Three-Dimensional Chiral Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthesis and Structural Transformations

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Instruments and Methods

2.2. X-Ray Crystallography

2.3. Synthesis of Metal–Organic Coordination Polymers

2.4. Liquid-Phase Separation Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

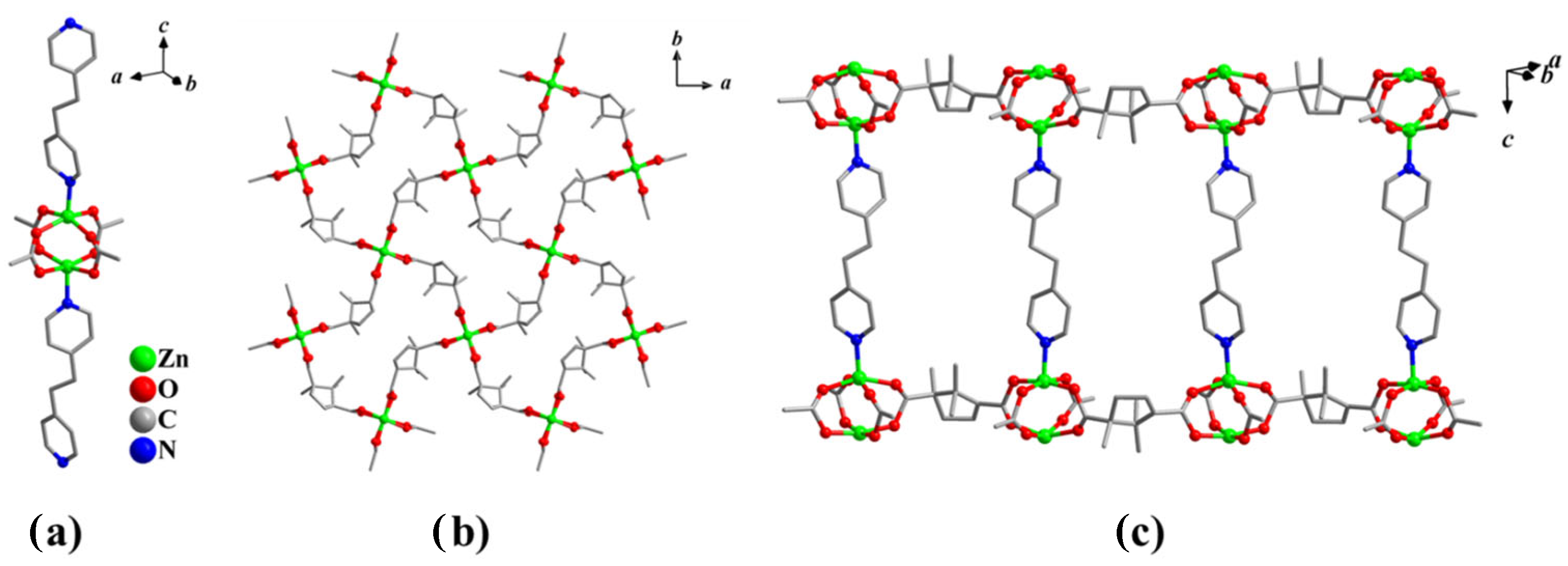

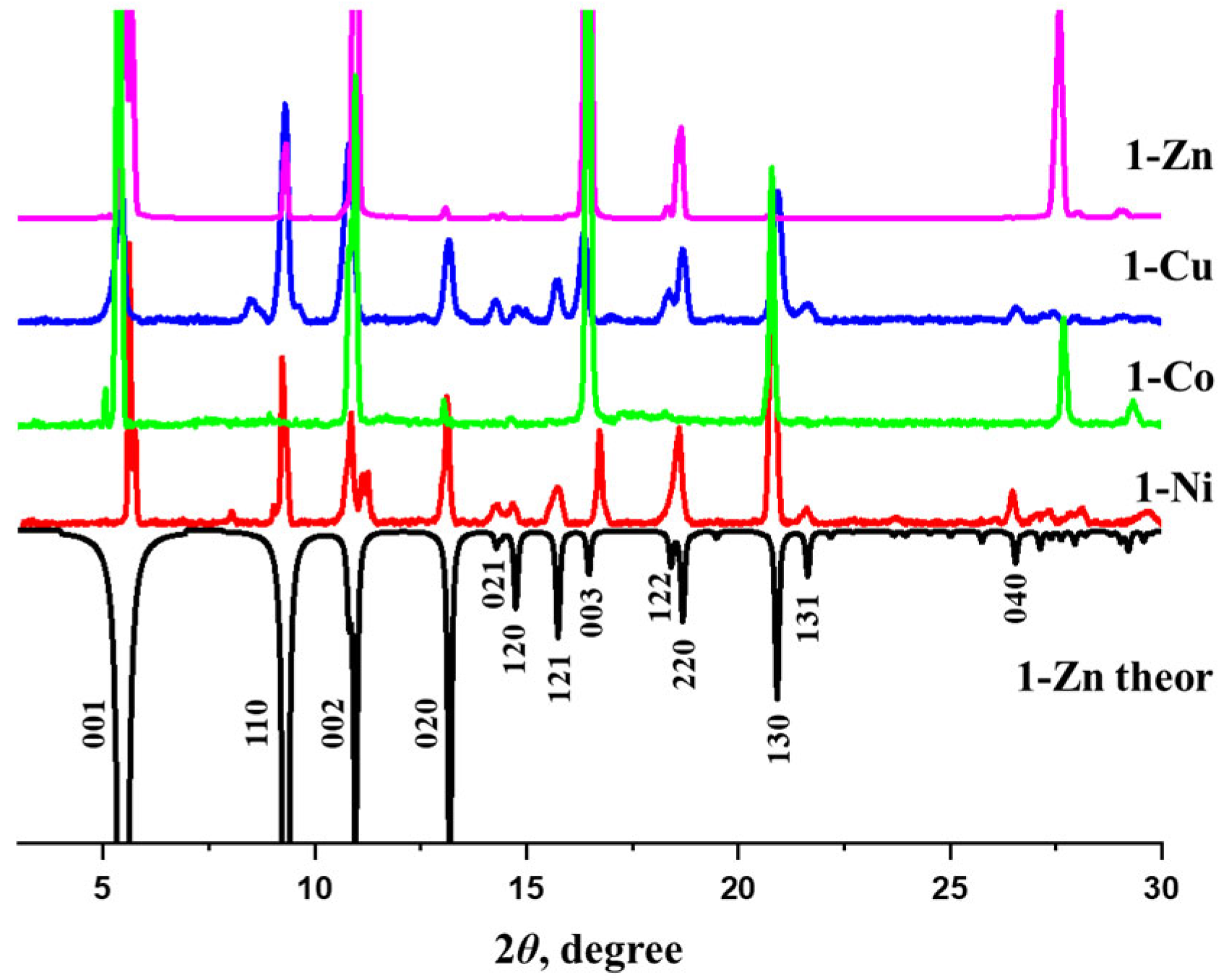

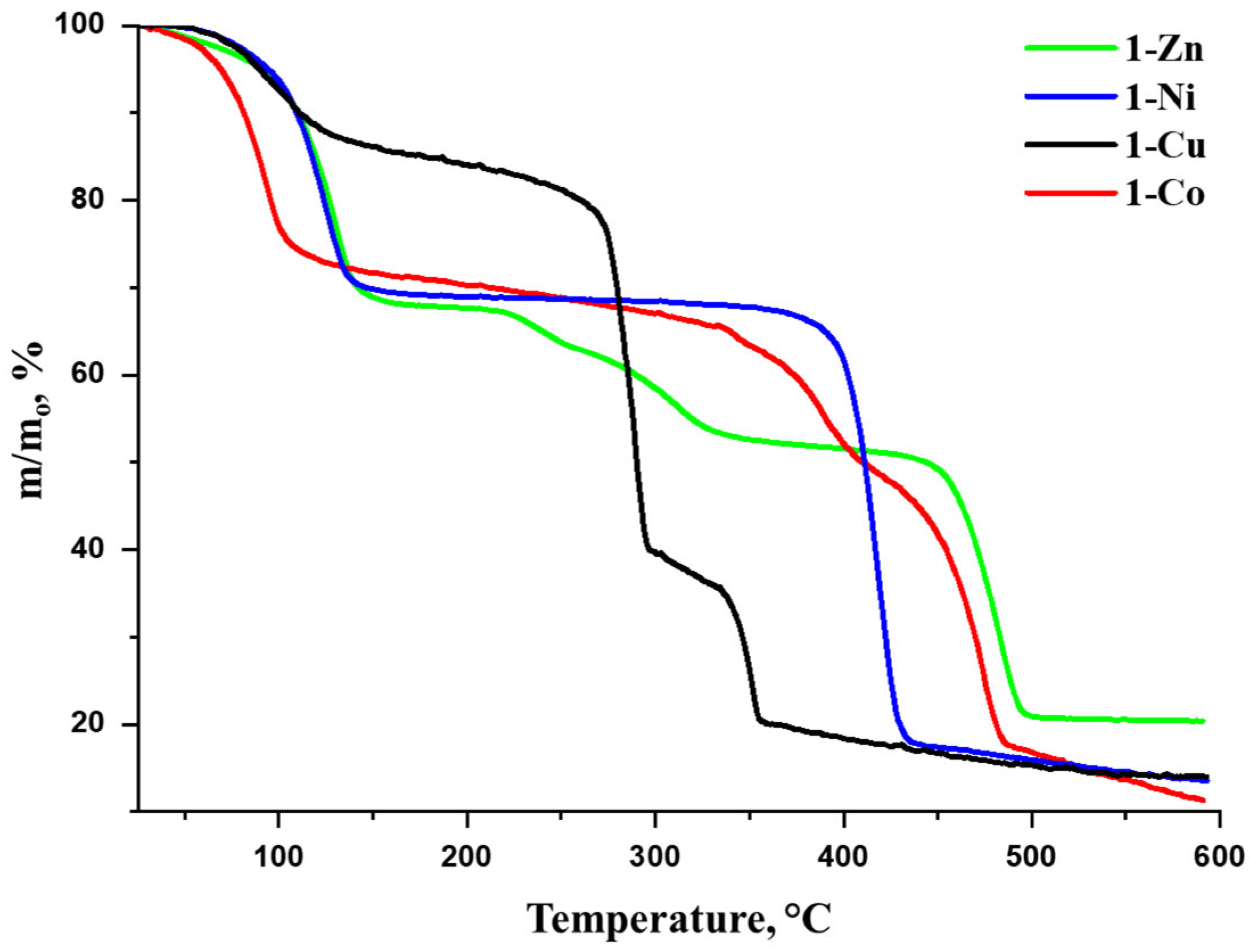

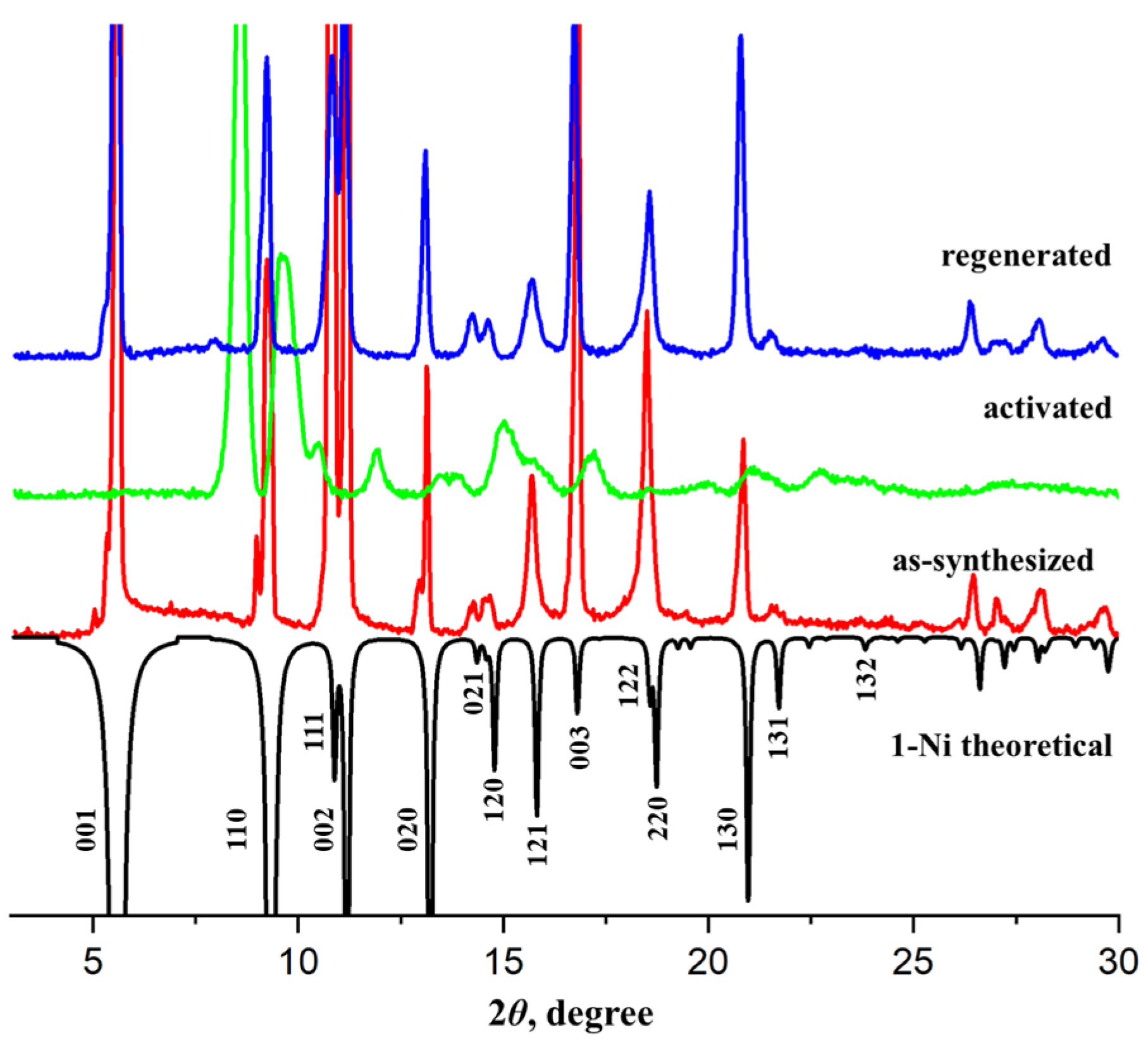

3.1. Characterization of the Compounds

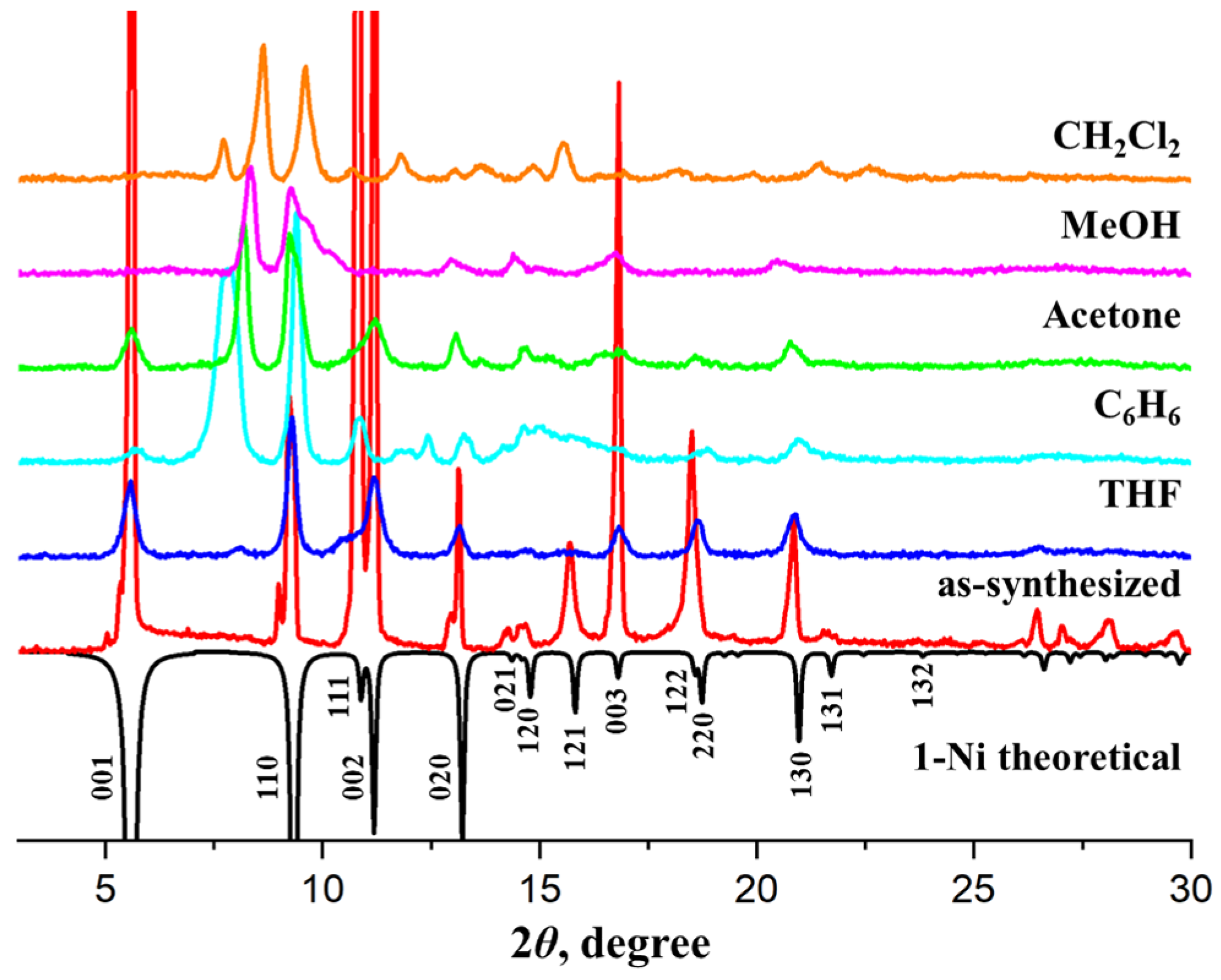

3.2. Structural Transformations

3.3. Adsorption Studies

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Seo, J.; Whang, D.; Lee, H.; Jun, S.I.; Oh, J.; Jeon, Y.J.; Kim, K. A homochiral metal-organic porous material for enantioselective separation and catalysis. Nature 2000, 404, 982–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kepert, C.J.; Prior, T.J.; Rosseinsky, M.J. A Versatile Family of Interconvertible Microporous Chiral Molecular Frameworks: The First Example of Ligand Control of Network Chirality. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 5158–5168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, L.; Lin, W. Chirality-Controlled and Solvent-Templated Catenation Isomerism in Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13834–13835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, A.; Tepaske, M.A.; Tanase, S. Homochiral metal–organic frameworks as heterogeneous catalysts. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2018, 5, 1512–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, M.; Chen, J.; Liu, H.; Huang, Z.; Huang, F.; Li, Q.; Xu, Y. A review on chiral metal–organic frameworks: Synthesis and asymmetric applications. Nanoscale 2022, 14, 13405–13427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Lou, L.-L.; Yu, K.; Liu, S. Advances in Chiral Metal–Organic and Covalent Organic Frameworks for Asymmetric Catalysis. Small 2021, 17, 2005686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacchioni, G. A chiral supramolecular MOF for enantiomer separation. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2023, 8, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, M. Emerging frontiers in chiral metal–organic framework membranes: Diverse synthesis techniques and applications. Nanoscale 2025, 17, 13076–13093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Wang, F.; Fischer, R.A.; Zhang, J. Homochiral metal–organic frameworks for enantioseparation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 5706–5745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kesanli, B.; Lin, W. Chiral porous coordination networks: Rational design and applications in enantioselective processes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2003, 246, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Lin, W. Homochiral BINOL-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks for Luminescence Sensing of Hydrobenzoin Enantiomers. Inorg. Chem. 2025, 64, 2583–2589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Song, B.-Q.; Sensharma, D.; Gao, M.-Y.; Bezrukov, A.A.; Nikolayenko, V.I.; Lusi, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Zaworotko, M.J. Effect of Extra-Framework Anion Substitution on the Properties of a Chiral Crystalline Sponge. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 8139–8146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, Q.; Ma, Q.; Li, X.; Zhao, L.; Sun, X. A chiral metal-organic framework {(HQA)(ZnCl2)(2.5H2O)}n for the enantioseparation of chiral amino acids and drugs. J. Pharm. Anal. 2023, 13, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, A.; Strudwick, B.; Dawson, D.M.; Ashbrook, S.E.; Woutersen, S.; Dubbeldam, D.; Tanase, S. Synthesis of Chiral MOF-74 Frameworks by Post-Synthetic Modification by Using an Amino Acid. Chem. Eur. J. 2020, 26, 13957–13965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Han, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhou, J.; Duan, P. Multi-Light-Responsive Upconversion-and-Downshifting-Based Circularly Polarized Luminescent Switches in Chiral Metal–Organic Frameworks. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2101797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Liu, Y.; Han, Y.; Cui, Y. Single-Crystalline Ultrathin 2D Porous Nanosheets of Chiral Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 3509–3518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, W.; Chen, X.; Fahy, K.M.; Dong, J.; Liu, Y.; Farha, O.K.; Cui, Y. Reticular Chemistry in Its Chiral Form: Axially Chiral Zr(IV)-Spiro Metal–Organic Framework as a Case Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145, 13869–13878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behera, N.; Duan, J.; Jin, W.; Kitagawa, S. The Chemistry and Applications of Flexible Porous Coordination Polymers. EnergyChem 2021, 3, 100067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.-Y.; Fairen-Jimenez, D.; Zaworotko, M.J. Structural Elucidation of the Mechanism of Molecular Recognition in Chiral Crystalline Sponges. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 17600–17606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demakov, P.A.; Poryvaev, A.S.; Kovalenko, K.A.; Samsonenko, D.G.; Fedin, M.V.; Fedin, V.P.; Dybtsev, D.N. Structural Dynamics and Adsorption Properties of the Breathing Microporous Aliphatic Metal–Organic Framework. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 15724–15732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Song, B.-Q.; Lusi, M.; Bezrukov, A.A.; Haskins, M.M.; Gao, M.-Y.; Peng, Y.-L.; Ma, J.-G.; Cheng, P.; Mukherjee, S.; et al. Crystal Engineering of a Chiral Crystalline Sponge That Enables Absolute Structure Determination and Enantiomeric Separation. Cryst. Growth Des. 2023, 23, 5211–5220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demakov, P.A.; Ryadun, A.A.; Dybtsev, D.N. Highly Luminescent Crystalline Sponge: Sensing Properties and Direct X-ray Visualization of the Substrates. Molecules 2022, 27, 8055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybtsev, D.N.; Nuzhdin, A.L.; Chun, H.; Bryliakov, K.P.; Talsi, E.P.; Fedin, V.P.; Kim, K. A Homochiral Metal–Organic Material with Permanent Porosity, Enantioselective Sorption Properties, and Catalytic Activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006, 45, 916–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybtsev, D.N.; Yutkin, M.P.; Samsonenko, D.G.; Fedin, V.P.; Nuzhdin, A.L.; Bezrukov, A.A.; Bryliakov, K.P.; Talsi, E.P.; Belosludov, R.V.; Mizuseki, H.; et al. Modular, Homochiral, Porous Coordination Polymers: Rational Design, Enantioselective Guest Exchange Sorption and Ab Initio Calculations of Host–Guest Interactions. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 10348–10356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dybtsev, D.N.; Yutkin, M.P.; Peresypkina, E.V.; Virovets, A.V.; Serre, C.; Férey, G.; Fedin, V.P. Isoreticular Homochiral Porous Metal–Organic Structures with Tunable Pore Sizes. Inorg. Chem. 2007, 46, 6843–6845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dybtsev, D.N.; Yutkin, M.P.; Fedin, V.P. Copper(II) camphorates with tunable pore size in metal-organic frameworks. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2009, 58, 2246–2249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker Apex3 Software Suite: Apex3, SADABS-2016/2 and SAINT; Version 2018.7-2; Bruker AXS Inc.: Madison, WI, USA, 2017.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT–Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spek, A.L. PLATON SQUEEZE: A tool for the calculation of the disordered solvent contribution to the calculated structure factors. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. C 2015, 71, 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezuidenhout, C.X.; Smith, V.J.; Esterhuysen, C.; Barbour, L.J. Solvent- and Pressure-Induced Phase Changes in Two 3D Copper Glutarate-Based Metal–Organic Frameworks via Glutarate (+gauche ⇄ −gauche) Conformational Isomerism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139, 5923–5929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-C.; Huh, S.; Kim, J.Y.; Moon, H.R.; Lee, D.N.; Kim, Y. Zn-MOFs containing flexible α,ω-alkane (or alkene)-dicarboxylates with 1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethylene: Comparison with Zn-MOFs containing 1,2-bis(4-pyridyl)ethane ligands. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahier, T.; Oliver, C.L. A Cd mixed-ligand MOF showing ligand-disorder induced breathing behaviour at high temperature and stepwise, selective carbon dioxide adsorption at low temperature. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 3607–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, S.; Sensharma, D.; Qazvini, O.T.; Dutta, S.; Macreadie, L.K.; Ghosh, S.K.; Babarao, R. Advances in adsorptive separation of benzene and cyclohexane by metal-organic framework adsorbents. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 437, 213852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, L.; Wu, Z.-H.; Ma, J.-P.; Wu, X.-W.; Dong, Y.-B. Adsorption and Separation of Organic Six-Membered Ring Analogues on Neutral Cd(II)-MOF Generated from Asymmetric Schiff-Base Ligand. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 11164–11173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.-H.; Tan, Y.-X.; He, Y.-P.; Yin, Z.; Chen, Q.; Kurmoo, M. A Porous 4-Fold-Interpenetrated Chiral Framework Exhibiting Vapochromism, Single-Crystal-to-Single-Crystal Solvent Exchange, Gas Sorption, and a Poisoning Effect. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 2353–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-H.; Luo, D.; Li, M.; Li, D. Local Deprotonation Enables Cation Exchange, Porosity Modulation, and Tunable Adsorption Selectivity in a Metal–Organic Framework. Cryst. Growth Des. 2017, 17, 3387–3394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Wang, Y.M.; Quan, M.; Farooq, M.U.; Yang, L.P.; Jiang, W. Adsorptive separation of benzene, cyclohexene, and cyclohexane by amorphous nonporous amide naphthotube solids. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 19945–19950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Hu, D.Y.; Liang, Z.-J.; Zhou, M.Y.; Wang, Z.-S.; Su, W.-Y.; Lin, R.-B.; Zhou, D.-D.; Zhang, J.-P. A metal azolate framework with small aperture for highly efficient ternary benzene/cyclohexene/cyclohexane separation. Chin. J. Struct. Chem. 2025, 44, 100540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Y.; Bailey, J.; Wang, Z.; Lee, D.; Sheveleva, A.M.; Tuna, F.; McInnes, E.J.L.; Frogley, M.D.; et al. Control of the pore chemistry in metal-organic frameworks for efficient adsorption of benzene and separation of benzene/cyclohexane. Chem 2023, 9, 739–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysova, A.A.; Samsonenko, D.G.; Dorovatovskii, P.V.; Lazarenko, V.A.; Khrustalev, V.N.; Kovalenko, K.A.; Dybtsev, D.N.; Fedin, V.P. Tuning the molecular and cationic affinity in a series of multifunctional metal–organic frameworks based on dodecanuclear Zn(II) carboxylate wheels. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 17260–17269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapianik, A.A.; Kovalenko, K.A.; Samsonenko, D.G.; Barsukova, M.O.; Dybtsev, D.N.; Fedin, V.P. Exceptionally effective benzene/cyclohexane separation using a nitro-decorated metal–organic framework. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 8241–8244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poryvaev, A.S.; Yazikova, A.A.; Polyukhov, D.M.; Fedin, M.V. Ultrahigh selectivity of benzene/cyclohexane separation by ZIF-8 framework: Insights from spin-probe EPR spectroscopy. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022, 330, 111564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Dubskikh, V.A.; Lysova, A.A.; Samsonenko, D.G.; Kovalenko, K.A.; Dybtsev, D.N.; Fedin, V.P. Three-Dimensional Chiral Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthesis and Structural Transformations. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010022

Dubskikh VA, Lysova AA, Samsonenko DG, Kovalenko KA, Dybtsev DN, Fedin VP. Three-Dimensional Chiral Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthesis and Structural Transformations. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010022

Chicago/Turabian StyleDubskikh, Vadim A., Anna A. Lysova, Denis G. Samsonenko, Konstantin A. Kovalenko, Danil N. Dybtsev, and Vladimir P. Fedin. 2026. "Three-Dimensional Chiral Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthesis and Structural Transformations" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010022

APA StyleDubskikh, V. A., Lysova, A. A., Samsonenko, D. G., Kovalenko, K. A., Dybtsev, D. N., & Fedin, V. P. (2026). Three-Dimensional Chiral Metal–Organic Frameworks: Synthesis and Structural Transformations. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010022