Preparation of Fe/PANI/GF Composite and Study on Its Interfacial Evaporation Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Instruments

2.1.1. Main Materials

2.1.2. Main Instruments

2.2. Preparation of Fe/PANI/GF

2.2.1. Pretreatment of GF

2.2.2. Preparation of PANI/GF Composite

2.2.3. Preparation of Fe/PANI/GF Composite

2.3. Material Characterization

2.4. Evaporation Performance Test

3. Results

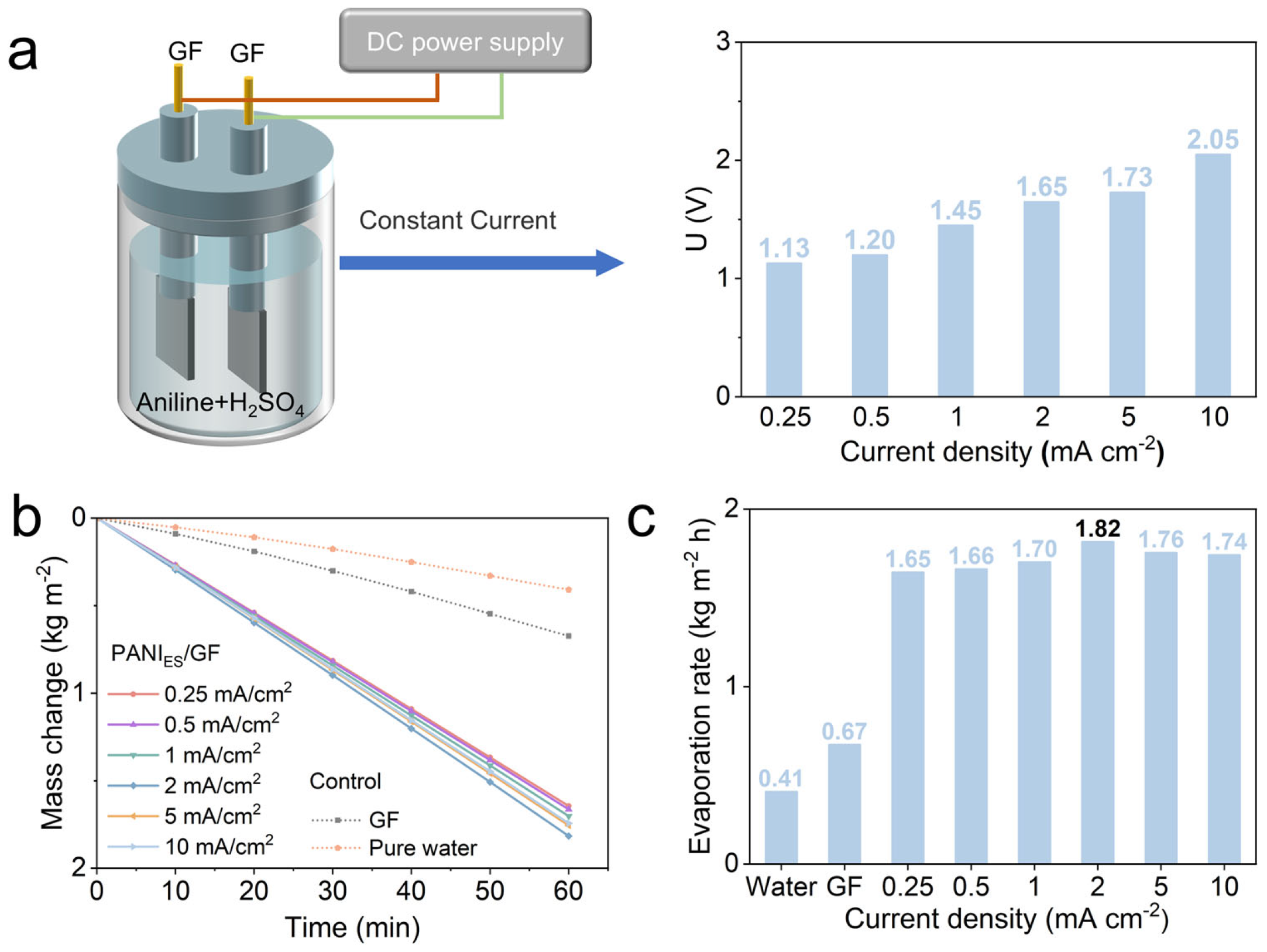

3.1. The Optimization of Electrodeposition Current Density for PANI/GF and Its Effect on Evaporation Performance

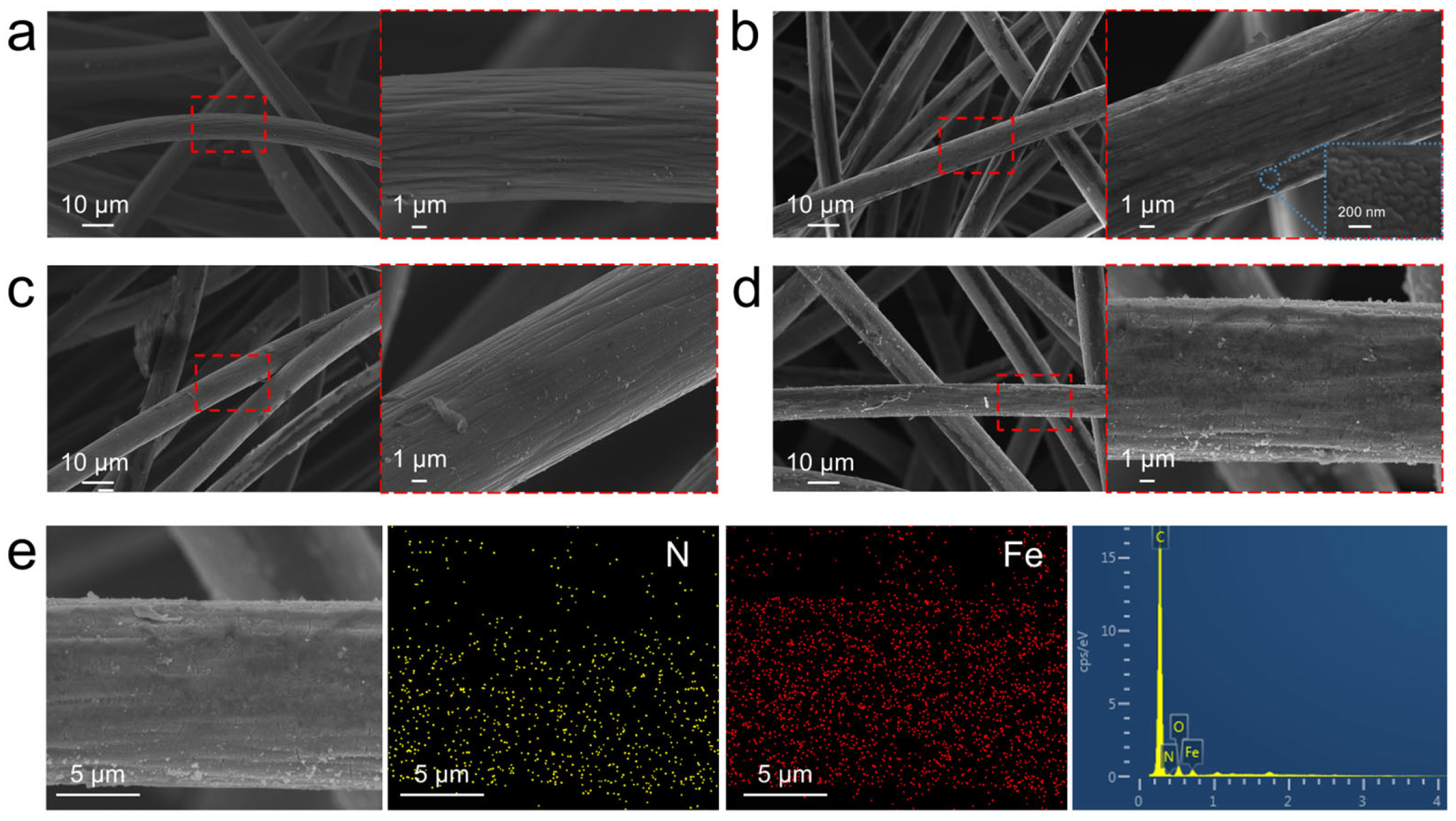

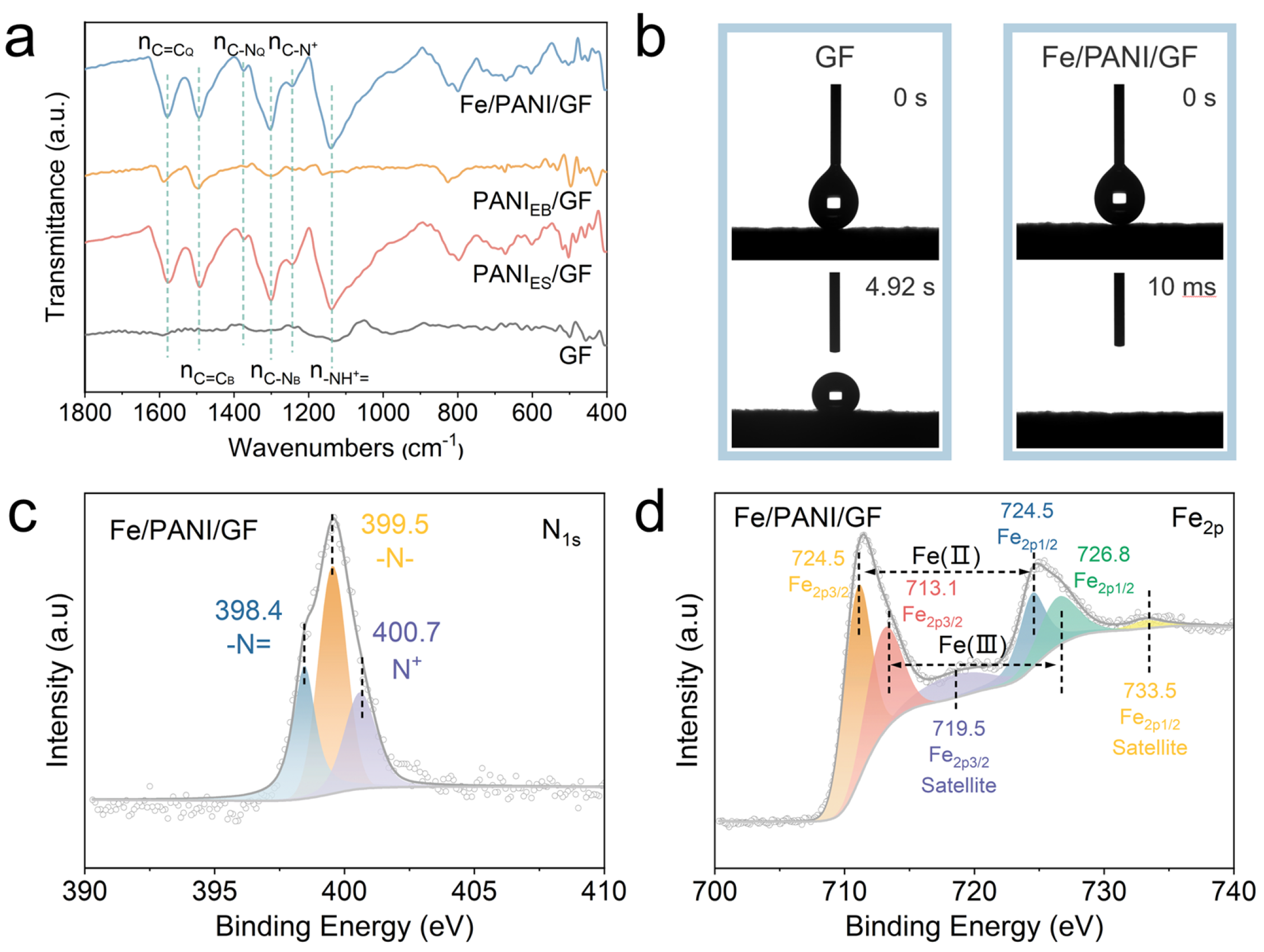

3.2. Morphology and Characterization of GF, PANI/GF, and Fe/PANI/GF Composites

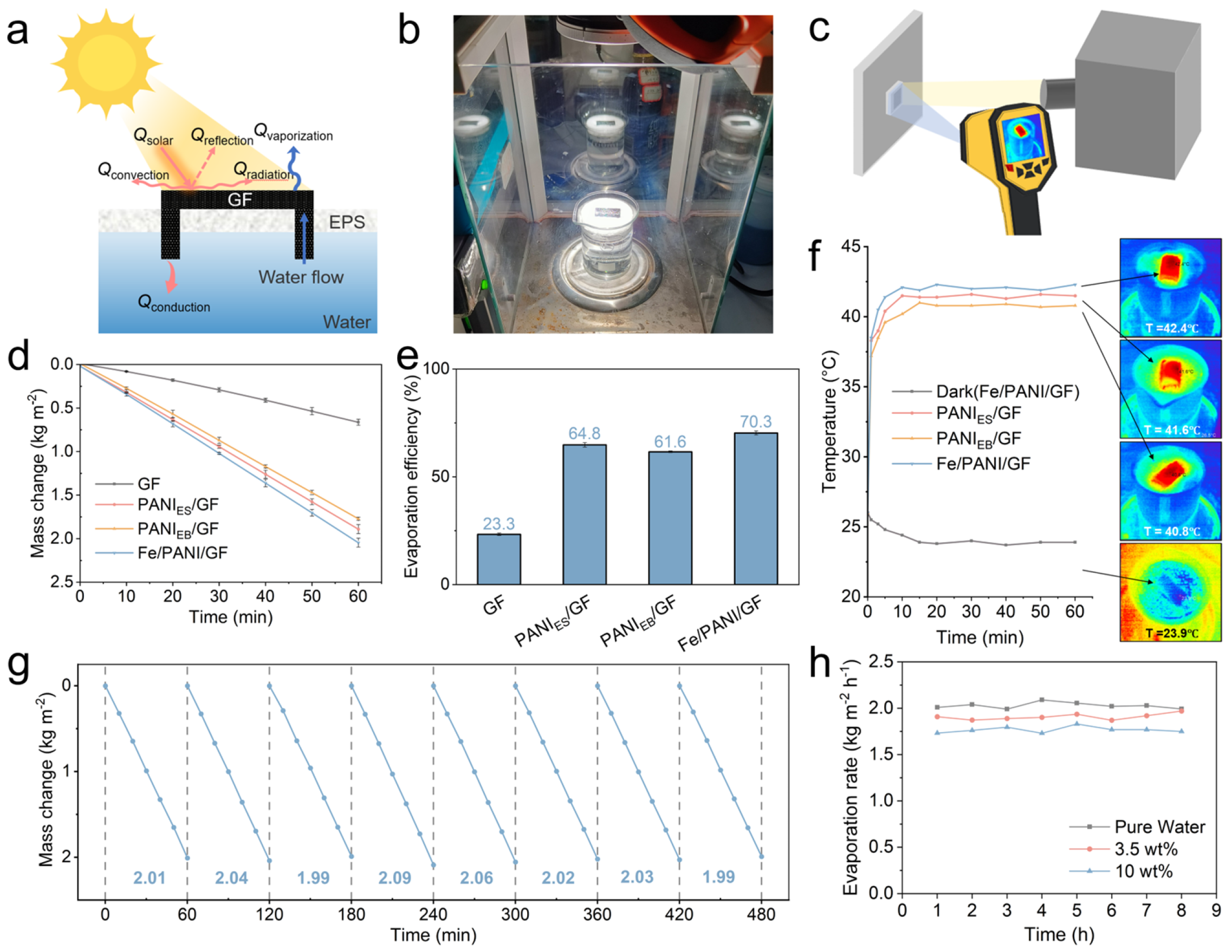

3.3. Photothermal Conversion Performance of GF, PANI/GF, and Fe/PANI/GF Composites

3.4. Photothermal Evaporation Performance of GF, PANI/GF, and Fe/PANI/GF Composites

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SDIE | Solar-driven Interfacial Evaporation |

| PANI | Polyaniline |

| GF | Graphite felt |

References

- Elimelech, M.; Phillip, W.A. The Future of Seawater Desalination: Energy, Technology, and the Environment. Science 2011, 333, 712–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, A.; Lu, J.-Y.; Alzaim, S.; Li, H.; Zhang, T. Novel Receiver-Enhanced Solar Vapor Generation: Review and Perspectives. Energies 2018, 11, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Guo, Y.; Zhou, X.; Shi, W.; Yu, G. Materials for Solar-Powered Water Evaporation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2020, 5, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, N.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, J.; Gao, B.; Li, Q. A Self-floating Photothermal/Photocatalytic Evaporator for Simultaneous High-efficiency Evaporation and Purification of Volatile Organic Wastewater. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2500777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lu, Y.; Ren, X.; Wu, P.; Chu, D.; Yang, X.; Xu, H. Interfacial Solar Evaporation: From Fundamental Research to Applications. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2313090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, X.; Mu, C.; Liu, Y.; Wu, L.; Tong, Z.; Huang, K. Recent Advances in Solar-Driven Interfacial Evaporation Coupling Systems: Energy Conversion, Water Purification, and Seawater Resource Extraction. Nano Energy 2024, 120, 109180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Lin, S.; Alshrah, M.; Zhao, X.; Chen, G. Plausible Photomolecular Effect Leading to Water Evaporation Exceeding the Thermal Limit. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2312751120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Hou, X.; Wang, H.; Shi, H.; Miao, Y.; Bian, Z. Preparation of Porous Biomimetic Biochar-Based Photothermal Conversion Materials and Development of Air Water Harvesting Devices. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2025, 17, 37216–37230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Ni, G.; Cooper, T.; Xu, N.; Li, J.; Zhou, L.; Hu, X.; Zhu, B.; Yao, P.; Zhu, J. Measuring Conversion Efficiency of Solar Vapor Generation. Joule 2019, 3, 1798–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-L.; Han, S.-J.; Xu, L.; Wang, Z.-Y.; Labiadh, L.; Fu, M.-L.; Yuan, B. Recent Progress of Solar-Driven Interfacial Evaporation Based on Organic Semiconductor Materials. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 326, 124759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Pan, G.; Yan, M.; Wang, F.; Wu, Y.; Guo, C. Janus Membrane with Enhanced Interfacial Activation for Solar Evaporation. J. Energy Chem. 2023, 87, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Zhou, C.; Yang, L.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Tian, J.; Wu, W. Multifunctional Cotton with PANI-Ag NPs Heterojunction for Solar-Driven Water Evaporation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macdiarmid, A.G.; Chiang, J.C.; Richter, A.F.; Epstein, A.J. Polyaniline: A New Concept in Conducting Polymers. Synth. Met. 1987, 18, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Xiong, J.; Zeng, H.; Liao, M. Polyaniline-ZnTi-LDH Heterostructure with d–π Coupling for Enhanced Photocatalysis of Pollutant Removal. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 684, 792–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Yue, D.; Liu, F.; Yu, J.; Li, B.; Sun, D.; Ma, X. Acid-Doped Polyaniline Membranes for Solar-Driven Interfacial Evaporation. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 40, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, T.; Lei, Y.; Shu, T.; Qin, Y.; Guo, N.; Chen, X. Photothermal Coupling of Low-Grade Waste Heat to Achieve High Efficiency Fresh Water Production via Sponge-Based Evaporator. Desalination 2025, 612, 118988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beygisangchin, M.; Hossein Baghdadi, A.; Kartom Kamarudin, S.; Abdul Rashid, S.; Jakmunee, J.; Shaari, N. Recent Progress in Polyaniline and Its Composites; Synthesis, Properties, and Applications. Eur. Polym. J. 2024, 210, 112948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y.-J.; Wen, W.; Wu, J.-M. Simple Air Calcination Affords Commercial Carbon Cloth with High Areal Specific Capacitance for Symmetrical Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 21078–21086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, H.; Wang, Y. Electro-Polymerization Fabrication of PANI@GF Electrode and Its Energy-Effective Electrocatalytic Performance in Electro-Fenton Process. Chin. J. Catal. 2016, 37, 2079–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Li, H.; Fu, X.; Zhao, C.; Li, M.; Liu, M.; Yan, W.; Yang, H. Fe Single-Atom Catalyst for Cost-Effective yet Highly Efficient Heterogeneous Fenton Catalysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 53767–53776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Shen, X.; Kim, E.; Wang, M.; Lee, J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, G.; Kim, J. Integrated Water and Thermal Managements in Bioinspired Hierarchical MXene Aerogels for Highly Efficient Solar-powered Water Evaporation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2111794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Peng, Y.; Fang, W.; Hu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhang, S.; Jin, J. A Polyaniline Nanofiber Array Supported Ultrathin Polyamide Membrane for Solar-Driven Volatile Organic Compound Removal. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 20424–20430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Meng, X.; Zou, H.; Wang, Z.; Du, Y.; Shao, Y.; Qi, J.; Qiu, J. Topographic Manipulation of Graphene Oxide by Polyaniline Nanocone Arrays Enables High-performance Solar-driven Water Evaporation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2209207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapakse, R.M.G.; Krishantha, D.M.M.; Tennakoon, D.T.B.; Dias, H.V.R. Mixed-Conducting Polyaniline-Fuller’s Earth Nanocomposites Prepared by Stepwise Intercalation. Electrochim. Acta 2006, 51, 2483–2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, A.G.; Gök, A. Preparation of TiO2/PANI Composites in the Presence of Surfactants and Investigation of Electrical Properties. Synth. Met. 2007, 157, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Jing, X.; Wang, B.; Wang, F. Infrared Spectra of Soluble Polyaniline. Synth. Met. 1988, 24, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.T.; Neoh, K.G.; Tan, T.C.; Khor, S.H.; Tan, K.L. Structural Studies of Poly(p-Phenyleneamine) and Its Oxidation. Macromolecules 1990, 23, 2918–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, D.; Hou, G.; Li, J.; Wen, T.; Ren, X.; Wang, X. PANI/GO as a Super Adsorbent for the Selective Adsorption of Uranium(VI). Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 255, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosvenor, A.P.; Kobe, B.A.; Biesinger, M.C.; McIntyre, N.S. Investigation of Multiplet Splitting of Fe 2p XPS Spectra and Bonding in Iron Compounds. Surf. Interface Anal. 2004, 36, 1564–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Yu, H.; Tang, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, S.H.; Zhao, H.; Mandler, D. 3D Spongy Nanofiber Structure Fe–NC Catalysts Built by a Graphene Regulated Electrospinning Method. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 6277–6280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Gao, T.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, D. Self-Assembled Fe, N-Doped Chrysanthemum-like Carbon Microspheres for Efficient Oxygen Reduction Reaction and Zn–Air Battery. Energy Technol. 2020, 8, 2000145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Chen, S.; Yang, X.; Ma, N.; Xia, Y.; Yang, D.; Guo, S. Suppressing Fe–Li Antisite Defects in LiFePO4/Carbon Hybrid Microtube to Enhance the Lithium Ion Storage. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1601549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, W.; Wang, K.; Yin, W.; Chai, W.; Tang, B.; Rui, Y. Rodlike FeSe2–C Derived from Metal Organic Gel Wrapped with Reduced Graphene as an Anode Material with Excellent Performance for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrochim. Acta 2019, 323, 134817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, P.; Fu, X.; Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Tang, R.; Du, X.; Chen, W.; Li, S.; et al. Flatband λ-Ti3O5 towards Extraordinary Solar Steam Generation. Nature 2023, 622, 499–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Lu, J.; Xu, N.; Chen, C.; Min, X.; Zhu, B.; Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, S.; et al. Enhancement of Interfacial Solar Vapor Generation by Environmental Energy. Joule 2018, 2, 1331–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, J.; Wei, X.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Yan, B.; Pan, X.; Zhang, Z.; Wu, Y.; Shi, B.; Yang, H. Preparation of Fe/PANI/GF Composite and Study on Its Interfacial Evaporation Performance. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010024

Guo J, Wei X, Wang M, Li X, Yan B, Pan X, Zhang Z, Wu Y, Shi B, Yang H. Preparation of Fe/PANI/GF Composite and Study on Its Interfacial Evaporation Performance. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Jipu, Xiaolong Wei, Meiyan Wang, Xu Li, Bin Yan, Xiaotong Pan, Zhe Zhang, Yao Wu, Bofang Shi, and Honghui Yang. 2026. "Preparation of Fe/PANI/GF Composite and Study on Its Interfacial Evaporation Performance" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010024

APA StyleGuo, J., Wei, X., Wang, M., Li, X., Yan, B., Pan, X., Zhang, Z., Wu, Y., Shi, B., & Yang, H. (2026). Preparation of Fe/PANI/GF Composite and Study on Its Interfacial Evaporation Performance. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010024