The Reconstruction of Sesame Protein-Derived Amyloid Fibrils Alleviates the Gastric Digestion Instability of β-Carotene Nanoparticles

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Sesame Protein Amyloid Fibrils

2.3. Simulated Gastric Digestion of Sesame Protein Amyloid Fibrils

2.4. ThT Fluorescence Spectroscopy

2.5. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

2.6. Rheological Properties of Amyloid Fibril Digesta

2.7. Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

2.8. Gel Permeation Chromatography (GPC)

2.9. Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS)

2.10. Fabrication of β-Carotene Nanoparticles Encapsulated by Native Protein/Fibrils

Physical Properties of β-Carotene Delivery System

2.11. In Vitro Digestion of β-Carotene Nanoparticles Encapsulated by Native Protein/Fibrils

2.12. Digestion Rates of Transport Carriers (Native Protein and Amyloid Fibrils)

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

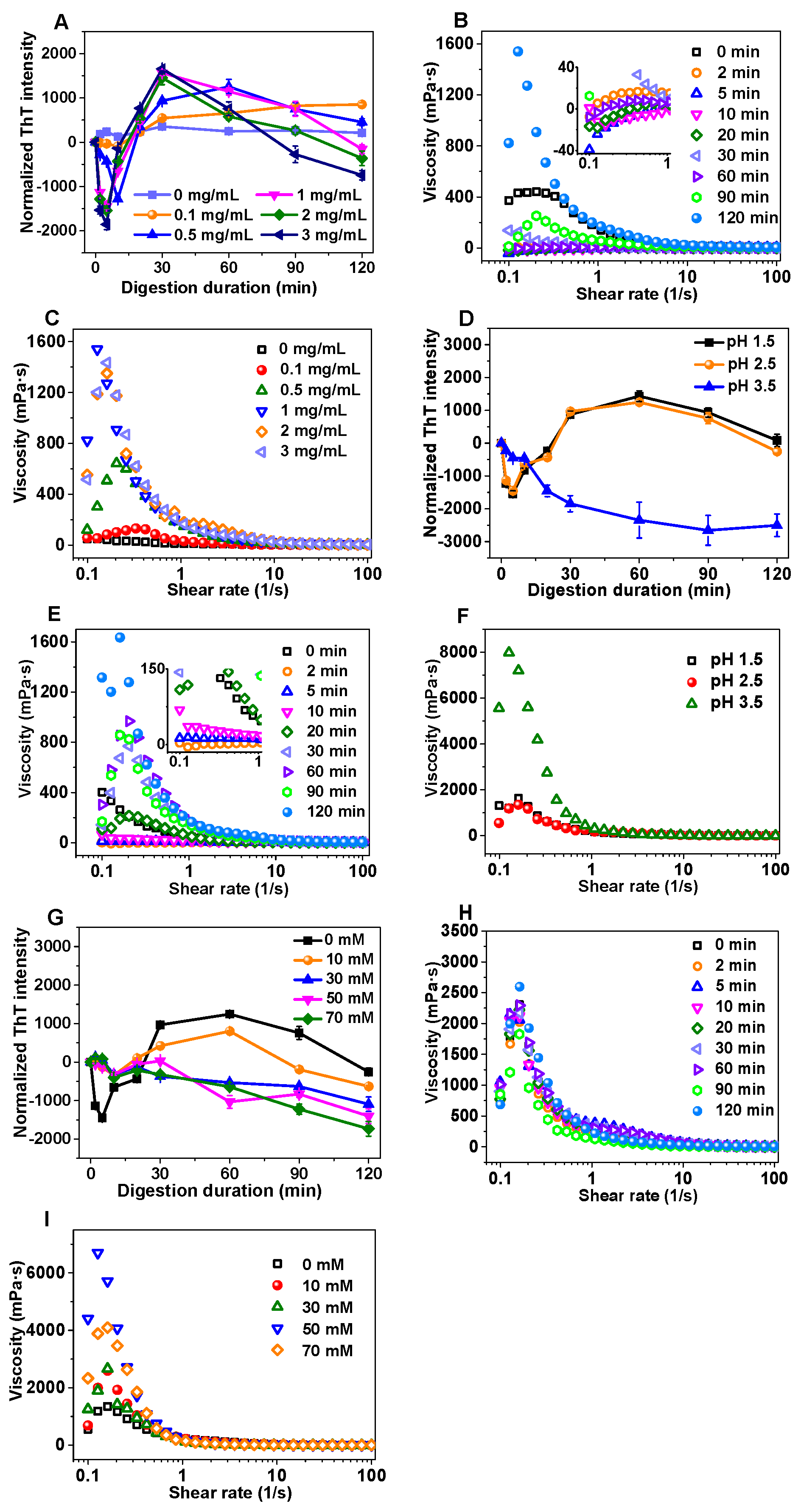

3.1. Changes in Normalized ThT Fluorescence Intensity and Apparent Viscosity of Amyloid Fibrils During Gastric Digestion

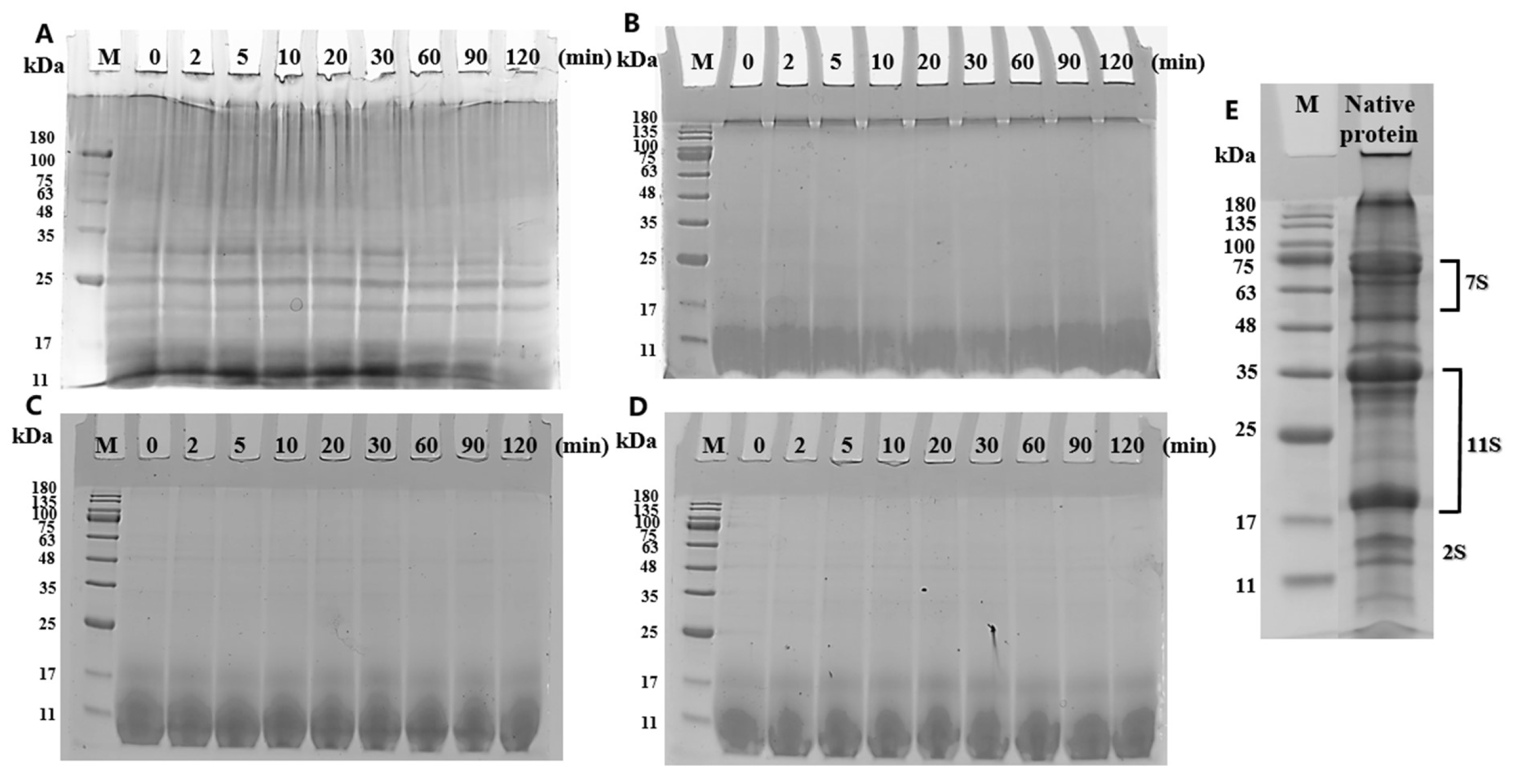

3.2. SDS-PAGE Images of Amyloid Fibrils During Gastric Digestion

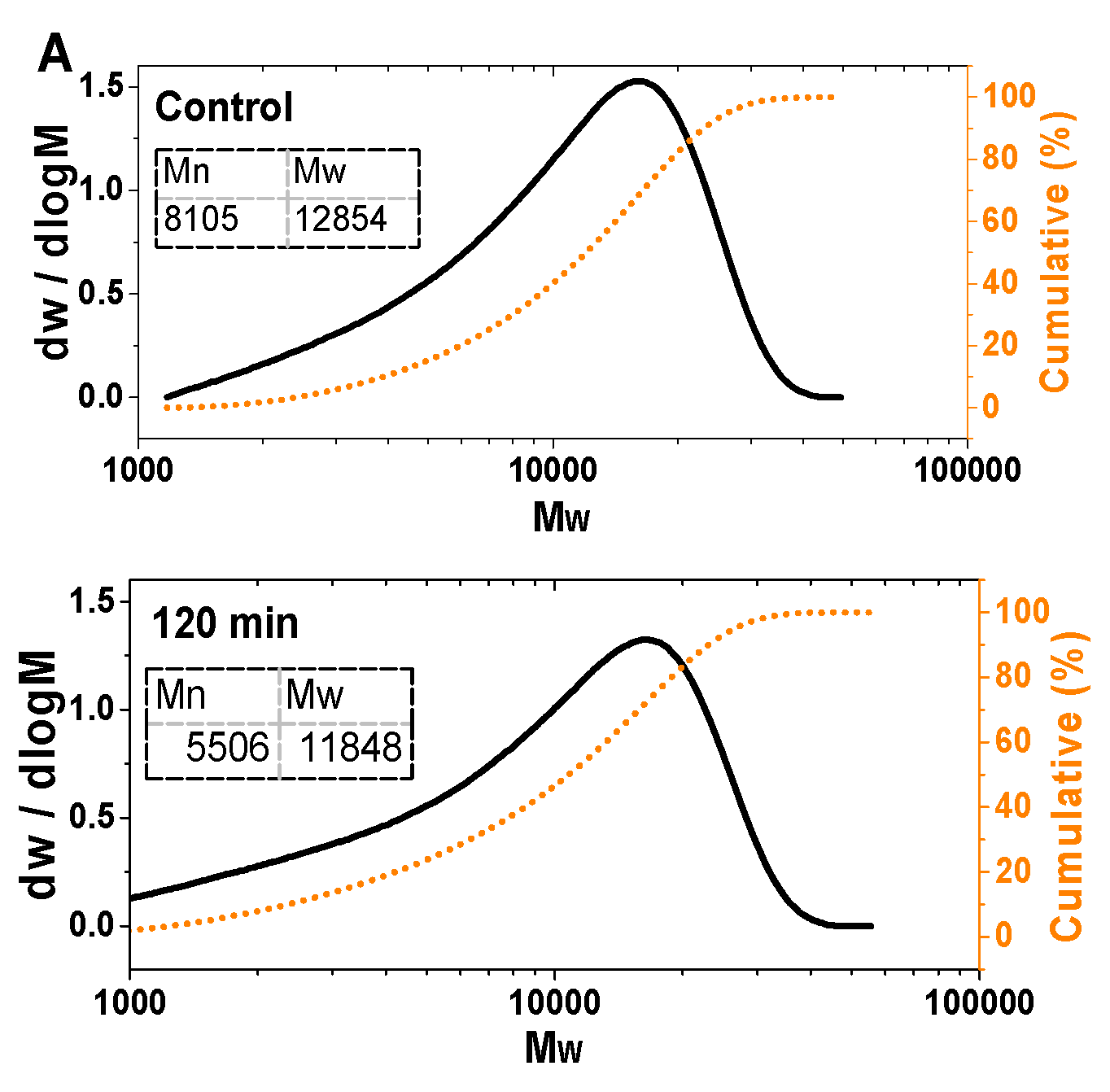

3.3. Gel Permeation Chromatography of Amyloid Fibrils Before and After Gastric Digestion

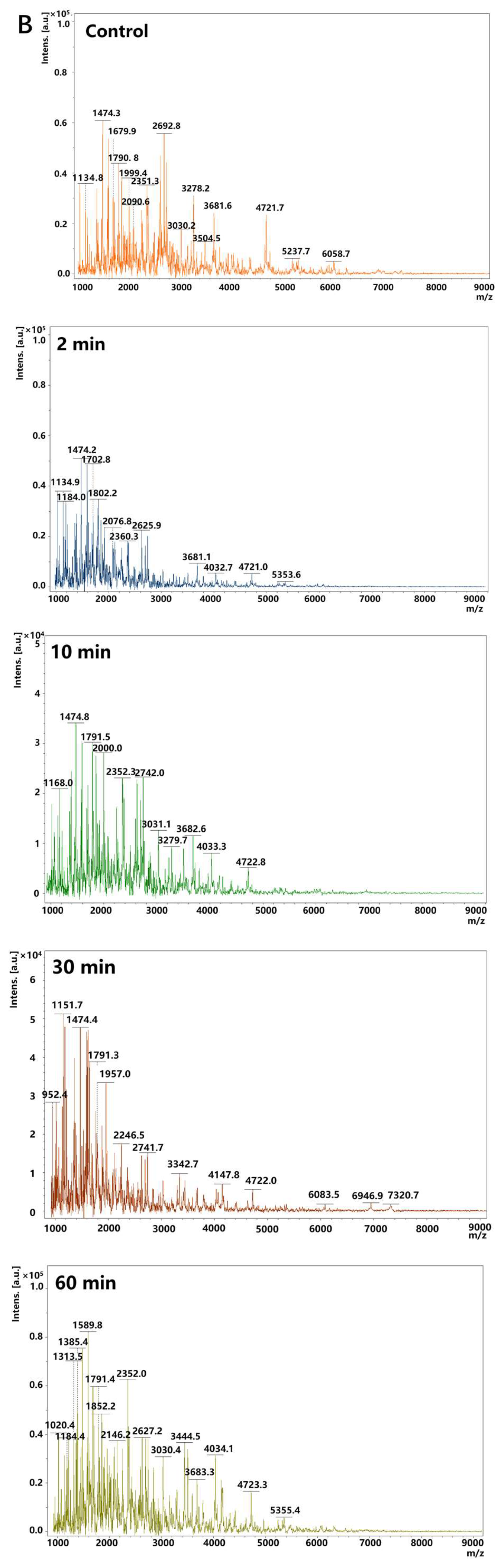

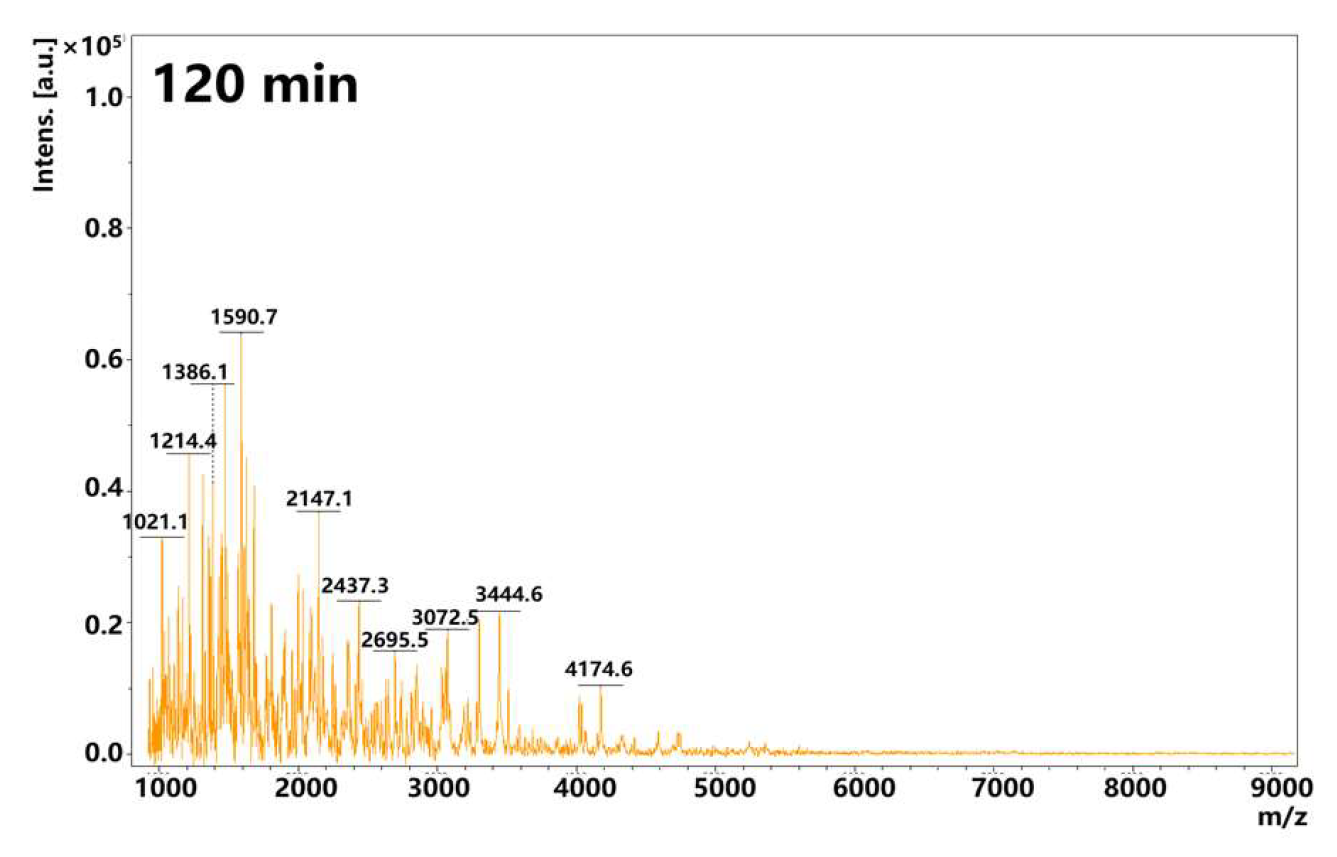

3.4. Mass Spectrometric Analysis of Amyloid Fibrils During Gastric Digestion

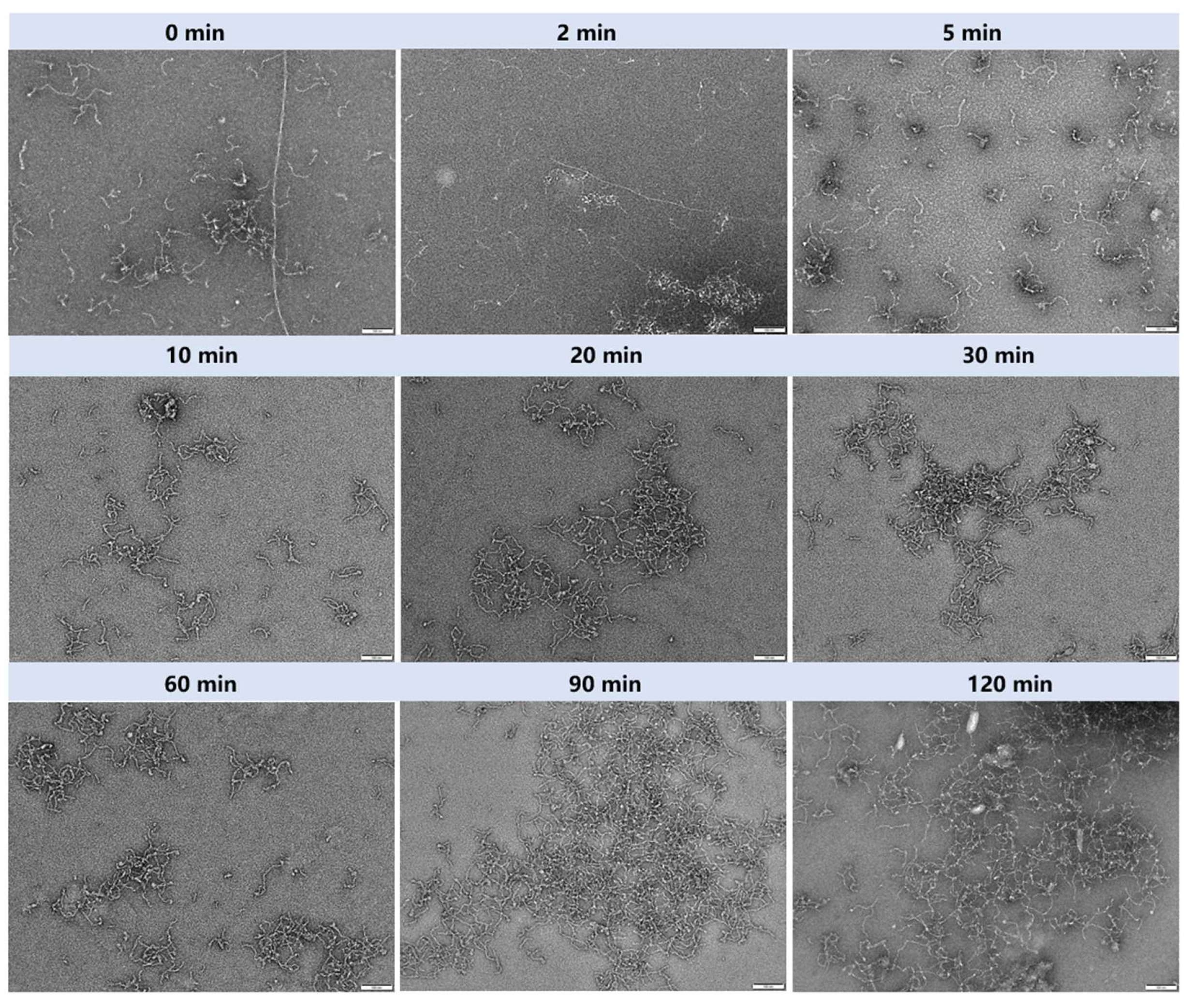

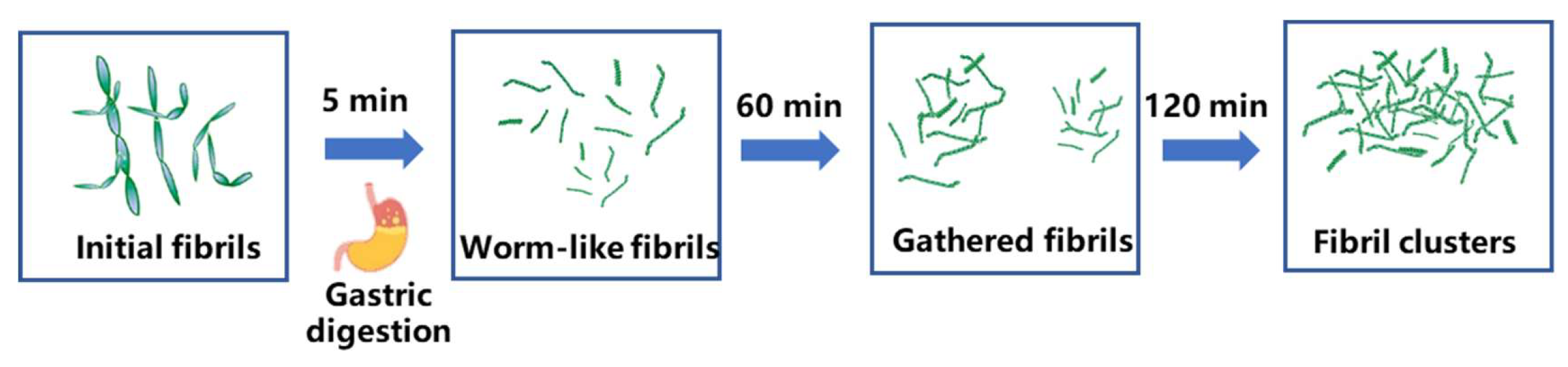

3.5. Morphological Changes in Amyloid Fibrils During Gastric Digestion

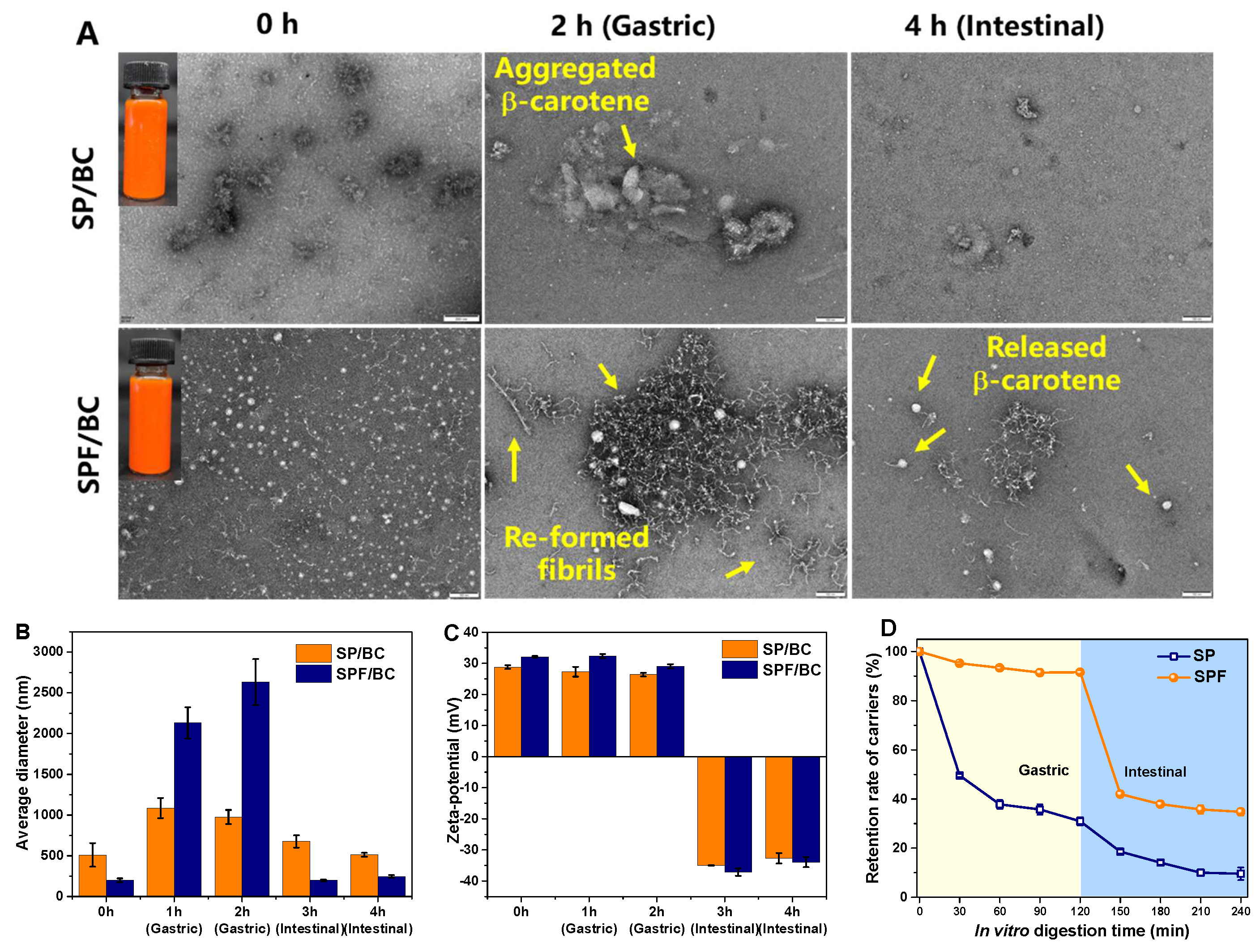

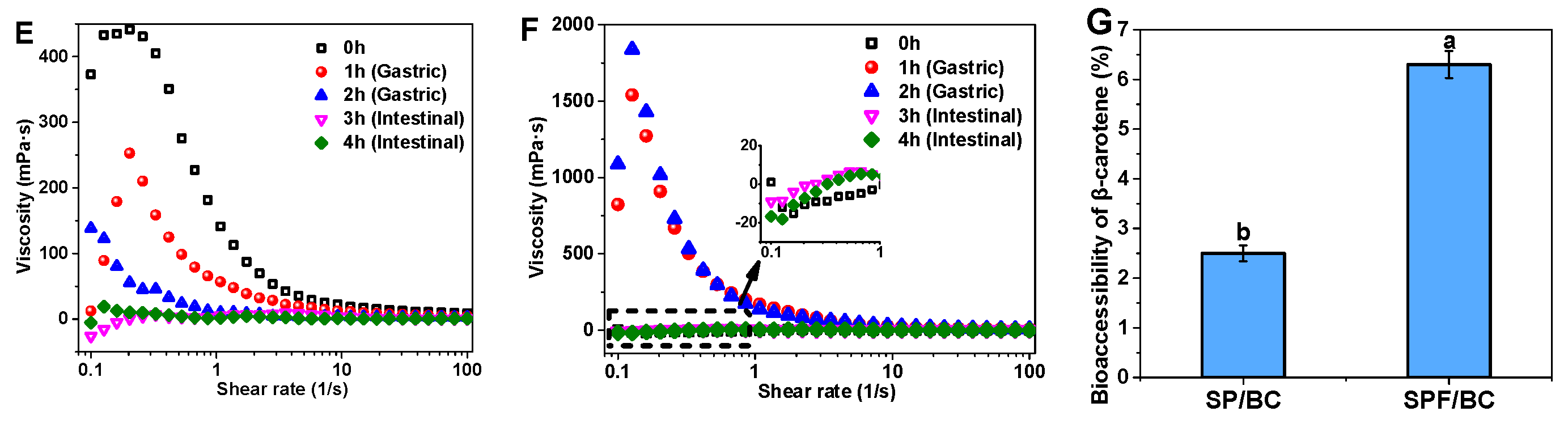

3.6. Physical Properties of β-Carotene Delivery System

3.7. In Vitro Simulated Digestion of β-Carotene Transport Systems

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liu, M.; Liu, H.; He, B.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, J. Plant-based protein amyloid fibrils: Origins, formation, extraction, applications, and safety. Food Chem. 2025, 469, 142559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, N.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Wang, X. Formation, structure and functional characteristics of amyloid fibrils formed based on soy protein isolates. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 254, 127956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Zhou, J.; Soon, W.L.; Kutzli, I.; Molière, A.; Diedrich, S.; Radiom, M.; Handschin, S.; Li, B.; Li, L.; et al. Food amyloid fibrils are safe nutrition ingredients based on in-vitro and in-vivo assessment. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 6806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Yu, S.J.; Shi, C.; Gu, J.; Shao, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.Q.; Mezzenga, R. Amyloid-Polyphenol Hybrid Nanofilaments Mitigate Colitis and Regulate Gut Microbial Dysbiosis. ACS Nano 2020, 14, 2760–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Shen, Y.; Adamcik, J.; Fischer, P.; Schneider, M.; Loessner, M.J.; Mezzenga, R. Polyphenol-Binding Amyloid Fibrils Self-Assemble into Reversible Hydrogels with Antibacterial Activity. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 3385–3396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Lin, L.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Tao, N. Astaxanthin complexes of five plant protein fibrils: Aggregation behavior, interaction, and delivery properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 162, 110995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Everett, D.W.; Huang, M.; Zhai, Y.; Li, T.; Fu, Y. Amyloid fibrils for β-carotene delivery—Influence of self-assembled structures on binding and in vitro release behavior. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; McClements, D.J.; Liu, X.B.; Liu, F.G. Overcoming Biopotency Barriers: Advanced Oral Delivery Strategies for Enhancing the Efficacy of Bioactive Food Ingredients. Adv. Sci. 2024, 11, e2401172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.; He, C.; Woo, M.W.; Xiong, H.; Hu, J.; Zhao, Q. Formation of fibrils derived from whey protein isolate: Structural characteristics and protease resistance. Food Funct. 2019, 10, 8106–8115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheong, D.Y.; Roh, S.; Park, I.; Lin, Y.; Lee, Y.-H.; Lee, T.; Lee, S.W.; Lee, D.; Jung, H.G.; Kim, H.; et al. Proteolysis-driven proliferation and rigidification of pepsin-resistant amyloid fibrils. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 227, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassé, M.; Ulluwishewa, D.; Healy, J.; Thompson, D.; Miller, A.; Roy, N.; Chitcholtan, K.; Gerrard, J.A. Evaluation of protease resistance and toxicity of amyloid-like food fibrils from whey, soy, kidney bean, and egg white. Food Chem. 2016, 192, 491–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Ahmad, T.; Belwal, T.; Aadil, R.M.; Siddique, M.; Pang, L.; Xu, Y. A review on protein based nanocarriers for polyphenols: Interaction and stabilization mechanisms. Food Innov. Adv. 2023, 2, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhan, J.; Liu, X.; Guan, B.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, D.; Wang, W.; Liu, G.; Zhang, H.; Liu, D. Functionalization of oilseed proteins via fibrillization: Comparison in structural characteristics, digestibility and 3D printability of amyloid fibrils. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 162, 111019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivabalan, S.; Ross, C.F.; Tang, J.; Sablani, S.S. Physical, thermal, and storage stability of multilayered emulsion loaded with β-carotene. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 244–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Shen, S.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Ibrahim, A.N.; Zhang, Y. Protection mechanism of β-carotene on the chlorophyll photostability through aggregation: A quantum chemical perspective. Food Innov. Adv. 2024, 3, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-Y.; Lai, Y.-R.; How, S.-C.; Lin, T.-H.; Wang, S.S.S. Encapsulation with a complex of acidic/alkaline polysaccharide-whey protein isolate fibril bilayer microcapsules enhances the stability of β-carotene under acidic environments. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2024, 160, 105344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liao, W.; Tong, Z.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Mao, L.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y. Impact of biopolymer-surfactant interactions on the particle aggregation inhibition of β-carotene in high loaded microcapsules: Spontaneous dispersibility and in vitro digestion. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 134, 108043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liao, W.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Z.; Li, Q.; Gao, Y. Thermal-induced impact on physicochemical property and bioaccessibility of β-carotene in aqueous suspensions fabricated by wet-milling approach. Food Control 2022, 141, 109155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalali-Jivan, M.; Rostamabadi, H.; Assadpour, E.; Tomas, M.; Capanoglu, E.; Alizadeh-Sani, M.; Kharazmi, M.S.; Jafari, S.M. Recent progresses in the delivery of β-carotene: From nano/microencapsulation to bioaccessibility. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2022, 307, 102750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Liang, R.; Williams, P.A.; Zhong, F. Factors affecting the bioaccessibility of β-carotene in lipid-based microcapsules: Digestive conditions, the composition, structure and physical state of microcapsules. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 77, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Li, L.; Xu, D.; Sheng, B.; Qin, D.; Chen, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, X. Application of ultrasound pretreatment and glycation in regulating the heat-induced amyloid-like aggregation of β-lactoglobulin. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 80, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Gao, Y.; Yuan, F.; Mao, L. Development of κ-carrageenan hydrogels with mechanically stronger structures via a solvent-replacement method. Food Innov. Adv. 2023, 2, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hu, Y.; Cao, Z.; Liang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Xu, Z.; Sui, X. Effect of protease hydrolysis on the structure of acidic heating-induced soy protein amyloid fibrils. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huyst, A.M.R.; Luyckx, T.; Monge-Morera, M.; Van Camp, J.; Delcour, J.A.; Van der Meeren, P. Interfacial and oil-in-water emulsifying properties of ovalbumin enriched in amyloid-like fibrils and peptides. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 166, 111367. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Li, S.; Li, S.; Fang, Y.; Cao, Y. Formation and morphology of flaxseed protein isolate amyloid fibrils as governed by NaCl concentration. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 166, 111300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liao, W.; Tong, Z.; Wei, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Mao, L.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y. Modulating physicochemical properties of β-carotene in the microcapsules by polyphenols co-milling. J. Food Eng. 2023, 359, 111691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Liang, R.; Ye, A.; Singh, H.; Zhong, F. Effects of calcium on lipid digestion in nanoemulsions stabilized by modified starch: Implications for bioaccessibility of β-carotene. Food Hydrocoll. 2017, 73, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, W.; Li, S.; Gu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wang, J. Effects of Starch on the Digestibility of Gluten under Different Thermal Processing Conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019, 67, 7120–7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gül, O.; Gül, L.B.; Parlak, M.E.; Sarıcaoğlu, F.T.; Atalar, İ.; Törnük, F. Effects of high hydrostatic pressure treatment on structural, techno-functional and rheological properties of sesame protein isolate. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 168, 111549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalesi, H.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, C.; Lu, W.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Kadkhodaee, R.; Fang, Y. Influence of amyloid fibril length and ionic strength on WPI-based fiber-hydrogel composites: Microstructural, rheological and water holding properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 148, 109499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loveday, S.M.; Wang, X.L.; Rao, M.A.; Anema, S.G.; Creamer, L.K.; Singh, H. Tuning the properties of β-lactoglobulin nanofibrils with pH, NaCl and CaCl2. Int. Dairy J. 2010, 20, 571–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, L.; Feng, X.; Wu, C.; Wei, J.; Chen, L.; Yu, X.; Liu, Q.; Tang, X. Bromelain hydrolysis and CaCl2 coordination promote the fibrillation of quinoa protein at pH 7. Food Hydrocoll. 2025, 159, 110659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykolenko, S.; Soon, W.L.; Mezzenga, R. Production and characterization of amaranth amyloid fibrils from food protein waste. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 149, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Chen, L.; Liu, F.; Xu, F.; Zhong, F. Improvement of the encapsulation capacity and emulsifying properties of soy protein isolate through controlled enzymatic hydrolysis. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 138, 108444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Sun, X.; Tang, Z.; Cao, Y.; Yu, H.; Wu, M. Enhancing the physical and oxidative stability of hempseed protein emulsion via comparative enzymolysis with different proteases: Interfacial properties of the adsorption layer. Food Res. Int. 2025, 201, 115654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, X.; Wen, B.; Liu, W.; Hou, L.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Y.; Feng, N.; Yang, P.; Ren, H. Polymorphism on the interfacial adhesion of amyloid-like fibrils: Insights from assembly units and secondary structures. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2025, 700, 138375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopalswamy, M.; Kumar, A.; Adler, J.; Baumann, M.; Henze, M.; Kumar, S.T.; Fändrich, M.; Scheidt, H.A.; Huster, D.; Balbach, J. Structural characterization of amyloid fibrils from the human parathyroid hormone. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Proteins Proteom. 2015, 1854, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsumura, K.; Saito, T.; Kugimiya, W.; Inouye, K. Selective proteolysis of the glycinin and β-conglycinin fractions in a soy protein isolate by pepsin and papain with controlled pH and temperature. J. Food Sci. 2004, 69, C363–C367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.T.; Yang, X.Q.; Zhang, J.B. Effects of pepsin hydrolysis on the soy β-conglycinin aggregates formed by heat treatment at different pH. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 49, 1729–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, F.; Zhao, M.; Ning, Z.; Sun-Waterhouse, D.; Sun, B. Soy peptide aggregates formed during hydrolysis reduced protein extraction without decreasing their nutritional value. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 4384–4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yang, Q.; Du, Y.; Chen, H. Evaluation of the impact of stirring on the formation, structural changes and rheological properties of ovalbumin fibrils. Food Hydrocoll. 2022, 128, 107615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ono, M.; Honda, M.; Wahyudiono; Yasuda, K.; Kanda, H.; Goto, M. Production of β-carotene nanosuspensions using supercritical CO2 and improvement of its efficiency by Z-isomerization pre-treatment. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2018, 138, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, K.; Zhou, X.; Wu, H.; Zhang, L.; Liang, L.; Zhang, Y. Research on the release and absorption regularities of free amino acids and peptides in vitro digestion of yeast protein. Food Chem. 2025, 482, 144176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Liao, W.; Wang, Y.; Tong, Z.; Liu, J.; Mao, L.; Yuan, F.; Gao, Y. Hindering interparticle agglomeration of β-carotene by wall material complexation at the solid-liquid interface. J. Food Eng. 2023, 355, 111569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Samples | Average Diameter (nm) | ζ-Potential (mV) | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | Loading Capacity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SP/BC | 510.3 ± 144.7 a | 28.8 ± 0.6 b | 84.2 ± 0.3 b | 0.17 ± 0.05 a |

| SPF/BC | 198.8 ± 23.7 b | 32.1 ± 0.2 b | 91.0 ± 0.2 a | 0.31 ± 0.04 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Tong, H.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, T.; Liu, G.; Liu, D. The Reconstruction of Sesame Protein-Derived Amyloid Fibrils Alleviates the Gastric Digestion Instability of β-Carotene Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231829

Zhang L, Zhang P, Tong H, Zhao Y, Yu T, Liu G, Liu D. The Reconstruction of Sesame Protein-Derived Amyloid Fibrils Alleviates the Gastric Digestion Instability of β-Carotene Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231829

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Liang, Puxuan Zhang, Haocheng Tong, Yue Zhao, Tengfei Yu, Guanchen Liu, and Donghong Liu. 2025. "The Reconstruction of Sesame Protein-Derived Amyloid Fibrils Alleviates the Gastric Digestion Instability of β-Carotene Nanoparticles" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231829

APA StyleZhang, L., Zhang, P., Tong, H., Zhao, Y., Yu, T., Liu, G., & Liu, D. (2025). The Reconstruction of Sesame Protein-Derived Amyloid Fibrils Alleviates the Gastric Digestion Instability of β-Carotene Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1829. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231829