Effect of Incorporation of Mg on LiTa0.6Nb0.4O3 Photocatalytic Performance in Air-Cathode MFCs for Bioenergy Production and Wastewater Treatment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Catalysts Elaboration

2.2. Catalyst Characterization Methods

2.3. Air-Cathode MFC Configuration and Operation

2.4. COD Removal

2.5. Electrochemical Measurements

3. Results

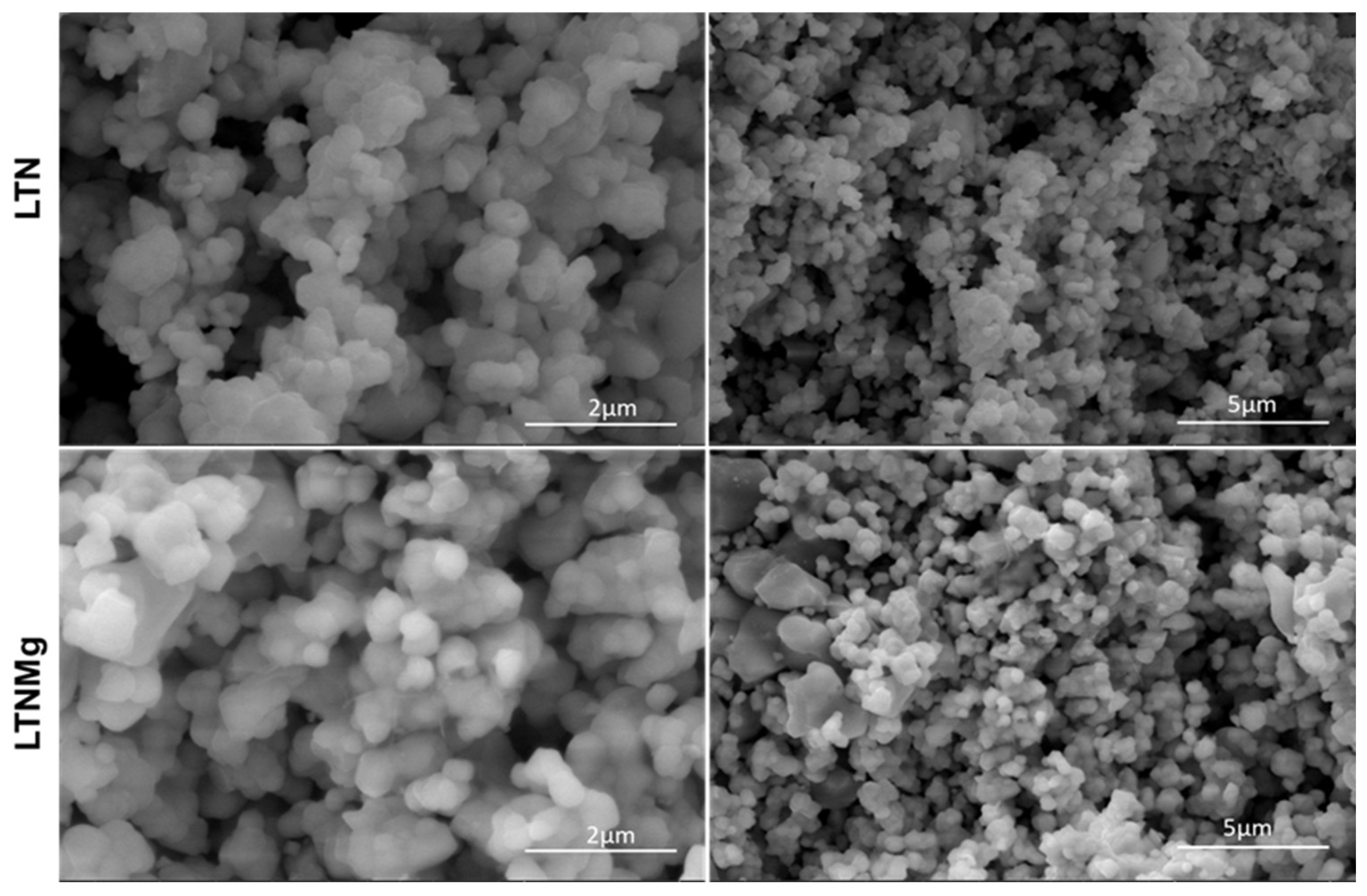

3.1. Catalyst Characterization

3.2. Electrochemical Performance

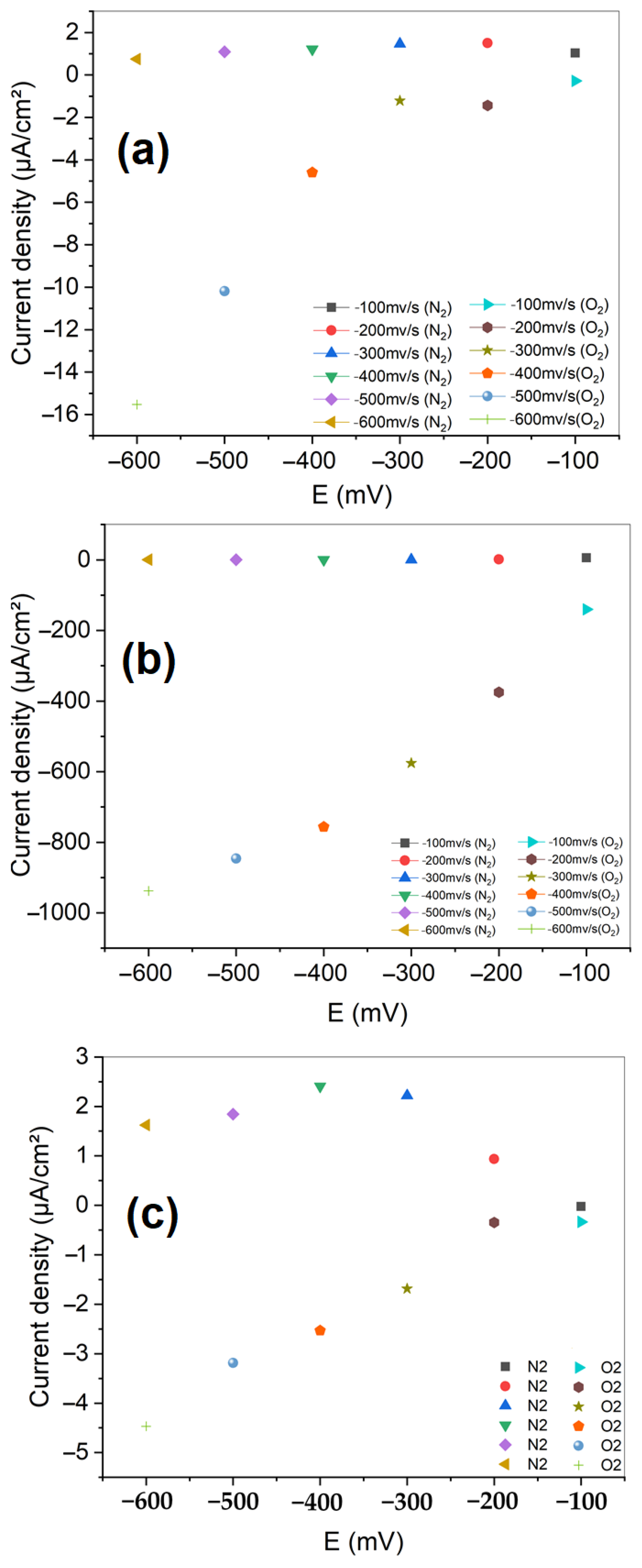

3.2.1. Cyclic Voltammetry

3.2.2. Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV)

3.2.3. Chronoamperometry

3.2.4. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy EIS

3.3. Catalysts Power Performance and Wastewater Treatment in Air-Cathode MFCs

3.3.1. Power Performance

3.3.2. Wastewater Treatment

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Papiya, F.; Nandy, A.; Mondal, S.; Kundu, P.P. Co/Al2O3-rGO Nanocomposite as Cathode Electrocatalyst for Superior Oxygen Reduction in Microbial Fuel Cell Applications: The Effect of Nanocomposite Composition. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 254, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Yan, L.; Li, K.; Ge, B.; Pu, L.; Zhang, X. The Performance and Mechanism of Modified Activated Carbon Air Cathode by Non-Stoichiometric Nano Fe3O4 in the Microbial Fuel Cell. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2015, 74, 989–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahani, F.S.; Mecheri, B.; Majidi, M.R.; de Oliveira, M.A.C.; D’Epifanio, A.; Zurlo, F.; Placidi, E.; Arciprete, F.; Licoccia, S. MnOx-Based Electrocatalysts for Enhanced Oxygen Reduction in Microbial Fuel Cell Air Cathodes. J. Power Sources 2018, 390, 45–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Hou, Y.; Abu-Reesh, I.M.; Chen, J.; He, Z. Oxygen Reduction Reaction Catalysts Used in Microbial Fuel Cells for Energy-Efficient Wastewater Treatment: A Review. Mater. Horiz. 2016, 3, 382–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papiya, F.; Pattanayak, P.; Kumar, P.; Kumar, V.; Kundu, P.P. Development of Highly Efficient Bimetallic Nanocomposite Cathode Catalyst, Composed of Ni:Co Supported Sulfonated Polyaniline for Application in Microbial Fuel Cells. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 282, 931–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peera, S.G.; Maiyalagan, T.; Liu, C.; Ashmath, S.; Lee, T.G.; Jiang, Z.; Mao, S. A Review on Carbon and Non-Precious Metal Based Cathode Catalysts in Microbial Fuel Cells. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2021, 46, 3056–3089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Chakraborty, I.; Rajesh, P.P.; Ghangrekar, M.M. Performance Evaluation of Microbial Fuel Cell Operated with Pd or MnO2 as Cathode Catalyst and Chaetoceros Pretreated Anodic Inoculum. J. Hazard. Toxic Radioact. Waste 2020, 24, 04020009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyadarshini, M.; Ahmad, A.; Das, S.; Ghangrekar, M.M. Metal Organic Frameworks as Emergent Oxygen-Reducing Cathode Catalysts for Microbial Fuel Cells: A Review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 19, 11539–11560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ray, S.K.; Cho, J.; Hur, J. A Critical Review on Strategies for Improving Efficiency of BaTiO3-Based Photocatalysts for Wastewater Treatment. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 290, 112679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Zhang, Y.; Park, S.-J. Recent Advances in Carbonaceous Photocatalysts with Enhanced Photocatalytic Performances: A Mini Review. Materials 2019, 12, 1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, S.; Manickam, M.; Sivasubramanian, R. A Sol–Gel Derived LaCoO3 Perovskite as an Electrocatalyst for Al–Air Batteries. Dalton Trans. 2024, 53, 3713–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nano Hexagon NiCeO2 for Al–Air Batteries: A Combined Experimental and Density Functional Theory Study of Oxygen Reduction Reaction Activity—Murdoch University. Available online: https://researchportal.murdoch.edu.au/esploro/outputs/journalArticle/Nano-Hexagon-NiCeO2-for-AlAir-Batteries/991005818348207891 (accessed on 26 November 2025).

- Han, N.; Race, M.; Zhang, W.; Marotta, R.; Zhang, C.; Bokhari, A.; Klemes, J.J. Perovskite and Related Oxide Based Electrodes for Water Splitting. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 318, 128544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, N.; Shen, Z.; Zhao, X.; Chen, R.; Thakur, V.K. Perovskite Oxides for Oxygen Transport: Chemistry and Material Horizons. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, F.; Mohsennia, M.; Pazouki, M. Highly Efficient Cathode for the Microbial Fuel Cell Using LaXO3 (X = [Co, Mn, Co0.5Mn0.5]) Perovskite Nanoparticles as Electrocatalysts. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbazi Farahani, F.; Mecheri, B.; Majidi, M.R.; Placidi, E.; D’Epifanio, A. Carbon-Supported Fe/Mn-Based Perovskite-Type Oxides Boost Oxygen Reduction in Bioelectrochemical Systems. Carbon 2019, 145, 716–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, G.; Sharma, M.; Bowen, C.; Vaish, R. 12-Ferroelectric Ceramics and Glass Ceramics for Photocatalysis. In Ceramic Science and Engineering; Misra, K.P., Misra, R.D.K., Eds.; Elsevier Series on Advanced Ceramic Materials; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2022; pp. 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djellabi, R.; Ordonez, M.F.; Conte, F.; Falletta, E.; Bianchi, C.L.; Rossetti, I. A Review of Advances in Multifunctional XTiO3 Perovskite-Type Oxides as Piezo-Photocatalysts for Environmental Remediation and Energy Production. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 421, 126792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitar, M.E.H.; Benzaouak, A.; Touach, N.-E.; Kharti, H.; Assani, A.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M. Sustainable Electricity Generation Using LiTaO3-Modified Mn2+ Ferroelectric Photocathode in Microbial Fuel Cells: Structural Insights and Enhanced Waste Bioconversion. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2024, 837, 141055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louki, S.; Touach, N.; Benzaouak, A.; Salar-García, M.J.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Hernández-Fernández, F.J.; de Los Ríos, A.P.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M. Preparation of New Ferroelectric Li0.95Ta0.57Nb0.38Cu0.15O3 Materials as Photocatalysts in Microbial Fuel Cells. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 96, 1656–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalan, V.; Mitchell, T.E.; Furukawa, Y.; Kitamura, K. The Role of Nonstoichiometry in 180° Domain Switching of LiNbO3 Crystals. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1998, 72, 1981–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, M.; Dunn, S. Influence of the Ferroelectric Nature of Lithium Niobate to Drive Photocatalytic Dye Decolorization under Artificial Solar Light. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 20854–20859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Dai, L.; Yuan, Y.; Yuan, H. Up-Conversion Luminescence and Defect Structures in Sc: Dy: LiNbO3 Crystals Affected by Sc3+ concentration. Opt. Mater. 2023, 143, 114196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, N.; Lampert, C.M. Electrochemical Lithium Insertion in Sol-Gel Deposited LiNbO3 Films. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 1995, 39, 367–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaouak, A.; Touach, N.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Salar-García, M.J.; Hernández-Fernández, F.J.; de Los Ríos, A.P.; Mahi, M.E.; Lotfi, E.M. Ferroelectric LiTaO3 as Novel Photo-Electrocatalyst in Microbial Fuel Cells. Environ. Prog. Progress. Sustain. Energy 2017, 36, 1568–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touach, N.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Salar-García, M.J.; Benzaouak, A.; Hernández-Fernández, F.; de Ríos, A.P.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M. On the Use of Ferroelectric Material LiNbO3 as Novel Photocatalyst in Wastewater-Fed Microbial Fuel Cells. Particuology 2017, 34, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazkad, D.; Lazar, N.; Benzaouak, A.; Moussadik, A.; El Habib Hitar, M.; Touach, N.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M. Photocatalytic Properties Insight of Sm-Doped LiNbO3 in Ferroelectric Li1−xNbSm1/3xO3 System. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaouak, A.; Touach, N.-E.; Ortiz-Martínez, V.M.; Salar-García, M.J.; Hernández-Fernández, F.; de Los Ríos, A.P.; Mahi, M.E.; Lotfi, E.M. Ferroelectric Solid Solution Li1−xTa1−xWxO3 as Potential Photocatalysts in Microbial Fuel Cells: Effect of the W Content. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 2018, 26, 1985–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touach, N.; Benzaouak, A.; Toyir, J.; El Hamidi, A.; El Mahi, M.; Lotfi, E.M.; Kacimi, M.; Liotta, L.F. Bioenergy Generation and Wastewater Purification with Li0.95Ta0.76Nb0.19Mg0.15O3 as New Air-Photocathode for MFCs. Catalysts 2022, 12, 1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, E.W.; Baird, R.B.; Eaton, A.D.; Clesceri, L.S. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Wastewater; American Public Health Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012; Volume 10. [Google Scholar]

- Kadivarian, M.; Dadkhah, A.A.; Nasr Esfahany, M. Oily Wastewater Treatment by a Continuous Flow Microbial Fuel Cell and Packages of Cells with Serial and Parallel Flow Connections. Bioelectrochemistry 2020, 134, 107535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajdid Khajeh, R.; Aber, S.; Zarei, M. Comparison of NiCo2O4, CoNiAl-LDH, and CoNiAl-LDH@NiCo2O4 Performances as ORR Catalysts in MFC Cathode. Renew. Energy 2020, 154, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.-S.; Wang, D.-B.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Liang, Y.; Xie, J. Cobalt Oxide/Nanocarbon Hybrid Materials as Alternative Cathode Catalyst for Oxygen Reduction in Microbial Fuel Cell. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2015, 40, 3868–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velvizhi, G.; Babu, P.S.; Mohanakrishna, G.; Srikanth, S.; Mohan, S.V. Evaluation of Voltage Sag-Regain Phases to Understand the Stability of Bioelectrochemical System: Electro-Kinetic Analysis. RSC Adv. 2012, 2, 1379–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evaluation of Voltazge Sag-Regain Phases to Understand the Stability of Bioelectrochemical System: Electro-Kinetic Analysis—RSC Advances (RSC Publishing). Available online: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2012/ra/c1ra00674f (accessed on 3 March 2025).

- Srikanth, S.; Pavani, T.; Sarma, P.N.; Venkata Mohan, S. Synergistic Interaction of Biocatalyst with Bio-Anode as a Function of Electrode Materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2011, 36, 2271–2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, K.P.; Woodard, T.L.; Franks, A.E.; Summers, Z.M.; Lovley, D.R. Microbial Electrosynthesis: Feeding Microbes Electricity To Convert Carbon Dioxide and Water to Multicarbon Extracellular Organic Compounds. mBio 2010, 1, 10.1128–mbio.00103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srikanth, S.; Venkata Mohan, S. Influence of Terminal Electron Acceptor Availability to the Anodic Oxidation on the Electrogenic Activity of Microbial Fuel Cell (MFC). Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 123, 480–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, S.; Calay, R.K. Experimental Study of Power Generation and COD Removal Efficiency by Air Cathode Microbial Fuel Cell Using Shewanella Baltica 20. Energies 2022, 15, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Provenance | COD | DO | Temperature | Conductivity | pH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urbain waste water | 864 mg/L | 6.04 | 25 °C | 1.99 mS | 7.72 |

| Solid Solution | Band Gap (eV) | COD Initial (mgL−1) | OCV (mV) | Maximum Power Density (mWm−2) | COD Removal (%) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li0.95Ta0.57Nb0.38Mg0.15O3 | 3.60 | 864 | 680 | 764 | 75 | Present study |

| Li0.95Ta0.76Nb0.19Mg0.15O3 | 4.03 | 471 | 460 | 228 | 95.7 | [29] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Allali, F.; Kara, K.; Elmazouzi, S.; Lazar, N.; Tajounte, L.; Touach, N.; Benzaouak, A.; Lotfi, E.M.; Lahmar, A.; Liotta, L.F. Effect of Incorporation of Mg on LiTa0.6Nb0.4O3 Photocatalytic Performance in Air-Cathode MFCs for Bioenergy Production and Wastewater Treatment. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241837

Allali F, Kara K, Elmazouzi S, Lazar N, Tajounte L, Touach N, Benzaouak A, Lotfi EM, Lahmar A, Liotta LF. Effect of Incorporation of Mg on LiTa0.6Nb0.4O3 Photocatalytic Performance in Air-Cathode MFCs for Bioenergy Production and Wastewater Treatment. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(24):1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241837

Chicago/Turabian StyleAllali, Fouzia, Kaoutar Kara, Siham Elmazouzi, Noureddine Lazar, Latifa Tajounte, Noureddine Touach, Abdellah Benzaouak, El Mostapha Lotfi, Abdelilah Lahmar, and Leonarda Francesca Liotta. 2025. "Effect of Incorporation of Mg on LiTa0.6Nb0.4O3 Photocatalytic Performance in Air-Cathode MFCs for Bioenergy Production and Wastewater Treatment" Nanomaterials 15, no. 24: 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241837

APA StyleAllali, F., Kara, K., Elmazouzi, S., Lazar, N., Tajounte, L., Touach, N., Benzaouak, A., Lotfi, E. M., Lahmar, A., & Liotta, L. F. (2025). Effect of Incorporation of Mg on LiTa0.6Nb0.4O3 Photocatalytic Performance in Air-Cathode MFCs for Bioenergy Production and Wastewater Treatment. Nanomaterials, 15(24), 1837. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15241837