SWCNT-Based Composite Films with High Mechanical Strength and Stretchability by Combining Inorganic-Blended Acrylic Emulsion for Various Thermoelectric Generators

Abstract

1. Introduction

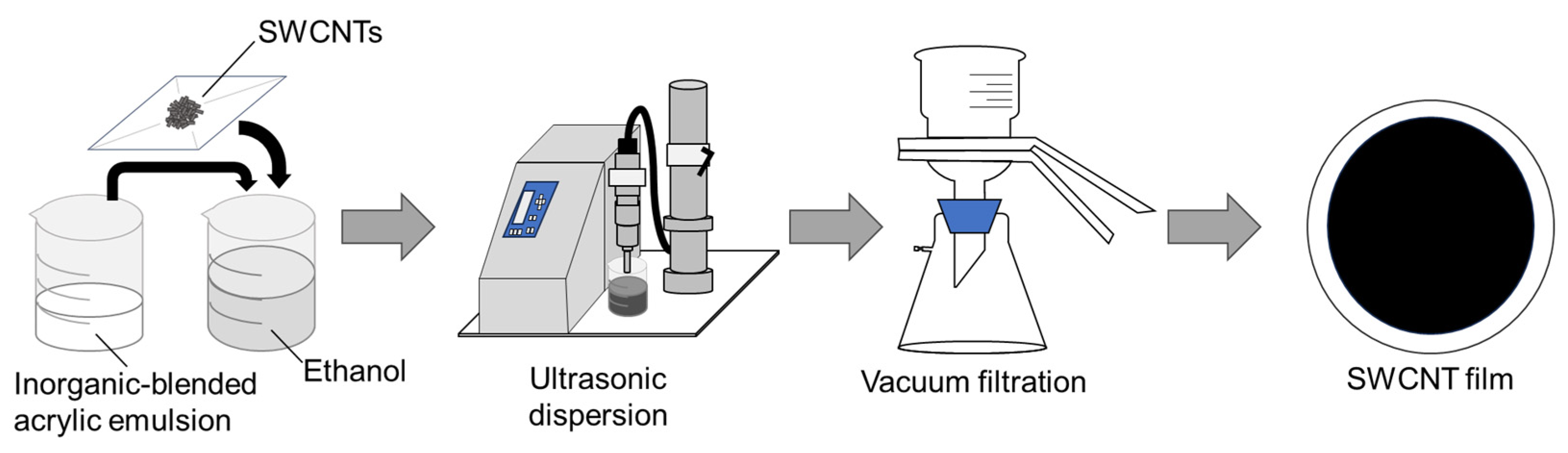

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

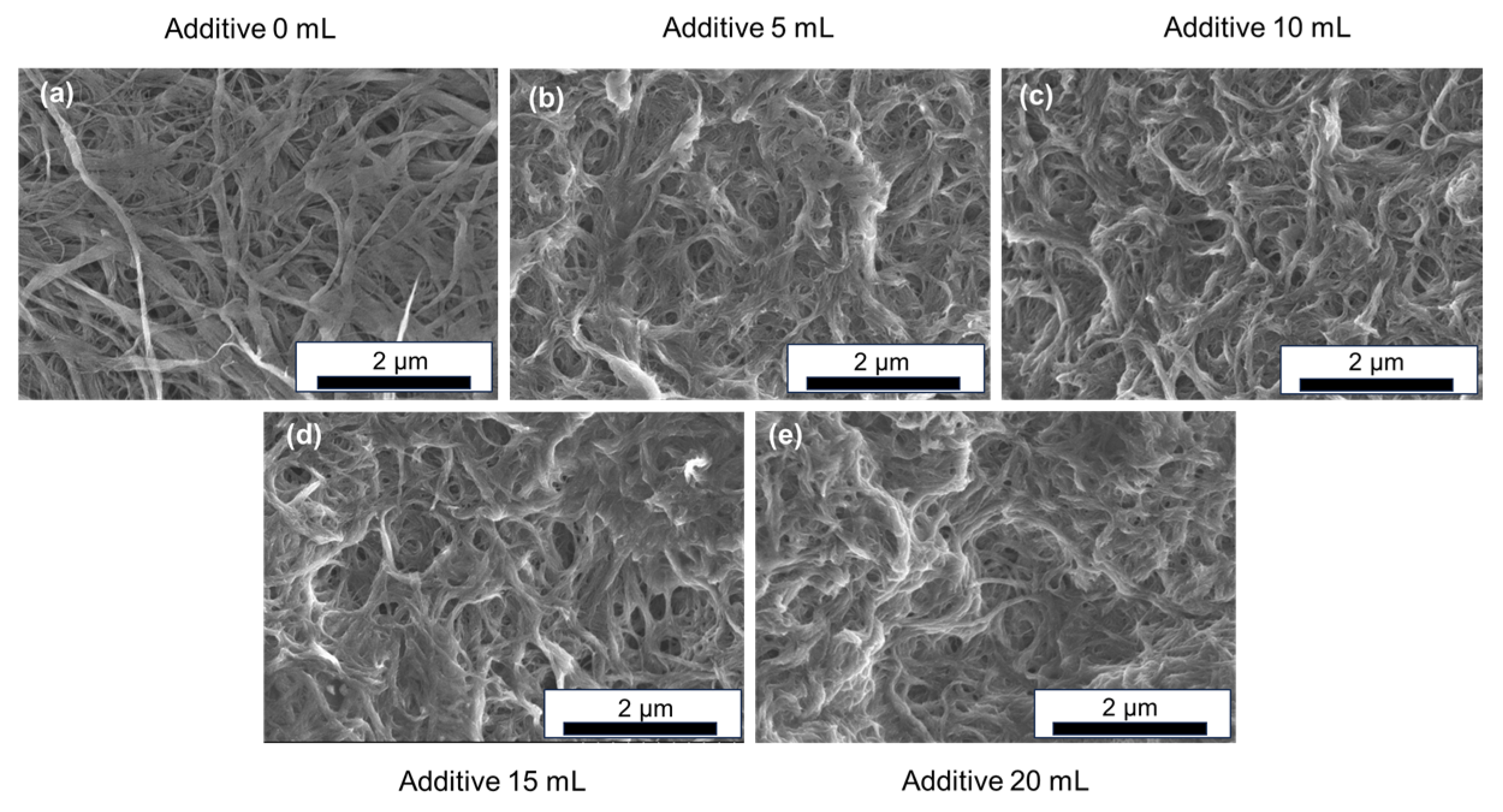

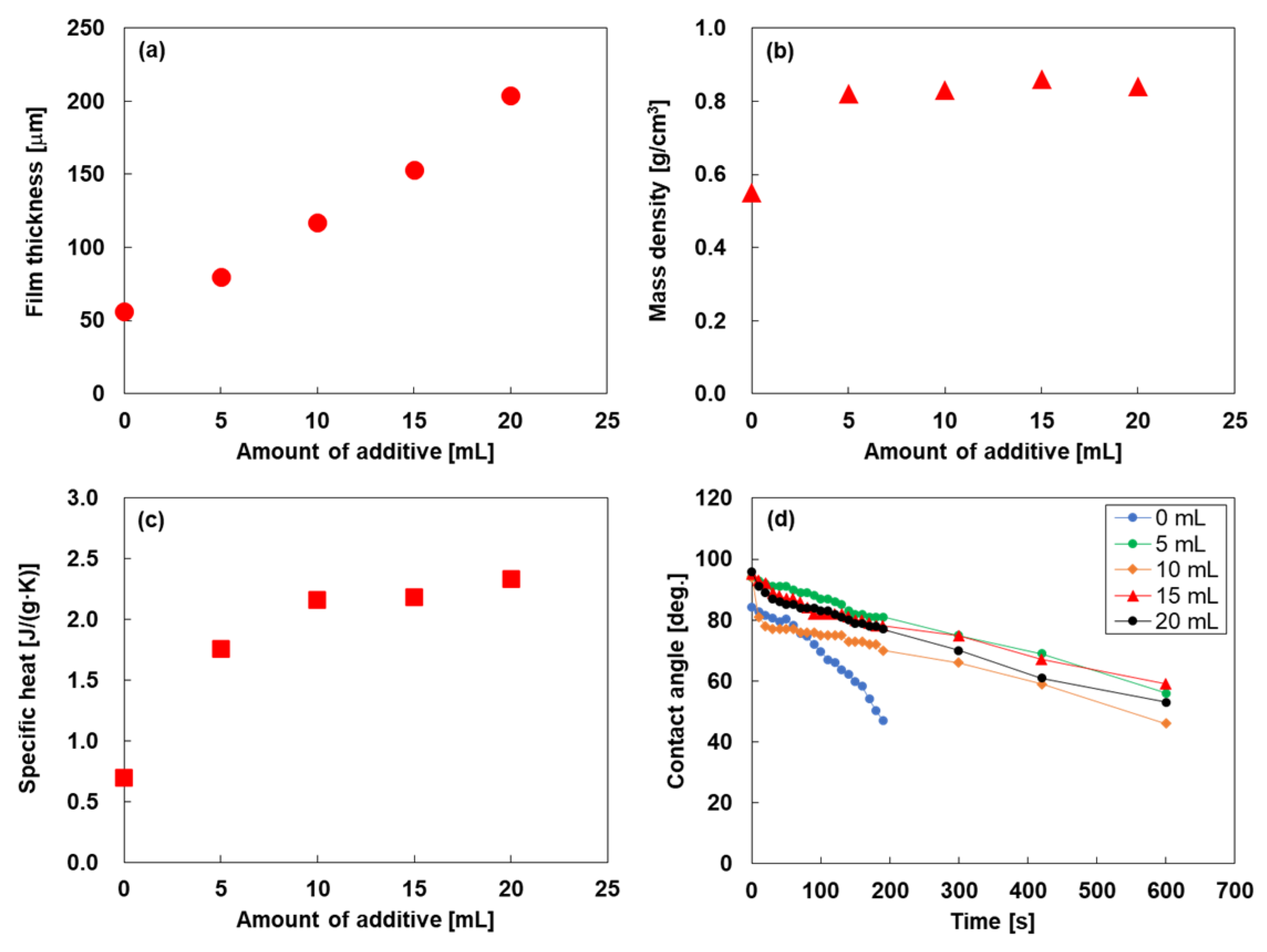

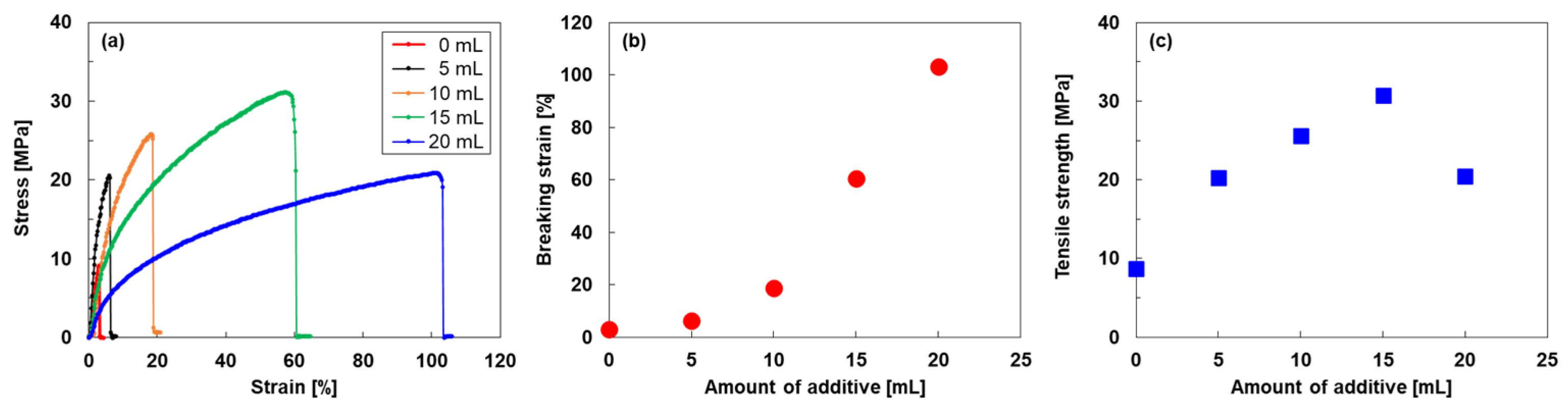

3.1. Structural and Mechanical Properties of SWCNT-Based Composite Films

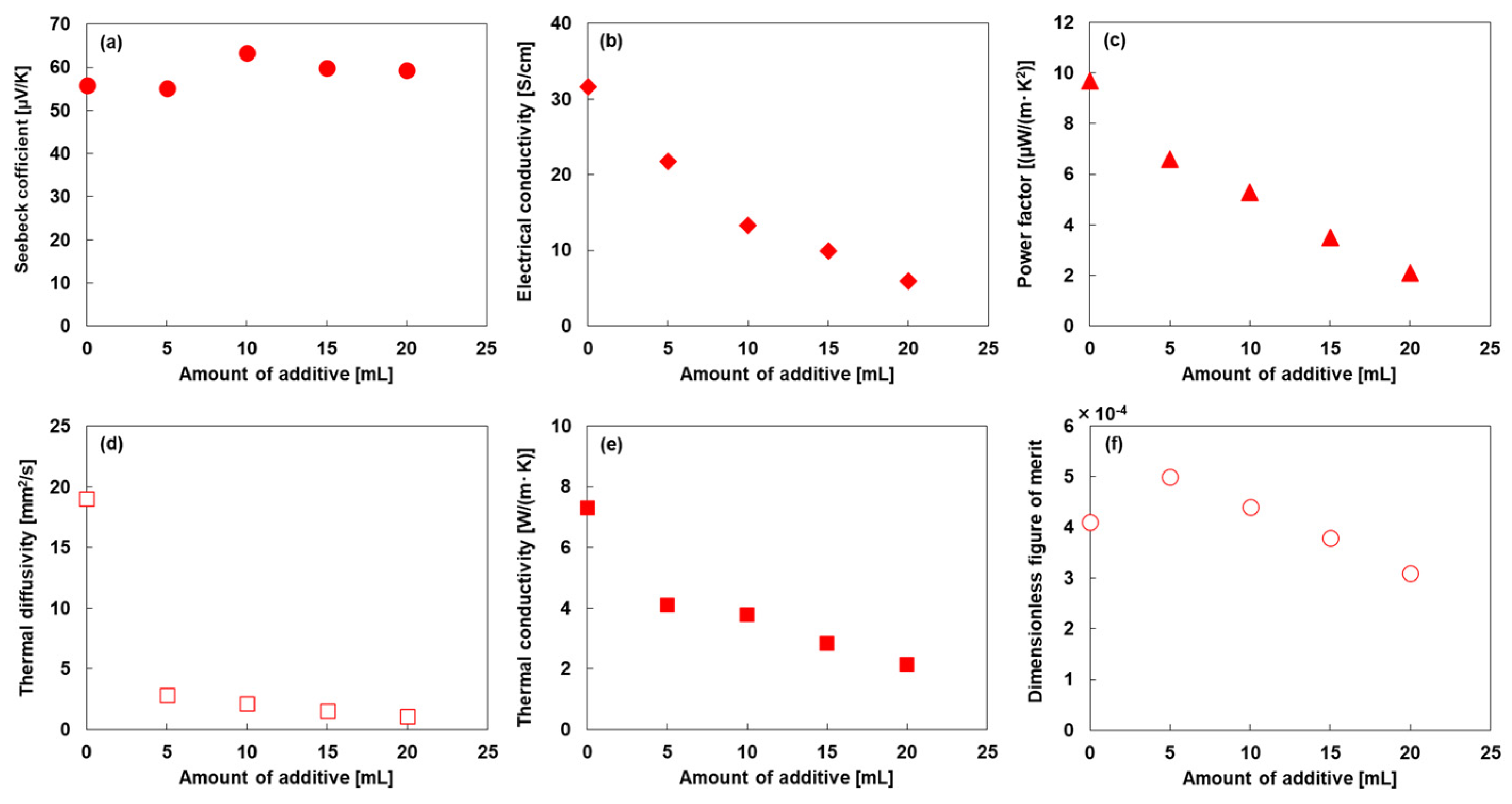

3.2. Thermoelectric Properties of SWCNT-Based Composite Films

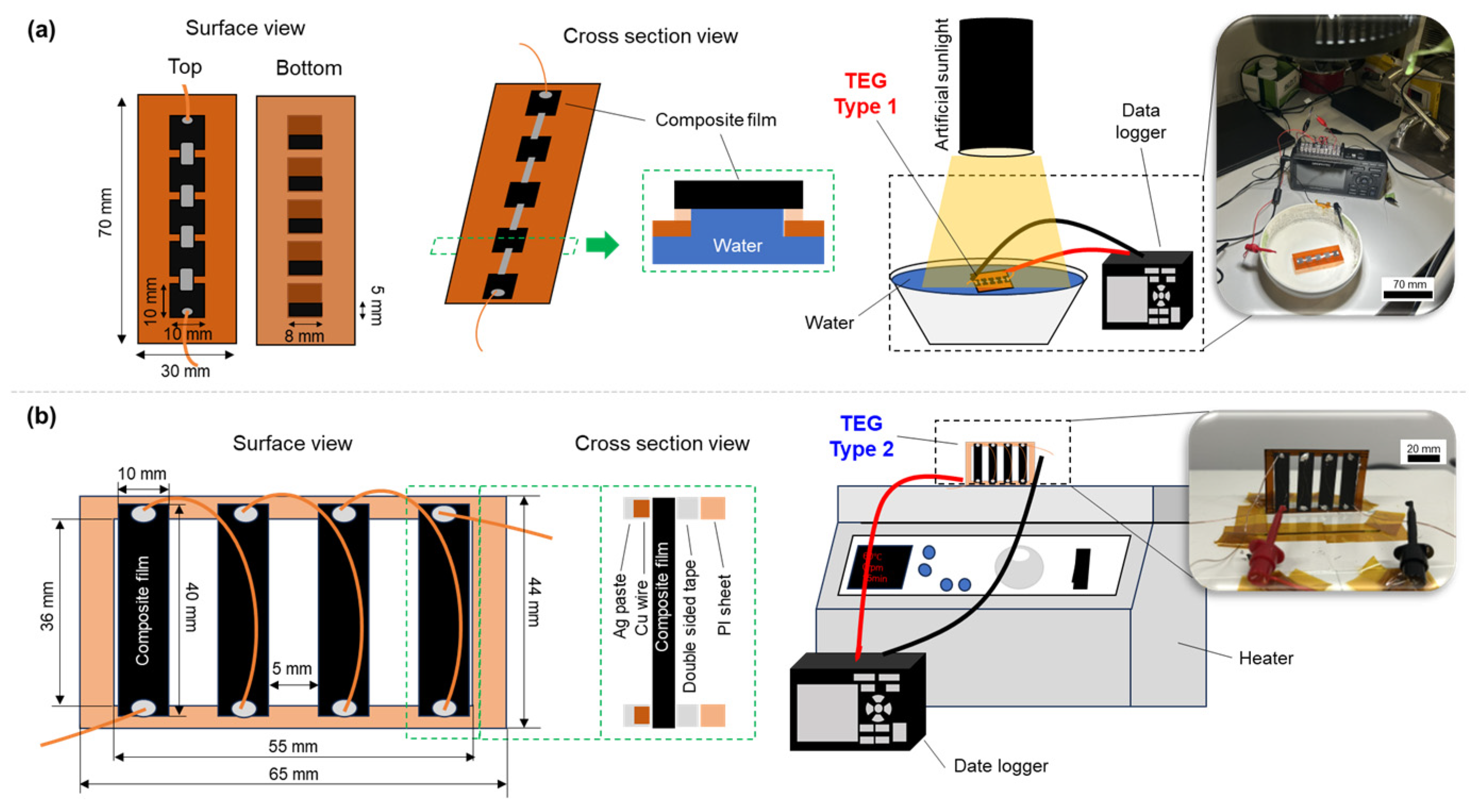

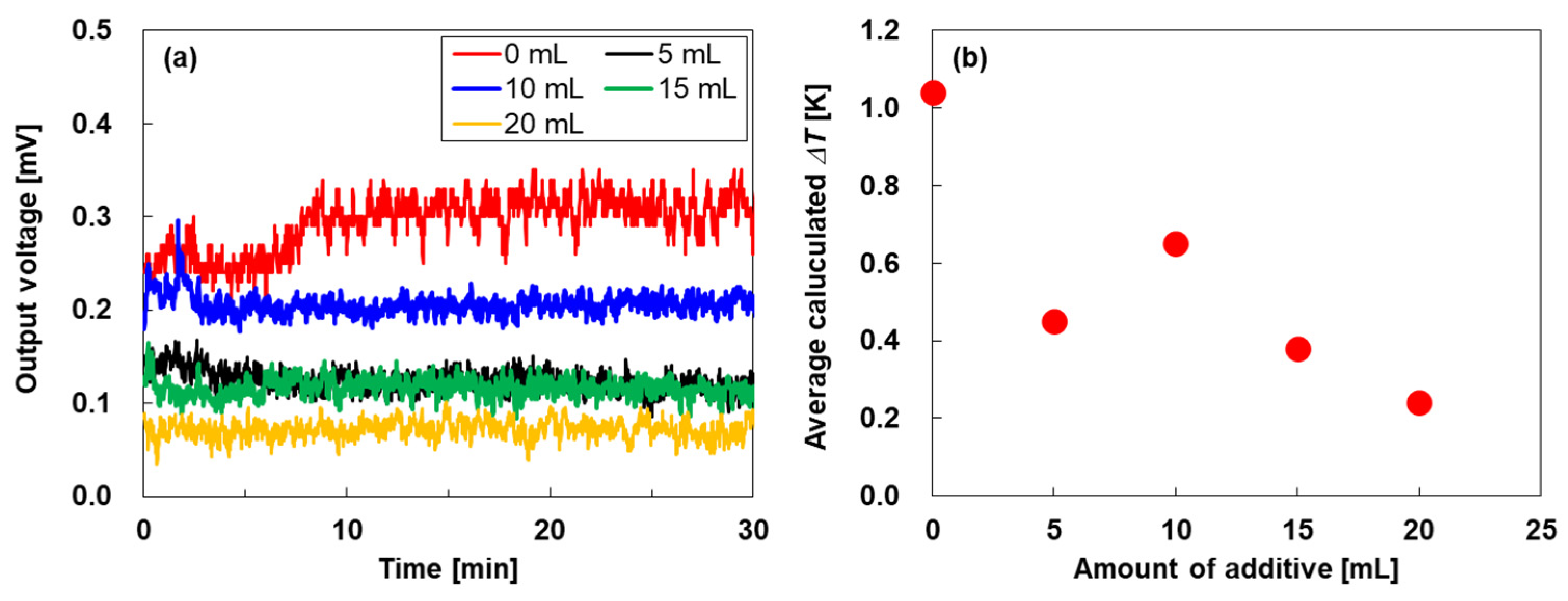

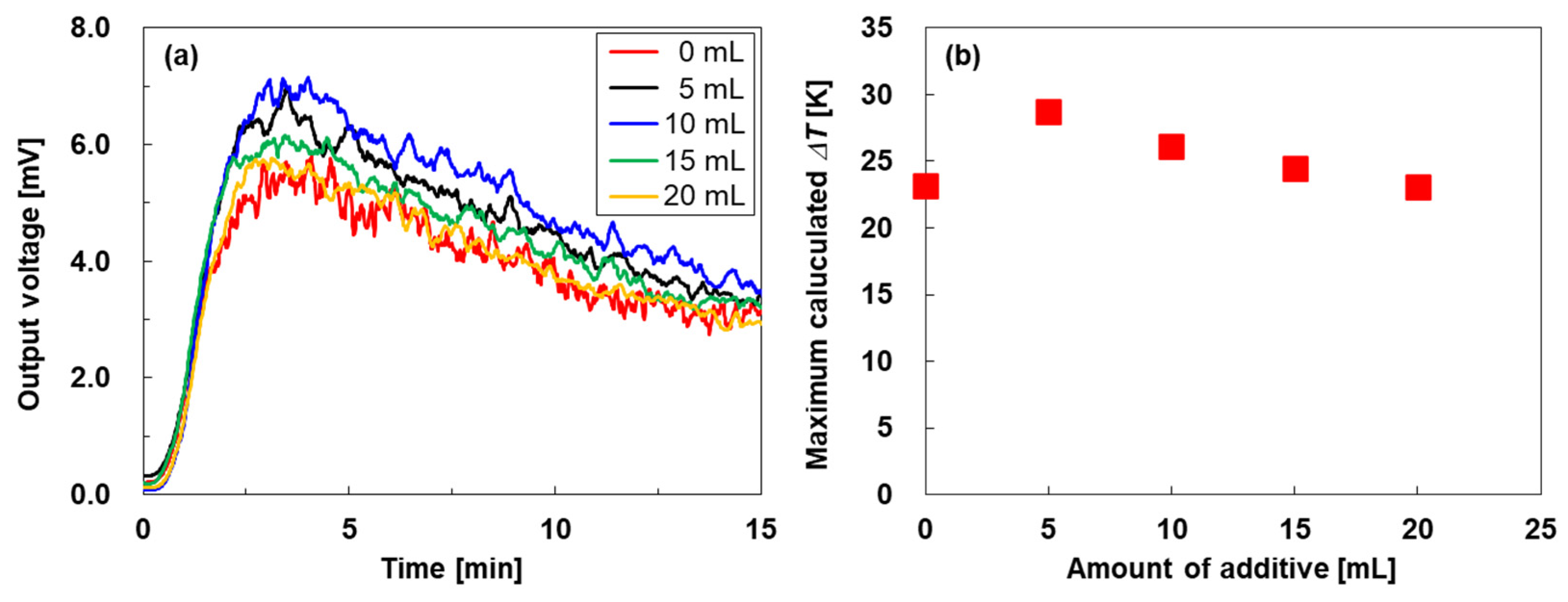

3.3. Performance of TEGs Using SWCNT-Based Composite Films

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Micko, K.; Papcun, P.; Zolotova, I. Review of IoT sensor systems used for monitoring the road infrastructure. Sensors 2023, 23, 4469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, S.F.; Alam, M.S.B.; Hoque, M.; Lameesa, A.; Afrin, S.; Farah, T.; Kabir, M.; Shafiullah, G.M.; Muyeen, S.M. Industrial Internet of Things enabled technologies, challenges, and future directions. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2023, 110, 108847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Yu, F.R.; Deng, G.; Luo, C.; Ming, Z.; Yan, Q. Industrial internet: A survey on the enabling technologies, applications, and challenges. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials 2017, 19, 1504–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakopoulos, D.; Jayaraman, P.P. Internet of things: From internet scale sensing to smart services. Computing 2016, 98, 1041–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.D.; He, W.; Li, S. Internet of Things in industries: A survey. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2014, 10, 6945918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zeng, Y.; Chen, X.; Fan, Y. The internet of things in healthcare: An overview. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2016, 1, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-kahtani, M.S.; Khan, F.; Taekeun, W. Application of Internet of Things and sensors in healthcare. Sensors 2022, 22, 5738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzounis, A.; Katsoulas, N.; Bartzanas, T.; Kittas, C. Internet of Things in agriculture, recent advances and future challenges. Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 164, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kour, V.P.; Arora, S. Recent developments of the Internet of Things in agriculture: A survey. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 129924–129957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaqoob, I.; Ahmed, E.; Hashem, I.A.T.; Ahmed, A.I.A.; Gani, A.; Imran, M. Internet of Things architecture: Recent advances, taxonomy, requirements, and open challenges. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2017, 24, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsharif, M.H.; Jahid, A.; Kelechi, A.H.; Kannadasan, R. Green IoT: A review and future research directions. Symmetry 2023, 15, 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, H.; Yang, Q. EcoSense: A hardware approach to on-demand sensing in the Internet of Things. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2016, 54, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Huang, L.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z. Harvesting ambient environmental energy for wireless sensor networks: A survey. J. Sens. 2014, 2014, 815467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matiko, J.W.; Grabham, N.J.; Beeby, S.P.; Tudor, M.J. Review of the application of energy harvesting in buildings. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2014, 25, 012002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanislav, T.; Mois, G.D.; Zeadally, S.; Folea, S.C. Energy harvesting techniques for internet of things (IoT). IEEE Access 2021, 9, 39530–39549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prauzek, M.; Konecny, J.; Borova, M.; Janosova, K.; Hlavica, J.; Musílek, P. Energy harvesting sources, storage devices and system topologies for environmental wireless sensor networks: A Review. Sensors 2018, 18, 2446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Radousky, H.B.; Liang, H. Energy harvesting: An integrated view of materials, devices and applications. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 502001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, O.H., Jr.; Maran, A.L.O.; Henao, N.C. A review of the development and applications of thermoelectric microgenerators for energy harvesting. Renew. Sust. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massetti, M.; Jiao, F.; Ferguson, A.J.; Zhao, D.; Wijeratne, K.; Würger, A.; Blackburn, J.L.; Crispin, X.; Fabiano, S. Unconventional thermoelectric materials for energy harvesting and sensing applications. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 12465–12547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, J.P.; Gonçalves, L.M.; Correia, J.H. Thermoelectric microconverter for energy harvesting systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2010, 57, 861–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Xin, H.; Qin, X.; Zhang, J.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Song, C.; Li, C. Enhanced thermoelectric performance of highly oriented polycrystalline SnSe based composites incorporated with SnTe nanoinclusions. J. Alloys Compd. 2016, 689, 445–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumoto, K.; Funahashi, R.; Guilmeau, E.; Miyazaki, Y.; Weidenkaff, A.; Wang, Y.; Wan, C. Thermoelectric ceramics for energy harvesting. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2013, 96, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebald, G.; Guyomar, D.; Agbossou, A. On thermoelectric and pyroelectric energy harvesting. Smart Mater. Struct. 2009, 18, 125006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonov, V. Thermoelectric energy harvesting of human body heat for wearable sensors. IEEE Sens. J. 2013, 13, 2284–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Qian, X.; Han, C.G.; Li, Q.; Chen, G. Ionic thermoelectric materials for near ambient temperature energy harvesting. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 020501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagiwa, Y.; Shinohara, Y. A practical appraisal of thermoelectric materials for use in an autonomous power supply. Scripta Mater. 2019, 172, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Funahashi, R.; Matsubara, I.; Ueno, K.; Sodeoka, S.; Yamada, H. Synthesis and thermoelectric properties of the new oxide materials Ca3-xBixCo4O9+δ (0.0 < x < 0.75). Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 2424–2427. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán-Pitarch, B.; Vidan, F.; Carbó, M.; García-Cañadas, J. Impedance spectroscopy analysis of thermoelectric modules under actual energy harvesting operating conditions and a small temperature difference. Appl. Energy 2024, 364, 123281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norimasa, O.; Tamai, R.; Nakayama, H.; Shinozaki, Y.; Takashiri, M. Self-generated temperature gradient under uniform heating in p–i–n junction carbon nanotube thermoelectric generators. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 15956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, S.; Ichihashi, T. Single-shell carbon nanotubes of 1-nm diameter. Nature 1993, 363, 603–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshima, K.; Yanagawa, Y.; Asano, H.; Shiraishi, Y.; Toshima, N. Improvement of stability of n-type super growth CNTs by hybridization with polymer for organic hybrid thermoelectrics. Synth. Met. 2017, 225, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, N.; Ichinose, Y.; Dewey, O.S.; Taylor, L.W.; Trafford, M.A.; Yomogida, Y.; Wehmeyer, G.; Pasquali, M.; Yanagi, K.; Kono, J. Macroscopic weavable fibers of carbon nanotubes with giant thermoelectric power factor. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonoguchi, Y.; Nakano, M.; Murayama, T.; Hagino, H.; Hama, S.; Miyazaki, K.; Matsubara, R.; Nakamura, M.; Kawai, T. Simple salt-coordinated n-type nanocarbon materials stable in air. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 3021–3028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avery, A.D.; Zhou, B.H.; Lee, J.; Lee, E.; Miller, E.M.; Ihly, R.; Wesenberg, D.; Mistry, K.S.; Guillot, S.L.; Zink, B.L.; et al. Tailored semiconducting carbon nanotube networks with enhanced thermoelectric properties. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seki, Y.; Nagata, K.; Takashiri, M. Facile preparation of air-stable n-type thermoelectric single-wall carbon nanotube films with anionic surfactants. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 8104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yonezawa, S.; Chiba, T.; Seki, Y.; Takashiri, M. Origin of n type properties in single wall carbon nanotube films with anionic surfactants investigated by experimental and theoretical analyses. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 5758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, D.A.; Ericson, L.M.; Casavant, M.J.; Liu, J.; Colbert, D.T.; Smith, K.A.; Smalley, R.E. Elastic strain of freely suspended single-wall carbon nanotube ropes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1999, 74, 3803–3805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; Files, B.S.; Arepalli, S.; Ruoff, R.S. Tensile loading of ropes of single wall carbon nanotubes and their mechanical properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 84, 5552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Cheng, H.M.; Bai, S.; Su, G.; Dresselhaus, M.S. Tensile strength of single-walled carbon nanotubes directly measured from their macroscopic ropes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2000, 77, 3161–3163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhbanov, A.I.; Pogorelov, E.G.; Chang, Y.-C. Van der Waals interaction between two crossed carbon nanotubes. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 5937–5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Chou, T.-W. Elastic moduli of multi-walled carbon nanotubes and the effect of van der Waals forces. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2003, 63, 1517–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatasubramanian, R.; Siivola, E.; Colpitts, T.; O’Quinn, B. Thin-film thermoelectric devices with high room-temperature figures of merit. Nature 2001, 413, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, B.; Hao, Q.; Ma, Y.; Lan, Y.; Minnich, A.; Yu, B.; Yan, X.; Wang, D.; Muto, A.; Vashaee, D.; et al. High-thermoelectric performance of nanostructured Bismuth antimony Telluride bulk alloys. Science 2008, 320, 5876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, J.; Yang, L.; Ma, Z.; Song, P.; Zhang, M.; Ma, J.; Yang, F.; Wang, X. Review of current high-ZT thermoelectric materials. J. Mater. Sci. 2020, 55, 12642–12704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, K.; Hagino, H.; Miyazaki, K. Fabrication of Bismuth Telluride thermoelectric films containing conductive polymers using a printing method. J. Electron. Mater. 2013, 42, 1313–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amma, Y.; Miura, K.; Nagata, S.; Nishi, T.; Miyake, S.; Miyazaki, K.; Takashiri, M. Ultra-long air-stability of n-type carbon nanotube films with low thermal conductivity and all-carbon thermoelectric generators. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Yabuki, H.; Takashiri, M. High thermoelectric performance of flexible nanocomposite films based on Bi2Te3 nanoplates and carbon nanotubes selected using ultracentrifugation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, S.; Hagino, H.; Tanaka, S.; Miyazaki, K.; Takashiri, M. Determining the thermal conductivities of nanocrystalline bismuth telluride thin films using the differential 3ω method while accounting for thermal contact resistance. J. Electron. Mater. 2015, 44, 2021–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blackburn, J.L.; Ferguson, A.J.; Cho, C.; Grunlan, J.C. Carbon-nanotube-based thermoelectric materials and devices. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1704386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Shi, X.-L.; Li, L.; Liu, Q.; Hu, B.; Chen, W.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q.; Chen, Z.-G. Advances and outlooks for carbon nanotube-based thermoelectric materials and devices. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2500947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Liu, C.; Fan, S. A promising approach to enhanced thermoelectric properties using carbon nanotube networks. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wu, D.; Liu, C.; Zhong, F.; Cao, G.; Li, B.; Gao, C.; Wang, L. Free-standing p-Type SWCNT/MXene composite films with low thermal conductivity and enhanced thermoelectric performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 439, 135706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S.; Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Deng, L.; Chen, G. SWCNT network evolution of PEDOT: PSS/SWCNT composites for thermoelectric application. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 428, 131137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLeod, B.A.; Stanton, N.J.; Gould, I.E.; Wesenberg, D.; Ihly, R.; Owczarczyk, Z.R.; Hurst, K.E.; Fewox, C.S.; Folmar, C.N.; Hughes, K.H.; et al. Large n- and p-type thermoelectric power factors from doped semiconducting single-walled carbon nanotube thin films. Energy Environ. Sci. 2017, 10, 2168–2179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Shang, Y.; Chang, S.; Dai, L.; Cao, A. Application-driven carbon nanotube functional materials. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 7946–7974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, J.; Song, H.; Pan, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Yao, Y.; Huang, F.; Zuo, C. High performance polypyrrole/SWCNTs composite film as a promising organic thermoelectric material. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 17704–17709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z.; Wang, G.; Wolan, B.F.; Wu, N.; Wang, C.; Zhao, S.; Yue, S.; Li, B.; He, W.; Liu, J.; et al. Printable aligned single-walled carbon nanotube film with outstanding thermal conductivity and electromagnetic interference shielding performance. Nano Micro Lett. 2022, 14, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, Y.; Sekiguchi, A.; Kobashi, K.; Sundaram, R.; Yamada, T.; Hata, K. Mechanically robust free-standing single-walled carbon nanotube thin films with uniform mesh-structure by blade coating. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 562455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiba, T.; Amma, Y.; Takashiri, M. Heat source free water floating carbon nanotube thermoelectric generators. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 14707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakazawa, Y.; Yamamoto, H.; Okano, Y.; Amezawa, T.; Kuwahata, H.; Miyake, S.; Takashiri, M. Boosting performance of heat-source free water-floating thermoelectric generators by controlling wettability by mixing single-walled carbon nanotubes with α-cellulose. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 258, 124714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miura, K.; Amezawa, T.; Tanaka, S.; Takashiri, M. Improved heat dissipation of dip-coated SWCNT/mesh sheets with high flexibility and free-standing strength for thermoelectric generators. Coatings 2024, 14, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Amezawa, T.; Okano, Y.; Hoshino, K.; Ochiai, S.; Sunaga, K.; Miyake, S.; Takashiri, M. High thermal durability and thermoelectric performance with ultra-low thermal conductivity in n-type single-walled carbon nanotube films by controlling dopant concentration with cationic surfactant. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 126, 063902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Huang, J.; Zhu, F.; Wang, Y.; Shao, Y.; Li, X.; Zhou, Y.; Song, L. Study on energy storage performance of thermally enhanced composite phase change material of calcium nitrate tetrahydrate. J. Energy Storage 2022, 52, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singkaselit, K.; Sakulkalavek, A.; Sakdanuphab, R. Effects of Annealing temperature on the structural, mechanical and electrical properties of flexible bismuth telluride thin films prepared by high-pressure RF magnetron sputtering. Adv. Nat. Sci. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2017, 8, 035002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.-H.; Fan, P.; Liang, G.-X.; Zhang, D.-P.; Cai, X.-M.; Chen, T.-B. Annealing temperature influence on electrical properties of ion beam sputtered Bi2Te3 thin films. J. Phys. Chem. Solids 2010, 71, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundstrom, M. Fundamentals of Carrier Transport, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2000; pp. 158–211. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Fina, A. Thermal conductivity of carbon nanotubes and their polymer nanocomposites: A Review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2011, 36, 914–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakazawa, Y.; Shinozaki, Y.; Nakayama, H.; Ochiai, S.; Miyake, S.; Takashiri, M. SWCNT-Based Composite Films with High Mechanical Strength and Stretchability by Combining Inorganic-Blended Acrylic Emulsion for Various Thermoelectric Generators. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231817

Nakazawa Y, Shinozaki Y, Nakayama H, Ochiai S, Miyake S, Takashiri M. SWCNT-Based Composite Films with High Mechanical Strength and Stretchability by Combining Inorganic-Blended Acrylic Emulsion for Various Thermoelectric Generators. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(23):1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231817

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakazawa, Yuto, Yoshiyuki Shinozaki, Hiroto Nakayama, Shuya Ochiai, Shugo Miyake, and Masayuki Takashiri. 2025. "SWCNT-Based Composite Films with High Mechanical Strength and Stretchability by Combining Inorganic-Blended Acrylic Emulsion for Various Thermoelectric Generators" Nanomaterials 15, no. 23: 1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231817

APA StyleNakazawa, Y., Shinozaki, Y., Nakayama, H., Ochiai, S., Miyake, S., & Takashiri, M. (2025). SWCNT-Based Composite Films with High Mechanical Strength and Stretchability by Combining Inorganic-Blended Acrylic Emulsion for Various Thermoelectric Generators. Nanomaterials, 15(23), 1817. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15231817