Eco-Friendly ZnO Nanomaterial Coatings for Photocatalytic Degradation of Emerging Organic Pollutants in Water Systems: Characterization and Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

2.2. Preparation of the Coatings

2.3. Coatings Characterization Techniques

2.4. Photodegradation Procedure

2.5. Photocatalyst Reutilization

2.6. Analytical Procedures

3. Results

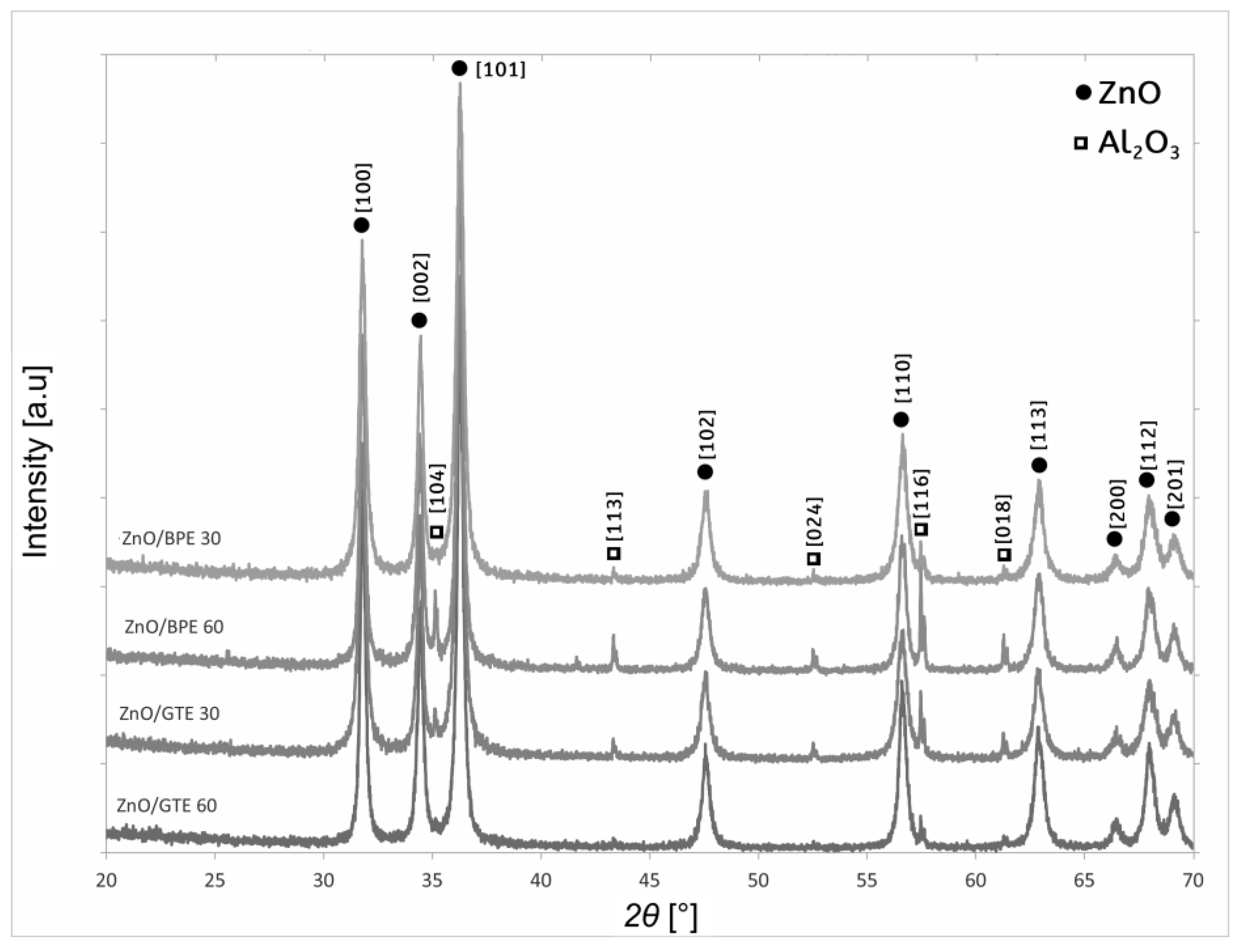

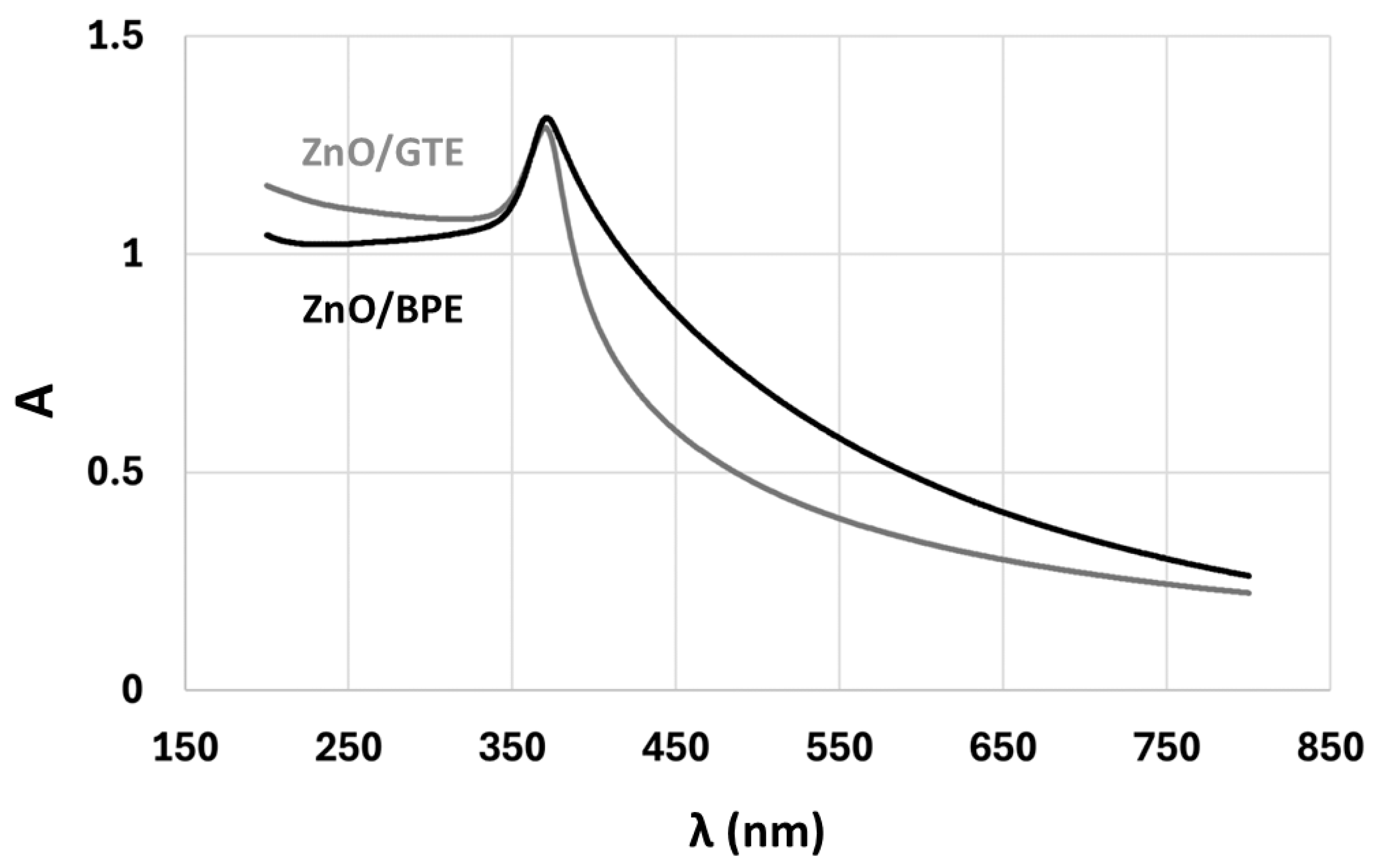

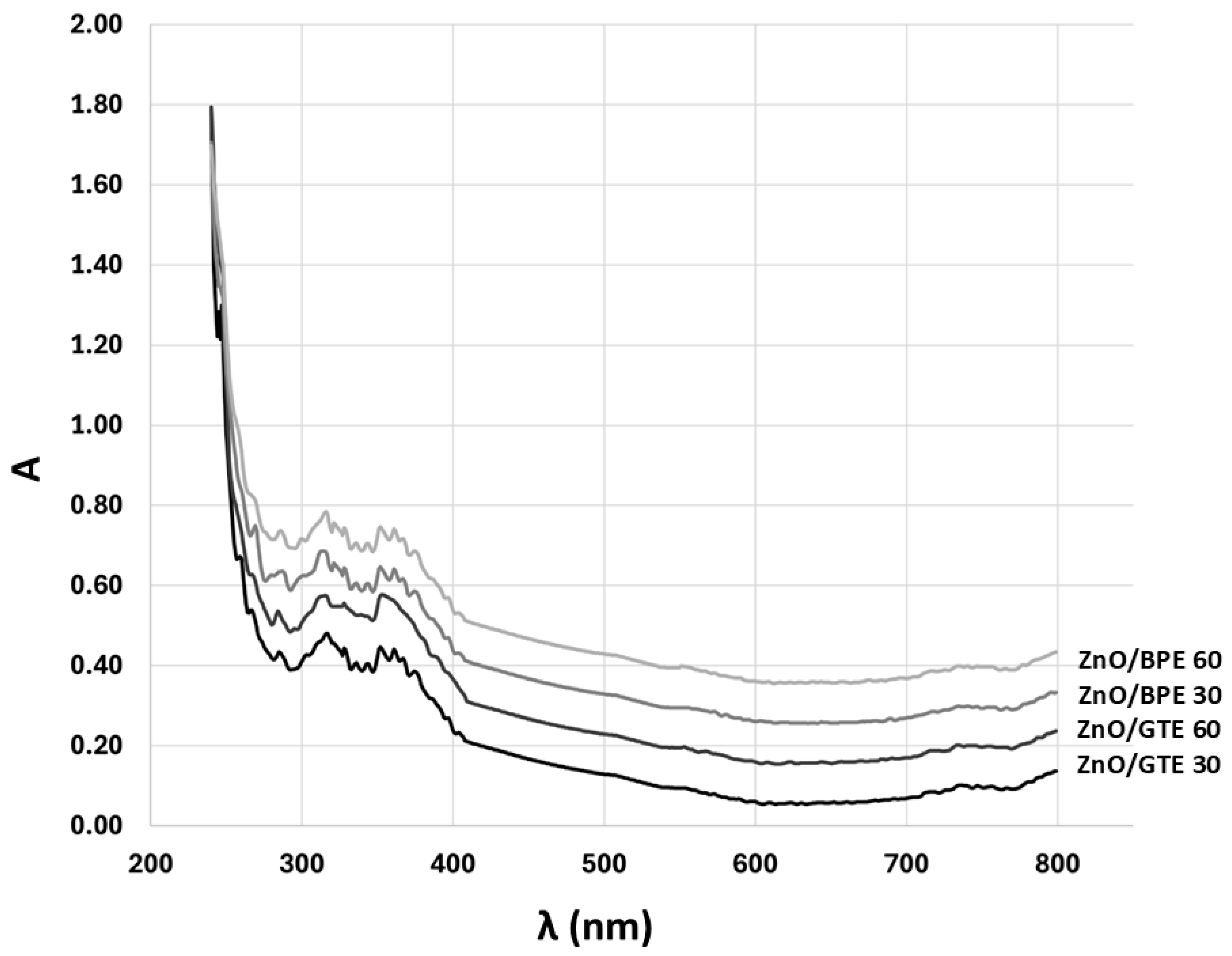

3.1. Characterization of the Coatings

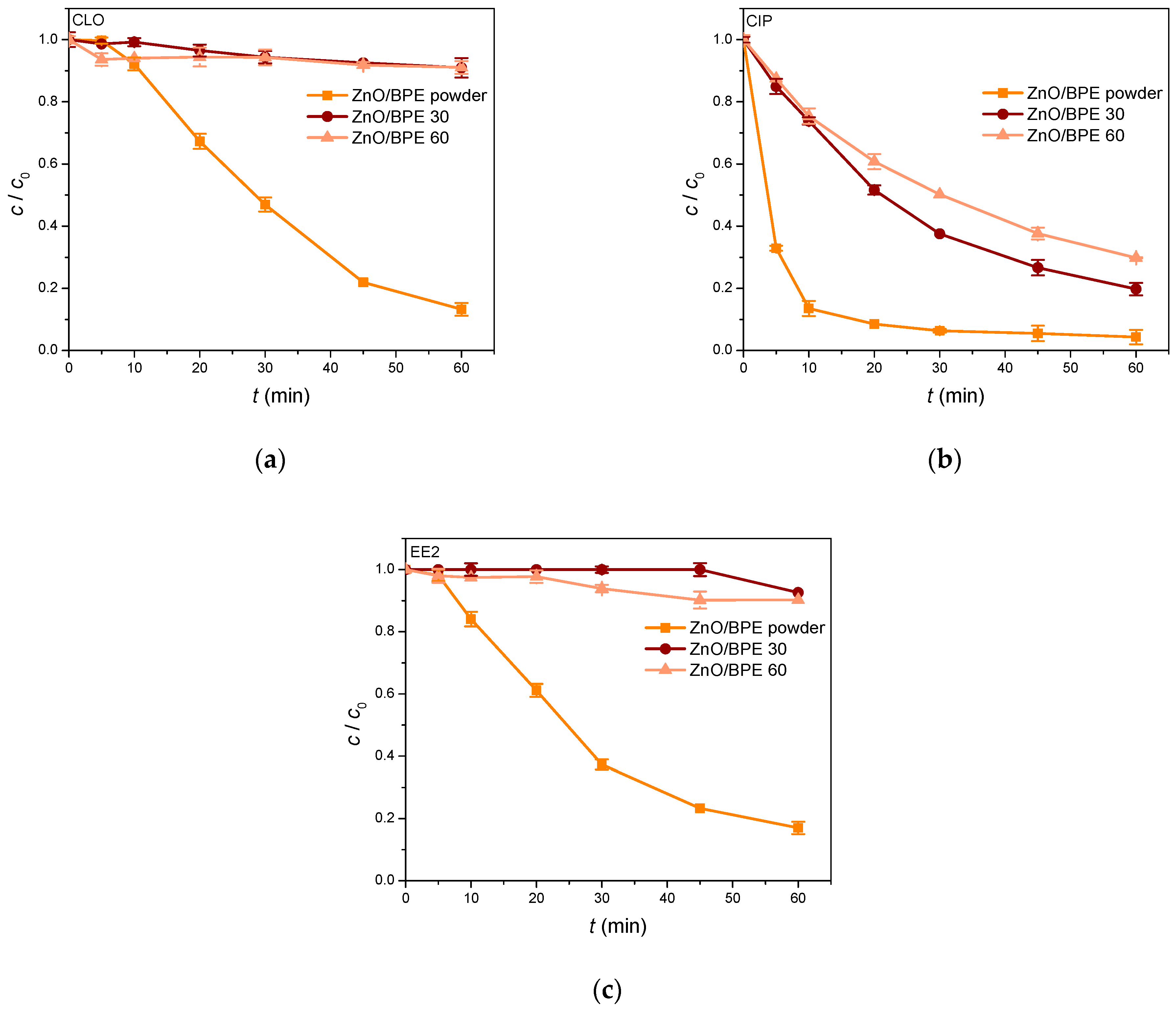

3.2. Photocatalytic Activity of ZnO/BPE Coatings

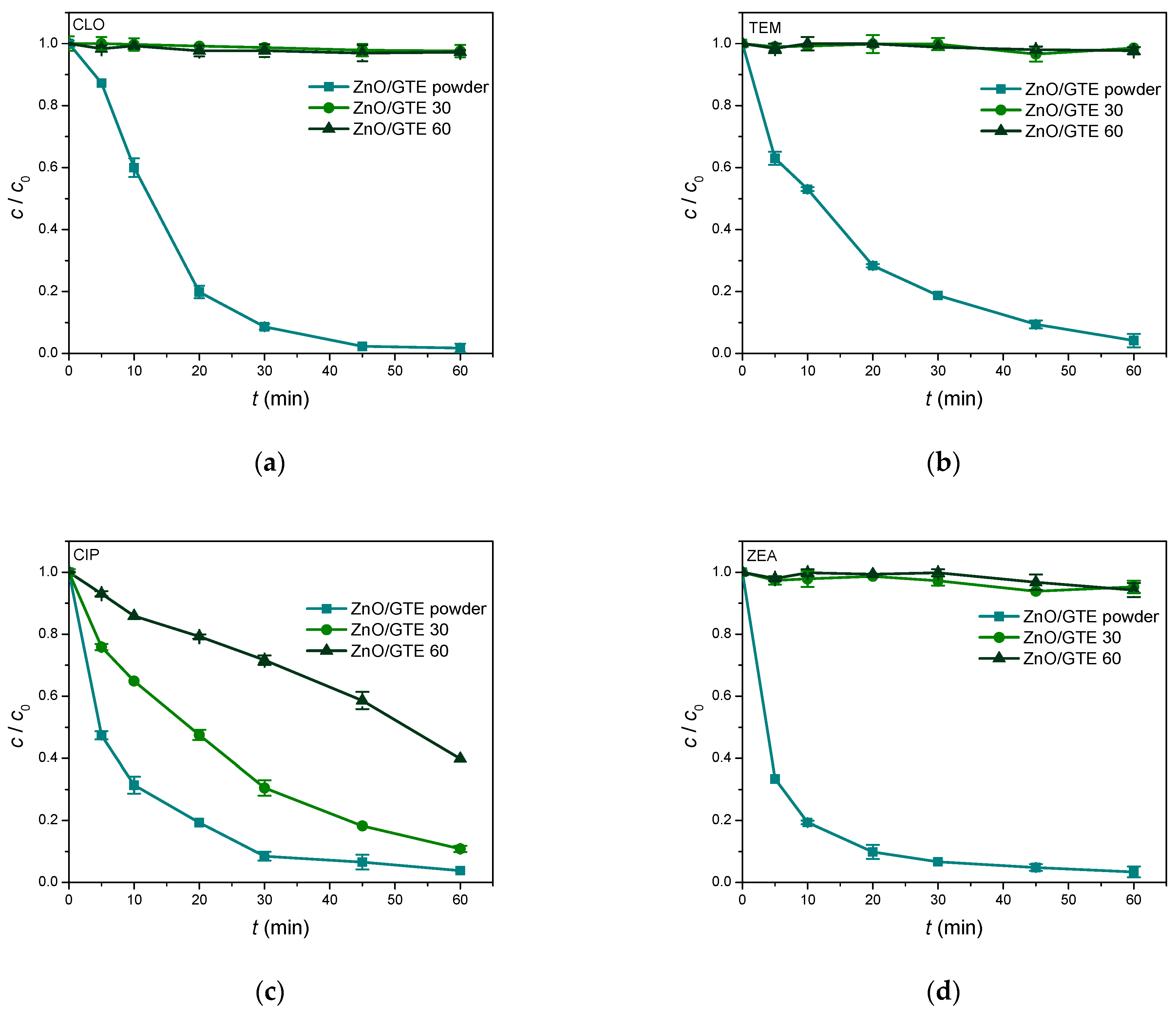

3.3. Photocatalytic Activity of ZnO/GTE Coatings

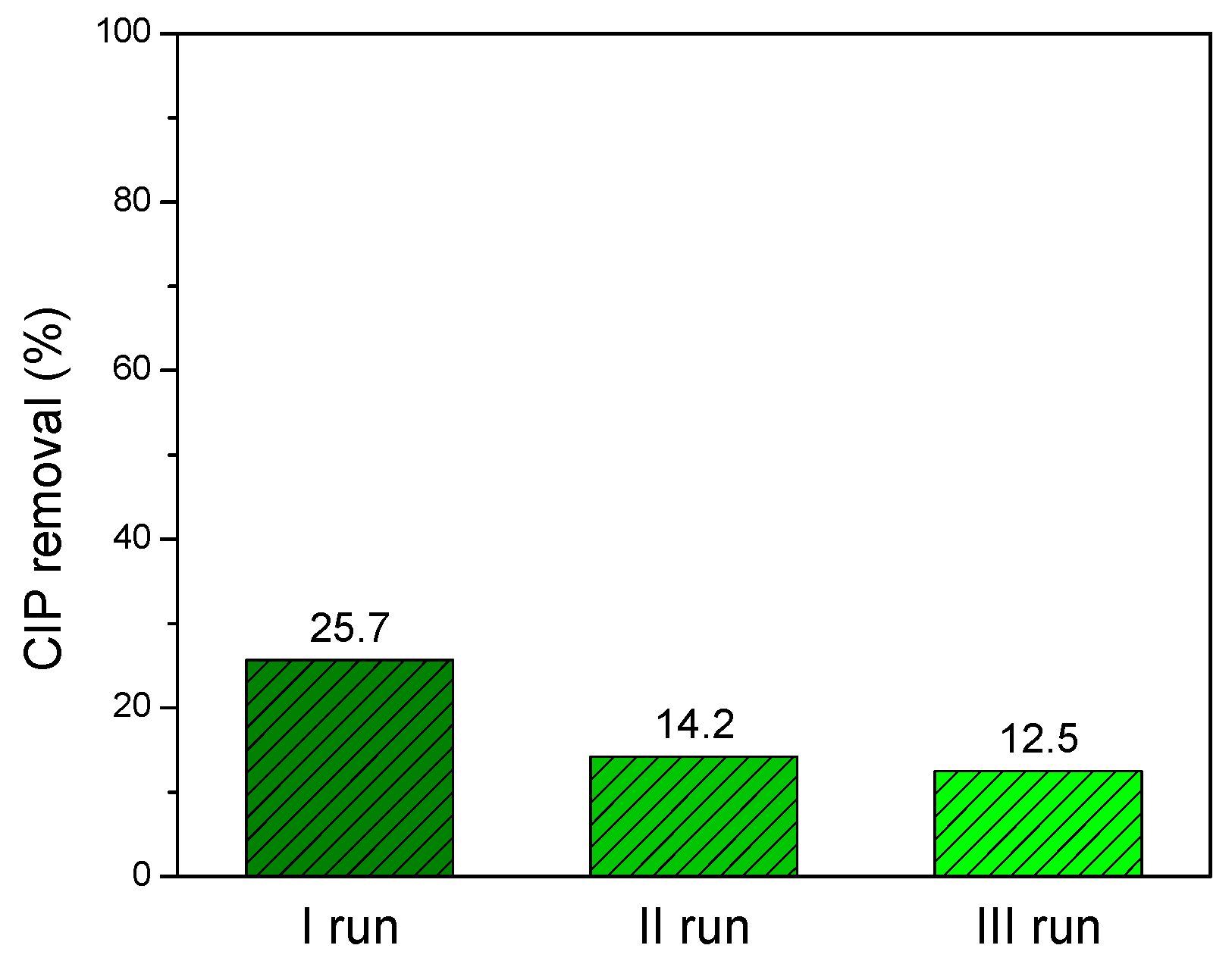

3.4. Reutilization of ZnO/GTE 30 Coating

4. Conclusions and Outlooks

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Statista: Global Environmental Pollution—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/4739/environmental-pollution/ (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Liu, Z.; Roosh, M.; Lu, M.; Arshad, A.; Xian, W.; Shen, Y.; Liu, G.; Bahadur, A.; Iqbal, S.; Mahmood, S.; et al. Empowering wastewater treatment with step scheme heterojunction ternary nanocomposites for photocatalytic degradation of nitrophenol. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.; Anwar, F.; Ghazali, F.M. A comprehensive review of mycotoxins: Toxicology, detection, and effective mitigation approaches. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Scoy, A.R.; Tjeerdema, R.S. Environmental fate and toxicology of clomazone. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2014, 229, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, P.; Wu, X.; Xu, J.; Dong, F.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Clomazone influence soil microbial community and soil nitrogen cycling. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 644, 475–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, S.; Jovanović, D.; Putnik, P.; Despotović, V.; Ivetić, T.; Bajac, B.; Tóth, E.; Finčur, N.; Maksimović, I.; Putnik-Delić, M.; et al. Solar-driven removal of selected organics with binary ZnO based nanomaterials from aquatic environment: Chemometric and toxicological assessments on wheat. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 112016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barchanska, H.; Kluza, A.; Krajczewska, K.; Maj, J. Degradation study of mesotrione and other triketone herbicides on soils and sediments. J. Soils Sediments 2015, 16, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarević, M.; Putnik, P.; Šojić Merkulov, D. Chemometric evaluation of different parameters for removal of tembotrione (agricultural herbicide) from water by adsorption and photocatalytic degradation using sustainable nanotechnology. Food Energy Secur. 2022, 11, e368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Wen, S.; Shi, T.; Li, Q.X.; Lv, P.; Hua, R. Photocatalysis of the triketone herbicide tembotrione in water with bismuth oxychloride nanoplates: Reactive species, kinetics and pathways. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, M.; Langer, O.; Dobrozemsky, G.; Muller, U.; Zeitlinger, M.; Mitterhauser, M.; Wadsak, W.; Dudczak, R.; Kletter, K.; Muller, M. [18F]Ciprofloxacin, a new positron emission tomography tracer for noninvasive assessment of the tissue distribution and pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in humans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004, 48, 3850–3857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopanna, M.; Mangalgiri, K.; Ibitoye, T.; Ocasio, D.; Snowberger, S.; Blaney, L. UV-254 transformation of antibiotics in water and wastewater treatment processes. In Contaminants of Emerging Concern in Water and Wastewater: Advanced Treatment Processes; Hernández-Maldonado, A.J., Blaney, L., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann Elsevier Inc.: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 239–297. [Google Scholar]

- Naslund, J.; Hedman, J.E.; Agestrand, C. Effects of the antibiotic ciprofloxacin on the bacterial community structure and degradation of pyrene in marine sediment. Aquat. Toxicol. 2008, 90, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cappelli, F.; Longoni, O.; Rigato, J.; Rusconi, M.; Sala, A.; Fochi, I.; Palumbo, M.T.; Polesello, S.; Roscioli, C.; Salerno, F.; et al. Suspect screening of wastewaters to trace anti-COVID-19 drugs: Potential adverse effects on aquatic environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 824, 153756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez-Garcia, P.; Rodriguez, R.R.; Barata, C.; Gomez-Canela, C. Presence and toxicity of drugs used to treat SARS-CoV-2 in Llobregat River, Catalonia, Spain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 49487–49497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Dai, X.; Liu, Y.; Sun, J.; Song, S.; Ni, B.J. Model-based assessment of estrogen removal by nitrifying activated sludge. Chemosphere 2018, 197, 430–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aoki, J.Y.; Hatsuyama, A.; Hiramatsu, N.; Soyano, K. Effects of ethynylestradiol on vitellogenin synthesis and sex differentiation in juvenile grey mullet (Mugil cephalus) persist after long-term exposure to a clean environment. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part-C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2011, 154, 346–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyhanian, N.; Volkova, K.; Hallgren, S.; Bollner, T.; Olsson, P.E.; Olsen, H.; Hallstrom, I.P. 17alpha-ethinyl estradiol affects anxiety and shoaling behavior in adult male zebra fish (Danio rerio). Aquat. Toxicol. 2011, 105, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aris, A.Z.; Shamsuddin, A.S.; Praveena, S.M. Occurrence of 17alpha-ethynylestradiol (EE2) in the environment and effect on exposed biota: A review. Environ. Int. 2014, 69, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirling, M.; Bohlen, A.; Triebskorn, R.; Kohler, H.R. An invertebrate embryo test with the apple snail Marisa cornuarietis to assess effects of potential developmental and endocrine disruptors. Chemosphere 2006, 64, 1730–1738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.L.; Feng, Y.L.; Song, J.L.; Zhou, X.S. Zearalenone: A mycotoxin with different toxic effect in domestic and laboratory animals’ granulosa cells. Front. Genet. 2018, 9, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švarc-Gajić, J.; Brezo-Borjan, T.; Jakšić, S.; Despotović, V.; Finčur, N.; Bognár, S.; Jovanović, D.; Šojić Merkulov, D. Decomposition of organic pollutants in subcritical water under moderate conditions. Processes 2024, 12, 1293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhamorikar, R.S.; Lade, V.G.; Kewalramani, P.V.; Bindwal, A.B. Review on integrated advanced oxidation processes for water and wastewater treatment. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2024, 138, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, S.; Jovanović, D.; Despotović, V.; Jakšić, S.; Panić, S.; Milanović, M.; Finčur, N.; Putnik, P.; Šojić Merkulov, D. Advanced photocatalytic degradation of organic pollutants using green tea-based ZnO nanomaterials under simulated solar iradiation in agri-food wastewater. Foods 2025, 14, 622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical photolysis of water at a semiconductor electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.M.; Lai, C.W.; Ngai, K.S.; Juan, J.C. Recent developments of zinc oxide based photocatalyst in water treatment technology: A review. Water Res. 2016, 88, 428–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parihar, V.; Raja, M.; Paulose, R. A brief review of structural, electrical and electrochemical properties of zinc oxide nanoparticles. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2018, 53, 119–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparelli, R.; Fanizza, E.; Curri, M.L.; Cozzoli, P.D.; Mascolo, G.; Agostiano, A. UV-induced photocatalytic degradation of azo dyes by organic-capped ZnO nanocrystals immobilized onto substrates. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2005, 60, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bognár, S.; Putnik, P.; Šojić Merkulov, D. Sustainable green nanotechnologies for innovative purifications of water: Synthesis of the nanoparticles from renewable sources. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirelkhatim, A.; Mahmud, S.; Seeni, A.; Kaus, N.H.M.; Ann, L.C.; Bakhori, S.K.M.; Hasan, H.; Mohamad, D. Review on zinc oxide nanoparticles: Antibacterial activity and toxicity mechanism. Nano-Micro Lett. 2015, 7, 219–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Pathak, S.; Srivastava, A.K.; Prawer, S.; Tomljenovic-Hanic, S. ZnO nanomaterials: Green synthesis, toxicity evaluation and new insights in biomedical applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 876, 160175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Maksoud, Y.; Imam, E.; Ramadan, A. TiO2 solar photocatalytic reactor systems: Selection of reactor design for scale-up and commercialization—Analytical review. Catalysts 2016, 6, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwer, H.; Mahmood, A.; Lee, J.; Kim, K.-H.; Park, J.-W.; Yip, A.C.K. Photocatalysts for degradation of dyes in industrial effluents: Opportunities and challenges. Nano Res. 2019, 12, 955–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navidpour, A.H.; Xu, B.; Ahmed, M.B.; Zhou, J.L. Immobilization of TiO2 and ZnO by facile surface engineering methods to improve semiconductor performance in photocatalytic wastewater treatment: A review. Mater. Sci. Semicond. 2024, 179, 108518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, D.; Bognár, S.; Despotović, V.; Finčur, N.; Jakšić, S.; Putnik, P.; Deák, C.; Kozma, G.; Kordić, B.; Šojić Merkulov, D. Banana peel extract-derived ZnO nanopowder: Transforming solar water purification for safer agri-food production. Foods 2024, 13, 2643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

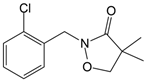

- PubChem: Clomazone. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/54778 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

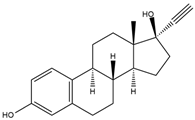

- PubChem: 17α-Ethinylestradiol. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5991 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

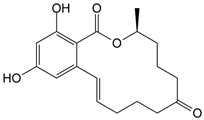

- PubChem: Zearalenone. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/5281576 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

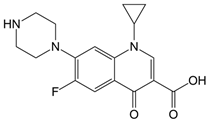

- PubChem: Ciprofloxacin. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/2764 (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- PubChem: Tembotrione. Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Tembotrione (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Xu, C.; Willenbacher, N. How rheological properties affect fine-line screen printing of pastes: A combined rheological and high-speed video imaging study. J. Coat. Technol. Res. 2018, 15, 1401–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauc, J. Optical properties and electronic structure of amorphous Ge and Si. Mater. Res. Bull. 1968, 3, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubelka, P.; Munk, F. An article on optics of paint layers. Z. Techn. Physik. 1931, 12, 593–601. [Google Scholar]

- Köferstein, R.; Jäger, L.; Ebbinghaus, S.G. Magnetic and optical investigations on LaFeO3 powders with different particle sizes and corresponding ceramics. Solid State Ion. 2013, 249–250, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samardžić, N.M.; Bajac, B.; Bajić, J.; Đurđić, E.; Miljević, B.; Srdić, V.V.; Stojanović, G.M. Photoresistive switching of multiferroic thin film memristors. Microelectron. Eng. 2018, 187–188, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miljević, B.; van der Bergh, J.M.; Vučetić, S.; Lazar, D.; Ranogajec, J. Molybdenum doped TiO2 nanocomposite coatings: Visible light driven photocatalytic self-cleaning of mineral substrates. Ceram. Int. 2017, 43, 8214–8221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, D.; Orčić, D.; Šojić Merkulov, D.; Despotović, V.; Finčur, N. Study of factors impacting the light-driven removal of ciprofloxacin (Ciprocinal®) and identification of degradation products using LC–ESI–MS2. J. Photochem. Photobiol. 2025, 460, 116119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šojić Merkulov, D.; Vlazan, P.; Poienar, M.; Bognár, S.; Ianasi, C.; Sfirloaga, P. Sustainable removal of 17α-ethynylestradiol from aqueous environment using rare earth doped lanthanum manganite nanomaterials. Catal. Today 2023, 424, 113746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, A.; Jalil, A.; Ilyas, S.Z.; Iqbal, M.F.; Ali Shah, S.Z.; Baqir, Y. Green-route synthesis and ab-initio studies of a highly efficient nano photocatalyst:Ce/zinc-oxide nanopetals. Heliyon 2024, 10, e25581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharthasaradhi, R.; Nehru, L.C. Structural and phase transition of α-Al2O3powders obtained by co-precipitation method. Ph. Transit. 2015, 89, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Salam, A.I.; Soliman, T.S.; Khalid, A.; Awad, M.M.; Abdallah, S. Effect of reduced graphene oxide on the structural and optical properties of ZnO nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 2024, 355, 135465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, H.; Ikram, M.; Ali, S.; Shahzadi, A.; Aqeel, M.; Haider, A.; Imran, M.; Ali, S. Enhanced drug efficiency of doped ZnO–GO (graphene oxide) nanocomposites, a new gateway in drug delivery systems (DDSs). Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 015405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassegn Weldegebrieal, G.; Kassegn Sibhatu, A. Photocatalytic degradation of organic contaminants in wastewater treatment. In Environmental Microbiology; Shah, M., Ed.; De Gruyter Brill: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 113–136. [Google Scholar]

- Jevtić, I.; Jakšić, S.; Šojić Merkulov, D.; Bognár, S.; Abramović, B.; Ivetić, T. Matrix effects of different water types on the efficiency of fumonisin B1 removal by photolysis and photocatalysis using ternary- and binary-structured ZnO-based nanocrystallites. Catalysts 2023, 13, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajbongshi, B.M. Photocatalyst: Mechanism, challenges, and strategy for organic contaminant degradation. In Handbook of Smart Photocatalytic Materials; Hussain, C.M., Kumar Mishra, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2020; pp. 127–149. [Google Scholar]

- Finčur, N.L.; Grujić-Brojčin, M.; Šćepanović, M.J.; Četojević-Simin, D.D.; Maletić, S.P.; Stojadinović, S.; Abramović, B.F. UV-driven removal of tricyclic antidepressive drug amitriptyline using TiO2 and TiO2/WO3 coatings. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2021, 132, 1193–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topkaya, E.; Konyar, M.; Yatmaz, H.C.; Ozturk, K. Pure ZnO and composite ZnO/TiO2 catalyst plates: A comparative study for the degradation of azo dye, pesticide and antibiotic in aqueous solutions. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2014, 430, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, N.Y.Y.; Chiam, S.L.; Leo, C.P.; Pung, S.Y.; Chang, C.K.; Ang, W.L. Suppression of charge recombination using microfibrillated cellulose in carboxymethyl cellulose coatings containing ZnO nanorods and BiOCl during photoelectrocatalysis. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jovanović, D.; Bognár, S.; Finčur, N.; Despotović, V.; Putnik, P.; Bajac, B.; Jakšić, S.; Miljević, B.; Šojić Merkulov, D. Eco-Friendly ZnO Nanomaterial Coatings for Photocatalytic Degradation of Emerging Organic Pollutants in Water Systems: Characterization and Performance. Nanomaterials 2026, 16, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010023

Jovanović D, Bognár S, Finčur N, Despotović V, Putnik P, Bajac B, Jakšić S, Miljević B, Šojić Merkulov D. Eco-Friendly ZnO Nanomaterial Coatings for Photocatalytic Degradation of Emerging Organic Pollutants in Water Systems: Characterization and Performance. Nanomaterials. 2026; 16(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleJovanović, Dušica, Szabolcs Bognár, Nina Finčur, Vesna Despotović, Predrag Putnik, Branimir Bajac, Sandra Jakšić, Bojan Miljević, and Daniela Šojić Merkulov. 2026. "Eco-Friendly ZnO Nanomaterial Coatings for Photocatalytic Degradation of Emerging Organic Pollutants in Water Systems: Characterization and Performance" Nanomaterials 16, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010023

APA StyleJovanović, D., Bognár, S., Finčur, N., Despotović, V., Putnik, P., Bajac, B., Jakšić, S., Miljević, B., & Šojić Merkulov, D. (2026). Eco-Friendly ZnO Nanomaterial Coatings for Photocatalytic Degradation of Emerging Organic Pollutants in Water Systems: Characterization and Performance. Nanomaterials, 16(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano16010023