3. Results and Discussion

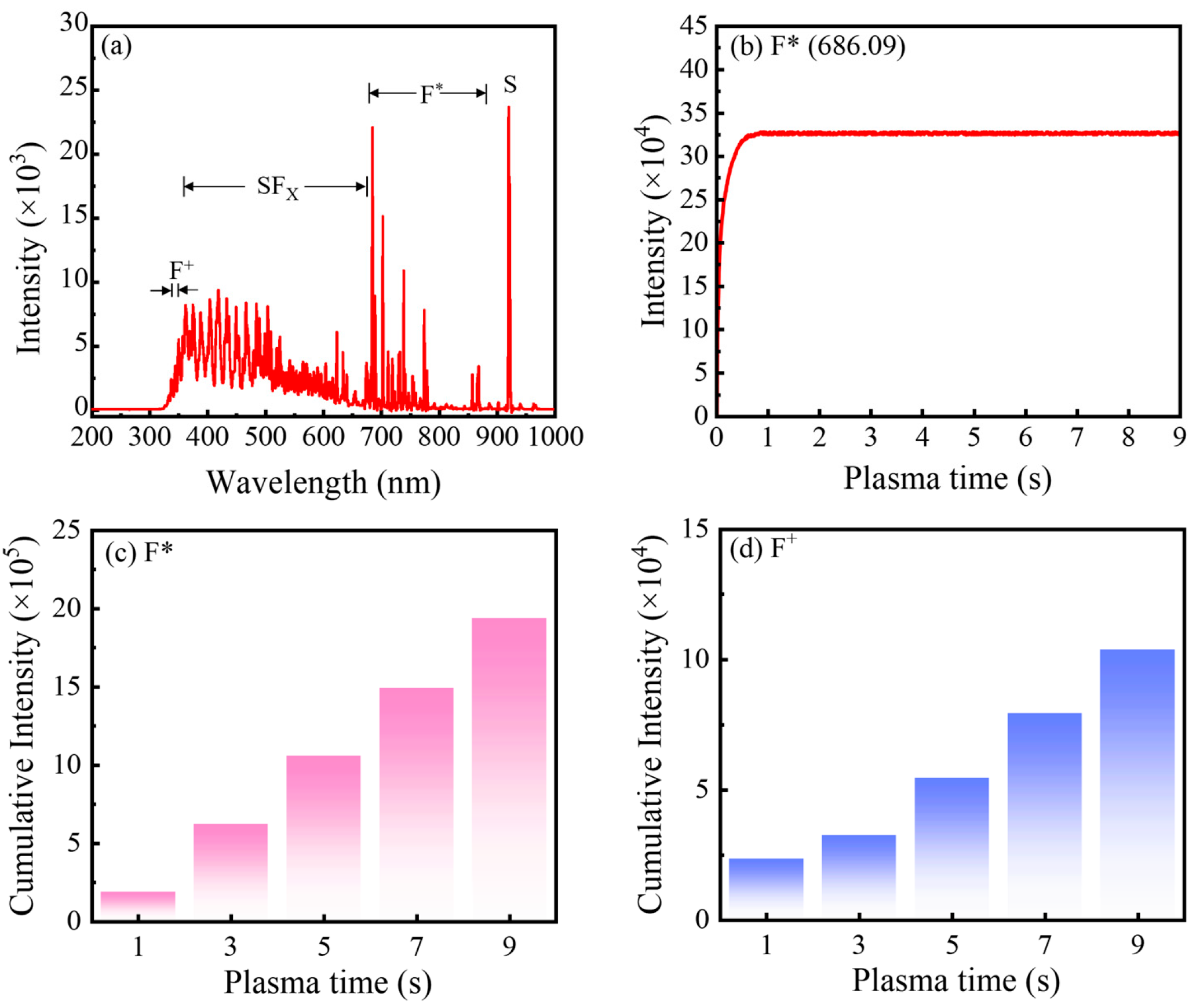

Figure 1a shows the optical emission spectra (OES) of the SF

6 plasma used in this work. Under plasma discharge, SF

6 molecules are dissociated by electron-impact collisions, and a fraction of the resulting fragments are excited to higher electronic states. Their subsequent relaxation to lower energy levels emits photons that are captured by OES. The broad features observed at 350–670, 670–870, and 921 nm are attributed to SF

x (1 ≤ x ≤ 5), F*, and S species, respectively [

16,

18]. In addition, the peaks at 340–350 nm are assigned to F

+ species, as confirmed by comparison with the NIST database [

19]. To assess the temporal stability of the SF

6 plasma during the pulse, the intensity of the most prominent fluorine emission line (F* at 686.09 nm) was monitored as a function of SF

6 plasma pulse time. As shown in

Figure 1b, the F* intensity increases initially and then reaches a plateau, remaining essentially constant from 1 s to 9 s. This behavior directly evidences a stable and reproducible plasma discharge over this time window, implying a well-controlled and repeatable flux of reactive species impinging on the substrate during PEALD.

Figure 1c,d present the integrated emission intensities of F* (670–870 nm) and F

+ (340–350 nm) as a function of SF

6 plasma pulse time. Both species exhibit a nearly linear increase in accumulated intensity with increasing pulse time, reflecting the progressively larger total dose of fluorine-containing species delivered to the surface. The neutral fluorine radicals (F*) are particularly critical, as they react with the TMA-derived methyl-terminated surface to efficiently remove CH

3 ligands and form Al–F bonds, thereby enabling self-limiting fluorination. In contrast, although a modest concentration of F

+ has limited impact on film growth, an excessive ion flux can strongly bombard the growing surface, break bonds, and introduce ion-induced damage. This ultimately degrades film quality, underscoring the need to carefully balance neutral radical supply against ion bombardment when optimizing the plasma pulse time for high-quality AlF

3 PEALD films.

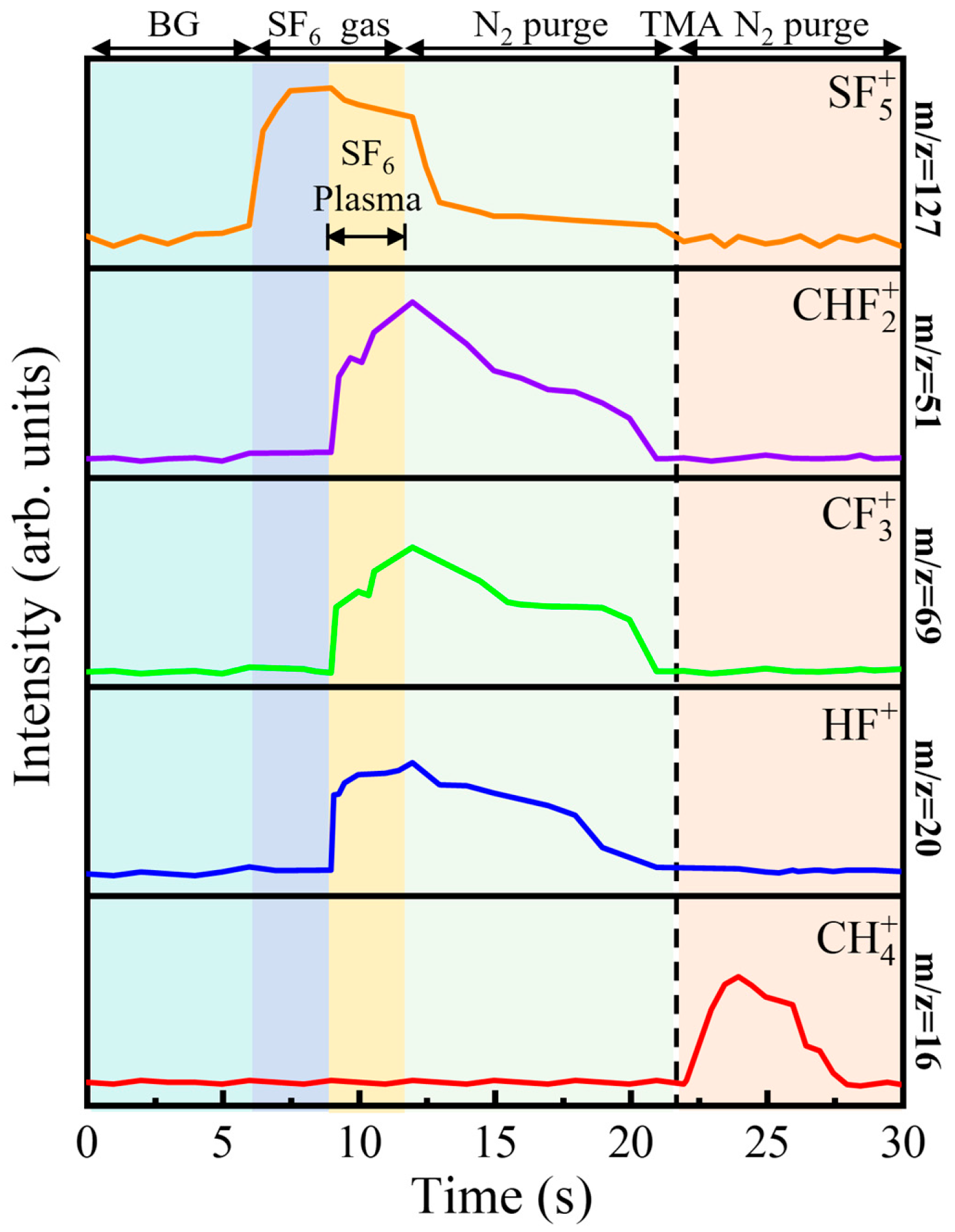

Figure 2 presents the temporal evolution of key mass-to-charge (

m/

z) signals, monitored by in situ RGA, thereby resolving the sequence of chemical events within a single PEALD cycle. At the beginning of the cycle, all tracked signals remain at a stable, low-intensity background level, indicating an inert gas-phase environment. The first half-reaction is initiated at 6 s by igniting the SF

6 plasma. The sharp rise in the signal at

m/

z = 127, attributed to SF

5+—the principal fragment of SF

6 [

16,

20,

21]—confirms effective precursor dissociation and the rapid generation of fluorine-containing plasma species. Simultaneously, a series of reaction byproducts emerges: carbon tetrafluoride (CF

4, identified via its dominant fragment CF

3+ at

m/

z = 69 [

16]), trifluoromethane (CHF

3, via CF

2H

+ at

m/

z = 51 [

16]), and hydrogen fluoride (HF,

m/

z = 20 [

14,

16,

22]). The concurrent appearance of CF

4 and CHF

3 is particularly revealing. It indicates that the removal of surface methyl groups proceeds via two parallel fluorination pathways. The formation of CF

4 corresponds to a complete fluorination route, in which all C–H bonds are replaced by C–F bonds under the action of the highly reactive, fluorine-rich plasma. In contrast, the formation of CHF

3 reflects a reaction pathway yielding a volatile species in which one C–H bond remains intact. It is crucial to note that both CF

4 and CHF

3 serve as effective elimination routes for removing carbon from the surface. Analysis of the RGA signal intensities reveals that these two pathways operate in parallel with a relatively constant ratio throughout the plasma pulse (1–9 s). This stability confirms that the reaction mechanism itself does not change over time. The completeness of ligand removal is strictly governed by the cumulative reaction time. After the RF power is switched off at 9 s, a 10 s purge step efficiently removes the gaseous reactants and byproducts, as evidenced by all mass signals returning to their initial background levels. The second half-reaction begins at 18 s with the introduction of the TMA pulse. This step is marked by a pronounced increase in the signal at

m/

z = 16, corresponding to CH

4, which is observed as the sole volatile byproduct [

15,

16,

23]. The exclusive formation of methane is a crucial mechanistic signature: it implies that the preceding plasma step not only strips the methyl ligands but also leaves the surface terminated with hydrogen-containing fluorinated species. These surface—F(H) groups then react cleanly with incoming TMA to produce CH

4, consistent with a well-defined, self-limiting ligand-exchange reaction. Together, the RGA data in

Figure 2 provide a coherent, time-resolved picture of the PEALD cycle, directly linking plasma-driven fluorination chemistry to the formation of a protonated fluorine–terminated surface that underpins the subsequent AlF

3 growth.

Based on the in situ OES and RGA results, a detailed surface reaction mechanism for the PEALD of AlF

3 is proposed, as schematically illustrated in

Figure 3. In the absence of direct vibrational spectroscopy, the RGA data indicates that the deposition proceeds on a hydrogen-terminated fluorinated surface (tentatively s-FH). This is supported by the consistent detection of CH

4 during the TMA half-cycles. Residual OH groups or hydrogen on the glass substrate could theoretically generate CH

4, but this influence is restricted to the very first few ALD cycles. Once the growing AlF

3 film fully covers the substrate, the CH

4 generation observed during steady-state growth implies that FH ligands are continuously regenerated on the film surface during the SF

6 plasma step. This regeneration mechanism aligns with prior reports on ALD AlF

3, where such a termination is considered essential for the reaction with TMA [

14,

15]. On this basis, the self-limiting TMA half-reaction can be plausibly written as:

where s denotes the substrate surface. After the TMA pulse and subsequent purge, residual gas-phase species and CH

4 are removed, leaving the surface terminated with Al(CH

3)

2 groups. The second half-reaction involves exposing this Al(CH

3)

2-terminated surface to the SF

6 plasma. The completeness of this step—and thus the resulting film quality—depends critically on the plasma pulse time, leading to three distinct regimes, as depicted in

Figure 3. (i) Short plasma exposure (t = 1 s). For a short SF

6 plasma pulse, the total dose of fluorine radicals and energetic ions is insufficient to drive ligand exchange to completion across the entire surface. As a result, the removal of carbon-containing ligands is incomplete, yielding a mixed surface that contains fully converted AlF

3 alongside residual carbonaceous fragments. This can be summarized as:

where F* denotes neutral fluorine radicals. In this regime, the process must also regenerate the active s-FH sites required for the next cycle. This regeneration is likely driven by surface protonation facilitated by the abundant HF generated in situ, as suggested by the HF RGA signal. (ii) Self-limiting PEALD window (3 ≤ t < 7 s). When the plasma pulse time is sufficiently long (e.g., 3–5 s), the F* dose becomes adequate to fully remove the methyl ligands and to completely fluorinate the surface, forming a dense, stoichiometric AlF

3 layer. This regime is consistent with the simultaneous detection of CF

4 (via its

m/

z = 69 fragment) and CHF

3 (

m/

z = 51), reflecting the coexistence of two parallel volatile pathways (CF

4 and CHF

3) that together ensure exhaustive ligand removal. The overall reaction can be written as:

Within this window, minor variations with pulse time still exist. For example, as the exposure is extended from 3 s to 5 s, a slightly higher ion flux may begin to introduce a small degree of structural disorder. Nevertheless, the films remain chemically pure and highly dense, corresponding to the optimal growth regime identified experimentally. (iii) Excessive plasma exposure (7 ≤ t ≤ 9 s). For longer plasma pulses, the surface is subjected to substantial bombardment by a high flux of F

+ ions, while the chemical fluorination reaction is already complete. In this overexposed regime, the dominant effect shifts from chemistry to ion-driven physics: sustained ion bombardment can induce bond breaking, generate defects, increase surface roughness, and reduce film density through sputtering or microstructural damage. This can be conceptually expressed as:

where s-F-Al-F

x denotes a damaged, sub-stoichiometric Al-F

x environment. Although direct ion flux measurements were not performed, the transition to an ion-driven regime is rationalized by the specific configuration of the remote ICP source. Based on literature for similar remote ICP reactors, the average ion energy is expected to be comparable to 9 ± 1 eV, with an ion flux of approximately 10

13 cm

−2s

−1 [

24]. Consequently, the critical factor is not the single-particle energy but rather the cumulative ion-energy dose defined as the product of mean energy, flux, and time. As evidenced by the linear rise in F

+ emission intensity in

Figure 1d, the total energy delivered to the surface increases continuously with pulse duration. In this work, the fluorination reaction reaches chemical saturation at 3–5 s. Beyond this saturation point, the sustained bombardment at 7–9 s provides a high cumulative dose that disrupts the Al-F bonding equilibrium. This promotes the preferential sputtering (or selective stimulated desorption) of the lighter fluorine atoms, which are more susceptible to energy-induced removal than Al atoms. This shift from self-limiting growth to energy-induced fluorine loss accounts for the decline in growth rate, the fluorine deficiency, and the increased surface roughness observed in the following GPC, XPS, and AFM characterizations. The fluorine deficiency corresponds to the generation of point defects, specifically anion vacancies or unsaturated metal sites within the lattice. Comparative analysis with well-studied fluorides offers critical insights into the potential consequences of these defects. For instance, Romanova et al. [

25] demonstrated that defect sites in CaF

2 serve as charge traps that fundamentally alter dielectric behavior. Similarly, Skriabin et al. [

26] showed that radiation-induced surface defects in MgF

2 can facilitate oxygen diffusion, thereby accelerating surface degradation and oxidation. Drawing from these findings, it can be predicted that the F-deficient PEALD AlF

3 films generated in the excessive exposed regime are likely susceptible to similar failure modes, where anion vacancies could act as charge traps or pathways for post-deposition oxidation, ultimately compromising optical stability. Taken together, the mechanism reveals that an optimal plasma pulse time must balance two competing requirements: supplying sufficient F* radicals to ensure complete ligand removal and full fluorination, while avoiding excessive F

+ bombardment that compromises structural integrity. This framework provides a clear mechanistic basis for the subsequent correlation between plasma pulse time, film composition and microstructure, and ultimately the optical performance of the AlF

3 coatings. To investigate the influence of SF

6 plasma pulse time on the AlF

3 deposition, the growth characteristics are studied.

Figure 4a displays the film thickness as a function of the number of PEALD cycles for various plasma pulse times. For all conditions, the film thickness exhibits a good linear dependence on the number of cycles. This linearity confirms that each cycle contributes a consistent and repeatable amount of material, which is a hallmark of a self-limiting deposition process [

13,

27]. To rigorously validate the ideal ALD characteristics of the developed process, the saturation behavior of the precursor half-reaction and the temperature dependence are evaluated, as detailed in

Figure S1 (Supporting Information). The GPC remains constant for TMA pulse times exceeding 0.1 s, confirming that the precursor adsorption is self-limiting. Furthermore, the growth rate exhibits a stable plateau across a substrate temperature range of 200–300 °C, establishing an ALD temperature window. These results, combined with the strict linear relationship between film thickness and cycle number shown in

Figure 4a, unequivocally classify the process as true ALD. The GPC was extracted from the slope of these linear fits, and the results are plotted against the plasma pulse time in

Figure 4b. The GPC plot provides compelling quantitative evidence for the three reaction regimes hypothesized previously. At t = 1 s, the GPC is suppressed to 0.91 ± 0.03 Å/cycle. This confirms incomplete surface reactions and thus a reduced growth rate, as postulated. As t = 3 and 5 s, the GPC rises to a stable plateau of approximately (1.20 ± 0.02)–(1.30 ± 0.02) Å/cycle. This distinct saturation behavior defines the ALD window, in which the plasma dose is sufficient for complete chemical reactions. For longer exposures of t = 7 and 9 s, a clear decrease in GPC to (0.90 ± 0.02) and (0.85 ± 0.02)Å/cycle, respectively, is observed. This trend strongly supports the existence of a competing soft-etching or sputtering effect caused by prolonged ion bombardment, which becomes significant after chemical saturation is achieved.

In

Figure 5a, the XPS survey spectra for AlF

3 films grown with plasma pulse times between 1 and 9 s are dominated by intense Al 2p/2s and F 1s/F KLL features, while C 1s and O 1s peaks remain barely above the detection limit. This immediately points to a highly fluorinated aluminum matrix with only trace levels of extrinsic impurities. Quantitative analysis of the high-resolution spectra, summarized in

Figure 5b, shows that the F/Al atomic ratio follows a pronounced non-monotonic dependence on plasma pulse time. Starting from a sub-stoichiometric value of 2.55 ± 0.03 at 1 s, the ratio increases to a maximum of 2.94 ± 0.04 at 3 s. The small standard deviation derived from three independent runs demonstrates high process reproducibility. Considering the typical XPS quantification uncertainty of ~10% [

28], the measured value is experimentally indistinguishable from the ideal stoichiometric ratio of 3.00. This confirms the formation of fully fluorinated AlF

3. The ratio then gradually decreases to 2.48 ± 0.04 at 9 s. This evolution closely tracks the GPC behavior: the initially low ratio reflects incomplete fluorination under insufficient plasma exposure, the peak at 3 s marks the condition of most efficient fluorine incorporation within the self-limiting PEALD window, and the subsequent decline at longer pulses is consistent with preferential sputtering of the lighter fluorine atoms during prolonged ion bombardment, yielding an increasingly Al-rich film. For the impurity profiles, carbon serving as a direct probe of TMA ligand removal is strongly elevated at short plasma exposure: at 1 s, the carbon content reaches 3.47 at.%, indicating a substantial population of residual carbonaceous fragments. This high impurity level aligns with the kinetic limitation suggested by the RGA data. Since the CF

4 and CHF

3 removal routes operate at a constant ratio, the residual carbon at short pulse times is not due to a shift in reaction pathway, but because the short plasma duration is insufficient to convert all surface methyl ligands into these volatile byproducts. When the plasma pulse is extended to 3 s, the carbon concentration collapses to ~0.3 at.% and remains at this low level for all longer exposures, demonstrating that a 3 s plasma step is sufficient to fully strip the organic ligands. Oxygen levels are consistently below 0.56 at.% across all conditions, underscoring the robustness of the oxygen-free PEALD chemistry. It is noted that hydrogen cannot be quantified by XPS, and since complementary techniques such as elastic recoil detection analysis or secondary ion mass spectrometry are not performed, the specific hydrogen content in these films remains an assumption that is not directly verified in this study. Nevertheless, the presence of hydrogen is chemically deduced from the RGA data, where the exclusive formation of methane necessitates a hydrogen source on the surface. Consistent with this observation, literature on similar PEALD AlF

3 processes explicitly reports hydrogen concentrations of ~1.7 at.% [

15], suggesting that a comparable trace incorporation is likely present in our films. The evolution of fluorine bonding is further clarified in

Figure 5c, where the F 1s core-level spectra are deconvoluted into two components: a dominant peak at ~685.5 eV attributed to F-Al bonds and a weaker shoulder at ~687.0 eV assigned to F–C species [

10,

27]. The fraction of the F-Al component in the total F 1s signal mirrors the trends derived from the elemental analysis. At 1 s, the reduced F-Al fraction reflects incomplete surface reactions and a significant contribution from residual carbonaceous species, consistent with the mechanism described by Equation (2). Under the optimal plasma exposure, the F-Al fraction increases to ~94.6%, indicating that fluorine radicals efficiently convert methyl groups into volatile CF

4 and CHF

3 byproducts and drive the surface toward a fully fluorinated AlF

3 network. Collectively, the XPS results in

Figure 5a–c provide chemically resolved confirmation that a 3 s plasma pulse defines the optimal PEALD window, balancing complete ligand removal and fluorination against the onset of ion-induced fluorine depletion at longer exposures.

In

Figure 6, the GIXRD patterns of the AlF

3 films deposited with different plasma pulse times show no sharp Bragg reflections, only broad diffuse features, confirming that all films are amorphous. Such an amorphous structure is highly advantageous for antireflective applications because it naturally suppresses grain-boundary formation and associated surface corrugation. In contrast to polycrystalline coatings, which often exhibit pronounced grain boundaries and faceted surfaces, these amorphous AlF

3 layers can develop an exceptionally smooth interface. The resulting reduction in surface scattering is expected to enhance optical transmittance and is therefore fully consistent with the excellent antireflection performance observed for these films [

14,

29].

In

Figure 7a–e, AFM images reveal a pronounced dependence of surface morphology on plasma pulse time. Among all conditions, a 3 s plasma pulse produces the smoothest surface, whereas longer pulses (particularly 9 s) lead to visibly roughened topography. The corresponding RMS roughness values are summarized in

Figure 7f. The minimum RMS roughness of 0.24 ± 0.03 nm is obtained at 3 s, coinciding with the saturation of the surface reactions. Such an exceptionally smooth surface is crucial for high-performance antireflective coatings, as it minimizes scattering losses and thus supports high optical transmittance. When the plasma exposure is further extended, the RMS roughness increases markedly, reaching 1.67 ± 0.03 nm at 9 s. This pronounced roughening is a direct morphological consequence of excessive plasma bombardment: once the chemical conversion is complete, continued ion impact effectively transitions to physical etching, damaging the film and introducing nanoscale height fluctuations. These features inherently degrade the antireflective properties by enhancing scattering and haze. The close correspondence between the reaction-saturation point (3 s) and the morphological optimum provides strong physical support for the proposed mechanistic picture and underscores the need to balance sufficient radical/ion flux against plasma-induced damage when optimizing PEALD processes for optical coatings.

In

Figure 8, the wavelength-dependent refractive index spectra of the AlF

3 films are compared with that of bare glass, which exhibits a refractive index of ~1.50–1.53 across the visible range. The film deposited with a 3 s plasma pulse time shows the lowest refractive index over the entire spectral window, reaching values as low as 1.35 at 550–800 nm. This ultralow index is characteristic of a high-quality AlF

3 layer and is fully consistent with the optimal composition and morphology identified above. As the plasma pulse time deviates from 3 s, the refractive index systematically increases. In particular, films grown with longer pulses (5–9 s) display progressively higher indices, which can be ascribed to plasma-induced damage and fluorine depletion, leading to a more Al-rich, higher-index network. Because a low refractive index is essential for efficient antireflection, the AlF

3 film obtained at a 3 s plasma pulse clearly provides the most favorable optical response and is therefore selected for detailed antireflective performance evaluation.

To synthesize the experimental findings presented above,

Table 2 provides a comprehensive summary of the three distinct kinetic regimes governed by the plasma pulse time. This tabulated overview explicitly links the real-time plasma diagnostics and surface reaction pathways to the resulting film properties. The optimal process window (Regime II) represents a critical balance where the plasma dose is sufficient to drive complete ligand exchange to high purity and stoichiometry while remaining moderate enough to prevent the ion-induced damage and roughening observed in the overexposed regime (Regime III).

In

Figure 9a, the antireflective performance of the optimized PEALD AlF

3 film grown with a 3 s plasma pulse is evaluated on glass substrates with a film thickness of 110 nm. The bare glass exhibits an average transmittance of ~(91.5 ± 0.2)%, limited by reflection losses of ~4–5% at each air/glass interface, in good agreement with Fresnel’s equations [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Upon coating a single side with AlF

3, the average transmittance increases markedly to (94.5 ± 0.4)%, directly reflecting the suppression of front-surface reflection through effective refractive-index matching. When both sides are coated, the average transmittance is further boosted to an impressive (97.6 ± 0.5)%, demonstrating that the AlF

3 layer efficiently suppresses reflection losses across the entire visible spectrum. To verify the accuracy of the extracted optical constants and assess the theoretical limit of the coating, optical simulations based on the transfer-matrix method (TMM) were performed. The model utilized the refractive index dispersion and thickness values determined from ellipsometry, treating the AlF

3 layer as a coherent thin film and the thick glass substrate as an incoherent medium. As shown in

Figure 9a, the simulated spectra (dashed lines) overlay the measured data (solid lines) with remarkable precision. The excellent agreement between the model and the experiment confirms the validity of the optical parameters and demonstrates that the PEALD AlF

3 films achieve an antireflective performance virtually identical to the theoretical design target.

Figure 9b shows the corresponding transmission color coordinates (CIE 1931 (x, y)) for the bare and coated samples, calculated from the measured transmittance spectra using the D65 illuminant and the 2° standard observer. While the bare glass lies close to the D65 white point, both the single- and double-sided AlF

3-coated glasses shift toward the theoretical achromatic point (x = 0.333, y = 0.333). This behavior indicates that the PEALD AlF

3 coating not only enhances the overall transmittance but also improves the color neutrality of transmitted light, effectively reducing residual tint from the substrate. Taken together, these optical results establish the PEALD AlF

3 film as a highly effective, color-neutral antireflective coating. The combination of ultralow refractive index, extremely smooth morphology, and excellent stoichiometric control enables simultaneous optimization of transmission efficiency and spectral neutrality—key requirements for high-end optical components, display cover glasses, and precision sensing systems.

In

Figure 10, photographs of a bare glass substrate and a double-sided AlF

3-coated sample are shown under identical fluorescent illumination positioned directly above the specimens and viewed at an oblique angle. The bare glass exhibits strong surface reflectivity, evidenced by pronounced, bright glare from the light source that partially obscures the underlying text. By contrast, the AlF

3-coated glass shows a marked suppression of this specular reflection, rendering the printed letters beneath the substrate noticeably clearer and more legible. The reduced glare and enhanced contrast provide an intuitive, side-by-side visualization of the antireflective effect, in excellent agreement with the quantitative transmittance and colorimetric data. This simple optical demonstration highlights the practical efficacy of the PEALD AlF

3 coating in improving visual clarity and overall light transmission in real-world viewing conditions.

Table 3 compares the AlF

3 film properties and antireflective performance achieved in this work with those reported previously. Conventional physical vapor routes, such as evaporation and sputtering, typically produce AlF

3 coatings with relatively high RMS roughness (≈1.45 nm and ≈0.8 nm, respectively [

23,

29]), which enhances light scattering and inherently limits antireflective performance. Among ALD methods, TALD processes using metal–fluoride precursors (e.g., TiF

4 or TaF

5) can avoid the use of HF but often suffer from significant impurity incorporation (2–8.3 at.%) or lower growth rates [

14,

34,

35]. Similarly, ALD routes relying on anhydrous HF, including both thermal and plasma-enhanced modes, not only raise serious safety and equipment corrosion concerns but also typically yield residual impurity levels between 2 and 14 at.% [

12,

17,

36]. Even regarding the safer SF

6-based PEALD approach, previous studies generally reported impurity contents in the range of 2.0–2.7 at.% [

15,

37,

38]. In distinct contrast, the PEALD strategy developed here advances the state-of-the-art by simultaneously optimizing safety, purity, and morphology. By combining high-vacuum pre-deposition with a PTFE-lined plasma tube and optimized pulse kinetics, we achieve an ultra-low total impurity content of only 0.86 at.%. This represents a significant improvement not only over hazardous HF-based methods but also over prior SF

6-based reports. Furthermore, our process delivers an atomically smooth surface (RMS ~0.24 ± 0.03 nm) and a low refractive index (1.35), both hallmarks of dense, high-quality AlF

3 films. Taken together, these results demonstrate that our HF-free PEALD process offers a safer, more robust route that surpasses existing methods in both structural quality and functional optical performance.