The Impact of the Reducing Agent on the Cytotoxicity and Selectivity Index of Silver Nanoparticles in Leukemia and Healthy Cells

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs)

2.2.1. GLU-AgNPs

2.2.2. PVP-AgNPs

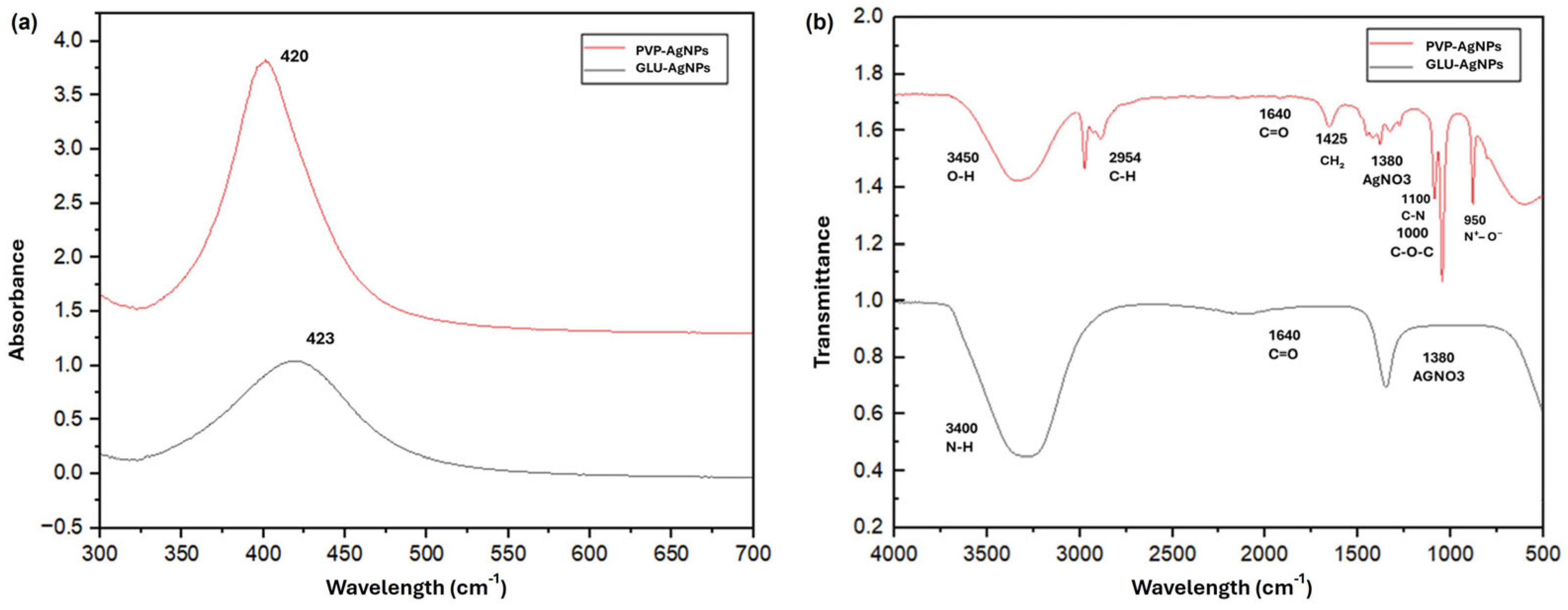

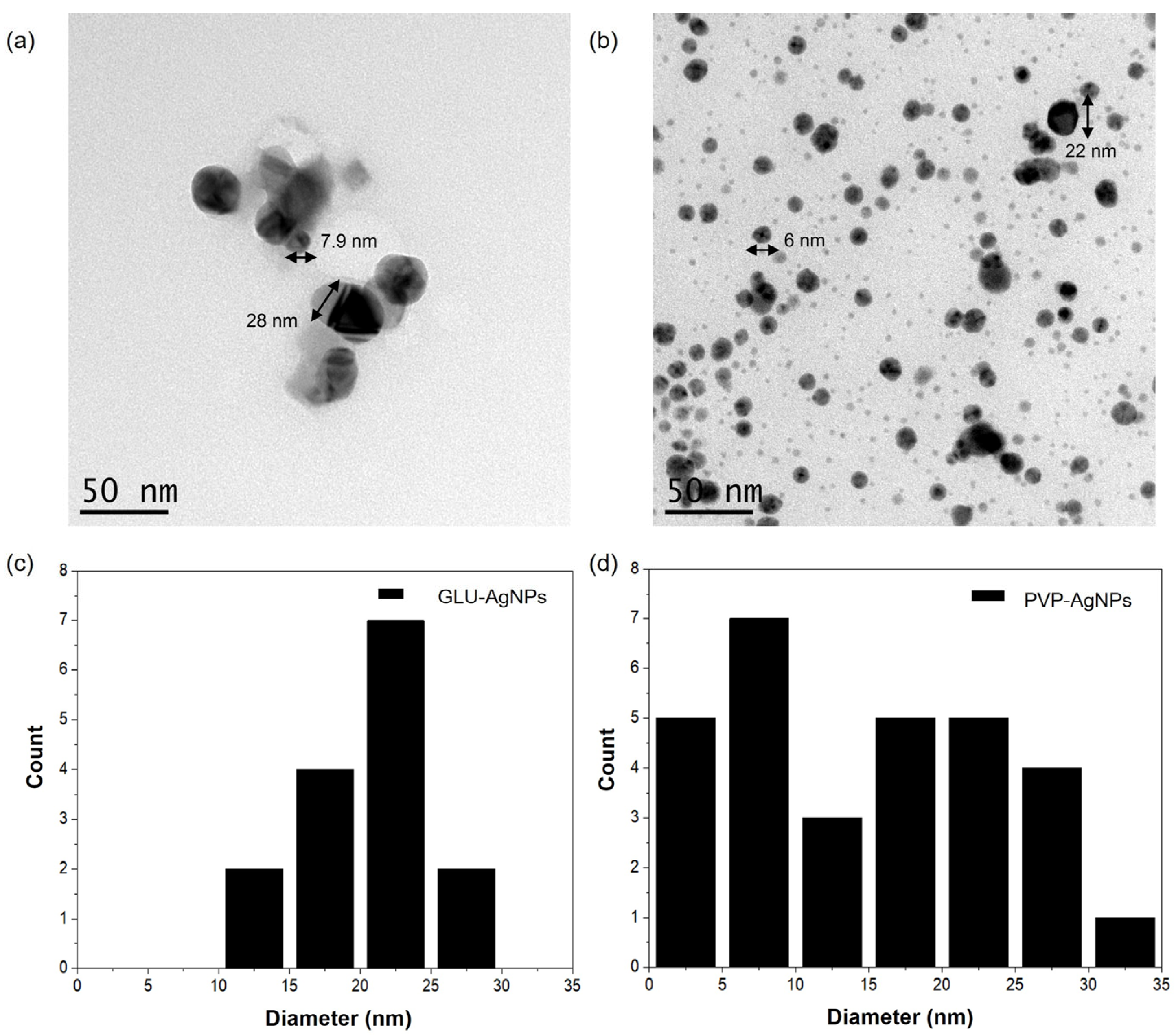

2.2.3. Physicochemical and Morphological Characterization of AgNPs

2.3. Cell Culture and Treatment Conditions

2.4. Cell Viability Assay, IC50, and Selectivity Index

2.5. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles

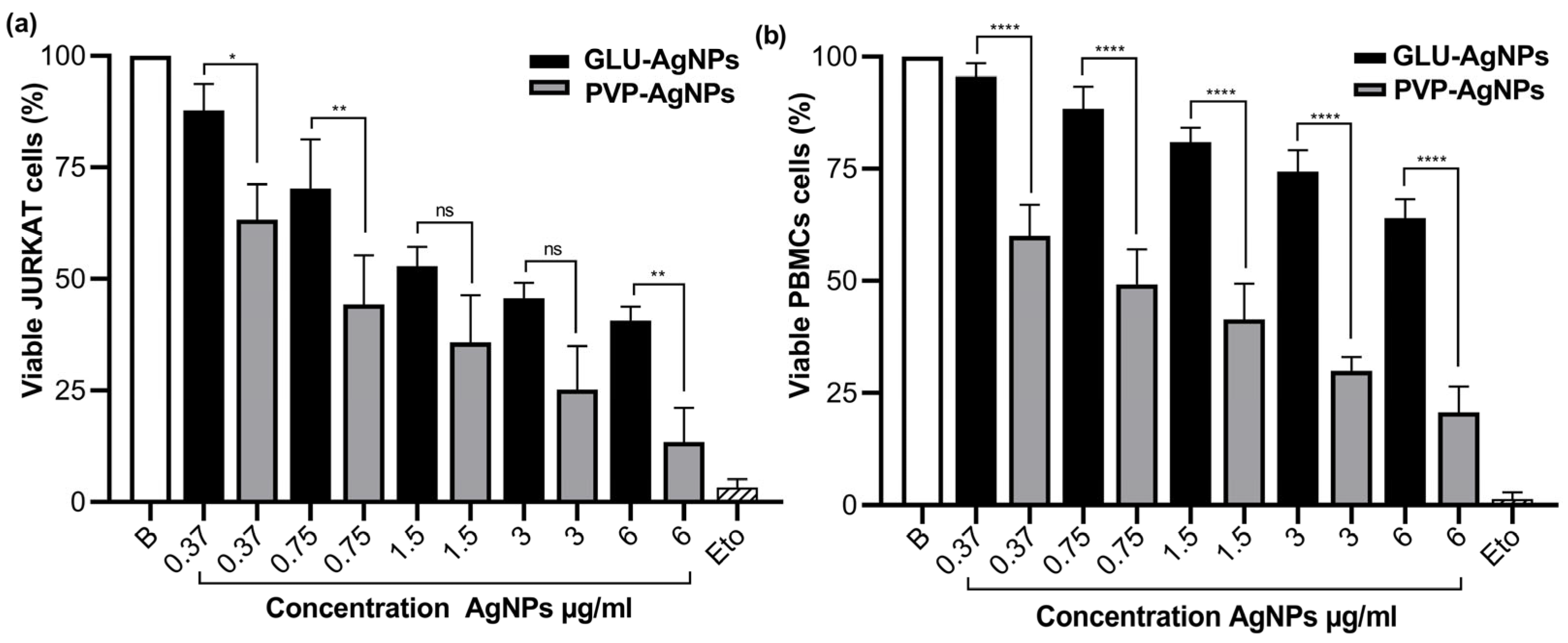

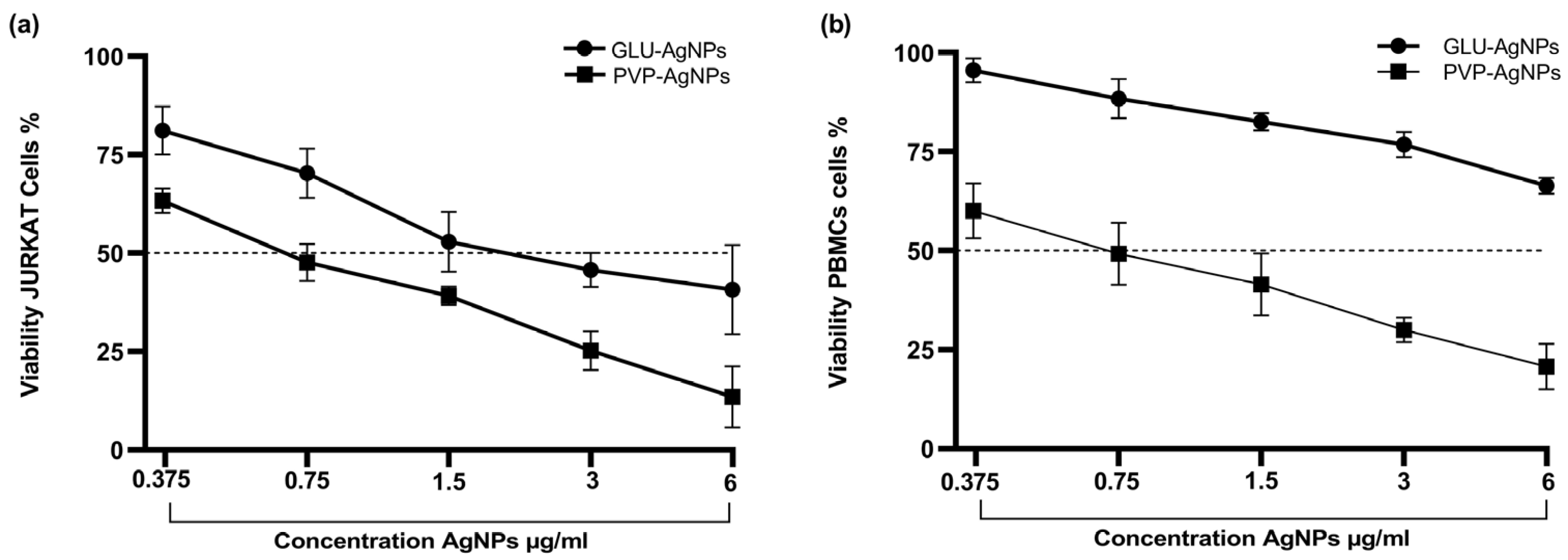

3.2. Cell Viability and IC50

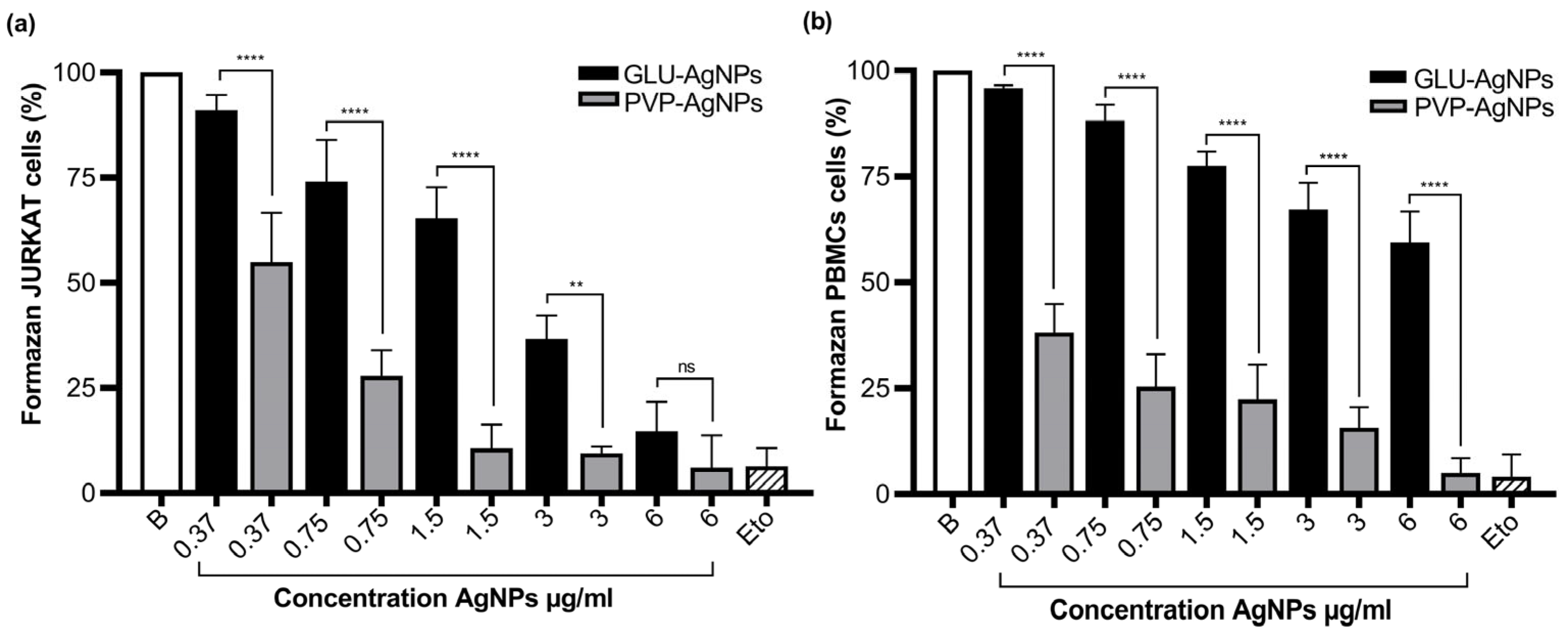

3.3. Cytotoxicity in JURKAT and PBMCs Stimulated with GLU-AgNPs and PVP-AgNPs

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AgNPs | Silver Nanoparticles |

| GLU | Glucose |

| PVP | Polyvinylpyrrolidone |

| PBMCs | Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells |

| SPR | Surface Plasmon Resonance |

| FTIR | Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| TEM | Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| DLS | Dynamic Light Scattering |

| MTT | 3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide |

| IC50 | Half-Maximal Inhibitory Concentration |

| SI | Selectivity Index |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| CUCS | Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud |

| INICIA | Instituto de Investigación en Cáncer en la Infancia y Adolescencia |

| IICB | Instituto de Investigación en Ciencias Biomédicas |

References

- Ahamed, M.S.; AlSalhi, M.K.J.; Siddiqui, M. Silver nanoparticle applications and human health. Clin. Chim. Acta 2010, 411, 1841–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávalos, A.; Haza, A.; Morales, P. Nanopartículas de plata: Aplicaciones y riesgos tóxicos para la salud humana y el medio ambiente. Rev. Complut. Cienc. Veter 2013, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Singh, S.; Ravichandiran, V. Toxicity, preparation methods and applications of silver nanoparticles: An update. Toxicol. Mech. Methods 2022, 32, 650–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horie, M.; Kato, H.; Fujita, K.; Endoh, S.; Iwahashi, H. In Vitro Evaluation of Cellular Response Induced by Manufactured Nanoparticles. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2011, 25, 605–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkevich, J.; Stevenson, P.C.; Hillier, J. A study of the nucleation and growth processes in the synthesis of colloidal gold. Discuss. Faraday Soc. 1951, 11, 55–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, H.-J.; Choi, J. p38 MAPK Activation, DNA Damage, Cell Cycle Arrest and Apoptosis As Mechanisms of Toxicity of Silver Nanoparticles in Jurkat T Cells. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 8337–8342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rónavári, A.; Bélteky, P.; Boka, E.; Zakupszky, D.; Igaz, N.; Szerencsés, B.; Pfeiffer, I.; Kónya, Z.; Kiricsi, M. Polyvinyl-Pyrrolidone-Coated Silver Nanoparticles—The Colloidal, Chemical, and Biological Consequences of Steric Stabilization under Biorelevant Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra Hurtado, J.M.; Virgen Ortiz, A.; Irebe, A.; Luna Velasco, A. Control and stabilization of silver nanoparticles size using poly-vinylpyrrolidone at room temperature. Digest. J. Nanomater. Biostruct. 2014, 9, 493–501. [Google Scholar]

- Sulaiman, G.M.; Mohammed, W.H.; Marzoog, T.R.; Al-Amiery, A.A.A.; Kadhum, A.A.H.; Mohamad, A.B. Green synthesis, antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of silver nanoparticles using Eucalyptus chapmaniana leaves extract. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2013, 3, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S.; Shahri, M.M. Medical and cytotoxicity effects of green synthesized silver nanoparticles using Achillea millefolium extract on MOLT-4 lymphoblastic leukemia cell line. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 3899–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.X.; Wong, H.L.; Xue, H.Y.; Eoh, J.Y.; Wu, X.Y. Nanomedicine of synergistic drug combinations for cancer therapy—Strategies and perspectives. J. Control Release 2016, 240, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Morales, S.; Hidalgo-Miranda, A.; Ramírez-Bello, J. Leucemia linfoblástica aguda infantil: Una aproximación genómica. Boletin. Medico Del Hosp. Infant. De Mex. 2017, 74, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greulich, C.; Diendorf, J.; Geßmann, J.; Simon, T.; Habijan, T.; Eggeler, G.; Schildhauer, T.; Epple, M.; Köller, M. Cell type-specific responses of peripheral blood mononuclear cells to silver nanoparticles. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 3505–3514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguilar-Méndez, M.A.; Martín-Martínez, E.S.; Ortega-Arroyo, L.; Cobián-Portillo, G.; Sánchez-Espíndola, E. Synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles: Effect on phytopathogen Colletotrichum gloesporioides. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2010, 13, 2525–2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler-Toledo International Inc. Espectroscopia Ultravioleta-Visible: Conceptos Básicos. 10 November 2022 [citado 2023]. Available online: https://www.mt.com/mx/es/home/applications/application_browse_laboratory_analytics/uv-vis-spectroscopy/uvvis-spectroscopy-explained.html (accessed on 15 August 2025).

- Jara, N.; Milán, N.S.; Rahman, A.; Mouheb, L.; Boffito, D.C.; Jeffryes, C.; Dahoumane, S.A. Photochemical Synthesis of Gold and Silver Nanoparticles—A Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malvern Instruments. Zeta Potential—An Introduction in 30 Minutes. Worcestershire, UK. 2015, pp. 1–15. Available online: https://www.research.colostate.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/ZetaPotential-Introduction-in-30min-Malvern.pdf (accessed on 6 September 2023).

- Terwilliger, T.; Abdul-Hay, M. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A comprehensive review and 2017 update. Blood Cancer J. 2017, 7, e577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurunathan, S.; Qasim, M.; Park, C.; Yoo, H.; Choi, D.Y.; Song, H.; Park, C.; Kim, J.-H.; Hong, K. Cytotoxicity and Transcriptomic Analysis of Silver Nanoparticles in Mouse Embryonic Fibroblast Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laime-Oviedo, L.A.; Soncco-Ccahui, A.A.; Peralta-Alarcon, G.; Arenas-Chávez, C.A.; Pineda-Tapia, J.L.; Díaz-Rosado, J.C.; Alvarez-Risco, A.; Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S.; Davies, N.M.; Yáñez, J.A.; et al. Optimization of Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Conjugated with Lepechinia meyenii (Salvia) Using Plackett-Burman Design and Response Surface Methodology—Preliminary Antibacterial Activity. Processes 2022, 10, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Contreras, R.; Costa-Torres, M.C.; Arenas-Arrocena, M.C.; Rodríguez Torres, M.P. Manual Para la Enseñanza Práctica del Ensayo MTT Para Evaluar la Citotoxicidad de Nanopartículas; ResearchGate—Unidad León, UNAM: León de los Aldama, México, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, G.; Mishra, M. Development and optimization of UV-VIS spectroscopy, a review. World J. Pharm. Res. 2018, 7, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Neto, F.N.S.; Morais, L.A.; Gorup, L.F.; Ribeiro, L.S.; Martins, T.J.; Hosida, T.Y.; Francatto, P.; Barbosa, D.B.; Camargo, E.R.; Delbem, A.C.B. Facile Synthesis of PVP-Coated Silver Nanoparticles and Evaluation of Their Physicochemical, Antimicrobial and Toxic Activity. Colloids Interfaces 2023, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.-F.; Liu, Z.-G.; Shen, W.; Gurunathan, S. Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Characterization, Properties, Applications, and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nymark, P.; Catalán, J.; Suhonen, S.; Järventaus, H.; Birkedal, R.; Clausen, P.A.; Jensen, K.A.; Vippola, M.; Savolainen, K.; Norppa, H. Genotoxicity of polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated silver nanoparticles in BEAS 2B cells. Toxicology 2013, 313, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagdale, S.; Narwade, M.; Sheikh, A.; Shadab; Salve, R.; Gajbhiye, V.; Kesharwani, P.; Gajbhiye, K.R. GLUT1 transporter-facilitated solid lipid nanoparticles loaded with anti-cancer therapeutics for ovarian cancer targeting. Int. J. Pharm. 2023, 637, 122894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Yuan, H. Targeting Glucose Transporter 1 (GLUT1) in Cancer: Molecular Mechanisms and Nanomedicine Applications. Int. J. Nanomed. 2025, 20, 11859–11879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Pujari, G.; Sarma, A.; Mishra, Y.K.; Jin, M.K.; Nirala, B.K.; Gohil, N.K.; Adelung, R.; Avasthi, D.K. Study Of In Vitro Toxicity Of Glucose Capped Gold nanoparticles In Malignant And Normal Cell Lines. Adv. Mater. Lett. 2013, 4, 888–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tatar, A.-S.; Nagy-Simon, T.; Tomuleasa, C.; Boca, S.; Astilean, S. Nanomedicine approaches in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Control Release 2016, 238, 123–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourhoseini, S.; Enos, R.T.; Murphy, A.E.; Cai, B.; Lead, J.R. Characterization, bio-uptake and toxicity of polymer-coated silver nanoparticles and their interaction with human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 2021, 12, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jamil, A.; Geso, M.; Algethami, M.; Sohaimi, W.F.W.; Razak, K.A.; Rahman, W.N. The effect of polyvinylpyrrolidone-coated (PVP) on bismuth-based nanoparticles cell cytotoxicity. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 66, 2948–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Property | GLU-AgNPs | PVP-AgNPs |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrodynamic diameter (nm) | 22.4 ± 1.20 | 30 ± 1.8 |

| Polydispersity index (PDI) | 0.232 | 0.280 |

| Zeta potential (mV) | −3.50 | −10.01 |

| Cell Type | AgNPs | IC50 (μg/mL) | SI |

|---|---|---|---|

| JURKAT | GLU-AgNPs | 2.830 | 2.439 |

| PVP-AgNPs | 0.309 | ||

| PBMCs | GLU-AgNPs | 6.910 | 0.361 |

| PVP-AgNPs | 0.854 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aguirre-León, J.G.; Sulbarán-Rangel, B.; Pérez-Guerrero, E.E.; Topete-Camacho, A.; García-Iglesias, T.; Sánchez-Hernández, P.E.; Ramos-Solano, M.; Machado-Sulbaran, A.C. The Impact of the Reducing Agent on the Cytotoxicity and Selectivity Index of Silver Nanoparticles in Leukemia and Healthy Cells. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241858

Aguirre-León JG, Sulbarán-Rangel B, Pérez-Guerrero EE, Topete-Camacho A, García-Iglesias T, Sánchez-Hernández PE, Ramos-Solano M, Machado-Sulbaran AC. The Impact of the Reducing Agent on the Cytotoxicity and Selectivity Index of Silver Nanoparticles in Leukemia and Healthy Cells. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241858

Chicago/Turabian StyleAguirre-León, Jovani Guadalupe, Belkis Sulbarán-Rangel, Edsaúl Emilio Pérez-Guerrero, Antonio Topete-Camacho, Trinidad García-Iglesias, Pedro Ernesto Sánchez-Hernández, Moisés Ramos-Solano, and Andrea Carolina Machado-Sulbaran. 2025. "The Impact of the Reducing Agent on the Cytotoxicity and Selectivity Index of Silver Nanoparticles in Leukemia and Healthy Cells" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241858

APA StyleAguirre-León, J. G., Sulbarán-Rangel, B., Pérez-Guerrero, E. E., Topete-Camacho, A., García-Iglesias, T., Sánchez-Hernández, P. E., Ramos-Solano, M., & Machado-Sulbaran, A. C. (2025). The Impact of the Reducing Agent on the Cytotoxicity and Selectivity Index of Silver Nanoparticles in Leukemia and Healthy Cells. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1858. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241858