Simulation and Optimization of Ballistic-Transport-Induced Avalanche Effects in Two-Dimensional Materials

Abstract

1. Introduction

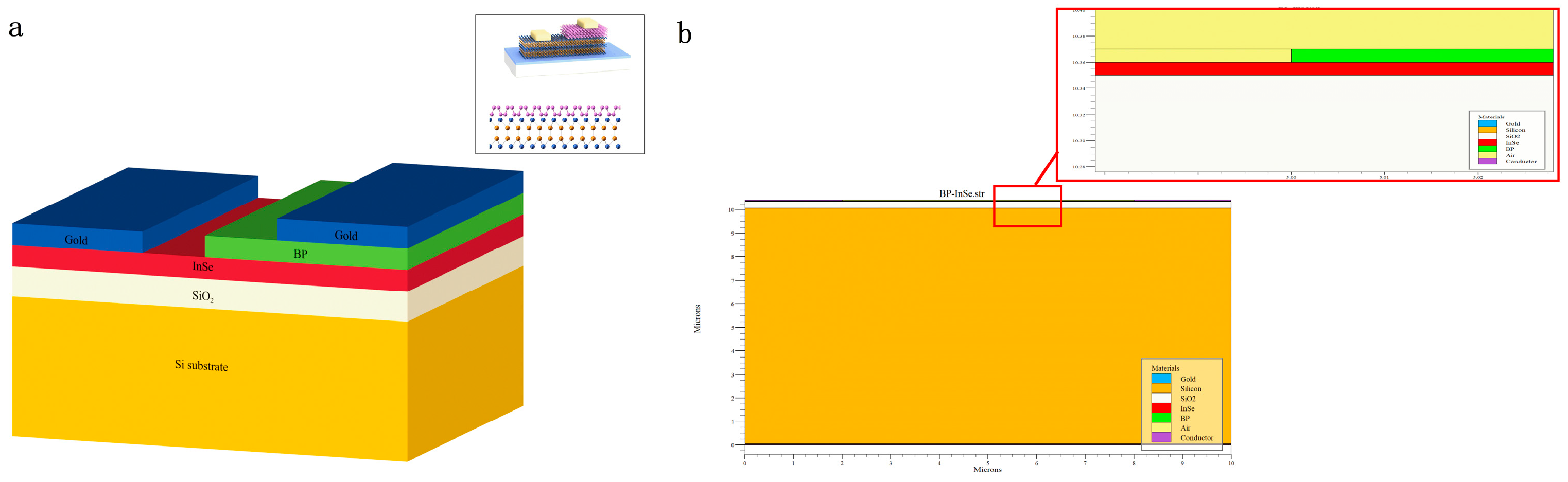

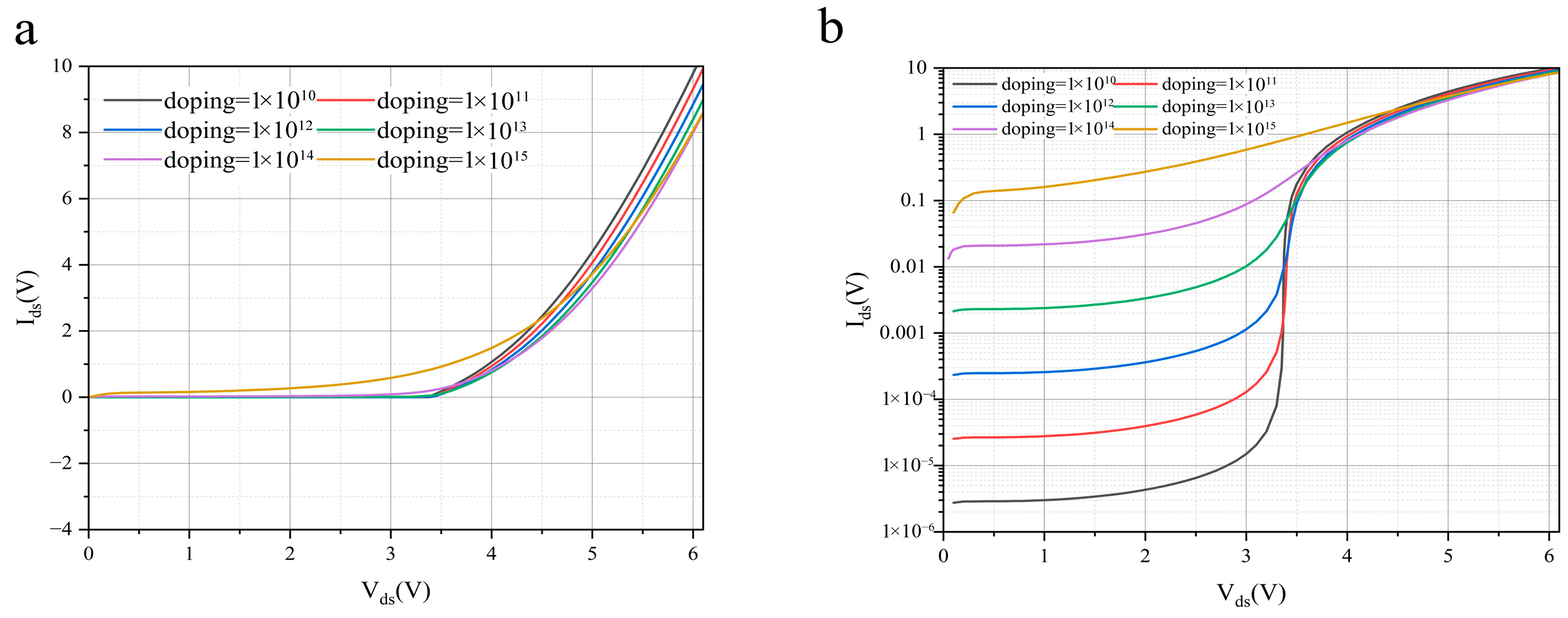

2. Materials and Methods

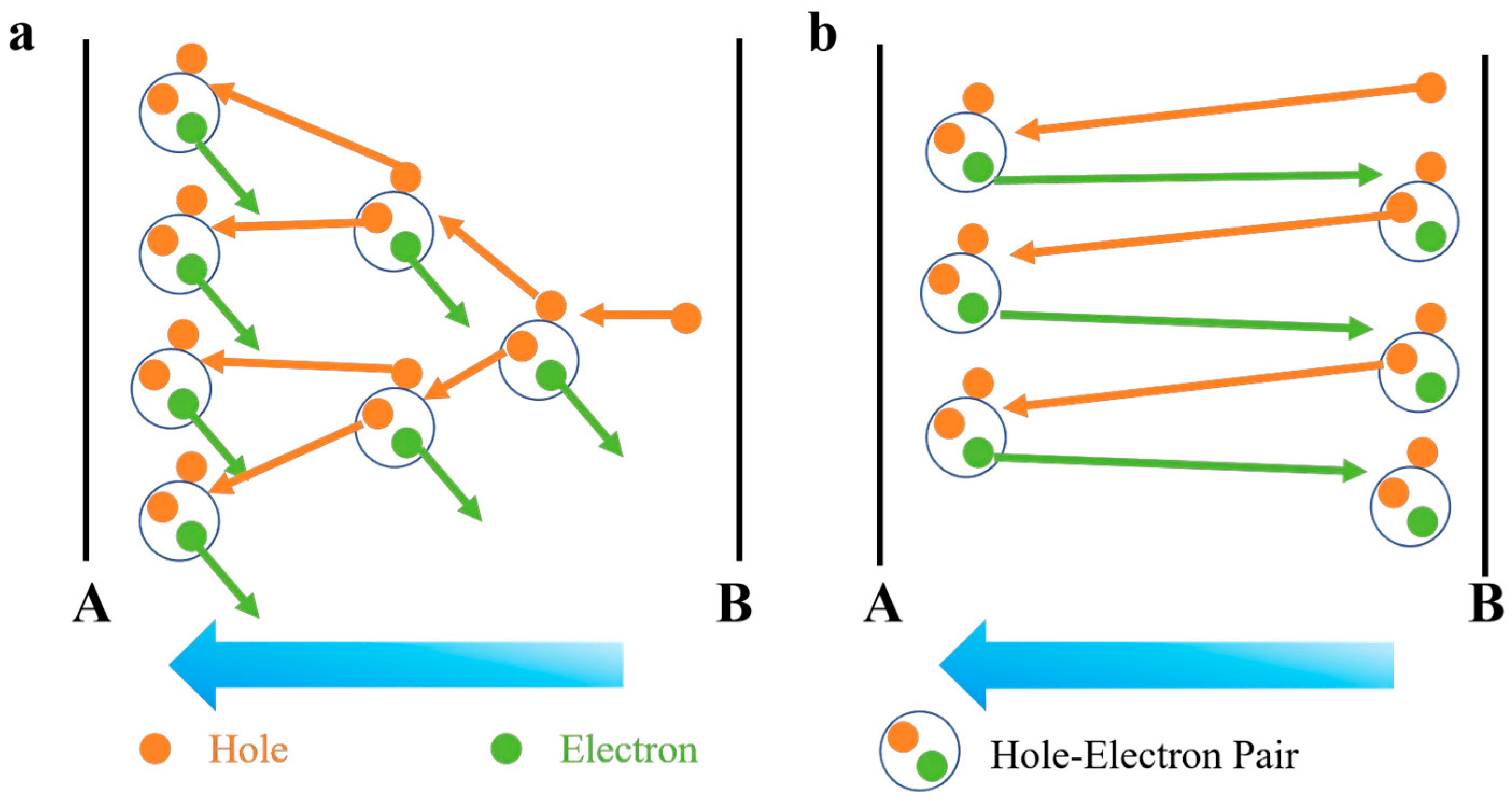

2.1. Ballistic-Transport Avalanche Model

2.2. Material Parameters

| Parameters | BP | InSe |

|---|---|---|

| Band Gap/eV | 0.50 | 1.28 |

| Permittivity | 7.25 | 4.80 |

| Electron mobility/cm2 v−1 s−1 | 150.00 | 100.00 |

| Hole mobility/cm2 v−1 s−1 | 50.00 | 50.00 |

| Effective electronic mass | 0.64 m0 | 0.22 m0 |

| Effective hole quality | 0.71 m0 | 0.75 m0 |

| Electron affinity/eV | 4.00 | 4.20 |

| Doping content/cm−3 | Variable (p-type) | Variable (n-type) |

| Minority carrier lifetime/s | 1 × 10−8 | 1 × 10−9 |

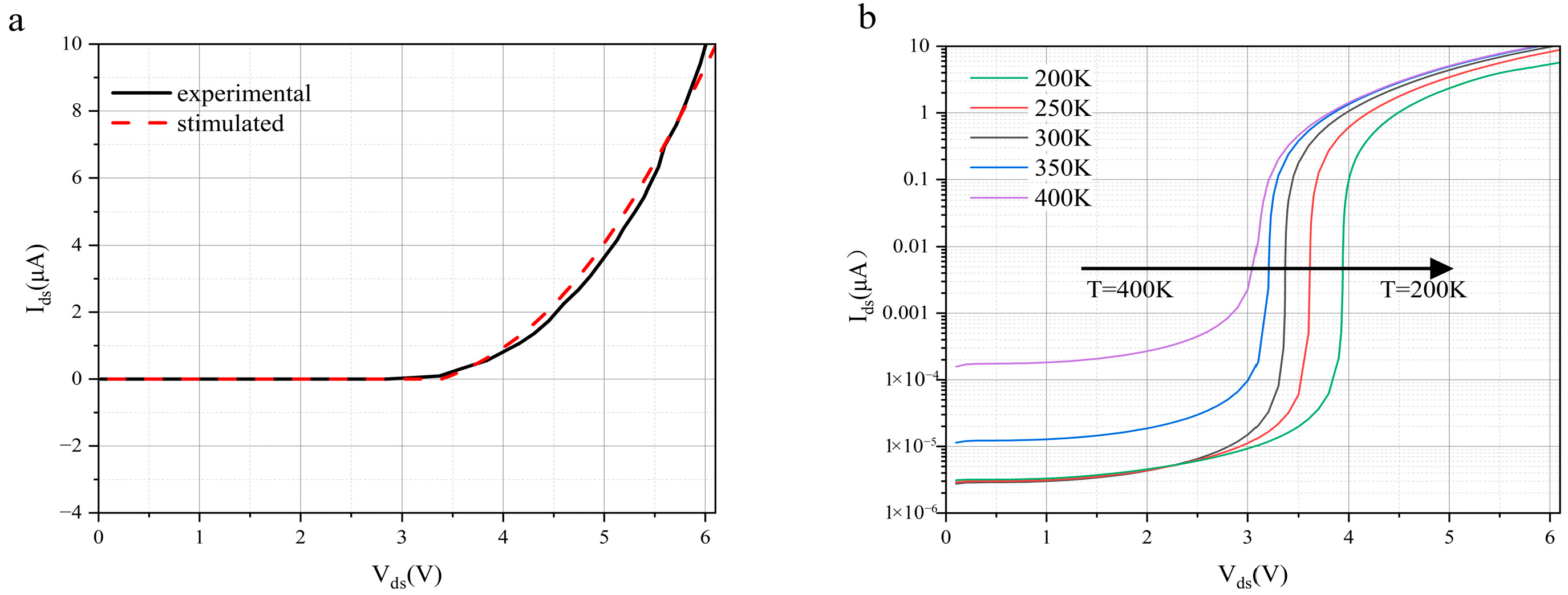

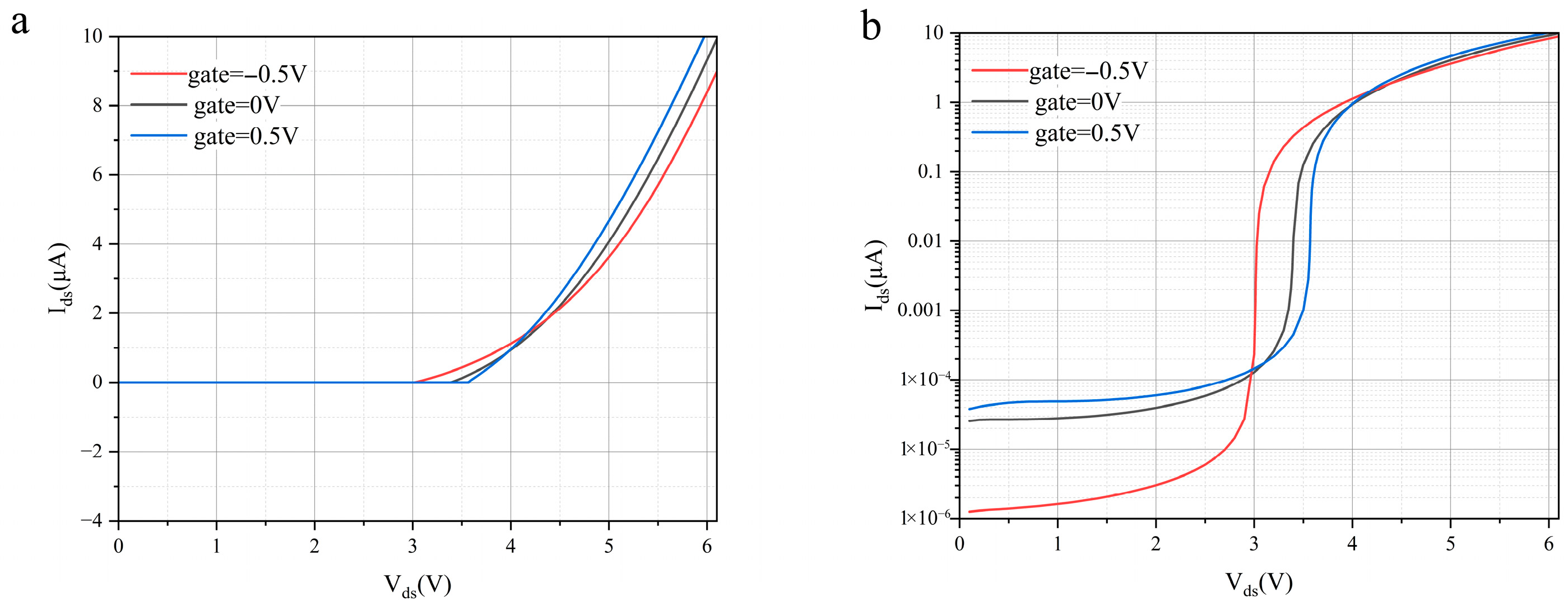

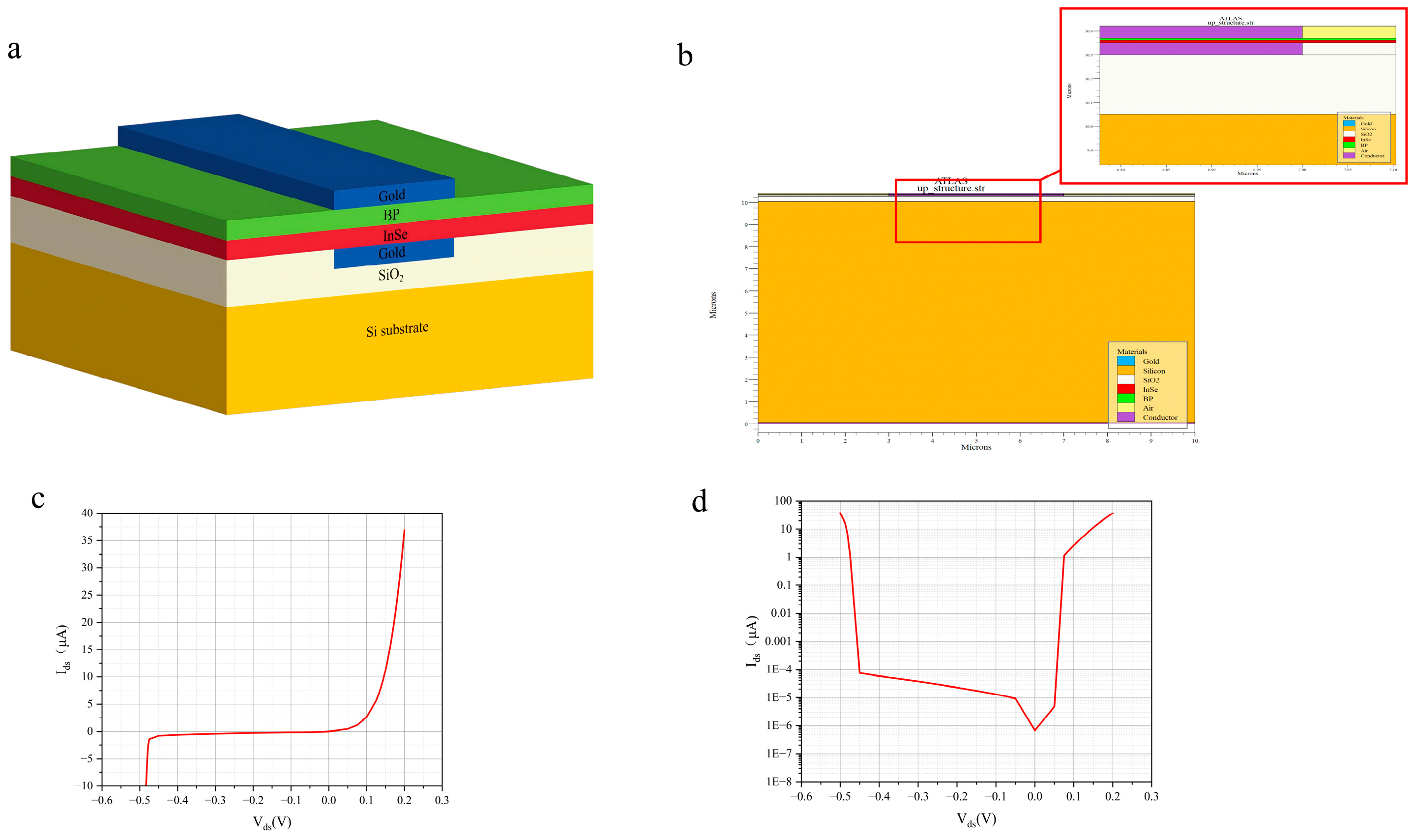

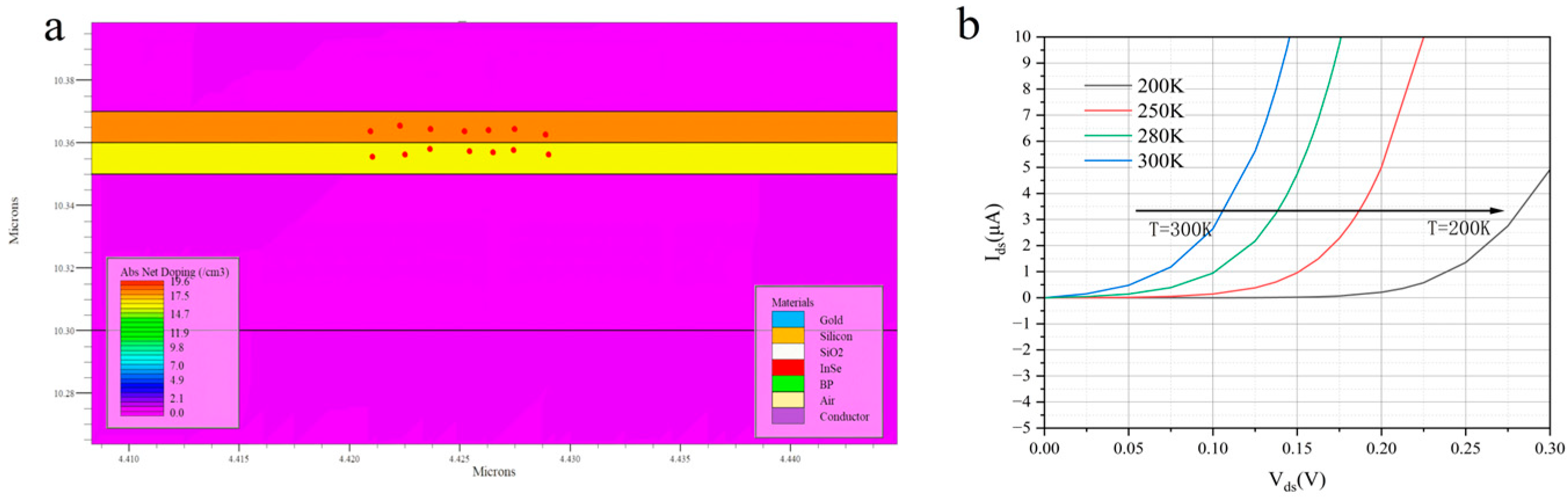

3. Results and Discussion

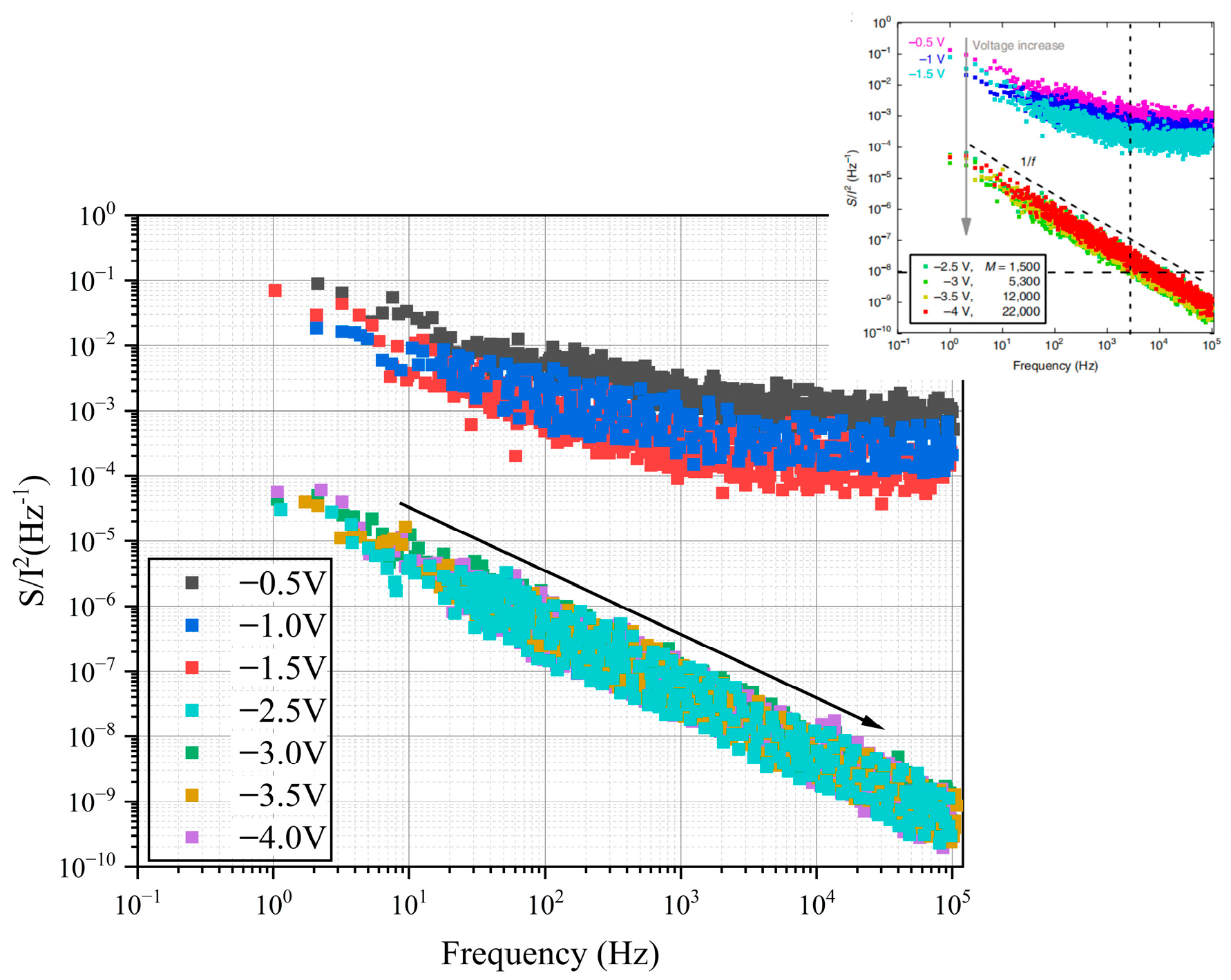

3.1. Discussion and Analysis

3.2. Prediction and Improvement

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Majumder, K.; Rakshit, P.; Das, N. Effect of Submicron Structural Parameters on the Performance of a Multi-Diode CMOS Compatible Silicon Avalanche Photodetector. Semiconductors 2020, 54, 1032–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Zhang, F. Recent Progress on Photomultiplication Type Organic Photodetectors. Laser Photonics Rev. 2019, 13, 1800204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skukan, N.; Grilj, V.; Sudic, I.; Pomorski, M.; Kada, W.; Makino, T.; Kambayashi, Y.; Andoh, Y.; Onoda, S.; Sato, S.; et al. Charge multiplication effect in thin diamond films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016, 109, 043502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blain, T.; Shulyak, V.; Han, I.; Hopkinson, M.; Ng, J.; Tan, C. Low Noise Equivalent Power InAs Avalanche Photodiodes for Infrared Few-Photon Detection. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2024, 71, 3039–3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanitzek, M.; Hack, M.; Schwarz, D.; Schulze, J.; Oehme, M. Low-temperature performance of GeSn-on-Si avalanche photodiodes toward single-photon detection. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2024, 176, 108303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, J.; Song, W.; Wang, P.; Gambin, V.; Huang, Y.; Duan, X. Ultra-Steep Slope Impact Ionization Transistors Based on Graphene/InAs Heterostructures. Small Struct. 2021, 2, 2000039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, B.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Tang, C.; Chen, W.; Cheng, Z.; Zhao, C.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Gan, W.; et al. High drain field impact ionization transistors as ideal switches. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, I.; Park, S.; Hong, K.; Lee, D. Characteristics Measurement in a Deep UV Single Photon Detector Based on a TE-cooled 4H-SiC APD. IEEE Photonics J. 2023, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadfield, R.; Leach, J.; Fleming, F.; Paul, D.; Tan, C.; Ng, J.; Henderson, R.; Buller, G. Single-photon detection for long-range imaging and sensing. Optica 2023, 10, 1124–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Peng, Z.; Tan, C.; Yang, L.; Xu, R.; Wang, Z. Emerging single-photon detection technique for high-performance photodetector. Front. Phys. 2024, 19, 62502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nada, M.; Nakajima, F.; Yoshimatsu, T.; Nakanishi, Y.; Tatsumi, S.; Yamada, Y.; Sano, K.; Matsuzaki, H. High-speed III-V based avalanche photodiodes for optical communications-the forefront and expanding applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 116, 140502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, B.; Ahmed, S.; Xue, X.; Rockwell, A.; Ha, J.; Lee, S.; Liang, B.; Jones, A.; McArthur, J.; Kodati, H.; et al. Temperature Dependence of Avalanche Breakdown of AlGaAsSb and AlInAsSb Avalanche Photodiodes. J. Light. Technol. 2022, 40, 5934–5942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, S.; Hasuike, N.; Kanegae, K.; Nishinaka, H.; Yoshimoto, M. Raman scattering study of photoexcited plasma in GaAsBi/GaAs heterostructures: Influence of carrier confinement on photoluminescence. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2023, 162, 107543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, Y.; Zhai, H.; Wu, Z.; Guo, D.; Dong, X.; Wang, J.; Tang, W.; Kang, J.; Chu, J.; et al. Photomultiplication-Type β-Ga2O3 Solar-Blind Photodetector with Excellent Capability of Weak Signal Detection and Anti-Interference DUV Imaging. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, e01641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masudy-Panah, S.; Moravvej-Farshi, M. An Analytic Approach to Study the Effects of Optical Phonon Scattering Loss on the Characteristics of Avalanche Photodiodes. IEEE J. Quantum Electron. 2010, 46, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, S.; Samiya, M.; Liao, W.; Iqbal, M.; Ishfaq, M.; Ramachandraiah, K.; Ajmal, H.; Ul Haque, H.; Yousuf, S.; Ahmed, Z.; et al. Switching photodiodes based on (2D/3D) PdSe2/Si heterojunctions with a broadband spectral response. J. Mater. Chem. C 2021, 9, 3998–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elahi, E.; Khan, M.; Aziz, J.; Ahsan, U.; Chauhan, P.; Assiri, M.; Sarkar, K.; Asgher, U.; Sofer, Z. Emerging avalanche field-effect transistors based on two-dimensional semiconductor materials and their sensory applications. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 15767–15795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, J.; Yu, F.; Chen, X.; Lu, W.; Li, G. Achieving a Noise Limit with a Few-layer WSe2 Avalanche Photodetector at Room Temperature. Nano Lett. 2024, 24, 13255–13262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martyniuk, P.; Wang, P.; Rogalski, A.; Gu, Y.; Jiang, R.; Wang, F.; Hu, W. Infrared avalanche photodiodes from bulk to 2D materials. Light-Sci. Appl. 2023, 12, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, J.; Wang, C. Avalanche photodetectors based on two-dimensional layered materials. Nano Res. 2021, 14, 1878–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Kang, M.; Fang, Y.; Martyniuk, P.; Wang, H. Avalanche Multiplication in Two-Dimensional Layered Materials: Principles and Applications. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, J.; Kirchner, M.; Wang, H.; Ren, Y.; Lei, W. Two-dimensional heterostructures and their device applications: Progress, challenges and opportunities-review. J. Phys. D-Appl. Phys. 2021, 54, 433001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvaco International. ATLAS User’s Manual; Version 5.22.1.R; Silvaco International: Santa Clara, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Xu, B.; Pei, S.; Zhu, J.; Wen, T.; Jiao, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, M.; Xia, J. Recent progress in 2D van der Waals heterostructures: Fabrication, properties, and applications. Sci. China-Inf. Sci. 2022, 65, 211401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Cao, L.; Ang, Y.; Ang, L.; Zhang, P. Reducing Contact Resistance in Two-Dimensional-Material-Based Electrical Contacts by Roughness Engineering. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2020, 13, 064021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, A.; Ugeda, M.; da Jornada, F.; Qiu, D.; Ruan, W.; Zhang, Y.; Wickenburg, S.; Riss, A.; Lu, J.; Mo, S.; et al. Probing the Role of Interlayer Coupling and Coulomb Interactions on Electronic Structure in Few-Layer MoSe2 Nanostructures. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 2594–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, S.; Wang, F.; Zhang, G.; Song, C.; Lei, Y.; Xing, Q.; Wang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xie, Y.; et al. From Anomalous to Normal: Temperature Dependence of the Band Gap in Two-Dimensional Black Phosphorus. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 125, 156802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, Z.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y. Anisotropic charged impurity-limited carrier mobility in monolayer phosphorene. J. Appl. Phys. 2014, 116, 214505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Bartolomeo, A.; Kumar, A.; Durante, O.; Sessa, A.; Faella, E.; Viscardi, L.; Intonti, K.; Giubileo, F.; Martucciello, N.; Romano, P.; et al. Temperature-dependent photoconductivity in two-dimensional MoS2 transistors. Mater. Today Nano 2023, 24, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duman, S.; Gurbulak, B.; Turut, A. Temperature-dependent optical absorption measurements and Schottky contact behavior in layered semiconductor n-type InSe(:Sn). Appl. Surf. Sci. 2007, 253, 3899–3905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Liu, L.; Wen, B.; Zhang, X. Monolayer InSe photodetector with strong anisotropy and surface-bound excitons. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 6075–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Tian, R.; Luo, X.; Yin, R.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, J.; Wang, X.; Gan, X. Photovoltaic effects in reconfigurable heterostructured black phosphorus transistors. Chin. Phys. B 2018, 27, 128502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Kong, X.; Hu, Z.; Yang, F.; Ji, W. High-mobility transport anisotropy and linear dichroism in few-layer black phosphorus. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, V.; Grigoriev, A.; Ahuja, R. Rectifying behavior in twisted bilayer black phosphorus nanojunctions mediated through intrinsic anisotropy. Nanoscale Adv. 2020, 2, 1493–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Cheng, H.; Lai, W.; Sankar, R.; Chang, C.; Lin, K. Ultrafast carrier dynamics and layer-dependent carrier recombination rate in InSe. Nanoscale 2023, 15, 3169–3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zereshki, P.; Wei, Y.; Ceballos, F.; Bellus, M.; Lane, S.; Pan, S.; Long, R.; Zhao, H. Photocarrier dynamics in monolayer phosphorene and bulk black phosphorus. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 11307–11313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, Y. Unusual phonon behavior and ultra-low thermal conductance of monolayer InSe. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Peng, J.; Yang, S.; Liu, D.; Xiao, Y.; Cao, G. Lifetime and nonlinearity of modulated surface plasmon for black phosphorus sensing application. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 18878–18891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Liu, C.; Zhao, J.; Yao, Y. Monolayer group-III monochalcogenides by oxygen functionalization: A promising class of two-dimensional topological insulators. npj Quantum Mater. 2018, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohier, T.; Gibertini, M.; Marzari, N. Profiling novel high-conductivity 2D semiconductors. 2D Mater. 2021, 8, 015025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

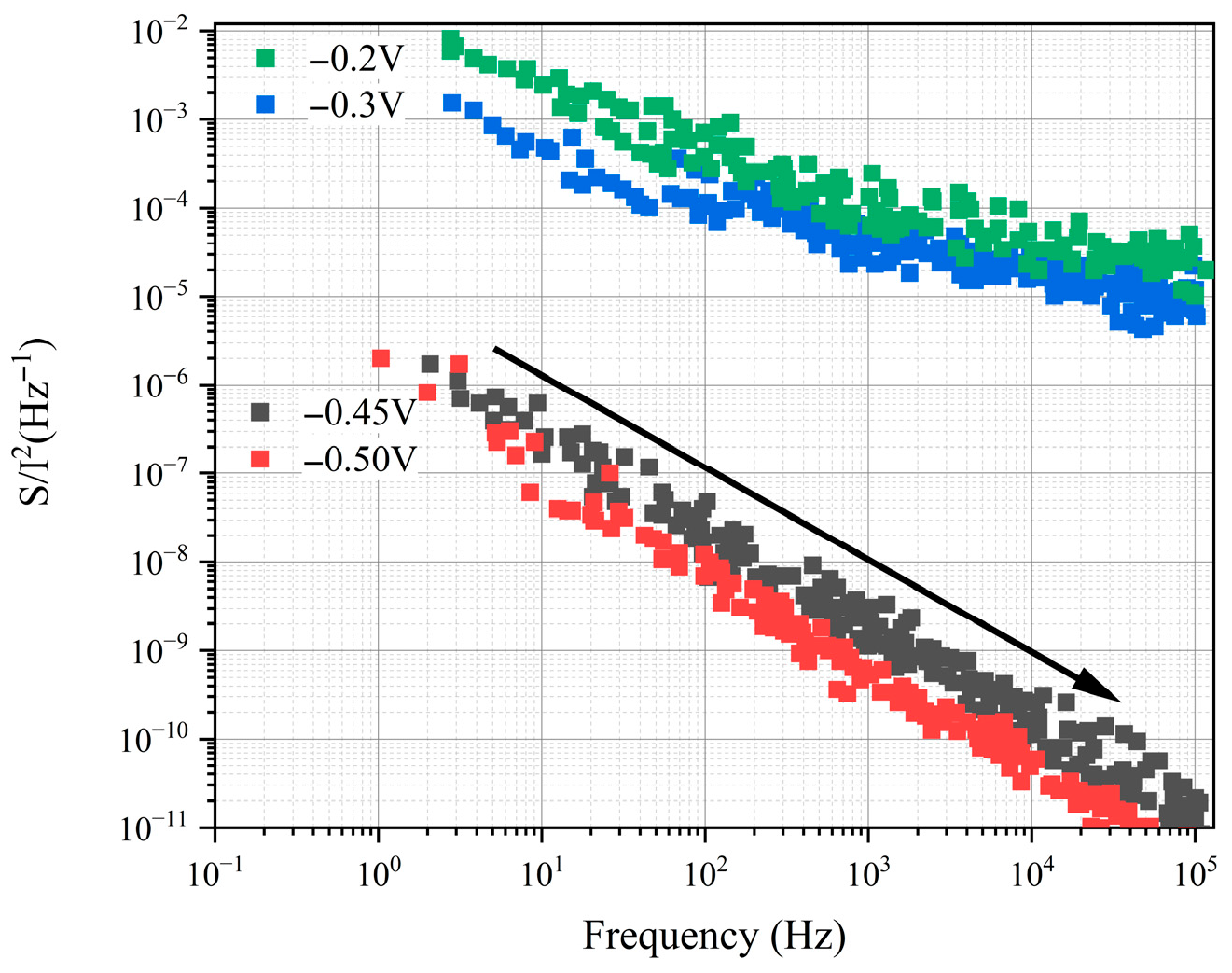

- Gao, A.; Lai, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Zeng, J.; Yu, G.; Wang, N.; Chen, W.; Cao, T.; Hu, W.; et al. Observation of ballistic avalanche phenomena in nanoscale vertical InSe/BP heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2019, 14, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emami, F.; Tehrani, M. Noise in Avalanche Photodiodes. In Proceedings of the 12th WSEAS International Conference on Communications, Heraklion, Greece, 23–25 July 2008; pp. 327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, X.; Wang, R.; Tang, Y. Excess noise factor measurement for low-noise high-speed avalanche photodiodes. Phys. Scr. 2023, 9, 1055178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Yeon, E.; Hwang, D. Recent Progress in 2D Heterostructures for High-Performance Photodetectors and Their Applications. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2025, 13, 2403412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, M.; Guo, Z.; Chen, X.; Ma, X.; Zhou, L. Surface/Interface Engineering for Constructing Advanced Nanostructured Photodetectors with Improved Performance: A Brief Review. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Z.; Wang, W.; Zhu, P. All-semiconductor plasmonic type-II superlattice detector with dual-band absorption enhancement. Opt. Eng. 2024, 63, 107104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Liang, J.; Cai, H.; Li, W.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Tang, X.; Zheng, W. Interface Engineering of Rare-Earth Oxide-GaN Heterojunction for Improving Vacuum-Ultraviolet Photodetection. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2025, 72, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Device/Structure/Material | R (A/W) | RT (ms) | λ (nm) | IDark (A) | EQE | NPD (W−1) | M | T (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BP/InSe APD | 80 | -- | 4000 | -- | 248 | -- | 104–105 | 10–180 |

| BP APD | 130 | -- | 500–1100 | 2 × 10−6 | 310 | 6.5 × 107 | 7 | 300 |

| InSe APD | 11,000 | 1 | 405–785 | 5 × 10−9 | -- | 2.5 × 102 | 500 | -- |

| MoTe2-WS2-MoTe2 APD | 6.02 | 475 | 400–700 | 9.3 × 10−11 | 14.1 | 6.47 × 109 | 587 | 295 |

| Si | 0.5–1.0 | 10−6 | 400–1100 | 10−15–10−12 | 50–80 | -- | 50–100 | 300 |

| Ge | 0.7–1.2 | 10−5 | 800–1800 | 10−15–10−12 | 40–70 | -- | 40–80 | 300 |

| InGaAs | 0.9–1.5 | 10−6 | 900–1700 | 10−18–10−13 | 70–90 | -- | 30–50 | 300 |

| HgCdTe | 0.5–1.2 | 10−6 | 2000–18,000 | 10−18–10−12 | 30–70 | -- | 100–200 | 77 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Wu, H.; Li, T.; Cheng, B.; Luo, J.; Jiang, R.; Cai, M.; Huang, S.; Song, H. Simulation and Optimization of Ballistic-Transport-Induced Avalanche Effects in Two-Dimensional Materials. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16030154

Wang H, Zhang W, Wu H, Li T, Cheng B, Luo J, Jiang R, Cai M, Huang S, Song H. Simulation and Optimization of Ballistic-Transport-Induced Avalanche Effects in Two-Dimensional Materials. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(3):154. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16030154

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Haipeng, Wei Zhang, Han Wu, Tong Li, Beitong Cheng, Jieping Luo, Ruomei Jiang, Mengke Cai, Shuai Huang, and Haizhi Song. 2026. "Simulation and Optimization of Ballistic-Transport-Induced Avalanche Effects in Two-Dimensional Materials" Nanomaterials 16, no. 3: 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16030154

APA StyleWang, H., Zhang, W., Wu, H., Li, T., Cheng, B., Luo, J., Jiang, R., Cai, M., Huang, S., & Song, H. (2026). Simulation and Optimization of Ballistic-Transport-Induced Avalanche Effects in Two-Dimensional Materials. Nanomaterials, 16(3), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16030154