3.1. Molecular Assembly and Polymerization Mechanisms

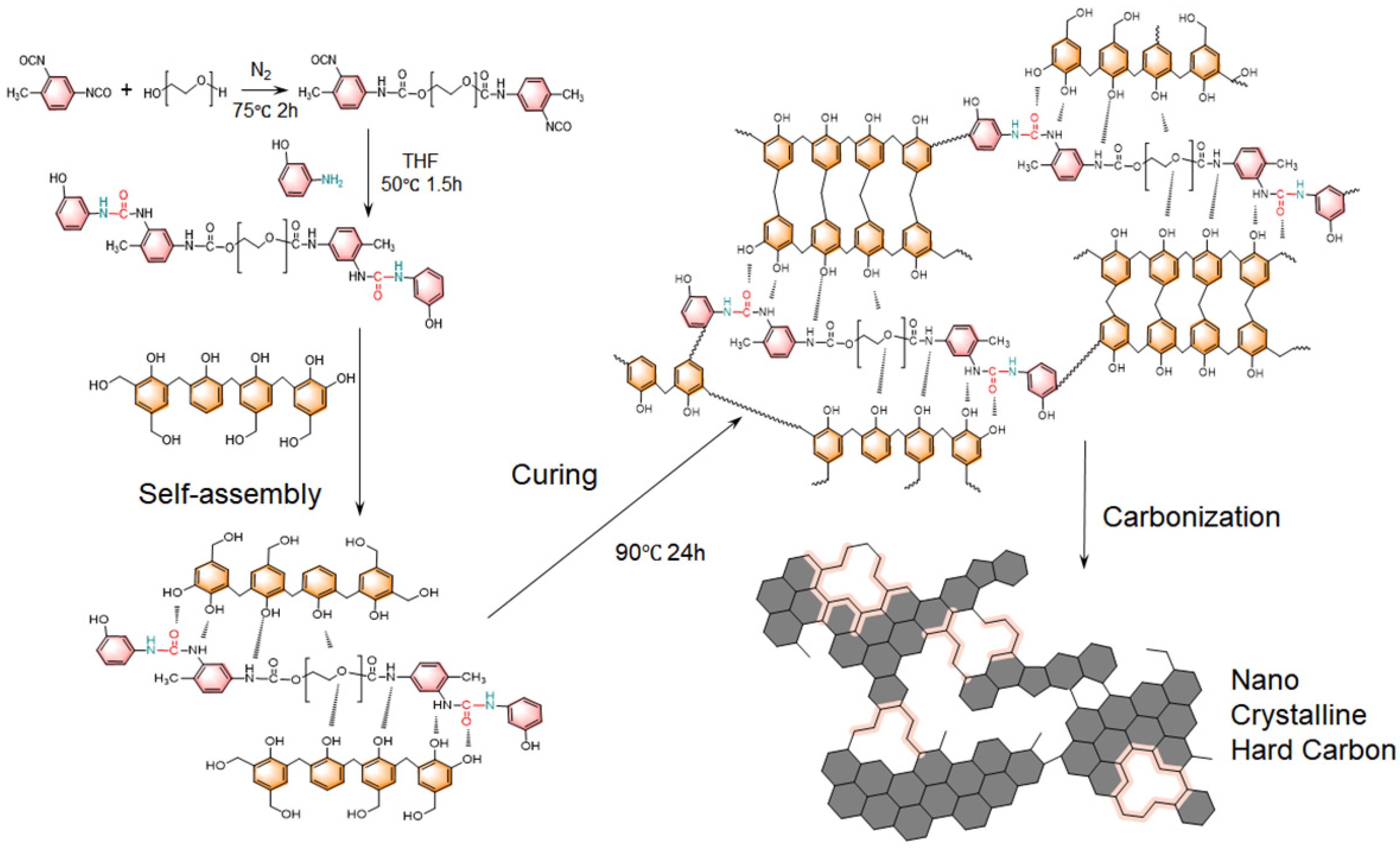

The preparation of CA was illustrated in

Figure 1. First, a polyurethane-urea oligomer (PUU) was synthesized by modifying polyethylene glycol (PEG) with toluene diisocyanate (TDI) and subsequently end-capped with 3-aminophenol. In this step, the hydroxyl-terminated PEG reacts with TDI to form isocyanate-terminated PEG chains, which are then capped by reacting with 3-aminophenol to prevent undesired polymerization from isocyanate. This creates PEG-based molecules bearing urethane (from the PEG–TDI reaction) and urea (from the TDI–3-aminophenol reaction) linkages at both ends. These terminal urea and urethane groups can form strong intra and intermolecular hydrogen bonds, which serve as the primary driving force for the self-assembly of PUU chains in the subsequent Pre CA formation. Next, a carbon precursor alcogel is formed by the co-polymerization of the phenol-formaldehyde (PF) resin with the PUU in solution. The polymerization of the PF resin proceeds mainly via condensation reactions between phenolic rings and hydroxymethyl groups (

Figure S1). Hydroxymethyl-functionalized aromatic rings react with other active aromatic sites with elimination of water, forming methylene bridges that crosslink the growing network. Through this polycondensation, the PUU’s phenolic end-groups become chemically integrated into the PF resin matrix, creating an interpenetrating network. Throughout this process, the hydrogen-bond-driven self-assembly of PUU components helps organize the structure on a molecular level, while the PF crosslinking builds a rigid scaffold around and through the self-assembled PF-PUU. As the PF-PUU polymerization progresses, a reaction-induced phase separation occurs (

Figure 2a). The initially homogeneous solution segregates into a solid polymer-rich phase and a solvent-rich phase. The polymer-rich phase forms an interconnected skeleton of colloidal particle, which acts as the skeleton of the Pre CA gel. This phase separation yields a continuous porous network formed by the agglomeration of the polymer particles, while the separated solvent regions will become pores later. After the polymerization, the wet gel is subjected to ambient-pressure drying, which removes the solvent and preserves the porous structure. Finally, the dried Pre CA is carbonized to yield CA. During carbonization, the organic network is converted into nanocrystalline hard carbon framework, largely retaining the original gel’s structure. The final CA thus consists of a highly porous network of carbon nanoparticles, derived from the PF-PUU polymer network, where the hydrogen-bond-directed self-assembly and in situ PF condensation have produced a uniform, nanoscale structure. This structure combines the benefits of both components, the robust carbon framework and the hierarchical ordering imparted by the self-assembled hydrogen-bonded PUU domains.

As illustrated in

Figure 2a, the preparation route for the carbon aerogel is both facile and energy efficient. The gelation and curing processes proceed at a relatively low temperature of 90 °C, and the entire synthesis avoids time-consuming solvent exchange or supercritical drying. Notably, the Pre CA exhibited negligible shrinkage during ambient pressure drying, highlighting the mechanical robustness and dimensional stability of the pre-carbonized framework. To elucidate the self-assembly behavior, dynamic light scattering (DLS) and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analyses were conducted. FTIR spectra (

Figure 2b) confirm the formation of hydrogen bonding as the characteristic C=O stretching vibration of the PUU component shifts from 1703 cm

−1 to 1734 cm

−1 upon mixing with PF, indicating the participation of the carbonyl group in hydrogen bonding interactions. Self-assembly was further probed by DLS. As shown in

Figure 2c, individual PF and PUU sol solutions displayed hydrodynamic radii (Rh) of approximately 3.0 nm and 2.4 nm, respectively. Upon mixing, the PF and PUU sols in ethanol, a new and significantly larger diffusion mode emerged, corresponding to an Rh of 34 nm, indicating the formation of supramolecular aggregates. This result provides direct evidence for hydrogen-bonding-driven assembly between PF and PUU components. The spontaneous assembly is attributed to the strong hydrogen bond donors present in the PUU chains (urea and urethane groups) and the multiple hydroxyl and phenolic groups in PF, which act as complementary acceptors and donors. These findings collectively confirm that the intermolecular hydrogen bonding between PF and PUU is the dominant driving force for the formation of a well-organized precursor network. The density of obtained Pre CAs is 0.35–0.38 g/cm

3, and the corresponding CAs showed density between 0.56 and 0.63 g/cm

3, varied with different carbonization temperature. The picture of CA was shown in

Figure 2e, the carbon aerogel remained a cylinder shape without any crack. This approach offers a simple, scalable, and energy-efficient route for fabricating high-performance carbon aerogels without the need for complex drying processes or structural templates.

3.2. Morphology Analysis of Carbon Aerogels

The morphology evolution of Pre CA and their corresponding CA as a function of PUU content is presented in

Figure 3a,b. With increasing PUU loading (5%, 10%, 20%, and 30%), the precursor gel network exhibited dramatic changes in particle size and interconnection patterns. Specifically, CAs showed similar structure evolution as they inherit similar particles’ packing structure from Pre CAs. SEM images and the corresponding size distribution histograms show that the average particle size of CAs increased substantially from 109 nm (5% PUU) to 192 nm (10%), 415 nm (20%), and up to 1516 nm (30%). This clear size amplification suggests that the amount of PUU significantly influences the colloidal aggregation dynamics during gelation, due to its role in mediating hydrogen-bonding-driven self-assembly and modulating the phase separation behavior of the sol system.

As shown in

Figure 3b, the skeleton structure became bulky and continuous with PUU addition. At low PUU content (5%), the particles are small and loosely packed, forming a “pearl-necklace”-type framework with weak interparticle contacts. As PUU content rises, the interparticle “necks” become thicker and more fused, giving rise to a dense, integrated packing structure with stronger interparticle bridging. At 30% PUU, the particles coalesce into smooth, large granular domains with significantly reduced surface roughness and fewer visible pore boundaries, indicative of a transition from nanoscale to microscale structural units. This morphological shift reflects an enhanced phase separation degree at higher PUU concentrations, resulting in less nano level porosity. The corresponding carbon aerogels retained these microstructural differences after pyrolysis, further confirming the structural inheritance from precursor to carbonized state. These observations collectively demonstrate that PUU content serves as a molecular-level regulator, enabling precise control over particle size, skeleton connectivity, and packing morphology within the aerogel network. The ability to tune the skeletal morphology through PUU content, without the need for external templating or complex drying techniques, demonstrates the effectiveness of this molecular assembly strategy in directing nanoscale structure and ensuring its mechanical performance.

3.3. Influence of Pyrolysis Temperature on Graphitization and Mechanical Properties

Pyrolysis temperature has a significant impact on the structural ordering and graphitization degree of CAs. As shown in

Figure 4, both Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction (XRD) analyses reveal progressive structural evolution with increasing carbonization temperature from 800 °C to 1600 °C. XRD patterns (

Figure 4a) display the characteristic (002) diffraction peak of turbostratic carbon, and the corresponding interlayer spacing d

002 gradually decreases with increasing temperature. Specifically, d

002 values change from 0.384 nm at 1200 °C to 0.374 nm at 1600 °C, approaching but still above the ideal graphite value of 0.335–0.340 nm (

Figure 4b). At 800 °C, the (002) peak remains broad and centered around 22.48°, indicative of a poorly ordered hard carbon structure. The relatively small shift in d-spacing suggests that although some rearrangement and partial stacking of graphene layers occur at higher temperatures, the overall graphitic ordering remains limited, consistent with the typical behavior of carbon derived from phenolic resin precursors.

Raman spectra (

Figure 4c) show a more pronounced carbon crystalline evolution. The intensity ratio of the disorder-induced D-band (~1350 cm

−1) to the graphitic G-band (~1580 cm

−1), denoted as I

D/I

G, decreases significantly from 2.55 at 800 °C to 1.85 at 1600 °C (

Figure 4d). This decline indicates a substantial reduction in defect density and a corresponding increase in graphitic domain size. While the XRD data suggests moderate ordering at the nanocrystalline scale, the Raman data reflect local bonding environment improvements and a reduction in amorphous carbon content with increasing pyrolysis temperature. Taken together, these results demonstrate that although phenolic resin-based carbon aerogels typically form hard carbon structures with limited graphitic stacking, thermal treatment above 1200 °C can significantly improve the in-plane ordering, as reflected in Raman results. The incorporation of PUU not only modulates the precursor’s microstructure but also enhances the degree of structural ordering upon carbonization, offering a feasible route to engineer nanocrystalline carbon frameworks with improved mechanical performance.

To further investigate the structural evolution of the carbon aerogels during pyrolysis, high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) was conducted on samples treated at 1200 °C, 1400 °C, and 1600 °C (

Figure 5). The results reveal transformation from turbostatic carbon to nanocrystalline domains, consistent with the Raman and XRD observations. At 1200 °C, the carbon structure remains largely disordered, with randomly oriented and curved graphene layers visible throughout the matrix. No significant lattice alignment or long-range order is observed, confirming that the material still predominantly retains turbostatic hard carbon features. This supports the Raman data showing a relatively high I

D/I

G ratio (2.31) and the broad (002) peak in XRD centered around d

002 = 0.384 nm. In contrast, at 1400 °C, distinct graphitic nanocrystals begin to emerge. These domains, typically ranging from 2 to 3 nm in lateral size, are highlighted in the image and exhibit partially aligned edges with local stacking. This is related to the particle-packing structure formed by PUU and PF through thick interparticle necks, leading to denser molecular packing and the creation of robust, thick interparticle necks. This reduces structural defects and enhances load-bearing continuity. Such nanocrystalline features represent emerging ordering within the carbon matrix, as graphene sheets begin to coalesce into localized crystalline regions. The corresponding Raman I

D/I

G = 2.13 further confirms the partial graphitization at this stage. Upon increasing the carbonization temperature to 1600 °C, the carbon aerogel exhibits a significantly enhanced degree of ordering. HRTEM images reveal extended graphitic region, spanning over 10 nm in length, with more continuous stacking and reduced curvature. These interconnected nanocrystalline domains indicate the development of a quasi-graphitic framework, approaching the onset of long-range order. The accompanying reduction in I

D/I

G and narrowing of the XRD (002) peak further corroborate this structural transformation. Selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns also support this trend. While the 1200 °C sample displays diffuse rings characteristic of amorphous carbon, the 1400 °C and especially 1600 °C samples exhibit sharper diffraction rings, indicating improved crystallinity and increased domain size. These findings highlight that although phenolic-resin-derived aerogels tend to form hard carbon, the molecularly guided self-assembled network and elevated local density introduced by the PUU component facilitate nanocrystal formation at relatively lower temperatures of 1400 °C. The ability to tune and stabilize these structural units offers a pathway to engineer mechanically robust, thermally resilient carbon aerogels with hybrid amorphous/graphitic characteristics.

The compressive mechanical properties of the carbon aerogels exhibit a strong dependence on pyrolysis temperature, reflecting the evolving carbon microstructure and interconnectivity of the particle skeleton. As shown in

Figure 6, both modulus and strength respond nonlinearly to increasing temperature, while elongation at break reflects the material’s ductility and failure mode. At 800 °C, the carbon aerogel presents a relatively low modulus of 1489.56 MPa, but surprisingly, a moderate compressive strength of 46.84 MPa and the highest elongation at break (5.11%). This behavior suggests a highly disordered yet compliant amorphous framework that can deform to some extent before failure. The loose packing and disorder nature of the carbon, as confirmed by XRD and Raman, allow strain redistribution under load. At 1000 °C, the modulus slightly increases to 1525.11 MPa, but the strength drops to 31.12 MPa, and the elongation at break sharply decreases to 3.12%. After heat treatment at 1000 °C, the carbon skeleton begins to undergo partial densification, but the degree of carbon ordering is still insufficient, as reflected by the relatively high I

D/I

G ratio in Raman spectra compared with higher-temperature samples. This intermediate state leads to inhomogeneous local graphitization and defect distribution, which weakens the structural integrity and makes the network more brittle and defect-prone, explaining the observed decrease in compressive strength relative to the 800 °C sample. A similar pattern is observed at 1200 °C, where although the modulus increases substantially to 2492.45 MPa, the strength only recovers to 60.47 MPa, and elongation remains low (3.13%). These samples exhibit higher stiffness but poor toughness.

CA-10%-1400 °C yields the best overall mechanical performance, with a modulus of 2934.59 MPa, a compressive strength of 110 MPa, and a moderate elongation of 4.21%. This balance of stiffness and ductility arises from the emergence of uniformly dispersed 2~3 nm graphitic nanocrystallines, which reinforce the amorphous matrix and enable enhanced stress transfer across the skeleton. The thickened particle necks formed during self-assembly remain intact after carbonization, further promoting load-bearing continuity. This hybrid nanostructure, consisting of rigid crystalline domains and an interconnected amorphous framework, provides both modulus enhancement and energy dissipation capacity, leading to exceptional mechanical synergy. Interestingly, at 1600 °C, although the modulus remains relatively high (2571.53 MPa), the strength decreases to 78.48 MPa, and elongation further drops to 3.84%. This decline is attributed to over-graphitization and crystallite coarsening, which induce localized stress concentration. The excessive rigidity of the highly graphitized skeleton reduces its ability to accommodate strain, resulting in reduced toughness and premature failure under compression.

Taking mechanical properties and characterization results together, it can be concluded that increasing temperature improves stiffness through enhanced carbon ordering, but only a moderate degree of nanocrystallization (1400 °C) yields optimal strength and ductility. This underscores the critical role of nanoscale crystalline reinforcement embedded within a well-connected network in achieving high-performance carbon aerogels. Excessive graphitization, while beneficial to thermal stability, can be detrimental to mechanical resilience. The graphitized nanocrystals formed during pyrolysis provided additional strength by enhancing interlayer stress transfer, while the neck structure of the particle packing ensured continuous load-bearing paths.

3.4. Effect of Closed-Cell Structure on Thermal Insulation Performance

The pyrolysis temperature significantly modulates the hierarchical structure of the carbon aerogels, thereby governing their thermal insulation properties. As shown in

Figure 7a, the thermal conductivity increased markedly from 0.14 W·m

−1·K

−1 for CA-10%-800 to 0.21 W·m

−1·K

−1 for CA-10%-1000, and further to 0.32 W·m

−1·K

−1 for CA-10%-1200. Between 1200 °C and 1400 °C, the value remained relatively stable (0.30 W·m

−1·K

−1), while a significant jump to 0.52 W·m

−1·K

−1 occurred for CA-10%-1600. This trend is closely correlated with the evolution of closed pore size and skeleton characteristics. As shown in

Figure 7c, SAXS curves exhibited a steep intensity drop in the low-q region and a pronounced shoulder at q range of 0.04–0.35 Å

−1, evidencing a substantial population of nanometer-scale closed pores appeared. With increasing temperature, the shoulder peaks showed enhanced relative intensity and gradually shift to lower

q, indicating pore volume and characteristic length of the porous network increased synergistically. To quantify structural differences among the CAs with different temperature, the curves were fitted with a Debye-type model [

32],

where

A accounts for Porod scattering from the external surface,

describes the density–density correlation of the internal structure,

is the correlation length, and

is the incoherent background. The radius of gyration of the nanopores,

, defined as the root-mean-square distance from the center of mass, is related to

(Debye–Anderson–Brumberger form) by

. According to SAXS results (

Figure 7d), the closed pore radius increased from 0.38 nm at 800 °C to 0.62 nm at 1400 °C, and slightly to 0.64 nm at 1600 °C, suggesting a gradual pore coarsening with temperature. For thermal transportation within the carbon aerogel backbone, the pore structure can be considered as defects for the heat transfer route. The higher the porosity, the more frequent the scattering of phonons at the pore interfaces, and the lower the thermal conductivity. Furthermore, micropores are also structures formed during the carbonization process. Micropores are more abundant in the temperature range of 800–1000 °C and gradually decrease as the temperature rises to 1200–1600 °C due to structural rearrangement and partial pore coalescence, while it generally has a negligible effect on thermal insulation [

32,

33].

The open pore structure also played a vital role for thermal insulation. Mercury Intrusion porosimetry was employed to analyze the open pore architecture and skeleton density of carbon aerogels subjected to various pyrolysis temperatures. As illustrated in

Figure 7e, the pore size distribution revealed a relatively narrow peak in the meso–macroporous range (20–50 nm) across all samples. The nano open pores can suppress gas convection through the Knudsen effect, where gas molecules collide more frequently with the pore walls than with each other, effectively reducing the convective heat transfer. With increasing pyrolysis temperature, the mean pore diameter varied between 32 nm and 50 nm. This evolution suggests volume shrinkage during thermal treatment, accompanied by partial open pore collapse. Concurrently, the skeleton density increased from 1.25 g/cm

3 to 1.43 g/cm

3, indicating gradual densification and increased carbon framework connectivity through graphitization and loss of volatile components. At lower temperatures (800–1000 °C), the rise in thermal conductivity is primarily attributed to the beginning of graphitization and initial densification. From 1000 to 1400 °C, despite continued growth in closed pores and marginal increase in skeletal density, the conductivity plateaued. This plateau can be explained by the balance between enhanced phonon transport from structural ordering and phonon scattering due to residual turbostratic domains and pore interfaces. At 1600 °C, the thermal conductivity increased sharply. This can be ascribed to the formation of more continuous nanocrystalline graphite domains, which promote long-range phonon transport. Additionally, the enlarged closed pores and increased skeleton density reduce interfacial thermal resistance, further boosting heat conduction.

Taken together, the results reveal that thermal conductivity is governed by a synergistic interplay of closed pore structure, skeleton structure, and graphitic continuity. Moderate graphitization offers a balance between insulation and stability, while extensive ordering and densification at 1600 °C shift the material toward higher conductivity, potentially suitable for heat-spreading rather than insulating applications.