Graphene-, Transition Metal Dichalcogenide-, and MXenes Material-Based Flexible Optoelectronic Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fundamental Properties of Key 2D Materials

2.1. Graphene

2.2. Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDs)

2.3. MXenes

3. Preparation Methods for 2D Materials

3.1. Top-Down Approaches

3.2. Bottom-Up Approaches

4. Applications in Flexible Optoelectronic Devices

4.1. Flexible Photodetectors

4.2. Flexible Light-Emitting Devices

4.3. Flexible Optical Modulators

4.4. Flexible Solar Cells

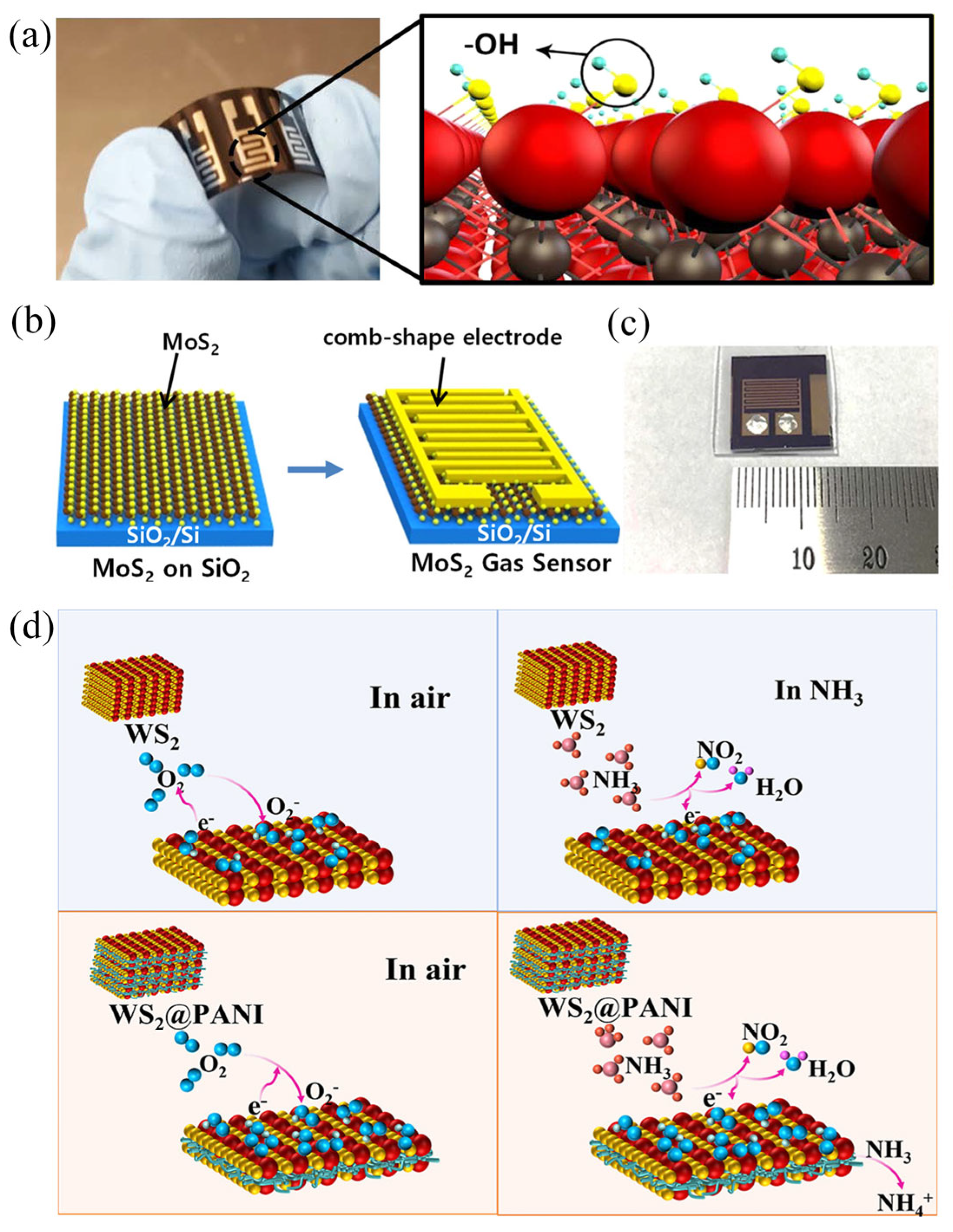

4.5. Flexible Gas Sensors

4.6. Substrate-Limited Compromise

4.7. Mechanical Reliability of Flexible Optoelectronic Devices

5. Summary and Perspectives

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, Z.; Shen, G. Flexible optoelectronic sensors: Status and prospects. Mater. Chem. Front. 2023, 7, 1496–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Kim, M.; Kim, I.; Lee, H. Flexible and stretchable optoelectronic devices using silver nanowires and graphene. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 4541–4548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Tong, B.; Yuan, S.; Dai, N.; Liu, R.; Zhang, D.; Cheng, H.M.; Ren, W. Advances in flexible optoelectronics based on chemical vapor deposition-grown graphene. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Wen, Z.; Sun, X. Recent Progress of Flexible Photodetectors Based on Low-Dimensional II–VI Semiconductors and Their Application in Wearable Electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2211548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Fu, H.; Tang, R.; Zhang, B.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, J. Failure mechanisms in flexible electronics. Int. J. Smart Nano Mater. 2023, 14, 510–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Cai, T.; Wu, B.; Hu, B.; Li, X.; Song, E.; Huang, G.; Tian, Z.; Di, Z. Recent Progress on Flexible Silicon Nanomembranes for Advanced Electronics and Optoelectronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, 35, 2502191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Chhowalla, M.; Liu, Z. 2D nanomaterials: Graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 3015–3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Mei, L.; Zhu, R.; Qin, J.; Hu, J.; Chen, Z.; Hau Ng, Y.; Voiry, D. 2D transition metal dichalcogenides for photocatalysis. Angew. Chem. 2023, 135, e202218016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.S.; Das, S.; Verzhbitskiy, I.A.; Huang, D.; Zhang, Y.; Talha-Dean, T.; Fu, W.; Venkatakrishnarao, D.; Johnson Goh, K.E. Dielectrics for two-dimensional transition-metal dichalcogenide applications. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 9870–9905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Alshareef, H.N. MXenes for optoelectronic devices. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 2100295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orts Mercadillo, V.; Chan, K.C.; Caironi, M.; Athanassiou, A.; Kinloch, I.A.; Bissett, M.; Cataldi, P. Electrically conductive 2D material coatings for flexible and stretchable electronics: A comparative review of graphenes and MXenes. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2204772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.; Wei, X.; Kysar, J.W.; Hone, J. Measurement of the elastic properties and intrinsic strength of monolayer graphene. Science 2008, 321, 385–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.F.; Sun, T.; Liu, Q.; Suo, Z.; Ren, Z. Highly stretchable and transparent nanomesh electrodes made by grain boundary lithography. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bertolazzi, S.; Brivio, J.; Kis, A. Stretching and breaking of ultrathin MoS2. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 9703–9709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.; Han, E.; Hossain, M.A.; Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Ertekin, E.; van der Zande, A.M.; Huang, P.Y. Designing the bending stiffness of 2D material heterostructures. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2007269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Deng, L.; Guo, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, X.; Luo, J. Bulk nanostructured materials design for fracture-resistant lithium metal anodes. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1807585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, T.; Zhou, D.; Deng, S.; Jafarpour, M.; Avaro, J.; Neels, A.; Heier, J.; Zhang, C. Rational design of Ti3C2Tx MXene inks for conductive, transparent films. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 3737–3749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, P.; Ma, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Samorì, P. Dressing AgNWs with MXenes nanosheets: Transparent printed electrodes combining high-conductivity and tunable work function for high-performance opto-electronics. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2412512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Kitchaev, D.A.; Lebens-Higgins, Z.; Vinckeviciute, J.; Zuba, M.; Reeves, P.J.; Grey, C.P.; Whittingham, M.S.; Piper, L.F.; Van der Ven, A. Pushing the limit of 3 d transition metal-based layered oxides that use both cation and anion redox for energy storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 522–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.; Zhou, Z.; Song, Q.; Chen, K.; Su, G.; Zhou, T.; Zheng, Z.; Lu, C.; Zhang, X. Ultrarobust Ti3C2Tx MXene-based soft actuators via bamboo-inspired mesoscale assembly of hybrid nanostructures. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 7055–7065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Amir, A.A.; Ohsawa, T.; Ishii, S.; Imura, M.; Segawa, H.; Sakaguchi, I.; Nagao, T.; Shimamura, K.; Ohashi, N. Optoelectronic characteristics of the Ag-doped Si pn photodiodes prepared by a facile thermal diffusion process. AIP Adv. 2019, 9, 055024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezeshki, A.; Shokouh, S.H.H.; Nazari, T.; Oh, K.; Im, S. Electric and photovoltaic behavior of a few-layer α-MoTe2/MoS2 dichalcogenide heterojunction. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 3216–3222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrini, N.; Peci, E.; Curreli, N.; Spotorno, E.; Kazemi Tofighi, N.; Magnozzi, M.; Scotognella, F.; Bisio, F.; Kriegel, I. Optimizing Gold-Assisted Exfoliation of Layered Transition Metal Dichalcogenides with (3-Aminopropyl) triethoxysilane (APTES): A Promising Approach for Large-Area Monolayers. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2024, 12, 2303228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo, A.D.R.; Pellegrini, V.; Ansaldo, A.; Ricciardella, F.; Sun, H.; Marasco, L.; Buha, J.; Dang, Z.; Gagliani, L.; Lago, E. High-yield production of 2D crystals by wet-jet milling. Mater. Horiz. 2018, 5, 890–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellani, S.; Petroni, E.; Del Rio Castillo, A.E.; Curreli, N.; Martín-García, B.; Oropesa-Nuñez, R.; Prato, M.; Bonaccorso, F. Scalable production of graphene inks via wet-jet milling exfoliation for screen-printed micro-supercapacitors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1807659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Liu, C.; Zhu, Q.; Su, X.; Qian, W.; Sun, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, B.; Chen, M.; Chen, L. An ultrasensitive molybdenum-based double-heterojunction phototransistor. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Y.; Liu, T.; Meng, B.; Li, X.; Liang, G.; Hu, X.; Wang, Q.J. Broadband high photoresponse from pure monolayer graphene photodetector. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.-K.; Zhang, W.; Lee, Y.H.; Lin, Y.C.; Chang, M.T.; Su, C.Y.; Chang, C.S.; Li, H.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H. Growth of large-area and highly crystalline MoS2 thin layers on insulating substrates. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 1538–1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honglai, L.; Xidong, D.; Xueping, W.; Xiujuan, Z.; Hong, Z.; Qinglin, Z.; Xiaoli, Z.; Wei, H.; Pinyun, R.; Pengfei, G. Growth of Alloy MoS2xSe2(1–x) Nanosheets with Fully Tunable Chemical Compositions and Optical Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3756–3759. [Google Scholar]

- Secor, E.B.; Prabhumirashi, P.L.; Puntambekar, K.; Geier, M.L.; Hersam, M.C. Inkjet printing of high conductivity, flexible graphene patterns. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 1347–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, K. Adhesion measurement of thin films. Act. Passiv. Electron. Compon. 1976, 3, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suk, J.W.; Kitt, A.; Magnuson, C.W.; Hao, Y.; Ahmed, S.; An, J.; Swan, A.K.; Goldberg, B.B.; Ruoff, R.S. Transfer of CVD-grown monolayer graphene onto arbitrary substrates. ACS Nano 2011, 5, 6916–6924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Yao, Q.; Huang, C.W.; Zou, X.; Liao, L.; Chen, S.; Fan, Z.; Zhang, K.; Wu, W.; Xiao, X. High Mobility MoS2 transistor with low Schottky barrier contact by using atomic thick h-BN as a tunneling layer. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 8302–8308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Wei, G.; Su, Z. Fabrication, material regulation, and healthcare applications of flexible photodetectors. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 12511–12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Koo, J.H.; Yoo, J.; Kim, M.S.; Choi, M.K.; Kim, D.H.; Song, Y.M. Flexible and stretchable light-emitting diodes and photodetectors for human-centric optoelectronics. Chem. Rev. 2024, 124, 768–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, S.; Huang, H. Defective photocathode: Fundamentals, construction, and catalytic energy conversion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33, 2304925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Bao, Z.; Pan, X.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Fan, H. Semimetal-enabled Rectenna for Sub-THz Wireless Energy Harvesting and Wave-mixing. Preprint 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaithambi, A.; Tofighi, N.K.; Ghini, M.; Curreli, N.; Schuck, P.J.; Kriegel, I. Energy transfer and charge transfer between semiconducting nanocrystals and transition metal dichalcogenide monolayers. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 7717–7730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Fazio, D.; Goykhman, I.; Yoon, D.; Bruna, M.; Eiden, A.; Milana, S.; Sassi, U.; Barbone, M.; Dumcenco, D.; Marinov, K.; et al. High Responsivity, Large-Area Graphene/MoS2 Flexible Photodetectors. Acs Nano 2016, 10, 8252–8262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.R.; Song, W.; Han, J.K.; Lee, Y.B.; Kim, S.J.; Myung, S.; Lee, S.S.; An, K.S.; Choi, C.J.; Lim, J. Wafer-scale, homogeneous MoS2 layers on plastic substrates for flexible visible-light photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 5025–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Verma, C.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Gupta, A.; Gupta, B. Silver nanoparticle-embedded nanogels for infection-resistant surfaces. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 8546–8556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Chai, J.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Guo, D.S.; Shi, L.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y. Calixarene-integrated nano-drug delivery system for tumor-targeted delivery and tracking of anti-cancer drugs in vivo. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 7295–7303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Dong, C.; Gui, Y.; Ye, J.; Altaleb, S.; Thomaschewski, M.; Movahhed Nouri, B.; Patil, C.; Dalir, H.; Sorger, V.J. Self-powered Sb2Te3/MoS2 heterojunction broadband photodetector on flexible substrate from visible to near infrared. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, S.; Luo, X.; Xu, S. Revealing the mechanism of VOx/Ti3AlC2 for the dehydrogenation of propane. New J. Chem. 2024, 48, 13743–13751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, C.W.; Shin, D.H.; Choi, S.H. Remarkable Enhancement of Detectivity and Stability in Flexible n–i–p-Type Perovskite Photodetectors by Concurrent Use of Various Two-Dimensional Materials: Doped Graphene, Graphene Quantum Dots, WS2, and h-BN. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2024, 6, 5517–5524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, M.C.; Lin, J.Y.; Chao, Y.C.; Ho, C.C.; Hsu, F.C.; Shen, J.L.; Chen, Y.F. An ultrathin, transparent, flexible, and self-powered photodetector based on two-dimensional materials and a self-assembled polar-monolayer. J. Mater. Chem. C 2025, 13, 14902–14909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.W.T.; Zhu, J.; Sangwan, V.K.; Secor, E.B.; Wallace, S.G.; Hersam, M.C. Fully Inkjet-Printed, Mechanically Flexible MoS2 Nanosheet Photodetectors. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 5675–5681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curreli, N.; Serri, M.; Spirito, D.; Lago, E.; Petroni, E.; Martín-García, B.; Politano, A.; Gürbulak, B.; Duman, S.; Krahne, R. Liquid phase exfoliated indium selenide based highly sensitive photodetectors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 1908427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curreli, N.; Serri, M.; Zappia, M.I.; Spirito, D.; Bianca, G.; Buha, J.; Najafi, L.; Sofer, Z.; Krahne, R.; Pellegrini, V. Liquid-phase exfoliated gallium selenide for light-driven thin-film transistors. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7, 2001080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappia, M.I.; Bianca, G.; Bellani, S.; Curreli, N.; Sofer, Z.k.; Serri, M.; Najafi, L.; Piccinni, M.; Oropesa-Nuñez, R.; Marvan, P. Two-dimensional gallium sulfide nanoflakes for UV-selective photoelectrochemical-type photodetectors. J. Phys. Chem. C 2021, 125, 11857–11866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianca, G.; Zappia, M.I.; Bellani, S.; Ghini, M.; Curreli, N.; Buha, J.; Galli, V.; Prato, M.; Soll, A.; Sofer, Z. Indium Selenide/Indium Tin Oxide Hybrid Films for Solution-Processed Photoelectrochemical-Type Photodetectors in Aqueous Media. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 10, 2201635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Ni, F.; Ouyang, W.; Fang, X. Bio-inspired transparent MXene electrodes for flexible UV photodetectors. Mater. Horiz. 2020, 7, 1828–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.; Tao, Y.; Dat, V.K.; Kim, J.H. Silicon photodiode-competitive 2D vertical photodetector. npj Flex. Electron. 2025, 9, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tang, X.; Jamal, R.; Abdiryim, T.; Xu, F.; Serkjan, N.; Wang, Y. Flexible self-powered ultraviolet photodetector based on the GQDs: Zinc oxide nanoflower heterojunction. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1017, 179201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Rogers, J.A. Recent advances in flexible inorganic light emitting diodes: From materials design to integrated optoelectronic platforms. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2019, 7, 1800936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, G.; Wang, S. Intrinsically stretchable electroluminescent materials and devices. CCS Chem. 2024, 6, 1360–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrzejewski, D.; Oliver, R.; Beckmann, Y.; Grundmann, A.; Heuken, M.; Kalisch, H.; Vescan, A.; Kümmell, T.; Bacher, G. Flexible Large-Area Light-Emitting Devices Based on WS2 Monolayers. Adv. Opt. Mater. 2020, 8, 2000694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.h.; Kim, J.Y.; Choi, S.; Lee, Y.; Lee, K.S.; Kim, J.; Joo, J. Photosensitive n-type doping using perovskite CsPbX3 quantum dots for two-dimensional MSe2 (M=Mo and W) field-effect transistors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 25159–25167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Choi, J.; Hwangbo, S.; Kwon, D.H.; Jang, B.; Ji, S.; Kim, J.H.; Han, S.K.; Ahn, J.H. Flexible micro-LED display and its application in Gbps multi-channel visible light communication. npj Flex. Electron. 2022, 6, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Zhuo, Z.; Liu, B.; Han, X.; Yang, J.; Sun, L.; Yang, Y.; Cai, J.; An, X.; Bai, L. Intrinsically stretchable fully π-conjugated polymers with inter-aggregate capillary interaction for deep-blue flexible inkjet-printed light-emitting diodes. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Tang, B.; Ye, K.; Hu, H.; Zhang, H. Ultra-Wide Modulation and Reversible Reconfiguration of a Flexible Organic Crystalline Optical Waveguide Between 645 and 731 nm. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2025, 64, e202417459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Tu, D.; Guan, H.; Tian, L.; Li, Z. 0.33 V· cm thin-film lithium niobate Mach-Zehnder modulator with ridge-top transparent electrode. Opt. Express 2025, 33, 41353–41363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paukov, M.I.; Starchenko, V.V.; Krasnikov, D.V.; Komandin, G.A.; Gladush, Y.G.; Zhukov, S.S.; Gorshunov, B.P.; Nasibulin, A.G.; Arsenin, A.V.; Volkov, V.S. Ultrafast optomechanical terahertz modulators based on stretchable carbon nanotube thin films. Ultrafast Sci. 2023, 3, 0021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Lee, J.; Seo, C.; Han, G.H.; Cho, B.W.; Kim, J.; Lee, Y.H.; Lee, H.S. Polymer-waveguide-integrated 2D semiconductor heterostructures for optical communications. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 11019–11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, B.; Lu, W.; Liu, Z.; Gao, S. Low-energy high-speed plasmonic enhanced modulator using graphene. Opt. Express 2018, 26, 7358–7367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, J.; Cheng, H.; Xu, L.; Fu, B.; Liu, X.; Zhang, H. Ag/MXene composite as a broadband nonlinear modulator for ultrafast photonics. ACS Photonics 2023, 10, 3133–3142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrentino, R.; Kozma, E.; Luzzati, S.; Po, R. Interlayers for non-fullerene based polymer solar cells: Distinctive features and challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 2021, 14, 180–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, S.; John, S. Beyond 30% conversion efficiency in silicon solar cells: A numerical demonstration. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, L.; Taheri, B.; Martín-García, B.; Bellani, S.; Di Girolamo, D.; Agresti, A.; Oropesa-Nunez, R.; Pescetelli, S.; Vesce, L.; Calabro, E. MoS2 quantum dot/graphene hybrids for advanced interface engineering of a CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite solar cell with an efficiency of over 20%. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 10736–10754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.Q.; Liu, L.Z.; Zhang, Z.L.; Liu, Y.F.; Gao, H.P.; Zhang, H.F.; Mao, Y.L. Surface modification with CuFeS2 nanocrystals to improve the efficiency and stability of perovskite solar cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 29178–29185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsikritzis, D.; Chatzimanolis, K.; Tzoganakis, N.; Bellani, S.; Zappia, M.I.; Bianca, G.; Curreli, N.; Buha, J.; Kriegel, I.; Antonatos, N. Two-dimensional BiTeI as a novel perovskite additive for printable perovskite solar cells. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2022, 6, 5345–5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrini, N.; Asaithambi, A.; Rebecchi, L.; Curreli, N. Bismuth telluride iodide monolayer flakes with nonlinear optical response obtained via gold-assisted mechanical exfoliation. Opt. Mater. X 2023, 19, 100255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebecchi, L.; Petrini, N.; Albo, I.M.; Curreli, N.; Rubino, A. Transparent conducting metal oxides nanoparticles for solution-processed thin films optoelectronics. Opt. Mater. X 2023, 19, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimipour, M.; Khazraei, S.; Kim, B.J.; Boschloo, G.; Johansson, E.M. Efficiency and stability enhancement of perovskite solar cells utilizing a thiol ligand and MoS2 (100) nanosheet surface modification. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2021, 4, 14080–14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimipour, M.; Khazraei, S.; Kim, B.J.; Boschloo, G.; Johansson, E.M. Efficient and bending durable flexible perovskite solar cells via interface modification using a combination of thin MoS2 nanosheets and molecules binding to the perovskite. Nano Energy 2022, 95, 107044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nirmal, K.A.; Ren, W.; Khot, A.C.; Kang, D.Y.; Dongale, T.D.; Kim, T.G. Flexible memristive organic solar cell using multilayer 2D titanium carbide MXene electrodes. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2300433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T.; Hamada, N.; Chantana, J.; Mavlonov, A.; Kawano, Y.; Masuda, T.; Minemoto, T. Application of two-dimensional MoSe2 atomic layers to the lift-off process for producing light-weight and flexible bifacial Cu (In, Ga) Se2 solar cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2020, 3, 9504–9508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akama, T.; Okita, W.; Nagai, R.; Li, C.; Kaneko, T.; Kato, T. Schottky solar cell using few-layered transition metal dichalcogenides toward large-scale fabrication of semitransparent and flexible power generator. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.H.; Jang, C.W.; Ko, J.S.; Choi, S.H. Enhancement of efficiency and stability in organic solar cells by employing MoS2 transport layer, graphene electrode, and graphene quantum dots-added active layer. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 538, 148155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, Y.W.; Jo, J.W.; Park, S.K.; Kim, J. Room-temperature gas sensors based on low-dimensional nanomaterials. J. Mater. Chem. C 2024, 12, 18609–18627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, P.; Guo, X.; Liao, X.; Liu, Y.; Cai, C.; Meng, X.; Wei, Z.; Du, G.; Shao, Y.; Nie, S. Advanced application of triboelectric nanogenerators in gas sensing. Nano Energy 2024, 126, 109672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.; Mohammadi, A.V.; Prorok, B.C.; Yoon, Y.S.; Beidaghi, M.; Kim, D.J. Room Temperature Gas Sensing of Two-Dimensional Titanium Carbide (MXene). ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 37184–37190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kang, S.K.; Oh, N.C.; Lee, H.D.; Lee, S.M.; Park, J.; Kim, H. Improved Sensitivity in Schottky Contacted Two-Dimensional MoS2 Gas Sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 38902–38909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Tang, C.L.; Song, H.J.; Zhang, L.B.; Lu, Y.B.; Huang, F.L. 1D/2D Heterostructured WS2@PANI Composite for Highly Sensitive, Flexible, and Room Temperature Ammonia Gas Sensor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 14082–14092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maji, B.; Badhulika, S. Fully flexible WSe2/V2C MXene heterostructure-based gas sensor: A detailed sensing analysis for ppb level detection of ammonia at room temperature. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1017, 179079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Device Description | Core Active Material | Responsivity (mA W−1) | Bending |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrathin self-powered transparent photodetector [46] | All 2D material stack | 1.58 | 150 bending cycles |

| Inkjet-printed flexible photodetector [47] | MoS2 nanosheets | >50 | >500 bending cycles |

| Large-area graphene/MoS2 heterostructure photodetector [39] | MoS2 | ~1011 | On flexible PET substrate |

| Liquid-exfoliated InSe based highly sensitive photodetector [48] | Liquid-exfoliated InSe nanoflakes | ~107 | _ |

| 2D Vertical Photodetector competitive with Si [53] | Ti/WSe2/Ag vertical stack | 200 | 5 mm |

| Flexible Self-powered UV Photodetector [54] | ZnO/GQDs heterojunction | 254.8 | 10 mm |

| Device Description | Emission Mechanism | Active Material | Emission Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large-area WS2 Monolayer LED [57] | EL | WS2 monolayer | Red |

| QD-2D MSe2 Hybrid Device [58] | PL | MSe2 | Green/Blue |

| Intrinsically Stretchable PLED [56] | EL | Polymer:PEI | _ |

| Flexible Blue Micro-LED Array [59] | EL | InGaN/GaN | Blue |

| Stretchable PLED with 2D Additive [60] | EL | Polymer/2D Material Composite | Deep Blue |

| Device Description | Modulation Rate/Bandwidth | Operating Wavelength/Band | Modulation Depth/Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stretchable CNT Terahertz Modulator [64] | ~2 × 10−13 s | 0.3–2.0 THz | >50% (at 0.3–2.0 THz) |

| Polymer-Waveguide-Integrated 2D Heterojunction Device [65] | Rise: ~8 × 10−6 s, Fall: ~1.5 × 10−5 s | 660 nm | 5.8 dB (at 660 nm) |

| Plasmonic-Enhanced Graphene Modulator [63] | 3-dB Bandwidth: 4 × 1011 Hz | ~1550 nm | _ |

| Ag/MXene Composite Modulator [66] | Nonlinear Saturable Absorption | Broadband | ~10.3% |

| Device Type | Core 2D Material | Power Conversion Efficiency (PCE) | Fabrication Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perovskite solar cell [76] | MXene Transparent Electrode | 13.86% | Solution processing |

| CIGS Thin-Film Solar Cell [77] | TMDs Release Layer | 11.5% | Vapor deposition |

| TMDs Schottky Solar Cell [78] | TMDs Active Layer | ~0.7% | CVD growth |

| High-Efficiency Flexible Cell [68] | Graphene Transparent Electrode | >18% | CVD transfer |

| Perovskite Solar Cell [69] | TMDs Interface Engineering | >20% | Solution processing |

| Flexible Organic Solar Cell [79] | MoS2 hole transport layer, Graphene electrode | 4.23% | Spin-coating |

| Device Description | Core 2D Material | Target Gas | Response/Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly Responsive Flexible Heterojunction Sensor [82] | Ti3C2Tx MXene | Acetone | Not specified |

| Schottky-barrier engineered FET sensor [83] | Few-layer MoS2 | NO2 | Response to NO2 enhanced by ~3× (after barrier tuning) |

| Room-Temperature Multi-Gas Sensor [84] | WS2 nanosheets | NH3 | ~216.3% (to 100 ppm) |

| MXene/TMDs Heterojunction Sensor [85] | WSe2/V2C MXene heterostructure | NH3 | Not specified |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Zhou, G.; Zhang, Z.; Zhu, Z. Graphene-, Transition Metal Dichalcogenide-, and MXenes Material-Based Flexible Optoelectronic Devices. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010025

Wang Y, Zhou G, Zhang Z, Zhu Z. Graphene-, Transition Metal Dichalcogenide-, and MXenes Material-Based Flexible Optoelectronic Devices. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010025

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yingying, Geyi Zhou, Zhisheng Zhang, and Zhihong Zhu. 2026. "Graphene-, Transition Metal Dichalcogenide-, and MXenes Material-Based Flexible Optoelectronic Devices" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010025

APA StyleWang, Y., Zhou, G., Zhang, Z., & Zhu, Z. (2026). Graphene-, Transition Metal Dichalcogenide-, and MXenes Material-Based Flexible Optoelectronic Devices. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010025