Integrated Analysis of Behavioral and Physiological Effects of Nano-Sized Carboxylated Polystyrene Particles on Daphnia magna Neonates and Adults: A Video Tracking-Based Improvement of Acute Toxicity Assay

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Exposure of Neonates and Adults of Daphnia magna to Carboxylated PS Nanoparticles Under Acute Toxicity Test

2.3. Heart Rate Effects

2.4. Behavioral Effects Assessed by a Portable Smartphone-Based Platform

2.5. Confocal Microscopy Observation

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Effect of PS NPs on Daphnia magna Survival

3.2. Distribution of Carboxylated PS NPs in the Body of Daphnia magna Neonates and Adults

3.3. Effect of PS NPs on Daphnia magna Heart Rate

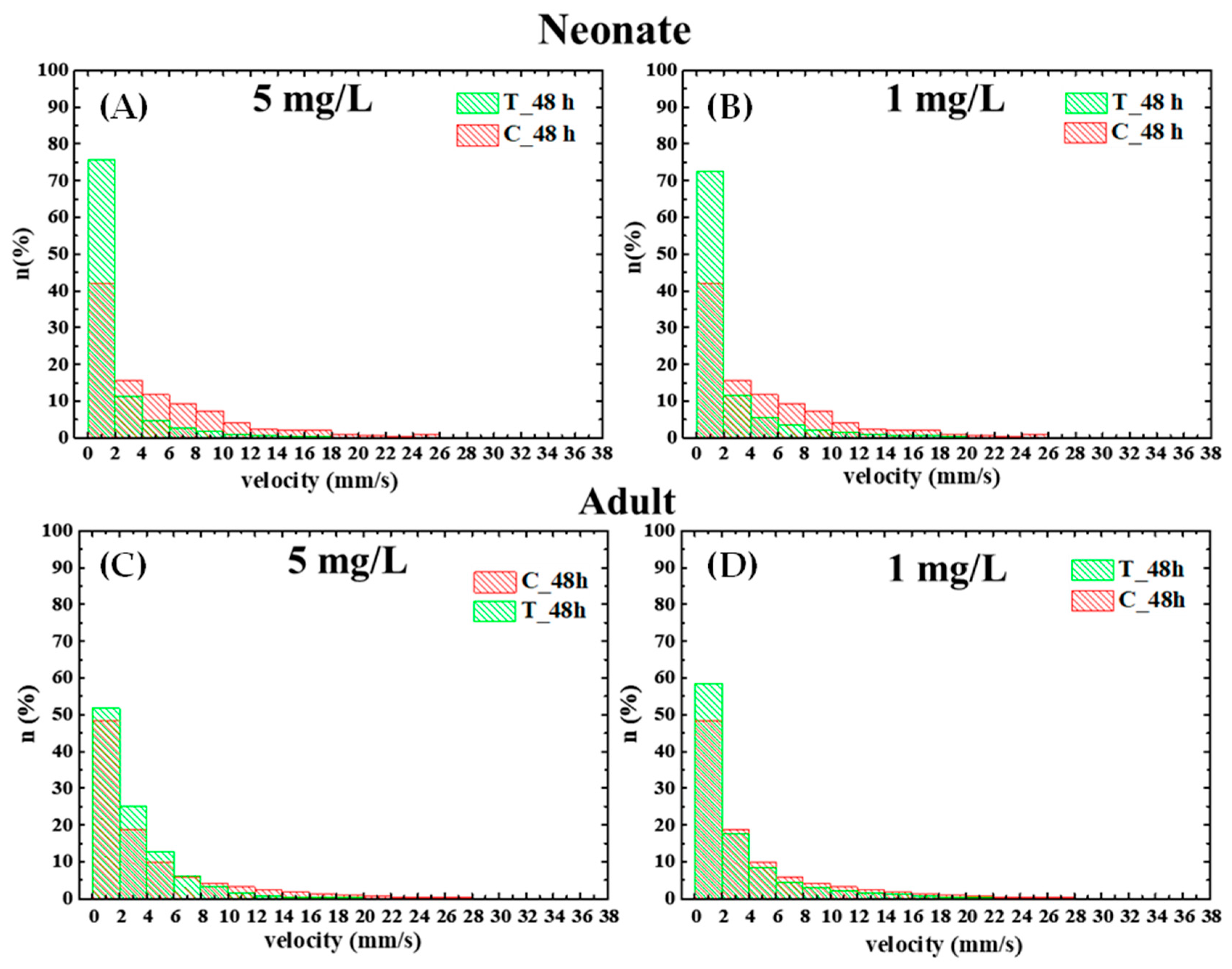

3.4. Effect of PS NPs on Daphnia magna Behavior

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mutuku, J.; Yanotti, M.; Tocock, M.; Hatton MacDonald, D. The Abundance of Microplastics in the World’s Oceans: A Systematic Review. Oceans 2024, 5, 398–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kik, K.; Bukowska, B.; Sicińska, P. Polystyrene nanoparticles: Sources, occurrence in the environment, distribution in tissues, accumulation and toxicity to various organisms. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, C.; Syrovets, T.; Musyanovych, A.; Mailänder, V.; Landfester, K.; Nienhaus, G.U.; Simmet, T. Functionalized polystyrene nanoparticles as a platform for studying bio–nano interactions. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2014, 5, 2403–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionetto, F.; Corcione, C.E.; Rizzo, A.; Maffezzoli, A. Production and Characterization of Polyethylene Terephthalate Nanoparticles. Polymers 2021, 13, 3745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.; Wagner, M. Characterisation of nanoplastics during the degradation of polystyrene. Chemosphere 2016, 145, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekvall, M.T.; Lundqvist, M.; Kelpsiene, E.; Šileikis, E.; Gunnarsson, S.B.; Cedervall, T. Nanoplastics formed during the mechanical breakdown of daily-use polystyrene products. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 1055–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionetto, F.; Lionetto, M.G.; Mele, C.; Corcione, C.E.; Bagheri, S.; Udayan, G.; Maffezzoli, A. Autofluorescence of Model Polyethylene Terephthalate Nanoplastics for Cell Interaction Studies. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo, G.; Lionetto, F.; Giordano, M.E.; Lionetto, M.G. Interaction of Micro- and Nanoplastics with Enzymes: The Case of Carbonic Anhydrase. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 9716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, E. The role of surface charge in cellular uptake and cytotoxicity of medical nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2012, 7, 5577–5591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salvati, A.; Åberg, C.; dos Santos, T.; Varela, J.; Pinto, P.; Lynch, I.; Dawson, K.A. Experimental and theoretical comparison of intracellular import of polymeric nanoparticles and small molecules: Toward models of uptake kinetics. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 2011, 7, 818–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Liddle, C.; Consolandi, G.; Drago, C.; Hird, C.; Lindeque, P.K.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastics, microfibres and nanoplastics cause variable sub-lethal responses in mussels (Mytilus spp.). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 160, 111552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Torre, C.; Bergami, E.; Salvati, A.; Faleri, C.; Cirino, P.; Dawson, K.A.; Corsi, I. Accumulation and embryotoxicity of polystyrene nanoparticles at early stage of development of sea urchin embryos Paracentrotus lividus. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2014, 48, 12302–12311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Besseling, E.; Quik, J.T.K.; Sun, M.; Koelmans, A.A. Fate of nano- and microplastic in freshwater systems: A modeling study. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 540–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koelmans, A.A.; Mohamed Nor, N.H.; Hermsen, E.; Kooi, M.; Mintenig, S.M.; De France, J. Microplastics in freshwaters and drinking water: Critical review and assessment of data quality. Water Res. 2019, 155, 410–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkola, A.; Krause, S.; Lynch, I.; Sambrook Smith, G.H.; Nel, H. Nano and microplastic interactions with freshwater biota—Current knowledge, challenges and future solutions. Environ. Int. 2021, 152, 106504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Fileman, E.; Halsband, C.; Goodhead, R.; Moger, J.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastic Ingestion by Zooplankton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 6646–6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikuda, O.; Dumont, E.R.; Matthews, S.; Xu, E.G.; Berk, D.; Tufenkji, N. Sub-lethal effects of nanoplastics upon chronic exposure to Daphnia magna. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikuda, O.; Roubeau Dumont, E.; Chen, Q.; Macairan, J.-R.; Robinson, S.A.; Berk, D.; Tufenkji, N. Toxicity of microplastics and nanoplastics to Daphnia magna: Current status, knowledge gaps and future directions. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 167, 117208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, B.; Sugni, M.; Casati, L.; Parolini, M. Molecular, biochemical and behavioral responses of Daphnia magna under long-term exposure to polystyrene nanoplastics. Environ. Int. 2022, 164, 107264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pochelon, A.; Stoll, S.; Slaveykova, V.I. Polystyrene Nanoplastic Behavior and Toxicity on Crustacean Daphnia magna: Media Composition, Size, and Surface Charge Effects. Environments 2021, 8, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Cai, M.; Yu, P.; Chen, M.; Wu, D.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Y. Age-dependent survival, stress defense, and AMPK in Daphnia pulex after short-term exposure to a polystyrene nanoplastic. Aquat Toxicol 2018, 204, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, W.; Jiang, R.; Hu, S.; Xiao, X.; Wu, J.; Wei, S.; Xiong, Y.; Ouyang, G. Investigating the toxicities of different functionalized polystyrene nanoplastics on Daphnia magna. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 180, 509–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosner, A.; Ballarin, L.; Barnay-Verdier, S.; Borisenko, I.; Drago, L.; Drobne, D.; Concetta Eliso, M.; Harbuzov, Z.; Grimaldi, A.; Guy-Haim, T.; et al. A broad-taxa approach as an important concept in ecotoxicological studies and pollution monitoring. Biol. Rev. Camb. Philos. Soc. 2024, 99, 131–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Test No. 202: Daphnia sp. Acute Immobilisation Test, OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals; Section 2; OECD: Paris, France, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete-Kertész, I.; László, K.; Terebesi, C.; Gyarmati, B.S.; Farah, S.; Márton, R.; Molnár, M. Ecotoxicity Assessment of Graphene Oxide by Daphnia magna through a Multimarker Approach from the Molecular to the Physiological Level including Behavioral Changes. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bownik, A. Physiological endpoints in daphnid acute toxicity tests. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 700, 134400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiriacò, M.S.; Rizzato, S.; Primiceri, E.; Spagnolo, S.; Monteduro, A.G.; Ferrara, F.; Maruccio, G. Optimization of SAW and EIS sensors suitable for environmental particulate monitoring. Microelectron. Eng. 2018, 202, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzato, S.; Monteduro, A.G.; Buja, I.; Maruccio, C.; Sabella, E.; De Bellis, L.; Luvisi, A.; Maruccio, G. Optimization of SAW Sensors for Nanoplastics and Grapevine Virus Detection. Biosensors 2023, 13, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzato, S.; Leo, A.; Monteduro, A.G.; Chiriacò, M.S.; Primiceri, E.; Sirsi, F.; Milone, A.; Maruccio, G. Advances in the Development of Innovative Sensor Platforms for Field Analysis. Micromachines 2020, 11, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, C.; Sakarya, M.; Koh, O.; O’Donnell, M. Alterations in Hemolymph Ion Concentrations and pH in Adult Daphnia magna in Response to Elevations in Major Ion Concentrations in Freshwater. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2021, 40, 366–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 6341:2012; Water Quality—Determination of the Inhibition of the Mobility of Daphnia magna Straus (Cladocera, Crustacea)—Acute Toxicity Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012. Available online: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:6341:ed-4:v1:en (accessed on 1 December 2025).

- Ulm, L.; Vrzina, J.; Schiesl, V.; Puntaric, D.; Smit, Z. Sensitivity comparison of the conventional acute Daphnia magna immobilization test with the Daphtoxkit F™ microbiotest for household products. In New Microbiotests for Routine Toxicity Screening and Biomonitoring; Persoone, G., Janssen, C., De Coen, W., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 247–252. [Google Scholar]

- Persoone, G.; Baudo, R.; Cotman, M.; Blaise, C.; Thompson, K.C.; Moreira-Santos, M.; Vollat, B.; Törökne, A.; Han, T. Review on the acute Daphnia magna toxicity test—Evaluation of the sensitivity and the precision of assays performed with organisms from laboratory cultures or hatched from dormant eggs. Knowl. Managt. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2009, 393, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann, M.; Gutow, L.; Klages, M. Marine Anthropogenic Litter; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, R.; Kim, S.W.; An, Y.-J. Polystyrene nanoplastics inhibit reproduction and induce abnormal embryonic development in the freshwater crustacean Daphnia galeata. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 12095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, F.; Zhao, N.; Yin, G.; Wang, T.; Jv, X.; Han, S.; An, L. Rapid Response of Daphnia magna Motor Behavior to Mercury Chloride Toxicity Based on Target Tracking. Toxics 2024, 12, 621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bownik, A. Daphnia swimming behaviour as a biomarker in toxicity assessment: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 601–602, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovern, S.B.; Strickler, J.R.; Klaper, R. Behavioral and physiological changes in Daphnia magna when exposed to nanoparticle suspensions (titanium dioxide, nano-C60, and C60HxC70Hx). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 4465–4470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeong, T.Y.; Kim, H.Y.; Kim, S.D. Multi-generational effects of propranolol on Daphnia magna at different environmental concentrations. Environ. Pollut. 2015, 206, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A.K.; Wann, K.T.; Matthews, S.B. Lactose causes heart arrhythmia in the water flea Daphnia pulex. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004, 139, 225–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, B.; Sabatini, V.; Antenucci, S.; Gattoni, G.; Santo, N.; Bacchetta, R.; Ortenzi, M.A.; Parolini, M. Polystyrene microplastics ingestion induced behavioral effects to the cladoceran Daphnia magna. Chemosphere 2019, 231, 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Keefe, T.; Brewer, M.; Dodson, S. Swimming behavior of Daphnia: Its role in determining predation risk. J. Plankton Res. 1998, 20, 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.K.; Pirow, R. Physiological responses of Daphnia pulex to acid stress. BMC Physiol. 2009, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lett, Z.; Hall, A.; Skidmore, S.; Alves, N.J. Environmental microplastic and nanoplastic: Exposure routes and effects on coagulation and the cardiovascular system. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 291, 118190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres-Ruiz, M.; De la Vieja, A.; de Alba Gonzalez, M.; Esteban Lopez, M.; Castaño Calvo, A.; Cañas Portilla, A.I. Toxicity of nanoplastics for zebrafish embryos, what we know and where to go next. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 797, 149125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Duan, X.; Zhao, S.; Wang, X.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Peng, Y.; Gong, Z.; Wang, L. Barrier function of zebrafish embryonic chorions against microplastics and nanoplastics and its impact on embryo development. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 395, 122621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miragoli, M.; Novak, P.; Ruenraroengsak, P.; Shevchuk, A.I.; Korchev, Y.E.; Lab, M.J.; Tetley, T.D.; Gorelik, J. Functional interaction between charged nanoparticles and cardiac tissue: A new paradigm for cardiac arrhythmia? Nanomed 2013, 8, 725–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stampfl, A.; Maier, M.; Radykewicz, R.; Reitmeir, P.; Göttlicher, M.; Niessner, R. Langendorff heart: A model system to study cardiovascular effects of engineered nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 5345–5353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Häder, D.-P.; Erzinger, G.S. Daphniatox—Online monitoring of aquatic pollution and toxic substances. Chemosphere 2017, 167, 228–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simão, F.C.P.; Martínez-Jerónimo, F.; Blasco, V.; Moreno, F.; Porta, J.M.; Pestana, J.L.T.; Soares, A.M.V.M.; Raldúa, D.; Barata, C. Using a new high-throughput video-tracking platform to assess behavioural changes in Daphnia magna exposed to neuro-active drugs. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 662, 160–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brausch, K.A.; Anderson, T.A.; Smith, P.N.; Maul, J.D. The effect of fullerenes and functionalized fullerenes on Daphnia magna phototaxis and swimming behavior. Environ. Toxicol Chem. 2011, 30, 878–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noss, C.; Dabrunz, A.; Rosenfeldt, R.R.; Lorke, A.; Schulz, R. Three-dimensional analysis of the swimming behavior of Daphnia magna exposed to nanosized titanium dioxide. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.M.; Maul, J.D.; Saed, M.; Shah, S.A.; Green, M.J.; Cañas-Carrell, J.E. Bioaccumulation, stress, and swimming impairment in Daphnia magna exposed to multiwalled carbon nanotubes, graphene, and graphene oxide. Environ. Toxicol Chem. 2017, 36, 2199–2204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artells, E.; Issartel, J.; Auffan, M.; Borschneck, D.; Thill, A.; Tella, M.; Brousset, L.; Rose, J.; Bottero, J.-Y.; Thiéry, A. Exposure to Cerium Dioxide Nanoparticles Differently Affect Swimming Performance and Survival in Two Daphnid Species. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e71260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaiser, B.K.; Biswas, A.; Rosenkranz, P.; Jepson, M.A.; Lead, J.R.; Stone, V.; Tyler, C.R.; Fernandes, T.F. Effects of silver and cerium dioxide micro- and nano-sized particles on Daphnia magna. J. Environ. Monit. 2011, 13, 1227–1235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bownik, A.; Pawłocik, M.; Sokołowska, N. Effects of neonicotinoid insecticide acetamiprid on swimming velocity, heart rate and thoracic limb movement of Daphnia magna. Pol. J. Nat. Sci. 2017, 32, 481–493. [Google Scholar]

- Bownik, A.; Ślaska, B.; Dudka, J. Cisplatin affects locomotor activity and physiological endpoints of Daphnia magna. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bedrossiantz, J.; Faria, M.; Prats, E.; Barata, C.; Cachot, J.; Raldúa, D. Heart rate and behavioral responses in three phylogenetically distant aquatic model organisms exposed to environmental concentrations of carbaryl and fenitrothion. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 865, 161268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Rizzato, S.; Giacovelli, A.; Polo, G.; Sirsi, F.; Monteduro, A.G.; Udayan, G.; Ejaz, M.A.; Maruccio, G.; Lionetto, M.G. Integrated Analysis of Behavioral and Physiological Effects of Nano-Sized Carboxylated Polystyrene Particles on Daphnia magna Neonates and Adults: A Video Tracking-Based Improvement of Acute Toxicity Assay. Biosensors 2026, 16, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010010

Rizzato S, Giacovelli A, Polo G, Sirsi F, Monteduro AG, Udayan G, Ejaz MA, Maruccio G, Lionetto MG. Integrated Analysis of Behavioral and Physiological Effects of Nano-Sized Carboxylated Polystyrene Particles on Daphnia magna Neonates and Adults: A Video Tracking-Based Improvement of Acute Toxicity Assay. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010010

Chicago/Turabian StyleRizzato, Silvia, Antonella Giacovelli, Gregorio Polo, Fausto Sirsi, Anna Grazia Monteduro, Gayatri Udayan, Muhammad Ahsan Ejaz, Giuseppe Maruccio, and Maria Giulia Lionetto. 2026. "Integrated Analysis of Behavioral and Physiological Effects of Nano-Sized Carboxylated Polystyrene Particles on Daphnia magna Neonates and Adults: A Video Tracking-Based Improvement of Acute Toxicity Assay" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010010

APA StyleRizzato, S., Giacovelli, A., Polo, G., Sirsi, F., Monteduro, A. G., Udayan, G., Ejaz, M. A., Maruccio, G., & Lionetto, M. G. (2026). Integrated Analysis of Behavioral and Physiological Effects of Nano-Sized Carboxylated Polystyrene Particles on Daphnia magna Neonates and Adults: A Video Tracking-Based Improvement of Acute Toxicity Assay. Biosensors, 16(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010010