Sensitive Detection of Paraquat in Water Using Triangular Silver Nanoplates as SERS Substrates for Sustainable Agriculture and Water Resource Management

Abstract

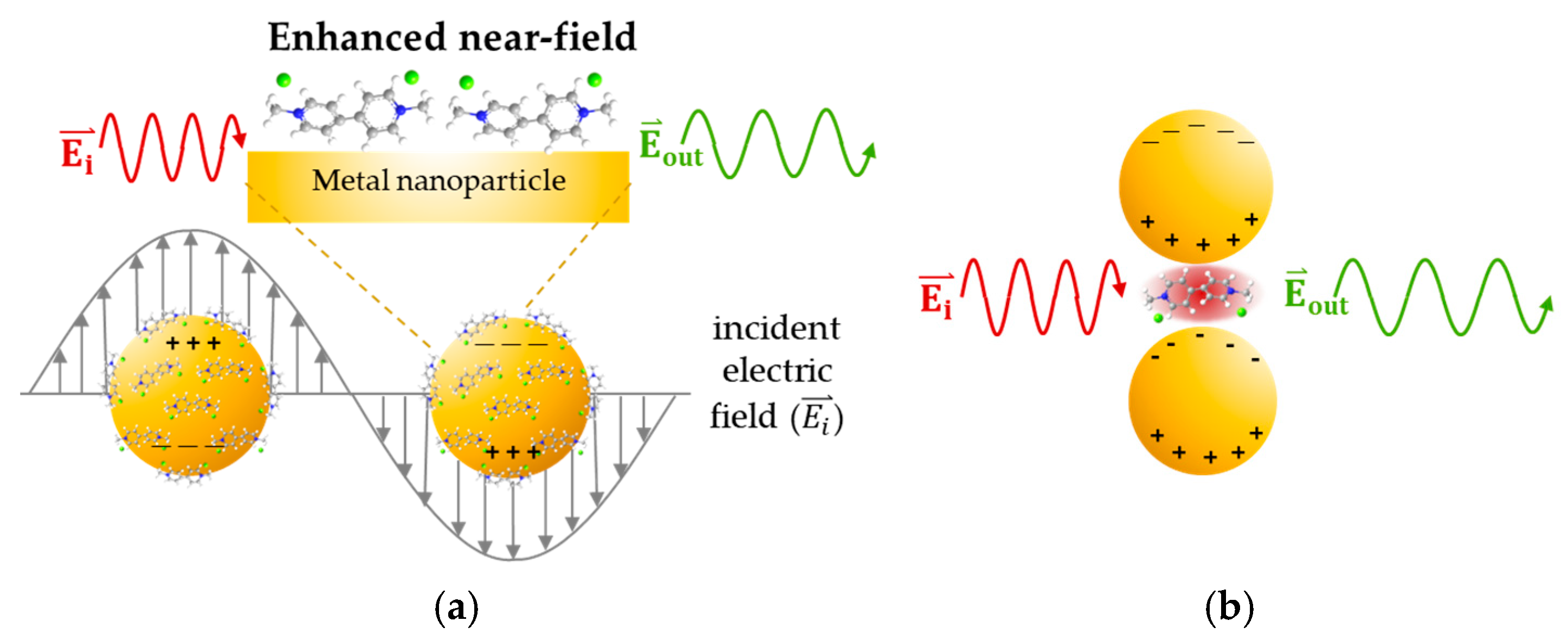

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

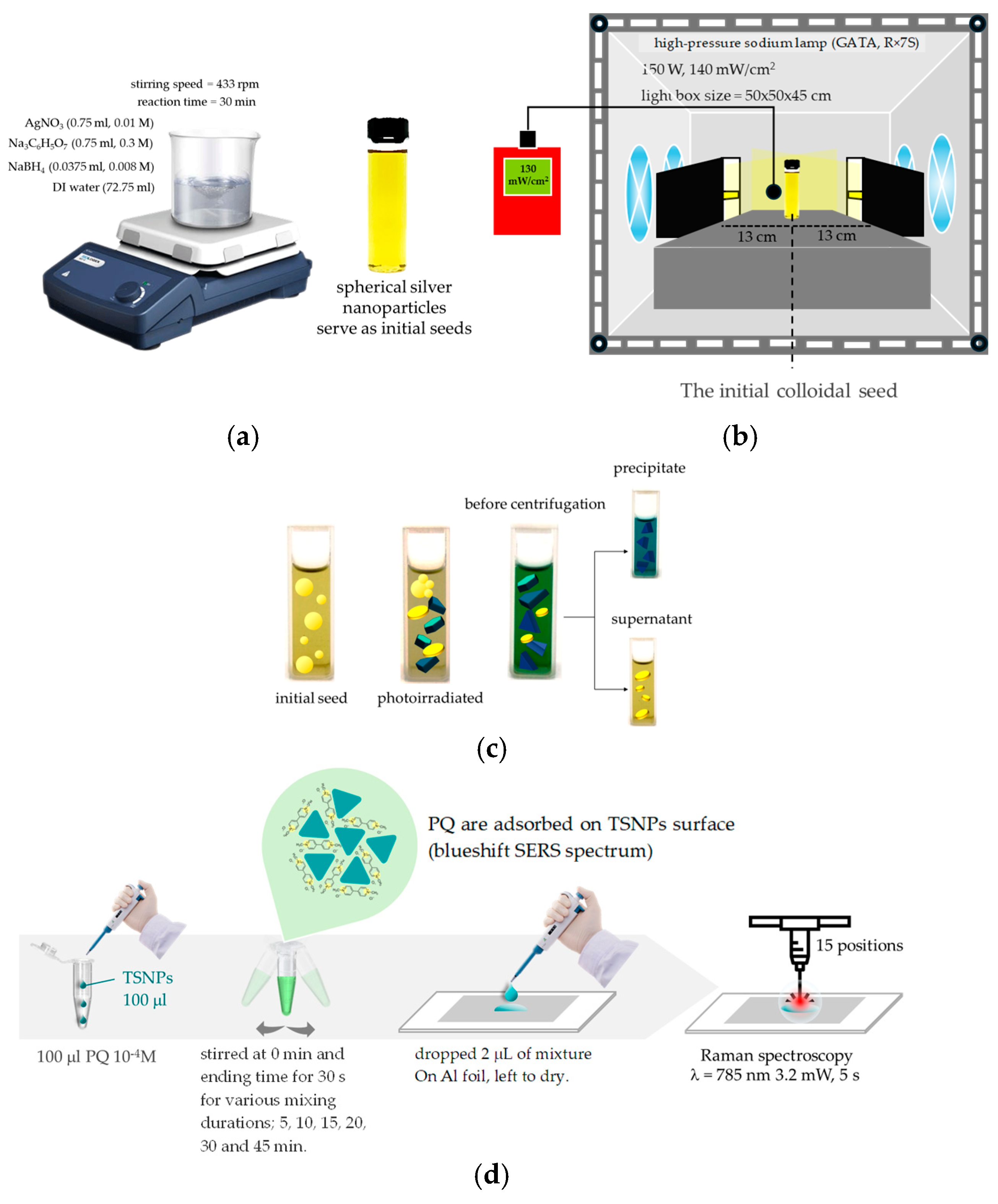

2.2. Synthesis of Triangular Silver Nanoplates (TSNPs)

2.3. Characterization of TSNPs

2.4. SERS Measurement of PQ

2.4.1. Preparation of Standard Solutions in Water Samples

2.4.2. Characteristics of Raman Spectrum of PQ

2.4.3. Optimizing the Mixing Time of TSNP Colloids with PQ Standard Solution

2.4.4. Performance of TSNP Colloidal SERS

2.5. Simulation and Application of TSNP Colloidal SERS for Environmental PQ Detection

3. Results

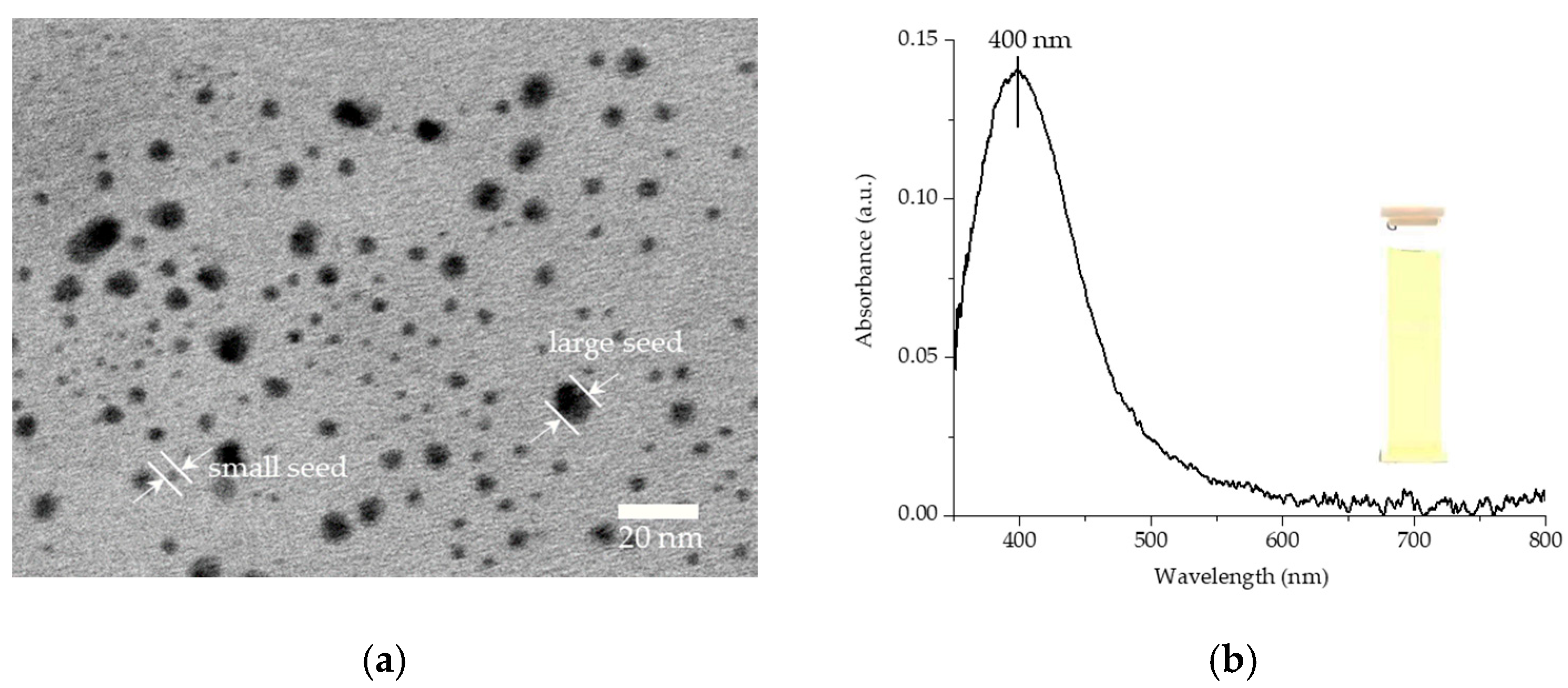

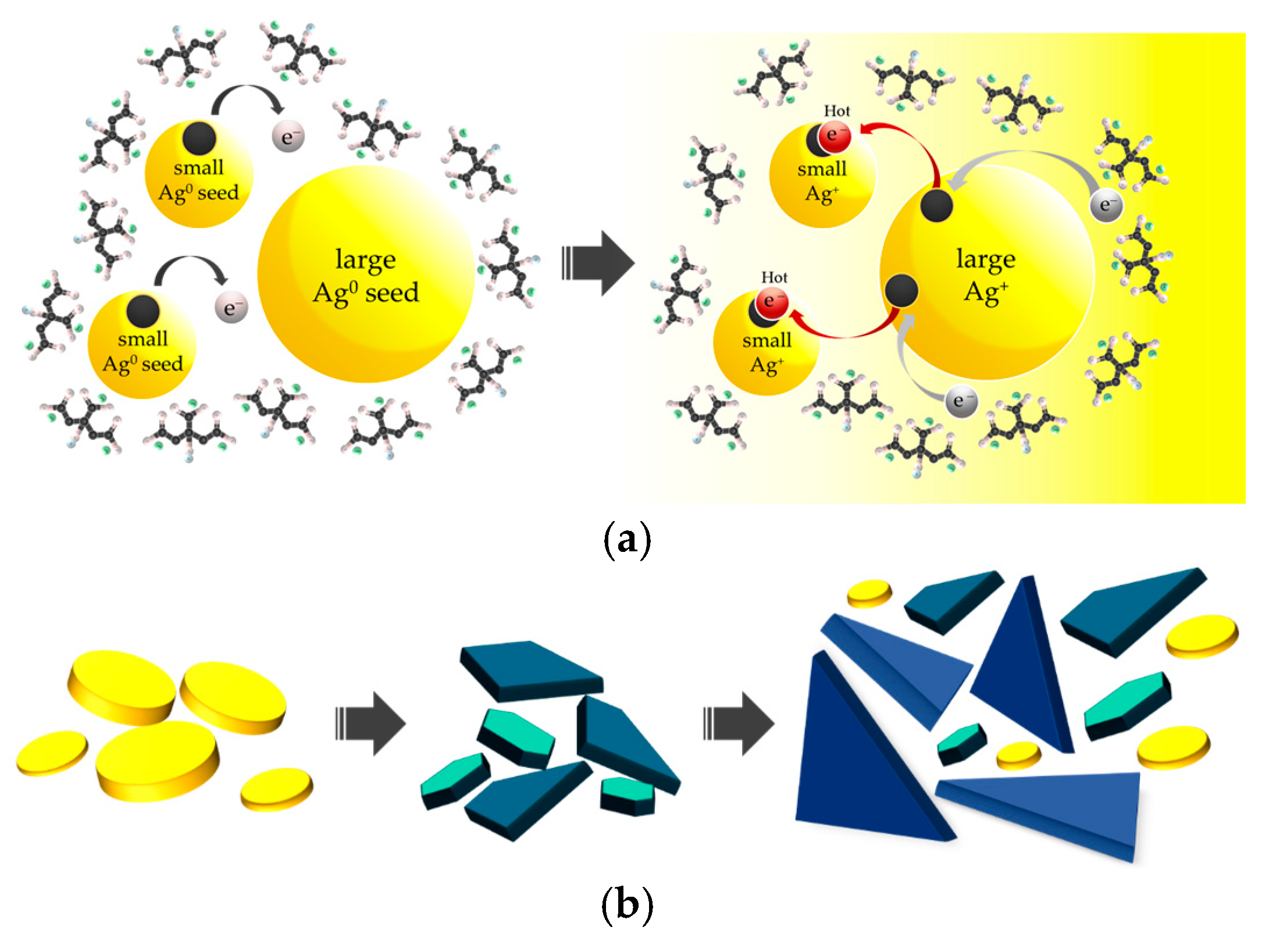

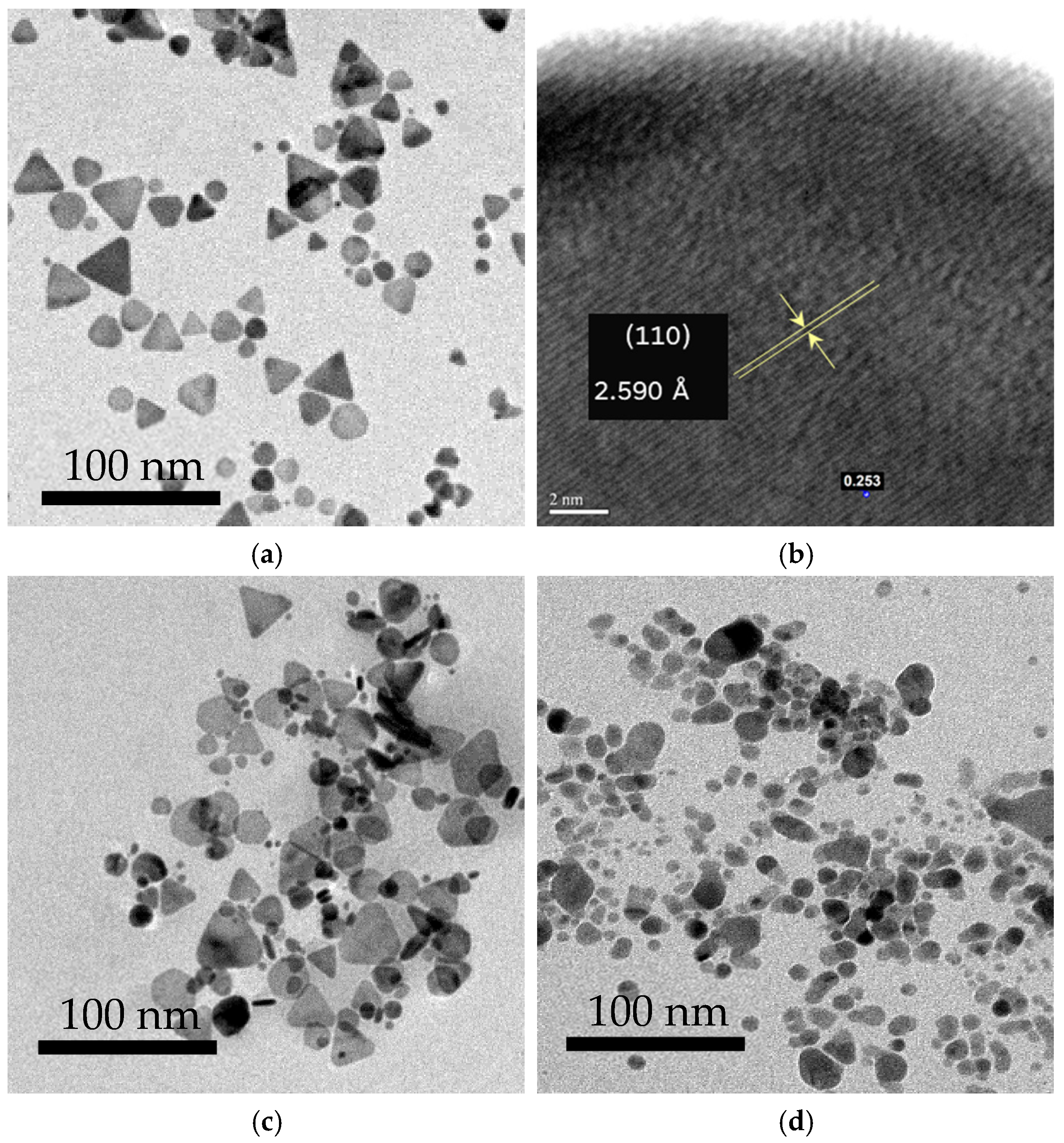

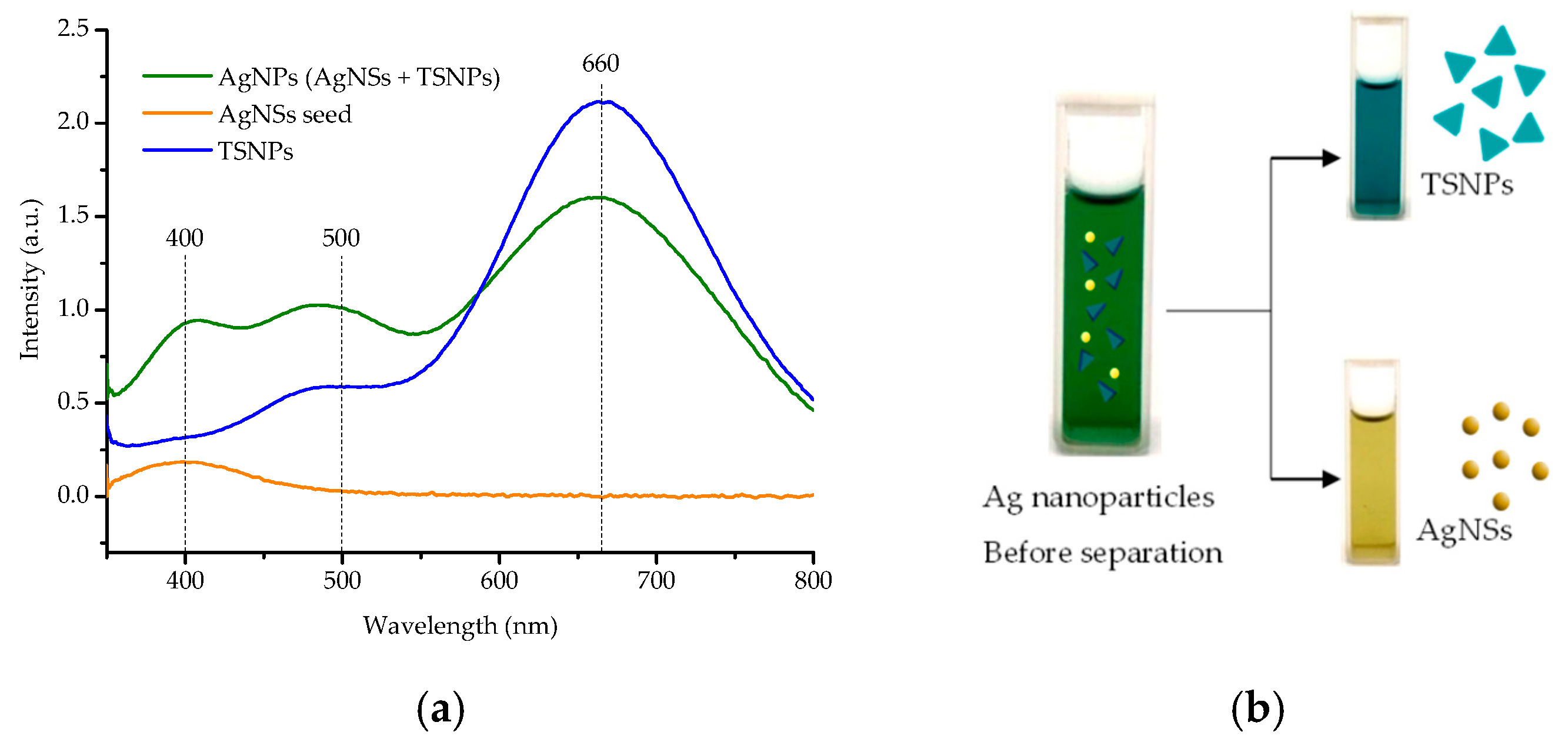

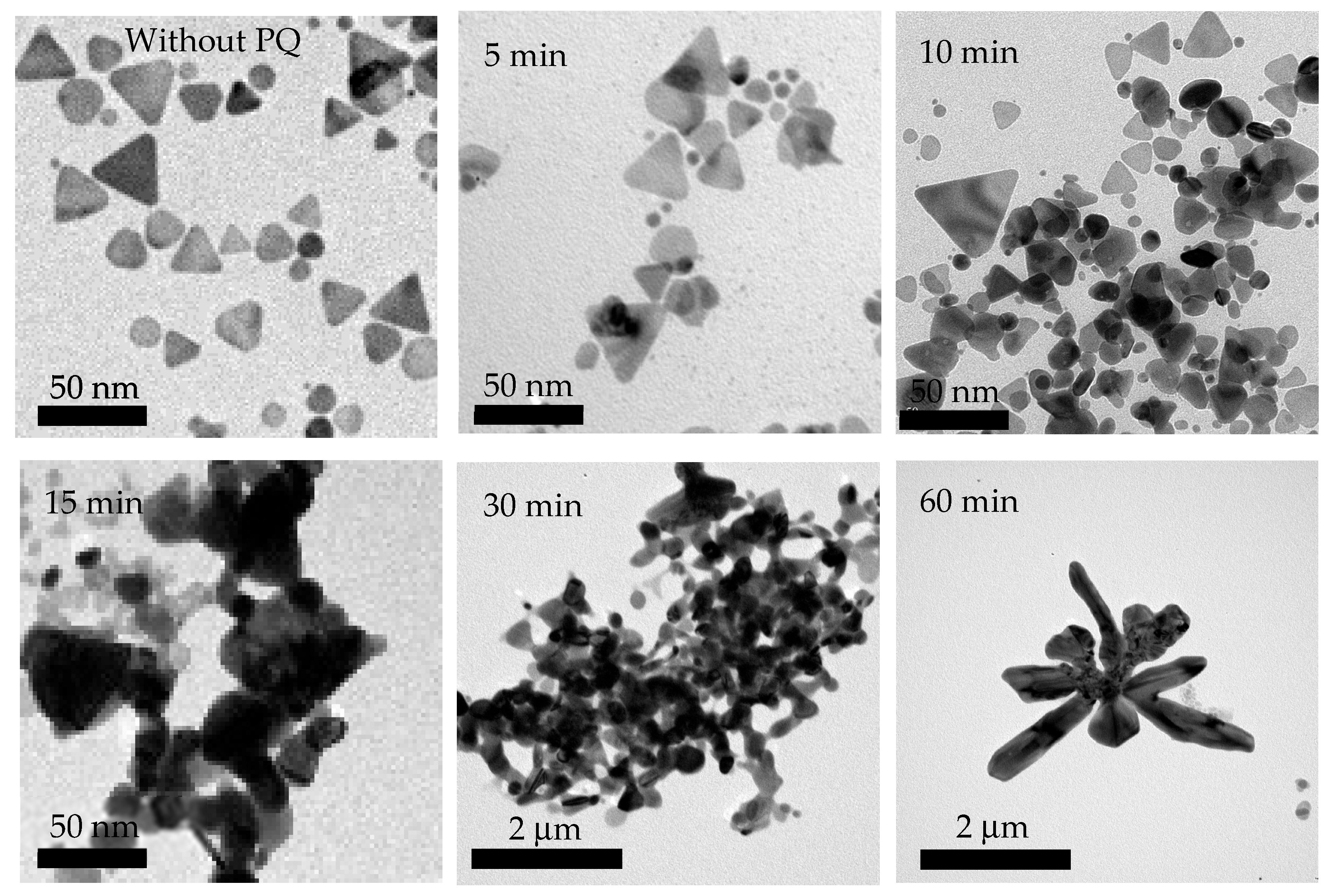

3.1. Structural Formation and Morphological Properties of TSNPs

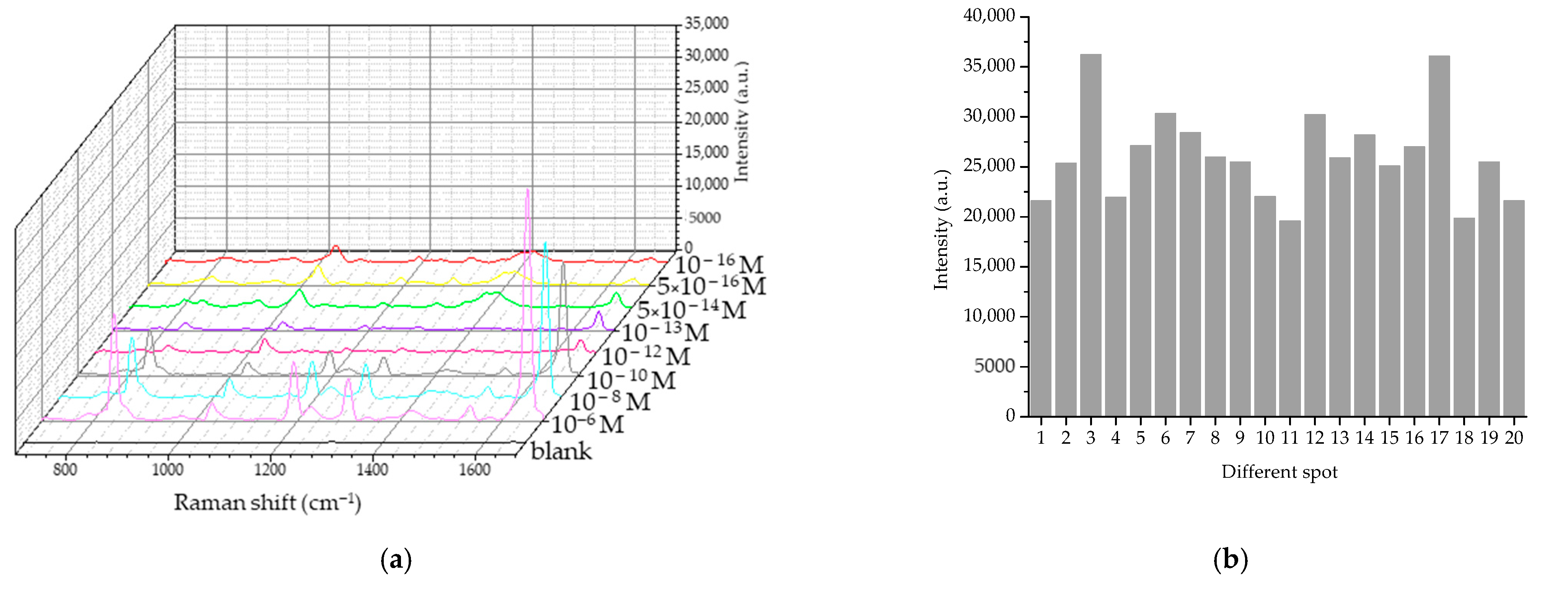

3.2. PQ Detection Using the TSNP Colloidal SERS

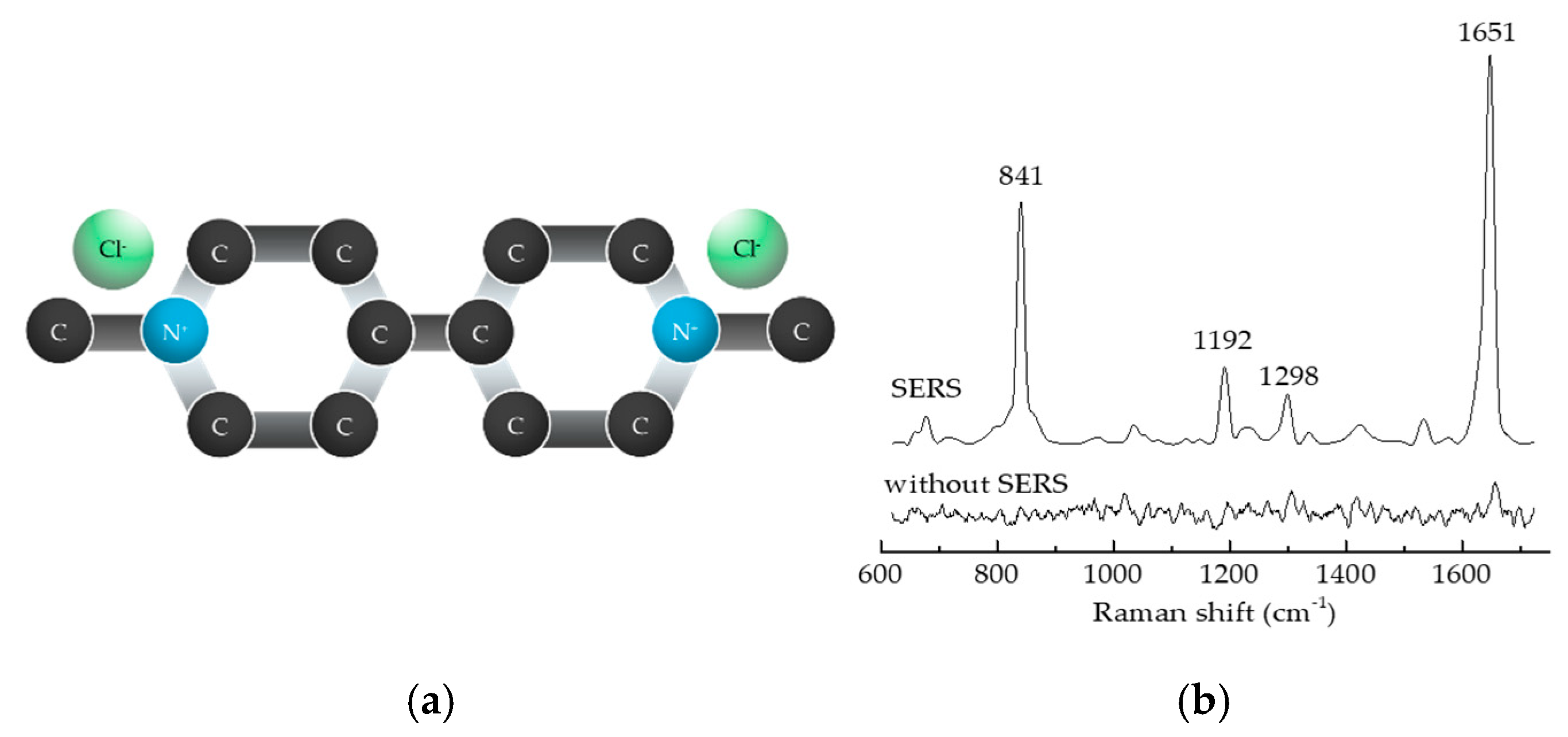

3.2.1. Characteristics of the Raman Signal of PQ

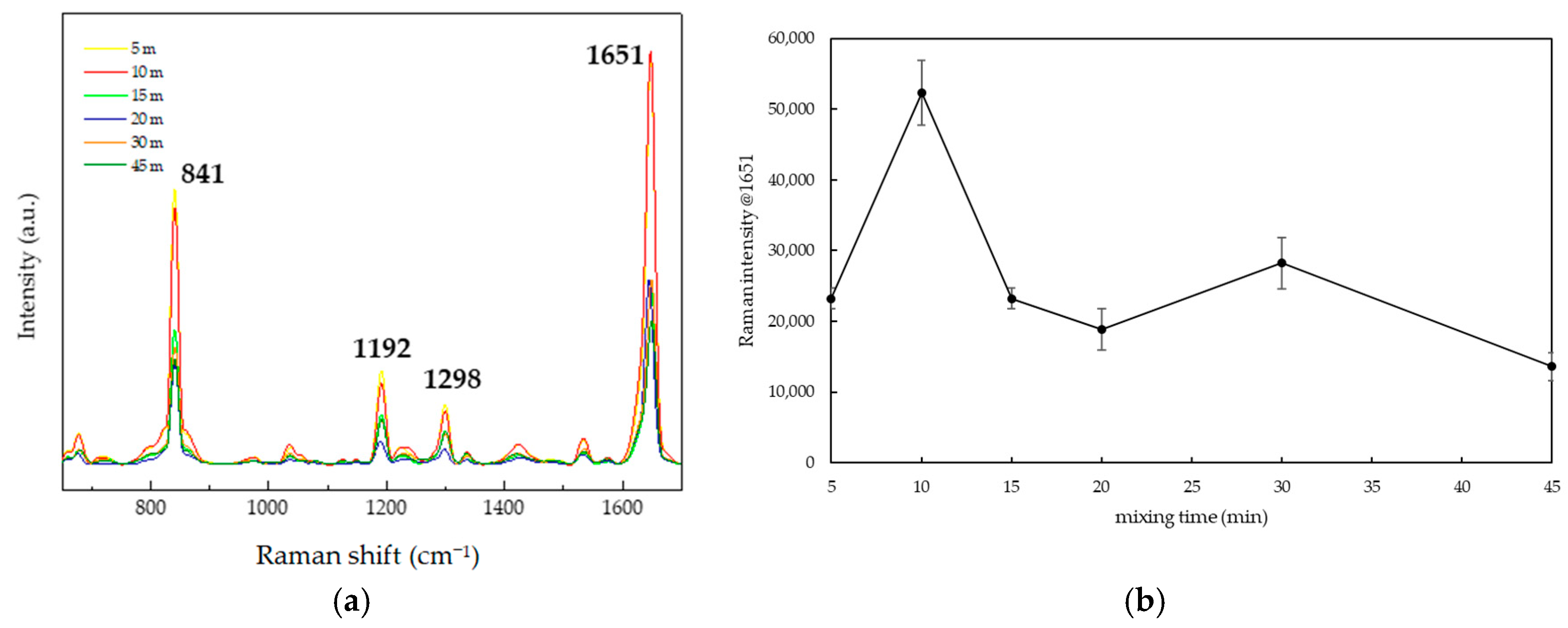

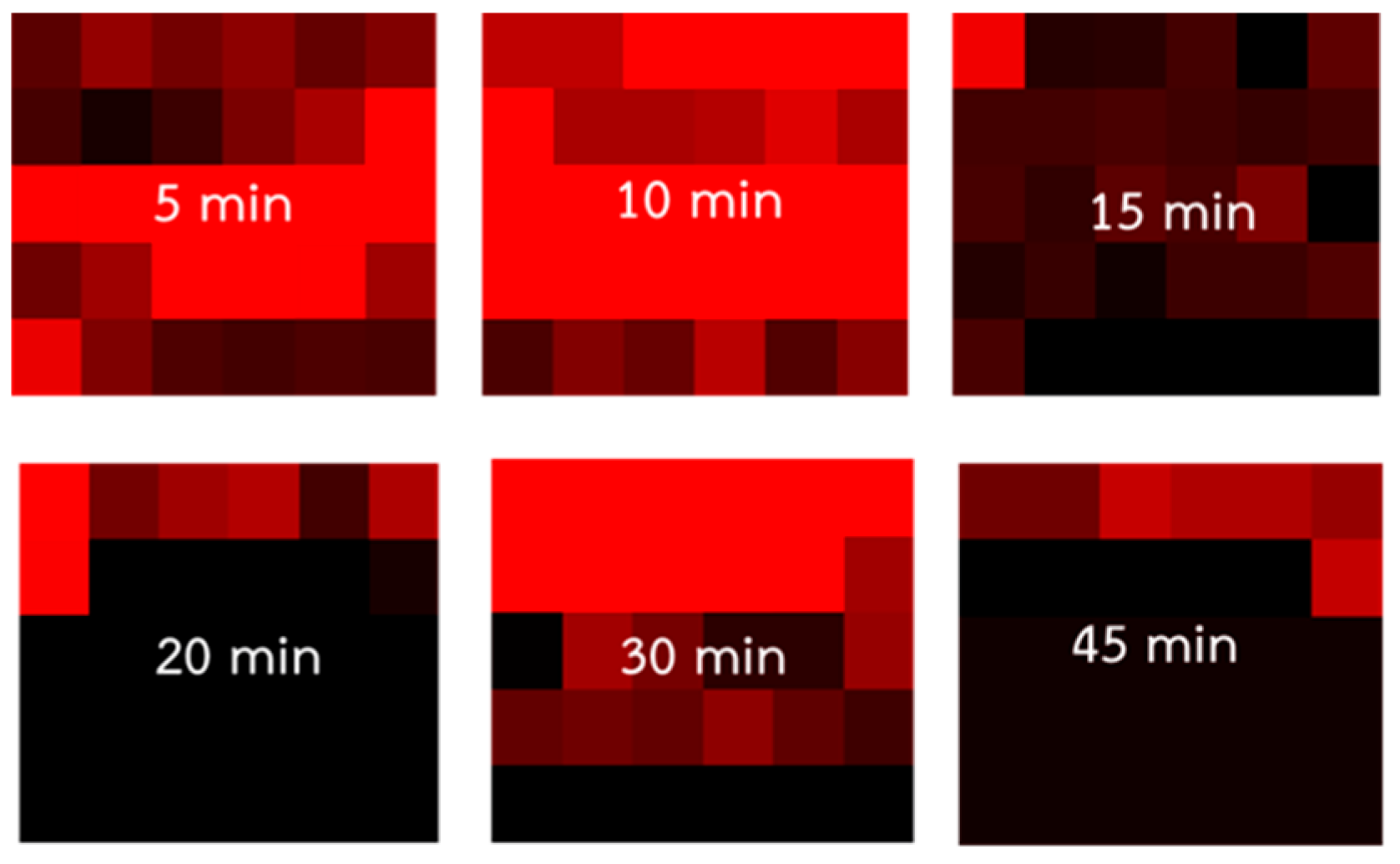

3.2.2. Optimal Mixing Duration for PQ Standard Solution and TSNPs

- •

- The most widely accepted definition of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is the ratio of the average peak height above the baseline to the standard deviation of the peak height. Another way to define the SNR is as the peak height above the baseline compared to the baseline noise or as the root mean square (RMS) value of a flat region in the spectrum [43]. Therefore, in this research, the SNR calculation was performed using the equation shown in Equation (2).

- •

- The enhancement factor (EF) is the ratio of the SERS signal to the Raman signal that would be obtained for the same molecule under the same conditions. It indicates the amplification of the Raman signal due to the presence of nanostructured metallic surfaces, with the EF typically ranging from 104 to 106 [44]. Therefore, in this research, the EF calculation was performed using the equation presented in Equation (3).

- •

- The probability of the primary peak appearance in the detection area is represented as a red mapping grid with varying color intensities. The brightest red regions indicate the highest Raman signal intensity, which gradually decreases with darker shades of red, eventually turning to black, indicating the absence of the primary peak.

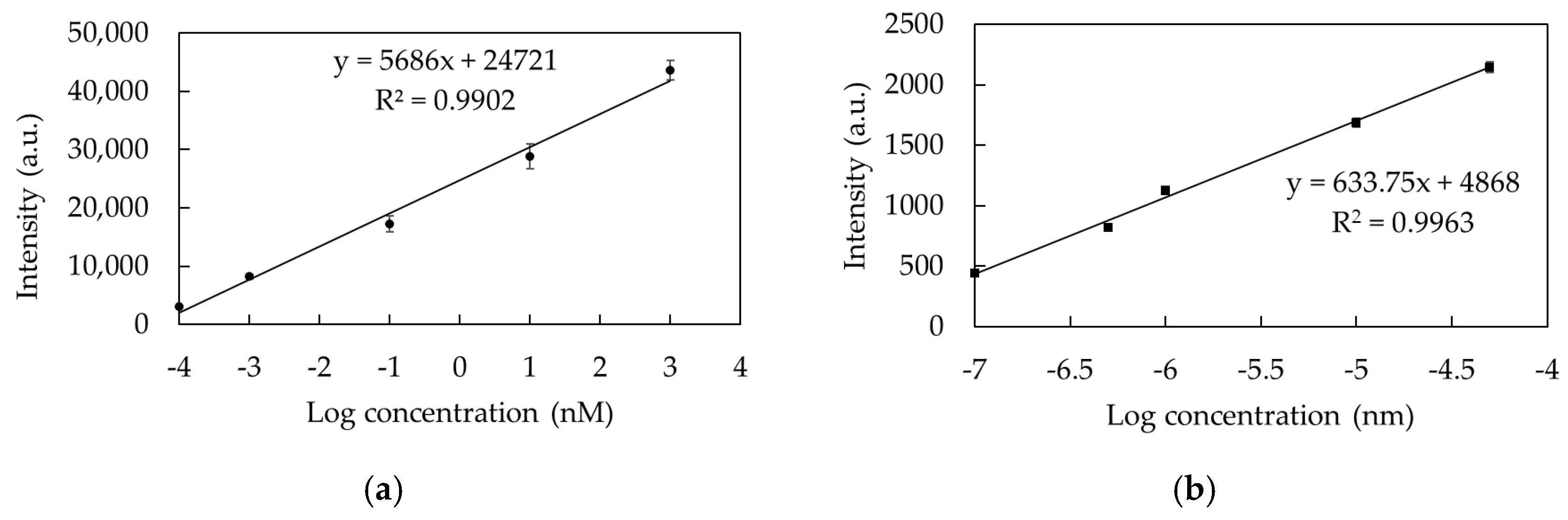

3.2.3. Performance of TSNP Colloidal SERS

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alexandratos, N.; Bruinsma, J. World Agriculture Towards 2030/2050: The 2012 Revision. ESA Working Paper 2012. Available online: http://www.fao.org/docrep/016/ap106e/ap106e.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Tripathi, A.D.; Mishra, R.; Maurya, K.K.; Singh, R.B.; Wilson, D.W. Estimates for World Population and Global Food Availability for Global Health. In The Role of Functional Food Security in Global Health; Singh, R.B., Watson, R.R., Takahashi, T., Eds.; Elsevier Inc.: Oxford, UK, 2019; Volume 3, pp. 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Agriculture Global Market Report 2024. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/agriculture?srsltid=AfmBOorWyWanY8zhkXgyHkZpR1WRFXEpc_1pEBWknhQfxRKN4ucgMxyq#product--related-products (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Lin, M.H.; Sun, L.; Kong, F.; Lin, M. Rapid Detection of Paraquat Residues in Green Tea using Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS) Coupled with Gold Nanostars. Food Control 2021, 130, 108280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán, M.L.; Corrado, G.; Francioso, O.; Sanchez-Cortes, S. Interaction of Soil Humic Acids with Herbicide Paraquat Analyzed by Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering and Fluorescence Spectroscopy on Silver Plasmonic Nanoparticles. Anal. Chim. Acta 2011, 699, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullahi, K.; Saleh, K.J.; Mzungu, I. Effect of Atrazine, 2,4-D Amine, Glyphosate and Paraquat Herbicides on Soil Microbial Population. J. Environ. Microbiol. Toxicol. 2022, 10, 19–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.; Gaudard, L. Paraquat, diuron and atrazine for the renewal of chemical weed control in northern Cameroon. Agriculture et développement, Special Issue, May 1997. Available online: https://agritrop.cirad.fr/388926/1/document_388926.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Vaccari, C.; Dib, R.E.; de Camargo, L.V. Paraquat and Parkinson’s Disease: A Systematic Review Protocol According to the OHAT Approach for Hazard Identification. BioMed Cent. 2017, 6, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paraquat at 63-The Story of a Controversial Herbicide and Its Regulations: It Is Time to Put People and Public Health First When Regulating Paraquat. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/380874772_Paraquat_at_63_the_story_of_a_controversial_herbicide_and_its_regulations_It_is_time_to_put_people_and_public_health_first_when_regulating_paraquat (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Chamchan, C.; Kanchanachitra, M.; Podhisita, C.; Samutachak, B.; Niyomsilpa, S. 10 Outstanding Situations. In Thai Health 2019; Institute for Population and Social Research, Mahidol University: Salaya, Thailand, 2019; pp. 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Willer, H.; Prasad, R.P. The World of Organic Agriculture, 25th ed.; Research Institute of Organic Agriculture and Organics International: Frick, Switzerland; Bonn, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. EPA. 2018 Edition of the Drinking Water Standards and Health Advisories Tables; U.S. Environmental Protection Agency: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2022-01/dwtable2018.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- Thani, S.; Tadpitcha Promchote, P.; Grudpan, J.; Jutagate, T. Effect of Concentrations of Glyphosate, Paraquat and Cypermethrin on Mortality of Red Claw Crayfish Cherax Quadricarinatus (von Martens, 1868). J. Sci. Technol. Ubon Ratchathani Univ. 2022, 24, 64–71. [Google Scholar]

- Rajaram, R.; Neelakantan, L. Recent Advances in Estimation of Paraquat Using Various Analytical Techniques: A Review. Results Chem. 2023, 5, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFOAM EU Group. Guideline for Pesticide Residue Contamination for International Trade in Organic; IFOAM EU Group: Brussels, Belgium, 2012; Available online: https://www.organicseurope.bio/content/uploads/2020/09/ifoameu_regulation_guideline_for_pesticide_residue_contamination_for_international_trade_in_organic_2012.pdf (accessed on 30 August 2024).

- Srinivasan, P. Pests, pesticides and regulations. In Paraquat; International Institute of Biotechnology and Toxicology (IIBT): New Delhi, India, 2003; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- De Góes, R.E.; Muller, M.; Fabris, J.L. Spectroscopic Detection of Glyphosate in Water Assisted by Laser-Ablated Silver Nanoparticles. Sensor 2017, 17, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wu, J.; Gao, H.; Liu, G.; Tian, Z.; Feng, J.; Gua, L.; Xie, J. Rapid On-Site Detection of Paraquat in Biologic Fluids by Iodide-Facilitated Pinhole Shell-Isolated Nanoparticle-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. R. Soc. Chem. 2016, 6, 59919–59926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Wu, X.; Dong, P.; Chen, J.; Xiao, R. Hotspots Engineering by Grafting Au@Ag Core-Shell Nanoparticles on The Au Film Over Slightly Etched Nanoparticles Substrate for On-Site Paraquat Sensing. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016, 86, 944–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botta, R.; Eiamchai, P.; Horatiu, M.; Limwichean, S.; Chananonnawathorn, C.; Patthanasettakul, V.; Maezono, R.; Jomphoak, A.; Nuntawong, N. 3D Structured Laser Engraves Decorated with Gold Nanoparticle SERS Chip for Paraquat Herbicide Detection in Environments. Sens. Actuators B 2020, 304, 127327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaoa, R.; Choia, N.; Changb, S.I.; Kangc, S.H.; Songd, J.M.; Choe, S.I.; Lima, D.W.; Chooa, J. Highly Sensitive Trace Analysis of Paraquat Using a Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Microdroplet Sensor. Anal. Chim. Acta 2010, 681, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, H.; Xie, Y.; Wei, Q.; Sun, D.W. Anchoring Au on UiO-66 Surface with Thioglycolic Acid for Simultaneous SERS Detection and Diquat Residues in Cabbage. Microchem. J. 2023, 190, 108563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, M.; Hussain, H.; Sun, D.W.; Pu, H. Rapid Detection of Paraquat Residue in Fruit Samples using Mercaptoacetic Acid Functionalized Au@AgNR SERS Substrate. Microchem. J. 2023, 189, 108558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dao, T.C.; Luong, T.Q.N.; Cao, T.A.; Nguyen, N.H.; Kieu, N.M.; Luong, T.T.; Le, V.V. Trace detection of Herbicides by SERS Technique, using SERS-Active Substrates Fabricated from Different Silver Nanostructures Deposited on Silicon. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2015, 6, 035012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Wen, J.; Zhang, M.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Du, Y. Design of Hybrid Nanostructural Array to Manipulate SERS-Active Substrates by Nanosphere Lithography. ACS Appl. Mater 2017, 9, 7710–7716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horprathum, M.; Eiamchai, P.; Limnonthakul, P.; Nuntawong, N.; Chindaudom, P.; Pokaipisit, A.; Limsuwan, P. Structural, Optical and Hydrophilic Properties of Nanocrystalline TiO2 Ultra-Thin Films Prepared by Pulsed DC Reactive Magnetron Sputtering. J. Alloys Compd. 2011, 509, 4520–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Man, B.; Jiang, S.; Wang, J.; Wei, J.; Xu, S.; Liu, H.; Gao, S.; Liu, H.; Li, Z.; et al. Graphene/Cu Nanoparticles Hybrids Fabricated by Chemical Vapor Deposition as Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Substrate for Label-Free Detection of Adenosine. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 10977–10987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anh, C.T.; Cao, D.T.; Ngan, L.T.Q. Synthesis of colloidal snowflake-like silver nanoparticles and their use for SERS detection of pesticide imidacloprid at trace levels. Opt. Mater. 2024, 157, 116422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saute, B.; Narayanan, R. Solution-Based Direct Readout Surface Enhanced Raman Spectroscopic (SERS) detection of Ultra-Low Levels of Thiram with Dogbone Shape Gold Nanoparticles. R. Soc. Chem. 2011, 136, 527–532. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, H.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, S.J.; Liu, L.; Zho, Y.M.; Xu, H.J. Ultrasensitive and Quantitative Detection of Paraquat on Fruits Skins via Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2015, 213, 452–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilot, R.; Signorini, R.; Durante, C.; Orian, L.; Bhamidipati, M.; Fabris, L. A Review on Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Biosensors 2019, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.; Frontirea, R.R.; Henry, A.I.; Ringe, E.; Van Duyne, R.P. SERS: Materials, Applications, and the Future. Materialstoday 2012, 15, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, N.A.; Fronzi, M.; Shapter, J.G. Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Using a Silver Nanostar Substrate for Neonicotinoid Pesticides Detection. Sensors 2024, 24, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logan, N.; Haughey, S.A.; Liu, L.; Burns, D.T.; Quinn, B.; Cao, C.; Elliott, C.T. Handheld SERS coupled with QuEChERs for the sensitive analysis of multiple pesticides in basmati rice. NPJ Sci. Food 2022, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, N.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nghi, N.Đ.; Kim, Y.H.; Joo, S.W. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Detection of Fipronil Pesticide Adsorbed on Silver Nanoparticles. Sensors 2019, 19, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phetsahai, A.; Eiamchai, P.; Thamaphat, K.; Limsuwan, P. The Morphological Evolution of Self-Assembled Silver Nanoparticles under Photoirradiation and Their SERS Performance. Processes 2023, 11, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velgosova, O.; Măcák, L.; Cižmárová, F.; Mára, V. Influence of Reagents on the Synthesis Process and Shape of Silver Nanoparticle. Materials 2022, 15, 6829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krajczewski, J.; Joubert, V.; Kudelski, A. Light-Induced Transformation of Citrate-Stabilized Silver Nanoparticles: Photochemical Method of Increase of SERS Activity of Silver Colloids. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 456, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Gabriella, S.; Millstone, J.E.; Mirkin, C.A. Mechanistic Study of Photomediated Triangular Silver Nanoprism Growth. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8337–8344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhung, N.T.H.; Dat, N.T.; Thi, C.M.; Viet, P.V. Fast and Simple Synthesis of Triangular Silver Nanoparticles under the Assistance of Light. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 594, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Brioude, A.; Pileni, M.P. Silver Nanodisks: Optical Properties Study Using the Discrete Dipole Approximation Method. J. Phys. Chem. B 2005, 109, 23371–23377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandaria, S.; Parihar, V.S.; Kellomäki, M.; Mahato, M. Highly Selective and Flexible Silver Nanoparticles-Based Paper Sensor for on-site Colorimetric Detection of Paraquat Pesticide. R. Soc. Chem. 2014, 14, 28844–28853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.L.; Leng, Y.C.; Lin, M.L.; Cong, X.; Tan, P.H. Signal-to-noise ratio of Raman signal measured by multichannel detectors. Chin. Phys. B 2021, 30, 097807. [Google Scholar]

- Le Ru, E.C.; Etchegoin, P.G. Quantifying SERS enhancements. Mater. Res. Soc. 2013, 38, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, D.; Zou, Y.; Ni, D.; Ye, J.; Yu, Z.; Chen, Q.; Jin, S.; et al. Fabrication of Fe3O4@Ag Magnetic Nanoparticles for Highly Active SERS Enhancement and Paraquat Detection. Microchem. J. 2022, 173, 107019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, L.; Dai, P.; Ouyang, L.; Zhu, L. A Sensitive and Reproducible SERS Sensor based on Natural Lotus Leaf for Paraquat Detection. Microchem. J. 2020, 160, 105728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, C.; Liu, X.; Xin, L.; Fang, Y. Self-Assembled Au Nanoparticle Arrays on Thiol-Functionalized Resin Beads for Sensitive Detection of Paraquat by Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2014, 415, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamkrua, N.; Ngernsutivorakul, T.; Limwichean, S.; Eiamchai, P.; Chananonnawathorn, C.; Pattanasetthakul, V.; Ricco, R.; Choowongkomon, K.; Horprathum, M.; Nuntawong, N.; et al. Au Nanoparticle-Based Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy Aptasensors for Paraquat Herbicide Detection. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6, 1072–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Raman Shift (cm−1) | Vibrational Bond |

|---|---|

| 841 | carbon–nitrogen single bonds (C-N) |

| 1192 | carbon–carbon double bonds (C=C) |

| 1298 | carbon–carbon single bonds (C-C) |

| 1651–1655 | carbon–nitrogen double bonds (C=N) |

| Mixing Time (min) | SERS Signal Intensity (a.u.) | SNR | EF |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-SERS (control) | 20.77 | 3.15 | 1 |

| 5 | 23,215.80 | 110.78 | 117.76 |

| 10 | 52,302.80 | 255.84 | 2518.19 |

| 15 | 23,215.80 | 133.99 | 1117.76 |

| 20 | 18,845.97 | 182.62 | 907.36 |

| 30 | 28,236.47 | 186.91 | 1359.48 |

| 45 | 13,623.97 | 126.70 | 655.94 |

| Mixing Time (min) | SERS Signal Intensity (a.u.) | EF |

|---|---|---|

| blank (pure 10−4 M) | 21 | 3 |

| 10−6 | 30,775 | 119 |

| 10−8 | 21,117 | 190 |

| 10−10 | 14,460 | 114 |

| 10−12 | 7371 | 364 |

| 10−13 | 2286 | 65 |

| 5 × 10−14 | 2209 | 12 |

| 5 × 10−16 | 708 | 16 |

| 10−16 | 629 | 43 |

| Sample | Calibration Curve Equation | TSNP SERS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Intensity | Recovery | ||

| tap water (Suphanburi) | y = 5575.6x − 3050.4 | 7516.10 | 92.78 |

| tap water (Bangkok) | y = 10,491x − 4638.8 | 15,931.95 | 97.48 |

| River (Chao Phraya) | y = 3786.7x + 3595 | 10,742.35 | 96.19 |

| drinking water | y = 2.8055 × 103.7413 | 12,841.50 | 113.58 |

| SERS Type | Sample | LOD (M) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe3O4@Ag magnetic NPs | water | 10−10 | [45] |

| AgNPs on lotus leaf | water | 4.8 × 10−12 | [46] |

| Au NPs–resin sphere | water | 10−12 | [47] |

| AuNPs SERS-based aptasensor | water | 1.4 × 10−7 | [48] |

| AuNPs on 3D structured aluminum sheet | water | 10−7 | [20] |

| TSNP colloidal SERS | DI water | 10−16 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ketkong, A.; Sutthibutpong, T.; Nuntawong, N.; Chutrakulwong, F.; Thamaphat, K. Sensitive Detection of Paraquat in Water Using Triangular Silver Nanoplates as SERS Substrates for Sustainable Agriculture and Water Resource Management. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231827

Ketkong A, Sutthibutpong T, Nuntawong N, Chutrakulwong F, Thamaphat K. Sensitive Detection of Paraquat in Water Using Triangular Silver Nanoplates as SERS Substrates for Sustainable Agriculture and Water Resource Management. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231827

Chicago/Turabian StyleKetkong, Apinya, Thana Sutthibutpong, Noppadon Nuntawong, Fueangfakan Chutrakulwong, and Kheamrutai Thamaphat. 2025. "Sensitive Detection of Paraquat in Water Using Triangular Silver Nanoplates as SERS Substrates for Sustainable Agriculture and Water Resource Management" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231827

APA StyleKetkong, A., Sutthibutpong, T., Nuntawong, N., Chutrakulwong, F., & Thamaphat, K. (2025). Sensitive Detection of Paraquat in Water Using Triangular Silver Nanoplates as SERS Substrates for Sustainable Agriculture and Water Resource Management. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1827. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231827