Emerging Microfluidic Plasma Separation Technologies for Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Moving Beyond Conventional Centrifugation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conventional Techniques for Plasma Separation

3. Microfluidic Techniques for Plasma Separation

3.1. Passive Techniques for Plasma Separation in Microfluidics

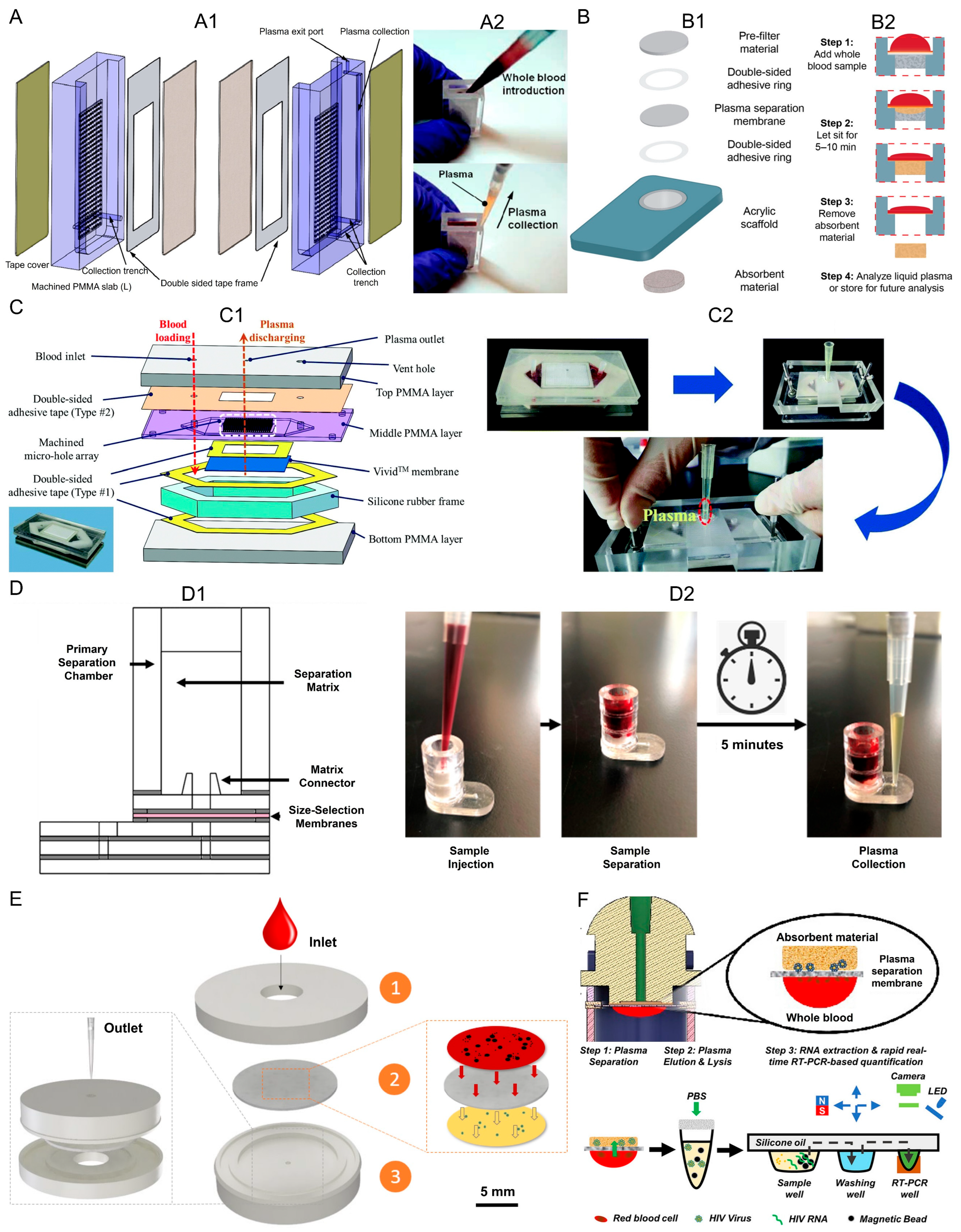

3.1.1. Filtration-Based Techniques

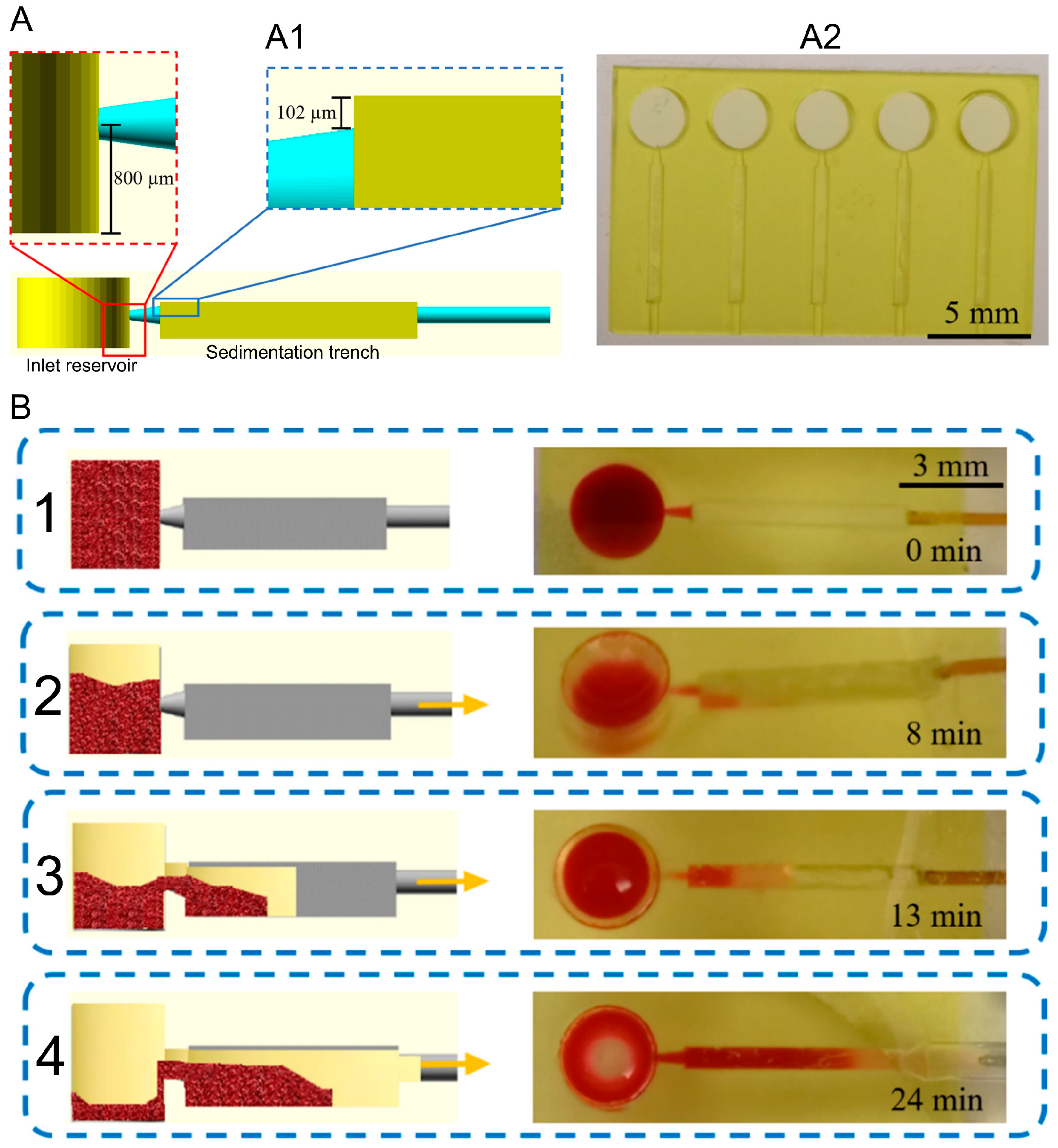

3.1.2. Sedimentation-Based Techniques

3.1.3. Passive Flow-Driven Techniques

| Reference | Sample Volume | Extraction Efficiency | Yield | Blood Sample | Extraction Time | Hematocrit Level | Final Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-Sedimentation-based method | |||||||

| [27] | 12 μL | NA | ~5 µL | Undiluted and diluted blood | 35 min flow + 8 min pre-sedimentation | NA | Comparison between different 3D designs for plasma separation |

| II-Passive Flow-Driven methods | |||||||

| [28] | 25 μL | 96% | 7.23 μL | Whole Blood | 10 min | 44% | NT-proBNP detection |

| [29] | NA | (99.97–93.5%) | 1–6% | Whole Blood | NA | (8.16–73.4%) | Colorimetric detection of creatinine and urea |

| [30] | 2–5 μL | 88% | NA | Whole Blood | <1 min | 30–45% | Extraction of the plasma with lower hematocrit |

| [32] | Cont. System | 97% for RBCs | 28% | Whole Blood | 2000 μL/h | NA | plasma separation |

| [33] | Simulation | ~64% | 25–35% | Whole blood | NA | 10.4% | Optimization of chip geometry capable of efficiently separating plasma |

| [34] | Simulation | NA | 98% (in theory) | Whole Blood | NA | NA | Plasma-separating microchannel design and simulation |

| [35] | NA | 84–99.9% | NA | Whole Blood | 0.8 mL/min | 0–45% | Observation of Fahraeus effect, the Fahraeus–Lindquist effect, and the Zweifach–Fung effect on plasma separation |

| [36] | NA | 99.9% for RBC, 95.4% for PLTs | 80 μL | Whole Blood | 10 min | NA | Platelet or plasma separation |

| [37] | 160 μL | 99% | 22 μL | Whole Blood | 10 min | 45% | Cervical cancer detection |

3.1.4. Superhydrophobic Membrane

3.1.5. Paper-Based Techniques

3.2. Active Techniques for Plasma Separation in Microfluidics

3.2.1. Active Pump-Assisted Techniques

3.2.2. Centrifugation-Based Techniques

3.2.3. Dielectrophoresis

3.2.4. Acoustic Wave-Based Techniques

| Reference | Sample Volume | Extraction Efficiency | Yield | Blood Sample | Extraction Time | Hematocrit Level | Final Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-Dielectrophoretic methods | |||||||

| [68] | 10 μL | 99.98% ± 0.02% | 2.2 μL | Whole Blood | 4 min | 15–65% | Plasma separation |

| [69] | 5 μL | 90% | 10–100 nL | Whole Blood | 4 min | NA | Determination of blood lithium-ion concentration |

| II-Acoustic Wave-based methods | |||||||

| [71] | 30 μL/min | ~100% | 55.6% | Whole Blood | ~250 ms | 40% | Microparticle separation |

| [72] | 115 µL/min | >99.99% | 23 µL/min | Whole Blood | Cont. System | NA | Blood sampling and plasma separation |

| [73] | NA | >90% | NA | Whole Blood | NA | NA | WBC/RBC/platelet separation |

| [74] | 3.5 mL | 58.42% for plateletes, 99.96% for RBCs | NA | Diluted with PBS | 50 μL/min | NA | Blood cell separation |

| [75] | 5 mL | NA | NA | Diluted blood with PBS | 200 s | ~50% | Measuring viscosity and aggregation of blood sample |

3.2.5. Magnetic Separation-Based Techniques

4. Conclusions and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khatoon, S.; Ahmad, G. A Review on the Recent Developments in Passive Plasma Separators and Lab-on-Chip Microfluidic Devices. Eng. Proc. 2023, 31, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USFDA. Recommendations for Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA) Waiver Applications for Manufacturers of In Vitro Diagnostic Devices: Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. U.S. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/109582/download?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Trick, A.Y.; Ngo, H.T.; Nambiar, A.H.; Morakis, M.M.; Chen, F.E.; Chen, L.; Hsieh, K.; Wang, T.H. Filtration-Assisted Magnetofluidic Cartridge Platform for HIV RNA Detection from Blood. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 945–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Orozco, F.; Rando-Segura, A.; Martínez-Camprecios, J.; Salmeron, P.; Najarro-Centeno, A.; Esteban, À.; Quer, J.; Buti, M.; Pumarola-Suñe, T.; Rodríguez-Frías, F. Utility of the Cobas® Plasma Separation Card as a Sample Collection Device for Serological and Virological Diagnosis of Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, E.; Limo, E.; Pagani, L.; Monza, N.; Serrao, S.; Denti, V.; Astarita, G.; Paglia, G. Revolutionizing Blood Collection: Innovations, Applications, and the Potential of Microsampling Technologies for Monitoring Metabolites and Lipids. Metabolites 2024, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maria, M.S.; Chandra, T.S.; Sen, A.K. Capillary flow-driven blood plasma separation and on-chip analyte detection in microfluidic devices. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2017, 21, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, S.; Kumar, Y.B.V.; Prabhakar, A.; Joshi, S.S.; Agrawal, A. Passive blood plasma separation at the microscale: A review of design principles and microdevices. J. Micromech. Microeng. 2015, 25, 083001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Nunna, B.B.; Talukder, N.; Etienne, E.E.; Lee, E.S. Blood plasma self-separation technologies during self-driven flow in microfluidic platforms. Bioengineering 2021, 8, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, H.W.; Bhagat, A.A.S.; Lee, W.C.; Huang, S.; Han, J.; Lim, C.T. Microfluidic Devices for Blood Fractionation. Micromachines 2011, 2, 319–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielczarek, W.S.; Obaje, E.A.; Bachmann, T.T.; Kersaudy-Kerhoas, M. Microfluidic blood plasma separation for medical diagnostics: Is it worth it? Lab Chip 2016, 16, 3441–3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lippi, G.; Salvagno, G.L.; Montagnana, M.; Manzato, F.; Guidi, G.C. Influence of the Centrifuge Time of Primary Plasma Tubes on Routine Coagulation Testing. Blood Coagul. Fibrinolysis 2007, 18, 525–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Iacovetti, G.; Rahimian, A.; Hong, S.; Epperson, J.; Neal, C.; Pan, T.; Le, A.; Kendall, E.; Melton, K.; et al. Clinical Evaluation of the Torq Zero Delay Centrifuge System for Decentralized Blood Collection and Stabilization. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madadi, H.; Casals-Terré, J.; Mohammadi, M. Self-Driven Filter-Based Blood Plasma Separator Microfluidic Chip for Point-of-Care Testing. Biofabrication 2015, 7, 025007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Z.; Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Feng, Z.; Dai, S.; Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Sheu, C.-L.; Guo, W. High-Performance Passive Plasma Separation on OSTE Pillar Forest. Biosensors 2021, 11, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catarino, S.O.; Rodrigues, R.O.; Pinho, D.; Miranda, J.M.; Minas, G.; Lima, R. Blood Cells Separation and Sorting Techniques of Passive Microfluidic Devices: From Fabrication to Applications. Micromachines 2019, 10, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deiana, G.; Smith, S. 3D Printed Devices for the Separation of Blood Plasma from Capillary Samples. Micromachines 2024, 15, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, H.; Qin, Z.; Li, X.; Pan, Y.; Xu, H.; Pan, P.; Song, P.; Liu, X. Paper-Based All-in-One Origami Nanobiosensor for Point-of-Care Detection of Cardiac Protein Markers in Whole Blood. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 3574–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilroy, C.; Silver, C.D.; Kunstmann-Olsen, C.; Miller, L.M.; Johnson, S.D.; Krauss, T.F. A Passive Blood Separation Sensing Platform for Point-of-Care Devices. npj Biosens. 2025, 2, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Dai, P.; Su, W.; Fang, X.; You, H. Innovative Microfluidic Chip for Quantitative Plasma Separation in POCT. Chem. Eng. J. 2025, 514, 163375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Sun, C.; Dai, P.; Xian, Z.; Su, W.; Zheng, C.; Xing, D.; Xu, X.; You, H. Capillary Force-Driven Quantitative Plasma Separation Method for Application of Whole Blood Detection Microfluidic Chip. Micromachines 2024, 15, 619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Cui, A.; Xiang, D.; Wang, Q.; Huang, J.; Liu, J.; Yang, X.; Wang, K. A Microfluidic Chip with Integrated Plasma Separation for Sample-to-Answer Detection of Multiple Chronic Disease Biomarkers in Whole Blood. Talanta 2024, 280, 126701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, H.T.; Jin, M.; Trick, A.Y.; Chen, F.E.; Chen, L.; Hsieh, K.; Wang, T.-H. Sensitive and Quantitative Point-of-Care HIV Viral Load Quantification from Blood Using a Power-Free Plasma Separation and Portable Magnetofluidic Polymerase Chain Reaction Instrument. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qiu, X.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, K.; Ge, S.; Xia, N.; Mauk, M.G. A plasma separator with a multifunctional deformable chamber equipped with a porous membrane for point-of-care diagnostics. Analyst 2020, 145, 6138–6147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Mauk, M.; Gross, R.; Bushman, F.D.; Edelstein, P.H.; Collman, R.G.; Bau, H.H. Membrane-Based, Sedimentation-Assisted Plasma Separator for Point-of-Care Applications. Anal. Chem. 2013, 85, 10463–10470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baillargeon, K.R.; Murray, L.P.; Deraney, R.N.; Mace, C.R. High-Yielding Separation and Collection of Plasma from Whole Blood Using Passive Filtration. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 16245–16252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, M.; Weng, Z.; Wang, J.; Zeng, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, S.; et al. High-Efficiency Plasma Separator Based on Immunocapture and Filtration. Micromachines 2020, 11, 352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Rey, S.; Nielsen, J.B.; Nordin, G.P.; Woolley, A.T.; Basabe-Desmonts, L.; Benito-Lopez, F. High-Resolution 3D Printing Fabrication of a Microfluidic Platform for Blood Plasma Separation. Polymers 2022, 14, 2537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strohmaier-Nguyen, D.; Horn, C.; Baeumner, A.J. Sample-to-Answer Lateral Flow Assay with Integrated Plasma Separation and NT-proBNP Detection. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2024, 416, 3107–3115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, M.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, S.; Maurya, A.; Gandhi, S.; Arun, R.K. Design of a Compact and Cost-Effective Blood Plasma Separation Device Utilizing Biophysical Effects from Whole Blood with Simultaneous Colorimetric Detection of Creatinine and Urea. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 091911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Talukder, N.; Nunna, B.B.; Lee, E.S. Dean Vortex-Enhanced Blood Plasma Separation in Self-Driven Spiral Microchannel Flow with Cross-Flow Microfilters. Biomicrofluidics 2024, 18, 014104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laxmi, V.; Tripathi, S.; Joshi, S.S.; Agrawal, A. Separation and Enrichment of Platelets from Whole Blood Using a PDMS-Based Passive Microdevice. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 4792–4801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Anoop, K.; Huang, C.; Sadr, R.; Gupte, R.; Dai, J.; Han, A. A Circular Gradient-Width Crossflow Microfluidic Platform for High-Efficiency Blood Plasma Separation. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 354, 131180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Ye, T.; Wang, S.; Li, X.; Ul Haq, R. Numerical Design of a Highly Efficient Microfluidic Chip for Blood Plasma Separation. Phys. Fluids 2020, 32, 031903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loganathan, A.K.; Devaraj, R.; Krishnamoorthy, L. Revolutionizing Plasma Separation: Cutting-Edge Design, Simulation, and Optimization Techniques in Microfluidics Using COMSOL. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2023, 27, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, S.P.; Sharma, A.; Agrawal, A. A Continuum-Based Numerical Simulation of Blood Plasma Separation in a Complex Microdevice: Quantification of Bifurcation Law. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 159, 107967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, L.M.; Bhatt, K.H.; Haithcock, D.W.; Prabhakarpandian, B. Blood Component Separation in Straight Microfluidic Channels. Biomicrofluidics 2023, 17, 054106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyvani, F.; Debnath, N.; Ayman Saleh, M.; Poudineh, M. An Integrated Microfluidic Electrochemical Assay for Cervical Cancer Detection at Point-of-Care Testing. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 6761–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Liao, S.C.; Song, J.; Mauk, M.G.; Li, X.; Wu, G.; Ge, D.; Greenberg, R.M.; Yang, S.; Bau, H.H. A High-Efficiency Superhydrophobic Plasma Separator. Lab Chip 2016, 16, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, J.; Pan, D.; Ni, J.; Yin, K.; Zhang, Q.; Ding, Y.; Li, A.; Wu, D.; Shen, Z. High-Performance Blood Plasma Separation Based on a Janus Membrane Technique and RBC Agglutination Reaction. Lab Chip 2022, 22, 4382–4392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Min, S.; Zhan, T.; Huang, Y.; Niu, H.; Xu, B. Humidity-Enhanced Microfluidic Plasma Separation on Chinese Xuan-Papers. Lab Chip 2024, 24, 4379–4389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gautam, N.; Verma, R.; Ram, R.; Singh, J.; Sarkar, A. Development of a Biodegradable Microfluidic Paper-Based Device for Blood–Plasma Separation Integrated with Non-Enzymatic Electrochemical Detection of Ascorbic Acid. Talanta 2024, 266, 125019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgos-Flórez, F.; Rodríguez, A.; Cervera, E.; De Ávila, M.; Sanjuán, M.; Villalba, P.J. Microfluidic Paper-Based Blood Plasma Separation Device as a Potential Tool for Timely Detection of Protein Biomarkers. Micromachines 2022, 13, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Park, H.; Chung, D.R.; Kim, T.; Park, E.; Kang, M. A Self-Pressure-Driven Blood Plasma-Separation Device for Point-of-Care Diagnostics. Talanta 2022, 247, 123562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuo, Z.Q.; Pan, J.Z.; Fang, Q. An Integrated Microfluidic System for Multi-Target Biochemical Analysis of a Single Drop of Blood. Talanta 2022, 249, 123585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Luo, J.; Zhu, Y.; Kong, F.; Mao, G.; Ming, T.; Xing, Y.; Liu, J.; Dai, Y.; Yan, S.; et al. Multifunctional Self-Driven Origami Paper-Based Integrated Microfluidic Chip to Detect CRP and PAB in Whole Blood. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 208, 114225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tamimi, M.; Altarawneh, S.; Alsallaq, M.; Ayoub, M. Efficient and Simple Paper-Based Assay for Plasma Separation Using Universal Anti-H Agglutinating Antibody. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 40109–40115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, T.; Cui, Q.; Feng, X.; Feng, S.; Li, M.; Yang, Y.; Hosokawa, Y.; Tian, G.; Shen, A.Q.; et al. Active Microfluidic Platforms for Particle Separation and Integrated Sensing Applications. ACS Sens. 2025, 10, 5299–5313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayanamurthy, V.; Jeroish, Z.E.; Bhuvaneshwari, K.S.; Bayat, P.; Premkumar, R.; Samsuri, F.; Yusoff, M.M. Advances in Passively Driven Microfluidics and Lab-on-Chip Devices: A Comprehensive Literature Review and Patent Analysis. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 11652–11680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.N.; Chen, P.C.; Chen, P.S.; Jair, Y.C.; Wu, Y.H. Engineering a Vacuum-Actuated Peristaltic Micropump with Novel Microchannel Design to Rapidly Separate Blood Plasma with Extremely Low Hemolysis. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2024, 379, 115845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zeng, Q.; Ren, J.; Zhang, M.; Shi, G. A Membrane-Based Plasma Separator Coupled with Ratiometric Fluorescent Sensor for Biochemical Analysis in Whole Blood. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2025, 36, 110494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guevara-Pantoja, P.E.; Alvarez-Braña, Y.; Mercader-Ruiz, J.; Benito-Lopez, F.; Basabe-Desmonts, L. A Microfluidic Device for Passive Separation of Platelet-Rich Plasma from Whole Blood. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 4886–4897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leong, S.Y.; Lok, W.W.; Goh, K.Y.; Ong, H.B.; Tay, H.M.; Su, C.; Kong, F.; Upadya, M.; Wang, W.; Radnaa, E.; et al. High-Throughput Microfluidic Extraction of Platelet-Free Plasma for MicroRNA and Extracellular Vesicle Analysis. ACS Nano 2024, 18, 6623–6637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonçalves, M.; Gonçalves, I.M.; Borges, J.; Faustino, V.; Soares, D.; Vaz, F.; Minas, G.; Lima, R.; Pinho, D. Polydimethylsiloxane Surface Modification of Microfluidic Devices for Blood Plasma Separation. Polymers 2024, 16, 1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, T.N.; Chen, P.C.; Chen, P.S. Developing an Extremely High Flow Rate Pneumatic Peristaltic Micropump for Blood Plasma Separation with Inertial Particle Focusing Technique from Fingertip Blood with Lancets. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 36th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems (MEMS), Munich, Germany, 15–19 January 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1045–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, K.; Chan, H.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Tian, C.; Niu, Y. Flow-Rate-Insensitive Plasma Extraction by the Stabilization and Acceleration of Secondary Flow in the Ultralow Aspect Ratio Spiral Channel. Anal. Chem. 2023, 95, 18278–18286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Suarez, A.M.; Stybayeva, G.; Carey, W.A.; Revzin, A. Automated Microfluidic System with Active Mixing Enables Rapid Analysis of Biomarkers in 5 μL of Whole Blood. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 9706–9714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Z.X.; Wu, C.C.; Huang, N.T. A Microfluidic Platform with an Embedded Miniaturized Electrochemical Sensor for On-Chip Plasma Extraction Followed by In Situ High-Sensitivity C-Reactive Protein (hs-CRP) Detection. Biosensors 2022, 12, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Faqheri, W.; Thio, T.H.; Qasaimeh, M.A.; Dietzel, A.; Madou, M.; Al-Halhouli, A.A. Particle/Cell Separation on Microfluidic Platforms Based on Centrifugation Effect: A Review. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2017, 21, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, T.; Min, S.; Wu, X.; Wu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Liu, J.; Chen, Z.; Niu, H.; Xu, B. Atmospheric Pressure Difference Centrifuge for Stable and Consistent Plasma Separation. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 426, 137143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oksuz, C.; Bicmen, C.; Tekin, H.C. Dynamic Fluidic Manipulation in Microfluidic Chips with Dead-End Channels through Spinning: The Spinochip Technology for Hematocrit Measurement, White Blood Cell Counting and Plasma Separation. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 1926–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatami, A.; Saadatmand, M.; Garshasbi, M. Cell-Free Fetal DNA (cffDNA) Extraction from Whole Blood by Using a Fully Automatic Centrifugal Microfluidic Device Based on Displacement of Magnetic Silica Beads. Talanta 2024, 267, 125245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajeh, M.M.; Saadatmand, M. Blood Plasma Separation and Transfer on a Centrifugal Microfluidic Disk: Numerical Analysis and Experimental Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 30th National and 8th International Iranian Conference on Biomedical Engineering (ICBME), Tehran, Iran, 30 November–2 December 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi, R.; Pishbin, E.; Eghbal, M.; Abrinia, K. Real-Time Monitoring and Actuation of a Hybrid Siphon Valve for Hematocrit-Independent Plasma Separation from Whole Blood. Analyst 2023, 148, 5456–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Guo, J.; Guo, J. Alphalisa Immunoassay Enabled Centrifugal Microfluidic System for “One-Step” Detection of Pepsinogen in Whole Blood. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2023, 376, 133048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peshin, S.; Madou, M.; Kulinsky, L. Integrating Bio-Sensing Array with Blood Plasma Separation on a Centrifugal Platform. Sensors 2023, 23, 1710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami, A.; Saadatmand, M. Extremely Precise Blood-Plasma Separation from Whole Blood on a Centrifugal Microfluidic Disk (Lab-on-a-Disk) Using Separator Gel. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarno, B.; Heineck, D.; Heller, M.J.; Ibsen, S.D. Dielectrophoresis: Developments and Applications from 2010 to 2020. Electrophoresis 2021, 42, 539–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiaridoost, S.; Habibiyan, H.; Ghafoorifard, H. A Microfluidic Device to Separate High-Quality Plasma from Undiluted Whole Blood Sample Using an Enhanced Gravitational Sedimentation Mechanism. Anal. Chim. Acta 2023, 1239, 340641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, T.; Tokeshi, M.; Fan, S.K. Determination of Blood Lithium-Ion Concentration Using Digital Microfluidic Whole-Blood Separation and Preloaded Paper Sensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 195, 113631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kersaudy-Kerhoas, M.; Sollier, E. Micro-Scale Blood Plasma Separation: From Acoustophoresis to Egg-Beaters. Lab Chip 2013, 13, 3323–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.; Hong, S.; Cho, S.; Han, B.; Kim, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Nam, J. Advanced Design of Indented-Standing Surface Acoustic Wave (i-SSAW) Device for Platelet-Derived Microparticle Separation from Whole Blood. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 423, 136742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, A.; Larsson, S.M.; Lenshof, A.; Qiu, W.; Baasch, T.; Nilsson, L.; Gram, M.; Ley, D.; Laurell, T. Acoustophoresis-Based Blood Sampling and Plasma Separation for Potentially Minimizing Sampling-Related Blood Loss. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2025, 63, 2218–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Xia, J.; Upreti, N.; David, E.; Rufo, J.; Gu, Y.; Yang, K.; Yang, S.; Xu, X.; Kwun, J.; et al. An Acoustofluidic Device for the Automated Separation of Platelet-Reduced Plasma from Whole Blood. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Colditz, M.; Fakhfouri, A.; Kronstein-Wiedemann, R.; Ivanova, K.; Hölig, K.; Tonn, T.; Winkler, A. Validation of Blood Plasma Purification Using Mass-Producible Acoustofluidic Chips in Comparison to Conventional Centrifugation. SSRN 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y.J. Simultaneous Viscosity Measurement of Suspended Blood and Plasma Separated by an Ultrasonic Transducer. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vemulapati, S.; Erickson, D. H.E.R.M.E.S: Rapid Blood–Plasma Separation at the Point-of-Need. Lab Chip 2018, 18, 3285–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vemulapati, S.; Erickson, D. Portable Resource-Independent Blood–Plasma Separator. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 14824–14828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiriny, A.; Bayareh, M. On magnetophoretic separation of blood cells using a Halbach array of magnets. Meccanica 2020, 55, 1903–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Oh, J.; Lee, M.S.; Um, E.; Jeong, J.; Kang, J.H. Enhanced Diamagnetic Repulsion of Blood Cells Enables Versatile Plasma Separation for Biomarker Analysis in Blood. Small 2021, 17, 2100797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y.; Hu, S.; Li, R.; Tan, X.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, S.; Yang, H. Power-Free Plasma Separation Based on Negative Magnetophoresis for Rapid Biochemical Analysis. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2024, 10, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reference | Sample Volume | Extraction Efficiency | Yield | Blood Sample | Extraction Time | Hematocrit Level | Final Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [16] | 50 µL | NA | 56.88% | Whole blood | 87 s | NA | Capillary blood plasma separation |

| [17] | 20 μL | 45% | 3 μL | Whole blood | 20 min | NA | Detection of cardiac protein markers |

| [18] | ~40 µL | 97% | NA | Diluted with PBS-EDTA | 12–15 min | NA | C-reactive protein testing |

| [19] | NA | 99.8% | 5–30 μL | Whole blood | 5 min | 48% | Plasma separation |

| [20] | 100–200 μL | 99.8% | 5–30 μL | Whole blood | 20 min | 48% | Accurate plasma separation |

| [21] | 200 μL | NA | ~50 μL | Whole blood | 6–10 min | NA | Detection of multiple chronic disease biomarkers |

| [22] | 100 μL | 96% | NA | Whole blood | 3 min | NA | HIV viral load quantification |

| [23] | 2.3 mL | NA | ~130 μL | Whole blood | 8 min | NA | Plasma separation |

| [24] | 1.8 mL | 95.5 ± 3.5% to 81.5 ± 12.1% | 275 ± 33.5 µL | Whole blood | <7 min | NA | Plasma separation for HIV detection |

| [25] | ~115–120 µL | 53.8% | ~65.6 ± 3.9 µL | Whole blood | 10 min | 20–50% | Immunochromatographic assay for tetanus antibodies |

| [26] | 400 µL | ~100% | ~131.8 ± 3.4 µL | Whole blood | 5 min | 65% | Immunocapture plasma separation for clinical assays |

| Reference | Sample Volume | Extraction Efficiency | Yield | Blood Sample | Extraction Time | Hematocrit Level | Final Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I-Superhydrophobic membrane-based methods | |||||||

| [38] | 200 µL | >84.5 ± 25.8% | 65 ± 21.5 µL | Whole blood | <10 min | NA | Plasma separation |

| [39] | 10–100 µL | 99.99% | ~80% | Whole blood | 20–80 s | ~45% | Plasma separation |

| II-Paper-based methods | |||||||

| [40] | 10–40 μL | 99.99% | ~3.3 μL (60.1%) | Whole Blood | 5 min | ~45% | Plasma separation on Chinese Xuan papers |

| [41] | 80 μL | NA | NA | Whole Blood | 2–4 min | 27–55% | Non-enzymatic electrochemical detection of ascorbic acid |

| [42] | 300 μL | 98% | 50 μL | Whole Blood | 220 s | 45% | Detection of protein Biomarkers |

| [43] | NA | NA | NA | Whole Blood | 1 min | NA | NA detection |

| [44] | 30 μL | NA | ~10 μL | Whole Blood | 11 min | 30–50% | Multi-target biochemical analysis |

| [45] | 73.3 μL | 99.91% | >80% | Whole Blood | 75 s | NA | Detection of CRP and PAB |

| [46] | 7 μL | 72% | 90–110% | Whole Blood | NA | 39.98 ± 4.3% | Plasma separation on filter paper using the anti-H agglutinating antibody |

| Reference | Sample Volume | Extraction Efficiency | Yield | Blood Sample | Extraction Time | Hematocrit Level | Final Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [49] | 5 μL | 98.5% | NA | Diluted with PBS | <1 min | NA | Plasma separation |

| [50] | 0.6 mL | NA | 100 µL | Diluted with PBS | >5 min | NA | Analysis of glucose, cholesterol from whole blood |

| [51] | 1 mL | 98% for RBC and 96% WBC | 250–300 µL | Whole Blood | 40–65 min | 45–55% | Platelet-rich plasma separation |

| [52] | 3 mL | ~99.99% | NA | Diluted with PBS | 30 min | ~25% | MicroRNA and extracellular vesicle analysis |

| [53] | 5 mL | NA | NA | Diluted with physiological salt solution (PSS) | 20 min | NA | Surface modification of PDMS microfluidics for plasma separation |

| [54] | 180 μL | 97% | NA | Diluted blood with PBS | 3 min | NA | Plasma separation with pneumatic peristaltic micropump |

| [55] | NA | 99.70% including PLTs | NA | Diluted blood | NA | 0.1–3% | Plasma separation |

| [56] | 5 μL | NA | 1 μL | Whole Blood | 2 min | Adult donor blood | Determination of glucose concentration in blood |

| [57] | 400 μL | NA | 100 μL | Whole Blood | 7 min | <50% | C-reactive protein (CRP) detection |

| Reference | Sample Volume | Extraction Efficiency | Yield | Blood Sample | Extraction Time | Hematocrit Level | Final Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [59] | 15 µL | ~99.99% | ~93% | Whole Blood | 250 s | 10–60% | Plasma separation |

| [60] | 10 µL | 99% for RBC and 93% WBC | NA | Whole Blood | 10 min | ~45% | Hematocrit measurement, white blood cell counting and plasma separation |

| [61] | 3 mL | 99% | 1.3 mL | Whole Blood | 300 s | 45% | Cell-free fetal DNA extraction |

| [62] | 70 μL | NA | 37.7 μL | Whole Blood | 8 min | 45% | Plasma separation |

| [63] | 2 mL | >99% | 40–70% | Whole Blood | 5 min | <20–50% | Effect of siphon valve on plasma separation of whole blood with different HCT levels. |

| [64] | 50 μL | 99% | NA | Whole Blood | 50 s | 48%, 24%, 12% | Early detection of pepsinogen |

| [65] | 20 μL | 99.99% | NA | Whole Blood | 7 min | NA | Plasma separation and bio-sensing |

| [66] | 3 mL | 99.992% | 90% | Whole Blood | 300 s | 45% | Plasma separation with using separator gel on disk |

| Reference | Sample Volume | Extraction Efficiency | Yield | Blood Sample | Extraction Time | Hematocrit Level | Final Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [76] | 40 µL | 99.9% | 17.2 ± 1.96 µL | Whole blood | 108 ± 21 s | 70–90% | Plasma separation |

| [77] | 1 mL | 99.9% | 76.7 ± 11.5% | Whole blood | 2 min | 50% | Plasma separation |

| [78] | 5 µL/h | ~100% | NA | Whole blood | NA | NA | Plasma separation by Halbach array |

| [79] | 4 mL | NA | 83.3 ± 1.64% | Whole blood | 100 µL/min | NA | Plasma separation for biomarker analysis |

| [80] | 100 μL | 99.9% | 40 µL | Whole blood | ~8 min | NA | Plasma separation for biochemical analysis |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Tarim, E.A.; Mauk, M.G.; El-Tholoth, M. Emerging Microfluidic Plasma Separation Technologies for Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Moving Beyond Conventional Centrifugation. Biosensors 2026, 16, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010014

Tarim EA, Mauk MG, El-Tholoth M. Emerging Microfluidic Plasma Separation Technologies for Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Moving Beyond Conventional Centrifugation. Biosensors. 2026; 16(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleTarim, Ergun Alperay, Michael G. Mauk, and Mohamed El-Tholoth. 2026. "Emerging Microfluidic Plasma Separation Technologies for Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Moving Beyond Conventional Centrifugation" Biosensors 16, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010014

APA StyleTarim, E. A., Mauk, M. G., & El-Tholoth, M. (2026). Emerging Microfluidic Plasma Separation Technologies for Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Moving Beyond Conventional Centrifugation. Biosensors, 16(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios16010014