One-Stage Synthesis of Superhydrophobic SiO2 Particles for Struvite-Based Dry Powder Coating of Extinguishing Agent

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Used for Synthesis

2.2. Synthesis Methods

- -

- introduction of a hydrophobizing compound into the reaction mixture before the source of silicon dioxide (method 1, samples S11–S51);

- -

- introduction of a hydrophobizing compound into the reaction mixture through a non-polar migration agent after a source of silicon dioxide and the formation of a SiO2-gel, (method 2, samples S12–S52).

2.3. Methods of Sample Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

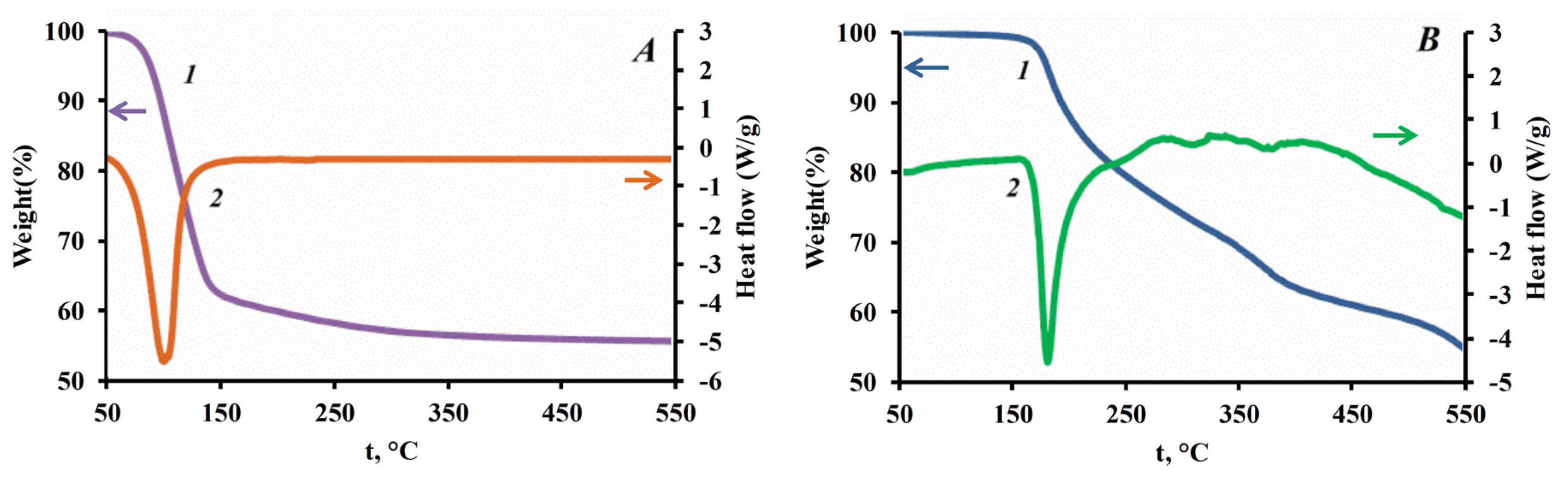

3.1. Functional Additive Particles Characterization

3.2. Rheological Characteristics of Fire Extinguishing Compositions

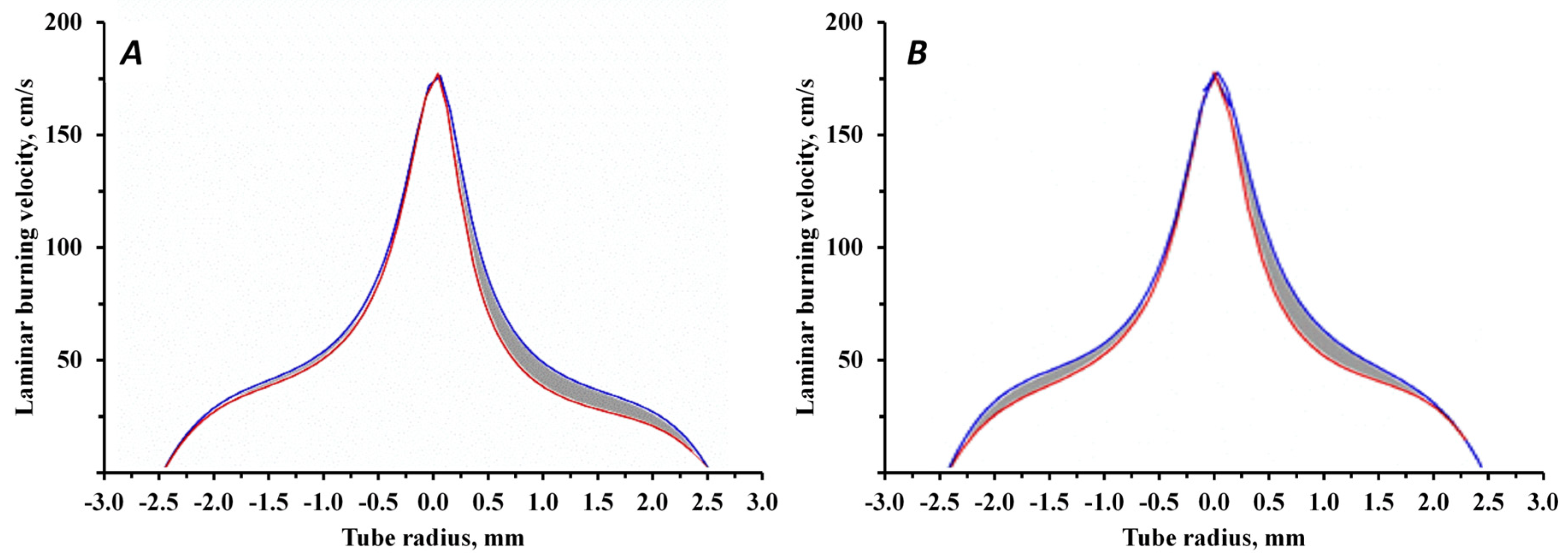

3.3. Evaluation of the Compositions’ Ability to Inhibit Flames

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FEP | fire extinguishing powder |

| FEPS | fire extinguishing powder based on struvite |

| FEPS | fire extinguishing powder based on monoammonium phosphate |

| MAP | monoammonium phosphate |

| TEOS | tetraethoxysilane |

| PMHS | polymethylhydrosiloxane |

References

- Karyakin, A.V.; Muradova, G.A.; Maisuradze, G.V. IR spectroscopic study of the interaction of water with silanol groups. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 1970, 12, 675–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jentys, A.; Kleestorfer, K.; Vinek, H. Concentration of surface hydroxyl groups on MCM-41. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 1999, 27, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burneau, A.; Carteret, C. Near infrared and Ab Initio Study of the vibrational modes of isolated silanol on silica. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2000, 2, 3217–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christy, A.A.; Egeberg, P.K. Quantitative determination of surface silanol groups in silicagel by deuterium exchange combined with infrared spectroscopy and Chemometrics. Analyst 2005, 130, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casanovas, J.; Illas, F.; Pacchioni, G. Ab initio calculations of 29Si solid state NMR chemical shifts of silane and silanol groups in silica. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2000, 326, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ek, S. Determination of the hydroxyl group content in silica by thermogravimetry and a comparison with 1H MAS NMR results. Thermochim. Acta 2001, 379, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potapov, V.V.; Zhuravlev, L.T. Temperature dependence of the concentration of silanol groups in silica precipitated from a hydrothermal solution. Glass Phys. Chem. 2005, 31, 661–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunin, A.V.; Smirnov, S.A.; Lapshin, D.N.; Semenov, A.D.; Il’iN, A.P. Technology development for the production of ABCE fire extinguishing dry powders. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2016, 86, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lida, K.; Hayakawa, Y.; Okamoto, H.; Danjo, K.; Leuenberger, H. Evaluation of flow properties of dry powder inhalation of salbutamol sulfate with lactose carrier. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2001, 49, 1326–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, M.-J.; Grandbois, M.; Abatzoglou, N. Identification of inter-particular forces by atomic force microscopy and how they relate to powder rheological properties measured in shearing tests. Powder Technol. 2015, 284, 396–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, L.; Morton, D.; Zhou, Q. Particle Engineering via mechanical dry coating in the design of pharmaceutical solid dosage forms. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2015, 21, 5802–5814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karde, V.; Panda, S.; Ghoroi, C. Surface modification to improve powder bulk behavior under humid conditions. Powder Technol. 2015, 278, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, T.; Elliott, J.A. Effect of silica nanoparticles on the bulk flow properties of fine cohesive powders. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2013, 101, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrashova, N.B.; Shamsutdinov, A.S.; Valtsifer, I.V.; Starostin, A.S.; Valtsifer, V.A. Hydrophobized silicas as functional fillers of fire-extinguishing powders. Inorg. Mater. 2018, 54, 1078–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrashova, N.B.; Val’tsifer, I.V.; Shamsutdinov, A.S.; Starostin, A.S.; Val’tsifer, V.A. Control over rheological properties of powdered formulations based on phosphate-ammonium salts and hydrophobized silicon oxide. Russ. J. Appl. Chem. 2017, 90, 1592–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saenko, E.V.; Huo, Y.; Shamsutdinov, A.S.; Kondrashova, N.B.; Valtsifer, I.V.; Valtsifer, V.A. Mesoporous hydrophobic silica nanoparticles as flow-enhancing additives for fire and explosion suppression formulations. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 2221–2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rheological Additive for Fire-Extinguishing Powder Formulations. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2723518C2/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Shamsutdinov, A.S.; Kondrashova, N.B.; Valtsifer, I.V.; Bormashenko, E.; Huo, Y.; Saenko, E.V.; Pyankova, A.V.; Valtsifer, V.A. Manufacturing, properties, and application of Nanosized superhydrophobic spherical silicon dioxide particles as a functional additive to fire extinguishing powders. ACS Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 11905–11914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fire-Extinguishing Powder Composition. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2615715C1/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Yan, C.; Pan, X.; Hua, M.; Li, S.; Guo, X.; Zhang, C. Study on the fire extinguishing efficiency and mechanism of composite superfine dry powder containing ferrocene. Fire Saf. J. 2022, 130, 103606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combined Composition for Firefighting, Method for Combined Firefighting and Microcapsulated Extinguishing Agent. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2622303C1/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- High-Performance Fire Extinguishing Agent. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN1397360A/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Zhang, C.; Li, H.; Guo, X.; Li, S.; Zhang, H.; Pan, X.; Hua, M. Experimental and theoretical studies on the effect of Al(OH)3 on the fire-extinguishing performance of superfine ABC Dry powder. Powder Technol. 2021, 393, 280–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Composition for Producing a Combined Gas-Powder Fire Extinguishing Composition. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2670297C2/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Thermally Activated Fire Extinguishing Powder. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2583365C1/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Aerosol-Forming Composition and Fire-Extinguishing Aerosol Generator. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2201774C2/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Dry Powder Fire Extinguishing Agent. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN102512779B/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Novel Fire-Extinguishing Composition. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/CN102949799B/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Method for Manufacturing Fire Extinguishant. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/WO2017094918A1/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Wang, Q.; Wang, F.; Li, C.; Li, Z.; Li, R. Fire extinguishing performance and mechanism for several typical dry water extinguishing agents. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 9827–9836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Yu, R.; Chang, Z.; Tan, Z.; Liu, X. The fire extinguishing mechanism of ultrafine composite dry powder agent containing Mg(OH)2. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2021, 121, e26810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Sun, Y.; Huang, Y.; Guo, X.; Cai, G.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H. Fire extinguishing performance of chemically bonded struvite ceramic powder with high heat-absorbing and flame retardant properties. Materials 2022, 15, 8021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P’yankova, A.V.; Kondrashova, N.B.; Val’tsifer, I.V.; Shamsutdinov, A.S.; Bormashenko, E.Y. Synthesis and thermal behavior of a struvite-based fine powder fire-extinguishing agent. Inorg. Mater. 2021, 57, 1083–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataki, S.; West, H.; Clarke, M.; Baruah, D. Phosphorus recovery as Struvite: Recent concerns for use of seed, alternative mg source, nitrogen conservation and fertilizer potential. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 107, 142–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wan, Y.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, P.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H. Preparation and fire extinguishing mechanism of novel fire extinguishing powder based on recyclable struvite. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jin, Q.; Zhang, X. Structural modification of ammonium polyphosphate by dopo to achieve high water resistance and hydrophobicity. Powder Technol. 2017, 320, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Liu, H.; Zong, R.; Lo, S.-M. Study of a new type of fire suppressant powder of Mg(OH)2 modified by Dopo-VTS. Procedia Eng. 2018, 211, 1102–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yin, Z.; Usman Shahid, M.; Xing, H.; Cheng, X.; Fu, Y.; Lu, S. Superhydrophobic and oleophobic ultra-fine dry chemical agent with higher chemical activity and longer fire-protection. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 380, 120625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtsifer, I.V.; Huo, Y.; Zamashchikov, V.V.; Shamsutdinov, A.S.; Kondrashova, N.B.; Sivtseva, A.V.; Pyankova, A.V.; Valtsifer, V.A. Synthesis of hydrophobic nanosized silicon dioxide with a spherical particle shape and its application in fire-extinguishing powder compositions based on struvite. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, Y.; Valtsifer, I.V.; Shamsutdinov, A.S. Synthesis and application of hydrophobic silicon dioxide to improve the rheological properties of fire extinguishing compositions based on struvite. Combust. Explos. Shock. Waves 2023, 59, 733–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Complex Functional Filler for Fire Extinguishing Powder Composition. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2837871C1/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Method for Producing Fire Extinguishing Powder Composition with Increased Cooling Effect. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/RU2792529C1/en (accessed on 28 September 2025).

- Freeman, R.E.; Cooke, J.R.; Schneider, L.C.R. Measuring shear properties and normal stresses generated within a rotational shear cell for consolidated and non-consolidated powders. Powder Technol. 2009, 190, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. Measuring the flow properties of consolidated, conditioned and aerated powders—a comparative study using a powder rheometer and a rotational shear cell. Powder Technol. 2007, 174, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.-N.; Lu, H.-F.; Guo, X.-L.; Gong, X. Study on the effect of nanoparticles on the bulk and flow properties of granular systems. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 177, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Du, S.; Yao, S.; Guo, Y.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H. Enhanced fire-extinguishing performance of struvite powder through modulation of its thermal-decomposition characteristics. Fire Saf. J. 2025, 159, 104594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Molar Ratios | Introduction of PMHS into the Reaction Mixture | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TEOS | PMHS | NH4OH | C2H5OH | H2O | Before TEOS (Method 1) | After TEOS and the Formation of a SiO2-gel (Method 2) | ||

| Sample | Size, nm | Sample | Size, nm | |||||

| 1 | 0.006 | 1.5 | 9.5 | 32 | S11 | Continuously porous structure | S12 | 40 |

| 1 | 0.006 | 1.5 | 9.5 | 28 | S21 | S22 | 50 | |

| 1 | 0.006 | 1.5 | 9.5 | 25 | S31 | S32 | 100 | |

| 1 | 0.006 | 1.5 | 9.5 | 22 | S41 | S42 | 200 | |

| 1 | 0.006 | 1.5 | 9.5 | 19 | S51 | S52 | 500 | |

| Method | Sample | H2O/Ethanol (mole) Ratio | SBET, m2/g | Vtot, cm3/g | Pore Diameter (BJH), nm | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Desorption | |||||

| 1 | S11 | 32 | 512 | 0.69 | 4.7 | 4.4 |

| S21 | 28 | 489 | 0.71 | 4.7 | 5.2 | |

| S31 | 25 | 481 | 0.74 | 5.7 | 6.0 | |

| S41 | 22 | 439 | 0.87 | 5.9 | 6.4 | |

| S51 | 19 | 349 | 0.61 | 5.3 | 4.9 | |

| 2 | S12 | 32 | 37 | 0.33 | 24 | 26 |

| S22 | 28 | 23 | 0.03 | 4.8 | 5.5 | |

| S32 | 25 | 20 | 0.02 | 5.7 | 4.8 | |

| S42 | 22 | 3 | 0.01 | 13.2 | 6.6 | |

| S52 | 19 | 3 | 0.01 | 15 | 9 | |

| Sample | H2O/TEOS | SBET, m2/g | Smicropores (t-Plot), m2/g | Vtot, cm3/g | Dpor, nm | D, nm | Mass Loss 200–1000 °C, % (TGA) | Amount of Silanol Groups, mmol/g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1-0 | 32 | 255 ± 5.6 | 44 | 0.97 | 14 | 50 | 3.7 | 4.11 |

| S2-0 | 28 | 225 ± 7.6 | 134 | 0.37 | 20 | 120 | 3.9 | 4.33 |

| S3-0 | 25 | 232 ± 8.4 | 151 | 0.26 | 18 | 200 | 4.1 | 4.56 |

| S4-0 | 22 | 249 ± 9.4 | 190 | 0.17 | 6 | 300 | 4.3 | 4.78 |

| S5-0 | 19 | 34 ± 0.26 | 27 | 0.05 | 8 | 400 | 4.5 | 5.00 |

| H2O/ TEOS (mole) Ratio | One-Step Method for Hydrophobic SiO2 Synthesis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method 1 | Method 2 | |||

| Sample | Wetting Angle, ° | Sample | Wetting Angle, ° | |

| 32 | S11 | 153.2 ± 1.2 | S12 | 162.3 ± 0.3 |

| 28 | S21 | 152.8 ± 0.9 | S22 | 163.0 ± 1.2 |

| 25 | S31 | 163.4 ± 1.7 | S32 | 152.6 ± 0.8 |

| 22 | S41 | 162.1 ± 1.6 | S42 | 148.0 ± 1.4 |

| 19 | S51 | 155.8 ± 1.2 | S52 | 147.4 ± 1.4 |

| Sample | Wetting Angle, ° |

|---|---|

| FEPS-S11 | - |

| FEPS-S12 | 160.7 ± 0.5 |

| FEPS-S32 | 152.8 ± 0.3 |

| FEPS-S42 | 148.3 ± 0.2 |

| FEPP-S12 | 160.2 ± 0.2 |

| FEP Sample | Functional Additive | Cohesion, kPa | Flow Function Coefficient (ffc) |

|---|---|---|---|

| struvite | - | 2.53 ± 0.05 | 1.75 |

| FEPS-S11 | S11 | 0.746 ± 0.04 | 5.97 |

| FEPS-S12 | S12 | 0.420 ± 0.02 | 10.70 |

| FEPS-S32 | S32 | 0.489 ± 0.06 | 9.07 |

| FEPS-S42 | S42 | 0.932 ± 0.03 | 4.47 |

| FEPP-S12 | S12 | 0.506 ± 0.05 | 8.30 |

| FEP Sample | Particle Density in Flame (Particles/mm2) in 1 s Interval | Laminar Burning Velocity Reduction, % | Heat Adsorption, J/g |

|---|---|---|---|

| FEPS-S12 | 200 | 25.85 | 773.5 |

| FEPP-S12 | 450 | 29.07 | 1432.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Valtsifer, I.; Huo, Y.; Zamashchikov, V.; Shamsutdinov, A.; Saenko, E.; Kondrashova, N.; Averkina, A.; Valtsifer, V. One-Stage Synthesis of Superhydrophobic SiO2 Particles for Struvite-Based Dry Powder Coating of Extinguishing Agent. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241859

Valtsifer I, Huo Y, Zamashchikov V, Shamsutdinov A, Saenko E, Kondrashova N, Averkina A, Valtsifer V. One-Stage Synthesis of Superhydrophobic SiO2 Particles for Struvite-Based Dry Powder Coating of Extinguishing Agent. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241859

Chicago/Turabian StyleValtsifer, Igor, Yan Huo, Valery Zamashchikov, Artem Shamsutdinov, Ekaterina Saenko, Natalia Kondrashova, Anastasiia Averkina, and Viktor Valtsifer. 2025. "One-Stage Synthesis of Superhydrophobic SiO2 Particles for Struvite-Based Dry Powder Coating of Extinguishing Agent" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241859

APA StyleValtsifer, I., Huo, Y., Zamashchikov, V., Shamsutdinov, A., Saenko, E., Kondrashova, N., Averkina, A., & Valtsifer, V. (2025). One-Stage Synthesis of Superhydrophobic SiO2 Particles for Struvite-Based Dry Powder Coating of Extinguishing Agent. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1859. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241859