Carbon Dot-Modified Quercetin Enables Synergistic Enhancement of Charge Transfer and Oxygen Adsorption for Efficient H2O2 Photoproduction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Synthesis of CDs

2.2. Synthesis of QCDs and Quer

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Characterization and Photoelectric Properties of QCDs and Quer

3.2. The Photocatalytic Performance of QCDs and Quer

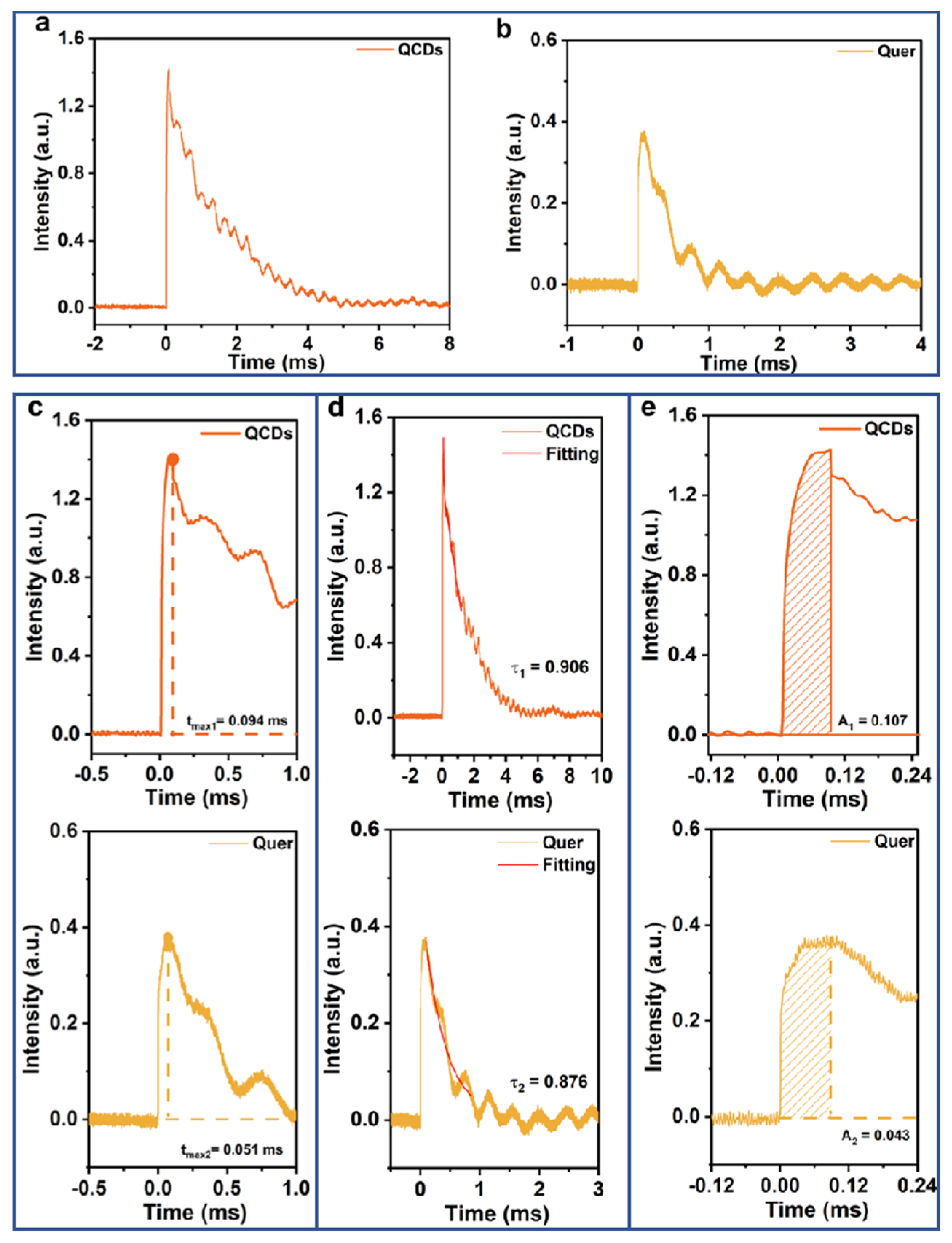

3.3. Dynamics of Electron Distribution at Catalytic Interfaces Tested by TPS

3.4. Electron Transfer Pathways Analyzed Using TPC

3.5. The Interfacial Charge Transfer Kinetics of Samples Tested by TPV

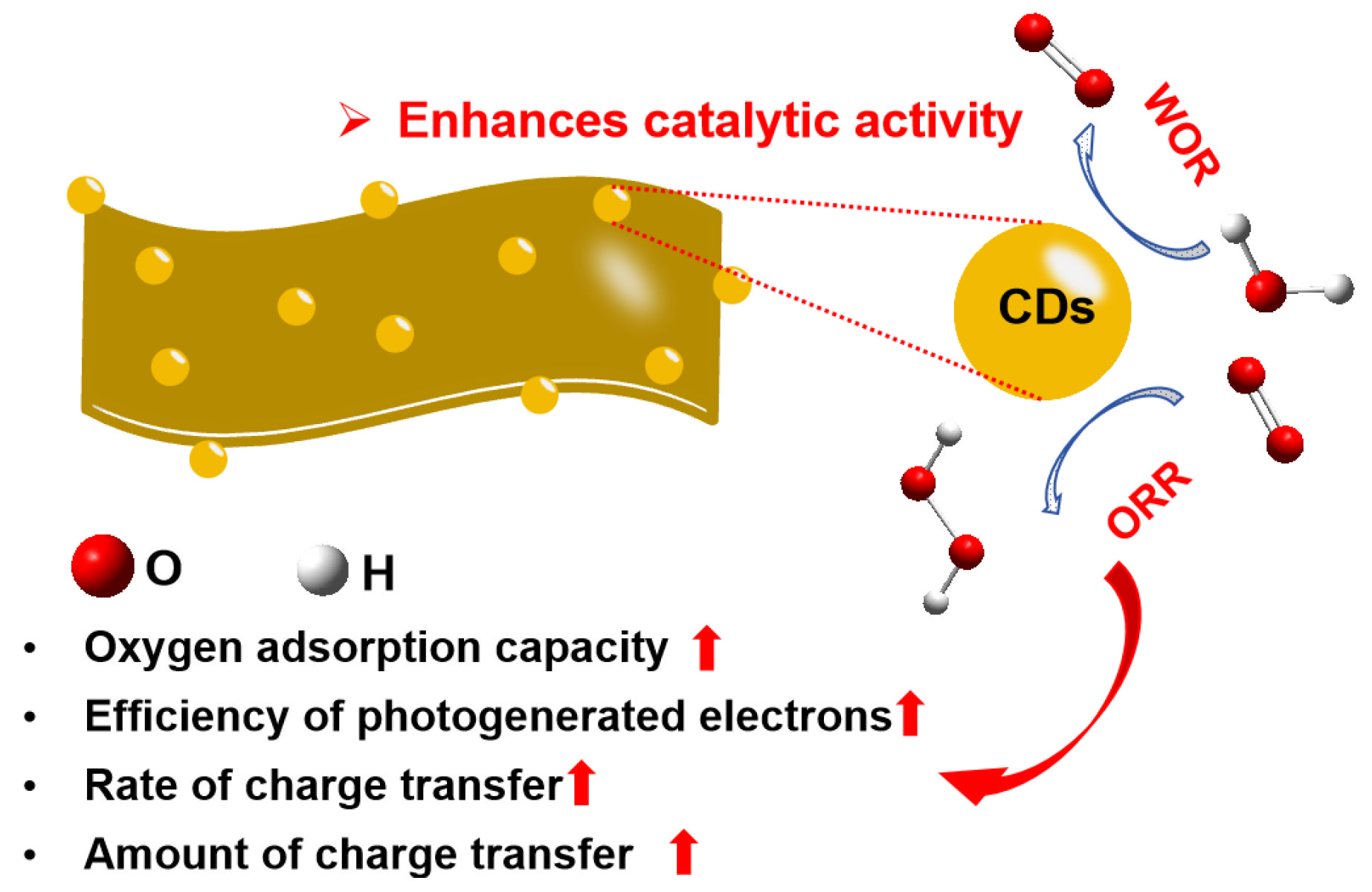

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xia, C.; Xia, Y.; Zhu, P.; Fan, L.; Wang, H. Direct electrosynthesis of pure aqueous H2O2 solutions up to 20% by weight using a solid electrolyte. Science 2019, 366, 226–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melchionna, M.; Fornasiero, P.; Prato, M. The rise of hydrogen peroxide as the main product by metal-free catalysis in oxygen reductions. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1802920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellinger, T.-P.; Hasché, F.; Strasser, P.; Antonietti, M. Mesoporous nitrogen-doped carbon for the electrocatalytic synthesis of hydrogen peroxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 4072–4075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freakley, S.J.; He, Q.; Harrhy, J.H.; Lu, L.; Crole, D.A.; Morgan, D.J.; Ntainjua, E.N.; Edwards, J.K.; Carley, A.F.; Borisevich, A.Y.; et al. Palladium-tin catalysts for the direct synthesis of H2O2 with high selectivity. Science 2016, 351, 965–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suk, M.; Chung, M.W.; Han, M.H.; Oh, H.-S.; Choi, C.H. Selective H2O2 production on surface-oxidized metal-nitrogen-carbon electrocatalysts. Catal. Today 2021, 359, 99–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, K.; Zhao, J.; Wang, H. Catalyst design for electrochemical oxygen reduction toward hydrogen peroxide. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2003321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Chen, L.; Wang, D.; Zhou, H.; Zhou, L.; Zhu, X.; Jiang, L.; Feng, X. Oxygen-tolerant hydrogen peroxide reduction catalysts for reliable noninvasive bioassays. Small 2019, 15, 1903320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraishi, Y.; Kanazawa, S.; Kofuji, Y.; Sakamoto, H.; Ichikawa, S.; Tanaka, S.; Hirai, T. Sunlight-driven hydrogen peroxide production from water and molecular oxygen by metal-free photocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 13454–13459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, B.; Xie, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Sheng, H.; Zhao, J. Proton reservoirs in polymer photocatalysts for superior H2O2 photosynthesis. Energy Environ. Sci. 2023, 16, 4612–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, X.; Huang, X.; Hu, Q.; Li, B.; Hu, C.; Ma, B.; Ding, Y. Recent developments in photocatalytic production of hydrogen peroxide. Chem. Commun. 2024, 60, 5354–5368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limpachanangkul, P.; Liu, L.; Hunsom, M.; Chalermsinsuwan, B. Low energy photocatalytic glycerol conversion to high valuable products via Bi2O3 polymorphs in the presence of H2O2. Energy Rep. 2020, 6, 95–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, W.; Dong, F.; Zhang, Z.; Han, L.; Luo, X.; Huang, J.; Feng, Z.; Chen, Z.; Jia, G.; et al. Recent advances in noncontact external-field-assisted photocatalysis: From fundamentals to applications. ACS Catal. 2021, 11, 4739–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, P.; Panda, P.K.; Su, C.; Lin, Y.C.; Sakthivel, R.; Chen, S.L.; Chung, R.J. Near-infrared-driven upconversion nanoparticles with photocatalysts through water-splitting towards cancer treatment. J. Mater. Chem. B 2024, 12, 3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, P.S.M.; Lee, D.Y.; Cho, H.; Son, S.H.; Jae, J.; Kim, J.R.; Kwon, O.S.; Haider, Z.; Kim, H.I. Biomass-Derived Carbon for Solar H2O2 Production: Current Trends and Future Directions. Mater. Today Energy 2025, 47, 101840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, A.; Kumar, P.S.; Jeevanantham, S.; Anubha, M.; Jayashree, S. Degradation of toxic agrochemicals and pharmaceutical pollutants: Effective and alternative approaches toward photocatalysis. Environ. Pollut. 2022, 298, 118844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zou, Y.; Jin, B.; Zhang, K.; Park, J.H. Hydrogen peroxide production from solar water oxidation. ACS Energy Lett. 2019, 4, 3018–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Jena, H.S.; Feng, X.; Leus, K.; Van Der Voort, P. Engineering covalent organic frameworks as heterogeneous photocatalysts for organic transformations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202204938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasija, V.; Nguyen, V.-H.; Kumar, A.; Raizada, P.; Krishnan, V.; Khan, A.A.P.; Singh, P.; Lichtfouse, E.; Wang, C.; Thi Huong, P. Advanced activation of persulfate by polymeric g-C3N4 based photocatalysts for environmental remediation: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 413, 125324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Minh, T.; Song, J.; Deb, A.; Cha, L.; Srivastava, V.; Sillanpää, M. Biochar based catalysts for the abatement of emerging pollutants: A review. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 394, 124856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zeng, Q.; Tao, S.; Xia, C.; Liu, C.; Liu, P.; Yang, B. Carbon dots based photoinduced reactions: Advances and perspective. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2207621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.-L.; Chen, L.; Gao, L.-J.; Ren, J.-T.; Yuan, Z.-Y. Engineering g-C3N4 based materials for advanced photocatalysis: Recent advances. Green Energy Environ. 2024, 9, 166–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, A.; Sun, Y.; Gao, Z.; Yang, S.; Liu, Y.; He, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, S. Internal electric field in carbon nitride-based heterojunctions for photocatalysis. Nano Energy 2023, 108, 108228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savateev, A.; Ghosh, I.; König, B.; Antonietti, M. Photoredox catalytic organic transformations using heterogeneous carbon nitrides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 57, 15936–15947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, J.; Tian, W.; Guan, Z.; Zhang, H.; Duan, X.; Wang, H.; Sun, H.; Fang, Y.; Huang, Y.; Wang, S. Functional carbon nitride materials in photo-fenton-like catalysis for environmental remediation. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2201743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Han, L.; Strasser, P. A comparative perspective of electrochemical and photochemical approaches for catalytic H2O2 production. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6605–6631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ballesteros, N.; Martins, P.M.; Tavares, C.J.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Quercetin-mediated green synthesis of Au/TiO2 nanocomposites for the photocatalytic degradation of antibiotic ciprofloxacin. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2025, 143, 526–537. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F.-Y.; Zhang, H.-X.; Ma, S.-H.; Kong, D.-M.; Hao, P.-P.; Zhu, L.-N. Quercetin sensitized covalent organic framework for boosting photocatalytic H2O2 production and antibacterial. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 693, 137593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, H.; Garg, S.; Shukla, C.R.; Upadhyay, S.; Rohilla, J.; Szamosvölgyi, Á.; Efremova, A.; Szenti, I.; Sapi, A.; Ingole, P.P.; et al. Efficient visible light driven photocatalysis using BiOBr/BiOI heterojunction modified by quercetin and defect engineering via simple mechanical grinding: Experiments & first-principles analysis. Mater. Res. Bull. 2025, 184, 113268. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Wang, J.; He, T.; Li, Z.; Xu, H.; Fan, Z.; Liao, F.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z. Dynamic machine learning-driven optimization of microwave-synthesized photocatalysts for enhanced hydrogen peroxide production. ChemCatChem 2025, 17, e00341. [Google Scholar]

- Han, M.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Bai, L.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, H.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z. High-bright fluorescent carbon dot as versatile sensing platform. Talanta 2017, 174, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, M.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Y.; Zhu, C.; Hu, L.; Gao, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z. Cobalt phosphide/carbon dots composite as an efficient electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction. Dalton Trans. 2018, 47, 5459–5464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Zhao, S.; Wu, X.; Li, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, C.; Yang, N.; Jiang, X.; Gao, J.; Bai, L.; et al. A Co3O4-CDots-C3N4 three component electrocatalyst design concept for efficient and tunable CO2 reduction to syngas. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, C.; Liu, C.; Fu, Y.; Gao, J.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z. Construction of CDs/CdS photocatalysts for stable and efficient hydrogen production in water and seawater. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 242, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamila, G.S.; Sajjad, S.; Leghari, S.A.K.; Long, M. Nitrogen doped carbon quantum dots and GO modified WO3 nanosheets combination as an effective visible photo catalyst. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 382, 121087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Guan, D.; Gu, Y.; Xu, H.; Wang, C.; Shao, Z.; Guo, Y. Tuning Synergy Between Nickel and Iron in Ruddlesden–Popper Perovskites Through Controllable Crystal Dimensionalities Towards Enhanced Oxygen-Evolving Activity and Stability. Carbon Energy 2024, 6, e465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; et al. A comprehensive understanding on the roles of carbon dots in metallated graphyne based catalyst for photoinduced H2O2 production. Nano Today 2022, 43, 101428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, J.; Si, H.; Wu, Y.; Guo, Z.; Wang, X.; Liao, F.; Huang, H.; et al. In-situ study of the hydrogen peroxide photoproduction in seawater on carbon dot-based metal-free catalyst under operation condition. Nano Res. 2024, 17, 5956–5964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Deng, Y.; Shen, M.; Ye, Y.-X.; Zhu, F.; Yang, X.; Ouyang, G. Regulation the reactive oxygen species on conjugated polymers for highly efficient photocatalysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2022, 314, 121488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Li, J.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Yuan, W.; Zhang, T.; Shen, J.; Ma, Y.; Fan, Z.; Liao, F.; et al. Operando interfacial kinetic study of H2O2 photoproduction over carbon dots stabilized gold nanoclusters. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 2025, 361, 124679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wu, Q.; Nie, H.; Si, H.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Shao, M.; Kang, Z. Highly efficient metal-free catalyst from cellulose for hydrogen peroxide photoproduction instructed by machine learning and transient photovoltage technology. Nano Res. 2022, 15, 4000–4007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Dong, B.; Shao, M.; Kang, Z. Polyaniline/carbon dots composite as a highly efficient metal-free dual-functional photoassisted electrocatalyst for overall water splitting. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 24814–24823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Shi, X.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X.; Shao, M.; Huang, H.; et al. Carbon nitride assisted 2D conductive metal-organic frameworks composite photocatalyst for efficient visible light-driven H2O2 production. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 289, 120035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Zhao, Y.; Zong, X.; Nie, H.; Niu, L.; An, L.; Qu, D.; Wang, X.; Kang, Z.; Sun, Z. Photocatalyst for high-performance h2 production: Ga-doped polymeric carbon nitride. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6124–6129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Guo, H.; Qi, X. Recent Advances in Metal Sulfide-Based Photocatalysts for Biomass-Based Hydroxyl Compounds Valorization. J. Energy Chem. 2025, 109, 24–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Duan, X.; Wei, W.; Wang, S.; Ni, B.-J. Photocatalytic conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to valuable products. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 4266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Luo, N.; Xie, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y. Photocatalytic transformations of lignocellulosic biomass into chemicals. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 6198–6223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.; Li, D.; Yuan, S.; Chen, Z. Recent advances in biomass-based photocatalytic H2 production and efficient photocatalysts: A Review. Energy Fuels 2022, 36, 10721–10731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, C.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Song, Y.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y.; Kang, Z. Photocatalytic H2O2 and H2 generation from living chlorella vulgaris and carbon micro particle comodified g-C3N4. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1802525. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, J.; Chen, B.; Lv, W.; Zhou, L.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. Robust photocatalytic H2O2 Production over Inverse Opal g-C3N4 with carbon vacancy under visible light. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 16467–16473. [Google Scholar]

- Kofuji, Y.; Ohkita, S.; Shiraishi, Y.; Sakamoto, H.; Tanaka, S.; Ichikawa, S.; Hirai, T. Graphitic carbon nitride doped with biphenyl diimide: Efficient photocatalyst for hydrogen peroxide production from water and molecular oxygen by sunlight. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7021–7029. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, D.-L.; Haider, Z.; Krishnan, K.; Kanagaraj, T.; Son, S.H.; Jae, J.; Kim, J.R.; Kumar, P.S.M.; Kim, H. Oxygen-enriched carbon quantum dots from coffee waste: Extremely active organic photocatalyst for sustainable solar-to-H2O2 conversion. Chemosphere 2024, 361, 142330. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, H.; Li, Z.; Wang, J.; Liao, F.; Huang, H.; Liu, Y. Carbon Dot-Modified Quercetin Enables Synergistic Enhancement of Charge Transfer and Oxygen Adsorption for Efficient H2O2 Photoproduction. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241856

Xu H, Li Z, Wang J, Liao F, Huang H, Liu Y. Carbon Dot-Modified Quercetin Enables Synergistic Enhancement of Charge Transfer and Oxygen Adsorption for Efficient H2O2 Photoproduction. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241856

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Haojie, Zenan Li, Jiaxuan Wang, Fan Liao, Hui Huang, and Yang Liu. 2025. "Carbon Dot-Modified Quercetin Enables Synergistic Enhancement of Charge Transfer and Oxygen Adsorption for Efficient H2O2 Photoproduction" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241856

APA StyleXu, H., Li, Z., Wang, J., Liao, F., Huang, H., & Liu, Y. (2025). Carbon Dot-Modified Quercetin Enables Synergistic Enhancement of Charge Transfer and Oxygen Adsorption for Efficient H2O2 Photoproduction. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1856. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241856