Noise Sources and Strategies for Signal Quality Improvement in Biological Imaging: A Review Focused on Calcium and Cell Membrane Voltage Imaging

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fluorescent Indicators for Membrane Voltage and Calcium Imaging

- –

- Voltage sensitive dyes (VSDs) are small, lipophilic organic molecules that become fluorescent after partitioning into the plasma membrane and change their optical properties (typically fluorescence intensity and/or spectrum) in response to changes in membrane potential. VSDs are capable of reporting fast voltage fluctuations, exhibiting response times significantly below 1 ms (often in the tens to hundreds of microseconds range) [10,11]. This rapid response allows them to track neuronal and cardiac action potentials without substantial temporal distortion. At the same time, classical synthetic VSDs have important limitations: they lack intrinsic cell-type specificity and stain essentially all accessible membranes; their high lipophilicity, which is necessary for efficient membrane incorporation, promotes nonspecific binding, can perturb membrane biophysics, and it increases toxicity at the concentrations required for functional imaging. For in vivo applications, an additional practical drawback is the challenge of delivering these hydrophobic dyes selectively and reproducibly to the target region, e.g., a defined brain area [12].

- –

- Calcium sensitive dyes (CSDs) are synthetic small molecules that localize to the cytosol or specific organelles and change their fluorescence intensity or spectrum upon binding Ca2+. They report the spatiotemporal profile of intracellular Ca2+, which is shaped by Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated channels, Ca2+ release and uptake by internal stores, buffering, and extrusion mechanisms [13,14]. Because membrane depolarization triggers Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated calcium channels, calcium transients often follow voltage changes, so CSD fluorescence can serve as an indirect optical readout of electrical activity [15]. However, it should be noted that CSD fluorescence reflects the integrated outcome of multiple Ca2+-handling processes rather than voltage dynamics alone. In addition, intracellular calcium transients are generally slower and more prolonged than the underlying membrane voltage changes, so calcium-sensitive dyes behave as low-pass filters that tend to integrate and underestimate rapid spike trains, especially at high firing rates. This temporal integration is particularly evident for somatic Ca2+ signals, although appropriately chosen low-affinity, fast indicators can still resolve individual action potentials and many fast synaptic Ca2+ transients on the millisecond–tens of milliseconds timescale [16,17,18]. Moreover, small or purely subthreshold depolarizations often produce little or no detectable change in bulk cytosolic Ca2+, making calcium dyes insensitive to subthreshold voltage activity.

- –

- Genetically encoded voltage indicators (GEVIs) and genetically encoded calcium indicators (GECIs) are fluorescent protein-based reporters designed to convert changes in membrane voltage or intracellular Ca2+, respectively, into changes in fluorescence. A key advantage of these probes is genetic targetability: by using cell type-specific promoters, they can be selectively expressed in defined cell populations or directed to specific subcellular compartments, enabling optical readouts of voltage or Ca2+ dynamics in chosen cells or organelles. Furthermore, both GEVIs and GECIs hold the potential for long-term multicellular recording, providing a means to observe the activity of complex cellular circuits over extended periods [19].

2.1. Performance Metrics for Voltage and Calcium Indicators

- –

- Sensitivity is defined as the magnitude of the indicator’s fluorescence change relative to the change in the measured parameter (e.g., calcium concentration or voltage). A highly sensitive indicator yields a substantial fluorescence response even to minor changes in the target parameter. For voltage indicators, sensitivity is often quantified as the relative change in fluorescence () produced by a defined voltage step, commonly 100 mV (for example, from −70 mV to +30 mV). In addition to the magnitude of , an equally important parameter is the voltage at which the midpoint of the fluorescence–voltage F(V) curve lies. This midpoint determines the voltage range over which the indicator operates in its steep, approximately linear regime. Consequently, optimal probe selection requires matching both the maximal and the F(V) midpoint to the expected membrane potential range of the preparation so that the sensor provides a high signal-to-noise ratio over the voltages of interest rather than saturating or operating on the shallow tails of its response curve. For calcium indicators, sensitivity is determined by the change in fluorescence intensity produced by a given fluctuation in Ca2+ concentration, for example, which is generated by a single action potential. The calcium dissociation constant () sets the concentration range over which an indicator is most responsive [44]. Because the fluorescence–[Ca2+] relationship is steepest near , indicators with low values are most sensitive to small changes around resting cytosolic Ca2+, whereas higher- indicators respond more linearly to large transients without saturation [45]. At the same time, Ca2+ affinity strongly influences signal-to-noise and kinetics: low-affinity indicators tend to produce faster signals but with smaller amplitude [18], while high-affinity indicators typically yield larger and better signal-to-noise ratios at the cost of more prolonged, integrative responses [46]. Therefore, the optimal CSD or GECI is chosen by balancing the affinity, dynamic range, and temporal resolution for the specific experimental task.

- –

- Brightness quantifies the strength of the fluorescence signal generated by the indicator. It is determined by two main factors: the dye’s efficiency in absorbing photons, quantified by its molar extinction coefficient () typically measured at the excitation peak, and its efficiency in emitting photons, which is quantified by the fluorescence quantum yield (FQY)–the ratio of emitted to absorbed photons across the entire emission spectrum. The fluorescence intensity per molecule, serving as the most informative metric for comparing the signal strength of similar indicators, is directly proportional to the product of and FQY [47]. In voltage and calcium imaging, higher molecular brightness improves the signal-to-noise ratio at a given excitation power, enabling a more reliable detection of small and fast transients. Brighter indicators can also be used with lower illumination intensity, thereby reducing phototoxicity and photobleaching while maintaining the desired measurement quality.

- –

- Photostability is the capacity of a fluorophore to withstand repeated excitation–emission cycles without a significant loss of signal over time. It is a critical parameter because photobleaching – the irreversible destruction of fluorophores under illumination—can severely limit the duration and reliability of imaging experiments. Although comprehensive, objective comparisons of photostability across indicators are still limited, newer generations of fluorophores are often specifically engineered to surpass the photostability of their predecessors. In voltage and calcium imaging, higher photostability allows longer recordings, more repeated trials, and stronger illumination (if needed) without rapid signal decay, thereby improving data quality and enabling a stable monitoring of fast or sparse events over extended time scales.

2.2. Qualitative and Quantitative Types of Measurement

- –

- Qualitative voltage and calcium measurements track relative changes in the fluorescence signal, rather than calibrated physical units, to report cellular activity. In these experiments, the readout is typically the change in fluorescence intensity normalized by a baseline or mean signal (), which reveals when and where neurons or other types of cells are active and how patterns of activity propagate, but it does not directly yield values such as millivolts or absolute calcium concentration. Because intensiometric measurements depend on variations in factors such as expression level (for GEVIs and GECIs), dye loading (for VSDs and CSDs), illumination power, and photobleaching, qualitative measurements accept these variables as uncontrolled and focus instead on comparing relative signals across time, stimuli, or conditions within the same preparation [47].

- –

- Quantitative measurements with ratiometric voltage and calcium sensors aim to estimate actual changes in membrane potential or Ca2+ concentration rather than just relative signal changes. Ratiometric probes operate by simultaneously measuring two distinct fluorescence signals that exhibit counter-directional changes in response to variations in voltage or Ca2+ [47]. The fundamental advantage of this approach is that dividing one signal by the other effectively cancels out common confounding factors, such as variations in the indicator concentration, illumination power, or modest sample movement. Achieving true quantitative results requires an additional step of careful calibration. For voltage indicators, this typically involves simultaneous electrophysiological recordings, often using patch-clamp techniques, to correlate the fluorescence ratio with membrane potential [7]. For calcium indicators, calibration can be achieved by determining the indicator’s dissociation constant () or by performing in situ titrations [47]. Once calibrated, the fluorescence ratio can be accurately mapped onto physical units, such as millivolts or Ca2+ concentration. This rigorous approach enables more accurate and reproducible quantification, facilitating robust comparisons across different cells, experimental preparations, and studies.

2.3. Classification of Voltage and Calcium Indicators

- –

- Voltage-sensitive dyes

- –

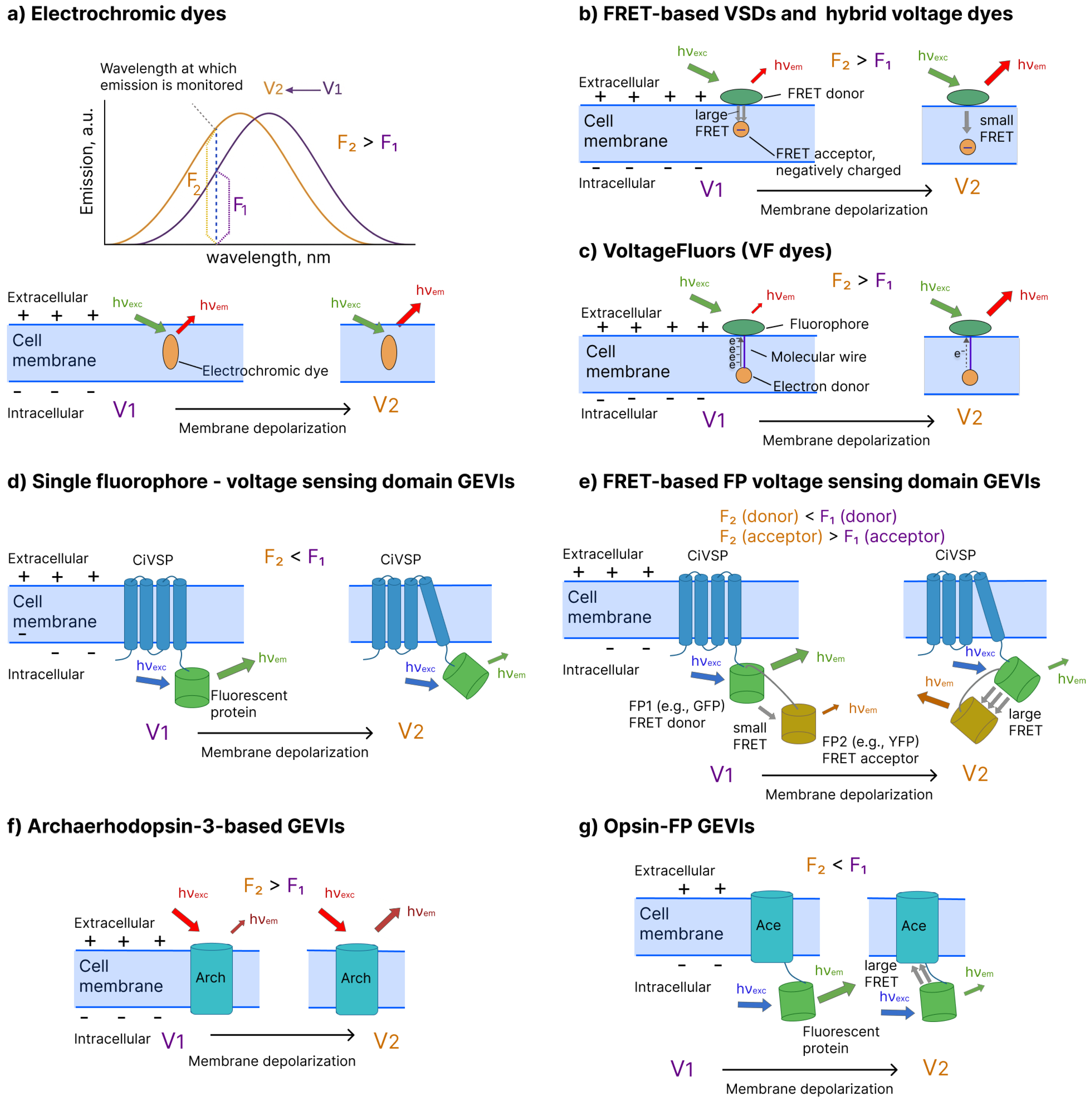

- Electrochromic VSDs(e.g., di-4-ANNEPS [20], CytoVolt1 [48], ANNIE-6plus [24]) are amphiphilic small molecules that partition into the plasma membrane and sense voltage through electrochromism, i.e., a rapid, linear electric-field-dependent shift in their absorption and/or emission spectra [10,11,49,50]. Both of these effects can be utilized for membrane voltage imaging. For dyes exhibiting a voltage-dependent shift of the fluorescence band, the detection wavelength is chosen on a steep (rising or falling) flank of the emission spectrum, such that even a small voltage-induced spectral displacement redistributes emission power relative to the detection window and yields a detectable increase or decrease in the measured fluorescence intensity (Figure 1a). Dyes exhibiting a voltage-dependent shift of the absorption band operate analogously but at the excitation step rather than emission. In this case, the excitation wavelength is chosen on a steep flank of the absorption spectrum so that spectral displacement alters the spectral overlap between the excitation band and the dye’s absorption band. The voltage-dependent shift therefore changes the fraction of incident photons that are absorbed and promoted to the excited state, producing a corresponding increase or decrease in the measured fluorescence intensity.A key advantage of electrochromic VSDs is that they can support ratiometric measurements: two fluorescence signals are recorded at two fixed wavelengths and positioned on opposite sides of the emission band so that the voltage-induced shift of the spectrum causes counter-directional changes: and . Taking the ratio yields a signal that depends on membrane potential (, where ) but is largely independent of dye concentration, illumination intensity, or photobleaching, because any global scaling factor (for example, dye loss from to ) multiplies both the numerator and denominator and thus cancels out in the ratio. This ratiometric approach reduces artifacts from dye leakage, nonuniform staining, and slow signal drifts, providing a more robust and quantitative readout of membrane voltage than single-channel intensity measurements.

- –

- FRET-based VSDs(e.g., DiO/DPA [51], CC2-DMPE/DiSBAC4(3) [52]) exploit Forster resonance energy transfer, whose efficiency depends steeply on the distance and relative orientation between donor and acceptor fluorophores [53]. In classical implementations, the donor is an immobile, membrane-associated fluorophore, whereas the acceptor is a mobile, negatively charged lipophilic dye (typically an oxonol) that redistributes within the electric field across the membrane. Changes in membrane potential drive the oxonol to move closer to or farther from the donor layer, thereby modulating the donor–acceptor separation and FRET efficiency, which in turn alters both donor quenching and acceptor emission (Figure 1b). As with electrochromic dyes, these probes enable a ratiometric readout by monitoring the ratio of donor and acceptor fluorescence, providing the usual advantages of ratiometry, including reduced sensitivity to variations in dye concentration or illumination intensity.

- –

- Hybrid voltage sensors(hVOS, e.g., hVOS 2.0 [54,55]) use the same FRET principle as small-molecule FRET VSDs but combine a genetically encoded fluorescent protein with a synthetic, voltage-sensing quencher. In most hVOS designs, a membrane-anchored fluorescent protein (e.g., eGFP or other XFPs) acts as the FRET donor, while the negatively charged, lipophilic anion dipicrylamine (DPA) serves as a non-fluorescent acceptor whose membrane distribution depends on the voltage. Changes in membrane potential drive DPA to shuttle between the inner and outer leaflets of the lipid bilayer, thereby changing its distance to the membrane-anchored fluorescent protein and modulating FRET efficiency, which results in voltage-dependent quenching of the donor fluorescence. A key advantage of this chemigenetic architecture is that the spectral properties are largely defined by the choice of fluorescent protein, so hVOS probes can, in principle, be engineered across different spectral ranges, enabling the flexible selection of excitation and emission wavelengths and easier multiplexing with other optical indicators or actuators.

- –

- VoltageFluors(VF dyes, e.g., FluoVolt [25,56], BeRST1 [26]) report changes in membrane potential by modulating the rate of photoinduced electron transfer (PeT) between an electron-rich or electron-poor moiety and a fluorescent reporter embedded in the plasma membrane (Figure 1c). In a typical design, the dye consists of a bright fluorophore linked via a conjugated molecular wire (often phenylenevinylene- or fluorene-based) that spans the membrane to an electron donor (for donor-PeT) or acceptor (for acceptor-PeT). In the resting state, PeT from the donor to the excited fluorophore (or from the excited fluorophore to an acceptor) partially quenches fluorescence. Changes in membrane potential alter the local electric field across the membrane, shifting the PeT efficiency and thereby changing the fluorophore’s quantum yield and fluorescence intensity. VF dyes therefore convert voltage-dependent changes in the PeT efficiency into large, approximately linear changes in fluorescence (often 20–50% per 100 mV) with submillisecond kinetics, enabling an accurate optical recording of action potentials and fast subthreshold voltage dynamics in neurons and other excitable cells [49].

- –

- Genetically Encoded Voltage Indicators

- –

- Single-fluorophore voltage-sensing domain GEVIs (e.g., ArchLight A242 [30], ASAP5 [28], JEDI-1P [57]) constitute a major class of genetically encoded voltage indicators in which a transmembrane voltage sensing domain is directly fused to a fluorescent protein (FP) (Figure 1d). Voltage-dependent conformational rearrangements of the domain are allosterically coupled to changes in FP fluorescence [2]. These constructs most commonly employ the Ciona intestinalis voltage-sensing phosphatase (Ci-VSP) as the voltage-sensing module with an FP engineered to report subtle alterations in the chromophore environment. Most members of this family, e.g., ArcLight [30] or ASAP5 [28], exhibit negative-going responses in which membrane depolarization produces a reduction in fluorescence intensity. Some other indicators, such as Marina [58] and FlicR1 [59], display positive-going responses, where depolarization leads to an increase in fluorescence.

- –

- FRET-based fluorescent protein (FP) voltage-sensing domain GEVIs (e.g., Mermaid2 [60], VSFP-Butterfly [61]) typically employ a single voltage-sensing domain fused to a donor–acceptor FP pair (intramolecular FRET design, as shown in Figure 1e) [2]. Voltage-dependent conformational rearrangements of the domain alter the relative distance and/or orientation of the two FPs, modulating the efficiency of FRET and producing counter-directional changes in donor and acceptor fluorescence. More recently, intermolecular FRET-based GEVIs have extended this concept by placing donor and acceptor FPs on separate voltage-sensing domains [62]. This spatial arrangement allows voltage-driven conformational changes of these multiple domains to collectively alter the average donor–acceptor separation and orientation within the membrane. FRET-based GEVIs support ratiometric readout (acceptor/donor or donor/acceptor), which suppresses common noise sources such as excitation intensity fluctuations, nonuniform expression, or sample motion at the cost of increased construct size and optical complexity (two excitation/emission channels are required).

- –

- Microbial opsin-based GEVIs harness the voltage-sensing capabilities of several microbial rhodopsins. These proteins exhibit voltage-dependent changes in their absorption or emission spectra [63]. Specifically, some microbial rhodopsins (e.g., Acetabularia rhodopsin [64], L. maculans rhodopsin [64]) demonstrate a large shift of the absorption band upon membrane depolarization. In turn, in archaerhodopsin-3 and its mutants, membrane depolarization leads to an increase in fluorescence intensity. These two remarkable effects are exploited in two existing classes of microbial opsin-based GEVIs.Archaerhodopsin-3-based sensors (e.g., QuasAr6a [65], Archon1 [32]) are derived from archaerhodopsin-3 (Arch), which is a microbial rhodopsin with intrinsically voltage-dependent near-infrared fluorescence that increases with membrane depolarization (Figure 1f). Although wild-type Arch is extremely dim [66], the insertion of amino acid replacements have produced much brighter probes [67]. Prominent examples include representatives from the three families: Archers [68,69,70], QuasArs [31,65], and Archons [32]. These rhodopsin-only GEVIs exhibit large fractional fluorescence changes per 100 mV, submillisecond response kinetics, and high photostability. However, these indicators remain substantially dimmer than FP-based GEVIs [67,71], often requiring stronger excitation and/or more sensitive detectors to achieve an adequate signal-to-noise ratio. In addition, they are also inefficiently excited under two-photon illumination, which limits their utility for deep in vivo imaging compared with many FP-based indicators [72].Opsin–FP eFRET GEVIs (e.g., VARNAM [73], Ace2N-mNeon [74]) fuse a bright fluorescent protein to a voltage-sensitive microbial rhodopsin whose absorption spectrum shifts with membrane potential (Figure 1g). At negative (resting) membrane voltages in the classical, negative-going designs, the rhodopsin absorbance is significantly blue-shifted from the FP emission, so the FRET is weak and the FP remains bright. Upon membrane depolarization, the rhodopsin absorption band red-shifts and effectively overlaps the FP emission band, enhancing FRET and producing a decrease in FP fluorescence; these indicators therefore report depolarization as a negative-going signal. Recent engineering has inverted this relationship, producing opsin-FP GEVIs (e.g., Positron [75], pAce [34]) with lower fluorescence at rest and positive-going fluorescence changes on depolarization while preserving sensitivity and kinetics. This architecture retains the high brightness advantage of FP-based reporters, as well as the fast kinetics of rhodopsin-based reporters, but it typically sacrifices some of the advantages of the rhodopsin-only sensors, such as high photostability.

- –

- Bioluminescent GEVIs are a unique class of genetically encoded voltage indicators in which light is produced enzymatically by a luciferase–luciferin reaction, eliminating the need for external optical excitation [76,77]. In bioluminescent FRET-type GEVIs, a luciferase (donor) and a fluorescent protein (acceptor) are fused to a single transmembrane voltage-sensing domain. Voltage-dependent conformational changes in the domain modulate the distance and relative orientation of the two proteins, thereby changing bioluminescence resonance energy transfer (BRET) efficiency and donor/acceptor emission intensity. A significant benefit of these sensors is that they do not require external excitation light, thereby eliminating any excitation-dependent background and many phototoxicity concerns. Moreover, because bioluminescent voltage reporters can exhibit very low baseline emission at rest, voltage transients can generate bursts of photons against an almost dark background, offering the potential for superior sensitivity in voltage imaging. However, bioluminescent emission is much dimmer than fluorescence from bright FPs, which typically necessitates highly sensitive cameras and/or longer integration times. An additional practical disadvantage is the requirement to supply an exogenous luciferin substrate to the tissue or organism, complicating delivery and potentially limiting experimental duration as substrate is consumed.

- –

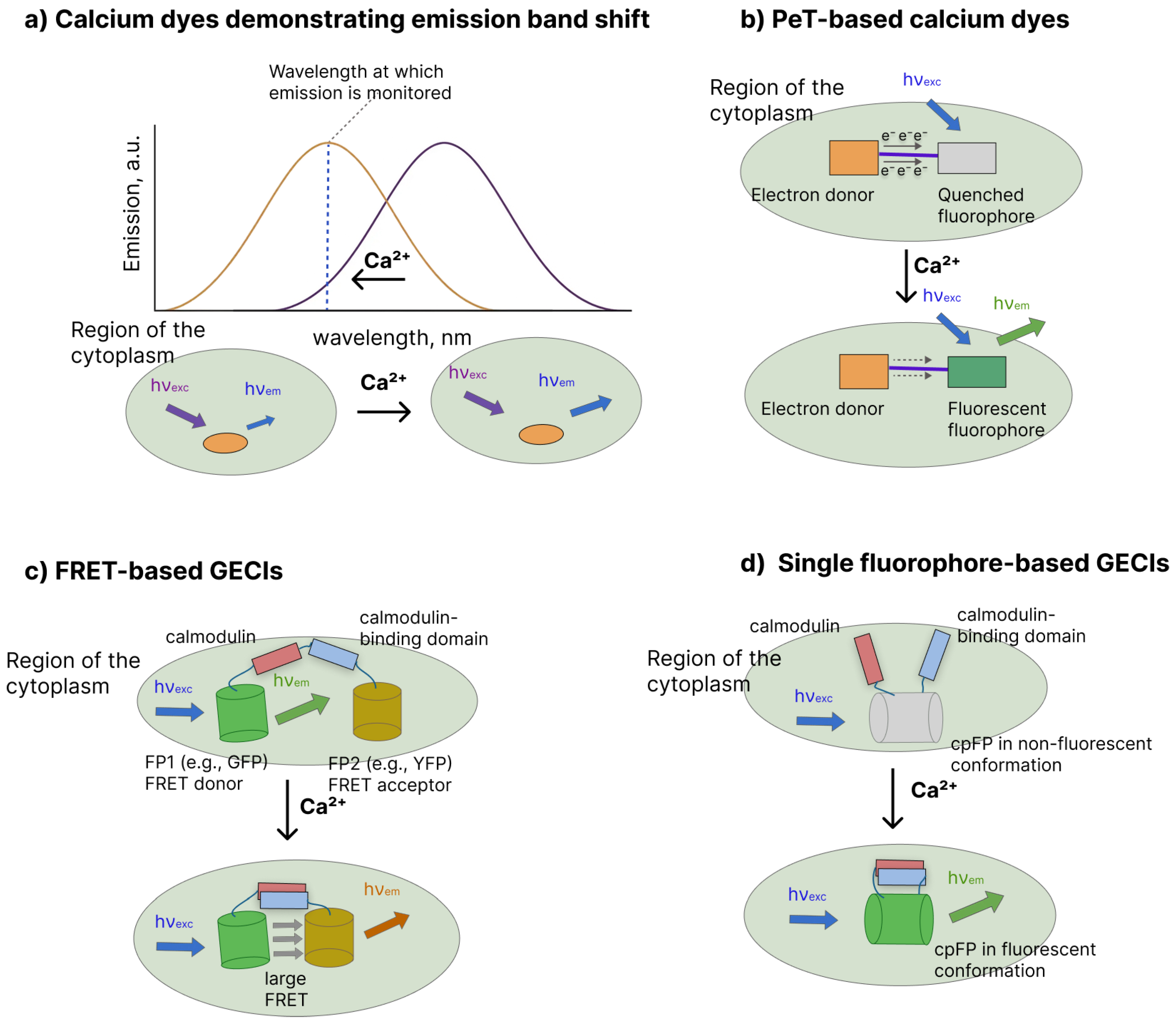

- Calcium-sensitive dyes (CSDs) are small-molecule fluorescent indicators that couple a Ca2+-chelating moiety to an organic fluorophore. They are commonly grouped into ratiometric indicators, which exhibit Ca2+-dependent spectral shifts, and “single-wavelength” intensiometric indicators, which show Ca2+-dependent changes in fluorescence intensity [15,78].

- –

- Ratiometric Ca2+ dyes (e.g., Fura-2 [79] and Indo-1 [79]) display Ca2+-induced shifts in excitation (Fura-2) or emission (Indo-1) spectra, enabling ratiometric imaging that corrects for variations in dye concentration or light intensity in a manner analogous to the ratiometric use of electrochromic VSDs (Figure 2a) [15,80]. For example, there is the maximum emission of Indo-1 shifts from 475 nm in the ion-free state to approximately 400 nm when saturated with Ca2+, providing a robust ratiometric readout [81].

- –

- Non-ratiometric (intensiometric) indicators(e.g., Fluo-3 [82], Cal-520 [83], Oregon Green BAPTA dyes [46]) rely mainly on a Ca2+-induced increase in fluorescence quantum yield mediated by intramolecular photoinduced electron transfer (Figure 2b). In the Ca2+-free state, the electron-rich chelator is close to the fluorophore and efficiently quenches its excited state through PeT, keeping the dye weakly fluorescent; Ca2+-binding reorganizes the chelator and decreases its electron-donating ability, suppressing PeT and producing a large turn-on in fluorescence intensity.

- –

- Genetically Encoded Calcium Indicators. Many widely used GECIs are built around calmodulin (CaM), which is a soluble Ca2+-binding protein found in nearly all cells. In many early and current designs, CaM is paired with a CaM-binding peptide derived from myosin light-chain kinase, although other CaM-binding sequences are also used [84,85]. In the Ca2+-free state, CaM and the peptide interact only weakly; Ca2+ binding to CaM induces a large conformational change that promotes the tight association between CaM and the peptide, which is then transduced into an optical signal by one or two attached fluorescent proteins. As a reporter, this architecture is implemented either with a FRET donor–acceptor pair (FRET-based GECIs) or with a single fluorescent protein (single-fluorophore GECIs).

- –

- FRET-based GECIs (e.g., cameleons [86] and YC-nano indicators [87]) place a donor fluorescent protein on CaM and an acceptor fluorescent protein on the CaM-binding peptide, forming a FP–CaM–linker–peptide–FP fusion (Figure 2c). Under low Ca2+, CaM and the peptide are relatively separated, resulting in low FRET efficiency and a signal dominated by donor emission when the donor is selectively excited. Ca2+ binding to CaM triggers CaM–peptide association, shortening the donor–acceptor distance, which increases FRET and is recorded as an increase in acceptor emission relative to donor emission (i.e., a ratiometric change).

- –

- In single-fluorophore GECIs (e.g., GCaMP [41,88,89,90], GECO [91,92], and jGCaMP/ jRGECO [93] families), CaM and a CaM-binding peptide are integrated into the fluorescent protein scaffold (Figure 2d). In most designs, they are fused to the termini of a circularly permuted fluorescent protein (typically cpEGFP or related variants) [94,95] or inserted into an internal loop of the FP [96,97]. In the Ca2+-free state, the local structure around the chromophore is configured to favor nonradiative decay and weak fluorescence, whereas Ca2+ binding drives CaM–peptide association, reorganizes the chromophore microenvironment, and produces a large increase in fluorescence intensity.

3. Signal Quality in Voltage and Calcium Imaging: Determinants and Refinement

- –

- Systematic deviations (systematic offset, bias): A consistent, predictable offset from the true value that remains stable across measurements taken under the same conditions (e.g., a camera systematic offset or an autofluorescence background signal). This measurement error can be evaluated through preliminary experiments and subsequently calibrated out via subtraction or division. It is convenient to categorize systematic deviations in biological imaging as either device-related (instrumental bias) or sample-related (biological or preparation bias).

- –

- Stochastic deviations (noise): Random fluctuations around the true value (e.g., photon shot noise, or dark noise). Noise can be classified into three primary types: fundamental photon shot noise, stemming from the quantum nature of photons; device-related noise, caused by instability in equipment like light sources or camera electronic components; and sample-related noise, which is linked to sample preparation and intrinsic sensor properties. Quantitatively, the noise of each origin can be characterized by the standard deviation () or signal variance (). Given the independence of all noise sources, the overall signal variance () equals the sum of the variances produced b y each noise component. The SNR is defined as the ratio of the mean signal magnitude () to the standard deviation of the total noise ():

4. Photon Shot Noise and Shot-Noise Limited Regime

- –

- Light sources: A direct way to increase the photon flux coming to the camera detector is to increase the intensity of the excitation light. However, this solution should be applied accurately to prevent phototoxicity or the acceleration of fluorophore photobleaching.

- –

- Exposure time: For a constant photon flux, a longer exposure time leads to a proportionally larger number of accumulated photons per frame, while the signal-to-shot-noise ratio improves in proportion to the square root of the exposure time [103]. However, this solution comes at the cost of decreased temporal resolution, which is often critical for recording fast biological processes.

- –

- Objective lens: The objective lens is arguably the most critical optical component determining the efficiency of photon collection and, consequently, the achievable SNR for the photon shot noise limit. The numerical aperture (NA), defined as (where n is the refractive index of the immersion medium and is the half-angle of the maximum cone of light captured by the lens), directly dictates the magnitude of the collected signal. A higher NA lens gathers light from a significantly wider angle, thus capturing a greater number of signal photons within a given exposure time [66,99,104].

- –

- Optical filters and dichroic mirrors: Optical filters and dichroic mirrors are essential optical components that significantly impact the SNR for the photon shot noise limit by governing light throughput and background rejection. The use of high-quality excitation and emission filters with high transmission percentages (e.g., >95% transmission) ensures the efficient passage of signal photons through the optical path. Maximizing the transmission of the desired signal while minimizing unwanted background light improves the effective SNR. This prioritization ensures the captured light accurately represents the true biological event, enabling the system to operate closer to the theoretical, shot-noise limited regime where data quality is maximized.

- –

- Confocal pinhole: Enlarging the area from which photons are collected, e.g., by increasing the pinhole size of the confocal microscope [105], also yields a larger number of photons per frame but comes at the cost of decreased spatial resolution and an increased interference of background signal collected from out-of-focus regions.

- –

- Quantum efficiency of the camera: Quantum efficiency (QE) is defined as the percentage of incident photons that a camera sensor successfully converts into a measurable electrical charge. QE is not a single number but a curve that is wavelength-dependent. Cameras are often optimized for the green/yellow spectrum (500–600 nm), which is common for many popular fluorophores. QE typically drops in the UV and far-red/NIR regions. This value is a critical determinant of the camera’s sensitivity and the achievable SNR. In modern cameras, the QE varies from 80% to >95%. A higher QE is always beneficial for SNR enhancement provided all other factors of the experimental setup remain constant, and the trade-off is primarily a higher price of high-QE cameras, particularly those using back-illuminated sensors.

- –

- Pixel size: Larger pixels of a sensor collect more photons during the same exposure time as smaller pixels, assuming a consistent density of incident light. The obvious trade-off, however, is a reduction in spatial resolution.

- –

- Signal averaging (temporal and spatial). A powerful general strategy is to perform signal averaging, which increases the SNR proportionally to the square root of the number of accumulated measurements. This approach can be implemented in several ways.When periodic events are analyzed, temporal averaging can be performed by aggregating data from repeated trials [12,74,106,107]. For non-repeating events, photon counts that originate from a specific pixel or region can be averaged across consecutive frames or time points [108,109,110].To perform spatial averaging, data from adjacent pixels are combined to mitigate random spatial fluctuations. Modern computational algorithms ensure that such an averaging is performed precisely within the region of interest by utilizing automatic segmentation to accurately define the boundaries and exclude pixels from non-target regions [111,112,113].

- –

- Frequency-domain approaches. Another class of denoising strategies is based on the frequency-domain distinction between the low-frequency part of the signal, which is due to biological events, and the high-frequency part of the signal, which is due to shot noise. Random fluctuations with frequencies above a predefined cutoff value can be suppressed using low-pass filters, such as Gaussian or Butterworth filters, which ensure that only the lower-frequency components of the signal pass [71,101]. In principle, the filter cutoff should be set just above the fastest frequency component of the signal that one wishes to preserve, in order to efficiently suppress high-frequency shot noise without distorting the underlying kinetics of the measured biological event. In practice, however, the choice of cutoff frequency should be guided by the experimental goal.

- –

- Dimensionality reduction methods. Finally, significant differences in the properties of signal and shot noise enable the application of dimensionality reduction algorithms, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) [114,115]. These methods process pixel intensity variations across a series of frames, extracting spatially and temporally coherent changes (the signal) while discarding small, dispersed fluctuations (the shot noise). Several more advanced versions of this method have also been developed, including those that apply deep learning-based approaches [116,117].

- –

- In calcium imaging, indicators are usually distributed throughout the cytosolic volume, so a substantial number of fluorophores contribute to the signal from each cell. In contrast, most voltage indicators are confined to the thin plasma membrane, meaning that far fewer molecules occupy the relevant optical volume. As a result, for comparable excitation conditions, substantially fewer photons are emitted and collected from a single cell in voltage imaging than in calcium imaging, which directly increases the relative contribution of photon shot noise.

- –

- Genetically encoded calcium indicators often exhibit large fractional fluorescence changes () during robust Ca2+ transients with some brightening GECIs exceeding 100% [41,90,118]. By comparison, many voltage indicators typically exhibit smaller fractional changes in their fluorescence upon corresponding voltage changes (e.g., action potentials) [28,119,120,121]. Importantly, alone does not determine practical sensitivity: a bright probe with modest can achieve a higher signal-to-noise ratio than a very dim probe with a large , because photon shot noise depends on the absolute photon count. This consideration is particularly relevant for archaerhodopsin-3-based GEVIs, which are substantially dimmer than most GECIs or fluorescent-protein-based GEVIs and therefore require higher excitation intensities or tolerate lower SNRs in order to resolve the same physiological events.

- –

- In many standard calcium-imaging experiments, fluorescence signals are large because the underlying Ca2+ transients can represent 5- to 10-fold increases in intracellular concentration in some compartments [122], and brightening GECIs convert these excursions into large responses. In contrast, the membrane potential changes that underlie voltage imaging typically span a narrower range: an action potential involves a change of about 100 mV (from roughly −70 mV to +30 mV), and many subthreshold events are only a few millivolts in amplitude [28]. Consequently, many commonly used voltage indicators are operated over a relatively small dynamic range in membrane potential and often exhibit more modest fractional fluorescence changes under typical conditions.

- –

- A further critical distinction between voltage and calcium imaging is the typical timescales and experimental regimes in which they are applied. Calcium imaging is often used to monitor comparatively slow cellular processes, such as somatic calcium signals associated with neuronal firing, which frequently evolve over hundreds of milliseconds to seconds in population-level recordings. At the same time, localized calcium events (e.g., synaptic or presynaptic transients) can exhibit rise times of only a few milliseconds and therefore may also require high-speed acquisition to be accurately resolved [123]. In contrast, voltage imaging is routinely employed to study much faster electrical phenomena, including individual action potentials and high-frequency spike trains, whose kinetics are inherently sub-millisecond. Reflecting these use cases, many large-scale calcium imaging experiments operate at frame rates on the order of 10–30 Hz [124], whereas direct voltage sensors are commonly used with acquisition rates in the kilohertz range to capture rapid voltage dynamics with sub-millisecond temporal resolution. Given these differences in effective kinetics and typical frame rates, strategies for mitigating photon shot noise necessarily diverge. In calcium imaging, relatively long exposure times can often be employed to accumulate a large number of photons per frame, improving the signal-to-shot-noise ratio without compromising temporal resolution in many applications. By contrast, voltage imaging experiments usually require exposure times of 1 ms or less to preserve the fast temporal structure of the signal, which drastically reduces the number of detected photons per frame and correspondingly amplifies the impact of photon shot noise [125,126].

5. Systematic and Stochastic Instrumental Measurement Errors

5.1. Dark Current, Dark Noise and Camera Systematic Offset

- –

- Cooling camera sensor: The primary method that can be employed is to cool the camera sensor [127,128,129]. The temperature decrease leads to lowering both the systematic offset (dark current) and dark noise. In typical research-grade neuronal calcium imaging experiments, the use of cooled cameras is standard practice. Neuronal calcium dynamics often involve capturing relatively subtle fluorescence signals over extended periods, making it critical to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) for accurate quantitative analysis. Voltage imaging faces even greater SNR challenges due to its faster kinetics (sub-millisecond resolution) and lower-sensitivity indicators. Integrated active cooling in scientific CCD, EM-CCD, and sCMOS cameras is commonly implemented with thermoelectric coolers that use the Peltier effect to extract heat from the sensor [130]. Such Peltier-based systems routinely cool detectors tens of degrees below ambient with typical operating temperatures in the range from 0 °C to −40 °C and −50 °C. In deep-cooled EM-CCD systems, multi-stage Peltier devices operating in a vacuum can reach temperatures of up to −80 °C. Achieving and maintaining these deep-cooled operating points requires the efficient removal of waste heat from the hot side of the TEC—typically via forced-air or liquid cooling and high-quality vacuum insulation. TECs integrated into scientific sCMOS and EM-CCD cameras significantly reduce the dark current and thermal noise. Typical silicon CCD and sCMOS sensors show an exponential decrease in dark current with temperature with the dark current roughly halving for every 5–7 °C of cooling in the range relevant for scientific imaging. For example, measurements on cooled CCDs report dark currents on the order of a few electrons per pixel per second near −20 °C, falling to ≲ at about −80 °C, implying a reduction by roughly two to three orders of magnitude. The associated dark noise decreases proportional to the square root. Therefore, adjusting the sensor cooling regime ensures stable experimental baselines and enables operation closer to the shot-noise limited regime, preventing even weak biological signals from being masked by camera noise and supporting quantitatively reliable, reproducible measurements over acquisition times of many minutes to hours.

- –

- –

- Camera sensors gain minimization (if possible): While gain does not directly prevent dark current generation, some EM-CCD gain processes can amplify the accumulated dark current noise, making careful gain application important.

5.2. Bias Offset and Read Noise

- i

- Photon detection and charge accumulation: The functional architecture of a CCD is built upon an array of metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) capacitors arranged in a grid, which define the individual pixels. When incident photons strike the silicon substrate, they generate electron–hole pairs via the photoelectric effect. The applied potentials within each pixel establish a localized potential well that effectively collects and stores the signal electrons. Crucially, the amount of accumulated charge is directly proportional to the incident light intensity, which is an inherent property known as photometric linearity. This phase concludes after a defined integration period, which is often termed the exposure time.

- ii

- Charge transfer (shift register operation): Following the integration period, the accumulated charge must be read out. The “coupled” aspect of the CCD design facilitates this essential transfer of charge. A synchronized, multi-phase clocking voltage sequence is applied to adjacent gates along the pixel array. This dynamic manipulation of potential wells effectively shifts the entire packet of accumulated charge, pixel by pixel, first down vertical shift registers and subsequently through a single horizontal shift register. This process occurs without significant loss of charge to maintain image fidelity (high charge transfer efficiency, or CTE).

- iii

- Signal readout and analog-to-digital (ADC) conversion: The sequenced charge packets are delivered one at a time to a specialized floating diffusion node, which serves as the output node. This node performs the crucial conversion of the discrete charge packet into a measurable analog voltage signal. An on-chip pre-amplifier then boosts this small voltage signal for subsequent processing. At this point in the signal chain, a fixed DC voltage known as the bias offset is also intentionally applied to the analog signal to ensure that all subsequent signal and noise values remain positive, thereby preventing negative noise fluctuations from being clipped to zero during analog-to-digital conversion. Within the same amplification and conditioning stage, the primary source of random electronic uncertainty, known as readout noise (read noise), arises. This noise originates mainly from two sources within the amplifier circuitry: thermal noise (or Johnson–Nyquist noise), which arises from the random thermal motion of electrons within the amplifier’s resistors and varies with temperature and bandwidth; and flicker noise (or noise), which is characterized by power that is inversely proportional to frequency and originates from imperfections in the semiconductor materials. Finally, an external or on-chip analog-to-digital converter (ADC) quantizes the amplified analog signal into discrete digital values, which represent the pixel brightness levels and collectively form the digital image file.

- –

- Front-Illuminated CCDs: Standard designs where light must pass through opaque wiring layers, resulting in lower QE of around 40–60%.

- –

- Back-Illuminated (biCCD): The silicon sensor is inverted, allowing light to enter directly from the rear, bypassing internal wiring and achieving high QE (up to 97%) and superior sensitivity for low-light applications.

- –

- Full-frame CCDs: These architectures utilize the entire sensor area for light collection, offering maximal light collection efficiency per unit area. They require the image data to be read out sequentially row by row from the photosensitive area. This slow process results in very low readout noise due to longer integration times, making them suitable for static or long-exposure imaging.

- –

- Interline-transfer/Frame-transfer CCDs: These designs are optimized for speed and continuous imaging by employing internal mechanisms for rapid charge relocation.

- –

- Interline-transfer models incorporate masked (light-shielded) vertical columns adjacent to every photosensitive pixel column. After a brief exposure, the charge from the illuminated pixels is rapidly shifted sideways into these shielded columns within microseconds. The next exposure can then begin immediately in the active area while the previously stored data are read out.

- –

- Frame-transfer models partition the sensor into two equal halves: an active imaging area and a light-shielded storage array. The entire image is shifted from the imaging area to the storage area in milliseconds. This allows the imaging array to start the subsequent exposure immediately, while the data are read out from the shielded storage array.

Both mechanisms enable fast electronic shuttering and readout rates suitable for live-cell imaging without motion blur or the need for a mechanical shutter. Faster readout speeds often correlate with slightly higher readout noise compared to full-frame CCDs. - –

- Electron-Multiplying CCDs (EM-CCDs): This functional variation incorporates an on-chip gain register that amplifies weak signals before they encounter the readout electronics. This electronic gain effectively masks the conventional readout noise floor, making it negligible (sub-electron). This unique capability provides several benefits: it enables true single-photon detection, facilitates high frame rates in photon-starved scenarios by allowing very short exposure times, and maximizes the signal-to-noise ratio even at the lowest light levels.

- –

- Front-Illuminated CMOS or sCMOS: Similar to CCDs, it is CMOS or sCMOS sensors with conventional designs that route light through opaque wiring layers, providing a low QE value of around 40–60%.

- –

- Back-Illuminated (bi-sCMOS): The sCMOS sensor is inverted in back-illuminated designs, allowing light to enter directly from the rear and bypass internal wiring. This architectural change achieves high quantum efficiency (QE) (up to 95%+) and superior sensitivity, which are essential for low-light biological imaging.

- –

- Scientific CMOS (sCMOS): To meet the rigorous demands of scientific research, sCMOS (scientific CMOS) technology was developed. The sCMOS dual-amplifier design is an architectural innovation that fundamentally solves the traditional trade-off between sensitivity and dynamic range. In conventional systems (including standard CCDs and CMOS), the user must select a single gain setting, forcing a compromise. Gain, in this context, refers to the electronic amplification factor applied to the signal voltage to increase sensitivity or accommodate brighter signals, which are typically measured as electrons per analog-to-digital unit (/ADU). Maximizing sensitivity requires high electronic gain to lift dim signals above the read noise floor, but high gain quickly causes bright signals to saturate the sensor, drastically limiting the dynamic range (defined as the ratio between the brightest non-saturating signal and the noise floor). Conversely, low gain accommodates bright signals but buries dim signals in the noise. The sCMOS architecture resolves this issue by capturing both scenarios simultaneously by employing specific design innovations, such as a dual-amplifier design within the column readout structure. This feature allows the sensor to simultaneously read a pixel’s charge through both a high-gain channel and a low-gain channel. These two independent channels function in a complementary manner: the high-gain amplifier channel is optimized for sensitivity and low noise detection, making it ideal for capturing weak fluorescence signals, while the low-gain (high-capacity) amplifier channel is optimized for a large charge capacity or full well depth, allowing it to accurately measure very bright signals without saturation. The data from these two channels are digitized independently and then combined in a sophisticated process executed by the camera’s internal firmware. This merging algorithm typically compares the raw data from both channels pixel by pixel. For pixels where the high-gain channel data are valid (i.e., not saturated), that low-noise value is selected. For pixels that saturated the high-gain channel, the data from the low-gain channel are used. A linear scaling factor is applied to match the values from both channels precisely, producing a single, seamless, high bit-depth image that optimally utilizes both the minimum noise floor and maximum well capacity simultaneously.

5.3. Light Source Fluctuations

- –

- Mercury arc lamps provide broad and intense spectral output with strong emission lines in the UV and visible range that are well suited for widefield fluorescence excitation. However, they exhibit characteristic drawbacks, including arc wander and plasma instabilities that cause flicker and short-term intensity fluctuations, as well as a progressive decrease in output as the lamp ages and the arc envelope degrades. These effects lead to poorer temporal stability and long-term reproducibility.

- –

- Xenon arc lamps exhibit a relatively smooth, quasi-continuous spectrum across the visible range and provide more uniform spectral brightness than mercury lamps, which are dominated by discrete emission lines. However, they still suffer from arc wander and plasma instabilities that produce measurable intensity fluctuations, require warm-up, and have a finite lamp lifetime on the order of a few hundred to roughly a thousand hours, leading to gradual output degradation over time.

- –

- Light-emitting diodes (LEDs) provide highly stable illumination, with low short-term intensity noise, modest heat generation at the sample plane, and fast, linear electronic modulation, which makes them well suited for time-resolved, quantitative, and ratiometric imaging. Their output is largely free of arc-related flicker seen in discharge lamps, although small long-term drifts can still occur due to temperature-dependent changes in LED junction characteristics and driver electronics, especially in inadequately cooled or unregulated systems [134].

- –

- Solid-state lasers provide very high temporal stability and spatial coherence, especially when combined with electronic current regulation and, in high-end systems, active power stabilization based on feedback from a reference photodiode. Their output consists of narrow spectral lines with minimal temporal variation, which makes them particularly well suited for confocal, multiphoton, and super-resolution modalities that require intense, precisely defined, and highly stable excitation beams.

5.4. Scanning System Noise

6. Sample-Related Measurement Errors

6.1. Tissue Scattering

6.2. Autofluorescence

6.3. Motion Artifacts

6.4. Photobleaching

6.5. Mistargeted Sensors

- –

- Standard deviation-based algorithms identify the functional region of interest through temporal variability by calculating the standard deviation of intensity over time for each pixel [66,202]. Pixels that fluctuate strongly are identified as active signal areas, while pixels with high fluorescence intensity but low temporal fluctuation are considered background and computationally excluded.

- –

- Pixel correlation algorithms represent another class of highly effective methods that utilize the fact that pixels belonging to the region of interest are highly correlated in time [203]. When the cell undergoes a voltage or calcium change, all pixels in that functional area rise and fall together coherently. Conversely, pixels containing only random noise or static background fluorescence are uncorrelated with this dynamic activity. Pixel correlation algorithms calculate the temporal cross-correlation coefficient between pixel traces; then, correlated pixels are retained, and uncorrelated noise is excluded. This methodology forms the core of many advanced analysis tools, including Constrained Nonnegative Matrix Factorization, which is widely used to demix signals and reliably identify cell footprints in noisy, dense imaging data [204,205,206].

6.6. Toxicity and Phototoxicity

6.7. Perturbation of Target Property

6.8. pH-Sensitivity

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kulkarni, R.U.; Miller, E.W. Voltage imaging: Pitfalls and potential. Biochemistry 2017, 56, 5171–5177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knöpfel, T.; Song, C. Optical voltage imaging in neurons: Moving from technology development to practical tool. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 719–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klier, P.E.; Roo, R.; Miller, E.W. Fluorescent indicators for imaging membrane potential of organelles. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2022, 71, 102203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gest, A.M.; Sahan, A.Z.; Zhong, Y.; Lin, W.; Mehta, S.; Zhang, J. Molecular spies in action: Genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors light up cellular signals. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 12573–12660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakibi, R.; Yazdipour, F.; Abadijoo, H.; Manoochehri, N.; Pouria, F.R.; Bajooli, T.; Simaee, H.; Abdolmaleki, P.; Khatibi, A.; Abdolahad, M.; et al. From resting potential to dynamics: Advances in membrane voltage indicators and imaging techniques. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2025, 58, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Selim, N.A.; Wojtovich, A.P. Mitochondrial membrane potential and compartmentalized signaling: Calcium, ROS, and beyond. Redox Biol. 2025, 86, 103859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, D.M.; Mironov, V.N.; Shtyrov, A.A.; Kvashnin, I.D.; Mereshchenko, A.S.; Vasin, A.V.; Panov, M.S.; Ryazantsev, M.N. Fluorescence imaging of cell membrane potential: From relative changes to absolute values. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 2435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spruston, N.; Jaffe, D.B.; Williams, S.H.; Johnston, D. Voltage-and space-clamp errors associated with the measurement of electrotonically remote synaptic events. J. Neurophysiol. 1993, 70, 781–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scanziani, M.; Häusser, M. Electrophysiology in the age of light. Nature 2009, 461, 930–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, L.; Salzberg, B.; Grinvald, A. Optical methods for monitoring neuron activity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 1978, 1, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.L.; Yan, P.; Wuskell, J.P.; Loew, L.M.; Antic, S.D. Intracellular long-wavelength voltage-sensitive dyes for studying the dynamics of action potentials in axons and thin dendrites. J. Neurosci. Methods 2007, 164, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lippert, M.T.; Takagaki, K.; Xu, W.; Huang, X.; Wu, J.Y. Methods for voltage-sensitive dye imaging of rat cortical activity with high signal-to-noise ratio. J. Neurophysiol. 2007, 98, 502–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisner, D.; Neher, E.; Taschenberger, H.; Smith, G. Physiology of intracellular calcium buffering. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 2767–2845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, E.A.; Dietrich, D. Buffer mobility and the regulation of neuronal calcium domains. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Belavek, K.J.; Miller, E.W. Origins of Ca2+ imaging with fluorescent indicators. Biochemistry 2021, 60, 3547–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, G.J.; Santamaria, F.; Tanaka, K. Local calcium signaling in neurons. Neuron 2003, 40, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyshedskiy, A.; Lin, J.W. Presynaptic Ca2+ influx at the inhibitor of the crayfish neuromuscular junction: A photometric study at a high time resolution. J. Neurophysiol. 2000, 83, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, S.; Reddish, F.; Zhuo, Y.; Yang, J.J. Fast kinetics of calcium signaling and sensor design. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015, 27, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mutoh, H.; Mishina, Y.; Gallero-Salas, Y.; Knöpfel, T. Comparative performance of a genetically-encoded voltage indicator and a blue voltage sensitive dye for large scale cortical voltage imaging. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fluhler, E.; Burnham, V.G.; Loew, L.M. Spectra, membrane binding, and potentiometric responses of new charge shift probes. Biochemistry 1985, 24, 5749–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Acker, C.D.; Biasci, V.; Judge, G.; Monroe, A.; Sacconi, L.; Loew, L.M. Near-infrared voltage-sensitive dyes based on chromene donor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2305093120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panama, B.K.; Costantino, A.; Nowak, M.W.; Daddario, A.A.; Rasmusson, R.L.; Bett, G.C. Spectral properties of the voltage-sensitive dye di-4-ANBDQBS. Biophys. J. 2023, 122, 383a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, M.; Spitzer, K.W.; Steadman, B.W.; Rees, T.D.; Venable, P.; Taylor, T.; Shibayama, J.; Yan, P.; Wuskell, J.P.; Loew, L.M.; et al. High-precision recording of the action potential in isolated cardiomyocytes using the near-infrared fluorescent dye di-4-ANBDQBS. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2010, 299, H1271–H1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromherz, P.; Hübener, G.; Kuhn, B.; Hinner, M.J. ANNINE-6plus, a voltage-sensitive dye with good solubility, strong membrane binding and high sensitivity. Eur. Biophys. J. 2008, 37, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.W.; Lin, J.Y.; Frady, E.P.; Steinbach, P.A.; Kristan, W.B., Jr.; Tsien, R.Y. Optically monitoring voltage in neurons by photo-induced electron transfer through molecular wires. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 2114–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.L.; Walker, A.S.; Miller, E.W. A photostable silicon rhodamine platform for optical voltage sensing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 10767–10776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarro, M.X.; Gerstner, N.C.; Lipman, S.M.; Dolgonos, G.E.; Miller, E.W. Improved Sensitivity in a Modified Berkeley Red Sensor of Transmembrane Potential. ACS Chem. Biol. 2024, 19, 2214–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.A.; Lee, S.; Roth, R.H.; Natale, S.; Gomez, L.; Taxidis, J.; O’Neill, P.S.; Villette, V.; Bradley, J.; Wang, Z.; et al. A fast and responsive voltage indicator with enhanced sensitivity for unitary synaptic events. Neuron 2024, 112, 3680–3696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topell, S.; Hennecke, J.; Glockshuber, R. Circularly permuted variants of the green fluorescent protein. FEBS Lett. 1999, 457, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, L.; Han, Z.; Platisa, J.; Wooltorton, J.R.; Cohen, L.B.; Pieribone, V.A. Single action potentials and subthreshold electrical events imaged in neurons with a fluorescent protein voltage probe. Neuron 2012, 75, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hochbaum, D.R.; Zhao, Y.; Farhi, S.L.; Klapoetke, N.; Werley, C.A.; Kapoor, V.; Zou, P.; Kralj, J.M.; Maclaurin, D.; Smedemark-Margulies, N.; et al. All-optical electrophysiology in mammalian neurons using engineered microbial rhodopsins. Nat. Methods 2014, 11, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piatkevich, K.D.; Jung, E.E.; Straub, C.; Linghu, C.; Park, D.; Suk, H.J.; Hochbaum, D.R.; Goodwin, D.; Pnevmatikakis, E.; Pak, N.; et al. A robotic multidimensional directed evolution approach applied to fluorescent voltage reporters. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14, 352–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silapetere, A.; Hwang, S.; Hontani, Y.; Fernandez Lahore, R.G.; Balke, J.; Escobar, F.V.; Tros, M.; Konold, P.E.; Matis, R.; Croce, R.; et al. QuasAr Odyssey: The origin of fluorescence and its voltage sensitivity in microbial rhodopsins. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, M.; Vasan, G.; Haziza, S.; Huang, C.; Chrapkiewicz, R.; Luo, J.; Cardin, J.A.; Schnitzer, M.J.; Pieribone, V.A. Dual-polarity voltage imaging of the concurrent dynamics of multiple neuron types. Science 2022, 378, eabm8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiert, F.; Petrov, E.P.; Schultz, P.; Schwille, P.; Weidemann, T. Photophysical behavior of mNeonGreen, an evolutionarily distant green fluorescent protein. Biophys. J. 2018, 114, 2419–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, C.Q.; Wu, S.S.; Cheng, Y.K.; Wu, Y.; Li, Y.M. Comprehensive review of indicators and techniques for optical mapping of intracellular calcium ions. Cereb. Cortex 2024, 34, bhae346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Nido, P.J.; Glynn, P.; Buenaventura, P.; Salama, G.; Koretsky, A.P. Fluorescence measurement of calcium transients in perfused rabbit heart using rhod 2. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1998, 274, H728–H741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gee, K.R.; Brown, K.; Chen, W.U.; Bishop-Stewart, J.; Gray, D.; Johnson, I. Chemical and physiological characterization of fluo-4 Ca2+-indicator dyes. Cell Calc. 2000, 27, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lock, J.T.; Parker, I.; Smith, I.F. A comparison of fluorescent Ca2+ indicators for imaging local Ca2+ signals in cultured cells. Cell Calc. 2015, 58, 638–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Manita, S.; Horigane, S.i.; Sakamoto, M.; Kawakami, R.; Yamaguchi, K.; Otomo, K.; Yokoyama, H.; Kim, R.; et al. Rational engineering of XCaMPs, a multicolor GECI suite for in vivo imaging of complex brain circuit dynamics. Cell 2019, 177, 1346–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Rózsa, M.; Liang, Y.; Bushey, D.; Wei, Z.; Zheng, J.; Reep, D.; Broussard, G.J.; Tsang, A.; Tsegaye, G.; et al. Fast and sensitive GCaMP calcium indicators for imaging neural populations. Nature 2023, 615, 884–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakamoto, M.; Yokoyama, T. Probing neuronal activity with genetically encoded calcium and voltage fluorescent indicators. Neurosci. Res. 2025, 215, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, R.; Imai, S.; Gockel, N.; Lauer, G.; Renken, K.; Wietek, J.; Lamothe-Molina, P.J.; Fuhrmann, F.; Mittag, M.; Ziebarth, T.; et al. PinkyCaMP a mScarlet-based calcium sensor with exceptional brightness, photostability, and multiplexing capabilities. bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koldenkova, V.P.; Nagai, T. Genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators: Properties and evaluation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta—Mol. Cell Res. 2013, 1833, 1787–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mertes, N.; Busch, M.; Huppertz, M.C.; Hacker, C.N.; Wilhelm, J.; Gürth, C.M.; Kühn, S.; Hiblot, J.; Koch, B.; Johnsson, K. Fluorescent and bioluminescent calcium indicators with tuneable colors and affinities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 6928–6935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes, R.M.; Etzler, J.C.; Watts, L.T.; Zheng, W.; Lechleiter, J.D. Chemical calcium indicators. Methods 2008, 46, 143–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullen, A.; Saggau, P. Optical recording from individual neurons in culture. In Modern Techniques in Neuroscience Research; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; pp. 89–126. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Izquierdo, A.; Warren, M.; Riedel, M.; Cho, S.; Lai, S.; Lux, R.L.; Spitzer, K.W.; Benjamin, I.J.; Tristani-Firouzi, M.; Jou, C.J. A near-infrared fluorescent voltage-sensitive dye allows for moderate-throughput electrophysiological analyses of human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. Am. J. Physiol.-Heart Circ. Physiol. 2014, 307, H1370–H1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, E.W. Small molecule fluorescent voltage indicators for studying membrane potential. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2016, 33, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loew, L.M. Design and use of organic voltage sensitive dyes. In Membrane Potential Imaging in the Nervous System and Heart; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 27–53. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, J.; Luo, R.; Otis, T.S.; DiGregorio, D.A. Submillisecond optical reporting of membrane potential in situ using a neuronal tracer dye. J. Neurosci. 2009, 29, 9197–9209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzalez, J.E.; Tsien, R.Y. Improved indicators of cell membrane potential that use fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Chem. Biol. 1997, 4, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, C.E.; Brown, C.W.; Medintz, I.L.; Delehanty, J.B. Intracellular FRET-based probes: A review. Methods Appl. Fluores. 2015, 3, 042006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanda, B.; Blunck, R.; Faria, L.C.; Schweizer, F.E.; Mody, I.; Bezanilla, F. A hybrid approach to measuring electrical activity in genetically specified neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 2005, 8, 1619–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Bayguinov, P.O.; Jackson, M.B. Optical studies of action potential dynamics with hVOS probes. Curr. Opin. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 12, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodford, C.R.; Frady, E.P.; Smith, R.S.; Morey, B.; Canzi, G.; Palida, S.F.; Araneda, R.C.; Kristan, W.B., Jr.; Kubiak, C.P.; Miller, E.W.; et al. Improved PeT molecules for optically sensing voltage in neurons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 1817–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Gou, Y.; Jaeger, D.; St-Pierre, F. Widefield imaging of rapid pan-cortical voltage dynamics with an indicator evolved for one-photon microscopy. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platisa, J.; Vasan, G.; Yang, A.; Pieribone, V.A. Directed evolution of key residues in fluorescent protein inverses the polarity of voltage sensitivity in the genetically encoded indicator ArcLight. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2017, 8, 513–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, A.S.; Farhi, S.L.; Zhao, Y.; Brinks, D.; Zou, P.; Ruangkittisakul, A.; Platisa, J.; Pieribone, V.A.; Ballanyi, K.; Cohen, A.E.; et al. A bright and fast red fluorescent protein voltage indicator that reports neuronal activity in organotypic brain slices. J. Neurosci. 2016, 36, 2458–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsutsui, H.; Jinno, Y.; Tomita, A.; Niino, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Mikoshiba, K.; Miyawaki, A.; Okamura, Y. Improved detection of electrical activity with a voltage probe based on a voltage-sensing phosphatase. J. Physiol. 2013, 591, 4427–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akemann, W.; Mutoh, H.; Perron, A.; Park, Y.K.; Iwamoto, Y.; Knöpfel, T. Imaging neural circuit dynamics with a voltage-sensitive fluorescent protein. J. Neurophysiol. 2012, 108, 2323–2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, L.M.; Kang, B.E.; Baker, B.J. Improving the flexibility of genetically encoded voltage indicators via intermolecular FRET. Biophys. J. 2021, 120, 1927–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.M.; Yokoyama, T.; Sakamoto, M. Imaging voltage with microbial rhodopsins. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 738829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Y.; Wagner, M.J.; Zhong Li, J.; Schnitzer, M.J. Imaging neural spiking in brain tissue using FRET-opsin protein voltage sensors. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.; Davis, H.C.; Wong-Campos, J.D.; Park, P.; Fan, L.Z.; Gmeiner, B.; Begum, S.; Werley, C.A.; Borja, G.B.; Upadhyay, H.; et al. Video-based pooled screening yields improved far-red genetically encoded voltage indicators. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1082–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kralj, J.M.; Douglass, A.D.; Hochbaum, D.R.; Maclaurin, D.; Cohen, A.E. Optical recording of action potentials in mammalian neurons using a microbial rhodopsin. Nat. Methods 2012, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, D.M.; Shtyrov, A.A.; Vyazmin, S.Y.; Vasin, A.V.; Panov, M.S.; Ryazantsev, M.N. Fluorescence of the retinal chromophore in microbial and animal rhodopsins. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 17269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIsaac, R.S.; Engqvist, M.K.; Wannier, T.; Rosenthal, A.Z.; Herwig, L.; Flytzanis, N.C.; Imasheva, E.S.; Lanyi, J.K.; Balashov, S.P.; Gradinaru, V.; et al. Directed evolution of a far-red fluorescent rhodopsin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13034–13039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolaev, D.M.; Mironov, V.N.; Metelkina, E.M.; Shtyrov, A.A.; Mereshchenko, A.S.; Demidov, N.A.; Vyazmin, S.Y.; Tennikova, T.B.; Moskalenko, S.E.; Bondarev, S.A.; et al. Rational Design of Far-Red Archaerhodopsin-3-Based Fluorescent Genetically Encoded Voltage Indicators: From Elucidation of the Fluorescence Mechanism in Archers to Novel Red-Shifted Variants. ACS Phys. Chem. Au 2024, 4, 347–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nikolaev, D.M.; Metelkina, E.M.; Domskii, N.A.; Osadchy, I.R.; Mereshchenko, A.S.; Bondarev, S.A.; Zhouravleva, G.A.; Shtyrov, A.A.; Panov, M.S.; Ryazantsev, M.N. Semirational Protein Engineering Yields Archaerhodopsin-3-Based Fluorescent Genetically Encoded Voltage Indicators with Enhanced Brightness and Red Shifted Absorption Bands. Chem. Bio Eng 2025, 2, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bando, Y.; Sakamoto, M.; Kim, S.; Ayzenshtat, I.; Yuste, R. Comparative evaluation of genetically encoded voltage indicators. Cell Rep. 2019, 26, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rhee, J.K.; Leong, L.M.; Mukim, M.S.I.; Kang, B.E.; Lee, S.; Bilbao-Broch, L.; Baker, B.J. Biophysical parameters of GEVIs: Considerations for imaging voltage. Biophys. J. 2020, 119, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, M.; Vasan, G.; Huang, C.; Haziza, S.; Li, J.Z.; Inan, H.; Schnitzer, M.J.; Pieribone, V.A. Fast, in vivo voltage imaging using a red fluorescent indicator. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 1108–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, Y.; Huang, C.; Li, J.Z.; Grewe, B.F.; Zhang, Y.; Eismann, S.; Schnitzer, M.J. High-speed recording of neural spikes in awake mice and flies with a fluorescent voltage sensor. Science 2015, 350, 1361–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, A.S.; Valenti, R.; Zheng, J.; Wong, A.; Podgorski, K.; Koyama, M.; Kim, D.S.; Schreiter, E.R. A general approach to engineer positive-going eFRET voltage indicators. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki, S.; Tsutsui, H.; Suzuki, K.; Agetsuma, M.; Arai, Y.; Jinno, Y.; Bai, G.; Daniels, M.J.; Okamura, Y.; Matsuda, T.; et al. Genetically encoded bioluminescent voltage indicator for multi-purpose use in wide range of bioimaging. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, P.; Griffin, N.M.; Thakur, D.; Joshi, P.; Nguyen-Le, A.; McCotter, S.; Jain, A.; Saeidi, M.; Kulkarni, P.; Eisdorfer, J.T.; et al. An Autonomous Molecular Bioluminescent Reporter (AMBER) for voltage imaging in freely moving animals. Adv. Biol. 2021, 5, 2100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.; Lee, C.; Kaang, B.K. Imaging and analysis of genetically encoded calcium indicators linking neural circuits and behaviors. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2019, 23, 237–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grynkiewicz, G.; Poenie, M.; Tsien, R.Y. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985, 260, 3440–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barreto-Chang, O.L.; Dolmetsch, R.E. Calcium imaging of cortical neurons using Fura-2 AM. J. Vis. Exp. 2009, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joseph, P. Practical Aspects of Measuring [Ca2+] with Fluorescent Indicators. Methods Cell Biol. 1994, 40, 155–181. [Google Scholar]

- Minta, A.; Kao, J.P.; Tsien, R.Y. Fluorescent indicators for cytosolic calcium based on rhodamine and fluorescein chromophores. J. Biol. Chem. 1989, 264, 8171–8178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, M.; Takeuchi, A.; Hashizume, M.; Kitamura, K.; Kano, M. A highly sensitive fluorescent indicator dye for calcium imaging of neural activity in vitro and in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2014, 39, 1720–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broussard, G.J.; Liang, R.; Tian, L. Monitoring activity in neural circuits with genetically encoded indicators. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2014, 7, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mank, M.; Griesbeck, O. Genetically encoded calcium indicators. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 1550–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyawaki, A.; Llopis, J.; Heim, R.; McCaffery, J.M.; Adams, J.A.; Ikura, M.; Tsien, R.Y. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature 1997, 388, 882–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horikawa, K.; Yamada, Y.; Matsuda, T.; Kobayashi, K.; Hashimoto, M.; Matsu-ura, T.; Miyawaki, A.; Michikawa, T.; Mikoshiba, K.; Nagai, T. Spontaneous network activity visualized by ultrasensitive Ca2+ indicators, yellow Cameleon-Nano. Nat. Methods 2010, 7, 729–732. [Google Scholar]

- Nakai, J.; Ohkura, M.; Imoto, K. A high signal-to-noise Ca2+ probe composed of a single green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19, 137–141. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, L.; Hires, S.A.; Mao, T.; Huber, D.; Chiappe, M.E.; Chalasani, S.H.; Petreanu, L.; Akerboom, J.; McKinney, S.A.; Schreiter, E.R.; et al. Imaging neural activity in worms, flies and mice with improved GCaMP calcium indicators. Nat. Methods 2009, 6, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.W.; Wardill, T.J.; Sun, Y.; Pulver, S.R.; Renninger, S.L.; Baohan, A.; Schreiter, E.R.; Kerr, R.A.; Orger, M.B.; Jayaraman, V.; et al. Ultrasensitive fluorescent proteins for imaging neuronal activity. Nature 2013, 499, 295–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Araki, S.; Wu, J.; Teramoto, T.; Chang, Y.F.; Nakano, M.; Abdelfattah, A.S.; Fujiwara, M.; Ishihara, T.; Nagai, T.; et al. An expanded palette of genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators. Science 2011, 333, 1888–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Prole, D.L.; Shen, Y.; Lin, Z.; Gnanasekaran, A.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Zhou, H.; Chen, S.W.; Usachev, Y.M.; et al. Red fluorescent genetically encoded Ca2+ indicators for use in mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum. Biochem. J. 2014, 464, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dana, H.; Mohar, B.; Sun, Y.; Narayan, S.; Gordus, A.; Hasseman, J.P.; Tsegaye, G.; Holt, G.T.; Hu, A.; Walpita, D.; et al. Sensitive red protein calcium indicators for imaging neural activity. eLife 2016, 5, e12727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baird, G.S.; Zacharias, D.A.; Tsien, R.Y. Circular permutation and receptor insertion within green fluorescent proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1999, 96, 11241–11246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagai, T.; Sawano, A.; Park, E.S.; Miyawaki, A. Circularly permuted green fluorescent proteins engineered to sense Ca2+. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 3197–3202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doronin, D.; Barykina, N.; Subach, O.; Sotskov, V.; Plusnin, V.; Ivleva, O.; Isaakova, E.; Varizhuk, A.; Pozmogova, G.; Malyshev, A.; et al. Genetically encoded calcium indicator with NTnC-like design and enhanced fluorescence contrast and kinetics. BMC Biotechnol. 2018, 18, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subach, O.M.; Sotskov, V.P.; Plusnin, V.V.; Gruzdeva, A.M.; Barykina, N.V.; Ivashkina, O.I.; Anokhin, K.V.; Nikolaeva, A.Y.; Korzhenevskiy, D.A.; Vlaskina, A.V.; et al. Novel genetically encoded bright positive calcium indicator NCaMP7 based on the mNeonGreen fluorescent protein. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, T.J.; Waters, J.C. Assessing camera performance for quantitative microscopy. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014, 123, 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Zecevic, D.; Djurisic, M.; Cohen, L.B.; Antic, S.; Wachowiak, M.; Falk, C.X.; Zochowski, M.R. Imaging nervous system activity with voltage-sensitive dyes. Curr. Protoc. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phil Brooks, F., III; Davis, H.C.; Wong-Campos, J.D.; Cohen, A.E. Optical constraints on two-photon voltage imaging. Neurophotonics 2024, 11, 035007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilt, B.A.; Fitzgerald, J.E.; Schnitzer, M.J. Photon shot noise limits on optical detection of neuronal spikes and estimation of spike timing. Biophys. J. 2013, 104, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjulson, L.; Miesenbock, G. Optical recording of action potentials and other discrete physiological events: A perspective from signal detection theory. Am. J. Physiol. 2007, 22, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiepas, A.; Voorand, E.; Mubaid, F.; Siegel, P.M.; Brown, C.M. Optimizing live-cell fluorescence imaging conditions to minimize phototoxicity. J. Cell Sci. 2020, 133, jcs242834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Cong, L.; Shi, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, B.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, Z.Q.; Xu, N.; Mu, Y.; et al. Volumetric voltage imaging of neuronal populations in the mouse brain by confocal light-field microscopy. Nat. Methods 2024, 21, 2160–2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheppard, C.J.; Gan, X.; Gu, M.; Roy, M. Signal-to-noise ratio in confocal microscopes. In Handbook of Biological Confocal Microscopy; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 442–452. [Google Scholar]

- Homma, R.; Baker, B.J.; Jin, L.; Garaschuk, O.; Konnerth, A.; Cohen, L.B.; Zecevic, D. Wide-field and two-photon imaging of brain activity with voltage-and calcium-sensitive dyes. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2009, 364, 2453–2467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Liang, Y.; Chen, S.; Hsu, C.L.; Chavarha, M.; Evans, S.W.; Shi, D.; Lin, M.Z.; Tsia, K.K.; Ji, N. Kilohertz two-photon fluorescence microscopy imaging of neural activity in vivo. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Z.; Fan, J.; Deng, F.; Wu, Z.; Xiao, G.; He, J.; et al. Real-time denoising enables high-sensitivity fluorescence time-lapse imaging beyond the shot-noise limit. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, S.; Tang, Z.F.; McMillen, D.R. A framework to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio for quantitative fluorescence microscopy. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0330718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, T.; Yuan, Y.; Mitra, S.; Gyongy, I.; Nolan, M.F. Single photon kilohertz frame rate imaging of neural activity. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2203018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.H.; Jang, J.; Milosevic, M.M.; Antic, S.D. Population imaging discrepancies between a genetically-encoded calcium indicator (GECI) versus a genetically-encoded voltage indicator (GEVI). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinkard, H.; Corbin, K.; Krummel, M.F. Spatiotemporal rank filtering improves image quality compared to frame averaging in 2-photon laser scanning microscopy. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0150430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weigert, M.; Schmidt, U.; Boothe, T.; Müller, A.; Dibrov, A.; Jain, A.; Wilhelm, B.; Schmidt, D.; Broaddus, C.; Culley, S.; et al. Content-aware image restoration: Pushing the limits of fluorescence microscopy. Nat. Methods 2018, 15, 1090–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukamel, E.A.; Nimmerjahn, A.; Schnitzer, M.J. Automated analysis of cellular signals from large-scale calcium imaging data. Neuron 2009, 63, 747–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabbay, M.; Brennan, C.; Kaplan, E.; Sirovich, L. A principal components-based method for the detection of neuronal activity maps: Application to optical imaging. NeuroImage 2000, 11, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, M.; Han, S.; Park, P.; Kim, G.; Cho, E.S.; Sim, J.; Lee, K.H.; Kim, S.; Tian, H.; Böhm, U.L.; et al. Statistically unbiased prediction enables accurate denoising of voltage imaging data. Nat. Methods 2023, 20, 1581–1592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]