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 448–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.W.K.; Jeong, J.; Hsieh, J.-C.; Yao, M.; Ding, H.; Wang, W.; Liu, X.; Pyatnitskiy, I.; He, W.; Moscoso-Barrera, W.D.; et al. Bioadhesive hydrogel-coupled and miniaturized ultrasound transducer system for long-term, wearable neuromodulation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Q.F.; Dong, B.W.; He, T.Y.Y.; Sun, Z.D.; Zhu, J.X.; Zhang, Z.X.; Lee, C. Progress in wearable electronics/photonics-Moving toward the era of artificial intelligence and internet of things. Infomat 2020, 2, 1131–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, A.; Stewart, J.; Smith, C.; Parvini, C.; McCormick, M.; Do, K.; Cartagena-Rivera, A.X. Mechanical properties of human tumour tissues and their implications for cancer development. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2024, 6, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.J.; Luo, D.; Wang, H.; Zhu, M.; Shi, Y. Missed Diagnosis of Lipohypertrophy by Inspection and Palpation: Prevalence and Contributing Risk Factors. Diabetes 2020, 69, 674-P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.Y.; Chalmers, A.N. Review of Wearable and Portable Sensors for Monitoring Personal Solar UV Exposure. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 49, 964–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arda, K.; Ciledag, N.; Aktas, E.; Aribas, B.K.; Köse, K. Quantitative Assessment of Normal Soft-Tissue Elasticity Using Shear-Wave Ultrasound Elastography. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2011, 197, 532–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, X.W.; Li, K.N.; Yi, A.J.; Wang, B.; Wei, Q.; Wu, G.G.; Dietrich, C.F. Ultrasound elastography. Endosc. Ultrasound 2022, 11, 252–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sack, I. Magnetic resonance elastography from fundamental soft-tissue mechanics to diagnostic imaging. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2023, 5, 25–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; He, X.D.; Chen, Z.P. Acoustic radiation force optical coherence elastography for elasticity assessment of soft tissues. Appl. Spectrosc. Rev. 2019, 54, 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, M.; Park, S.J.; Dauerman, H.L.; Uemura, S.; Kim, J.S.; Di Mario, C.; Johnson, T.W.; Guagliumi, G.; Kastrati, A.; Joner, M.; et al. Optical coherence tomography in coronary atherosclerosis assessment and intervention. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2022, 19, 684–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvaraj, E.A.; Mózes, F.E.; Jayaswal, A.N.A.; Zafarmand, M.H.; Vali, Y.; Lee, J.A.; Levick, C.K.; Young, L.A.J.; Palaniyappan, N.; Liu, C.H.; et al. Diagnostic accuracy of elastography and magnetic resonance imaging in patients with NAFLD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Hepatol. 2021, 75, 770–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, C.F.; Jenssen, C.; Herth, F.J.F. Endobronchial ultrasound elastography. Endosc. Ultrasound 2016, 5, 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.Y.; Ahn, J.M.; Yun, S.C.; Hur, S.H.; Cho, Y.K.; Lee, C.H.; Hong, S.J.; Lim, S.; Kim, S.W.; Won, H.; et al. Guiding Intervention for Complex Coronary Lesions by Optical Coherence Tomography or Intravascular Ultrasound. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2024, 83, 401–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.P.; Mak, A.F.T. An ultrasound indentation system for biomechanical properties assessment of soft tissues in-vivo. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1996, 43, 912–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Normal Contact of Elastic Solids—Hertz Theory. In Contact Mechanics; Johnson, K.L., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1985; pp. 84–106. [Google Scholar]

- Chao, C.Y.L.; Zheng, Y.P.; Huang, Y.P.; Cheing, G.L.Y. Biomechanical properties of the forefoot plantar soft tissue as measured by an optical coherence tomography-based air-jet indentation system and tissue ultrasound palpation system. Clin. Biomech. 2010, 25, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzetti, R.; Fantoni, G.; Gelli, F.; Faggioni, L.; Vitali, S.; Gabriele, M.; Caramella, D. Feasibility of intraoral ultrasonography in the diagnosis of oral soft tissue lesions: A preclinical assessment on an ex vivo specimen. Radiol. Medica 2018, 123, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacioni, A.; Carbone, M.; Freschi, C.; Viglialoro, R.; Ferrari, V.; Ferrari, M. Patient-specific ultrasound liver phantom: Materials and fabrication method. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2015, 10, 1065–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bao, G.; Xu, T.; Li, X.; Meng, B. A Wearable Ultrasound Sensing System for Soft Tissue Stiffness Detection: A Feasibility Study. Biosensors 2026, 16, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010009

Bao G, Xu T, Li X, Meng B. A Wearable Ultrasound Sensing System for Soft Tissue Stiffness Detection: A Feasibility Study. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleBao, Guangshuai, Tongyi Xu, Xiaoyu Li, and Bo Meng. 2026. "A Wearable Ultrasound Sensing System for Soft Tissue Stiffness Detection: A Feasibility Study" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010009

APA StyleBao, G., Xu, T., Li, X., & Meng, B. (2026). A Wearable Ultrasound Sensing System for Soft Tissue Stiffness Detection: A Feasibility Study. Biosensors, 16(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010009