Organic Matter Enrichment and Reservoir Nanopore Characteristics of Marine Shales: A Case Study of the Permian Shales in the Kaijiang–Liangping Trough

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Regional Geological Setting

3. Experimental Methods

4. Results

4.1. Petrographic Description

4.2. Organic Geochemistry

4.3. Inorganic Geochemistry

4.4. Microscopic Reservoir Experimental Data

4.4.1. Physical Properties

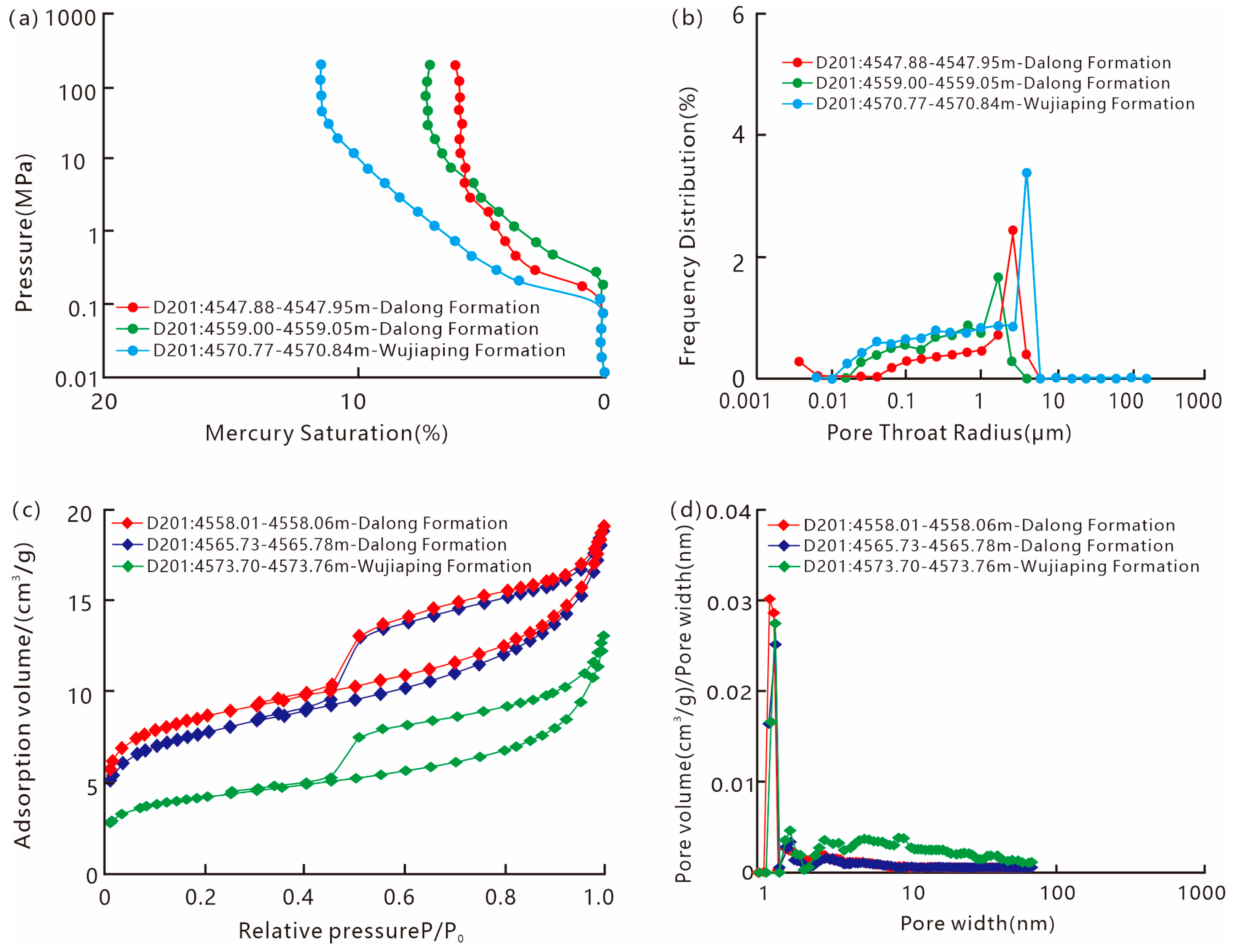

4.4.2. Pore Types and Structures

5. Discussion

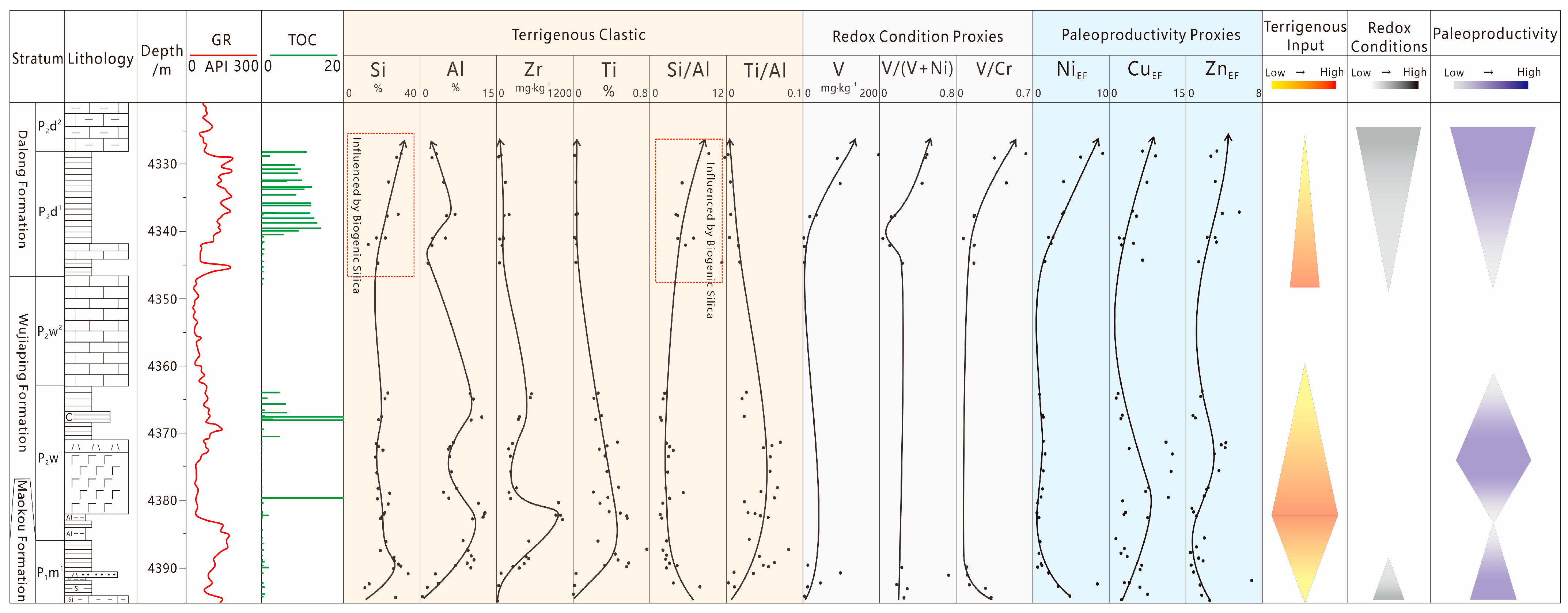

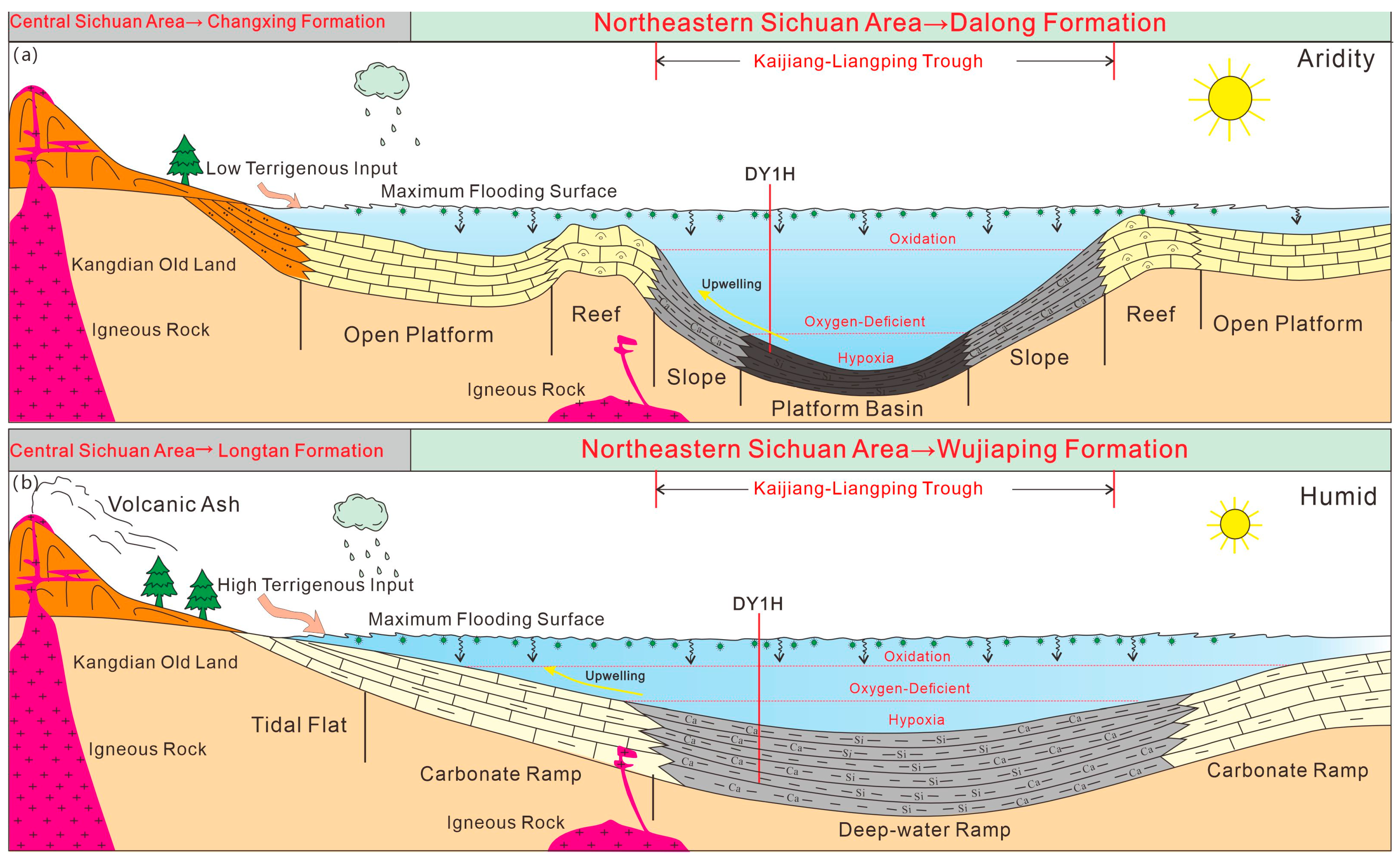

5.1. Mechanism and Pattern of Differential Enrichment of Organic Matter

5.1.1. Paleoclimate

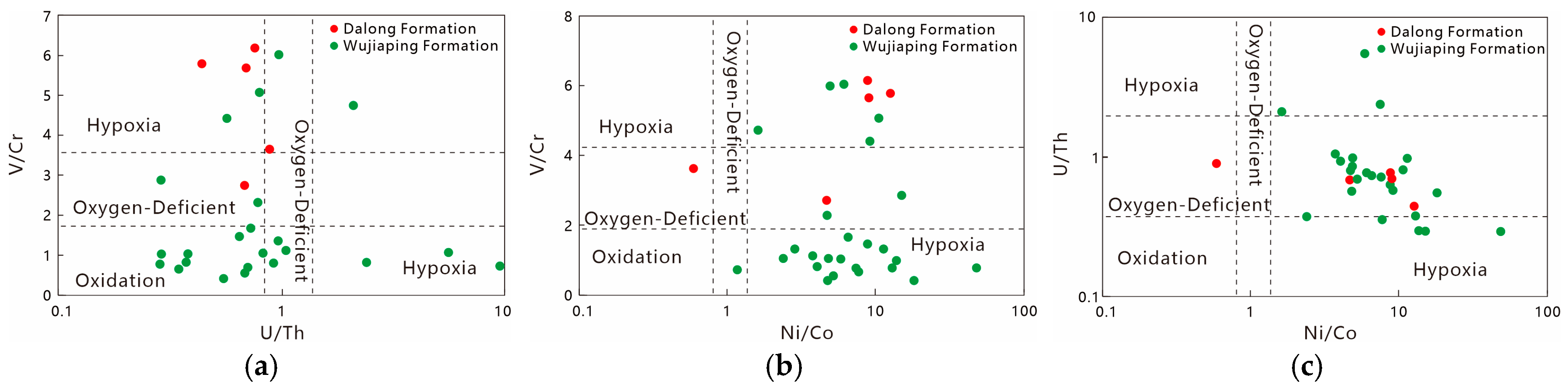

5.1.2. Redox Conditions

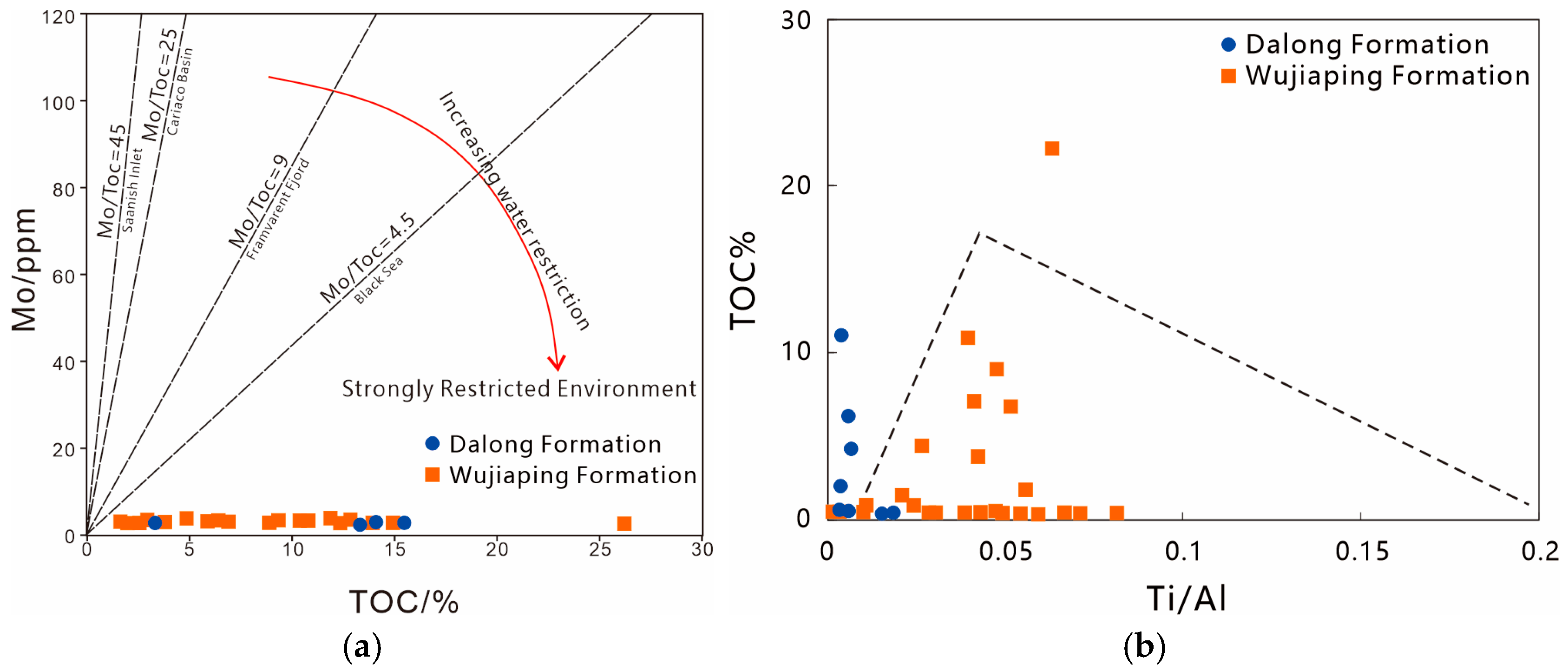

5.1.3. The Degree of Water Body Limitation and Terrestrial Input

5.1.4. Paleoproductivity

5.1.5. Pattern of Differential Enrichment of Organic Matter

5.2. Reservoir Differential Characteristics

5.3. The Significance of Shale Gas Exploration

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The Wujiaping Formation in the Kaijiang–Liangping Trough area was deposited in a carbonate ramp setting. With the intensification of rifting, the Dalong Formation transitioned to a rimmed-platform sedimentary model, thereby governing the distribution of Permian shales, the patterns of organic matter enrichment, and the differential characteristics of reservoirs.

- (2)

- During the Late Permian, the climate gradually transitioned from semi-arid and semi-humid to arid. Along with this transition, terrigenous input weakened, weathering gradually diminished, while reducibility, water restriction degree, and paleoproductivity gradually increased.

- (3)

- In the study area, the Dalong Formation shale exhibits higher brittle mineral content, higher organic matter abundance, and more developed reservoir nanopores. It serves as a more favorable target horizon for subsequent shale gas exploration and development.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lin, Y.L.; Wang, W.Y. Another Major Shale Gas Field Comes into Being. China Petroleum and Chemical Industry News. Available online: http://newapp.sinopecnews.com.cn/shihua/template/displayTemplate/news/newsDetail/100001/7135761.html (accessed on 21 August 2025).

- Jin, Z.; Liu, G.; Wang, P.; Nie, H.; Li, M.; Wang, G. Exploration potential and targets of the Permian shale gas in the Yangtze region, South China. Oil Gas Geol. 2025, 46, 335–347. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, R.; Yang, H.; Wu, W.; Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Huang, H. Controlling factors and exploration potential of shale gas enrichment and high yield in the Permian Dalong Formation, Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 253–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Tian, H.; Wang, Q.; Song, F.; Zhang, S.; Chen, Y. Characteristics and formation mechanism of Permian marine shale of Kaijiang-Liangping trough in northern Sichuan Basin. Lithol. Reserv. 2025, 37, 108–119. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Wang, L.; Shi, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Pu, F.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Xu, H. Characteristics and potential for exploration of shale reservoir inDalong Formation in northern Sichuan. J. Chengdu Univ. Technol. (Sci. Technol. Ed.) 2024, 51, 361–378. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Y. Controlling Factors of Source Rock Development and Distribution in the Middle-Upper Permian, Northeastern Sichuan Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Petroleum (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, Y.; Bao, H.; Zhu, H.; Lu, Y.; Meng, Z.; Li, K.; Chen, F. Radiolarian assemblage from the Upper Permian Wujiaping Formationin the eastern Sichuan Basin and its hydrocarbon source significance. Bull. Geol. Sci. Technol. 2024, 43, 167–180. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, B.; Wen, H.; Liao, Y.; Zhang, B.; Yao, Y.; Wen, S.; Yang, K. Shale reservoirs characteristics and favorable areas distribution of the second member of Permian Wujiaping Formation in northeastern Sichuan Basin. Lithol. Reserv. 2025, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Ma, W.; Yang, X.; Li, R.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wu, Q.; He, L. Diagenesis and its influence on pore development of deep shale reservoirs in northeastern Sichuan Basin: A case study of Wujiaping Formation and Dalong Formation in Well DY1H. Mar. Orig. Pet. Geol. 2024, 29, 385–400. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, Y.; Sun, H.F.; Ye, Y.H.; Wang, J.X.; Song, J.M.; Wang, X.F.; Qiu, Y.C.; Chen, W.; Dai, X. Geological conditions and exploration potential of shale gas in northeastern Sichuan Basin: A case study of Upper Permian Wujiaping Formation in Well Fengtan 1. Nat. Gas Explor. Dev. 2023, 46, 133–147. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, P.; Wu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wu, W.; Zhang, R.; Wu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; et al. Enrichment conditions and favorable areas for exploration and development of marine shale gas in Sichuan Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2023, 44, 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Hu, D.; Lu, Y.; Liu, R.; Liu, X. Advantageous shale lithofacies of Wufeng Formation-Longmaxi Formation in Fuling gas field of Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2016, 43, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 14505-1993; Method for Chemical Analysis of Rocks and Ores. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 1993. Available online: https://std.samr.gov.cn/gb/search/gbDetailed?id=71F772D7D5F2D3A7E05397BE0A0AB82A (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- GB/T 34533-2023; Specification for Scanning Electron Microscope Analysis of Shale. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2023. Available online: https://std.samr.gov.cn/gb/search/gbDetailed?id=FC816D05003E62EBE05397BE0A0AD5FA (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- GA/T 2079-2023; Method for Determination of Trace Elements in Rocks. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2023. Available online: https://std.samr.gov.cn/hb/search/stdHBDetailed?id=10DA874FA31C5DB7E06397BE0A0AB036 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- NB/T 14008-2015; Method for High Pressure Mercury Injection Test of Rocks. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2015. Available online: https://std.samr.gov.cn/hb/search/stdHBDetailed?id=F286ADBD2ECD7DBDE05397BE0A0AD302 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- DZ/T 0455-2023; Specifications for Nitrogen Adsorption Method for Measurement of Rock Specific Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution. Standardization Administration of China: Beijing, China, 2023. Available online: https://std.samr.gov.cn/hb/search/stdHBDetailed?id=1B9F71E1DE0F9341E06397BE0A0A08E7 (accessed on 17 November 2025).

- Li, T.; Zhu, G.; Zhao, K.; Wang, P. Geological, geochemical characteristics and organic matter enrichment of the black rock series in Datangpo Formation in Nanhua System, South China. Acta Pet. Sin. 2021, 42, 1142–1162. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, L. Organic Matter Enrichment Mechanism and Development Model of Source Rocks in the 2nd Member of Liushagang Formation in Beibuwan Basin. Ph.D. Thesis, China University of Petroleum (Beijing), Beijing, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Algeo, T.J.; Li, C. Redox classification and calibration of redox thresholds in sedimentary systems. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2020, 287, 8–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Guo, J.; Wang, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Jiao, P.; Chen, G. Geochemical characteristics and organic matter enrichment mechanism of the Lower Cambrian Niutitang formation black rock series in central Hunan. J. Cent. South Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2020, 51, 2049–2060. [Google Scholar]

- Algeo, T.J.; Ienall, E. Sedimentary Corg:P ratios, paleocean ventilation, and Phanerozoic atmospheric pO2. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007, 256, 130–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algeo, T.J.; Tribovillard, N. Environmental analysis of paleoceanographic systems based on molybdenum-uranium covariation. Chem. Geol. 2009, 268, 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tribovillard, N.; Algeo, T.; Baudin, F.; Riboulleau, A. Analysis of marine environmental conditions based on molybdenum-uranium covariation–Applications to Mesozoic paleoceanography. Chem. Geol. 2012, 324–325, 46–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paytan, A.; Griffith, E.M. Marine barite: Recorder of variations in ocean export productivity. Deep-Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2007, 54, 687–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Zhou, X.; Wang, G.; Yang, F.; Liu, Y. Factors Affecting Organic Matter Abundance of Marine Source Rocks. Mar. Orig. Pet. Geol. 2009, 14, 20–23. [Google Scholar]

- Twining, B.S.; Baines, S.B.; Bozard, J.B.; Vogt, S.; Walker, E.A.; Nelson, D.M. Metal quotas of plankton in the equatorial Pacific Ocean. Deep-Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2011, 58, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Tian, H.; Yang, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, Q.; Zhu, S.; Jiang, Z. Genetic mechanism of siliceous minerals in Permian marine shales in Northeast Sichuan. J. Shandong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci.) 2024, 43, 35–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, D.; Li, X.; Du, W.; Liu, H.; Li, P.; Wang, R. Control of organic matter enrichment on organic pore development in the Permian marine organic-rich shale, eastern Sichuan Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2023, 44, 379–392. [Google Scholar]

| Serial Number | Well Number | Well Depth | Formation | Quartz (%) | Plagioclase (%) | Calcite (%) | Dolomite (%) | Pyrite (%) | Siderite (%) | Clay (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DY-1H | 4328.21 | P2d1 | 57.7 | 9.1 | 10 | 4.7 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 13.4 |

| 2 | DY-1H | 4328.80 | P2d1 | 20.1 | 14.2 | 2.3 | 0.0 | 6.9 | 0.0 | 52 |

| 3 | DY-1H | 4332.50 | P2d1 | 45.7 | 3.6 | 20 | 15.3 | 6.2 | 0.0 | 9.3 |

| 4 | DY-1H | 4337.20 | P2d1 | 32.7 | 4 | 45 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.2 |

| 5 | DY-1H | 4337.45 | P2d1 | 9.3 | 4.1 | 13.8 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 67.3 |

| 6 | DY-1H | 4340.75 | P2d1 | 32.7 | 2.9 | 49.6 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 10 |

| 7 | DY-1H | 4340.78 | P2d1 | 32.7 | 2.9 | 49.6 | 3.6 | 1.2 | 0.0 | 10 |

| 8 | DY-1H | 4341.80 | P2d1 | 9.3 | 3.8 | 84.5 | 1.4 | 1 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 9 | DY-1H | 4344.40 | P2d1 | 11.3 | 1 | 66 | 21.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 10 | DY-1H | 4363.85 | P2w2 | 54.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 8.2 | 15.3 | 22.5 |

| 11 | DY-1H | 4364.70 | P2w2 | 25.6 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 17.2 | 2.8 | 5.8 | 44 |

| 12 | DY-1H | 4367.30 | P2w2 | 16.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.4 | 21.6 | 57.9 |

| 13 | DY-1H | 4367.79 | P2w2 | 10.6 | 25.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 64 |

| 14 | DY-1H | 4371.23 | P2w2 | 8.9 | 0.0 | 4.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3 | 78.3 |

| 15 | DY-1H | 4371.76 | P2w2 | 14.6 | 13.4 | 55.2 | 2.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 14.6 |

| 16 | DY-1H | 4372.27 | P2w2 | 39.3 | 22.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 38.1 |

| 17 | DY-1H | 4373.22 | P2w1 | 15.3 | 35.8 | 32.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 16.5 |

| 18 | DY-1H | 4375.56 | P2w1 | 10 | 37.9 | 30.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 21.6 |

| 19 | DY-1H | 4377.94 | P2w1 | 34.4 | 5 | 39.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 21.2 |

| 20 | DY-1H | 4378.60 | P2w1 | 25.1 | 0.0 | 3.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 71.7 |

| 21 | DY-1H | 4379.46 | P2w1 | 85.8 | 1.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 | 10.4 |

| 22 | DY-1H | 4380.24 | P2w1 | 9.4 | 50.6 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 37.4 |

| 23 | DY-1H | 4381.54 | P2w1 | 19 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 81 |

| 24 | DY-1H | 4381.80 | P2w1 | 56.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 43.2 |

| 25 | DY-1H | 4382.22 | P2w1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 77.2 |

| 26 | DY-1H | 4382.45 | P2w1 | 7.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 92.4 |

| 27 | DY-1H | 4385.77 | P2w1 | 75.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 24.7 |

| 28 | DY-1H | 4387.18 | P2w1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 100 |

| 29 | DY-1H | 4388.01 | P2w1 | 17.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 82.5 |

| 30 | DY-1H | 4388.65 | P2w1 | 25.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 74.7 |

| 31 | DY-1H | 4389.12 | P2w1 | 51.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 13.5 | 0.0 | 35.1 |

| 32 | DY-1H | 4389.47 | P2w1 | 35.9 | 21 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 7.5 | 0.0 | 35.7 |

| 33 | DY-1H | 4389.75 | P2w1 | 19.8 | 14.9 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 60.7 |

| 34 | DY-1H | 4390.62 | P2w1 | 65.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.1 | 0.0 | 31.6 |

| 35 | DY-1H | 4392.04 | P2w1 | 86.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.9 | 0.0 | 11.6 |

| 36 | DY-1H | 4392.61 | P2w1 | 63.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 27.7 |

| 37 | DY-1H | 4394.00 | P2w1 | 94.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 38 | DY-1H | 4395.15 | P2w1 | 62.8 | 0.0 | 36.5 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| Formation | TOC (%) | Ro (%) | S1 + S2 (mg/g) | Tmax (°C) | δ13Corg | Types of Organic Matter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dalong Formation | 0.17~10.98/2.79 | 1.67~2.42/2.14 | 0.01~0.68/0.16 | 317~597/543 | −28.7~−22.7/−25.9 | Ⅰ |

| Wujiaping Formation | 0.05~22.28/1.32 | 1.95~3.18/2.75 | 0.01~0.87/0.07 | 449~562/514 | −27.6~−21.1/−23.9 | Ⅱ2 |

| Serial Number | Well Number | Well Depth | Formation | Fe2O3 (%) | Mn (%) | Ti (%) | CaO (%) | K2O (%) | S (%) | P (%) | SiO2 (%) | Al2O3 (%) | MgO (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DY-1H | 4328.21 | P2d1 | 2.494 | 0.009 | 0.013 | 7.150 | 1.328 | 0.133 | 0.008 | 64.598 | 6.120 | 0.128 |

| 2 | DY-1H | 4328.80 | P2d1 | 2.096 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 12.405 | 0.919 | 0.087 | 0.016 | 59.619 | 4.433 | 0.063 |

| 3 | DY-1H | 4332.50 | P2d1 | 4.554 | 0.026 | 0.029 | 13.916 | 2.084 | 0.256 | 0.007 | 50.670 | 8.745 | 0.118 |

| 4 | DY-1H | 4337.20 | P2d1 | 3.936 | 0.099 | 0.046 | 1.687 | 2.941 | 0.117 | 0.006 | 61.374 | 13.033 | 0.154 |

| 5 | DY-1H | 4337.45 | P2d1 | 2.984 | 0.714 | 0.031 | 14.959 | 2.184 | 0.090 | 0.013 | 49.178 | 9.873 | 0.255 |

| 6 | DY-1H | 4340.75 | P2d1 | 3.272 | 0.131 | 0.031 | 17.283 | 2.123 | 0.039 | 0.019 | 46.843 | 9.436 | 0.255 |

| 7 | DY-1H | 4340.78 | P2d1 | 2.899 | 0.301 | 0.009 | 23.855 | 1.031 | 0.025 | 0.012 | 36.799 | 4.700 | 1.611 |

| 8 | DY-1H | 4341.80 | P2d1 | 3.027 | 0.128 | 0.038 | 41.826 | 0.673 | 0.012 | 0.012 | 27.660 | 4.329 | 0.127 |

| 9 | DY-1H | 4344.40 | P2d1 | 0.900 | 0.063 | 0.029 | 32.835 | 0.494 | 0.014 | 0.014 | 38.470 | 2.983 | 0.219 |

| 10 | DY-1H | 4363.85 | P2w2 | 10.298 | 0.156 | 0.261 | 3.356 | 2.698 | 0.085 | 0.033 | 49.689 | 18.546 | 0.339 |

| 11 | DY-1H | 4364.70 | P2w2 | 11.836 | 0.167 | 0.216 | 2.062 | 2.867 | 0.286 | 0.011 | 46.546 | 19.726 | 0.279 |

| 12 | DY-1H | 4367.30 | P2w2 | 14.406 | 0.082 | 0.295 | 6.021 | 2.274 | 0.122 | 0.011 | 42.717 | 22.839 | 0.172 |

| 13 | DY-1H | 4367.79 | P2w2 | 28.364 | 0.261 | 0.237 | 1.016 | 1.861 | 0.058 | 0.013 | 39.402 | 18.891 | 0.480 |

| 14 | DY-1H | 4371.23 | P2w2 | 17.189 | 0.099 | 0.462 | 5.039 | 0.070 | 0.006 | 0.024 | 36.707 | 12.263 | 1.242 |

| 15 | DY-1H | 4371.76 | P2w2 | 15.850 | 0.105 | 0.353 | 5.763 | 0.131 | 0.010 | 0.021 | 39.219 | 11.059 | 0.953 |

| 16 | DY-1H | 4372.27 | P2w2 | 15.485 | 0.089 | 0.273 | 6.054 | 0.342 | 0.012 | 0.019 | 44.111 | 10.478 | 0.916 |

| 17 | DY-1H | 4373.22 | P2w1 | 18.214 | 0.124 | 0.334 | 7.769 | 0.081 | 0.007 | 0.021 | 36.217 | 10.899 | 1.438 |

| 18 | DY-1H | 4375.56 | P2w1 | 17.343 | 0.162 | 0.354 | 6.893 | 0.121 | 0.008 | 0.021 | 37.426 | 11.628 | 1.350 |

| 19 | DY-1H | 4377.94 | P2w1 | 22.416 | 0.039 | 0.476 | 1.164 | 0.285 | 0.016 | 0.007 | 38.565 | 13.465 | 1.414 |

| 20 | DY-1H | 4378.60 | P2w1 | 12.733 | 0.026 | 0.212 | 1.587 | 0.270 | 0.005 | 0.016 | 51.853 | 8.707 | 0.878 |

| 21 | DY-1H | 4379.46 | P2w1 | 15.272 | 0.161 | 0.361 | 10.071 | 0.099 | 0.006 | 0.019 | 38.147 | 10.708 | 0.904 |

| 22 | DY-1H | 4380.24 | P2w1 | 7.864 | 0.060 | 0.279 | 1.860 | 2.863 | 0.016 | 0.006 | 49.931 | 21.652 | 0.289 |

| 23 | DY-1H | 4381.54 | P2w1 | 16.195 | 0.089 | 0.375 | 0.316 | 3.307 | 0.006 | 0.005 | 46.205 | 24.080 | 0.255 |

| 24 | DY-1H | 4381.80 | P2w1 | 10.644 | 0.018 | 0.491 | 1.520 | 3.088 | 0.005 | 0.006 | 44.736 | 23.826 | 0.176 |

| 25 | DY-1H | 4382.22 | P2w1 | 14.714 | 0.023 | 0.559 | 0.388 | 2.782 | 0.007 | 0.007 | 42.796 | 23.441 | 0.252 |

| 26 | DY-1H | 4382.45 | P2w1 | 20.073 | 0.041 | 0.564 | 1.330 | 2.147 | 0.007 | 0.008 | 41.449 | 19.454 | 0.370 |

| 27 | DY-1H | 4385.77 | P2w1 | 18.958 | 0.151 | 0.259 | 0.880 | 2.032 | 0.005 | 0.013 | 47.911 | 15.942 | 0.381 |

| 28 | DY-1H | 4387.18 | P2w1 | 19.480 | 0.042 | 0.768 | 1.150 | 2.024 | 0.005 | 0.029 | 41.416 | 17.814 | 0.574 |

| 29 | DY-1H | 4388.01 | P2w1 | 6.993 | 0.009 | 0.442 | 0.940 | 3.293 | 0.072 | 0.027 | 56.525 | 19.055 | 0.227 |

| 30 | DY-1H | 4388.65 | P2w1 | 6.980 | 0.031 | 0.468 | 0.405 | 2.855 | 0.182 | 0.007 | 57.124 | 20.043 | 0.187 |

| 31 | DY-1H | 4389.12 | P2w1 | 6.191 | 0.011 | 0.580 | 0.337 | 2.948 | 0.084 | 0.006 | 61.518 | 17.486 | 0.206 |

| 32 | DY-1H | 4389.47 | P2w1 | 4.007 | 0.009 | 0.329 | 1.264 | 2.509 | 0.078 | 0.007 | 64.245 | 13.138 | 0.177 |

| 33 | DY-1H | 4389.75 | P2w1 | 7.462 | 0.067 | 0.557 | 0.478 | 3.780 | 0.082 | 0.004 | 56.059 | 18.850 | 0.246 |

| 34 | DY-1H | 4390.62 | P2w1 | 2.963 | 0.000 | 0.031 | 0.532 | 1.158 | 0.104 | 0.004 | 72.401 | 5.692 | 0.063 |

| 35 | DY-1H | 4392.04 | P2w1 | 2.203 | 0.024 | 0.011 | 28.319 | 1.032 | 0.117 | 1.891 | 28.834 | 6.813 | 0.087 |

| 36 | DY-1H | 4392.61 | P2w1 | 3.465 | 0.101 | 0.016 | 49.003 | 0.384 | 0.142 | 0.011 | 24.171 | 2.702 | 0.101 |

| 37 | DY-1H | 4394.00 | P2w1 | 0.900 | 0.015 | 0.000 | 16.606 | 0.121 | 0.032 | 0.006 | 58.460 | 0.834 | 0.115 |

| 38 | DY-1H | 4395.15 | P2w1 | 0.421 | 0.005 | 0.002 | 2.798 | 0.308 | 0.014 | 0.004 | 76.218 | 1.835 | 0.000 |

| Serial Number | Well Number | Well Depth | Formation | Ba (mg/kg) | Zr (mg/kg) | Sr (mg/kg) | Zn (mg/kg) | Cu (mg/kg) | Ni (mg/kg) | Cr (mg/kg) | V (mg/kg) | Co (mg/kg) | La (mg/kg) | Sc (mg/kg) | Th (mg/kg) | Mo (mg/kg) | U (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | DY-1H | 4328.21 | P2d1 | 4.2 | 71.0 | 619.0 | 84.3 | 62.9 | 199.3 | 312.3 | 199.0 | 13.7 | 6.4 | 4.3 | 5.1 | 3.1 | 4.5 |

| 2 | DY-1H | 4328.80 | P2d1 | 70.1 | 33.0 | 1161.0 | 48.4 | 65.0 | 97.9 | 257.1 | 90.7 | 26.3 | 9.8 | 6.2 | 6.3 | 2.5 | 4.3 |

| 3 | DY-1H | 4332.50 | P2d1 | 45.2 | 140.0 | 1436.0 | 112.2 | 103.2 | 121.0 | 212.3 | 97.6 | 25.3 | 22.5 | 6.5 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 4.6 |

| 4 | DY-1H | 4337.20 | P2d1 | 6.9 | 198.0 | 123.0 | 315.7 | 92.5 | 182.1 | 211.7 | 35.9 | 16.7 | 4.6 | 6.9 | 11.4 | 2.3 | 3.7 |

| 5 | DY-1H | 4337.45 | P2d1 | 70.5 | 118.0 | 738.0 | 160.9 | 78.7 | 131.4 | 112.7 | 18.5 | 22.8 | 18.3 | 5.7 | 10.1 | 2.7 | 3.9 |

| 6 | DY-1H | 4340.75 | P2d1 | 6.8 | 112.0 | 652.0 | 85.2 | 24.7 | 62.5 | 35.2 | 2.4 | 14.7 | 25.4 | 14.5 | 6.7 | 3.3 | 4.3 |

| 7 | DY-1H | 4340.78 | P2d1 | 3.8 | 51.0 | 792.0 | 61.0 | 19.7 | 41.1 | 22.3 | 0.0 | 19.8 | 30.9 | 5.7 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 3.8 |

| 8 | DY-1H | 4341.80 | P2d1 | 12.6 | 86.0 | 953.0 | 58.1 | 31.5 | 34.4 | 25.1 | 4.2 | 22.4 | 26.1 | 13.8 | 2.3 | 1.7 | 3.9 |

| 9 | DY-1H | 4344.40 | P2d1 | 26.5 | 52.0 | 666.0 | 15.2 | 30.9 | 14.8 | 28.6 | 4.7 | 13.6 | 22.8 | 12.6 | 5.8 | 3.6 | 4.5 |

| 10 | DY-1H | 4363.85 | P2w2 | 287.9 | 545.0 | 328.0 | 122.9 | 41.3 | 44.8 | 105.0 | 0.0 | 18.5 | 31.4 | 13.5 | 10.8 | 2.1 | 3.1 |

| 11 | DY-1H | 4364.70 | P2w2 | 303.0 | 530.0 | 248.0 | 118.6 | 31.2 | 43.3 | 91.8 | 0.0 | 16.1 | 20.7 | 9.7 | 6.5 | 2.3 | 4.2 |

| 12 | DY-1H | 4367.30 | P2w2 | 136.8 | 358.0 | 318.0 | 56.7 | 79.8 | 87.9 | 230.7 | 0.0 | 24.9 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 2.1 | 2.4 | 4.4 |

| 13 | DY-1H | 4367.79 | P2w2 | 111.6 | 342.0 | 240.0 | 64.1 | 60.6 | 76.6 | 143.0 | 0.0 | 14.8 | 8.0 | 4.1 | 4.4 | 2.6 | 3.3 |

| 14 | DY-1H | 4371.23 | P2w2 | 63.9 | 251.0 | 116.0 | 219.0 | 222.8 | 49.8 | 53.2 | 0.0 | 14.9 | 19.5 | 9.5 | 11.3 | 2.4 | 4.2 |

| 15 | DY-1H | 4371.76 | P2w2 | 30.8 | 200.0 | 129.0 | 174.1 | 410.7 | 45.8 | 47.2 | 0.0 | 24.0 | 27.8 | 8.7 | 5.5 | 2.8 | 5.3 |

| 16 | DY-1H | 4372.27 | P2w2 | 169.3 | 193.0 | 156.0 | 184.1 | 61.3 | 43.5 | 37.4 | 0.0 | 26.5 | 57.5 | 13.9 | 13.1 | 3.1 | 3.8 |

| 17 | DY-1H | 4373.22 | P2w1 | 13.3 | 217.0 | 190.0 | 136.7 | 220.6 | 53.8 | 49.8 | 0.0 | 30.7 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 0.3 | 2.5 | 4.1 |

| 18 | DY-1H | 4375.56 | P2w1 | 24.3 | 221.0 | 132.0 | 170.4 | 230.6 | 48.5 | 49.4 | 0.0 | 30.7 | 12.4 | 6.1 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 3.9 |

| 19 | DY-1H | 4377.94 | P2w1 | 10.3 | 314.0 | 109.0 | 126.3 | 166.1 | 49.9 | 59.9 | 0.0 | 18.3 | 41.8 | 8.4 | 17.9 | 2.4 | 6.2 |

| 20 | DY-1H | 4378.60 | P2w1 | 22.8 | 196.0 | 96.0 | 76.6 | 98.5 | 32.2 | 22.6 | 0.0 | 22.6 | 27.3 | 6.6 | 4.3 | 2.6 | 4.5 |

| 21 | DY-1H | 4379.46 | P2w1 | 0.9 | 222.0 | 196.0 | 82.4 | 200.9 | 34.0 | 48.9 | 0.0 | 18.8 | 18.2 | 6.5 | 3.7 | 2.7 | 3.4 |

| 22 | DY-1H | 4380.24 | P2w1 | 82.3 | 970.0 | 293.0 | 39.9 | 81.0 | 30.5 | 38.8 | 0.0 | 22.2 | 43.2 | 4.0 | 1.5 | 2.9 | 3.6 |

| 23 | DY-1H | 4381.54 | P2w1 | 161.0 | 925.0 | 249.0 | 62.5 | 113.7 | 28.4 | 29.7 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 82.8 | 14.6 | 12.2 | 2.5 | 3.5 |

| 24 | DY-1H | 4381.80 | P2w1 | 6.2 | 1001.0 | 274.0 | 43.8 | 114.7 | 26.4 | 31.4 | 0.0 | 15.2 | 11.5 | 5.2 | 7.9 | 3.2 | 5.4 |

| 25 | DY-1H | 4382.22 | P2w1 | 14.1 | 930.0 | 275.0 | 59.6 | 98.8 | 30.7 | 32.0 | 0.0 | 14.4 | 15.6 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 3.3 | 4.3 |

| 26 | DY-1H | 4382.45 | P2w1 | 76.0 | 1033.0 | 279.0 | 78.2 | 231.5 | 38.3 | 35.5 | 0.0 | 25.8 | 32.2 | 8.2 | 5.0 | 2.3 | 4.1 |

| 27 | DY-1H | 4385.77 | P2w1 | 4.6 | 506.0 | 218.0 | 123.4 | 24.9 | 39.5 | 84.5 | 0.0 | 14.1 | 20.2 | 7.0 | 6.5 | 2.5 | 3.6 |

| 28 | DY-1H | 4387.18 | P2w1 | 142.3 | 500.0 | 265.0 | 71.4 | 76.8 | 35.4 | 95.8 | 0.0 | 133.5 | 143.8 | 25.4 | 12.9 | 2.6 | 4.9 |

| 29 | DY-1H | 4388.01 | P2w1 | 7.1 | 463.0 | 328.0 | 23.0 | 61.7 | 45.9 | 22.7 | 0.0 | 61.5 | 4.0 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 2.8 | 5.8 |

| 30 | DY-1H | 4388.65 | P2w1 | 48.2 | 505.0 | 245.0 | 98.0 | 105.1 | 44.0 | 28.9 | 0.0 | 17.2 | 38.0 | 9.5 | 10.5 | 2.3 | 5.7 |

| 31 | DY-1H | 4389.12 | P2w1 | 73.4 | 431.0 | 232.0 | 124.2 | 178.8 | 53.7 | 95.3 | 0.0 | 21.9 | 10.2 | 7.7 | 4.5 | 2.2 | 3.5 |

| 32 | DY-1H | 4389.47 | P2w1 | 161.7 | 256.0 | 244.0 | 17.9 | 124.1 | 43.4 | 136.1 | 13.3 | 8.6 | 19.4 | 6.4 | 6.7 | 2.5 | 5.3 |

| 33 | DY-1H | 4389.75 | P2w1 | 57.5 | 356.0 | 218.0 | 29.2 | 73.1 | 28.8 | 125.3 | 0.0 | 16.5 | 21.6 | 9.2 | 5.9 | 2.6 | 4.6 |

| 34 | DY-1H | 4390.62 | P2w1 | 78.7 | 68.0 | 76.0 | 15.0 | 57.1 | 37.7 | 932.1 | 98.4 | 25.1 | 16.1 | 8.8 | 5.4 | 2.9 | 3.9 |

| 35 | DY-1H | 4392.04 | P2w1 | 133.1 | 34.0 | 737.0 | 205.1 | 40.7 | 205.1 | 374.7 | 45.9 | 20.1 | 18.5 | 7.9 | 10.2 | 3.2 | 5.8 |

| 36 | DY-1H | 4392.61 | P2w1 | 153.1 | 32.0 | 426.0 | 15.3 | 25.8 | 30.2 | 45.4 | 12.3 | 13.1 | 14.4 | 3.9 | 5.6 | 3.1 | 5.5 |

| 37 | DY-1H | 4394.00 | P2w1 | 7.1 | 8.0 | 182.0 | 5.4 | 10.0 | 14.1 | 15.2 | 4.9 | 22.6 | 16.7 | 7.3 | 11.3 | 2.4 | 3.7 |

| 38 | DY-1H | 4395.15 | P2w1 | 9.5 | 11.0 | 59.0 | 18.7 | 6.2 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 0.0 | 19.2 | 24.9 | 6.8 | 13.4 | 2.9 | 3.9 |

| Formation | BaEF | CuEF | ZnEF | NiEF | Number of Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dalong | (0.21–0.48/0.40) | (1.54–8.63/4.99) | (1.13–5.35/2.91) | (1.34–8.78/3.71) | (9) |

| Wujiaping | (0.027–1.66/0.52) | (0.92–21.87/5.33) | (0.27–6.65/1.66) | (0.30–8.11/1.26) | (29) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Xu, L.; Li, H.; Zhang, M.; Liu, S.; Xu, L.; Liu, D.; Xia, T.; Wang, J. Organic Matter Enrichment and Reservoir Nanopore Characteristics of Marine Shales: A Case Study of the Permian Shales in the Kaijiang–Liangping Trough. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241870

Yang X, Xu L, Li H, Zhang M, Liu S, Xu L, Liu D, Xia T, Wang J. Organic Matter Enrichment and Reservoir Nanopore Characteristics of Marine Shales: A Case Study of the Permian Shales in the Kaijiang–Liangping Trough. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241870

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xinrui, Liangjun Xu, Huilin Li, Mingkai Zhang, Sirui Liu, Lu Xu, Dongxi Liu, Tong Xia, and Jia Wang. 2025. "Organic Matter Enrichment and Reservoir Nanopore Characteristics of Marine Shales: A Case Study of the Permian Shales in the Kaijiang–Liangping Trough" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241870

APA StyleYang, X., Xu, L., Li, H., Zhang, M., Liu, S., Xu, L., Liu, D., Xia, T., & Wang, J. (2025). Organic Matter Enrichment and Reservoir Nanopore Characteristics of Marine Shales: A Case Study of the Permian Shales in the Kaijiang–Liangping Trough. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1870. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241870