Phase-Selective Synthesis of Anatase and Rutile TiO2 Nanocrystals and Their Impacts on Grapevine Leaves: Accumulation of Mineral Nutrients and Triggering the Plant Defense

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis

2.2.1. Synthesis of Anatase Nanocrystals

2.2.2. Synthesis of Rutile Nanocrystals

2.3. Experimental Site and Plant Material

2.4. Leaf Treatment

2.5. Extraction of Leaves for High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

2.6. Methods

2.7. Statistics

3. Results

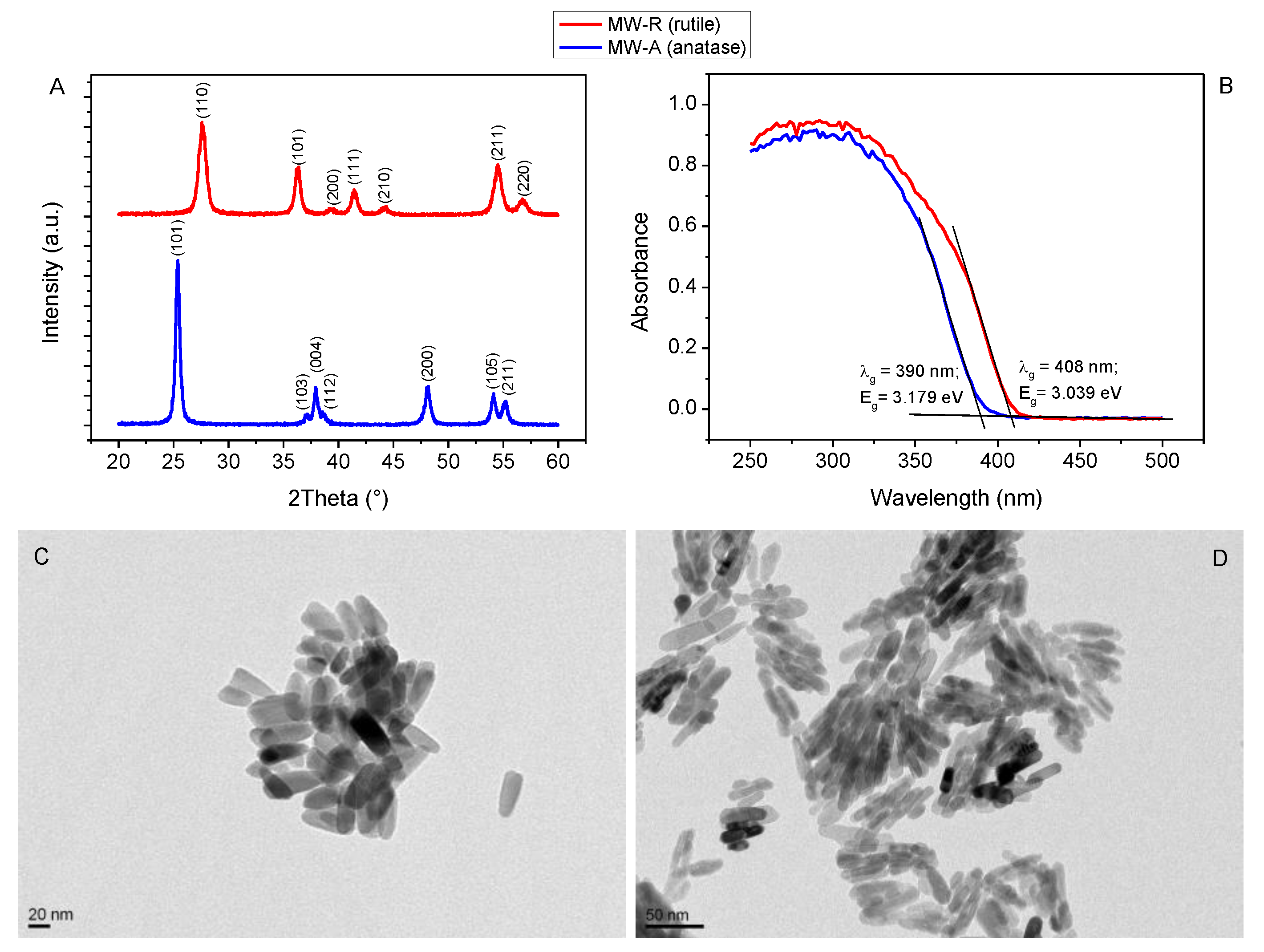

3.1. Structural, Optical and Morphological Properties of Anatase and Rutile TiO2 NCs

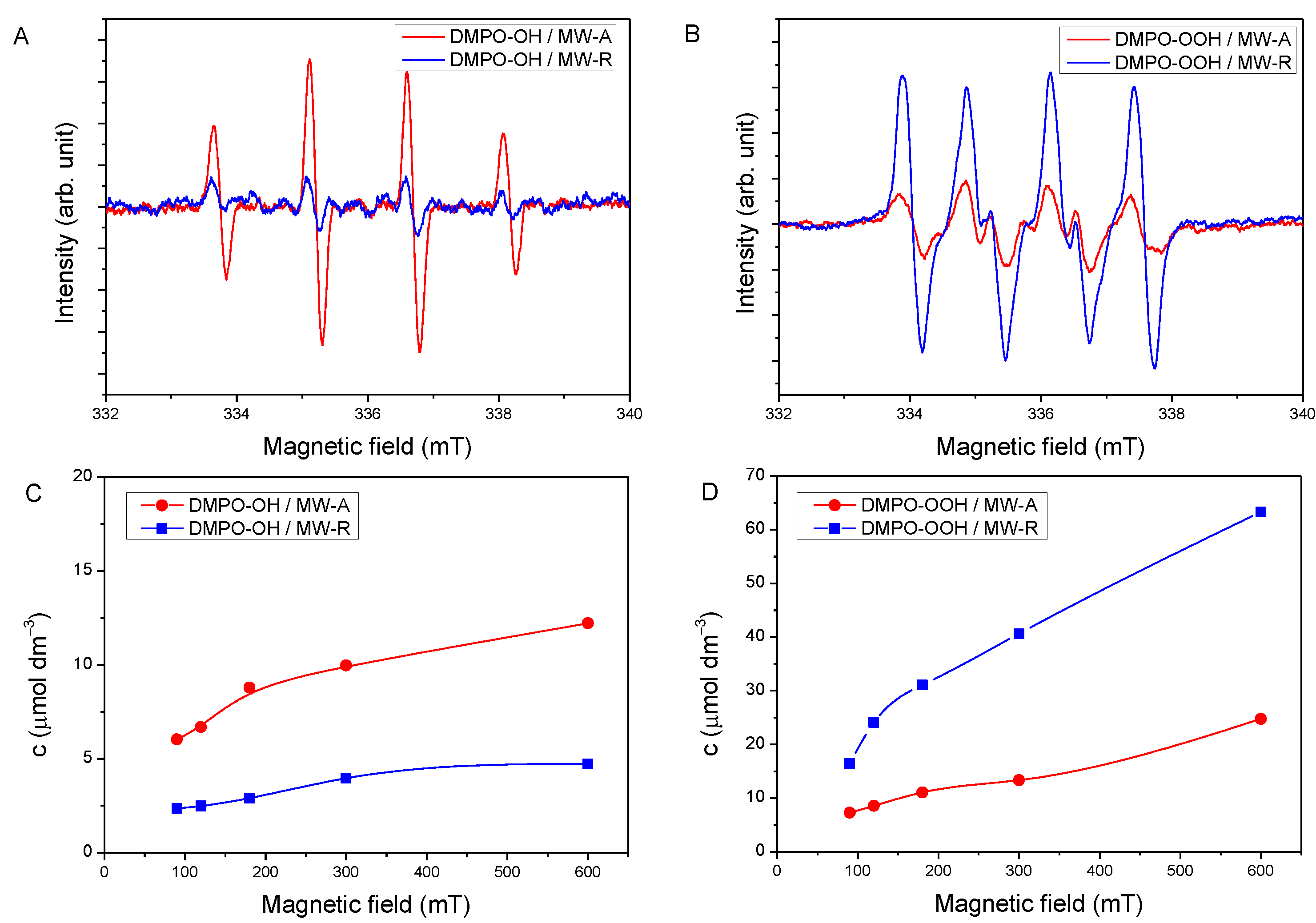

3.2. Crystal Phase-Dependent Formation of Reactive Oxygen Species

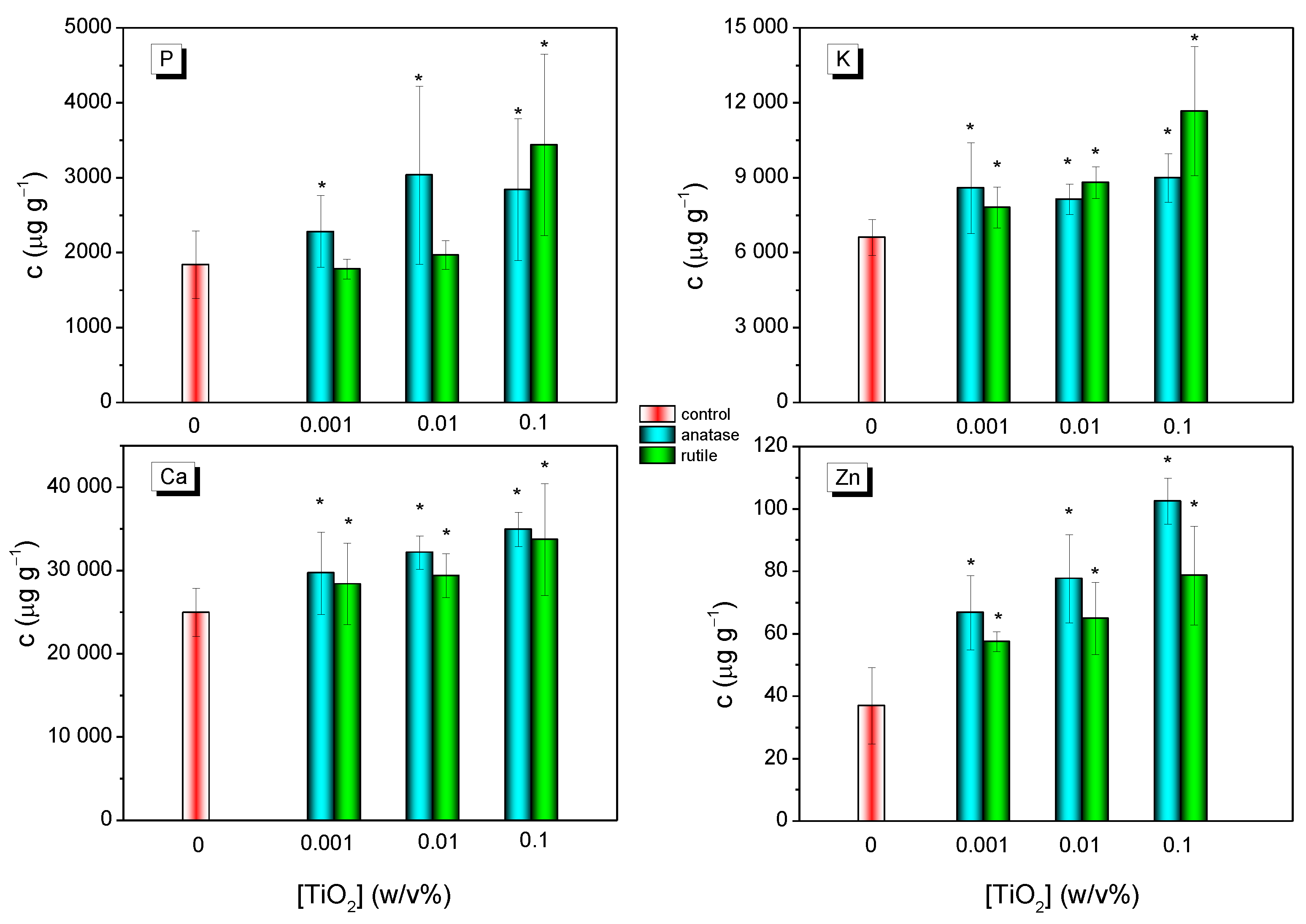

3.3. Changes of the Level of Mineral Nutrients in Grapevine Leaves Induced by Anatase and Rutile TiO2 NCs

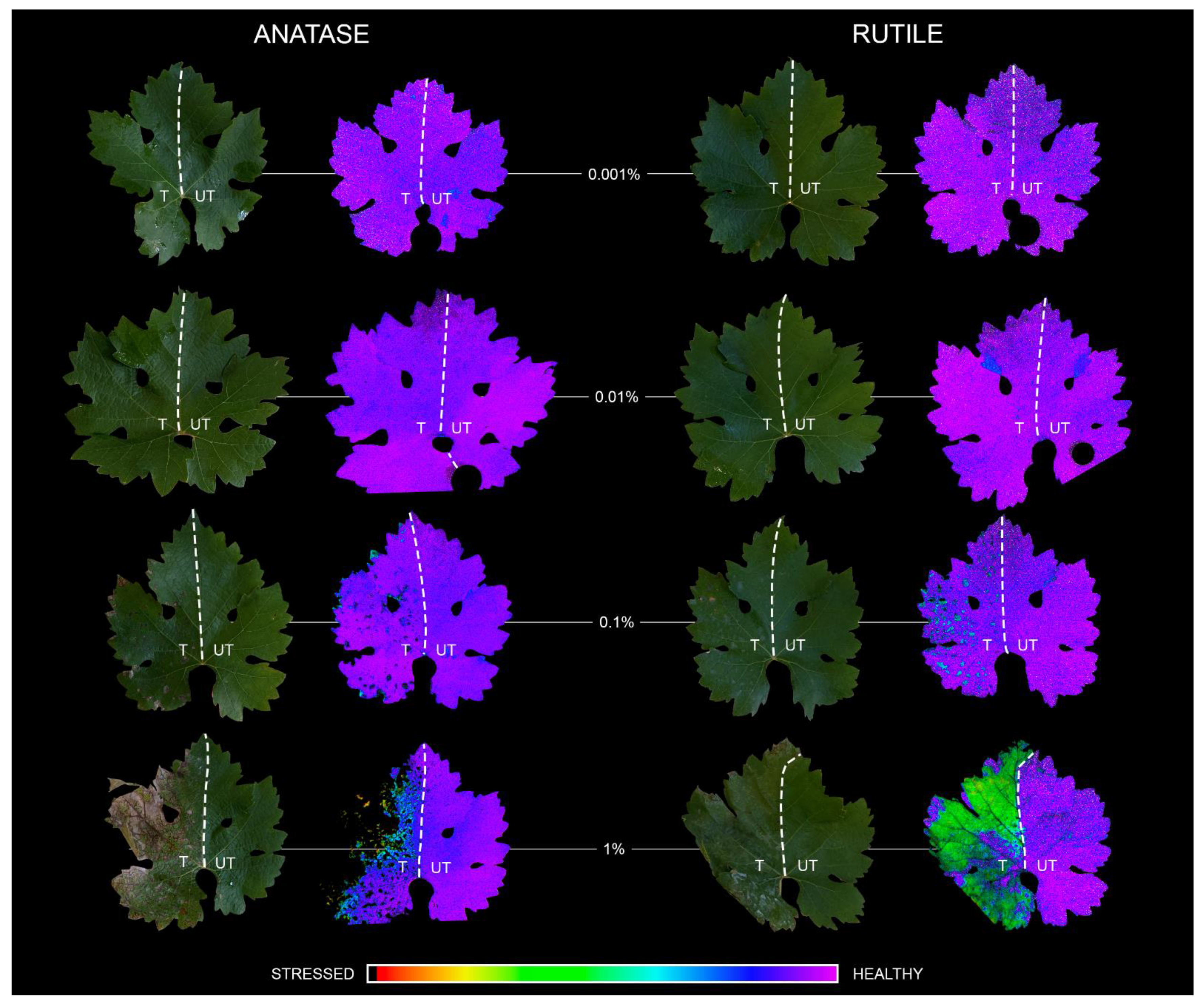

3.4. Dose-Dependent Phytotoxicity of Anatase and Rutile TiO2 NCs

3.5. Anatase and Rutile TiO2 NCs Triggered the Antioxidant Defense System Enhancing the Level of Vitamin B6 in Grapevine Leaves

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Thomas, S.; Grohens, Y.; Pottathara, Y.B. (Eds.) Industrial Applications of Nanomaterials; Imprint Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; ISBN 978-0-12-815749-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikaeen, G.; Abbaszadeh, S.; Yousefineja, S. Application of nanomaterials in treatment, anti-infection and detection of coronaviruses. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 1501–1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Mahendra, S.; Alvarez, P.J.J. Nanomaterials in the Construction Industry: A Review of Their Applications and Environmental Health and Safety Considerations. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 3580–3590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, Y.; Liu, S.; Yi, Y.; Rong, H.; Zhang, J. Catalytic Nanomaterials toward Atomic Levels for Biomedical Applications: From Metal Clusters to Single-Atom Catalysts. ACS Nano 2021, 15, 2005–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avellan, A.; Yun, J.; Morais, B.P.; Clement, E.T.; Rodrigues, S.M.; Lowry, G.V. Critical Review: Role of Inorganic Nanoparticle Properties on Their Foliar Uptake and in Planta Translocation. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 13417–13431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhu, S.; Gu, Z.; Chen, C.; Zhao, Y. Toxicity of manufactured nanomaterials. Particuology 2021, 69, 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, P.; Breen, A.; Pillai, S.C. Toxicity of Nanomaterials: Exposure, Pathways, Assessment, and Recent Advances. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 2237–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrino, F.; Palmisano, L. (Eds.) Titanium Dioxide (TiO2) and Its Applications; Elsevier Science: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; ISBN 978-0-12-819960-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carp, O.; Huisman, C.L.; Reller, A. Photoinduced reactivity of titanium dioxide. Prog. Solid State Chem. 2004, 32, 33–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, H.; Moon, G.; Choi, W. Photoinduced charge transfer processes in solar photocatalysis based on modified TiO2. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 411–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hanaor, D.A.H.; Sorrell, C.C. Review of the anatase to rutile phase transformation. J. Mater. Sci. 2011, 46, 855–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, H.; Banfield, J.F. Structural Characteristics and Mechanical and Thermodynamic Properties of Nanocrystalline TiO2. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 9613–9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luttrell, T.; Halpegamage, S.; Tao, J.; Kramer, A.; Sutter, E.; Batzill, M. Why is anatase a better photocatalyst than rutile?—Model studies on epitaxial TiO2 films. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Uddin, M.J.; Cesano, F.; Chowdhury, A.R.; Trad, T.; Cravanzola, S.; Martra, G.; Mino, L.; Zecchina, A.; Scarano, D. Surface Structure and Phase Composition of TiO2 P25 Particles After Thermal Treatments and HF Etching. Front. Mater. 2020, 7, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Martinez, A.; Koop-Santa, C.; Ceballos-Sanchez, O.; López-Mena, E.R.; González, M.A.; Rangel-Cobián, V.; Orozco-Guareño, E.; García-Guaderrama, M. Study of the preparation of TiO2 powder by different synthesis methods. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 085085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhou, Z.; Hicks, A.L. Life Cycle Impact of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticle Synthesis through Physical, Chemical, and Biological Routes. Envir. Sci. Tech. 2019, 53, 4078–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamaghani, A.H.; Haghighat, F.; Lee, C.-S. Hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis and treatment of TiO2 for photocatalytic degradation of air pollutants: Preparation, characterization, properties, and performance. Chemosphere 2019, 219, 804–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, T.; Qian, R.; Tang, Y.; Yang, J.; Dai, Y.; Lee, W.I.; Pan, J.H. Controllable Synthesis and Crystallization of Nanoporous TiO2 Deep-Submicrospheres and Nanospheres via an Organic Acid-Mediated Sol−Gel Process. Langmuir 2020, 36, 7447–7455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gogos, A.; Knauer, K.; Bucheli, T.D. Nanomaterials in Plant Protection and Fertilization: Current State, Foreseen Applications, and Research Priorities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 9781–9792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Lu, L.; Wang, A.; Zhang, H.; Huang, M.; Wu, H.; Xing, B.; Wang, Z.; Ji, R. Nano-Biotechnology in Agriculture: Use of Nanomaterials to Promote Plant Growth and Stress Tolerance. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2020, 68, 1935–1947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šebesta, M.; Kolenčík, M.; Sunil, B.R.; Illa, R.; Mosnáček, J.; Ingle, A.P.; Urík, M. Field Application of ZnO and TiO2 Nanoparticles on Agricultural Plants. Agronomy 2021, 11, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kah, M.; Kookana, R.S.; Gogos, A.; Bucheli, T.D. A critical evaluation of nanopesticides and nanofertilizers against their conventional analogues. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018, 13, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jogaiah, S.; Singh, H.; Fraceto, L.F.; Lima, R. (Eds.) Advances in Nano-Fertilizers and Nano-Pesticides in Agriculture. A Smart Delivery System for Crop Improvement, 1st ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2021; ISBN 978-0-12-820092-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Gusain, D.; Sharma, Y.C. Critical Review on the Toxicity of Some Widely Used Engineered Nanoparticles. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015, 54, 6209–6233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J.; Zhao, L.; Wu, J.; Xiong, H.; Bao, Y.; Zeb, A.; Tang, J.; Liu, W. Foliar spray of TiO2 nanoparticles prevails over root application in reducing Cd accumulation and mitigating Cd-induced phytotoxicity in maize (Zea mays L.). Chemosphere 2020, 239, 124794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gordillo-Delgado, F.; Zuluaga-Acosta, J.; Restrepo-Guerrero, G. Effect of the suspension of Ag-incorporated TiO2 nanoparticles (Ag-TiO2 NPs) on certain growth, physiology and phytotoxicity parameters in spinach seedlings. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0244511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Naeem, M.S.; Wang, X.; Liu, L.; Chen, C.; Ma, N.; Zhang, C. Nano-TiO2 Is Not Phytotoxic As Revealed by the Oilseed Rape Growth and Photosynthetic Apparatus Ultra-Structural Response. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0143885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szőllősi, R.; Molnár, Á.; Kondak, S.; Kolbert, Z. Dual Effect of Nanomaterials on Germination and Seedling Growth: Stimulation vs. Phytotoxicity. Plants 2020, 9, 1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, S.; Oliveira, H.; Silva, A.M.S.; Santos, C. The cytotoxic targets of anatase or rutile + anatase nanoparticles depend on the plant species. Biol. Plantarum 2017, 61, 717–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larue, C.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Sobanska, S.; Trcera, N.; Sorieul, S.; Cécillon, L.; Ouerdane, L.; Legros, S.; Sarret, G. Fate of pristine TiO2 nanoparticles and aged paint-containing TiO2 nanoparticles in lettuce crop after foliar exposure. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 273, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahardoli, A.; Sharifan, H.; Karimi, N.; Kakavand, S.N. Uptake, translocation, phytotoxicity, and hormetic effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles (TiO2 NPs) in Nigella arvensis L. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.; Wang, W.; Sun, J.; Zhu, L. Photosynthesis and related metabolic mechanism of promoted rice (Oryza sativa L.) growth by TiO2 nanoparticles. Front. Environ. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhou, P.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. New understanding of the difference of photocatalytic activity among anatase, rutile and brookite TiO2. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 20382–20386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, B.; Cui, H.; An, H.; Pan, Y.; Zhai, J. Synthesis of Crystal-Controlled TiO2 Nanorods by a Hydrothermal Method: Rutile and Brookite as Highly Active Photocatalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 16905–16912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kőrösi, L.; Bouderias, S.; Csepregi, K.; Bognár, B.; Teszlák, P.; Scarpellini, A.; Castelli, A.; Hideg, É.; Jakab, G. Nanostructured TiO2-induced photocatalytic stress enhances the antioxidant capacity and phenolic content in the leaves of Vitis vinifera on a genotype-dependent manner. J. Photoch. Photobio. B 2019, 190, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kőrösi, L.; Pertics, B.; Schneider, G.; Bognár, B.; Kovács, J.; Meynen, V.; Scarpellini, A.; Pasquale, L.; Prato, M. Photocatalytic Inactivation of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria Using TiO2 Nanoparticles Prepared Hydrothermally. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schreiber, U. Pulse-Amplitude-Modulation (PAM) Fluorometry and Saturation Pulse Method: An Overview. In Chlorophyll a Fluorescence. Advances in Photosynthesis and Respiration; Papageorgiou, G.C., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2004; Volume 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holzwarth, U.; Gibson, N. The Scherrer equation versus the ‘Debye-Scherrer equation’. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Prasad, K.; Sanjinès, R.; Schmid, P.E.; Lévy, F. Electrical and optical properties of TiO2 anatase thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 1994, 75, 2042–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsega, M.; Dejene, F.B. Influence of acidic pH on the formulation of TiO2 nanocrystalline powders with enhanced photoluminescence property. Heliyon 2017, 3, e00246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kotsyubynsky, V.O.; Myronyuk, I.F.; Myronyuk, L.I.; Chelyadyn, V.L.; Mizilevska, M.H.; Hrubiak, A.B.; Tadeush, O.K.; Nizamutdinov, F.M. The effect of pH on the nucleation of titania by hydrolysis of TiCl4. Mat. Wiss. Werkst. 2016, 47, 288–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittingham, M.S. Hydrothermal synthesis of transition metal oxides under mild conditions. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 1996, 1, 227–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Z.; Lu, G.Q.; Greenfield, P.F. Role of the Crystallite Phase of TiO2 in Heterogeneous Photocatalysis for Phenol Oxidation in Water. J. Phys. Chem. B 2000, 104, 4815–4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Godiksen, A.L.; Mamahkel, A.; Søndergaard-Pedersen, F.; Rios-Carvajal, T.; Marks, M.; Lock, N.; Rasmussen, S.B.; Iversen, B.B. Selective. Catalytic Reduction of NO Using Phase-Pure Anatase, Rutile, and Brookite TiO2 Nanocrystals. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 15324–15334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Li, Y.; Shen, W. Tuning the shape and crystal phase of TiO2 nanoparticles for catalysis. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 6838–6850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allende-González, P.; Laguna-Bercero, M.Á.; Barrientos, L.; Valenzuela, M.L.; Díaz, C. Solid State Tuning of TiO2 Morphology, Crystal Phase, and Size through Metal Macromolecular Complexes and Its Significance in the Photocatalytic Response. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 3159–3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.-C.; Ying, J.Y. Sol−Gel Synthesis and Hydrothermal Processing of Anatase and Rutile Titania Nanocrystals. Chem. Mater. 1999, 11, 3113–3120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, N.T.; Seery, M.K.; Pillai, S.C. Spectroscopic Investigation of the Anatase-to-Rutile Transformation of Sol−Gel-Synthesized TiO2 Photocatalysts. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 16151–16157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetchakun, N.; Incessungvorn, B.; Wetchakun, K.; Phanichphant, S. Influence of calcination temperature on anatase to rutile phase transformation in TiO2 nanoparticles synthesized by the modified sol–gel method. Mater. Lett. 2012, 82, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.G.; Kang, J.M.; Lee, J.E.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, K.H.; Cho, M.; Lee, S.G. Effects of Calcination Temperature on the Phase Composition, Photocatalytic Degradation, and Virucidal Activities of TiO2 Nanoparticles. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 10668–10678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Olds, D.; Peng, R.; Yu, L.; Foo, G.S.; Qian, S.; Keum, J.; Guiton, B.S.; Wu, Z.; Page, K. Quantitative Analysis of the Morphology of {101} and {001} Faceted Anatase TiO2 Nanocrystals and Its Implication on Photocatalytic Activity. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 5591–5604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhang, P.; Guo, L.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Q.; Ding, Y.; Zheng, W.; Cao, Y. The Design of TiO2 Nanostructures (Nanoparticle, Nanotube, and Nanosheet) and Their Photocatalytic Activity. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 12727–12733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Reunchan, P.; Ouyang, S.; Tong, H.; Umezawa, N.; Kako, T.; Ye, J. Anatase TiO2 Single Crystals Exposed with High-Reactive {111} Facets Toward Efficient H2 Evolution. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Fujitsuka, M.; Yamazaki, S. Effect of Organic Additives during Hydrothermal Syntheses of Rutile TiO2 Nanorods for Photocatalytic Applications. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2019, 2, 5890–5899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odling, G.; Robertson, N. Why is Anatase a Better Photocatalyst than Rutile? The Importance of Free Hydroxyl Radicals. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 1838–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchalska, M.; Kobielusz, M.; Matuszek, A.; Pacia, M.; Wojtyła, S.; Macyk, W. On Oxygen Activation at Rutile- and Anatase-TiO2. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 7424–7431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, D.O.; Dunnill, C.W.; Buckeridge, J.; Shevlin, S.A.; Logsdail, A.J.; Woodley, S.M.; Catlow, C.R.; Powell, M.J.; Palgrave, R.G.; Parkin, I.P.; et al. Band alignment of rutile and anatase TiO2. Nat. Mater. 2013, 12, 798–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Autréaux, B.; Toledano, M. ROS as signalling molecules: Mechanisms that generate specificity in ROS homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007, 8, 813–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apel, K.; Hirt, H. Reactive Oxygen Species: Metabolism, Oxidative Stress, and Signal Transduction. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2004, 55, 373–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mittler, R. ROS Are Good. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sharma, P.A.; Jha, B.; Dubey, R.S.; Pessarakli, M. Reactive Oxygen Species, Oxidative Damage, and Antioxidative Defense Mechanism in Plants under Stressful Conditions. J. Bot. 2012, 2012, 217037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Huang, H.; Ullah, F.; Zhou, D.-X.; Yi, M.; Zhao, Y. Mechanisms of ROS Regulation of Plant Development and Stress Responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teszlák, P.; Kocsis, M.; Scarpellini, A.; Jakab, G.; Kőrösi, L. Foliar exposure of grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) to TiO2 nanoparticles under field conditions: Photosynthetic response and flavonol profile. Photosynthetica 2018, 56, 1378–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Servin, A.D.; Morales, M.I.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Hernandez-Viezcas, J.A.; Munoz, B.; Zhao, L.; Nunez, J.E.; Peralta-Videa, J.R.; Gardea-Torresdey, J.L. Synchrotron Verification of TiO2 Accumulation in Cucumber Fruit: A Possible Pathway of TiO2 Nanoparticle Transfer from Soil into the Food Chain. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 11592–11598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.; Wei, X.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Pan, D. Titanium as a Beneficial Element for Crop Production. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.F.; Wu, W.H. Potassium and phosphorus transport and signaling in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2021, 63, 34–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurusu, T.; Kuchitsu, K.; Tada, Y. Plant signaling networks involving Ca2+ and Rboh/Nox-mediated ROS production under salinity stress. Front. Plant Sci. 2015, 6, 427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Demidchik, V. ROS-activated ion channels in plants: Biophysicalcharacteristics, physiological functions and molecular nature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hedrich, R. Ion Channels in Plants. Physiol Rev. 2012, 92, 1777–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrauzer, G.N.; Strampach, N.; Hui, L.N.; Palmer, M.R.; Salehi, J. Nitrogen photoreduction on desert sans under sterile conditions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1983, 80, 3873–3876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yang, F.; Liu, C.; Gao, F.; Su, M.; Wu, X.; Zheng, L.; Hong, F.; Yang, P. The Improvement of Spinach Growth by Nano-anatase TiO2 Treatment Is Related to Nitrogen Photoreduction. Biol. Trace. Elem. Res. 2007, 119, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Xu, G.; Qian, H.; Liu, P.; Zhao, P.; Hu, Y. Effects of nano-TiO2 on photosynthetic characteristics of Ulmus elongata seedlings. Environ. Pollut. 2013, 176, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kataria, S.; Jain, M.; Rastogi, A.; Živčák, M.; Brestic, M.; Liu, S.; Tripathi, D.K. Chapter 6—Role of Nanoparticles on Photosynthesis: Avenues and Applications. In Nanomaterials in Plants, Algae and Microorganisms; Tripathi, D.K., Ahmad, P., Sharma, S., Chauhan, D.K., Dubey, N.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 2, pp. 103–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, S.S.; Tuteja, N. Reactive oxygen species and antioxidant machinery in abiotic stress tolerance in crop plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 48, 909–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanuzzaman, M.; Bhuyan, M.H.M.B.; Zulfiqar, F.; Raza, A.; Mohsin, S.M.; Mahmud, J.A.; Fujita, M.; Fotopoulos, V. Reactive Oxygen Species and Antioxidant Defense in Plants under Abiotic Stress: Revisiting the Crucial Role of a Universal Defense Regulator. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czégény, G.; Kőrösi, L.; Strid, Å.; Hideg, É. Multiple roles for Vitamin B6 in plant acclimation to UV-B. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neugart, S.; Hideg, É.; Czégény, G.; Schreiner, M.; Strid, Å. Ultraviolet-B radiation exposure lowers the antioxidant capacity in the Arabidopsis thaliana pdx1.3-1 mutant and leads to glucosinolate biosynthesis alteration in both wild type and mutant. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Colinas, M.; Fitzpatrick, T.B. Interaction between vitamin B6 metabolism, nitrogen metabolism and autoimmunity. Plant Signal. Behav. 2016, 11, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Steps | Power (W) | Ramp (min) | Hold (min) | Fan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 300 | 5 | 5 | 1 |

| 2 | 1000 | 10 | 5 | 1 |

| 3 | 1400 | 10 | 60 | 1 |

| 4 | 0 | - | 15 | 3 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kőrösi, L.; Bognár, B.; Czégény, G.; Lauciello, S. Phase-Selective Synthesis of Anatase and Rutile TiO2 Nanocrystals and Their Impacts on Grapevine Leaves: Accumulation of Mineral Nutrients and Triggering the Plant Defense. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12030483

Kőrösi L, Bognár B, Czégény G, Lauciello S. Phase-Selective Synthesis of Anatase and Rutile TiO2 Nanocrystals and Their Impacts on Grapevine Leaves: Accumulation of Mineral Nutrients and Triggering the Plant Defense. Nanomaterials. 2022; 12(3):483. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12030483

Chicago/Turabian StyleKőrösi, László, Balázs Bognár, Gyula Czégény, and Simone Lauciello. 2022. "Phase-Selective Synthesis of Anatase and Rutile TiO2 Nanocrystals and Their Impacts on Grapevine Leaves: Accumulation of Mineral Nutrients and Triggering the Plant Defense" Nanomaterials 12, no. 3: 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12030483

APA StyleKőrösi, L., Bognár, B., Czégény, G., & Lauciello, S. (2022). Phase-Selective Synthesis of Anatase and Rutile TiO2 Nanocrystals and Their Impacts on Grapevine Leaves: Accumulation of Mineral Nutrients and Triggering the Plant Defense. Nanomaterials, 12(3), 483. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12030483