Photostable and Uniform CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Film Prepared via Stoichiometric Modification and Solvent Engineering

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material Preparation

2.2. Characterizations

2.3. PL Measurement

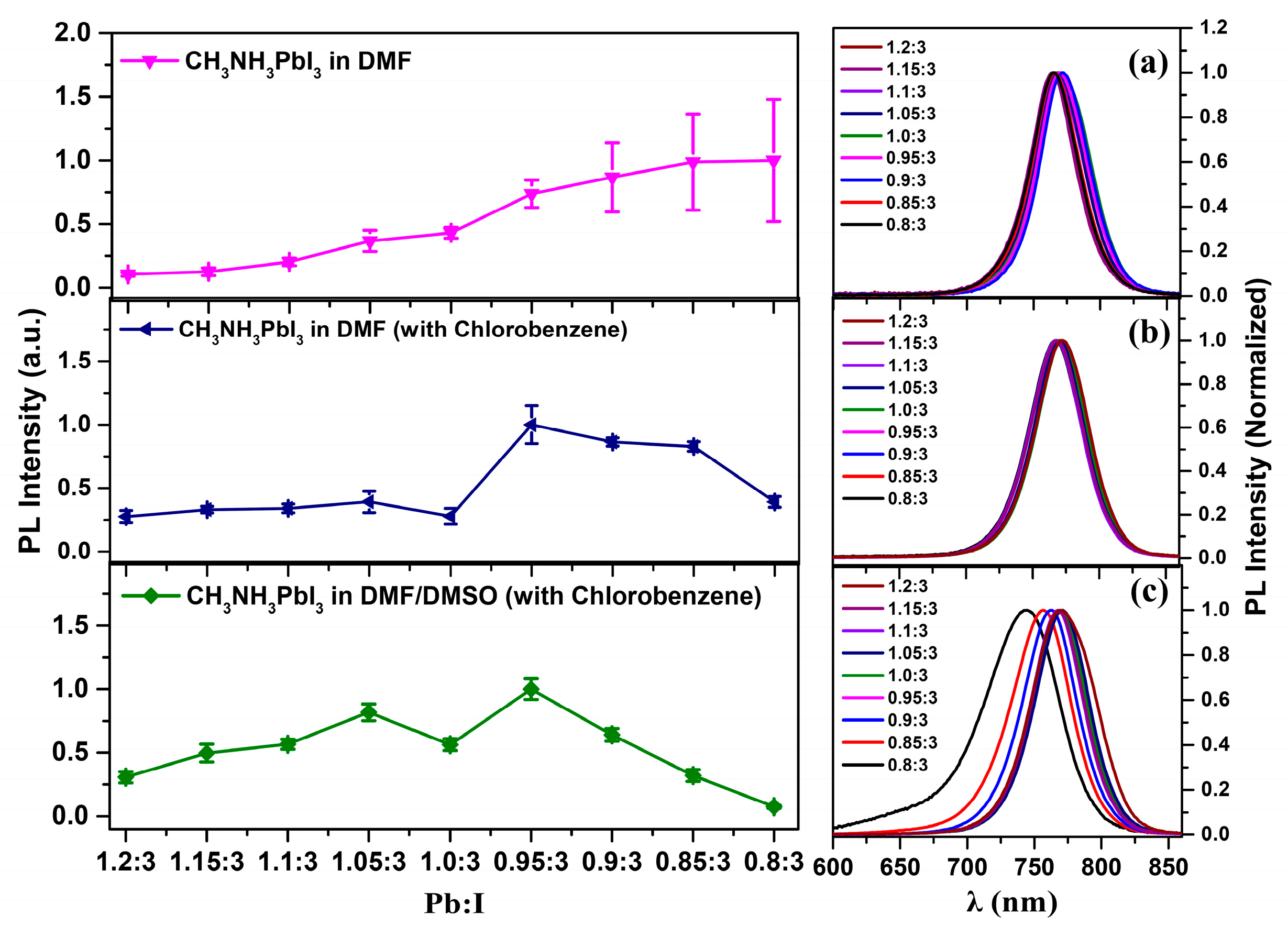

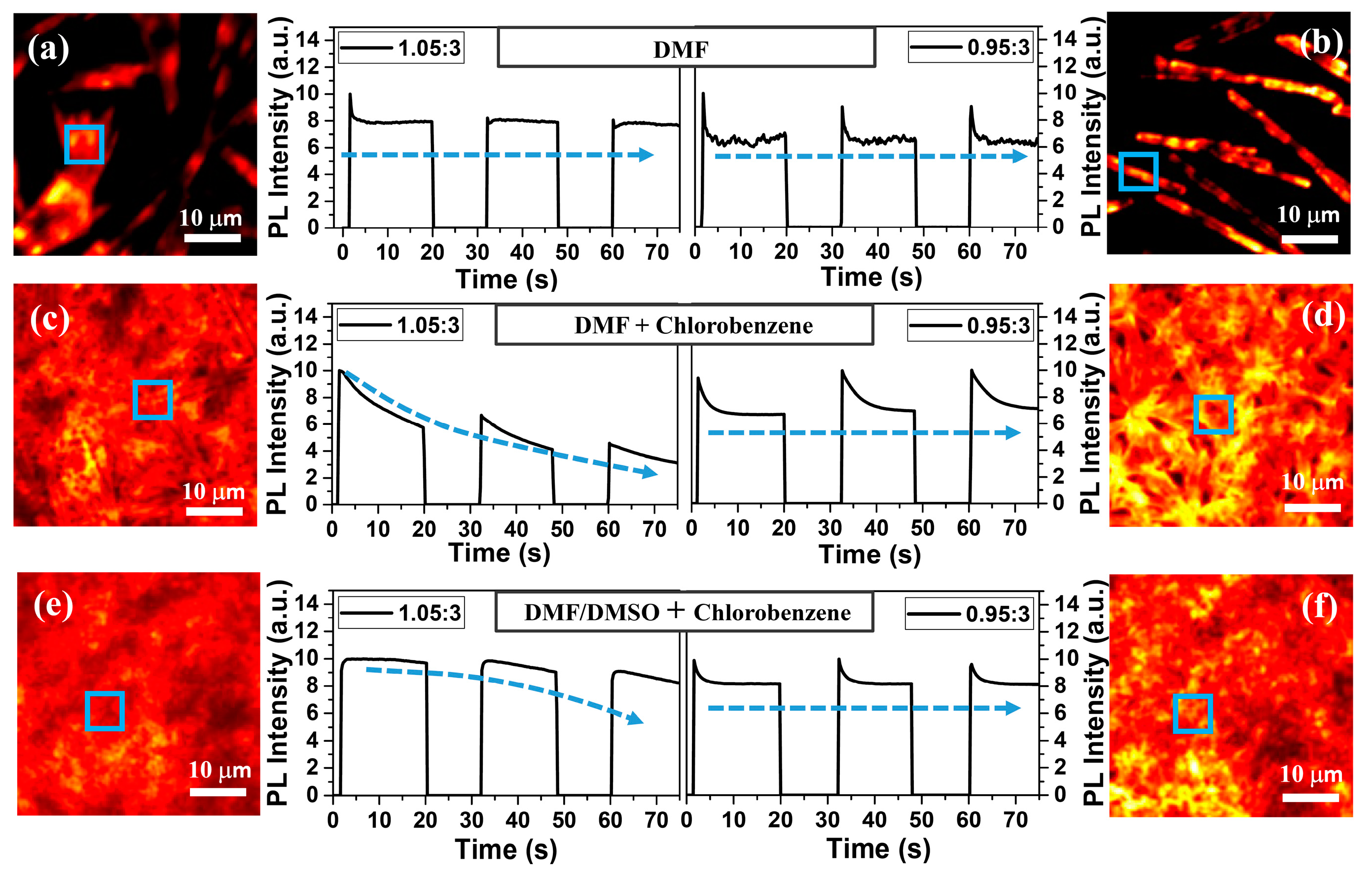

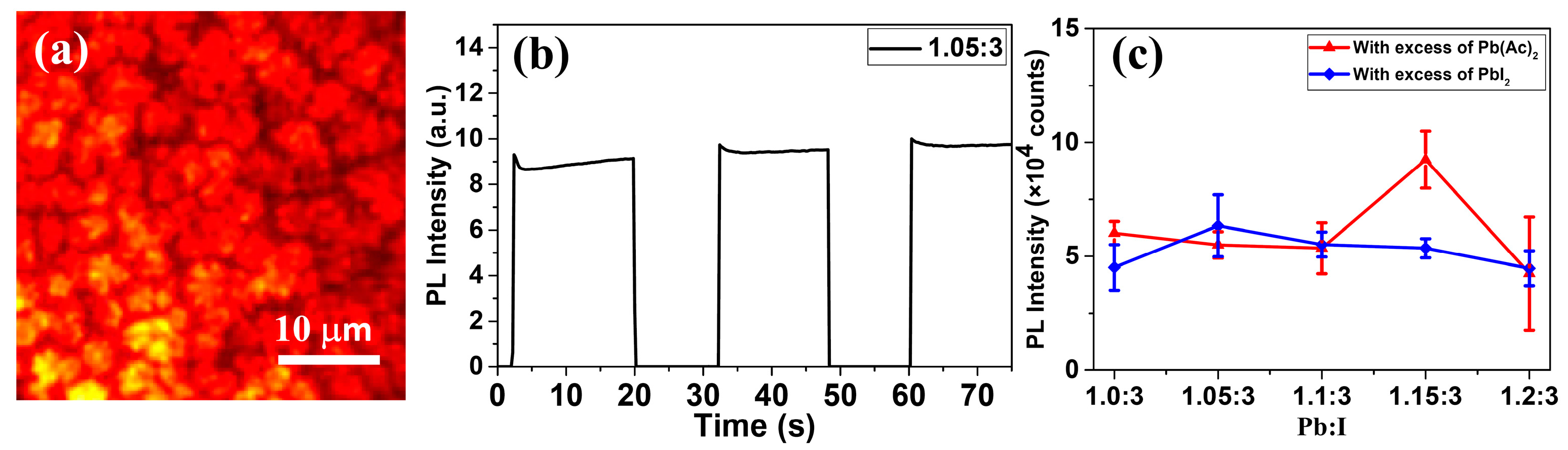

3. Results and Discussions

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Green, M.A.; Ho-Baillie, A.; Snaith, H.J. The emergence of perovskite solar cells. Nat. Photonics 2014, 8, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Z.-K.; Moghaddam, R.S.; Lai, M.L.; Docampo, P.; Higler, R.; Deschler, F.; Price, M.; Sadhanala, A.; Pazos, L.M.; Credgington, D.; et al. Bright light-emitting diodes based on organometal halide perovskite. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2014, 9, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snaith, H.J. Perovskites: The Emergence of a New Era for Low-Cost, High-Efficiency Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 3623–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, G.; Mathews, N.; Sun, S.; Lim, S.S.; Lam, Y.M.; Gratzel, M.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Sum, T.C. Long-Range Balanced Electron- and Hole-Transport Lengths in Organic-Inorganic CH3NH3PbI3. Science 2013, 342, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziang, X.; Shifeng, L.; Laixiang, Q.; Shuping, P.; Wei, W.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhijian, C.; Shufeng, W.; Honglin, D.; et al. Refractive index and extinction coefficient of CH_3NH_3PbI_3 studied by spectroscopic ellipsometry. Opt. Mater. Express 2015, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stranks, S.D.; Burlakov, V.M.; Leijtens, T.; Ball, J.M.; Goriely, A.; Snaith, H.J. Recombination Kinetics in Organic-Inorganic Perovskites: Excitons, Free Charge, and Subgap States. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2014, 2, 034007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herz, L.M. Charge-Carrier Dynamics in Organic-Inorganic Metal Halide Perovskites. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 2016, 67, 65–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponseca, C.S.; Savenije, T.J.; Abdellah, M.; Zheng, K.; Yartsev, A.; Pascher, T.; Harlang, T.; Chabera, P.; Pullerits, T.; Stepanov, A.; et al. Organometal Halide Perovskite Solar Cell Materials Rationalized: Ultrafast Charge Generation, High and Microsecond-Long Balanced Mobilities, and Slow Recombination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5189–5192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, F.; Chen, J.; Yang, S.; Xia, X.; Pullerits, T.; Deng, W.; Han, K. Ultrasensitive and Fast All-Inorganic Perovskite-Based Photodetector via Fast Carrier Diffusion. Adv. Mater. 2017, 29, 1703758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Mao, X.; Yang, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Deng, W.-Q.; Han, K.-L. Low Threshold Two-Photon-Pumped Amplified Spontaneous Emission in CH3NH3PbBr3 Microdisks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 19587–19592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyata, A.; Mitioglu, A.; Plochocka, P.; Portugall, O.; Wang, J.T.; Stranks, S.D.; Snaith, H.J.; Nicholas, R.J. Direct measurement of the exciton binding energy and effective masses for charge carriers in organic-inorganic tri-halide perovskites. Nat. Phys. 2015, 11, 582–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savenije, T.J.; Ponseca, C.S.; Kunneman, L.; Abdellah, M.; Zheng, K.; Tian, Y.; Zhu, Q.; Canton, S.E.; Scheblykin, I.G.; Pullerits, T.; et al. Thermally Activated Exciton Dissociation and Recombination Control the Carrier Dynamics in Organometal Halide Perovskite. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2189–2194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wehrenfennig, C.; Liu, M.; Snaith, H.J.; Johnston, M.B.; Herz, L.M. Homogeneous Emission Line Broadening in the Organo Lead Halide Perovskite CH 3 NH 3 PbI3−xClx. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NREL. Best Research-Cell Efficiencies: Rev. 04-06-2020; NREL: Golden, CO, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, K.; Xing, J.; Quan, L.N.; De Arquer, F.P.G.; Gong, X.; Lu, J.; Xie, L.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, D.; Yan, C.; et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes with external quantum efficiency exceeding 20 percent. Nature 2018, 562, 245–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Wang, N.; Tian, H.; Guo, J.; Wei, Y.; Chen, H.; Miao, Y.; Zou, W.; Pan, K.; He, Y.; et al. Perovskite light-emitting diodes based on spontaneously formed submicrometre-scale structures. Nature 2018, 562, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steirer, K.X.; Schulz, P.; Teeter, G.; Stevanovic, V.; Yang, M.; Zhu, K.; Berry, J.J. Defect Tolerance in Methylammonium Lead Triiodide Perovskite. ACS Energy Lett. 2016, 1, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, R.E.; Stevanović, V.; Ginley, D.S.; Buonassisi, T. Identifying defect-tolerant semiconductors with high minority-carrier lifetimes: Beyond hybrid lead halide perovskites. MRS Commun. 2015, 5, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lv, H.; Cui, C.; Xu, L.; Wang, P.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Xie, J.; Huang, J.; Tang, Z.; et al. Enhanced optoelectronic quality of perovskite films with excess CH3NH3I for high-efficiency solar cells in ambient air. Nanotechnology 2017, 28, 205401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kogo, A.; Murakami, T.N.; Chikamatsu, M. CH3NH3I Post-treatment of Organometal Halide Perovskite Crystals for Photovoltaic Performance Enhancement. Chem. Lett. 2018, 47, 1399–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueoka, N.; Oku, T.; Ohishi, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Suzuki, A. Effects of Excess PbI2 Addition to CH3NH3PbI3−xClx Perovskite Solar Cells. Chem. Lett. 2018, 47, 528–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsson, T.J.; Correa-Baena, J.-P.; Halvani Anaraki, E.; Philippe, B.; Stranks, S.D.; Bouduban, M.E.F.; Tress, W.; Schenk, K.; Teuscher, J.; Moser, J.-E.; et al. Unreacted PbI2 as a Double-Edged Sword for Enhancing the Performance of Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 10331–10343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, D.Y.; Lee, J.W.; Choi, Y.J.; Jang, I.H.; Lee, S.; Yoo, P.J.; Shin, H.; Ahn, N.; Choi, M.; Kim, D.; et al. Self-formed grain boundary healing layer for highly efficient CH3NH3PbI3perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.S.; Park, B.W.; Jung, E.H.; Jeon, N.J.; Kim, Y.C.; Lee, D.U.; Shin, S.S.; Seo, J.; Kim, E.K.; Noh, J.H.; et al. Iodide management in formamidinium-lead-halide-based perovskite layers for efficient solar cells. Science 2017, 356, 1376–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Zhou, H.; Song, T.B.; Luo, S.; Hong, Z.; Duan, H.S.; Dou, L.; Liu, Y.; Yang, Y. Controllable self-induced passivation of hybrid lead iodide perovskites toward high performance solar cells. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 4158–4163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, B.W.; Kedem, N.; Kulbak, M.; Lee, D.Y.; Yang, W.S.; Jeon, N.J.; Seo, J.; Kim, G.; Kim, K.J.; Shin, T.J.; et al. Understanding how excess lead iodide precursor improves halide perovskite solar cell performance. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, N.J.; Noh, J.H.; Kim, Y.C.; Yang, W.S.; Ryu, S.; Seok, S., II. Solvent engineering for high-performance inorganic-organic hybrid perovskite solar cells. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 897–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Islam, A.; Yang, X.; Qin, C.; Liu, J.; Zhang, K.; Peng, W.; Han, L. Retarding the crystallization of PbI 2 for highly reproducible planar-structured perovskite solar cells via sequential deposition. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 2934–2938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Tang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhong, X.; Venkatesan, S.; Graham, H.; Patton, M.; Jing, Y.; Guloy, A.M.; Yao, Y. Solvent engineering towards controlled grain growth in perovskite planar heterojunction solar cells. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 10595–10599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.W.; Yantara, N.; Boix, P.P.; Kulkarni, S.A.; Mhaisalkar, S.; Grätzel, M.; Park, N.G. High efficiency solid-state sensitized solar cell-based on submicrometer rutile TiO2 nanorod and CH3NH3PbI3 perovskite sensitizer. Nano Lett. 2013, 13, 2412–2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Xia, W.; Zhou, S.; Sun, L.; Cheng, J.; Xu, C.; Lu, Y. Solvent Engineering for Ambient-Air-Processed, Phase-Stable CsPbI3 in Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2016, 7, 3603–3608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, N.; Son, D.Y.; Jang, I.H.; Kang, S.M.; Choi, M.; Park, N.G. Highly Reproducible Perovskite Solar Cells with Average Efficiency of 18.3% and Best Efficiency of 19.7% Fabricated via Lewis Base Adduct of Lead(II) Iodide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 8696–8699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Kim, H.S.; Park, N.G. Lewis Acid-Base Adduct Approach for High Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells. Acc. Chem. Res. 2016, 49, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y.; Xiao, Z.; Bi, C.; Yuan, Y.; Huang, J. Origin and elimination of photocurrent hysteresis by fullerene passivation in CH3NH3PbI3 planar heterojunction solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 5784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Buin, A.; Ip, A.H.; Li, W.; Voznyy, O.; Comin, R.; Yuan, M.; Jeon, S.; Ning, Z.; McDowell, J.J.; et al. Perovskite–fullerene hybrid materials suppress hysteresis in planar diodes. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abate, A.; Saliba, M.; Hollman, D.J.; Stranks, S.D.; Wojciechowski, K.; Avolio, R.; Grancini, G.; Petrozza, A.; Snaith, H.J. Supramolecular halogen bond passivation of organic-inorganic halide perovskite solar cells. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 3247–3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; McCleese, C.; Kovalsky, A.; Zhao, Y.; Burda, C. Femtosecond Time-Resolved Transient Absorption Spectroscopy of CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Films: Evidence for Passivation Effect of PbI2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 12205–12208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haruyama, J.; Sodeyama, K.; Han, L.; Tateyama, Y. Termination Dependence of Tetragonal CH 3 NH 3 PbI 3 Surfaces for Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 2903–2909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buin, A.; Pietsch, P.; Xu, J.; Voznyy, O.; Ip, A.H.; Comin, R.; Sargent, E.H. Materials processing routes to trap-free halide perovskites. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 6281–6286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ham, S.; Choi, Y.J.; Lee, J.W.; Park, N.G.; Kim, D. Impact of Excess CH3NH3I on Free Carrier Dynamics in High-Performance Nonstoichiometric Perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 3143–3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Wan, S.; Tian, Y. Characterization of quenching defects in methylammonium lead triiodide (CH3NH3PbI3). J. Lumin. 2017, 192, 1191–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longo, G.; Wong, A.; Sessolo, M.; Bolink, H.J. Effect of the precursor’s stoichiometry on the optoelectronic properties of methylammonium lead bromide perovskites. J. Lumin. 2017, 30–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, Y.; Nakamura, T.; Endo, M.; Wakamiya, A.; Kanemitsu, Y. Near-band-edge optical responses of solution-processed organic–inorganic hybrid perovskite CH3NH3PbI3 on mesoporous TiO2 electrodes. Appl. Phys. Express 2014, 7, 032302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Xiao, B. Crystal Structures, Optical Properties, and Effective Mass Tensors of CH3NH3PbX3 (X = I and Br) Phases Predicted from HSE06. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2014, 5, 1278–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekimov, A.I.; Onushchenko, A.A. Quantum Size Effect in the Optical Spectra of Semiconductor Microcrystals. Sov. Phys. Semicond. 1982, 16, 775–778. [Google Scholar]

- Ekimov, A.I.; Efros, A.L.; Onushchenko, A.A. Quantum size effect in semiconductor microcrystals. Solid State Commun. 1993, 88, 947–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabpour Roghabadi, F.; Ahmadi, V.; Oniy Aghmiuni, K. Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskite Formation: In Situ Dissociation of Cation Halide and Metal Halide Complexes during Crystal Formation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 13532–13538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppel, S.; Fridman, N.; Frey, G. Amide-Templated Iodoplumbates: Extending Lead-Iodide Based Hybrid Semiconductors. Cryst. Growth Des. 2015, 15, 4363–4371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roldán-Carmona, C.; Gratia, P.; Zimmermann, I.; Grancini, G.; Gao, P.; Graetzel, M.; Nazeeruddin, M.K. High efficiency methylammonium lead triiodide perovskite solar cells: The relevance of non-stoichiometric precursors. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 3550–3556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Merdasa, A.; Unger, E.; Abdellah, M.; Zheng, K.; Mckibbin, S.; Mikkelsen, A.; Pullerits, T.; Yartsev, A.; Sundström, V.; et al. Enhanced Organo-Metal Halide Perovskite Photoluminescence from Nanosized Defect-Free Crystallites and Emitting Sites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 4171–4177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Peter, M.; Unger, E.; Abdellah, M.; Zheng, K.; Pullerits, T.; Yartsev, A.; Sundström, V.; Scheblykin, I.G. Mechanistic insights into perovskite photoluminescence enhancement: Light curing with oxygen can boost yield thousandfold. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 24978–24987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, D.; Zhou, Y.; Wan, S.; Hu, X.; Xie, D.; Tian, Y. Nature of Photoinduced Quenching Traps in Methylammonium Lead Triiodide Perovskite Revealed by Reversible Photoluminescence Decline. ACS Photonics 2018, 5, 2034–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galisteo-López, J.F.; Anaya, M.; Calvo, M.E.; Míguez, H. Environmental Effects on the Photophysics of Organic–Inorganic Halide Perovskites. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2015, 6, 2200–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, H.-H.; Adjokatse, S.; Wei, H.; Yang, J.; Blake, G.R.; Huang, J.; Even, J.; Loi, M.A. Ultrahigh sensitivity of methylammonium lead tribromide perovskite single crystals to environmental gases. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, F.; Vorpahl, S.M.; Banks, J.Q.; Sengupta, E.; Ginger, D.S. Photodecomposition and Morphology Evolution of Organometal Halide Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 20810–20816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Watthage, S.C.; Phillips, A.B.; Tompkins, B.L.; Ellingson, R.J.; Heben, M.J. Impact of Processing Temperature and Composition on the Formation of Methylammonium Lead Iodide Perovskites. Chem. Mater. 2015, 27, 4612–4619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, A.; Scanlon, D.O.; Chen, S.; Gong, X.G.; Wei, S. Self-Regulation Mechanism for Charged Point Defects in Hybrid Halide Perovskites. Angew. Chemie 2015, 127, 1811–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Khenkin, M.V.; Arnaoutakis, G.E.; Samoylova, N.A.; Barbé, J.; Lee, H.K.H.; Tsoi, W.C.; Katz, E.A. Initial Stages of Photodegradation of MAPbI3 Perovskite: Accelerated Aging with Concentrated Sunlight. Sol. RRL 2020, 4, 1900270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Bi, D.; Pellet, N.; Xiao, C.; Li, Z.; Berry, J.J.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Zhu, K.; Grätzel, M. Suppressing defects through the synergistic effect of a Lewis base and a Lewis acid for highly efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 3480–3490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakayashiki, S.; Daisuke, H.; Ogomi, Y.; Hayase, S. Interface structure between Titania and perovskite materials observed by quartz crystal microbalance system. J. Photonics Energy 2015, 5, 057410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, D.H.; Stoumpos, C.C.; Malliakas, C.D.; Katz, M.J.; Farha, O.K.; Hupp, J.T.; Kanatzidis, M.G. Remnant PbI2, an unforeseen necessity in high-efficiency hybrid perovskite-based solar cells? APL Mater. 2014, 2, 091101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calloni, A.; Abate, A.; Bussetti, G.; Berti, G.; Yivlialin, R.; Ciccacci, F.; Duò, L. Stability of Organic Cations in Solution-Processed CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskites: Formation of Modified Surface Layers. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 21329–21335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Saliba, M.; Moore, D.T.; Pathak, S.K.; Horantner, M.T.; Stergiopoulos, T.; Stranks, S.D.; Eperon, G.E.; Alexander-Webber, J.A.; Abate, A.; et al. Ultrasmooth organic-inorganic perovskite thin-film formation and crystallization for efficient planar heterojunction solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.L.; Kang, Y.S. Large-Scale Synthesis of Perpendicular Side-Faceted One-Dimensional ZnO Nanocrystals. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 4186–4190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hong, D.; Xie, M.; Tian, Y. Photostable and Uniform CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Film Prepared via Stoichiometric Modification and Solvent Engineering. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11020405

Hong D, Xie M, Tian Y. Photostable and Uniform CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Film Prepared via Stoichiometric Modification and Solvent Engineering. Nanomaterials. 2021; 11(2):405. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11020405

Chicago/Turabian StyleHong, Daocheng, Mingyi Xie, and Yuxi Tian. 2021. "Photostable and Uniform CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Film Prepared via Stoichiometric Modification and Solvent Engineering" Nanomaterials 11, no. 2: 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11020405

APA StyleHong, D., Xie, M., & Tian, Y. (2021). Photostable and Uniform CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Film Prepared via Stoichiometric Modification and Solvent Engineering. Nanomaterials, 11(2), 405. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11020405