3.1. Optimization of Electromagnetic Parameters and Structural Geometry

This section investigates the electromagnetic absorption loss mechanisms in the fiber-reinforced periodic gradient absorbers, which stem from the synergistic contributions of magnetic and dielectric losses and are closely tied to impedance matching behavior. The outer dielectric structure exhibits multiple internal reflections, allowing the SP1 configuration to optimize impedance matching. Although SP1 offers superior wave transmittance, its intrinsic loss capability is weaker than that of SP2. Here, SP1 and SP2 refer to composite systems comprising MWCNTs and polyurethane in mass ratios of 0.5:99.5 and 1:99, respectively. Similarly, DS1 and DS2 refer to carbonyl iron powder (SCIP) and PU mixed at ratios of 83.3:16.6 and 66.6:33.3, respectively.

For the magnetic skin layer, DS1 demonstrates stronger energy dissipation than DS2, largely due to its thinner configuration, which promotes enhanced magneto-electric coupling. Therefore, considering both impedance matching and loss efficiency, the combination of SP1 in the dielectric gradient structure and DS1 in the magnetic skin structure is the most favorable configuration for achieving optimal microwave absorption performance.

In the preliminary design phase, a range of electromagnetic parameter combinations was developed by systematically adjusting component concentration gradients. This yielded six representative parameter groups: SP1 + SP2, DS1 + DS2, SP1 + DS1, SP1 + DS2, SP2 + DS1, and SP2 + DS2, designated as G1 through G6. As illustrated in

Figure 2a, the dielectric-only group exhibited weak energy loss and a singular loss mechanism, resulting in limited absorption performance. In contrast, the magnetic-only group performed well in the low-frequency region but lacked effectiveness at higher frequencies. Among the remaining four hybrid combinations, G3—consisting of SP1 and DS1—achieved the best overall microwave absorption performance.

The skin layers were fabricated by stacking and curing the prepared prepregs. Within the skin structure, the embedded fiber cloth serves as the impedance matching layer, while the applied wave-absorbing adhesive acts as the functional coating responsible for electromagnetic absorption. The fiber cloth not only reinforces the structural integrity but also supports layered architecture, thereby enhancing the mechanical strength and facilitating multiple internal wave reflections and absorption.

By configuring the outer dielectric layer as a dedicated matching layer and isolating the magnetic loss behavior of the inner layer, the power dissipation of each component, as well as the transmission characteristics of the outer dielectric structure, can be independently evaluated. Among the reference groups, G1 (optimized for dielectric gradient) and G2 (optimized for magnetic gradient) were selected for comparative analysis. G1 displayed poor absorption due to its low dielectric content, resulting in an ineffective loss mechanism. G2, on the other hand, failed to establish sufficient magneto-electric coupling at high frequencies, leading to significant impedance mismatch.

Through further optimization of the concentration gradients in groups G3 through G6, it was determined that SP1 is the preferred outer layer for enhancing magneto-electric synergy with the underlying carbonyl iron layer, in contrast to SP2. The relatively low concentration of MWCNTs in SP1 leads to a less developed conductive network, which improves transmission while reducing reflectivity—an effect beneficial for matching. In comparison, the bottom layer configured with DS2, which contains a higher fraction of carbonyl iron, substantially improves microwave magnetic loss capability. Notably, although increased carbonyl iron content may contribute to higher reflectivity, its adverse effects are mitigated by the enhanced intrinsic magnetic loss, thus supporting the overall absorption efficiency of the structure.

Among the six configurations, G3 was selected as the optimal combination for impedance matching, yielding superior broadband absorption performance. To further enhance this effect, the dielectric coating layer was designed as a gradient meta-structure with its performance tuned by varying the prism inclination angle. The meta-structure height was fixed at 2 mm, while the inclination angle between the prism’s side and the vertical axis was adjusted systematically. As shown in

Figure 2b, increasing the angle led to a progressive reduction in the overall volume of the meta-structure; nevertheless, the effective absorption bandwidth was significantly broadened, despite a slight decrease in peak absorption. At an optimal angle of 70 degrees, the structure’s volume was reduced to just one-quarter of an equivalent full-thickness layer, yet absorption performance was substantially improved. The “tower-like” morphology of this configuration proved particularly effective for capturing obliquely incident waves. The inclined gradient sides promoted multiple internal reflections, enhancing the electromagnetic wave attenuation through angular scattering paths. This multi-scattering mechanism compensates for reduced material thickness by increasing effective propagation length and dissipative interactions.

To investigate the effect of the fiber-reinforced structure, a series of samples with varying numbers of fiber cloth layers were fabricated. As illustrated in

Figure 2c, increasing the number of fiber layers led to a progressive enhancement of the wave absorption modulation effect. Both the absorption peak frequency and magnitude were observed to rise with added layers. Notably, the incorporation of two layers of fiber cloth provided a balanced structure: it ensured that the high-frequency absorption peak remained within the effective attenuation range while minimizing undesired low-frequency shifts.

In order to further examine the interplay between meta-structure and magnetic skin thickness on absorption performance, six sample groups (S1–S6) were designed with fixed total thicknesses of 3, 4, and 5 mm. For the 3 mm group, S1 employed a meta-structure and skin thickness of 1 mm and 2 mm, respectively, while S2 used the reverse configuration. For the 4 mm group, S3 featured 2 mm meta-structure and 1 mm skin, while S4 had 1 mm and 2 mm, respectively. Similarly, S5 and S6 in the 5 mm group featured meta-structure/skin combinations of 3 mm/2 mm and 2 mm/3 mm, respectively.

The absorption spectra of S1–S6, as shown in

Figure 2d, revealed that samples with thinner meta-structures and thicker skin layers exhibited red-shifted absorption peaks and poor impedance matching at high frequencies. Conversely, increasing the meta-structure thickness relative to the skin led to a blue shift in the absorption peak and improved high-frequency matching. S2 and S4 demonstrated this effect clearly, confirming that a thicker meta-structure with a thinner magnetic skin benefits high-frequency impedance alignment. In contrast, S1 and S3, despite having good low-frequency coverage, suffered in the high-frequency range due to impedance mismatch. Sample S6, with its excessively thick meta-structure, exhibited degraded wave transmission and further mismatch. S5 showed the poorest performance overall, as the combined effects of high impedance mismatch and low transmission efficiency limited both absorption bandwidth and peak strength. These findings underscore the need to consider not only intrinsic material losses but also wave transmission and impedance matching in absorber structural design.

Based on a comprehensive analysis, sample S2—with a total thickness of 3 mm—was selected as the representative configuration for this study, balancing compact structure with optimal impedance matching. As shown in

Figure 2e, simulations of structures N0 through N7 revealed that increasing the FR4 layer thickness caused a noticeable shift in absorption peaks toward higher frequencies. Notably, a secondary peak begins to emerge around 18 GHz, suggesting that fine-tuning of FR4 thickness could further expand the absorption bandwidth into the 18–30 GHz range.

Thus, the dielectric constant was derived using the first-order Debye equation. From this derivation, it is evident that the first-order Debye model effectively characterizes the frequency response behavior of dielectric materials, particularly describing the dielectric relaxation phenomena of polar molecules. The corresponding expression for the complex dielectric constant provides a theoretical basis for understanding the variation in permittivity across different frequencies.

Based on this model, the microwave absorption performance of FR4 layers with varying thicknesses in the 2–30 GHz range was simulated using HFSS, as illustrated in

Figure 2f (N0–N7). The results show a progressive shift in the absorption peaks toward lower frequencies as the FR4 thickness increases from 0.1 mm to 0.7 mm. This redshift is attributed to enhanced impedance matching and improved transmission characteristics of FR4, which also contributes to superior absorption performance in the high-frequency region.

Integrating the above findings, the FR4 wave-transmissive layer plays a dual role in wavelength matching and phase modulation. Specifically, the inclusion of a 0.5 mm FR4 layer optimizes the transmission of incident electromagnetic waves and facilitates absorption peak shifts to lower frequencies. For instance, the N5 configuration exhibits dual-peak absorption at 11.2 GHz and 22.8 GHz, effectively broadening the total absorption bandwidth to 17.8 GHz.

Based on the above study, a dual-gradient electromagnetic parameter design was developed to optimize both impedance matching and energy attenuation capability. The gradual modulation of the dielectric constant and magnetic permeability is achieved through the combined effect of the periodic gradient dielectric structure (SP1–SP2) and the magnetic surface layer (DS1–DS2).

In this configuration, the low concentration of MWCNTs (0.5%) in the outer layer improves electromagnetic wave transmittance, while the high concentration of CIP (83.3%) in the inner layer enhances magnetic loss, thereby resolving the impedance mismatch problem commonly associated with single-mechanism loss systems.

Furthermore, the dual-gradient structure enables significant volume reduction while maintaining effective broadband absorption. Specifically, a tower-type superstructure unit with a prism side inclination angle of 70° is adopted, resulting in a unit volume that is only one-quarter that of a conventional homogeneous structure. Simultaneously, the inclined geometry extends the propagation path of electromagnetic waves through multiple internal reflections—up to 1.7 times the wavelength—leading to more than 85% energy attenuation and ensuring effective absorption across the X, Ku, and K bands (8.6–26.4 GHz). The design also introduces a fiber-reinforced structure as a novel element.

Mechanical–electromagnetic synergistic design: Glass fiber cloth is utilized as a structural support layer, and the micron-scale surface height variation promotes the orderly dispersion of the absorber. This not only enhances the mechanical strength of the structure—making it suitable for aerospace load-bearing applications—but also helps mitigate interfacial impedance mismatch.

Additionally, the use of multilayer fiber cloth plays a regulatory role in tuning the absorption frequency bandwidth. Specifically, in the ASM structure, the introduction of a double-layer fiber cloth enhances the stability of high-frequency absorption peaks while preventing shifts in the low-frequency peak position, thereby achieving an optimal balance between broadband absorption performance and mechanical robustness.

3.2. Performance Validation

(

Figure 3c–f) display the measured and simulated performance of SP + DS1 absorbing structures without FR4, SP2 + DS1 absorbing structures without FR4, SP1 + DS1 absorbing structures with FR4, and SP2 + DS1 absorbing structures with FR4, respectively. The reflection loss of the samples was measured in a microwave anechoic chamber, and the tests were conducted over the 2–18 GHz frequency range using the arched method, as depicted in

Figure 3c. The effective absorption bandwidth of these structures is closely related to their peak absorption values. According to established literature on wave absorption, the measured absorption performance of the structures is generally weaker than that of the simulated structures due to errors arising from CIP settling and the mold preparation process. However, it is noteworthy that the measured performance of the structures in (

Figure 3c,d) exceeds that of the simulated structures, while the measured performance of the structures in

Figure 3e,f is inferior to the simulated counterparts. This discrepancy can be attributed to the bottom layer of the masks, which consists of multilayer fiber cloth brushed and coated with curing adhesive.

The bottom layer consists of a multilayer fiber fabric that has been brushed, coated with wave-absorbing adhesive, and subsequently cured. In the simulated structure, the fiber cloth within the skin layer functions as an impedance matching layer, while the wave-absorbing adhesive serves as a coating that operates as the primary absorption layer.

The fiber cloth plays a dual role as both a structural support material and a layered template, significantly enhancing the composite’s mechanical strength and electromagnetic absorption performance. Notably, the surface of the glass fiber cloth presents a distinctive micron-scale height variation and inter-fiber gaps, which promote the orderly distribution of absorber particles across the fiber layer.

This two-dimensional fiber cloth templating strategy effectively mitigates the negative effects of CIP sedimentation and fabrication inconsistencies associated with mold preparation, thereby contributing to improved reliability and uniformity in wave-absorbing performance.

The performance degradation observed in

Figure 3e,f is attributed to the inherent difficulties in fabricating meta-structures with high concentrations of MWCNTs, as compared to those using lower concentrations within the matrix. During the mold preparation process, partial gelation of MWCNTs may occur, leading to the formation of a localized conductive network that hinders the transmission of electromagnetic waves.

This electromagnetic shielding effect counteracts, to some extent, the beneficial influence of the two-dimensional fiber cloth template, ultimately causing the measured absorption performance to fall below the levels predicted by simulation.

Figure 3b presents the simulated absorption performance of the N0–N7 structural configurations across the 2–30 GHz frequency range. In this context, RLmin (dB)1 and RLmin (dB)2 represent the first and second effective absorption peaks, respectively, while Peak Frequency 1 and Peak Frequency 2 denote the corresponding resonance frequencies. The effective absorption bandwidth (EAB) refers to the total frequency range over which the absorption exceeds the effective threshold.

These N0–N7 structures are designed as superstructures incorporating FR4 layers of varying thicknesses ranging from 0 to 0.7 mm. Among them, the N5 configuration demonstrates an EAB of 17.8 GHz, with the first and second absorption peak values reaching −19 dB and −22 dB at 11.2 GHz and 22.8 GHz, respectively.

Although N5’s total EAB is slightly narrower than that of N3 (19.8 GHz), it exhibits a well-defined dual-peak absorption profile, with strong performance extending into the lower portion of the K-band. The ASM structure—featuring a 0.5 mm FR4 layer as its outer superstructural component—not only benefits from intrinsic and structural loss mechanisms but also warrants deeper investigation into the underlying physical principles contributing to its exceptional absorption performance.

3.3. Electric/Magnetic Field Distribution and Loss Mechanisms

As shown in

Figure 4a,b, with increasing frequency, the region of electromagnetic wave loss progressively shifts toward the interior of the material. Analysis of the electromagnetic field distribution in materials with uniform thickness reveals distinct variations in absorption behavior. The introduction of a heterogeneous interface leads to improved impedance matching performance.

The incorporation of a meta-structured layer introduces multiple internal reflections and distinctive transmission characteristics. These arise from the incomplete conductive network formed by carbon nanotubes within the resin matrix, in conjunction with the intrinsic geometric features of the meta-structure. Together, these effects result in enhanced absorption performance.

As frequency increases, the electric field begins to extend from the interior toward the exterior regions of the absorber. Notably, the strongest absorption is observed at 10.4 GHz, which is attributed to the synergistic effect of pronounced magnetic loss in the bottom layer and the heterogeneously distributed electromagnetic parameters in the outer dielectric layer.

The current wave-absorbing structure, comprising a combination of wave-transparent, dielectric, and magnetic components, exhibits more complex electromagnetic field evolution compared to conventional homogeneous absorbers. Relative to the ASM structure without the FR4 layer, the SAM demonstrates a gradual enhancement in electric field intensity as frequency increases, reaching its maximum at 13.2 GHz.

However, beyond this frequency, the electric field strength decreases progressively from the top surface toward the bottom layer, indicating a reduction in wave-absorbing performance. This degradation is primarily attributed to magneto-electric mismatch arising at higher frequencies.

Consequently, in the gradient structure, electromagnetic wave loss gradually shifts from the bottom layer toward the top as frequency increases. In the absence of an FR4 layer, the meta-structure exhibits poor impedance matching with incident electromagnetic fields at high frequencies, thereby inhibiting the effective penetration of waves into the structure.

As a result, both magnetic and overall power losses are less significant under conditions without FR4 compared to those with FR4. The relatively weak absorption observed at low frequencies is primarily attributed to the presence of dielectric components, which hinder the transmission of electromagnetic waves in the lower frequency range.

Within the frequency interval of 8.6 to 11.2 GHz, the electric field gradually attenuates. The initial peak in the external electromagnetic field is primarily driven by the combined effects of dielectric and magnetic losses. This coupling enhances impedance matching and facilitates deeper wave penetration into the material.

In contrast, the incorporation of the FR4 layer in the ASM structure results in an extended effective wavelength and causes a redshift in the absorption peak toward lower frequencies. As shown in

Figure 4c, compared to the case without FR4, the electric field distribution at the first absorption peak demonstrates a pattern of initial attenuation followed by local enhancement. Specifically, the electric field initially diffuses and attenuates from the outer region toward the inner layer, followed by repeated localized enhancements—reflecting the progressive energy dissipation during inward field propagation.

Additionally, the introduction of layered metamaterial interfaces induces pronounced interfacial effects, which significantly contribute to electromagnetic energy dissipation and enhance the overall absorption capacity of the structure. Based on the above analysis, the ASM achieves a strong magneto-electric coupling effect: the bottom CIP/PU layer serves as the magnetic loss region, while the surface MWCNTs/PU layer functions as the dielectric loss region. These layers act synergistically, with magnetic losses dominating in the high-frequency range (>10 GHz), and dielectric losses prevailing in the low-frequency range (<10 GHz), thereby enabling highly efficient absorption across the full operating bandwidth.

This performance enhancement is primarily attributed to interfacial energy dissipation induced by the gradient structure. The heterogeneous interface initiates strong interfacial polarization effects, leading to stepwise attenuation of incident electromagnetic waves from the exterior to the interior of the absorber, as illustrated in

Figure 4a–c. The observed absorption peak at 10.4 GHz results from the synergistic matching between magnetic loss and the spatial variation in electromagnetic parameters.

3.4. Phase Modulation and Interference Effects

The phase difference between reflected waves at the front and rear interfaces of the absorber plays a crucial role in determining electromagnetic wave reflection behavior. When the material thickness is equal to one-quarter of the incident wavelength, the reflected wave acquires a phase shift of 180 degrees (or π radians) relative to the incident wave upon reciprocal propagation.

This phase shift induces destructive interference between the forward and backward reflected waves, effectively canceling out the reflected signal and significantly reducing total reflection. In practice, the two key interfaces—the air–absorber boundary and the absorber–metal substrate interface—each contribute reflected waves, and the phase relationship between them directly governs the absorber’s overall effectiveness.

When the phase difference between the two reflected waves equals an odd multiple of half the wavelength, destructive interference occurs, significantly enhancing electromagnetic wave attenuation. In contrast, if the phase difference corresponds to an even multiple of half the wavelength, constructive interference takes place, thereby reducing the overall attenuation efficiency.

Understanding the influence of material properties and microstructural features on electromagnetic wave absorption is fundamental to analyzing attenuation behavior. Effective absorber design requires not only consideration of the material’s intrinsic absorption characteristics but also the integration of wave interference theory—particularly the quarter-wavelength principle—to optimize performance.

This involves tuning the phase relationship between the reflected waves at the air–absorber interface (denoted as Rf) and those at the absorber–metal backing interface (denoted as Rb), thereby enhancing destructive interference and minimizing overall reflection.

As shown in

Figure 5a,b, we analyzed the quantitative interference effects and intrinsic attenuation behavior of a 2.5 mm FR4-free SAM structure and a 3 mm ASM structure using wave interference theory and a symmetry-based modeling approach. As illustrated in

Figure 5(c

1), the reflection loss (RL) peak of the SAM coincides with a 180° phase shift, indicating a strong destructive interference condition. In contrast,

Figure 5(d

1) shows that the phase inflection point in the ASM—with the introduction of the FR4 layer—also corresponds to its absorption peak. However, the presence of a dual-phase deflection results in partial degradation of absorption performance.

Figure 5(c

2,d

2) indicates that within the frequency range where reflectivity is low, the front interface reflection wave Rf and the rear interface reflection wave Rb exhibit similar amplitudes. Furthermore, a phase difference of approximately 180° exists between them, equivalent to roughly half a wavelength. From the analysis in

Figure 5(c

3,d

3), it is evident that the unique gradient structure of the SAM significantly enhances its intrinsic broadband absorption capability, while also suppressing the adverse effects of phase-length interference. Furthermore, the ASM, enhanced by the FR4 layer, increases the number of heterogeneous interfaces, thereby reinforcing the phase cancellation effect. This results in a marked improvement in broadband absorption efficiency.

These findings confirm that the ASM structure achieves a reduced RL slope in the high-frequency regime and realizes ultra-broadband absorption. This performance is not only attributed to the gradient structural design of the SAM and the impedance-matching benefits provided by the FR4 layer, but also validates the effectiveness of the theoretical framework and design methodology proposed in this study.

3.5. Radar Cross-Section and Polarization Characteristics

The radar far-field scattering cross-section (RCS), which reflects polarization sensitivity, is a key metric for evaluating the performance of materials in electromagnetic environments. To investigate the stealth capability of the ASM structure, we conducted simulations using the HFSS platform. As shown in

Figure 6a–c, an RCS model of the ASM was constructed, and far-field scattering analyses were performed at the absorption peaks under normal incidence. The results were compared against a reference perfect electric conductor (PEC).

The simulation reveals that the maximum scattering peaks at 11.2 GHz, 15.6 GHz, and 22.4 GHz are notably reduced for the ASM compared to the PEC, indicating a significant suppression of radar detectability and confirming the structure’s effective stealth performance.

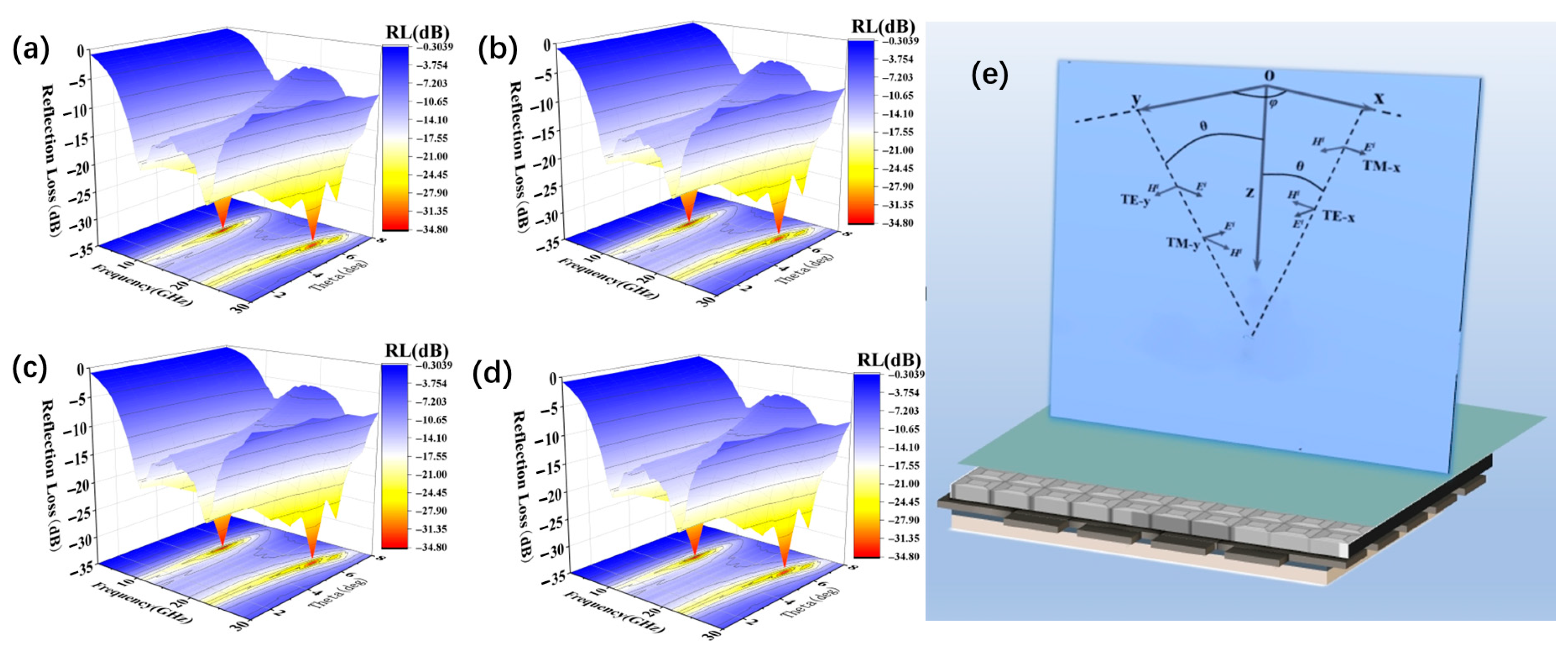

In addition, simulations were performed to assess the polarization sensitivity and angular stability of both ASM and SAM. As illustrated in

Figure 7a–e, the absorption rates under transverse electric (TE) and transverse magnetic (TM) polarization modes were analyzed at varying polarization angles. The results demonstrate that the ASM maintains stable absorption performance as the polarization angle increases.

This polarization insensitivity is attributed to the structure’s fourfold rotational symmetry, which ensures consistent performance regardless of polarization direction. The dual-peak absorption response remains robust, particularly under TE polarization, where stable absorption is sustained at incident angles up to 60°.

Furthermore, the RCS reduction reaches 15 dB at 22.4 GHz (

Figure 6), while polarization stability is preserved up to 60° (

Figure 7). As shown in

Table S1, the “fiber-reinforced periodic impedance gradient” strategy proposed in this study overcomes the inherent trade-offs between broadband performance, thin-layer thickness, wide-angle stability, and mechanical strength in conventional absorbers. This is achieved through the synergistic interaction of dual gradient parameters with structural design. While the fabrication process is relatively complex, it provides a critical solution for high-performance application scenarios.